Jean-François Champollion

Jean-François Champollion, known as Champollion the Younger (Figeac, Lot department, December 23, 1790-Paris, March 4, 1832), was a French historian (linguist and Egyptologist), considered the father of Egyptology for having managed to decipher hieroglyphic writing thanks mainly to the study of the Rosetta stone. He received his doctorate in Ancient History from the University of Grenoble. A child prodigy in philology, he gave his first public paper on the decipherment of Demotic in 1806, and as a young man held many positions of honor in scientific circles and was fluent in Coptic and Arabic.

In the early 19th century, French culture experienced a period of "Egyptomania", brought about by by Napoleon's discoveries in Egypt during his campaign there (1798-1801), which also brought to light the trilingual Rosetta Stone. Scholars debated the age of Egyptian civilization and the function and nature of hieroglyphic writing, what language it recorded, if any, and the degree to which the signs were phonetic (representing speech sounds) or ideographic (recording semantic concepts directly). Many thought that the script was only used for sacred and ritual functions, and as such was unlikely to be decipherable since it was tied to esoteric and philosophical ideas, and did not record historical information. The importance of Champollion's decipherment was that he showed these assumptions to be incorrect and made it possible to begin to recover many types of information recorded by the ancient Egyptians.

Champollion lived through a period of political turmoil in France that continually threatened to disrupt his research in various ways. During the Napoleonic Wars, he was able to avoid conscription, but his Napoleonic loyalties meant that he was considered a suspect by the later royalist regime. His own actions, sometimes brazen and reckless, did not help his case. His relationships with important political and scientific figures of the time, such as Joseph Fourier and Silvestre de Sacy, helped him, although at times he lived in exile from the scientific community.

In 1820, Champollion embarked in earnest on the project of deciphering the hieroglyphic script, which soon eclipsed the achievements of the British scholar Thomas Young, who had made the first advances in decipherment before 1819. In 1822, Champollion published his first advance in the decipherment of Rosetta, hieroglyphics, which show that the Egyptian writing system was a combination of phonetic and ideographic signs, the first script of its kind discovered. In 1824, he published a Précisen which detailed a decipherment of the hieroglyphic script demonstrating the values of its phonetic and ideographic signs. In 1829, he traveled to Egypt, where he was able to read many hieroglyphic texts that had never been studied before, and took home a large number of new drawings of hieroglyphic inscriptions. Back home he was given a professorship in Egyptology, but he gave only a few lectures before his health, ruined by the difficulties of the Egyptian journey, compelled him to give up teaching. He died in Paris in 1832, at the age of 41. His Ancient Egyptian Grammar was published posthumously.

During his lifetime, as well as long after his death, there were intense discussions among Egyptologists about the merits of his decipherment. Some criticized him for not giving sufficient credence to Young's early discoveries, accusing him of plagiarism, and others long questioned the accuracy of his decipherments. But later findings and confirmations of his readings by scholars who relied on his results gradually led to general acceptance of his work. Although some still argue that he should have recognized Young's contributions, his decipherment is now universally accepted and has been the basis for all subsequent developments in the field. Consequently, he is considered the Founder and Father of Egyptology. [1]

Biography

Jean-François Champollion was born on December 23, 1790 in Figeac, a town in the Midi-Pyrénées region, and was baptized that same day in the Church of Our Lady of Puy. His father, Jacques Champollion, came from from Valbonnais, a small town near Grenoble, and had dedicated himself to peddling books until he moved to Figeac and managed to open his own bookshop on the market square. There he met Jeanne-Françoise Gualieu, a girl from a good but illiterate family, whom he married in 1773 when they were both thirty years old. Jean-François was the last of his seven children and had three brothers: Jacques-Joseph, Guillaume, stillborn, and Jean-Baptiste, who died when he was two; as well as three sisters: Thérèse, Pétronille and Marie-Jeanne.

Born in the middle of the French Revolution, he did not receive any formal education until he was seven years old since the schools, almost all run by religious orders, had been closed. With his mother frequently ill and his father absent due to his business trips, Jean-François was in the care of his brother Jacques-Joseph, twelve years older than him, and his three older sisters. He tried to learn to read, write and draw on his own, until Jacques-Joseph, self-taught and interested in ancient history, began to give him classes, but a few months later, in July 1798, he had to move to Grenoble, where his father I had gotten him a job. In November he entered the primary school, which had reopened again, but although very intelligent, he could not adapt to the school demands, he was weak in spelling and had an aversion to some subjects, especially mathematics, so at the suggestion of his His brother was found a private teacher. The chosen one was Dom Calmels, a Benedictine with whom he made great progress in the study of Latin and Greek, although he continued to maintain an erratic attitude and, when Calmels judged that he could teach him nothing more, he suggested to Jacques-Joseph that in order to develop his talent he would have more opportunities at Grenoble. Champollion arrived in Grenoble in March 1801, just turned ten, and would in time come to regard the city as his true home ahead even of Figeac.

Jacques-Joseph by then had changed his surname to Champollion-Figeac and Jean-François was also sometimes called that, but he preferred to differentiate himself as "Champollion le Jeune" (Champollion the Younger). His sister first assigned him a private teacher and then taught him himself until, in November 1802, she enrolled him in the private school of Abbe Dussert, one of the best and most expensive in Grenoble. There he only studied languages (for the other subjects he attended the central school) and by the end of his first year he had made so much progress in Latin and Greek that he also began to study Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac and Chaldean.

At the age of twelve he met Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier, who had been appointed prefect of the Isère department in early 1802, shortly after he had returned from Napoleon's expedition to Egypt. Fourier, who had worked at the Egyptian Institute in Cairo and was commissioned to write the preface to the monumental Description of Egypt (Description de l'Égypte), he met Champollion on one of his inspection visits to the schools and, impressed by his interest in Egypt, invited him to the prefecture to see his collection of antiquities. After contemplating the hitherto incomprehensible hieroglyphics, he left there, not only determined to try to decipher them, but also convinced that he would succeed.

The Lyceum

In 1804 the Lycée de Grenoble was inaugurated and, at the beginning of the same year, Champollion passed the entrance exam and obtained a scholarship that covered three-quarters of the expenses. The Lycées had been established by a Napoleonic law in 1802, forty-five were created throughout France and were intended to be elite schools, with a completely uniform study program and governed by a military discipline under a regime of boarding school to which Champollion could not adjust in the two and a half years he spent there. He was grateful to his brother, who paid for the expenses not covered by his scholarship, but he was always short of money compared to his peers, most of whom came from wealthy families, and he was also forbidden to pursue his own studies of oriental languages, the only ones which really interested him even in his free hours. He privately learned Coptic, Italian, English and German. In 1807 students at the lycée staged a revolt against the strict study rules, and Jacques-Joseph finally allowed his sister to live in his house, under his care, and only come to school when he considered it necessary.

Paris

In August of that same year he finished his studies in Grenoble, and Champollion moved to the capital, Paris, in order to continue his studies on ancient languages. His interest in the study of Egyptian hieroglyphs began then, and he was not the only one: throughout Europe, intellectuals, locked in libraries, and in the narrowest of secrecy, each one worked on their own to be the first to solve the hieroglyphics riddle. Pressured by the meager but steady advances of some of these scholars, Jean-François felt time slipping away; Only his brother, with great gifts for ancient languages and who had already made a failed attempt to decipher the Rosetta Stone, understood his brother's desire. He again supported him financially despite the fact that he had to support a growing family.

Do not be discouraged by the Egyptian text; this is the time to apply Horatio's precept: a letter will take you to a word, a word to a phrase and a phrase to the rest, as everything is more or less contained in a simple letter. Keep working until I can see your work for yourself.Champollion

Champollion believed that in order to understand Egyptian texts, it was necessary to know, translate, and interpret Coptic without error, an ability lacking in all those scholars who aspired to decipher hieroglyphics. His study scheme predicted that through Coptic he would understand the inscriptions in Demotic (an abbreviated form of hieratic script) and with the help of the Egyptian language, he would be able to decipher the hieroglyphic script. For this he studied Coptic at the College of France, at the School of Oriental Languages and at the National Library in Paris. He also learned liturgical Coptic from an Egyptian priest. As a teenager, he managed to compile a 2,000-word Coptic dictionary. Silvestre de Saçy, an expert in hieroglyphics, was one of his new teachers. Unfortunately, and due to the management of Napoleon, who did not cease in his efforts to orchestrate constant military campaigns that demoralized the entire nation, and given the scarcity of food and high inflation, there was no time for study, and whoever wanted to To survive in such circumstances, he must have been extremely lucky to have a steady, paid job, something Jean-François lacked. He lived in eternal fear of being drafted into the army, healthy young people were scarce; his health was very deteriorated, he was sunk in a deep depression, terribly thin and practically dressed in rags. The one who would be one of the fathers of Egyptology, and the man who deciphered the Rosetta Stone, was little more than a beggar.

At this time, at just sixteen years old, he writes to his brother Jacques-Joseph:

I completely consecrate myself to the copto. I want to know the Egyptian as much as my own mother tongue, because in this language will be based my great work on the Egyptian papyrus.Champollion, 1807

University of Grenoble

His luck would change again in 1809 when, at just 18 years of age, he published his Geography of Egypt, the first part of what was intended to be a larger work. Thanks to this publication he obtained a position as Professor of Ancient History at the newly founded University of Grenoble. Jacques-Joseph obtained that same year, and at the same university, a position as Professor of Greek Literature. Both brothers earned doctorates. Despite having a stable and decent job, they continued to have problems, not just money, but also personal and political. In 1813, while Jean-François received a miserably low salary, forcing him to humiliate himself by teaching former classmates at the Lycée whom he had considered inferior to him at the time, and the family of Rosine Blanc (wealthy owners of a of gloves), the girl he was courting, refused to allow them to marry, Jacques-Joseph was having problems with his wife and family.

Both brothers had an unhealthy and worrying interest in politics; they professed to be openly Bonapartists, were painfully frank and candid, and frequently riled up anyone who tried to exert any authority over them. They did not know how to use diplomacy and they made enemies with great assiduity. It was impossible for them to go unnoticed wherever they went. The brothers' greatest concern lay in the difficulty of obtaining copies of the hieroglyphics, something that would never have happened in Paris.

In 1814 the Champollion brothers were still penniless, Jean-François more so than his brother, while across the Channel in London, Dr. Thomas Young, polymath, scientist, astronomer, musician, physician and Professor of Natural Philosophy at the Royal Institute was short of time to devote himself to the Rosetta stone in the way that Champollion did. In the time that he managed to do it, he managed to correctly identify at least forty signs. Champollion worked on and corrected the list that Young published. For a long time they corresponded sporadically, had a rather superfluous friendship that dwindled over time, and at times came to consider themselves bitter enemies and rivals.

When Napoleon abdicated in 1814 and left France for the Isle of Elba, Louis XVIII ascended the throne of France. Napoleon's party prevented the attack of the Austrian army, which had declared war on France a year earlier. The Champollion brothers, despite having criticized Napoleon's regime at some point, remained faithful Bonapartists. One of his flaws was that both Jacques-Joseph, who considered Bonaparte his hero, and Jean-François, failed to keep their political leanings secret. They began to harshly criticize the monarchy.

In March 1815 Napoleon returned from his exile on Elba to France. On his way to Paris he stopped for a whole day in Grenoble where he met the Champollion brothers. Such was the impression it made on Jacques-Joseph that he made the decision to leave his family and follow Napoleon north. Sponsored by the visit of his hero Jean-François, he published an article that turned out to be a powder keg against him. In his writing you could read:

Napoleon is our legitimate prince.Champollion, 1815

With this quote he made it clear what his loyalties were in the political sphere. He couldn't have chosen a more inopportune moment. Napoleon embarked on the difficult task of winning a war that he had lost beforehand; Waterloo, and he again went into exile. This time to the distant island of Santa Elena. Meanwhile Grenoble, which remained faithful to the dictator, ended up being bombarded jointly by the armies of Austria and Sardinia. Jean-François, worried about his older sister who was still in Paris, wrote to her these lines:

Especially save yourself... I don't have a wife or a son.Champollion, 1815

Banishment

In 1816 they were officially expelled from the University and sentenced to exile in Figeac, the place where they were born, sharing the family home with their elderly and alcoholic father and two of their three sisters, the unmarried Thérèse and Marie-Jeanne. In 1817 the younger Champollion's sentence was lifted so that he could return to Grenoble where, in December 1818, he was finally able to marry Rosine.

Towards the end of 1821 Champollion made real and important progress in his studies of hieroglyphic signs. First, he managed to show that hieratic writing was not, but a simpler and abbreviated form of hieroglyphic writing. On his part, the demotic script was a later and still more simplified version of the hieratic. In short, the ancient Egyptians had used three different scripts to write the same words. That same year he managed to classify and compose a table of 300 hieroglyphic, hieratic and demotic signs, which allowed him to make transcriptions between the three.

Despite the extraordinary progress of his jobs, his personal life was not going well at all. He was sick again, depressed, jobless, and back in Paris. He shared a house on rue Mazarine, near the Institut de France, where his brother had found a job.

Thanks to the comparisons of various texts written with hieroglyphic signs, he realized that there were homophone letters; they might sound the same, but they were written in two different ways. Like the T in Cleopatra and Ptolemy: they sounded the same, but they were spelled differently for each of their names. He was soon able to study the inscriptions from the Karnak temple, located in Thebes, which allowed him to reconstruct Alexander's name. It took him a short time to reconstruct a phonetic alphabet that could be applied to all the Greco-Roman names that were written in Egyptian. The most difficult thing was missing: deciphering the real names in Egyptian.

On September 14, 1822, the door of Jacques-Joseph's office was flung open and an emotional Jean-François, who had been working at home, as usual, ran in shouting Je tiens l& #39;affaire! (Got it!) and fell fainting to the ground. For a moment Jacques-Joseph believed that his sister was dead. Nothing could be further from the truth, the young Champollion had received texts fifteen hundred years older than those of the Rosetta Stone, which contained real names. To his astonishment, he was able to recognize names of Egyptian kings, which had previously been found in Greco-Roman works.

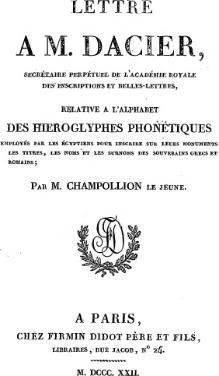

Barely thirteen days later, on September 27, his discovery was formally presented to the Academy of Inscriptions in Paris by means of a letter. Letter to M. Dacier regarding the hieroglyphic phonetic alphabet used by the Egyptians (Bon-Joseph Dacier was the secretary of the Academy at the time). The letter was translated and published in several languages and praise and criticism began. Some did not believe him; others, like Thomas Young, accused him of stealing the ideas of others. Champollion did not give up; Thanks to visits to the Museum of Turin, which housed many hieroglyphic texts, in 1824 he had perfected his system and was able to publish Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens (Summary of the hieroglyphic system of ancient Egyptians) In this work he explained the complicated nature of hieroglyphics:

The hieroglyphical writing is a complex system, a writing that is at a figurative, symbolic and phonetic time in the same text, in the same sentence and, should say, almost in the same word.Champollion, 1822

Louvre Museum

In 1826 he achieved recognition for a lifetime's work. He was appointed curator of the Egyptian collection at the Louvre museum. He collected objects to mount exhibitions, he organized the exhibition itself, and above all he had to face all those colleagues who he did not believe deserved the respect he had earned with his work. He managed to have the objects displayed in a sensible and chronological way, although he was not allowed to decorate the rooms in a truly Egyptian style.

Two years later his biggest dream came true; to visit Egypt. He was a member of a Franco-Tuscan mission that also included the Italian Egyptologist Ippolito Roselini, as well as twelve artists, draughtsmen, and architects. It was the first and only time that he was able to set foot on Egyptian land. They disembarked in Alexandria on August 18, 1828, first going to Cairo, where they saw the pyramids for the first time. On December 4 they arrived in Aswan, in the south of the country. They then went into Nubia so they could visit the rock-cut Ramesside temples at Abu Simbel.

A fragment of the letter he writes to his brother shows his first impressions:

Although it was only for the great temple of Abu Simbel, it would be worth the trip to Nubia: it is a wonder that even in Thebes would consider something beautiful. The work that cost this excavation defies the imagination. The facade is decorated with four colossal headquarters statues, not less than eighteen meters high. The four, works of superb craftsmanship, represent Ramses the Great: their faces are portraits and keep a perfect resemblance to the images of this king in Menfis, in Thebes and anywhere else. It is also the entrance; the interior is totally worth visiting, but doing so is an arduous task. On our arrival the sand and the clouds in charge of moving it had blocked the entrance. We made it clear so that they opened a small gap and then took all the precautions we could against the sand that fell, which in Egypt, as well as in Nubia, threatens to bury everything. I was almost completely naked; I was only wearing my Arab shirt and cotton panties, and I moved on to the stomach to the small threshold of a door, which, if it had been clear, would have measured at least seven and a half meters high. I thought I was moving into the mouth of an oven and, sliding into the interior of the temple, I found myself in an atmosphere at 52 °C of temperature... After spending two and a half hours admiring everything and seeing all the reliefs, the need to breathe a little pure air was imposed and it was necessary to return to the entrance of the oven.Champollion, 1828

Death

After spending 18 months working in the field, enjoying the authentic life of an archaeologist, his health began to suffer. He returned exhausted to France to complete his greatest and most ambitious work, his Grammaire égyptienne ( Egyptian Grammar ). In March 1831 he was appointed Professor of Archeology at the College de France. He would not enjoy his deserved position for long. He died on March 4 of the following year. He was 41 years old, he suffered from diabetes, he suffered from consumption, gout, paralysis, he had liver and kidney disease. A heart attack ended his life.

Jacques-Joseph was devastated by the death of his younger brother. In 1832, as a posthumous tribute to his brother, he managed to finish and edit the last work of Jean-François Champollion, the Egyptian Grammar, whose elaboration had made him leave the country of the pyramids with which I had dreamed so much.

Career

- Liceo de Grenoble

- Study of the Semitic-Camitic Languages in Paris

- Associate Professor of History at the University of Grenoble

- Conservative of the Egyptian Museum of the Louvre

- Professor of Egyptian Archaeology at Collège de France

Honors

Champollion Museums

- At home in Figeac

- Museum Champollion Vif, in Isère, old property of his Egyptian brother

Busts in public places

- Revealed its restored bust, from the sculptor Erminio Blotta, on Boulevard Oroño, Rosario (Argentina).

Moon Crater

- The lunar crater Champollion bears this name in his honor.

Asteroid

- The asteroid (3414) Champollion bears this name in his honor.

Work

- 1822, Lettre à M. Dacier relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques.

- 1824, Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens.

- 1826, Lettres à M. le Duc de Blacas d'Aulps.

- 1827, Notice descriptive des monuments égyptiens du Musée Charles X.

- 1828, Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens ou Recherches sur les élémens premieres de cette écriture sacrée, sur leurs diverses combinaisons, et sur les rapports de ce système avec les autres méthodes graphiques égyptiennes.

- 1828-29, Lettres écrites d'Égypte et de Nubie [3]

- 1836, Grammaire égyptienne (Egyptian grammar, posthumous work)

- 1841, Dictionnaire égyptien en écriture hiéroglyphique (Egyptian Dictionary of Hieroglytic Writing)

Almost all of them edited after his death.

Contenido relacionado

French Academy of Sciences

History of science

Hildegard of Bingen

Grain (unit of mass)

Averroes