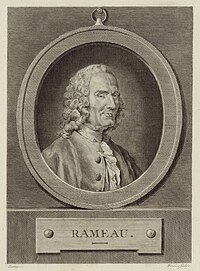

Jean Philippe Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau (25 September 1683 in Dijon - 12 September 1764 in Paris) was a French composer, harpsichordist and musical theorist who was highly influential in the Baroque era. He replaced Jean-Baptiste Lully as the dominant composer of French opera and came under heavy attack from those who preferred the style of his predecessor. He passed away in 1764, just a month before another great French musician, Jean-Marie Leclair, was assassinated.

Rameau's lyrical work—which he began to devote himself to at almost the age of 50 and consists of 31 works—constitutes the majority of his musical contribution and marks the apogee of the French Baroque. French musicologists have long opposed the use of the term "baroque" to qualify the music of Lully and Rameau (see on this subject Philippe Beaussant's book Vous avez-dit baroque?) at a time when those canons were strongly opposed to those of Italian music, until well into the 18th century. His best-known work is the opera-ballet Les Indes galantes (1735), although his are some of the masterpieces of French lyric theater, such as the tragedies Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), Castor et Pollux (1737), Dardanus (1739 and 1744) and Zoroastre (1749); the opera-ballets, Les Fêtes d'Hébé (1739) and La Princesse de Navarre (1745); or the comedy Platée (1745). His lyrical works remained forgotten for almost two centuries, but since the middle of the XX century they benefit from the general movement of rediscovery of old music.

His harpsichord works, however, have always been present in the repertoire —Le Tambourin, L'L'Entretien des Muses, Le Rappel des Oiseaux, La Poule— and were performed (on the piano) in the 19th century, in the same way as the works of Bach, Händel, Couperin or Scarlatti.

Rameau is generally regarded as the most important French musician before the 18th century and as the first theorist of harmony classical: his treatises, despite some imperfections, were until the beginning of the XX century works of reference.

Biography

« True music is the language of the heart»

(“Vraie musique est le langage du cœur”)Code de musique pratique chapitre VII article 14.

«It is to the soul that music should speak to»

(“C’est à l’âme que la musique doit parler”)Code de musique pratique chapitre XIV.

«I seek to hide art by art itself»

(“Je cherche à cacher l’art par l’art même”)Letter from Rameau to Houdar de la Motte.

Rameau's life, in general, is little known, especially his first half, the forty years that preceded his definitive settlement in Paris around 1722. He was a reserved man and even his own wife knew nothing of those years, hence the scarcity of biographical elements available.

Birth and childhood in Dijon

Seventh child in a family of eleven—five girls and six boys—Jean-Philippe was baptized in the Church of Saint-Étienne in Dijon on September 25, 1683, the same day he was born. His mother, Claudine de Martinécourt, was the daughter of a notary, a member of the gentry, and his father, Jean Rameau, the family's first musician, was an organist in the churches of Saint-Étienne and Saint-Bénigne de Dijon. Musically trained by him, Jean-Philippe learned the notes even before reading.

He studied at the Jesuit school in Godrans, although he did not stay long in the classroom: intelligent and alert, nothing interested him apart from music. His general studies got stuck and he had such disastrous results that the teachers themselves asked his father to abandon them, always suffering from poor written expression. His father wanted him to be a magistrate, but Jean-Philippe decided for himself to be a musician. His younger brother, Claude Rameau, precociously gifted for music, would also end up practicing this profession, although with much less success.

Wandering Youth

At the age of 18 his father sent him to Italy to perfect his musical education: he did not go beyond Milan and nothing is known of this short stay, since Rameau was back in France just three months later. Later he will confess to regretting not having stayed longer in Italy, where he "would have been able to perfect his taste" (& # 34; il aurait pu perfectionner son goût & # 34;).

Until he was 40 years old, his life was made up of incessant changes and little known: after his return to France he would have been part, as a violinist, of a Milanese troupe of traveling musicians —Marseille, Lyon, Nimes, Albi, Montpellier—; then he would have resided in Montpellier; in January 1702, Jean-Philippe was as interim organist in Avignon cathedral (waiting for his new head, in April, Jean Gilles); and from the following May, he was already in Clermont-Ferrand, where he obtained the position of organist of the cathedral for a period of six years.

First stay in Paris

The contract was not to be finalized, as Rameau was in Paris in 1706, as evidenced by the title page of his “Livre de pièces de clavecin”, designating him as “organiste des jésuites de Rue Saint-Jacques et des Pères de la Merci". To all appearances, at this time she was acquainted with Louis Marchand, having rented an apartment near the Chapelle des Cordeliers , in which the latter was titular organist.

Marchand had previously been—in 1703—organist at the Jesuit church on rue Saint-Jacques, a position in which Rameau was his successor. The “Livre de pièces de clavecin”, Rameau's first published work, shows the influence that this older colleague must have exerted on him. In September 1706, Jean-Philippe applied for the post of organist of the Church Sainte-Marie-Madeleine-en-la-Cité, left vacant by François d'Agincourt, who was called to Rouen Cathedral. Chosen by the jury, he finally refused the position - assigned to Louis-Antoine Dornel - because he did not want to leave his two other jobs as organist. In 1707 an aria of his, "Un duo paysan" was published in "Les Airs sérieux et à boire », in the publisher Ballard. Rameau was apparently still in Paris in July 1708. It is curious that, having served as organist for most of his career, he left hardly any pieces for this instrument.

Return to the provinces

In 1709, Rameau returned to Dijon to take charge, on March 27, of his father's succession to the organ of the cathedral. Here, too, the contract was for six years, but it was not going to be fulfilled either, since in July 1713, Rameau was in Lyon as organist of the Church of the Jacobins. He made a short stay in Dijon when his father died in December 1714 and took the opportunity to attend his brother's wedding in January 1715, returning later to Lyon.

In any case, he returned to Clermont-Ferrand and had been there at least since April, provided with a new contract at the cathedral, this time for a long term, twenty-nine years. His first biographer, Hugues Maret, tells the amusing anecdote of the way in which he managed to get out of his engagement: Rameau wanted to leave, but the Cabildo was against it; then, during a mass, the composer improvised the worst possible music, in a choppy style and using many dissonances. It was so unbearable that they asked him to stop. The Cabildo sanctioned him, but he replied that from now on he would always play like this until his freedom was granted. The Cabildo had no choice but to accept. (This same anecdote is also attributed to his brother Claude.)

He stayed there for only eight years, during which he probably composed some motets and his first cantatas, and matured the ideas that would lead to the publication in 1722 of his "Traité de l'harmonie réduite à ses principes naturels». The title page of the work describes him as "organiste de la cathédrale de Clermont". This treatise, which he had in fact been reflecting on since his youth, established Rameau as a scholarly musician. He aroused numerous echoes in the French scientific and musical circles, and even beyond its borders.

Final installation in Paris

In 1722 (or at the latest, at the beginning of 1723), Rameau was back in Paris, in conditions that are not very clear, since it is not known where he lived, and this time to stay permanently. In 1724 he published his second book of pieces for the harpsichord —“Pièces de clavecin avec une méthode pour la mécanique des doigts”— and it does not indicate the address of the composer. What is known is that his musical activity was directed towards the theatrical performances of "La Foire" ("The Fair"), festivities that were held outdoors at the Saint-Germain fairs —from February to Palm Sunday— and Saint-Laurent —from the end of July to Ascension.

I was going to collaborate with Alexis Piron —a Dijon poet established for some time in Paris, who wrote comedies and comic operas— on some works for which Rameau wrote the music, of which almost nothing remains. He did so in 1723 for L'Endriague and, in 1726, for L'Enlèvement d'Arlequin and for La Robe de dissension . When Jean-Philippe is already an established and well-known composer, he will still compose music for these popular shows, as he did in 1734 for Les Courses de Tempé ; in 1744 for Les Jardins de l'Hymen; and in 1758, already 75 years old, for Le Procureur dupé sans le savoir.

He also composed pieces for the «Comédie Italienne», especially a piece that will become famous, Les Sauvages, written on the occasion of the exhibition of authentic “savages”, North American Indians. This piece composed for harpsichord —and published in 1728 in his third harpsichord book, “Nouvelles Suites de Pièces de Clavecin”— is a rhythmic dance that will soon be taken up again in the last act of Les Gallant Indes, setting the action in a Louisiana forest. (At the La Foire fairs he also met Louis Fuzelier, who will be the librettist for the play.)

On February 25, 1726, at the Church of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois, Rameau married 19-year-old Marie-Louise Mangot at the age of 42. The wife was from a family of Lyonnaise musicians: her father, "Symphoniste du Roi", and her mother, a ballet dancer. Marie-Louise was a good musician and also a singer, and she participated in the interpretation of some of her husband's works. The couple settled in rue des Petits-Champs, they will have two sons and two daughters, and, despite the age difference and the difficult character of the musician, it seems that the couple would have had a happy life.

His first son, Claude-François, was baptized on August 8, 1727 in the same Church of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois and his brother Claude acted as godfather, with whom Jean-Philippe will maintain very good relations throughout his life. In 1727 Rameau was appointed organist of the Church of the Sainte-Croix de la Bretonnerie —he would hold this post until 1738, at least— and unsuccessfully competed for the position of organist of the Church Saint-Paul. being chosen Louis-Claude Daquin.

During those early Parisian years, Rameau continued his research and publishing activities with the publication of “Nouveau système de música théorique” (1726), a work that completed the 1722 treatise. that was the fruit of some Cartesian and mathematical reflections, in the new work the physical nature of music plays an important role. Rameau would have been aware of the works of the acoustic scholar Joseph Sauveur, works that supported and confirmed, on an experimental level, his first theoretical considerations. In the same period he composed his last cantata, Le Berger fidèle (1727), and published his third and last harpsichord book — "Nouvelles Suites de Pièces de Clavecin" (1728).

Jean-Philippe dreamed of making a name for himself in the lyric theater and was looking for a suitable librettist who would like to collaborate with him. Antoine Houdar de la Motte could have been that librettist: an established poet, he already knew success after many years of collaboration with André Campra, André Cardinal Destouches and Marin Marais. Rameau addressed him a famous letter, dated October 25, 1727, in which he tried to assert his qualities as the appropriate composer to faithfully reflect musically what the librettist expressed in his text. Houdar de la Motte, it seems, did not respond to the offer although he kept the letter, as he found it among his papers after his death.

Rameau, at 44, had a great reputation as a scholarly theorist, though he had yet to write any major musical compositions, and that at a time when he was composing young, fast, and a lot. This abstract theoretician, not very sociable, dry and blunt, without a stable job, already old and who had barely composed anything, was to become, a few years later, the official musician of the kingdom, the "dieu de la danse" (dieu de la danse) ("god of dance"), the undisputed glory of French music.

At the service of La Pouplinière

It was through Piron, apparently, that Rameau came into contact with the "fermier général" Alexandre Le Riche de la Pouplinière (1693-1762), one of the richest men from France and an "amateur" artist who maintained a circle of artists around him, of which Rameau would soon be a part. The circumstances of the meeting between Rameau and his patron are not known, although it is supposed to have taken place before La Pouplinière's exile in Provence, after a gallant affair, an exile that must have lasted from 1727 to 1731. Piron was a Dijonés like Rameau, who he had already written music for one of his plays for «La Foire». Piron was working at that time as secretary to Pierre Durey d'Harnoncourt, at the time Dijon's collector of finances and La Pouplinière's close friend and pleasure companion: he would have introduced him to Piron and he would no doubt have told him about Rameau, of his music and, above all, of his treatises that were already beginning to emerge from anonymity.

This meeting determined Rameau's life for the next twenty years and allowed him to come into contact with a very select artistic circle, where he would meet several of his future librettists, including Voltaire and his future "bête-noire" (black beast), Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the philosopher who boasted that he could teach him in music. Voltaire, at first, had a rather negative opinion of Rameau, whom he considered pedantic, extremely meticulous and boring. However, he was soon subjugated by his music and saluted his dual talents as an erudite theorist and a talented composer, and invented for him the nickname "Euclide-Orphée".

Since 1731, Rameau is supposed to have directed the private orchestra financed by La Pouplinière, an orchestra made up of high-quality musicians. He held this post—in which Stamitz and later Gossec succeeded him—for 22 years. He was also the harpsichord teacher of Thérèse Deshayes, lover of La Pouplinière from 1737 and whom he ended up marrying in 1740. Madame de la Pouplinière was from a family of artists, a fine musician herself, and of more secure taste than her husband: she was to be one of Rameau's best allies until his early separation from her in 1748, as she was, like her husband, very fickle in love matters.

In 1732, the Rameaus had a second girl, Marie-Louise, who was baptized on November 15, and by that time they were already living on rue du Chantre.

Jean-Philippe musically animated the parties given by La Pouplinière in his private palaces, first on rue Neuve des Petits-Champs, and, from 1739, on rue de Richelieu. He also encouraged other festivities organized by some of the friends of the "Fermier-general". He did so in 1733, for example, at the wedding of the financier Samuel Bernard's daughter, Bonne Félicité with Mathieu-François Molé: He played on that occasion the organ of the Church of Saint Eustace (Paris), giving him the keyboards his owner and receiving for it 1200 pounds from the rich banker, a very estimable sum for the time.

In 1733, Rameau was already 50 years old. A famous theoretician for his treatises on harmony, he was also a musician of appreciable talent as an interpreter, both on the organ, harpsichord and violin, and also in front of the orchestra. However, his work as a composer was limited to several motets and cantatas and three recueils (selections) of harpsichord pieces, of which only the last two stood out for their innovative aspect. By this time his contemporaries of the same age—such as Vivaldi (five years older), Telemann (two years older), Bach, and Handel (both two years younger)—had already composed the gist of a very important work. Rameau presents a very particular case in the history of baroque music: this fiftieth-year-old "debutant composer" ("compositeur débutant") possessed a thorough trade that had not yet manifested itself in his favorite field, the lyrical scene, where he would eclipse soon to all his contemporaries.

Success: Hippolyte et Aricie

Abbot Simon-Joseph Pellegrin —a religious suspended a divinis by the Archbishop of Paris for being heavily invested in the world of theater— had already been writing opera or opera-ballet librettos since 1714. He frequented the house of La Pouplinière and there he met Rameau and provided him with the libretto for a «tragédie en musique», Hippolyte et Aricie, which suddenly placed the composer in the firmament of the scene French lyric. With this libretto, in which the action was freely inspired by Jean Racine's Phèdre —and further back, in the tragedies of Seneca and Euripides— Rameau captured in a work his reflections of almost a lifetime, because he was able to put music to all theatrical situations, passions and human feelings, as he had tried in vain to make Houdar de la Motte assert. Surely in Hippolyte et Aricie he also submitted to the particular demands of musical tragedy, a genre that gives an important place to choirs, dances and special machine effects. Paradoxically, the piece associates very erudite and modern music with a well-known form of lyrical performance, which had had great hours at the end of the previous century, but which at that time was considered outdated.

The piece was staged privately at La Pouplinière's house in the spring of 1733. Rehearsals were held at the Académie Royale de Musique beginning in July, with the first performance taking place on October 1. The play puzzled everyone at first, but was ultimately a triumph. Following the Lully tradition in terms of structure—a prologue and five acts—it surpassed musically anything that had gone before in the field. The old composer André Campra, who attended the performance, estimated that there was “(...) enough music in this opera to make ten”, adding that “this man will outshine them all ». Even so, Rameau had to rework the initial version, since the singers failed to interpret correctly some of his arias, especially the "Second trio des Parques" in which the rhythmic and harmonic audacity was incredible for the time.

The work did not leave anyone indifferent: Rameau was praised at the same time by those who loved the beauty, science and originality of his music and criticized by those nostalgic for the style of Lully, who disliked the audacity and they proclaimed that true French music was being devalued for the benefit of a bad Italianism. The opposition on both sides was all the more surprising since Rameau professed to Lully, throughout his life, unconditional respect, which is certainly not surprising. The dispute is known as the "Querelle entre les Lullistes et les Ramistes" (or "Querelle entre les Anciens et les Modernes"). With 32 performances in 1733, Hippolyte et Aricie consecrated Rameau definitively and placed him at the forefront of French music. The piece will be revived three more times during the composer's lifetime at the Académie Royale de Musique and, already the following year, in 1734, it was staged in his hometown, Dijon.

First lyrical career (1733-1739)

During the seven years between 1733 and 1739, Rameau gave the measure of his genius and seemed to want to make up for lost time by composing his most emblematic works: three lyrical tragedies —after Hippolyte et Aricie, Castor et Pollux in 1737 and then Dardanus in 1739— and two opera-ballets —Les Indes galantes in 1735 and Les Fêtes d& #39;Hébé in 1739—. This did not prevent him from continuing his theoretical work: in 1737 he published his treatise on the "Génération harmonique" , in which he took up and developed the preceding treatises. The exhibition, intended for members of the Académie des Sciences, began with the statement of twelve propositions and the description of seven experiments with which Rameau understood that his theory was proven by law, since it came directly from nature, a theme much loved by the intellectuals of the «Age of Enlightenment».

As early as 1733, Rameau and Voltaire considered collaborating on a sacred opera entitled Samson. The previous year, Abbot Pellegrin had known his greatest success with Jephté, set to music by Montéclair, thus opening what seemed like a new path. Voltaire strove to compose his script, although the religious vein was not really his thing. Setbacks came with his exile in 1734; Rameau himself, enthusiastic at first, gave up waiting and did not seem very motivated, and only a few partial rehearsals were held. The mixture of genres, between the Biblical recitation and the opera of gallant intrigues, was not to everyone's taste and particularly the religious authorities. In 1736, the censorship prohibited the work, which would never be finished or, above all, represented. The libretto was not lost and was edited by Voltaire some years later. It is known that the music that Rameau had composed was used by him in other works, although it is not yet known in which or in which parts.

It didn't matter, as the year before, 1735, saw the birth of his first masterpiece, the opera-ballet Les Indes galantes, probably Rameau's best-known stage work and one of peaks of the genre, which takes place on a libretto by Louis Fuzelier. The first attempt in the field of musical tragedy was a complete success: it is of the same type, lighter, of the opera-ballet perfected by André Campra in 1697 with Le Carnaval de Venise and on all L'Europe gallant. The similarity of titles left no room for surprise: Rameau exploited the same vein of success but looking for a little more exoticism, with his "Indies", geographically imprecise, since in fact they were from Turkey, Persia, Peru and South America. North. The almost non-existent intrigue of these little dramas served as an excuse to produce a "grand spectacle" in which sumptuous costumes, decorations, machinery and above all dance played an essential role. Les Indes galantes symbolizes the carefree, refined era, dedicated to the pleasures and gallantry of Louis XV and his court. The work was premiered at the Académie Royale de Musique on August 23, 1735, with great success and consisted of a prologue and two "entrées". For the third performance, the "Entrée des Fleurs" was added and then the play was quickly retouched after criticism concerning the libretto—in which the intrigue is particularly far-fetched. The fourth "entrée", Les Sauvages, was finally added on March 10, 1736 and Rameau reused in it "La danse des Indiens d'Amérique", a piece he had composed several years earlier. and later transcribed for harpsichord in his third book. Les Indes galantes was revived, in whole or in part, five times during the composer's lifetime and a few more after his death.

At this time, already famous, the Rameaus moved to the Hôtel d'Effiat, at 21 rue des Bons Enfans (near the Palais Royal) where in 1738 Jean-Philippe opened a private class in composition. They will live here for almost nine years, until 1744, when they move to rue Saint Thomas du Louvre, in one of the longest stays of their lives.

On October 24, 1737, his second lyric tragedy, Castor et Pollux, premiered with a libretto by Gentil-Bernard, whom he had also met at La Pouplinière's house. By almost general consensus, the libretto that narrates the adventures of the divine twins who love the same woman, is one of the best that the composer has tried (even if Gentil-Bernard's talent does not deserve Voltaire's dithyrambic appreciation).. The work benefits from an admirable music although less audacious than that of Hippolyte et Aricie —Rameau never wrote arias comparable, in audacity, to the second "Trio des Parques" or to Theseus' aria "Puissant maître des flots»—and ends with a diversion, the «Fête de l'Univers», after the heroes are accommodated in the room of the Immortals.

In 1739, one after another, Les Fêtes d'Hébé —the second opera-ballet, with a libretto by Antoine-César Gautier de Montdorge— was premiered on May 25 and on November, Dardanus —third lyrical tragedy, with a libretto by Charles-Antoine Leclerc de La Bruère—. If Rameau's music is always very sumptuous, the libretti become poorer and poorer and must be quickly touched up in order to hide the most glaring defects.

Les Fêtes d'Hébé was an immediate success, but still Abbot Pellegrin was called upon to improve the libretto (particularly the second entrée) after a few performances. The third “entrée” (“La Danse”) was especially appreciated, with its fascinating pastoral character —Rameau reused in it, orchestrating it, the famous Tambourin from his second harpsichord book— which contrasts with a one of the most admirable "musettes" that he has composed, and which, in turn, is played, sung and performed in chorus.

As for Dardanus, musically perhaps the richest of Rameau's works, it was initially poorly received by the public, probably due to the insubstantiality of the libretto and the innocence of certain scenes. Modified after a few performances, the opera was almost entirely rewritten in its last three acts for a revival in 1744: in fact it is almost a different work.

Seven years of silence

After a few years of composing one masterpiece after another, Rameau mysteriously disappeared for six years from the lyrical scene, and almost from the musical scene, since he did not premiere anything except in 1744 that new version of Dardanus.

The reason for this sudden silence is not known, although it could be due to a disagreement with the authorities of the Académie Royale de Musique. Rameau probably devoted himself to his position as conductor of La Pouplinière, for by this time he had doubtless already left all his posts as organist (the last, in 1738, that of the church of Sainte-Croix de la Bretonnerie). He did not write any other theoretical writing either and it seems that he only composed in those years the Pièces de clavecin en concert, probably born from concerts organized at the home of the "Fermier-général" and which is Rameau's only foray into in the field of chamber music.

In 1740 their third son, Alexandre, was born, and the godfather was La Pouplinière. The child died before 1745. The last daughter, Marie-Alexandrine, was born in 1744. From that same year, Rameau and his family will have an apartment in the Palace of the "Fermier-général", on rue de Richelieu: they arranged from him for twelve years, although they probably kept their own apartment on rue saint-Honoré. They will also spend every summer in the castle of Passy acquired by La Pouplinière, where Rameau will take charge of the organ.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau arrived in Paris in 1741 and was brought into the house of La Pouplinière, in 1744 or 1745, through a cousin of Madame de la Pouplinière. Although an admirer of Rameau, he was received without sympathy and with a certain contempt for him, since he was persecuting the mistress of the house, then the composer's best support. Rousseau was very proud of the invention of a cipher system for annotating music, much simpler, according to him, than the traditional system of the "portée." Rameau was quick to refute him, for practical reasons that the inventor was forced to admit. Having attended the performance of an opera, Les Muses galantes, of which Rousseau claimed to be the author, at the house of the "Fermier-général", Rameau accused him of plagiarism, having discovered from different parts of the work inequalities of musical quality that he supposed were due to different hands. Animosity was born between them from this first contact and only grew in the years to come.

Second lyrical career

Rameau reappeared on the lyric scene in 1745 and that same year, at the age of over 60, he was to almost monopolize the season with the premiere of five new works that speak of his vitality: on February 23, La Princesse de Navarre —ballet-comedy with a libretto by Voltaire, performed in Versailles on the occasion of the wedding of Louis, Dauphin of France—; on March 31, Platée —lyrical comedy of an unprecedented style, premiered at Versailles, which in the comic register was Rameau's masterpiece—; on October 12, Les Fêtes de Polymnie —opera-ballet—; on November 27, Le Temple de la Gloire —ballet-opera, again with a libretto by Voltaire, performed in Versailles to celebrate the victory of Fontenoy (Austrian succession wars), which will be almost remade the next year-; and finally, on December 22, Les Fêtes de Ramire —a ballet act performed in Versailles—. Rameau became the official musician of the Court: he was appointed "Compositeur de la Musique du Cabinet du Roi" in May, and will receive an annual pension of 2,000 pounds from then on.

Les Fêtes de Ramire was a piece of pure entertainment in which the music had to reuse part of the music composed for La Princesse de Navarre, with a minimal libretto written by Voltaire. As Rameau was busy with the Temple de la Gloire , Jean-Jacques Rousseau, just a good musician despite his pretensions, was put in charge of the musical adaptation, but he did not finish the job at all. time. Rameau, possibly nervous, was then forced to do it himself, at the price of Rousseau's humiliation. This new incident further degraded relations that were already very sour at that time.

After the «feu d'artifice» of 1745, the pace of the composer's production then slowed down, although Rameau would continue composing for the stage, more or less regularly, until the end of his life, and this without abandoning his theoretical investigations or, either, his polemical and pamphleteering activities. Thus, he composed in 1747 Les Fêtes de l'Hymen et de l'Amour and his last work for the harpsichord, an isolated piece entitled La Dauphine; in 1748, the pastoral Zaïs, the ballet act Pygmalion and the opera-ballet Les Surprises de l'Amour; in 1749, the pastoral Naïs (to celebrate the "Paix d & # 39; Aix-la-Chapelle") and the lyrical tragedy Zoroastre , an innovative piece in which he suppressed the prologue, replaced by a simple overture; in 1751, finally, he composed the ballet act La Guirlande and the pastoral Acanthe et Céphise (to celebrate the birth of the Duke of Burgundy).

It was probably during this period that Rameau came into contact with Jean d'Alembert, who was interested in a scientific approach to the composer's music and who encouraged Rameau to present the results of his work to the Academy of Sciences. In 1750, perhaps aided by Diderot, he published his treatise entitled "Démonstration du principe de l'harmonie", a work that is generally considered the best of all the theoretical works of he. D'Alembert made the presentation - the praise - of Rameau and wrote in 1752 the «Éléments de musique théorique et pratique selon les principes de M. Rameau». Later he will retouch in his favor some of the articles of the "Encyclopédie" written by Rousseau. But his paths diverged a few years later when the philosopher-mathematician became aware of the errors in Rameau's thought concerning the relationship between pure sciences and experimental sciences. At that time, Rameau sought the approval of his work by the greatest mathematicians of the day, which led him to exchange letters with Jean Bernoulli and Léonard Euler.

In 1748, La Pouplinière and his wife separated and Rameau lost his most faithful ally in the house of his patron. He was approaching 70 years of age, his activity was still prodigious and this left little room for competition, which exasperated more than one and certainly played a role in the attacks he suffered during the famous "Querelle des Bouffons". But age did not give him more flexibility and he remained attached to his ideas.

The “Querelle des Bouffons”

To understand the significance of the «Querelle des Bouffons», it is necessary to remember that around 1750 France was, musically speaking, very isolated from the rest of Europe, which had long supported the supremacy of Italian music. In Germany, Austria, England, the Netherlands, the Iberian Peninsula, Italian music had swept away or at least assimilated with local traditions. Only France could still figure as a stronghold resistant to this hegemony. The symbol of this resistance was the musical tragedy of Lully—at that time symbolized by the old Rameau—and yet the attraction of Italian music had long been felt in the practice of instrumental music. The antagonism born between Rameau and Rousseau —a personal enmity aggravated by two totally opposite conceptions in musical matters— also personalized this confrontation, which will give rise to a true verbal, epistolary, almost physical debauchery between the «Rincón del Rey» («Coin du Roi"), supporters of the French tradition, and the "Rincón de la Reina" ("Coin de la Reine"), supporters of Italian music.

Since the beginning of 1752, Frédéric-Melchior Grimm, a German journalist and critic living in Paris, had battered the French genre in his Lettre sur Omphale —published after the revival of this lyrical tragedy composed at the turn of the century by Destouches—proclaiming the superiority of Italian dramatic music. Rameau was not taken for granted by this pamphlet, as Grimm at the time held a high opinion of Rameau as a musician.

On August 1, 1752, an itinerant Italian troupe set up shop at the Académie Royale de Musique to give performances of intermezzos and comic operas. They made their debut with the representation of La serva padrona by Pergolesi, a work that had already been offered in Paris in 1746, without attracting the slightest attention. This time it was a success. The intrusion into the temple of French music by these "bouffons" divided the Parisian musical intelligence into two camps: on the one hand, supporters of lyrical tragedy, the true representative of the French genre, and on the other, sympathizers of opera. -bufa, truculent defenders of Italian music. A real pamphleteering dispute arose between both sides that would animate the musical, literary and philosophical circles of the French capital until 1754.

In fact, the «Querelle des Bouffons», unleashed under a musical pretext, was, basically, the confrontation of two aesthetic, cultural and, in the end, political ideas, definitely incompatible: on the one hand, classicism, associated to the image of the absolute power of Louis XIV; on the other, the spirit of the Lights. Rameau's highly refined music found itself put "dans le même sac" than the theatrical pieces that served as a mold and plot for him, with their accoutrements of mythology, wonders, and machines, to which philosophers wanted to oppose simplicity, the natural and the spontaneity of the Italian opera-buffa, characterized by a music that gave primacy to the melody.

And precisely everything that Rameau had written for thirty years defined harmony as the principle, the very nature of music. Thus it was difficult to reconcile the learned musician, sure of his ideas, proud, stubborn and quarrelsome with Rousseau, an "amateur" musician, whom Rameau despised from the beginning, since he had allowed himself to contradict his theories. The vindication of him also reached the "Encyclopédie", since it was Rousseau who Diderot commissioned to write the articles on music.

The "Queen's Corner" grouped the encyclopedists, with Rousseau, Grimm, Diderot, d'Holbach and, later, d'Alembert; Criticism focuses on Rameau, the main representative of the "Rincón del Rey". They exchanged a considerable number of libels, articles —more than sixty—, the most virulent coming from Grimm («Le petit prophète de Boehmischbroda») and from Rousseau («Lettre sur la musique française » where it is stated that only the recitative is suitable for the French language and it is impossible for another kind of music). Rameau is not sitting still ("Observation sur notre instinct pour la musique") and will continue to throw his darts long after the "Querelle" has died down: "Les erreurs sur la musique dans l'Encyclopédie" (1755), "Suite des erreurs" (1756), "Réponse à MM. les éditeurs de l'Encyclopédie" (1757). There was even a duel in 1753 between Ballot de Sauvot, librettist —Pygmalion, 1748— and admirer of the composer, and the Italian castrato Gaetano Caffarelli, who was injured. The "Querelle" ended up being extinguished, but lyrical tragedy and related forms had received such blows that his time was over.

Only Rameau, who will retain all his prestige as official composer of the court until the end of his life, will henceforth be allowed to write in that genre, since then considered outdated. And his inspiration did not run out: in 1753, he composed the heroic pastoral Daphnis et Églé, a new lyrical tragedy, Linus, the pastoral Lysis et Délie —these last two compositions were not performed and their music was lost—, as well as the ballet act Les Sybarites. In 1754 he still composed two ballet acts: La Naissance d'Osiris (to celebrate the birth of the future Louis XVI) and Anacréon, as well as a new version of < i>Castor et Pollux.

Last years

In 1753, La Pouplinière took as his lover an intriguing musician, Jeanne-Thérèse Goermans —daughter of the well-known harpsichord maker Jacques Goermans—, who called herself Madame de Saint-Aubin because she was married to a profiteer who left her in his arms of the rich financier She made a vacuum around Rameau and even got La Pouplinière to hire Stamitz: it was the break with Rameau who, by the way, will no longer need the financial support of his former friend and protector.

Rameau continued his activities as a theoretician and composer until his death. He lived with his wife and two of their children in a large apartment on rue des Bons-Enfants, from where he left every day, lost in thought, to take his solitary walk through the nearby gardens of the Palais-Royal or the Tuileries.. He sometimes met the young Chabanon who will later write his funeral eulogy and who has collected some of his rare secrets, already then very disappointed:

"Day I acquire more taste, but I have no more genius" or "The imagination is worn on my old head, and it is not wise when you want to work at this age in the arts that are entirely imagination". "De jour en jour j'acquiers du goût, mais je n'ai plus de génie...» or «L'imagination est usée dans ma vieille tête, et on n'est pas sage quand on veut travailler à cet âge aux arts qui sont entièrement d'imagination...»).Rameau.

His pieces continued to be represented, sometimes out of deference to the old composer, who in 1757 closed an exclusive contract with the Académie Royale de Musique —directed by Rebel and Francœur— which guaranteed him an annual pension of 1,500 pounds. In 1756 he programmed a second version of Zoroastre . In 1757, Anacréon is performed, a new “entrée” added to Les Surprises de l'Amour. In 1759, Dardanus was revived with great success and, in 1760, Les Paladins premiered, a comedy-ballet in a renewed style that served, however, to continue settling scores., in writing, with the "Encyclopédie" and the philosophers. In 1761 Rameau is named a member of the Académie de Dijon.

His last writings, especially “L'Origine des sciences”, were marked by his obsession with making harmony the reference point of all science, which led to Grimm's opinion that he spoke of the dotage ("radotage") of the "vieux bonhomme". But Rameau still kept all his lucidity and, at the age of more than 80 years, composed his last tragedy in music, Les Boréades , a work of great novelty but of a novelty that does not go in the direction it is taking. then the music. In the spring of 1764 Rameau was made "chevalier de l'Ordre de Saint-Michel" and began rehearsals for Boréades, but the play, for reasons unknown, will not be performed. Rameau died of a "putrid fever" on September 12, 1764 and Les Boréades had to wait more than two centuries for its triumphant premiere in Aix-en-Provence in 1982.

The following day, September 13, the great musician was buried in the Church of Saint-Eustache in Paris. Various tribute ceremonies took place in the following days in Paris, Orléans, Marseille, Dijon and Rouen. The funeral eulogies, written by Chabanon and Maret, were published by the "Mercure de France". His stage music, like Lully's, continued to be programmed until the end of the Old Regime, and then disappeared from the repertoire for more than a century.

Rameau's personality

"Your daughter and his wife can die whenever they want; whenever the bells of the parish, which they will stumble for them, they will continue to touch the twelfth and the seventeenth, everything will be fine." (...) "Then tell me; I would not take your uncle for example; he is a tough, brutal, inhuman, greedy man. He is a bad father, a bad husband, a bad uncle...».Diderot en Le Neveu de Rameau(The nephew of Rameau)

Just as his biography is imprecise and partial, Rameau's personal and family life is almost completely opaque and everything disappears behind his musical and theoretical work. Even his music, sometimes so graceful and light, is in character opposite to the outward appearance of the man and to what is known of his character, described in a caricatural and perhaps exaggerated way by Diderot in Le neveu de Rameau. Throughout his life, Rameau was only interested in music, with passion and occupied all his thoughts. Philippe Beaussant speaks of a monomaniac. It was Piron who explained that: «All his soul and his spirit were in his harpsichord; when he had closed it, there was no other person in the room ».

Physically, Rameau was large and above all very thin: the notes we have of him —especially one by Carmontelle, which shows him in front of his harpsichord— describe him as a kind of rod or stud with endless legs. He had "une grosse voix" and his speech was difficult, like his written expression, which was never fluent.

He was at once secretive, lonely, grumpy, smug (prouder, by the way, as a theoretician than as a musician) and married to his contradictions, he let go easily. It is hard to imagine him surrounded by the high spirits—like that of Voltaire, to whom he bore a certain physical resemblance—who frequented the La Pouplinière residence: his music was his best ambassador in the absence of more mundane qualities.

Her "enemies"—those who didn't share her views on music or acoustic theory—amplified her shortcomings, such as her alleged greed. In fact, it seems that his care of the economy was the consequence of a long dark career, with minimal and uncertain income, rather than a trait of his character, since he could be generous: it is known that he helped his nephew Jean-François to reach to Paris and his young Dijon colleague Claude Balbastre likewise to settle in Paris; that he endowed her daughter Marie-Louise well in 1750 when she took the habit at the Visitandines; and that he punctually paid a pension to one of his sisters who was ill.

Financial relief came late, with the success of his lyrical works and the attribution of a pension by the king (a few months before his death, he was even ennobled and made a knight of the Order of Saint Michael). But it did not change his way of life, keeping his worn-out clothes, his only pair of shoes, or his dilapidated furniture. At his death, in the ten-room apartment he occupied on rue des Bons-Enfants with his wife and son, he had at his disposal only a single-keyboard harpsichord, and in poor condition. He found among his belongings a sack containing 1,691 louis d'or.

A character trait that is certainly found in other members of his family was a certain inconstancy: he settled in Paris around the age of 40, after an erratic phase and having held many organist positions in different cities: Avignon, maybe Montpellier, Clermont-Ferrand, Paris, Dijon, Lyon, Clermont-Ferrand again and finally Paris. Even in the capital, he often changed his address: rue des Petits-Champs (1726), rue des Deux-Boules (1727), rue de Richelieu (1731), rue du Chantre (1732), rue des Bons-Enfants (1733), rue Saint-Thomas du Louvre (1744), rue Saint-Honoré (1745), rue de Richelieu at La Pouplinière's (1746), and again rue des Bons-Enfants (1752). The cause of these successive changes is not known.

Her family

Rameau had four children with his wife Marie-Louise Mangot:

- Claude, born in 1727. His father bought him a royal chamber valet; he married in 1772 and had a son in 1773.

- Marie-Louise, born in 1732, who took the habits with the Visitandines in Montargis in 1751 (the father gave it generously but did not attend the ceremony).

- Alexandre, born in 1740 and dead before 1745.

- Marie-Alexandrine, born in 1744 (Rameau was then 61 years old). He was married in 1764, two months after the death of his father, with François de Gaultier, of whom he was descended.

After Rameau's death, his wife left the apartment on rue des Bons-Enfants in Paris and went to live with her son-in-law in Andrésy, a small town in the Yvelines. She died there in 1785.

The names of the last two children were a tribute to the "Fermier-général" Alexandre de la Pouplinière, Rameau's patron thanks to whom he was able to begin his career as a lyric composer.

Jean-Philippe had a younger brother, Claude, also a (much less famous) musician. The latter had two sons, musicians like him but with an existence of "ratés" (failures): Jean-François Rameau who inspired Diderot the material of his book Le Neveu de Rameau ("The nephew of Rameau») and Lazare Rameau.

The art of Rameau

"When he composed, he was numb" (Quand il composait, il était dans l'enthousiasme)Hugues Maret. Cited by Jean Malignon, p. 85.

Rameau's music is characterized by the exceptional skill of this composer who wants to be above all a theoretician of his art. It is not addressed only to intelligence and Rameau was able to ideally put his intention into action when he stated "Je cherche à cacher l'art par l'art même" (I seek to hide art by art itself).

The paradox of this music, what is new about it, is the implementation of previously non-existent procedures, but which materialize in obsolete forms. Rameau seemed revolutionary to the lullystas, defeated by the complex harmony that he displayed, and reactionary to the philosophers, who only judged his continent and could not, or did not want to, listen to him. The misunderstanding he suffered from his contemporaries prevented him from resuming some licenses —such as the second “trio des Parques” from Hippolyte et Aricie, which he had to withdraw after the first performances—, since the singers they could not interpret it correctly. Thus, the greatest harmonist of his time is ignored even then, when harmony—the "vertical" aspect of music—definitively takes advantage over counterpoint, which represents its "horizontal" aspect.

You cannot compare the fates of Rameau and Bach, the two giants of musical science of the 18th century, rather than as isolated from all their colleagues, when everything else separates them. In this regard, the year 1722 - which saw the simultaneous appearance of the «Traité de l'Harmonie» and the first cycle of Das wohltemperierte Klavier (The Clavier well-tempered)- is very symbolic. French musicians at the end of the XIX century were not mistaken, in the midst of Germanic musical hegemony, when they saw Rameau as the only French musician of strength comparable to Bach, which allowed the progressive rediscovery of his work.

Musical work

Rameau's musical output comprises four distinct ensembles of highly unequal importance: the cantatas; the motets for large choir; the harpsichord pieces, soloist or in concert; and lyrical music, to which he devoted almost exclusively the last thirty years of his career.

Like most of his contemporaries, he often reused arias, particularly well done or appreciated, but never without meticulously adapting them: they were never mere transcriptions. These transfers are many: it is found in Les Fêtes d'Hébé, L'Entretien des Muses, the "Musette" and the "Tambourin" taken from the < i>Harpsichord book from 1724 and an aria taken from Berger's cantata Fidèle; or, also, another Tambourin passed successively from Castor et Pollux to the Pièces en concert, and, later, from the second version of Dardanus; other examples abound.On the other hand, imitations of other musicians were not found in his work, all the more influences from the beginning of his career.

Motets

Rameau was for more than forty years a professional organist at the service of various religious institutions, parishes or convents, but even so his production in terms of sacred music is very limited, and this is without mentioning the organ work that, in its case, it has not been preserved.

Evidently it was not his preferred land, but, at best, a means of earning an appreciable livelihood. His rare religious compositions are, however, remarkable and compare favorably with those of specialists in the genre.

The works that can be attributed to him with certainty, or almost, are only the following four:

- Deus noster refugium (age 1713-1715);

- Quam diletta (age 1713-1715);

- In convert (without doubt prior to 1720);

- Laboravi (in the Traité de l'harmonie1722.

Other motets are of doubtful attribution, such as Diligam te and Inclina Domine.

Cantatas

At the beginning of the 18th century, the cantata was a highly successful genre: the French cantata — as distinguished from the Italian or Germanic cantata - was "invented" in 1706 by the poet Jean-Baptiste Rousseau and soon adapted by various renowned musicians such as Bernier, Montéclair, Campra or Clérambault.

The cantatas were for Rameau the first contact with lyrical music, since they need only reduced means and, therefore, they are an accessible genre for still unknown musicians. Musicologists have only been able to guess the dates and circumstances of its composition, and its librettists remain unknown.

The surviving cantatas attributed with certainty to Rameau are only the following six (data are estimates):

- Aquilon et Orithie (between 1715 and 1720);

- Thétis (same period);

- L'Impatience (same period);

- Les amants trahis (about 1720)

- Orphée (same period);

- Le Berger Fidèle (1728).

Maret, in his eulogy read in solemn session on August 25, 1765 before the «Académie des Sciences, Arts et Belles-Lettres» of Dijon (in fact, the first biography), evokes two more cantatas composed in Clermont-Ferrand and today lost: Médée and L'Absence. He is also credited with another, the Cantate pour le jour de la saint-Louis .

Instrumental music

Rameau is, along with Couperin, one of the two great masters of the French harpsichord school in the 18th century. The two musicians clearly differ from the first generation of harpsichordists who poured their compositions into the relatively fixed mold of the classical suite. This reached its height during the decade 1700-1710 with the successive appearances of suite books by Louis Marchand, Gaspard Le Roux, Louis-Nicolas Clérambault, Jean-François Dandrieu, Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, Charles Dieupart and Nicolas Siret.

But both practiced a very different genre, and in no case can Rameau be considered the heir to their elder. They seem to ignore each other. Couperin was one of the official musicians of the Court while Rameau was still only unknown: glory would come to him the same year as Couperin's death. By the way, Rameau published his first books from 1706 while François Couperin, who was fifteen years older, waited until 1713 to have his first orders published. Rameau's pieces seem less designed for the harpsichord than Couperin's and attach less importance to ornamentation. Taking into consideration the respective volume of his contributions, Rameau's music presents perhaps more varied aspects: he has pieces in the pure tradition of the French suite; imitative pieces (Le Rappel des Oiseaux, La Poule) and character pieces (Les tendres Plaintes, L'entretien des Muses ); pieces of pure virtuosity “à la Scarlatti” (Les Tourbillons, Les trois Mains); and pieces where the searches of the theoretician and the innovator in terms of interpretation are discovered (L'Enharmonique, Les Cyclopes), in which the influence on Daquin, Royer and Duphly is manifest. The pieces are traditionally grouped by tonality, but to see in them the structure of the suite requires a good dose of self-persuasion.

Rameau's three suite books appeared, respectively, in 1706, 1724, and 1728. After this date, he composed only one isolated piece for harpsichord soloist, La Dauphine (1747). Other pieces (such as Les petits marteaux) are doubtfully attributed to him.

During his semi-retirement from 1740 to 1744, he wrote the Pièces de clavecin en concert (1741). Taking up a formula practiced successfully by Mondonville a few years earlier, the concert pieces stand out from the trio sonatas in which the harpsichord is not content with ensuring the basso continuo accompanying the melodic instruments (violin, flute, viola), but rather "concerts" on an equal footing with them. Rameau assured, by the way, that performed on the harpsichord alone, these pieces are also completely satisfactory; This last statement is not very convincing, since he was careful, despite everything, to transcribe five of them: those in which the parts of the instruments that are missing would be the most defective. It is necessary to point out that he also transcribed for the harpsichord a certain number of pieces taken from the Indes galantes .

Lyrical music

From 1733, Rameau devoted himself almost exclusively to lyrical music: what preceded was nothing more than a long preparation. Well equipped with his theoretical and aesthetic principles, from which nothing can separate him, he devoted himself to the complete spectacle that constituted, long before Wagnerian drama, the French lyrical theater. On a strictly musical level, it is richer and more varied than contemporary Italian opera, especially because of the role reserved for choruses and dances, but also because of the musical continuity that arises from the respective relationships between the recitative and the arias. Another essential difference was that while in Italian opera the longer roles were reserved for female sopranos and castrati, in French opera this fashion was ignored.

In Rameau's contemporary Italian opera —the opera seria— the vocal part essentially comprises sung parts —in which music, melody, was king (arias da capo, duets, trios, etc.)— and spoken parts, or almost —the secco recitative—. It was in these where the action progressed —so much so that it was what kept the interest of the spectator waiting for the next aria—; on the contrary, the text in the aria faded almost entirely behind the music, which aspired above all to highlight the virtuosity of the singers.

None of this happens in the French tradition: after Lully, the text must remain understandable, which limits certain procedures such as the «vocalisés», which are reserved for certain privileged words, such as «glory», «victory» — in this sense, and at least in its spirit, the lyrical art from Lully to Rameau was closer to Monteverdi's ideal, music must in principle serve the text—a paradox when comparing Rameau's science of music and poverty of his scripts. A subtle balance is operated between the more or less musical parts, melodic recitative on the one hand, arias often closer to the arioso on the other, ariette lastly, virtuosos, with a more Italian appearance. This continuing musicianship foreshadows even Wagnerian drama more than Gluck's "reformed" opera to appear at the turn of the century.

French-style lyrical scores can be distinguished from five essential components:

- Pieces of «pure» music (obertures, ritournelles, conclusive pieces...). Contrary to the lullysta oberture, so stereotypical, Rameau's oberture is of an extraordinary variety; even when he uses, in his first compositions, the classic "French" scheme; the nato symphonist, the orchestration master, makes a new and unique piece. Some pieces particularly retain attention, such as the overture Zaïs (1748, rev. 1761) describing the detachment of the original chaos, Pigmalion (1748) suggesting the hammer blows of the sculptor on his donkey, or the imposing conclusive chacones of Les Indes gallantes (1735, subsequently revised) or Dardanus (1739);

- Dance arias. The danced intermediates, obligatory even in the context of the tragedy, allowed Rameau to give free course to his inimitable sense of rhythm, melody and choreography, recognized by all his contemporaries, as well as by the dancers. This "wise" musician, always worried about his next treatise, paradoxically chained by dozens of gavotas, minuetos, loures, rigodones, passepieds, tambourins, musettes... According to his biographer Cuthbert Girdlestone:

- "The great superiority of everything related to choreography in Rameau's work has not yet been quite emphasized.", an opinion shared by the German scholar H.W. von Walthershausen, which was explained in 1922, referring to the dances of the dances Zoroastre (1749): "Rameau was the greatest ballet composer of all time. The genius of his work rests on one side on his perfect artistic impregnation of the types of popular dances, and on the other hand, on the permanence of living confrontation with the obligations of choreographic realization, which avoids all distance between the body expression and the spirit of pure music. »

- Coros: Father Martini, a scholar musicographer and coetian of Rameau, said that “the French are excellent in the choirs” (“les Français sont excellents dans les chœurs”), obviously thinking about the latter. Great master of harmony, Rameau likes to compose sumptuous choirs, whether monodic, polyphonic, interspersed by soloist or instrumental interventions and whatever the feelings or passions to which the expression is entrusted.

- Arias. More rare than in the Italian opera, Rameau offers many outstanding examples and always a great originality. Some provoke admiration such as the arias of Télaïre «Tristes apprêts» (Tristes apprêts)Castor et Pollux, 1737), by Iphise «Ô jour affreux», Dardanus “Lieux funestes”, Huascar’s invocations Les Indes gallantes, the final ariette Pigmalion "L'amour qui règne", etc.

- Recitatives. Much closer to Arious. to the recital seccoto which the composer brings both care and the rest to scrupulously respect the French prosody and put his harmonious science to work in order to reflect the effects of passion and feelings.

In the first part of his lyrical career —1733-39— Rameau wrote his great masterpieces for the Académie Royale de Musique: three tragedies set to music and two operas-ballets that still constitute today, the funds of his repertoire. After the interruption from 1740 to 1744, he became an official court musician and composed essentially entertainment pieces, reserving an important role for dance, sensuality, and an idealized pastoral character, before reaching the end of his life., to the great theatrical compositions in a renovated style —Les Paladins (1760) and Les Boréades (1764).

Rameau's librettists

Rameau—unlike Lully who collaborated closely with Philippe Quinault on most of his lyrical works—rarely worked with the same librettist. He was very demanding, bad-tempered and could not maintain long collaborations with his different librettists, with the exception of Louis de Cahusac.

Many Rameau specialists regret that the collaboration with Houdar de la Motte could not take place or that the project of Samson (unfinished, 1733) in collaboration with Voltaire could not be developed, since Rameau only managed to work with second-rate writers. Most of them he met at La Pouplinière's, at the Société du Caveau or at the Comte de Livry's, places where lavish meetings of "high spirits" ("beaux esprits") were held.

None of them could write a text that lived up to their music, and as usual in the genre, the intrigues were often convoluted and disconcertingly ingenuous and lacking in credibility. The versification was not the best, and Rameau had, more than once, to have the librettos modified and the music rewritten after the first performances to correct the most criticized defects: thanks to this, however, it is possible to have two versions of Castor et Pollux (1737 and 1754) and above all, of Dardanus (1739 and 1744). As a curiosity, it can be noted that in Platée (1745) Rameau acquired the rights to Jacques Autreau in order to adapt it to his style.

Theoretical work

Harmony theory

"The need to understand—so rare in the work of artists—is innate in Rameau's work. It is only to satisfy it by what he wrote a treaty of harmony, in which he intends to restore the rights of reason and wants to make the order and clarity of geometry reign in the music... he does not doubt a moment of the veracity of the old dogma of the Pythagoreans... the entire music must be reduced to a combination of numbers; it is the arithmetic of sound, as the optic is the geometry of light. It is seen that it reproduces the terms, but traces the way through which all modern harmony will pass; and he himself». (“Le besoin de comprendre—if rare chez les artistes—ist inné chez Rameau. N'est-ce pas pour y satisfyire qu'il écrivait un Traité de l'harmonie, où il prétend restaurer les droits de la raison et veut faire régner dans la musique l'ordre et la clarté de la géométrie... il ne doute pas un instant de la vérité du vieux dogme des Pythière On voit qu'il en reproduit les termes, mais il y trace le chemin par lequel passera toute l'harmonie moderne; et lui-même»)Claude Debussy

Music theory preoccupied Rameau throughout his career, It could be said that the ideas set forth in his “Traité de l'harmonie réduite à ses principes naturels” —published in 1722 while he was still organist at Clermont-Ferrand cathedral and which placed him as one of the great theoreticians of the time—were already in the process of maturation years before his departure from this town.

It is certain that since the ancient times —from the Greeks and through musicians or scholars such as Zarlino, Descartes, Mersenne, Kircher or Huyghens— the link between mathematical proportions and the sounds generated by vibrating strings or tubes had been established voiced. But the conclusions they had drawn, as far as their application to music was concerned, were elementary and had led to nothing but notions and an abundance of rules tinged with empiricism. Rameau, a systematic spirit, following Descartes —of whom he had read the Discours de la méthode and the Compendium musicae— wanted to free himself from the principle of authority and although he could not get rid of certain presuppositions, he was animated by the desire to make music not only an art, which it already was, but a deductive science in the image of mathematics. Nothing says it better than the following lines:

«Driving from my tenderest youth by a mathematical instinct in the study of an Art for which I was destined, and that my whole life has occupied me exclusively, I have wanted to know the true principle, as the only thing able to guide me with certainty, without regard for the habits or the rules received.» (“Conduit dès ma plus tendre jeunesse, par un instinct mathématique dans l’étude d’un Art pour lequel je me trouvais destiné, et qui m’a toute ma vie uniquement occupgleé, j’en ai voulu connaître le vraçi principe, comme seul capable de me guiderRameau. Démonstration du principe de l’harmoniep. 110.

His first approximation —developed in the 1722 treatise— was purely mathematical and part of the principle that «the string is to the string what the sound is to the sound» (« la corde est à la corde ce que le son est au son"), that is to say that, in the same way that a given string contains twice a chord of half its length, in the same way the low sound produced by the first "contains" twice the higher pitched sound produced by the second. The unconscious presupposition of such an idea is felt -reflected in the verb "to contain"- and, nevertheless, the conclusions that he drew were going to confirm him on this path, especially since he had known, before 1726, the works of Joseph Sauveur on the harmonic sounds that came to corroborate their beliefs in a providential way. In effect, this scientist demonstrated that when a vibrating string or a sound tube -a "sound body"- emits a sound, it also emits, although in a much weaker way, its third and fifth harmonics, which musicians called twelfth and seventeenth degrees diatonic. Presumably the acuity of hearing did not allow them to be clearly identified, but a very simple physical device made it possible to visualize the effect, an important detail, since Sauveur was deaf. It was the irruption of Physics in a domain that until then had been shared by mathematicians and musicians.

Armed with this experience and with the principle of the equivalence of octaves («which are only replicas» («qui ne sont que des replices»), Rameau extracted the conclusion of the "natural" character of the major perfect chord and then, by an analogy that seems obvious although physically unfounded, that of the minor perfect chord.From this discovery were born the concepts of "basse fondamentale", of consonances and dissonances, of inversion («renversement») of the chords, as well as their reasoned nomenclature and modulation, with which he lays the foundations of classical tonal harmony.Afterwards, only practical questions regarding temperament, composition rules, melody and the principles of accompaniment. All this was essential for Rameau, for whom harmony was a natural principle, the quintessence of music. For him, from the emission of a sound, harmony is present; melody, on the contrary, it appears later, and the successive intervals had to conform to the harmony initiated and dictated by the fundamental bass (the "boussole de l'oreille").

The psychophysiological aspect of music was not absent from Rameau's theory either, and it is particularly developed in the “Observations sur notre instinct pour la música et sur son principe”, a pamphlet he published in 1754 in indirect response to Rousseau's “Lettre sur la musique française”. The natural character of harmony, materialized by the fundamental bass, is such that it unconsciously marks our instinct for music:

«... due to little experience, it finds itself the fundamental bass of all the pauses of chanting, according to the explanation given in our "Nouveau Système" (...); what proves even better the empire of the beginning in all its products, since in that case the march of these products reminds the ear of the principle that has determined and suggested accordingly to the composer.This last experience where the only instinct is treated, as in the precedents, proves well that the melody has no other principle than the harmony produced by the sound body: the beginning in which the ear is perhaps concerned, without thinking it, that it is enough to make us find in the field the harmonic background of which this melody depends. (...) there are also many musicians able to accompany an ear a song that listen for the first time.

This ear guide is not another, in fact, that the harmony of a first sound body, which when not surprising enough, presents everything that can follow that harmony and accompany it; and this all consists simply of the fifth, for the least experienced, and in the third, when the experience has already made greater progress.»

(...)Rameau

Rameau was concerned throughout his life, more than anything else, with theory: he wrote many treatises and held many polemics on the subject for more than thirty years: with Montéclair, around 1729; with Father Castel, at first a friend and with whom he ended up falling out, around 1736; with Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the encyclopedists, around 1752; Finally, with D'Alembert, also at first one of his faithful supporters. Likewise, he sought in his epistolary contacts the recognition of his work by the most illustrious mathematicians —Bernoulli and Euler— and the most erudite musicians, especially Father Martini. No passage summarizes all of this better than the one that Rameau dedicates to the resonance of sound bodies:

"How many principles emanated from one alone! Do you need to remind them, gentlemen? From the very resonance of the sound body, the harmony, the fundamental base, the mode, its relations in its attachments, the order or the diatonic genre in which the lesser natural grades of the voice, the greater gender, and the lesser, almost all the melody, the enarmony, the fertile source of one of the most beautiful varieties, the "repossessessessing", or the single cadences,On the other hand, with harmony the proportions are born, and with melody, the progressions, so that these first mathematical principles find themselves here their physical principle in nature.

Thus, this constant order, which we have recognized as a result of an infinity of operations and combinations, precedes here every combination, and every human operation, and presents itself, from the first resonance of the sound body, as nature demands it: thus, what is only an indication becomes principle, and the organ, without the help of the spirit, approves here what the spirit had discovered without the intrusion of the organ; and this must be, that a phenomenon in which nature fully justified and founded the abstract principles. »Rameau, «Démonstration du principe de l'harmonie»

Treaties

The works in which Rameau expounds his theory of music are essentially four:

- Traité de l'harmonie réduite à ses principes naturelsParis (1722).

- Nouveau système de musique théoriqueParis (1726).

- Génération harmonique, Paris (1737).

- Démonstration du principe de l'harmonieParis (1750).

However, his participation in the reflections of a scientific, aesthetic or philosophical nature of his time led him to write many other writings in the form of works, letters, pamphlets, etc., of which we can cite (see Annex at the end of the article):

- «Dissertation sur les différentes méthodes d'accompagnement», Paris (1732).

- «Observations sur notre instinct pour la musique et sur son principe», Paris (1754).

- «Erreurs sur la musique dans l'Encyclopédie», Paris (1755).

- «Code de musique pratique», Paris (1760).

Forgetfulness and recovery

Rameau's plays were performed almost until the end of the Old Regime. All of his works had not been published, but many manuscripts, autographs or not, were collected by Jacques Joseph Marie Decroix and his heirs donated them to the National Library of France, which therefore has exceptional funds.

The "Querelle des Bouffons" continued to be known, with Rameau being attacked by supporters of the Italian opera-buffa. Less is known, however, that some foreign musicians trained in the Italian tradition saw Rameau's music from the end of his life as a possible model for the reform of "opera seria." It was in this genre that Tommaso Traetta composed two operas directly inspired by him, Ippolito ed Aricia (1759) and I Tintaridi (after Castor et Pollux, 1760) after having his scripts translated. Traetta had been advised by Count Francesco Algarotti, one of the most ardent supporters of a reform of the "opera seria" according to the French model, and would have a very important influence on who is generally attributed the title of opera reformer, Christoph Willibald Gluck. Three "reformed" Italian operas by the latter — Orfeo ed Euridice , Alceste and Paride ed Elena — prove that he knew Rameau's work; for example, note that Orfeo and the first version of Castor et Pollux, dating from 1737, both begin with the scene of the funeral of one of the main characters, who must come back to life in the course of the action. In addition, several of the reforms claimed in the preface to Alceste were already practiced by Rameau: he uses the accompanied recitative; the overture to his latest compositions is linked to the action that is to follow. For this reason, when Gluck arrived in Paris in 1774, where he will compose six French operas, it can be considered that he was continuing the tradition of Rameau. But if Gluck's popularity continued after the French Revolution, that was not the case with Rameau. At the end of the XVIII century , his works will disappear from the repertoire for many years.

For much of the 19th century, Rameau's music remained forgotten and ignored, with only a few fragments being performed, some Harpsichord pieces, almost always played on the piano. Despite not being performed, his name retained all its prestige and the musician was not forgotten: Hector Berlioz studied Castor et Pollux and particularly admired Télaïre's aria "Tristes apprêts"; in 1875, at the definitive inauguration of the Paris Opéra —conceived since 1861 by Charles Garnier— Rameau was chosen so that his statue would be one of the four large stone sculptures that preside over the great hall of the Paris Opéra; and, in 1880, the city of Dijon also paid homage to him by erecting his statue.

Unexpectedly, however, it was the French defeat in the war of 1870 that allowed Rameau's music to reemerge from the past. The humiliation suffered on that occasion led some French musicians to search the national heritage for composers of stature capable of comparing themselves with German composers, whose hegemony was then complete in Europe: Rameau was considered of the same stature as his contemporary Johann Sebastian Bach and they began to study his work, which they rediscovered in the sources gathered by Decroix. It was from the 1890s on when the recovery movement accelerated more, with the founding of the Schola Cantorum in Paris —destined to promote French music— and, since 1895, Charles Bordes, Vincent d'Indy and Camille Saint -Saëns undertook the edition of his complete works, a project that was not finished until 1918, with an edition in 18 volumes.

Paul Dukas, in 1903, composed his Variations, Interlude et Finale sur un thème de Rameau for the pianist Édouard Risler. It was also at the beginning of the XX century when one witnessed, for the first time, the revival in concert of some of his works by complete form: in June 1903, La Guirlande, a charming and unpretentious work, was performed at the Schola Cantorum. One of those present was Claude Debussy, who was enthusiastic and shouted: «Vive Rameau, à bas Gluck». The Paris Opéra followed in 1908 with Hippolyte et Aricie, although it was a semi-failure; the work did not attract more than a limited public and had only a few performances.

Castor et Pollux —which had not been performed since 1784— was chosen in 1918, after World War I, for the reopening of the Paris Opera House: Public interest in Rameau's music grew very slowly, and it really accelerated only from the 1950s: in 1952 it was revived, again at the Paris Opéra, Les Indes galantes; in 1956, Platée was programmed at the Aix-en-Provence Festival; in 1957, Les Indes galantes was chosen for the reopening of the Royal Opera of Versailles. Jean Malignon, in his book written at the end of the 1950s, maintained that the public, at that time, already knew Rameau sufficiently, since he had heard his essential compositions.

Since then, Rameau's work has benefited fully from the return in favor of early music. Most of his lyrical work, previously considered untouchable (like many operas of his time), currently has a quality discography performed by the most prestigious baroque ensembles. All of his great works have been revived and always enjoy great success, especially Les Indes galantes . The first performance of his last great tragédie lyrique, Les Boréades, whose rehearsals were canceled on the composer's death in 1764, took place at the Aix-en-Provence Festival in 1982. Finally, the work It was premiered at the Paris Opera in 2003, under the musical direction of William Christie and the stage direction of Robert Carsen.

Contenido relacionado

Lawrence J. Ellison

Don Carlos (opera)

Ambroise thomas

The mercy of Titus (Mozart)

Jose Carreras