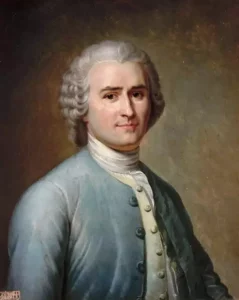

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (June 28, 1712, Geneva; July 2, 1778 Ermenonville) was a French-speaking writer, philosopher and musician from Geneva (Swiss). Orphaned by a very young mother, his life was marked by wandering. His books and letters were very successful from 1749, but they also got him conflicts with the Catholic Church and Geneva politicians which forced him to change residence often and fueled his feeling of persecution.

In the literary field, Jean-Jacques Rousseau enjoyed great success with the epistolary novel Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse (1761), one of the biggest prints of the 18th century. This work seduces its readers at the time with its pre-romantic depiction of love and nature. In Les Confessions (written between 1765 and 1770, with posthumous publication in 1782 and 1789) and in Les Rêveries du promeneur solitaire (written in 1776-78, published in 1782), Rousseau devotes himself to a thorough observation of his intimate feelings. The elegance of Rousseau's writing brought about a significant transformation of French poetry and prose, freeing them from the rigid norms of the Grand Siècle.

Philosophy

In the philosophical field, the reading in 1749 of the question put out to competition by the Academy of Dijon: “Has the restoration of the sciences and the arts contributed to purifying or corrupting mores? » causes what is called « the illumination of Vincennes » . From there are born the works which register Rousseau durably in the world of the thought: the Discourse on sciences and arts (1750), the Discourse on the origin and the bases of the inequality among the men (1755) and Of the contract society (1762).

Rousseau's political philosophy is built around the idea that man is naturally good and that society corrupts him. By “naturally good”, Rousseau means that the human being in the state of nature has few desires, so that he is more fierce than wicked. It's the interactions with other people that make human beings "mean"and lead to growing inequalities. To rediscover natural goodness, man must have recourse to the artifice of the social contract and be governed by laws arising from the general will expressed by the people. For Rousseau, contrary to what Diderot thinks, for example, the general will is not universal, it is specific to a State, to a particular body politic. Rousseau is the first to confer sovereignty on the people. In this, we can say that he is one of the thinkers of democracy (and in particular of direct democracy) even if he is in favor of what he calls elective aristocracy or temperate government in the field of executive power. .

Rousseau is critical of the political and philosophical thought developed by Hobbes and Locke. For him, political systems based on economic interdependence and self-interest lead to inequality, selfishness and ultimately bourgeois society (a term he was one of the first to use). However, if he is critical of the philosophy of the Enlightenment, it is an internal criticism. Indeed, he does not want to return to Aristotle, nor to the old republicanism or to Christian morality.

The political philosophy of Rousseau exerts a considerable influence during the revolutionary period during which his book the Social Contract is “rediscovered” . In the longer term, Rousseau marks the French republican movement as well as German philosophy. For example, Kant's categorical imperative is imbued with Rousseau's idea of the general will. During part of the 20th century, a controversy will oppose those who believe that Rousseau is in some way the father of totalitarianism and those who exonerate him.

According to Claude Lévi-Strauss, Rousseau is the first true founder of anthropology, in particular because the latter would have by his universalism posed "in almost modern terms" the problem of the passage from nature to culture. The historian Léon Poliakov adds that Rousseau invited his contemporaries to travel to distant countries, in order to "study there, not always stones and plants, but once men and customs" .

His body was transferred to the Panthéon in Paris in 1794.

Biography

Family and childhood

Raymond Trousson, in the biography he devotes to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, indicates that the family originated from Montlhéry, near Étampes, south of Paris . The four-grandfather of Jean-Jacques, Didier Rousseau, leaves this city to flee the religious persecution against the Protestants. He moved to Geneva in 1549 where he opened an inn . The latter's grandson, Jean Rousseau, like his son David Rousseau (1641-1738), Rousseau's grandfather, worked as a watchmaker, a respected and lucrative profession at the time.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born onJune 28, 1712at his parents' home on Grand-Rue in the upper town of Geneva. He is the son of Isaac Rousseau (Geneva, 1672 - Nyon, 1747), watchmaker like his father and grandfather, and Suzanne Bernard (Geneva, 1673 - Geneva, 1712), herself the daughter of a watchmaker. named Jacques Bernard . Both of his parents have the status of citizens . They married in 1704, after a first union brought the two families together, Suzanne's brother, Gabriel Bernard, having married Isaac's sister, Théodora Rousseau, in 1699. A first son, François, was born onMarch 15, 1705, then Isaac leaves his wife and newborn in Geneva to go and practice his trade as a watchmaker in Constantinople. He stayed there for six years and returned home in 1711 , long enough to have a second child with his wife, who died of puerperal fever onJuly 7, 1712, nine days after the birth of Jean-Jacques Rousseau .

He spent his childhood raised by his father and a sister of the latter in the house on the Grand-Rue where he was born. This childhood is marked by early reading of novels in the company of his father and the continual mourning of his mother. Following an altercation with a compatriot, Isaac Rousseau took refuge in Nyon in the Pays de Vaud, theOctober 11, 1722to escape justice . He never returned to Geneva, but maintained some contact with his sons, in particular Jean-Jacques who regularly traveled to Nyon and to whom he communicated his passion for books. He entrusts his offspring to his double brother-in-law Gabriel Bernard , an employee in the fortifications who lives in the Geneva district of Saint-Gervais. The latter entrusts him to boarding school with Pastor Lambercier in Bossey at the foot of Salève, south of Geneva, where he spends two years (1722-1724) with his cousin Abraham Bernard. His brother, François, left home very early and we lost track of him in Germany, in the region of Fribourg-en-Brisgau.

His uncle places him as an apprentice with a clerk, then, faced with the child's lack of motivation, with a master engraver, Abel Ducommun. The apprenticeship contract is signed onApril 26, 1725for a period of five years . Jean-Jacques, who until then had known a happy childhood, or at least a peaceful one, was then confronted with harsh discipline . Three years later, theMarch 14, 1728, returning late from a walk outside the city and finding the gates of Geneva closed, he decides to flee, for fear of being beaten again by his master , not without having bid farewell to his cousin Abraham.

Madame de Warens and the conversion to Catholicism

After a few days of wandering, he took refuge for food with the parish priest of Confignon, Benoît de Pontverre. This sends him to a Vaudoise from Vevey, Baroness Françoise-Louise de Warens, recently converted to Catholicism, and who takes care of candidates for conversion. Rousseau falls in love with the one who will later be his tutor and his mistress. The baroness sent him to Turin to the catechumens' hospice of Spirito Santo, where he arrived onApril 12, 1728. Even if he claims in his Confessions to have long resisted his conversion to Catholicism (he is baptized theApril 23), he seems to get used to it quite quickly. He resided in Turin for a few months in semi-idle, living thanks to a few jobs as a lackey-secretary and receiving advice and subsidies from aristocrats and abbots in whom he inspired some compassion. It was during his employment with the Comtesse de Vercellis that the episode of larceny occurred (theft of the pink ribbon belonging to the niece of Madame de Vercellis) for which he cowardly blamed a young cook, Marion, who was , therefore dismissed .

Despairing of being able to rise from his condition, Rousseau discouraged his protectors and resumed, with a light heart, the way to Annecy to find the Baroness de Warens injune 1729. A shy and sensitive teenager, he seeks feminine affection which he finds with the Baroness . He is her “little one” , he names her “Mom” , and becomes her factotum. As he was interested in music, she encouraged him to work with a choirmaster, M. Le Maître, inoctober 1729. But during a trip to Lyon, Rousseau, distraught, abandons Le Maître in the middle of the street, stricken with an epileptic fit. He then wandered for a year in Switzerland, then gave his first music lessons in Neuchâtel inNovember 1730. Inapril 1731, he meets in Boudry a false archimandrite of which he becomes the interpreter until the swindler is rather quickly unmasked .

InSeptember 1731, he returns to M de Warens, who now lives in Chambéry. He meets Claude Anet at her house, a sort of valet-secretary, but who is also the mistress of the house's lover. M de Warens is at the origin of a large part of her sentimental and amorous education. The threesome works somehow until the death of Claude Anet from pneumonia onMarch 13, 1734. "Mom" and Jean-Jacques settle in the summer and fall at Les Charmettes. During these few years, idyllic and carefree according to his Confessions , Rousseau devoted himself to reading, drawing from the important library of M. Joseph-François de Conzié with whom he will create "a store of ideas". A great walker, he describes the happiness of being in nature, the pleasure associated with strolling and daydreaming, to the point of being described as a dromomane. He worked in the administrative services of the cadastre of the Duchy of Savoy, then as a music teacher with the young girls of the bourgeoisie and the nobility of Chambéry. But his health is fragile. “Mom” sent him in September 1737 to consult a professor from Montpellier, Doctor Fizes, about his heart polyp. It was during this trip that he met Madame de Larnage, twenty years older than him, mother of ten children, his true initiator of physical love .

Back in Chambéry, he was surprised to find a new convert and lover, Jean Samuel Rodolphe Wintzenried , with Madame de Warens, and the threesome resumed. In 1739, he wrote his first collection of poems, Le Verger de Madame la baronne de Warens , a grandiloquent poem published in 1739 in Lyon or Grenoble .

First contacts with the world of the French Enlightenment

Rousseau entered the orbit of two important figures of the Enlightenment, Condillac and D'Alembert, when in 1740 he found employment as tutor to the two sons of the Provost General of Lyon, M. de Mably. The latter is the older brother of Gabriel Bonnot de Mably and Étienne Bonnot de Condillac who will both have a literary career . Rousseau composes for the younger of the two sons a Memoir presented to M. de Mably on the education of Monsieur his son . Having thus the opportunity to frequent the good society of Lyon, he won a few friendships there, in particular that of Charles Borde who would introduce him to the capital. Chambéry is close and he can pay a few visits to "Maman", but the links are loose. After a difficult year with his young students, Rousseau agrees with M. de Mably to end the contract . After some time of reflection, he then decided to try his luck in Paris .

In Paris, thanks to a letter of introduction to M. de Boze, he was introduced to Réaumur, which enabled him to submit a memoir presenting his system of musical notation to the Academy of Sciences. This provides for the removal of the scope and replacing it with an encrypted system. The academicians are not convinced by the project which, according to them, would not be new, the inventor being Father Souhaitty. Rousseau persists, improves his project and publishes it at his expense, without meeting the expected success, under the title of Dissertation on Modern Music.. At that time, he became friends with Denis Diderot, just as unknown as him, and received advice from Father Castel. He frequents the salon of Madame de Beserval, and Madame Dupin whom he tries in vain to seduce. She entrusted him for some time with the education of her son Jacques-Armand Dupin de Chenonceaux, in 1743.

In July 1743, Rousseau was hired as secretary to Pierre-François, Comte de Montaigu, who had just been appointed ambassador to Venice. His knowledge of Italian and his zeal make him indispensable to an incompetent ambassador. He appreciates the lively life of Venice: shows, prostitutes and above all Italian music. But the importance he gives to himself makes him arrogant and Montaigu fires him after a year. He returned to Paris on October 10, 1744. This short experience nevertheless allowed him to observe the functioning of the Venetian regime and it was at this time, when he was 31 , that his interest in the Politics. He then conceived the project of a great work whichbut which will become the famous On the social contract . He works there from time to time for several years .

He then moved to the Hôtel Saint-Quentin, rue des Cordiers, where he moved in with a young laundrywoman, Marie-Thérèse Le Vasseur, in 1745. The latter brought him the affection he lacked. He married her civilly in Bourgoin-Jallieu onAugust 30, 1768. Jean-Jacques must then support not only a talkative woman but also her family . Between 1747 and 1751 five children were born, whom Jean-Jacques Rousseau, perhaps at the insistence of Marie-Thérèse's mother , placed in the Foundling Children's Service, the public assistance of the time. He first explains that he does not have the means to maintain a family , then in book 8 of the Confessions , he writes that he delivered his children to public education considering this an act of citizenship, of father, and admirer of the ideal Republic of Plato. To the next book of Confessions, he also writes that he made this choice mainly to remove his children from the influence of his in-laws, whom he considered harmful. This decision will be reproached to him later by Voltaire, when he poses as a pedagogue in his book Émile , and also by those he calls the "Holbachic coterie" (the entourage of D'Holbach, Grimm, Diderot, etc. .). However, some of his friends, including Madame d'Épinay before she fell out with him, had offered to adopt these children .

In May 1743, he began composing a heroic ballet, Les Muses galantes , excerpts from which were presented in Venice in 1744 . an apprentice, others a plagiarist” . For Fontenoy's victory, he contributed to the creation of the Voltaire-Rameau duo's comedy-ballet, les Fêtes de Ramire , based on La Princesse de Navarre by Voltaire accompanied by music by Rameau. He earned his living by exercising the functions of secretary, then tutor with the Dupins from 1745 to 1751. The circle of his frequentations included Dupin de Francueil, his mistress Louise d'Épinay, Condillac, D'Alembert, Grimm and above all Denis Diderot. In 1749, Diderot invited him to participate in the great project of the Encyclopédie by entrusting him with the articles on music .

Fame and torment

First great works

In 1749, the Academy of Dijon put the question "Has the progress of science and the arts contributed to corrupting or purifying morals?" Encouraged by Diderot, Rousseau took part in the competition . His Discourse on the sciences and the arts (known as the First Discourse ), which maintains that progress is synonymous with corruption, obtains the first prize, inJuly 1750. The work was published the following year and its author immediately gained international fame . This speech arouses many reactions; no less than 49 observations or refutations appeared in two years, including those of Charles Borde, the Abbé Raynal, up to Stanislas Leszczynski or Frédéric II, which enabled Rousseau to refine his arguments in his answers and provided him with growing notoriety .

He then abandoned his jobs as secretary and tutor to become independent, and lived thanks to his work of transcription of musical scores ; he adopts a physical and sartorial attitude more in harmony with the ideas developed in the Discourse . But it is these ideas that will gradually distance him from Diderot and the philosophers of the Encyclopédie .

theOctober 18, 1752, his one-act interlude, Le Devin du village , is performed before King Louis XV and the Pompadour, at Fontainebleau. The opera was a success, but Rousseau shied away from the presentation to the king the next day, thereby refusing the pension that could have been granted to him . He had his play Narcisse performed immediately after , to which Marivaux had made a few alterations .

This year 1752 sees the beginning of the Quarrel of the Bouffons. Rousseau took part in it with the encyclopaedists by writing his Letter on French Music , in which he affirmed the primacy of Italian music over French music, that of melody over harmony, scratching Jean-Philippe Rameau in passing.

In 1754, the Academy of Dijon launched another competition to which he responded with his Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men (also called Second Discourse ), which completed his fame. Rousseau defends there the thesis according to which the man is naturally good and denounces the injustice of the company . The work arouses, like the Premier Discours , a lively controversy on the part of Voltaire, Charles Bonnet, Castel and Fréron in particular. Without waiting for the result of the competition, he decides to recharge his batteries in Geneva, not without paying a visit to his old friend, Mrs. of Warrens. Famous and admired, he is well received. In the field of ideas, Rousseau moves away from atheistic encyclopaedists who believe in progress, while he advocates virtue and love of nature. He remains fundamentally a believer, but abjures Catholicism and reintegrates Protestantism, thereby becoming a citizen of Geneva again . However, there are only a few months left in the city. On October 15 , he is again in Paris.

Great works and social integration

Rousseau no longer addressed himself only to bourgeois society like the court artists or scholars of previous centuries. He never ceases to address another audience, different from that of the high society that haunts literary salons. Gradually, his celebrity becomes "disastrous" in his own words, this celebrity that he sought as a social weapon turns against him, and he enters a paranoia, confronted with the public figure that "Jean-Jacques" has become. , the one that people want to see, meet and whose portraits circulate . Inapril 1756, Mme d'Épinay put the Hermitage, a small house on the edge of the Montmorency forest, at her disposal. He moved there with Thérèse Levasseur and her mother, then began to write his novel Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse and his Dictionary of Music . He also undertook, at the request of M d'Épinay, the formatting of the works of the Abbé de Saint-Pierre. At the beginning of 1757, Diderot sent Rousseau his drama Le Fils naturel , in which is found the phrase "The good man is in society, only the wicked are alone" . Rousseau takes this line for a disavowal of his choices and he

During the summer, Diderot had difficulty getting the Encyclopédie published in Paris. His friends Grimm and Saint-Lambert are enlisted in the Seven Years' War. They entrust the virtuous Rousseau with their respective mistresses, Madame d'Épinay and Madame d'Houdetot. Jean-Jacques falls in love with the latter, leading to a probably platonic idyll, but, due to clumsiness and indiscretions, rumors spread well into the lover's ears. Rousseau successively accuses his friends Diderot, Grimm and M d'Épinay who will definitely turn their backs on him . M d'Épinay informed him of his dismissal, and he had to leave the Hermitage in December. He moved to Montmorency where he rented the house which would become his museum in 1898.

In his Letter to M. d'Alembert (1758) he opposed the idea defended by the latter that Geneva would benefit from building a theatre, arguing that this would weaken the citizens' attachment to the life of the city .

Isolated in Montmorency and suffering from stone disease, he became gruff and misanthropic. However, he won the friendship and protection of the Marshal of Luxembourg and his second wife. However, he remains very jealous of his independence, which leaves him time to exercise an intense literary activity. He completed his novel Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse , which was a huge success , and worked on his essays Émile ou De l'éducation and Du contrat social . The three works appeared in 1761 and 1762, thanks to the kindness of Malesherbes, then director of the Bookstore. In The Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar , placed at the heart of Émile, Rousseau refutes the atheism and materialism of the Encyclopedists as much as the dogmatic intolerance of the devout party. In The Social Contract , the foundation of political society rests on the sovereignty of the people and civic equality before the law, an expression of the general will. This last work will inspire the pre-revolutionary ideology. If Émile and the Social Contract mark the peak of Rousseau's thought, they nevertheless isolate their author. Indeed, the Parliament of Paris and the authorities of Geneva consider that they are religiously heterodox and condemn them . Threatened with body capture by the Grand Chamber of the Paris Parliament injune 1762, he must flee France alone, with the help of the Marshal of Luxembourg; Thérèse will join him later. He avoids Geneva and takes refuge in Yverdon with his friend Daniël Roguin. If his condemnation in Paris is mainly due to religious reasons, it is the political content of the Social Contract that earned him the hatred of Geneva. Bern follows Geneva and issues an expulsion decree. Rousseau must leave Yverdon and goes to Môtiers with Madame Boy de la Tour. Môtiers is located in the principality of Neuchâtel which comes under the authority of King Frederick II of Prussia. The latter agrees to grant hospitality to the outlaw .

Facing religions and Voltaire

The misfortunes of Rousseau did not soften the philosophers and those continue to overwhelm it, in particular Voltaire and D'Alembert. Physically, the disease of the stone makes him suffer and he must be regularly probed. It is then that he adopts a long Armenian garment, more convenient to hide his affection . He went back to writing a melodrama, Pygmalion , then a sequel to L'Émile , Émile et Sophie, ou les solitaires which remained unfinished.

Émile is put on the Index inseptember 1762and Christophe de Beaumont, Archbishop of Paris, launches an anathema against the ideas professed by Le Vicaire Savoyard . Rousseau answers it with a Letter to Christophe de Beaumont which will appear inMarch 1763, libel directed against the Roman Church . However, his voluntarily “anti-papist” tone did not calm the ardor of the Protestant pastors of Geneva who waged a silent struggle against Jean-Jacques' friends, who sought in vain to rehabilitate him. Tired, Rousseau will end up giving up theMay 12, 1763to Geneva citizenship . In the meantime, he developed a passion for botany and had his Dictionary of Music published , the fruit of sixteen years of work.

The conflict became political with the publication of the Lettres de la campagne by Jean Robert Tronchin, Attorney General to the Petit Conseil de Genève, to which Rousseau replied with his Lettres de la montagne , in which he took a position in favor of the General Council, representing the people. sovereign, against the right of veto of the Small Council . The letters are published indecember 1764, but are burned in The Hague and Paris, prohibited in Bern. This is the moment that Voltaire chooses to anonymously publish Le Sentiment des citoyen where he publicly reveals the abandonment of Rousseau's children. The pastor of Môtiers, Montmollin, who had welcomed Jean-Jacques on his arrival, then sought to excommunicate him with the support of the “Venerable Class of his colleagues from Neuchâtel”. But Rousseau is protected by a rescript of Frederick II. However, he passes for a seditious and the population rounded up by Montmollin becomes so threatening that, theSeptember 10, 1765, Jean-Jacques took refuge temporarily on the island of Saint-Pierre on Lake Biel, from where the Bernese government expelled him on 24 October . Before leaving, Jean-Jacques Rousseau gave his friend Du Peyrou a trunk containing all the papers he had (manuscripts, drafts, letters and copies of letters) .

Years of wandering

Rousseau, therefore, lives in the fear of a plot directed against him and decides to begin his autobiographical work in the form of justification. He goes to Paris where he stays in November anddecember 1765to the Temple which benefits from extraterritoriality. Rousseau is also under the protection of the Prince of Conti who allows him to receive distinguished visitors . At the invitation of David Hume, attached to the British Embassy in Paris, he went to England onJanuary 4, 1766. Thérèse joins him later. During his stay in England his mental instability grows and he convinces himself that David Hume is at the center of a plot against him . It was at this time that a false letter from the King of Prussia, addressed to Rousseau, circulated in Parisian salons. She is well-turned but uncharitable towards him. The author is Horace Walpole, but Rousseau first attributes it to D'Alembert, then suspects Hume of being involved in the plot. Hume frequented the Encyclopedists in Paris who were able to warn him against Rousseau. The latter, hypersensitive and suspicious, feels persecuted. After six months of stay in England, the break is complete between the two philosophers, each justifying himself by public writings, which generates a real scandal in the European Courts. Rousseau's enemies, in the forefront of which Voltaire, are jubilant, while his friends, who pushed him to entrust his destiny to Hume, are dismayed by the turn of events.

During his stay in England, he resided inMarch 22, 1766toMay 1 , 1767at Richard Davenport who made available to the citizen of Geneva his property of Wootton Hall in Staffordshire. It was there that he wrote the first chapters of the Confessions . The way he treats Diderot, Friedrich Melchior Grimm in his writings attests to his paranoia .

InMay 1767, still under threat of condemnation by Parliament, Rousseau returned to France under the assumed name of Jean-Joseph Renou, the maiden name of Thérèse's mother . For a year, he was hosted by the Prince de Conti at the Château de Trye, near Gisors in the Oise. The stay is particularly agonizing for Rousseau who comes to suspect his friends, including the faithful DuPeyrou who has come to visit him .

theJune 14, 1768, he leaves Trye and will wander for some time in Dauphiné around Grenoble. Thérèse joined him in Bourgoin where on August 29 and, for the first time, he presented her to the mayor of the town as his wife . He resumed his name and moved to the Monquin farm in Maubec. He decides to leave the Dauphiné onApril 10, 1770, stays a few weeks in Lyon, and arrives in Paris onJune 24, 1770where he stayed at the Hotel Saint-Esprit, rue Plâtrière.

In Paris, he survived thanks to his work as a copyist of musical scores. He organizes readings of the first part of the Confessions in private salons in front of silent and embarrassed audiences faced with this naked soul . His old friends fearing revelations, M d'Épinay had these readings banned by Antoine de Sartine, then lieutenant general of police.

In Considerations on the Government of Poland , which he wrote at the time, he condemned the Russian policy of dismantling Poland. This position increases its marginality, most philosophers of the French Enlightenment then admiring Catherine II. He continued writing the Confessions and began writing the Dialogues, Rousseau judge of Jean-Jacques . Unable to publish them without arousing new persecutions, he tried to place the manuscript on the altar of Notre-Dame, but the closed gate prevented him from accessing it. In desperation, he goes so far as to distribute tickets to passers-by justifying his position .

It was also the time when he botanized, an activity he shared with Malesherbes, which brought the two men closer together. He writes to the address of Mrs. Delessert, in the form of letters, a course of botany intended for his daughter Madelon, the Letters on the botany . The Reveries of the Solitary Walker , an unfinished work, were written during his last two years, between 1776 and 1778. These last works would not be published until after his death. On this date, he also maintained a correspondence with the opera composer Gluck.

Death

In 1778, the Marquis de Girardin offered him hospitality, in a pavilion on his estate at the Château d'Ermenonville, near Paris; it is there that the philosophical writer dies suddenly theJuly 2, 1778, from what appears to have been a stroke. Some have advanced the hypothesis of a suicide, creating a controversy on the circumstances of the death of the philosopher .

The day after his death, the sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon molds his death mask. On July 4 , the Marquis René-Louis de Girardin had the body buried on the Île des Peupliers on the property. The tomb hastily erected by the Marquis de Girardin was replaced in 1780 by the current funerary monument designed by Hubert Robert, executed by J.-P. Lesueur: a sarcophagus sculpted on all four sides with bas-reliefs representing a woman nursing and reading the Émile , as well as several allegories of liberty, music, eloquence, nature and truth . On the pediment, a cartouche from which hangs a garland of palms bears Rousseau's motto " vitam impendere vero (“dedicate his life to the truth”). The north face bears the epitaph “Here lies the man of Nature and Truth”. The philosopher is quickly the object of a cult, and his tomb is assiduously visited .

His intellectual journey

The great sensitivity of Rousseau deeply marks his work and explains, in part, the estrangements which marked out his life. David Hume said of him : “All his life he did nothing but feel, and in this respect his sensitivity reaches heights going beyond what I have seen elsewhere; this gives him a more acute feeling of pain than of pleasure. He is like a man who was stripped not only of his clothes, but of his skin, and found himself in this state to fight with the coarse and tumultuous elements . Bertrand Russell added : "It is the most sympathetic summary of his character which is almost compatible with the truth" .

Rousseau's philosophy in context

Rousseau did not take a philosophy course. Self-taught, it was his reading, in particular that of his immediate predecessors: Descartes, Locke, Malebranche, Leibniz, the Logic of Port-Royal and the naturalists, which enabled him to become a philosopher. From the first work that made him famous, the Discours sur les sciences et les arts , Rousseau claimed not to be a philosopher by profession and expressed his distrust of some of those who call themselves philosophers. He writes about this:

"There will always be men made to be subjugated by the opinions of their century, their country, their society: such is the strong mind and the philosopher today who, for the same reason, he would have been only a fanatic in the time of the League. One must not write for such readers, when one wishes to live beyond one's century . »

Three aspects of Rousseau's thought are particularly noteworthy :

- first of all, Rousseau is the first great critic of political and philosophical thought as it unfolds from the end of the 17th century. Contrary to Bacon, Descartes, Locke, Newton, he maintains that what they call "progress" is first of all a decline in virtue and happiness, that the political and social systems of Hobbes and Locke based on the economic interdependence and self-interest lead to inequality, selfishness and bourgeois society (a term he was one of the first to use) ;

- then, if Rousseau is a critic of the political and philosophical theory of his time, his criticism comes from within. He does not want to return to Aristotle, nor to the old republicanism, nor to Christian morality because, while he accepts many of the precepts of the individualist and empiricist traditions of his time, he draws different conclusions from them by asking himself different questions. For example: is the state of war of all against all primary or is it just an accident of history? Can't human nature be molded to arrive at a democratic state ?

- finally, Rousseau is the first to think that democracy is the only legitimate form of state .

In his political writings, Rousseau places himself in the continuity of Bodin, which he interprets using “the philosophical and legal theory of modern natural law” . For him, Grotius and Pufendorf as well as Locke made the mistake of thinking that the passions were natural when they are only the products of history. For Rousseau, the necessary satisfaction of primary needs (food, shelter, etc.) which permeates so strongly the history of men, tends to isolate them. It does not bring them together, as with Pufendorf, nor does it stir up their discord, as with Hobbes .

Taking a stand against Grotius and Hobbes that freedom can be alienated because life is first, Rousseau argues in Du contrat social , that freedom is inalienable because life and freedom are synonymous . Similarly, whereas in Hobbes, the people are constituted thanks to the terror exercised over them by power, in Rousseau, the people are constituted thanks to a social pact which establishes their political unity . Contrary to what Locke, Spinoza or Hobbes think, for Rousseau, once the pact is made, the human being loses all natural rights . On this point, he is opposed to the school of natural law of Pufendorf, Grotius, Burlamaqui, Jean Barbeyrac, who conceive of "political law, as the law of civil societies". What Rousseau is looking for is not the law of civil societies, but the law of the State.

The "illumination of Vincennes" , the first two speeches and the Enlightenment

The Illumination of Vincennes and the Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts

In 1749, during a visit to Diderot, then imprisoned in Vincennes, Rousseau read in the Mercure de France that the Academy of Dijon had launched a competition on the following question: "The restoration of the sciences and the arts has Did it contribute to purifying or corrupting mores ? This reading provoked in him what is usually called the " illumination of Vincennes" , an event which would profoundly change the course of his life: "All of a sudden, he wrote, I felt the dazzled spirit of a thousand lights; crowds of ideas presented themselves there with both a force and a confusion that threw me into inexpressible confusion .

In the text he writes for this competition , Rousseau opposes Montesquieu, Voltaire and Hume who see modernity and the improvement of the arts and sciences as extremely positive . The citizen of Geneva made the re-establishment of the arts begin "with the fall of the throne of Constantine" , that is to say with the fall of the Byzantine Empire, "which carried into Italy the remains of ancient Greece » . Rousseau, influenced by the thought of the ancient classics, such as Livy, Tacitus or Plutarch, “raises an indictment against modern society and artifice” . Its models among the Ancients are Sparta and the Roman Republic, from the time when it was "the temple of virtue" before becoming, under the“the theater of crime, the reproach of nations and the plaything of barbarians” . The anti-model is constituted by the City of Athens in the century of Pericles, which he finds too mercantile, too focused on literature and the arts, all things which, according to him, lead to the corruption of morals .

Rousseau's thought revolves around three axes: the distinction between useful sciences and arts and those which he considers useless, the importance given to genius, the opposition to luxury which corrupts virtue. Regarding the first point, Rousseau gives the arts and sciences an unflattering origin: “Astronomy was born of superstition; eloquence, ambition, hatred, flattery, lies; all, and even morality, from human pride. The sciences and the arts therefore owe their birth to our vices . However, he distinguishes the useful sciences and arts, those which relate to things and which relate to trades, to the manual work of men (in the 18th century, in France, manual work is despised) with the sciences and abstract arts only motivated by the search for worldly success . The important thing, with Rousseau, is virtue, "sublime science of simple souls" whose principles are "engraved in all hearts" and whose laws one learns by listening to "the voice of one's conscience in the silence of the passions. » .

In accordance with his conception of the link between art or science and virtue, Rousseau distinguishes between genius, which does not allow itself to be corrupted by the world, and the worldly. Addressing Voltaire, he wrote: "Tell us, famous Arouet, how many strong, masculine beauties you have sacrificed to your false delicacy, and how much the spirit of gallantry, so fertile in small things, has cost you great things. » . In general, he believes that the geniuses (Bacon, Descartes, Newton) were able to focus on the essentials and contributed to the improvement of human understanding: "it is to this small number that it belongs to 'raise monuments to the glory of the human spirit' .

Rousseau sees an antinomy between luxury, which he associates with commerce and money, and virtue: “The old politicians spoke constantly of mores and virtue; ours speak only of trade and money” . For Rousseau, luxury leads to the development of inequalities and the depravity of morals. On this point, he is in opposition to the major current of his century represented by people like Mandeville or Voltaire who, in the Mondain , pleads in favor of the superfluous, or even by the physiocrats or by David Hume who sees in luxury a spur to economic activity . The citizen of Geneva, aware of this opposition, notes:

“Let luxury be a sure sign of wealth; let it even serve to multiply them: what are we to conclude from this paradox so worthy of being born in our day; and what will become of virtue, when it is necessary to get rich at any cost ? »

Discourse on the origin of inequality among men

In 1755 Rousseau published the Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men . For Jean Starobinski, Rousseau in this work "recomposes a philosophical "genesis" in which neither the Garden of Eden, nor the fault, nor the confusion of languages is missing, a secularized, "demystified" version of the history of origins, but which, supplanting Scripture, repeats it in another language .

Rousseau imagines what humanity could have been like when Man was good: it's the state of nature that perhaps never existed. This is called a conjectural story based on a conjecture, that is to say on a hypothesis . From this basis, he explains how the naturally good Man became evil. According to him the Fall is not due to God (he supposes it good), nor to the nature of Man, but to the historical process itself, and to the political and economic institutions that emerged during this process.. In Rousseau, evil designates both the torments of the mind that preoccupied the Stoics so much, but also what the Moderns call alienation, that is to say the extreme attention that men pay to the gaze of others. . Attention that diverts them from their inner self, from their nature .

Rousseau ends his speech by defining, on the one hand, his vision of equality where the inequality of conditions must be proportionate to the inequality of talents, and by noting, on the other hand, that Man cannot go back, that the state of nature is definitely lost .

Change of life (1756-1759)

During this period, Rousseau felt the need to change his life and follow the precept that he now included in many texts " vitam impedere vero (dedicate his life to the truth)" . First, he changes his outfit. “I left the gilding and the white stockings; I took a round wig; I laid down the sword; I sold my watch saying to myself with incredible joy: Thank Heaven, I will no longer need to know what time it is.. In addition, he left the city to settle in the countryside, first at the Hermitage in the forest of Montmorency, then in the house of Petit Mont-Louis. Finally, he refuses the places and incomes offered to him. To remain free, he earns his living by working as a music copyist. He also breaks the strong bond that had existed between him and Diderot since 1742 .

For Jean Starobinski, the ostentatious poverty of Rousseau has a double aim. It is first of all a “demonstration of virtue in the Stoic or cynical way” intended to alert consciences, to show the social inequality then very strong. Moreover, it is a manifestation of Rousseau's loyalty to his social origin . Still according to this author, Rousseau had the genius to conform to a principle very much like Plutarch, which he stated in a letter addressed to his father when he was only nineteen: "I consider better an obscure freedom than a brilliant slavery .

The Social Contract and Emile

The works Du contrat social and Émile ou De l'éducation were both published in 1762. They were condemned almost immediately. In France, the condemnation emanates from both the Parliament (Ancien Régime) and the faculty of theology. In Geneva, it is the work of the Petit Conseil. These convictions will have heavy consequences for Rousseau insofar as they force him to a life of wandering. If the French Revolution contributed to making the Social Contract his most esteemed work in France, the German tradition preferred the Second Discourse and the Émile .

Of the social contract

Initially, Rousseau wanted to write a book called Political Institutions . Then, he abandons this project because he considers it already treated by Montesquieu. He then undertook to write a book turned towards the nature of things and which would thereby be able to found political law . Comparing Montesquieu's book and his own, he writes in Émile , “the illustrious Montesquieu … contented himself with treating of the positive law of established governments; and nothing in the world is more different than these two studies” . The Social Contract indeed aims to found both political law and the State. According to Mairet, what gives this book its unique status is that, like Plato, it“establishes from the outset the link between truth and freedom” .

The notion of social contract should not be understood as designating a formal contract between individuals but as the expression of the idea according to which, "legitimate power to govern is not directly based on a divine title or on a right natural to govern, but must be ratified (“authorized”) by the consent of the governed” .

In Du contrat social Rousseau seeks to answer what he thinks to be the fundamental question of politics, namely: how to reconcile the freedom of citizens with the authority of the State based on the notion of sovereignty which he takes up from Bodin . For Gilles Mairet, the radical novelty of the Social Contract comes from the fact that it affirms both that the people are sovereign and that the republic is a democracy . In this work, Rousseau wants absolutely to avoid that the human beings are subjected to the arbitrary one of the chiefs, this is why, as it indicates it in a letter of theJuly 26, 1767addressed to Mirabeau, its aim is to “find a form of government which puts the law above men” . Rousseau wants to combine political idealism and anthropological realism. He writes on this subject: “I want to find out if, in the civil order, there can be some rule of legitimate and safe administration, taking men as they are and the laws as they may be. I will always try to combine, in this research, what the law allows with what the interest prescribes, so that justice and utility are not divided .

The Social Contract comprises four books. The first two are devoted to the theory of sovereignty and the last two to the theory of government .

Émile, or Education

This work, begun in 1758 and published in 1762 at the same time as the Social Contract, is both one of the most important treatises on education and one of the most influential . The work is in line with The Republic of Plato and The Adventures of Telemachusby Fénelon, who mix politics and education (Rousseau particularly quotes Plato's dialogue, presenting it as a work of education that one would have been wrong to judge according to the title). Few things dispose Rousseau to write a work on education. If he was tutor to the children of Mably (the brother of Condillac and the Abbé de Mably), the experience seems not to have been very conclusive. Moreover, as Voltaire was sure to point out, Rousseau abandoned his five children, born between 1746-1747 and 1751-1752, at the foundling hospice , although he encouraged parenthood (women in to make children and fathers to take care of the education of their children)

The book is based on Rousseau's fundamental conception that Man was born good but society has corrupted him. Thus he posits as an “indisputable maxim that the first movements of nature are always straight: there is no original perversity in the human heart. There is not a single vice of which one cannot say how and from where it entered into it” . Rousseau divides the education of human beings into five phases corresponding to the five books of Émile. Book I deals with newborns, Book II with children from 2 to 10/12 years old, Book III with 12 to 15/16 years old, Book IV with puberty dominated by conflicts between reason and passions, while also dealing with questions of metaphysics or religion in a section known asThe Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar and which has been published separately. Finally Book V deals with the young adult at the time when he is initiated into politics and takes on a companion .

In connection with his conception of the human person, education must first be negative , that is to say that we must not begin by instructing because by doing so we risk perverting human nature: "The first education must therefore be purely negative. It consists, not in teaching virtue or truth, but in safeguarding the heart from vice and the spirit from error . He rightly criticizes John Locke, in his Thoughts on Education (1693), for wanting to consider the child too early as a reasonable being and for wanting to use education to transform the child into a man, rather than leaving the 'child being a child, waiting for him to grow up and become an adult in a natural way. For Rousseau, it is only at the time of puberty that education should provide moral training and enable the adolescent to integrate into the social world.

Rousseau and religion

Three groups of texts are to be taken into account to understand Rousseau's relationship to religion:

- the "theoretical", or "dogmatic" writings, such as the Letter to Voltaire on Providence , Book IV of Émile entitled Profession of faith of the Savoyard vicar , added in extremis to the work, shortly before printing; the 8 and last chapter of the Social Contract , also added at the last moment at the end of the book (this chapter 8 is the longest of the whole book); finally, La Nouvelle Héloïse . It will be noted that these last three works were published at the same period (1762-1763);

- the writings of justification or polemic: the Letter to Christophe de Beaumont , the Letters written from the mountain and the Dialogues ( Rousseau judges Jean-Jacques );

- private correspondence, notably the letters to Paul Moultou and the letter to Franquières of 1769 .

Rousseau's Christian faith is a kind of rationalist deism, inherited from Bernard Lamy and Nicolas Malebranche: there is a god because nature and the universe are ordered. Rousseau is not a materialist (see the Letter to Franquières ), but he is neither an Orthodox Protestant nor a Roman Catholic. However, he calls himself a "believer" , including in his letter ofFebruary 14, 1769to Paul Moultou, who seems eager to renounce his faith, and whom he urges not to “follow fashion” .

In particular, Rousseau does not believe in original sin, a doctrine which incriminates human nature and which he fought for a long time. He speaks with irony of this sin "for which we are very justly punished for the faults we have not committed" (Memoir to M. de Mably) . If he rejects this doctrine, it is for theological reasons, for he sees in the implications of this dogma a harsh and inhuman conception, which "much obscures the justice and goodness of the Supreme Being"; but it is also because, feeling good, he cannot conceive of being affected by a secret defect . This position will lead him to forge the fiction of a “state of nature”, extra-moral and extra-historical, to rule out all the facts of history.

Rousseau seen by himself

By way of autobiography, Rousseau wrote three works: The Confessions , Rousseau judge of Jean-Jacques , and the Reveries of the solitary walker , work which it will not complete.

The writing of the Confessions spans from 1763 or 1764 to 1770. If Rousseau presents in this work his past faults, such as the episode of the stolen ribbon , the Confessions are less confessions in the Augustinian sense than a kind of self-portrait à la Montaigne. The object of the book “is to make known exactly my interior in all the situations of my life. It is the story of my soul that I promised” .

He wrote Rousseau judge of Jean-Jacques during the period from 1772 to 1776. The work appeared partially in 1780 and aroused a certain uneasiness because Rousseau there denounced a plot which would be led against him by Grimm, Voltaire, D'Alembert and David Hume. In this writing, Rousseau dialogues with Jean-Jacques who represents Rousseau as his enemies see him and a third character called "the Frenchman" who represents public opinion, that is to say someone who has no neither met Rousseau nor read his books. It is this character that he wants to convince .

The Reveries of the Solitary Walker were written between 1776 and 1778, until Rousseau's death. If in this book, life is "constituted as a philosophical object" , contradictions are visible between his political project which aims to integrate the citizen into political life and Rousseau's deep inclination. He writes "[...] I have never been really suitable for civil society where everything is embarrassment, obligation, duty, and [..] my independent nature always made me incapable of the subjugation necessary for whoever wants to live with the men” .

The status of these texts poses a problem. For Alexis Philonenko, Rousseau's philosophy “in the face of the obstacle has flowed back towards a theory of individual existence” . On the contrary, for Géraldine Lepan, these works "can be read as the necessary complement to the 'sad and great system' resulting from the Illumination of Vincennes" . The objective would always be the same: “to reveal the self beneath social deformations” .

Human nature and conjectural history in Rousseau

Conjectural history

According to George Armstrong Kelly, Rousseau approaches the puzzle of history in the most antithetical way possible: the moral aspect. For Rousseau, history is both a collection of examples and a succession of states of human faculties which evolve according to the challenges of time . History, for the citizen of Geneva, is never a starting point, but on the contrary the means of extending a tension which is specific to him to humanity seen as a whole. The philosopher does not use the data to question their meaning, he uses them to support his own convictions . In the Emile, Rousseau defends the idea that our impressions of the past should be used for educational purposes, and not to cultivate theoretical knowledge. On this point, he stands out from Jean le Rond D'Alembert who had a more objective view of history which he saw as giving posterity a dispassionate spectacle of vices and virtues . On the contrary, Rousseau writes in his History of Lacedemone :

"I care very little that I am reproached for having lacked that serious coldness recommended to historians [...] as if the main utility of history was not to make all its good people love ardently. and hate the bad guys . »

For Jean Starobinski, in a way, conjectural history in Rousseau aims to offer an alternative history to that of Christianity. This author notes that, in the Second Discourse , “Rousseau recomposes a philosophical “genesis” in which neither the Garden of Eden nor fault nor the confusion of languages is missing. Secularized, "demythologized" version of the story of origins, but which, by supplanting Scripture, repeats it in another language . So the state of nature can be seen as an imaginary reconstruction that replaces the biblical myth of the Garden of Eden in the Book of Genesis. At the beginning of the v century, the expulsion of men from the earthly paradise—for having eaten the forbidden fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil—inspired the Christian theologian Augustine of Hippo with the doctrine of original sin. Even if he rejected this one, Rousseau refers to it explicitly in note 9 of the Second Discourse .

For Victor Goldschmidt, Rousseau radicalizes the conjectural method used by his contemporaries by considering as a certain fact that the state of nature existed. Its main problem is to explain the passage from this natural state to civil society by purely natural causes based on physical (health and biological equality), metaphysical (perfectibility and a purely virtual freedom) and moral (love of self, pity and love) .

From the state of nature to civil or political society

Like Thomas Hobbes and John Locke and other thinkers of the time, but unlike Plato, Aristotle, Augustine of Hippo, Nicolas Machiavelli and others, the starting point of Rousseau's philosophy is the state of nature. But Rousseau does not consider the men who in his time lived in tribes in America as being in a state of nature: for him, they are at a more advanced stage. To think of the human being in the natural state, you have to go back further and imagine something that perhaps never existed. Rousseau writes that he will consider the human being "as he must have come out of the hands of Nature" , in doing so he writes "I see an animal less strong than some, less agile than others, but take it all,

According to Victor Goldschmidt, there is first a passage from the natural state to the natural society which he also calls "youth of the world" without "foreign impulse" only because "the movement imprinted in the state of nature continues on its own . On the other hand, the transition from natural society to civil society is explained by several foreign impulses. First of all, the development of agricultural and metallurgical techniques leads to the appropriation and division of tasks. In addition, extraordinary natural phenomena such as volcanic eruptions change the physical environment of men. All these upheavals lead to an exacerbation of human passions. So, to avoid the worst, man must make an unnatural decision and enter into a social contract. For Jean Starobinski, the passage from the state of nature to the civil society before the social contract takes place in four phases:

- the idle man living in a dispersed habitat who little by little joins together in a horde ;

- the first revolution: humanity enters the patriarchal order and families can regroup. For Rousseau, this period is that of the golden age ;

- the patriarchal order gives way to a world marked by the division of tasks which causes man to lose his unity. The most violent or the most skilful become the rich and the others the poor ;

- the war of all against all understood by Rousseau in a Hobbesian sense.

At the end of this process, the establishment of a social contract makes it possible to emerge from the state of war and to achieve a civil society marked by inequality. Jean Starobinski writes on this subject: “stipulated in inequality, the effect of the contract will be to consolidate the advantages of the rich, and to give inequality the value of an institution” . In The Social Contract , Rousseau seeks to get out of this first unequal social contract through the concept of general will which will allow, according to the expression of Christopher Bertam, "each person to benefit from the common force while remaining as free as they were in the state of nature”. In short, for Rousseau the State is the way out of the evil constituted by society. For Victor Goldschmidt, one should not insist too much on the opposition between the contract of the Discourse and that of the Social Contract because in both the inequality is present .

Victor Goldschmidt notes in Anthropologie et Politique ( p. 779-780) that Rousseau "discovered social constraint, the [...] social relation [...], the autonomous life and development of structures [...] , their independence with regard to individuals and, correlatively, the web of dependence of these same individuals with regard to these structures” .

Self-love and pity or the end of the naturally good man

Rousseau repeatedly repeats that the idea that man is naturally good and that society corrupts him dominates his thought. The question that then comes to mind is: how can evil arise in a society of good men? The adjective "good" does not mean that originally men are naturally virtuous and beneficent but, according to John Scott, that in man "there would originally exist a balance between the needs and passions and the capacity to satisfy them” , and it would be this balance which would make man “good for himself and not dependent on others” , because precisely it is “dependence on others which makes men bad” .

Rousseau argues that to enable the preservation of the species, creatures are endowed with two instincts, self-love and pity. Self-love enables them to satisfy their biological needs, while pity drives them to care for others. Note that, if pity is in the Second discourse an independent instinct, in Émile and in the Essai sur l'origine des langues , it is considered only as an extension of self-love seen as the origin of all passions .

The fall, or evil, is introduced in man with the appearance of self-esteem, an appearance moreover linked to sexual competition to attract a partner. Rousseau writes in note 15 of the Discourse on the Origin of Inequalities :

“Self-love is a natural sentiment which leads every animal to watch over its own preservation and which, directed in man by reason and modified by pity, produces humanity and virtue. Self-esteem is only a relative, factitious feeling, born in society, which leads each individual to make more of himself than of any other, which inspires in men all the harm they do to each other. and who is the true source of honour . »

In summary, self-esteem drives human beings to compare themselves, to seek to be superior to others, which leads to conflict. However, if we look at the way in which he treats the question starting from Émile , it is possible to note that self-love is both the instrument of man's fall and of redemption . Indeed, in this book, self-esteem is the form that self-love takes in a social environment. If, in Rousseau, self-love is always seen as dangerous, it is possible to contain this evil thanks to education and thanks to a good social organization, as we find them expounded respectively in Émile and the Social Contract .

Even if self-esteem has its source in sexual competition, it reveals its full potential for danger only when it is combined with the economic interdependence that develops when individuals live in society. Indeed, in this case, human beings will seek both material goods and recognition, which leads them to maintain social relations marked by the subordination of some and by the desire to achieve one's ends whatever the circumstances. means employed. So that both the freedom of human beings and their self-esteem are threatened .

Passions, reason and perfectibility

Unlike Aristotle, but like Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, for Rousseau, reason is subordinated to the passions and in particular to self-love . Moreover, passions and reason evolve, have their own dynamics. Initially, in the state of nature, the human being has only few passions and reason. Rousseau notes, concerning men in a state of nature (which he calls savages) that they “are not evil precisely because they do not know what it is to be good; for it is neither the development of enlightenment nor the curb of the Law, but the calm of the passions and the ignorance of vice which prevents them from doing wrong” . The dynamics of the passions and of reason which leads to their evolution is explained by Rousseau in the following passage:

“Whatever the Moralists say, human understanding owes much to the Passions, which, by common consent, owe it much also: It is by their activity that our reason is perfected; We seek to know only because we desire to enjoy, and it is not possible to conceive why someone who has neither desires nor fears would take the trouble to reason. The Passions, in their turn, derive their origin from our needs, and their progress from our knowledge; for one cannot desire or fear things, except on the ideas that one can have of them, or by the simple impulse of Nature; and the savage man, deprived of all sorts of light, experiences only the Passions of this latter kind . »

For Rousseau, the dominant trait of man is not reason but perfectibility . Speaking of the difference between human beings and animals, Rousseau writes “There is another very specific quality which distinguishes them, and on which there can be no dispute, it is the faculty of perfecting oneself; faculty which, with the aid of circumstances, successively develops all the others, and resides among us both in the species and in the individual, whereas an animal is, after a few months, what it will be his whole life". If Rousseau is one of the first, even the first, to use the word perfectibility, for him, the word does not only have a positive aspect. On the contrary, it most often has a negative aspect. Indeed, for the citizen of Geneva, perfectibility is only the ability to change, an ability that most often leads to corruption .

Virtue and conscience

According to Georges Armstrong Kelly, "Rousseau refers to 'wisdom' as the seat of virtue, the consciousness which does not create light, but rather which activates man's sense of cosmic proportions" . For Rousseau, moral truth is the unifying element of all reality. Knowledges are only false lights, mere projections of self-love, if they are not rooted, as with him, in an inner certainty.. Otherwise, reason can be corrupted by the passions and turn into false reasoning that flatters self-esteem. If reason can provide access to the truth, only conscience, which imposes the love of justice and morality in an almost aesthetic way, can make it loved. The problem, for him, is that conscience based on a rational appreciation of an order laid down by a benevolent God is a rare thing in a world dominated by self-love .

Political philosophy

Rousseau mainly exposes his political philosophy in the Discourse on the origin and the foundations of inequality among men , the Discourse on political economy , On the social contract as well as in the Considerations on the government of Poland . Rousseau's political philosophy is situated in the so-called contractualist perspective of British philosophers of the 17th and 18th centuries. Moreover, his Discourse on Inequality is sometimes considered as a dialogue with the work of Thomas Hobbes. For Christopher Bertram, the heart of Rousseau's political doctrine lies in the assertion“that a State can be legitimate only if it is guided by the general will of its fellow citizens” .

Some Important Words from Rousseau's Political Philosophy

| Terms | Definitions and/or meaning of terms for Rousseau |

|---|---|

| love of country | Sweet and lively sentiment which joins the strength of self-love to all the beauty of virtue. Effective in helping people conform to the general will . |

| Body politic | Is also a moral being who has a will; and this general will always tends to the preservation and well-being of the whole and of each part . Its establishment is carried out thanks to a true contract by which the two parts are obliged to observe the laws. |

| Corruption of people and leaders | It intervenes when particular interests come together against the general interest; when public vices have more force to enervate the laws than the laws to repress vices. Then the voice of duty no longer speaks in hearts . |

| Government | Is not master of the law but is its guarantor and has a thousand ways to make it loved . |

| Legislator | Its first duty is to conform to the general will . |

| Law | Synonym of public reason. Opposes the private reason which aims at particular interests . |

| Sovereignty | It is the supreme authority, from which proceeds legislative law . With Rousseau, sovereignty, that is to say “absolute and perpetual power” passes from the monarch to the people . |

| Virtue | Science of simple souls. Its principles are engraved in all hearts. To learn its laws, it suffices to return to oneself and to listen to the voice of conscience in the silence of the passions . Virtue also consists in the conformity of the particular will to the general will . |

| General will | It tends to the conservation of the body politic and its parts; it always tends towards the common good. It is the voice of the people when they do not allow themselves to be seduced by special interests . |

General will

Will and generality

The general will is the key concept of Rousseau's political philosophy. But this expression is made up of two terms—will and generality—whose meaning should be clarified, if we want to understand the thinking of the citizen of Geneva properly.

The will, with Rousseau, as with all the “voluntarists” coming after Augustine of Hippo's book On Free Will , must be free to have moral value. Freedom is first understood as non-submission to the authority of other men, as is the case with paternal power or the power of the strongest . However, Rousseau doubts that the will alone can lead men to morality. According to him, men need either great legislators like Moses, Numa Pompilius (Rome) or Lycurgus (Sparta), or educators so that the will is oriented towards the good while remaining free .

For Rousseau, to say that the will is general means that it is situated somewhere between the particular and the universal as with Pascal, Malebranche, Fénelon or Bayle. According to Patrick Riley, this vision of the “general” would be “quite distinctly French” . On this point Rousseau opposes Diderot who, in the article "Natural Law" of the Encyclopédie , develops the idea that there exists both a general will of the human race and a universal morality, which leads him to think of the general in universal terms. Rousseau, whose models are Rome, Sparta or even Geneva, insists, on the contrary, on the importance of national particularisms .

Rousseau is not the first to join the two words "general" and "will" and to use the expression "general will" : before him, Arnauld, Pascal, Malebranche, Fénelon, Bayle or Leibniz had also used it . But they used it to designate the general will of God, whereas for Rousseau it is the general will of the citizens. In short, the philosopher secularizes and democratizes expression.

Interpretations of the notion of general will

For Christopher Bertram, the general will in Rousseau is an ambiguous notion that can be interpreted in two ways: in a democratic conception, it is what the citizens have decided; in a conception more oriented towards transcendence, it is the embodiment of the general interest of citizens obtained by disregarding particular interests . The first interpretation is based mainly on chapter 3 of book 2 of Du contrat social where Rousseau insists on the procedures of deliberation to achieve the general interest .

It is possible to unify these two views by assuming that, for Rousseau, under the right conditions and with the right procedures, citizens will ensure that the general will resulting from deliberation corresponds to the transcendent general will . But, for the citizen of Geneva, this identity is not assured. He writes about this:

“It follows from what precedes that the general will is always right and always tends to public utility: but it does not follow that the deliberations of the people always have the same correctness. We always want what is good, but we do not always see it ( On the social contract book II, chapter III, p. 56). »

Believing that the quality of the deliberation of the citizens, once they are sufficiently informed, is endangered by the effects of rhetoric and the simple communication of the citizens among themselves, he asserts that the Athenian democracy was in reality "an aristocracy very tyrannical, governed by “scholars” and “orators” .

Law and law in Rousseau

Law and natural law

Rousseau, in the Discourse on Inequality , argues that natural law can be understood in two very different ways. For the Roman jurisconsults, the natural law expresses "the expression of general relations established by nature between all living beings, for their common preservation" . For modern naturalists, the law is "a rule prescribed for a moral being, that is to say, intelligent, free, and considered in its relations with other beings" , it is natural in the sense that it pursues the ends natural aspects of man on which, according to Rousseau, the philosophers of his time hardly agreed. It follows that if there were a natural law, it would have to meet the two previous definitions, which he considers impossible. For if men in a state of nature acted spontaneously with a view to the common utility, this is no longer the case with modern man. So that, according to Gourevitch, when Rousseau uses the term "natural law" , he is not referring to his own views but to those of modern naturalists . When he sets out his views, Rousseau prefers to speak of “natural law” , for at least two reasons: the law is generally understood as the expression of a command from a superior to an inferior, not the right; furthermore, the law may be applied differently depending on the circumstances .

The problem for Rousseau is that while self-love and pity cause human beings to follow natural law, because of the development of economic interdependence between men, self-love becomes self-love and the law of human nature ceases to ensure respect for natural law. This observation leads Rousseau to state his “central thesis [according to which] once men have become irreversibly dependent on each other, spontaneous – ‘natural’ – conformity to natural law cannot be restored on a world scale” .

Political law and justice

Rousseau differentiates natural law from political law. The latter refers to the principles or laws of what he often calls “well-constituted states” . Political law aims, within the framework of a State or a body politic, to positively establish a society that allows people to live well. It is not a question of returning to the state of nature but of being able to lead a good life. For this, political law, aided by instrumental reason, must allow a return to a certain form of justice. This leads Rousseau to distinguish three types of justice: "divine justice" , "universal justice" and "human justice".. The first comes from God; the second refers to Diderot who, in the article “Droit naturelle” of the Encyclopédie (IC, 2), sees law and justice as a pure act of reason; the third is that of Rousseau. For him, the idea of justice refers to a body politic and does not extend to the whole world . Rousseau notes in this regard:

“What is good and conforming to order is such by the nature of things and independently of human conventions. All justice comes from God, he alone is the source; but if we knew how to receive it from so high, we would need neither government nor laws. Doubtless there is a universal justice emanating from reason alone; but this justice, to be admitted between us, must be reciprocal. Considering things humanly, for lack of natural sanction the laws of justice are vain among men; they only do the good of the wicked and the evil of the just, when the latter observes them with everyone and no one observes them with him. Conventions and laws are therefore needed to unite rights with duties and bring justice back to its object . »

Body politic and citizenship

Political society, civil society and political law

According to Rousseau, political society is not natural and for him, man is not a political animal as in Aristotle. The body politic which arises from the convention and consent of the members allows the aggregation of resources as well as the pooling of the forces and resources of the members of society. To designate this political body, Rousseau also uses the terms well-constituted society, “people” , Republic, “State when it is passive, Sovereign when it is active, power by comparing it to its fellows” . The end or purpose of a body politic is to provide a means of transforming the unequal social contract of civil society into“a form of association which defends and protects with all common force the person and property of each partner, and by which each uniting with all nevertheless obeys only himself and remains as free as before » .

The man/citizen distinction

Natural law is good for man, political law for the citizen. The citizen through political law engages in a project aimed at improving society. Participating in a true social contract provokes for Rousseau a change of perspective which distinguishes the man from the citizen. Indeed, the citizen must learn to consider himself as part of a whole, to listen to the voice of duty, to “consult his reason before listening to his inclinations” . To unite the citizens, so that they form a whole, Rousseau considers that having the same habits, the same beliefs and practices is a help. Patriotism is also a means of uniting citizens and facilitating their acceptance of the general will. Rousseau writes about this:“Love of country is the most effective; for as I have already said, every man is virtuous when his particular will is in conformity in everything with the general will, and we willingly want what the people we love want” . We know that, for Rousseau, men are driven by two principles: self-love and pity. In the citizen, pity must give way to reciprocity. “The commitments that bind us to the social body are only binding because they are mutual” .

Equality, justice, utility and the body politic

In Rousseau, the notion of justice is linked to reciprocity. The problem is that for there to be reciprocity, there must be equality. But since the end of the state of nature, natural freedom and equality have vanished. They must therefore be reconstituted in a conventional manner. In his project for the reconstitution of equality and freedom, Rousseau does not consider equality as an end in itself, but as the means of securing the political freedom which can only exist between equals. If Rousseau is not opposed to inequalities resulting from the efforts of human beings but to inequalities not justified by nature, he nevertheless considers that equality is always threatened and he sees its inclusion in the long term as a challenge that men must take up. permanently. For him, political rights are based on men as they are with their self-esteem, their interests, their views of the common good, which leads him to a relatively pragmatic approach. He writes in The Social Contract :

“I will always try to combine, in this research, what the law allows with what interest prescribes, so that justice and utility are not divided . »

The sovereignty of the people

In Rousseau, the people understood in the political sense of all citizens is sovereign, that means that it is he who promulgates or ratifies the laws, it is from him that the general will comes. If he is sovereign, however, he does not govern and has no vocation to govern .

It is therefore a question of determining how the sovereignty of the people can be exercised. There are two possible solutions: direct democracy or representative democracy. Rousseau is not very enthusiastic for representative democracy and prefers a form of direct democracy modeled on the ancient model. To confine oneself to voting is, according to him, to have a sovereignty which is only intermittent. He thus makes fun of the electoral system then in force in England, by affirming that the people there are free only on the day of the elections, and slaves as soon as their representatives are elected . His criticism of the idea of representation of the will is therefore severe:

“sovereignty cannot be represented, for the same reason that it cannot be alienated; it consists essentially in the general will, and the will cannot be represented: it is the same, or it is different; there is no middle ground. The people's deputies are therefore not and cannot be its representatives, they are only its commissioners; they cannot conclude anything definitively. »

Rousseau goes on: “any law that the people in person have not ratified is void; it is not a law” . Christopher Bertram believes, however, that while the interpretation set out above is the most widespread, it is not clear that it is correct and that Rousseau really rejects any form of representation as he suggests .

Even if Rousseau has a vision of sovereignty different from that of Hobbes, just like in the latter, the citizens by associating lose all their natural rights, in particular that of control of sovereign power .

Government

Government and sovereignty

The sovereign, the people according to Rousseau, promulgates the laws which are the expression of the general will. The government, by contrast, is a more limited body of people who administer the state within the framework of the laws. It is authorized to promulgate decrees of application of the laws in the cases where it is necessary .