Jaws (film)

Shark (original title: Jaws; in Spanish Fauces or Jaws) is a 1975 American horror, thriller, and adventure film directed by Steven Spielberg and based on Peter Benchley's novel of the same name. In the story, a man-eating great white shark attacks beachgoers on Amity Island, prompting the local police chief to hunt down the shark alongside a marine biologist and a professional shark hunter. Actor Roy Scheider plays police chief Martin Brody, Richard Dreyfuss plays oceanographer Matt Hooper, Robert Shaw plays shark hunter Quint, Murray Hamilton plays Amity Island mayor and Lorraine Gary plays Brody's wife Ellen. The script is credited to both Benchley himself, who did initial drafts, and actor/screenwriter Carl Gottlieb, who rewrote it during filming.

Most of the film was filmed on the island of Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts. It was a bumpy shoot that exceeded the initial budget and schedule. There were problems with the mechanical replica of the shark and the director Spielberg was forced in many of the scenes to suggest the presence of the shark instead of showing it, supported by a minimalist and disturbing musical theme created by the composer John Williams that indicates the imminent appearances of the predator. Many, including the film's director himself, have compared this suggestive approach to that of director Alfred Hitchcock's classic thrillers. Universal Pictures released the film in an unusually high number of theaters for the time, more than 450. in North America, and accompanied it by a massive and effective advertising campaign with heavy emphasis on television commercials and associated merchandise.

Considered one of the best films in the history of cinema, Jaws is the prototype of the summer blockbuster and its premiere is remembered as a true milestone of the seventh art. It was the highest-grossing production until the release of Star Wars in 1977. It received numerous awards for its soundtrack and editing, and along with Star Wars, Jaws was the point of departure from the modern Hollywood business system, which revolves around action or adventure films based on simple premises, which are released in summer surrounded by large advertising campaigns and in many movie theaters to try to ensure their success among the public. Jaws was followed by three sequels, none involving Spielberg or Benchley, and numerous films that imitated it. In 2001, the film was selected by the United States Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Plot

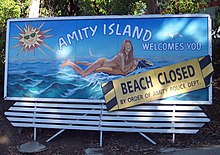

A girl named Chrissie leaves an all-night party on a beach in the town of Amity Island to go skinny dipping in the sea. After swimming to a buoy, she is attacked by an unseen force, dragged screaming through the water, and finally disappears from the surface.

The next morning she is reported missing and soon after the local police chief, Martin Brody, finds her mutilated remains on a beach. The coroner reveals that the girl was attacked by a shark and therefore Brody suggests closing the beaches to bathers, but his proposal is rejected by the mayor of the town, Larry Vaughn, who fears that the news will ruin the imminent summer season. main source of income for the tourist town. Consequently, the coroner decides to attribute Chrissie's death to a boating accident, an explanation that Brody reluctantly accepts. Shortly after the shark attacks again on the beach and kills a boy named Alex. His mother offers a reward to whoever kills the shark, sending the local fishermen into a frenzy and attracting the attention of professional shark hunter Quint. Matt Hooper, a marine biologist who has just arrived in town at the request of the police chief, examines Chrissie's remains and determines that she was, without a doubt, killed by a shark.

A fisherman catches a massive tiger shark, leading Amity Islanders to believe their problem has been solved. However, Hooper examines the size of the animal and doesn't believe it was responsible for the deaths. Despite this, Mayor Vaughan is opposed to making the biologist's opinion public. That same night Hooper shows up at Brody's house for dinner and talks to him and his wife Ellen about his experiences with sharks and his fascination with them. Hooper still doesn't believe the man-eater has been hunted, so he and Brody go to examine the stomach contents of the captured shark and find that it contains no human remains. The two set out to sea that same night to try to find the shark, but instead they find the sinking boat of local fisherman Ben Gardner. Hooper dives into the water and discovers a huge shark tooth on the hull just before he stumbles upon Gardner's mutilated corpse, which scares him into knocking out the shark tooth. With no physical evidence, Brody and Hooper fail to convince Mayor Vaughan, who refuses to close the beaches.

Tourists begin to arrive en masse on the 4th of July, but a childish prank creates a panic on the beach. At the same time, the killer shark enters a nearby lagoon and kills a man. Brody's son witnesses the attack and goes into shock. The policeman manages to convince the mayor to hire Quint's services and go in search of and capture the animal. The shark hunter reluctantly agrees to let Hooper join the hunting party on his boat with Brody, and in order to find and kill the elusive shark, the three set sail on Quint's small boat, the Orca i>.

Out at sea, Brody begins casting bait while Quint prepares the fishing tackle he'll need to catch the animal. At that moment, a great white shark rises out of the water astern, impressing Brody, who tells Quint, "You'll need a bigger boat." The shark begins to circle the small boat while Hooper takes pictures for the investigation. Quint manages to harpoon the animal and attach a floating barrel to it to keep it located and close to the surface, but the powerful shark submerges it and disappears.

The three retire to the ship's cabin for dinner, and Quint takes the opportunity to tell his companions about his ordeal with sharks after the war cruiser USS Indianapolis sank in the Pacific theater at the end of World War II. At that moment the shark rams and damages the hull of the ship, after which it disappears again. The next morning the shark is sighted again and Brody tries to contact the Coast Guard, but Quint destroys the radio. After a long chase, the shark hunter manages to harpoon the shark again and ties it to the stern of the Orca, but the animal drags the ship and manages to flood enough to damage its engines. At that moment, Quint heads towards the coast with the intention of luring the intelligent shark and suffocating it in shallow water, but in his obsession with hunting such formidable prey, he blows up the engines of the Orca .

With the small boat immobilized and without a radio, the trio of men make a desperate attempt: Hooper dons his diving suit and dives into the water inside a cage, trying to stick a strychnine-laden hypodermic spear into the animal. The shark attacks the cage from behind and the jolt causes Hooper to lose his spear. The shark, in its ferocious attack, is trapped in the cage, a moment that Hooper takes advantage of to escape and hide on the seabed. Quint and Brody raise the empty cage, but at that moment the shark leaps onto the deck and smashes the stern of the small boat, causing it to sink. The ship tilts dangerously and Quint—not able to catch himself—slides into the jaws of the monstrous shark, stabbing it to no avail as it is bitten and dragged out to sea. The shark returns and enters the flooded cabin of the Orca, a circumstance that Brody takes advantage of to put a diving bottle in its jaws, after which it goes outside, takes Quint's Garand M1 rifle and climbs on it. to the mast as the ship sinks. The shark, with the bottle jammed between its teeth, begins to head towards Brody, who fires at it, intending to hit the pressurized bottle. Muttering "smile you son of a bitch," Brody lands the shot, blasting the shark to pieces. The policeman smiles with relief as the remains of the formidable shark sink.

Hooper reemerges from the water and laughs along with Brody, happy to have put an end to the nightmare. With the help of floating barrels, the two begin to swim back to shore.

Cast

Although the producers asked Spielberg to cast well-known actors, he preferred to cast non-star actors. He wanted anonymous performers to help viewers "believe that this was happening to people like you and me", whereas "stars carry a lot of memories and those memories can sometimes... corrupt history". furthermore that in his plans "the superstar was going to be the shark". Susan Backlinie, formerly a stuntwoman, would play Chrissie, who knew how to swim and was willing to strip. Most of the minor roles were played by locals from Martha's Vineyard, the location of filming. tape. This was the case for Deputy Hendricks, played by Jeffrey C. Kramer, who would later become a television producer.

Robert Duvall was offered the role of Brody, but was only interested in playing Quint. Charlton Heston expressed his desire to keep the role, but Spielberg thought he was too well-known a star to face the police chief from a modest town. Roy Scheider also became interested in the project after overhearing Spielberg in a conversation at a party in which the director was discussing jumping the shark into a boat. Spielberg was initially not entirely convinced. to cast Scheider, fearing he would play "too tough" a guy, similar to his character in The French Connection.

Nine days before filming began, there were no actors for the roles of Quint and Hooper. Lee Marvin and Sterling Hayden were offered the role of Quint, but both turned it down. Zanuck and Brown had just worked with Robert Shaw in The Coup and was pitched to Spielberg. Shaw was reluctant to accept the role because he had disliked Benchley's novel, but decided to agree at the urging of his wife, actress Mary Ure, and his secretary. Shaw based his portrayal on that of his co-star Craig Kingsbury, a local fisherman, farmer, and eccentric character who played Ben Gardner in the film. Spielberg described Kingsbury as "the purest version of what, in my opinion, it was Quint", and some of his lines and comments were incorporated into the script in dialogue by both Gardner and Quint.

For the role of Hooper, Spielberg initially cast Jon Voight, but Timothy Bottoms, Joel Gray and Jeff Bridges were also considered. The director's friend, George Lucas, approached Richard Dreyfuss, with whom he had worked on American Graffiti. This actor initially rejected the role, but changed his mind after watching the film The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, in which he starred and which I had just finished shooting. Disappointed with his own performance and afraid that no one would want to hire him once it came out, he immediately called Spielberg and accepted the role in Jaws . Because the film the director had seen was so different from the book on which it was based, Spielberg asked him not to read it. Once the cast was confirmed, Hooper's character was rewrote to better suit the actor, as well as to resemble Spielberg himself, who ended up seeing Dreyfuss as "my alter ego".

Production

Development

Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown Baren, producers at Universal Pictures, had separately heard of Peter Benchley's novel Jaws. Brown met the writer in the fiction department of Cosmopolitan magazine, then edited by his wife, Helen Gurley Brown. The editor of the magazine's literature section wrote a short summary of its plot and concluded with the comment "it could be a good movie". Both producers read the novel in one night and agreed the next morning that it was " the most exciting thing they've ever read" and that they wanted to produce a film version, although they weren't sure how it could be done. In 1973, before the novel was published, they bought its rights for US$175,000.). Brown stated that if he had read the book twice he would never have produced the film because he would have realized how difficult certain sequences were going to be to execute.

To direct the adaptation, Zanuck and Brown initially considered veteran filmmaker John Sturges—whose resume included a maritime adventure, The Old Man and the Sea—before offering the job to Dick Richards, who had directed his opera the year before. cousin, Courage, Sweat and Gunpowder. However, the producers became irritated by Richards's habit of describing the shark as a whale and he soon abandoned a project desired by 26-year-old filmmaker Steven Spielberg. years after he had directed his first film for the cinema, Loca evasion, produced by Zanuck and Brown. At the end of a meeting in his office, Spielberg picked up a copy of Benchley's as-yet-unpublished novel and was immediately captivated. He later noted that it was similar to his 1971 telefilm Duel, as in his words, in both stories "these leviathans attack anyone". After Richards' departure from the project, the producers hired Spielberg, who signed on in June 1973, before the release of The Crazy Escape.

However, before production got underway, Spielberg began to have second thoughts about the project for fear of being typecast as "the director of the truck and the shark". He wanted to direct The Adventurers instead. of 20th Century Fox's Lucky Lady, but Universal exercised its right under the director's contract to prevent his departure. Brown tried to convince Spielberg to go ahead with the film, saying that "after [Jaws], you can make all the movies you want." The film received an estimated budget of $3.5 million and a fifty-five day shooting deadline. Filming was scheduled to begin in May 1974, and Universal intended to finish filming by the end of June, when the production company's contract with the Screen Actors Guild expired, thus avoiding any interruption due to a strike.

Script

For the adaptation, Spielberg wanted to retain the basic concept of Benchley's novel, but also remove some of the subplots. He stated that his favorite part of the book was the shark hunt in the last 120 pages, and when he accepted the job he told Zanuck "I'd like to make the film if I can change the first two acts and base it on an original script, then be very faithful to the book in the last third." When the producers acquired the rights to the novel they promised Benchley that he could write the first draft of the film script. In total, he wrote three drafts before the script was turned over to other writers. When sending his latest version to Spielberg, he told him: "It's the best I can do." One of his changes was to remove the adultery issue. between Ellen Brody and Matt Hooper at the suggestion of Spielberg, who feared this would undermine the camaraderie of the three men aboard the Orca. During filming, Benchley agreed to return to the project to play a small role as reporter.

Spielberg, who felt that the characters in Benchley's script were still unsympathetic, invited the young screenwriter John Byrum to do a rewrite, but he declined. The creators of the television series Colombo, William Link and Richard Levinson, also declined an invitation from the director. Tony and Pulitzer Award-winning playwright Howard Sackler was in Los Angeles when the producers began looking for another screenwriter and offered to do a rewrite. Since the director and producers were not satisfied with Benchley's script, they quickly agreed.

Spielberg wanted "a certain lightness" for Jaws, with cute situations that would prevent the film from becoming "a hunt in a dark sea", so he turned to his friend Carl Gottlieb, a screenwriter and comic actor then working on the television sitcom The Odd Couple. Spielberg sent him a script, asking what he would change and if there were any roles in it he would be interested in playing. Gottlieb told him he returned three pages with notes and chose the character of Meadows, editor of a local newspaper. He passed an audition a week before Spielberg brought him in to talk to the producers about his involvement as a screenwriter.

Although their initial agreement was to polish the dialogue in just one week, Gottlieb eventually became the main writer and completely rewrote the script during the nine weeks of filming. The script for each sequence was usually finished writing the night before shooting, after Gottlieb had dinner with Spielberg and the cast and crew to decide what he would ultimately include in the film. Many lines of dialogue were the result of improvisation by the actors during these meals, and a few were already decided on the same filming set, in the case of the famous phrase ad lib. by Roy Scheider: "She'll need a bigger ship." John Milius helped polish some dialogue and The Escape writers Matthew Robbins and Hal Barwood also made minor contributions but do not appear in the scripts. credits. Spielberg claimed that he prepared his own draft, but it is unclear to what extent the writers relied on it. One specific alteration he made to the story was to change the shark's death from receiving numerous injuries to dying in the pressurized bottle explosion, as he thought audiences would like a "great moving finale" more. The director estimated that the final script had a total of twenty-seven scenes that were not in the original book.

Benchley had written Jaws after reading about the capture of a huge shark in 1964 by fisherman Frank Mundus. According to Gottlieb, Quint's character is loosely based on Mundus, for which he read the book Sportfishing for Sharks that he had published. Sackler came up with Quint's backstory as survivor of the USS Indianapolis disaster. The question of who wrote Quint's famous monologue on the Indianapolis has caused some controversy. Spielberg described it as a collaboration between Sackler, Milius, and actor Robert Shaw, who was also a screenwriter. According to the director, Milius turned Sackler's three-quarter-page speech into a monologue, which was later rewritten. by Shaw himself. Gottlieb attributes the authorship to Shaw and downplays Milius's contribution.

Shooting

"We started the film without a script, without a cast and without a shark." — actor Richard Dreyfuss on the rugged production of the film. |

Filming on Jaws began on May 2, 1974 on Martha's Vineyard (Massachusetts), a location selected after the possibility of shooting on Long Island was considered. Brown explained that the production "needed a lower-middle-class vacation area to make it look like shark attacks could destroy their tourist business." Martha's Vineyard was also chosen because the surrounding ocean has a sandy seabed that it does not go deeper than 11 meters down to 19 kilometers offshore, which helped make the propeller-driven mechanical shark easier to operate. Since Spielberg wanted to shoot underwater scenes to mimic what people see while swimming in the At sea, cinematographer Bill Butler had to devise new equipment that would allow filming at sea and underwater, including a water platform to keep the camera stable and away from the tides and a submersible waterproof box. Spielberg asked him the art department to avoid the color red both in the settings and in the clothing of the characters, so that the blood from the shark's attacks was the only element red item on the screen and thus cause a greater impact on viewers.

Three life-size air-powered shark replicas—dubbed "Bruce" by the team after Spielberg's lawyer Bruce Raimer—were built for the film: a bellyless watersled shark that was pulled by a a hundred-meter cable and two sharks on a platform, one that moved from left to right of the camera—on its opposite side it had numerous pneumatic hoses in view—and another exactly the same but in reverse. Art director Joe Alves designed the sharks in late 1973 and these were built between November of that year and April 1974 in Rolly Harper's Motion Picture & Equipment Rental in Sun Valley, in the San Fernando Valley, California. Its creation involved a team of about forty effects technicians supervised by renowned mechanical effects specialist Bob Mattey, best known for creating the giant squid featured in the 1954 film Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Upon completion, the sharks were transported by truck to the filming location. In early July the rig used to tow the two sharks in the side shots capsized while being submerged to the seabed, forcing a team of divers to to retrieve it. The shark model required fourteen people to power all of its moving parts.

The shoot was complicated and its budget skyrocketed. David Brown said that the budget "was four million dollars and the film ended up costing nine million". The special effects alone cost three million due to the team's problems with the mechanical sharks, and not in vain the most disgruntled members of the team. The team dubbed the film "Flaws" - "Flaws", for its similarity to "Jaws" - Spielberg attributed many of the problems to his perfectionism and inexperience. The former was made clear by his insistence on shooting in the sea with a life-size shark: "I could have shot the movie in a water tank or even in a sheltered lake somewhere, but it wouldn't have looked the same." As for his lack of experience, he said, "I was naive about the ocean, basically. Deep down I was pretty naive about Mother Nature and the arrogance of a filmmaker who believed he could beat the elements was reckless, but I was too young to realize it when I demanded to shoot the film in the Atlantic Ocean and not in a tank. of water in Hollywood".

Shooting at sea caused numerous delays: ships that weren't supposed to appear slipped onto the screen, cameras got wet, and once the ship Orca began to sink with the actors on board. Mechanical sharks broke down too often due to various circumstances, such as bad weather, salt water entering through pneumatic hoses, their structure fracturing due to water pressure, their covering skin corroding, and electrolysis.. From the first sea trial the "non-absorbent" neoprene foam that made up the sharks' skin became soaked with water and swelled them. In addition, the shark replicas often became entangled in seaweed. Spielberg later calculated that, of the average twelve working hours per day, only four were filming. Gottlieb, the screenwriter, was nearly killed. decapitated by a ship's propellers and Dreyfuss was trapped in the underwater cage. Additionally, the actors suffered motion sickness from the rocking of the ships. Shaw left for Canada whenever he could because he had tax problems, drank too much, and resented Dreyfuss, who was receiving rave reviews for his role in Duddy Kravitz. Editor Verna Fields had little filming. with which to work during filming, because according to Spielberg: "we shot five scenes on a good day, three on a normal day and none on a bad day".

Delays were fortuitous in some cases. The script was retouched during filming and the highly unreliable mechanical sharks forced the director to shoot many scenes in which the presence of the shark was only suggested. For example, during much of the animal's hunt its location is only indicated by the floating yellow barrels. pulled by cables that simulated a shark attack. Spielberg also included numerous shots showing only the shark's dorsal fin. This enforced restraint in showing the animal paradoxically added to the suspense of the film. As Spielberg noted years later: "The film went from being like a Japanese Saturday afternoon horror movie to being like Hitchcock movies: the more the less you see, the more suspense." In another interview, he said something similar: "The damaged shark was a godsend. It made me look more like Alfred Hitchcock than Ray Harryhausen." The performances were crucial in convincing the audience of the presence of a large shark: "The more fake the shark seemed in the water, the greater was my anxiety to improve the naturalism of the performances."

Ron and Valerie Taylor filmed shots of real sharks in Australian waters, with a tiny actor in a tiny cage to create the illusion that the sharks were huge. During the filming of the Taylors, a true great white attacked the boat and the empty cage, resulting in some impressive footage that Spielberg wanted to incorporate into the film. The problem was that there was no one inside the cage at the time of that filming and according to the novel it was Hooper who was inside trying to kill the shark, so the script had to be modified: Hooper had already escaped from the cage, making it possible to include filming of the actual attack. As executive producer Bill Gilmore noted, "The Australian shark rewrote the script and saved Dreyfuss's character."

Shooting was scheduled to last 55 days, but ended on October 6, 1974, 159 days after it began. Spielberg, reflecting on the lengthy shoot, stated, "I thought my career as a filmmaker was over. I heard rumors... that I would never work again because no one had ever shot a movie for more than 100 days." Spielberg himself was not present when the film's final scene, the shark explosion, was filmed, because he thought the crew he was planning to throw it into the water when the scene was finished. Since then, it has become a tradition that this director is not present at the filming of the last scenes of his films. Later, underwater scenes were shot in a water tank from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in Culver City, where stuntmen Dick Warlock and Frank James Sparks stood in for Dreyfuss in the cage attack scene, and other shots near Santa Catalina Island, California. The ship Orca was transported to Los Angeles so that the sound effects team could record tracks for both the ship and the underwater scenes. Editor Verna Fields, who had completed a first cut of the first two thirds of the film, before the shark hunt, he finished all the editing and reworked some scenes. According to Zanuck, "She actually stepped in and reworked some scenes that Spielberg had constructed comically to make them more terrifying, and other scenes that he shot terrifying and made them comical."

Two scenes were altered after pre-general release screenings of the film. Because Scheider's utterance "You'll need a bigger ship" had been obscured by the screams of the audience, the scene of his shock reaction after the appearance of the shark was lengthened and the volume of the phrase was raised. Spielberg he also decided he wanted "one more scream", and reshot the underwater scene in which Hooper discovers the dead body of Ben Gardner. For this he had to put 3000 USD out of his pocket because Universal refused to pay for the new filming. This underwater scene was filmed in the swimming pool at Fields Publishing House in Encino, California, using a latex model of Craig Kingsbury's head glued to a mannequin that was placed on the hull of the sunken ship.

Soundtrack

John Williams composed the music for the film, a work that won him an Oscar for best score and was later placed sixth on a list of the best soundtracks compiled by the American Film Institute. The celebrated main theme is a simple alternation of two musical notes that has become a classic piece of suspense music, synonymous with very close danger. The piece was performed on the tuba by Tommy Johnson. When Johnson asked Williams why he wrote the melody in such a high register and why it wasn't played by a more appropriate instrument like the French horn, Williams replied that he wanted "to make it sound a little more threatening". first showing the melody to the conductor, playing the only two notes on a piano, Spielberg claims he laughed thinking it was a joke. Because Williams saw similarities between Jaws and pirate movies, in other passages he evoked "pirate music", which he called "primitive, but fun and entertaining". soundtrack also contains echoes of The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky.

Various interpretations exist as to the meaning and effectiveness of the theme song for Jaws, which is widely described as one of the most recognizable movie themes of all time. Music scholar Joseph Cancellaro proposes that the sound produced by the two notes imitates the shark's heartbeat. According to Alexandre Tylski, this music suggests human breathing, in the same way that Bernard Herrmann created for Taxi Driver, North by Northwest and The Mysterious Island. He further argues that the strongest motif in the score is actually "the split, the rupture"—when it cuts off dramatically after Chrissie's death. The soundtrack also makes clever use of the relationship between sound and silence: viewers are conditioned to associate the shark with its subject, something that is exploited in the final climax of the film, when the animal appears without a musical introduction.

Spielberg later said that without Williams' score the film would have been half as successful, and Williams himself admits that it catapulted his career. Williams had previously scored Spielberg's debut, The Sugarland Express, and since then she has collaborated with him on all of his films except The Color Purple and Ready Player One. The original soundtrack to Jaws was released by MCA Records in 1975, and in 1992 it appeared on CD including almost an hour and a half of music that Williams remade for the album. In 2000 they appeared two versions of the music: Decca/Universal released the album to coincide with the 25th anniversary DVD edition, with the original fifty-one minute soundtrack, and a new recording of the score was released by Varèse Sarabande performed by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra with Joel McNeely conducting.

- List of topics

| N.o | Title | Duration | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | «Main Title (Theme From "Jaws") | 2:20 | ||||||||

| 2. | «Chrissie's Death» | 1:42 | ||||||||

| 3. | «Promenade (Tourists on the Menu)» | 2:47 | ||||||||

| 4. | «Out to Sea» | 2:29 | ||||||||

| 5. | «The Indianapolis Story» | 2:26 | ||||||||

| 6. | «Sea Attack Number One» | 5:26 | ||||||||

| 7. | «One Barrel Chase» | 3:07 | ||||||||

| 8. | «Preparing the Cage» | 3:28 | ||||||||

| 9. | «Night Search» | 3:33 | ||||||||

| 10. | "The Underwater Siege" | 2:34 | ||||||||

| 11. | "Hand to Hand Combat" | 2:32 | ||||||||

| 12. | «End Title (Theme From "Jaws") | 2:21 | ||||||||

| 34:16 | ||||||||||

Dubbing into Spanish

Two dubbings were made: one for Spain and another for Latin America. In the European case, which was dubbed at the Voz de España studio in Barcelona, the cast was divided by Dionisio Macías (voicing the boss Martin Brody), Antonio García Moral (for Matt Hooper), Elsa Fábregas (Ellen Brody), Rafael Luis Calvo (as Mayor Larry Vaughn), Constantino Romero (Leonard Hendricks), Arsenio Corsellas (Sam Quint), Mario Gas (Tom Cassidy), Felipe Peña (for the voice of Charlie), Claudi García (as the man who is in the boat), Vicens Manuel Domenech who doubled three characters (mortuary doctor, Ben Gardner and Harry Wiseman), Carmen Robles (as Polly, chief Brody's secretary), Juan Comellas (for the reporter), Pepe Mediavilla (to do minor additional voices) and Enriqueta Linares (as the woman in the meeting).

Regarding the Spanish-American version, the dubbing was done in a studio located in Mexico City. Then the cast was made up of Pedro d'Aguillon (as the boss Martin Brody), Carlos Becerril (Matt Hooper), Rommy Mendoza (Ellen Brody), Paca Mauri (for Sam Quint), Arturo Mercado (Larry Vaughn), Rafael Rivera (Leonard Hendricks), Guillermo Coria (to double the reporter), Carlos Díaz (in the role of the boy who was in the boat) and, finally, Jorge Roig (in the roles of the diverse voices of the environment).

Inspiration and themes

The most obvious artistic antecedent of Jaws is the novel Moby-Dick by Herman Melville. Quint's character is reminiscent of Captain Ahab, the captain of the Pequod obsessed with hunting a white whale. Quint's monologue reveals his similar obsession with sharks, and even his boat, the Orca , is named after the natural enemy of sharks. In the novel and the original screenplay, Quint dies after being dragged underwater with a harpoon attached to his leg, an ending similar to that of Ahab in Melville's novel. A direct reference to these is found in Spielberg's draft. similarities, since Quint's character appears for the first time watching the 1956 film Moby-Dick. However, Gregory Peck, protagonist of this adaptation of the literary classic and owner of its copyright, did not provide the necessary license to add the scene in Jaws. Screenwriter Carl Gottlieb also incorporated some similarities to Ernest Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea: "Jaws is... a struggle titanic, like Melville or Hemingway."

Underwater scenes showing the shark's perspective were compared by writer John Brosnan to those of two 1950s films, Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Monster That Challenged the World. Gottlieb named two science fiction films from the same period as influences for the way in which the predator's rare appearances are produced: The Thing from Another World, which he described such as "a great horror movie where you only see the monster at the end", and It Came from Outer Space, where "the suspense is a consequence of the creature being always out of shot". These precedents helped Spielberg and Gottlieb "focus on showing the 'effects' of the shark rather than the shark itself".

The critic Neil Sinyard has detected similarities with a work by Henrik Ibsen, An Enemy of the People. Gottlieb himself has said that he and Spielberg were referring to Jaws as "Moby-Dick added to An Enemy of the People". Ibsen's work introduces us to a doctor who discovers that the medicinal thermal waters in a coastal town are contaminated. These waters represent a great tourist attraction and a considerable source of income for this place, but when the doctor tries to convince the locals of the danger of contaminants to health, he loses his job and is rejected. This plot has its parallels with that of Jaws in Brody's confrontation with the mayor of Amity Island, who refuses to acknowledge the presence of a large shark that could end the summer tourist season. Brody is vindicated when new shark attacks occur on the crowded beaches during the day. Sinyard calls the film "a clever combination of the Ibsen and Watergate stories".

Interpretation

The Jaws argument has been interpreted in various ways. Stephen Heath linked some ideological aspects of the film to the then-recent Watergate scandal, arguing that Brody represents the "middle-class white man — there is not a single black character and very few women in the film — who restores order." audience with a heroism born of fear and decency". However, Heath goes beyond the ideological content in his analysis to examine the film, as an example of an "industrial product" sold on the basis of "the pleasure of cinema"., helping the perpetuation of the industry —part of the meaning of Jaws is precisely to be the most profitable film—».

Andrew Britton contrasts the film with the post-Watergate cynicism addressed in the book, suggesting that the alterations made to the novel's narrative—Hooper's survival, the shark's explosive death—help create "a collective exorcism, a ceremony for the restoration of ideological trust. He suggests that the film's experience is "inconceivable" without the jubilation of viewers when the predator is slain, which means the destruction of the evil itself. According to Britton, Brody serves to demonstrate that "the individual action of one man continues being a viable source for social change." Peter Biskind argues that this film maintains the post-Watergate cynicism about politicians and the world of politics in the fact that the only villain, other than the shark, is the irresponsible mayor of the location. However, he notes that far from the formulas often employed by New Hollywood-era filmmakers—that is, us against them, counterculture against the authorities—the global conflict in Jaws is not based on the concept of heroes against authority, but against what threatens us all, regardless of our socioeconomic position.

While Britton points out that the film does not address the social class conflicts on Amity Island that do appear in the book, Biskind detects class divisions in the film and opines on its meaning: "authority It must be restored, but not by Quint. Of the sailor he says that his "working-class toughness and bourgeois independence from him is strange and frightening...irrational and out of control." Hooper, for his part, "is associated more with technology than experience, with inherited wealth rather than hard-earned self-sufficiency", and stands apart from the film's climactic moment. Britton considers the film more intent on in showing "the vulnerability of children and the need to protect them", which in turn helps generate a "general sense of the supreme value of family life: a value clearly related to stability and cultural continuity".

The Marxist analysis elaborated by Fredric Jameson highlights the polysemy of the shark and the multiple ways in which it can be and has been interpreted: from representing foreign threats such as communism or the Third World, to more intimate fears such as the unreality of life modern Americanism and the futile efforts to suppress the knowledge of death. He asserts that its symbolic function is found in a "polysemy that is profoundly ideological, insofar as it allows social and historical anxieties to revert to seemingly natural things... contained in what seems to be a conflict with other forms of biological existence." Jameson sees Quint's death as the symbolic destruction of the old, populist New Deal-era America and the partnership between Brody and Hooper as an "allegory of an alliance between the forces of law and order and the new technocracy." of multinational corporations...in which the viewer rejoices without understanding if he or she is excluded".

Journalist Neal Gabler believes that the film shows three different ways of overcoming an obstacle: the scientific way (played by Hooper), the spiritual way (played by Quint), and the common man way (played by Brody). The latter is the one that is successful in the film.

Premiere

Promotion

Production company Universal spent $1.8 million promoting Jaws, $700,000 of which went toward an unprecedented television campaign. The media blitz included twenty-five media ads minute that aired at night, in prime time, between June 18, 1975, and the film's release two days later. Beyond that, film industry expert Searle Kochberg states that Universal "devised and he coordinated a very innovative plan for the commercialization of the film." As early as October 1974, Zanuck, Brown, and Benchley had appeared on television and radio shows to promote the book Jaws and its upcoming film adaptation. film. The studio and Bantam publishers reached an agreement to use the same image on both the book cover and the film poster. The central pieces of the joint promotional strategy were the theme song created by John Williams and the promotional poster showing the head of a huge shark heading towards an unsuspecting beachgoer. This famous poster was based on the cover of Benchley's book, both done by Bantam artist Roger Kastel. Seiniger advertising agency It took him six months to design the poster for the film. Its director Tony Seiniger said of the famous poster: "No matter what we did, it didn't look scary enough." Therefore, Seiniger ultimately decided that the underside of the shark had to be shown to show its enormous teeth.

To take advantage of the premiere of the film, numerous advertising and commercial products were created that were inspired by it. Graeme Turner wrote in 1999 that Jaws was accompanied by what was probably "the largest array of associated merchandise" for any film to date, "including the soundtrack album, T-shirts, glasses of plastic, a book about the filming of the movie, the novel it was based on, beach towels, blankets, shark costumes and dolls, games, posters, pajamas, water guns, shark tooth necklaces and more." For example, the Ideal Toy Company created a board game in which the player had to use a hook to fish things out of a shark's jaws before it closed them.

Theatrical release

The satisfactory response from viewers at two preview showings of the film's first cut—in Dallas on March 26, 1975, and in Long Beach two days later—as well as the success of Benchley's novel and the early stages of the advertising campaign deployed by Universal, generated great interest among theater owners and facilitated the studio's plans to release the film in hundreds of theaters simultaneously. On April 24, a third and final film was held in Hollywood screening prior to the general release that incorporated the small changes in the editing inspired by the two previous screenings and already mentioned in the chapter on filming. When Lew Wasserman, head of Universal Studios, attended one of these screenings, ordered that the total number of theaters in which the film would initially be shown on its debut, which was originally nine hundred, be reduced, declaring "I want this film to be released." I was going all summer. I don't want the people of Palm Springs to see the film in Palm Springs, I want them to take their cars and come to Hollywood to see it." Despite this, the several hundred theaters that were scheduled to show Spielberg's film in its opening They then represented an unusual premiere in the world of cinema.

At that time, mass releases were associated with films of dubious quality, which in this way diminished the effect of negative reviews and word of mouth. There were some recent exceptions, such as the revival of Billy Jack and its sequel The Trial of Billy Jack, the sequel to Dirty Harry, Magnum Force and the latest installments of James Bond. Even then, the typical premiere of the big production companies was made in a few cinemas in big cities, which allowed for several premieres. The enormous success of The Godfather in 1972 had started a trend of mass releases, but even this film was initially released in only five theaters before more copies shipped for its second weekend.

Jaws opened on June 20 in four hundred and sixty-four theaters in North America—four hundred and nine in the United States and the rest in Canada. novel television advertising campaign created a form of theatrical release never seen before. Sid Sheinberg, president of Universal, concluded that the costs of national trade promotion would be amortized by more favorable revenue per print than if the film had been distributed in a slower and more staggered manner. In view of the commercial success of Tiburón, its release was expanded on July 25 to almost seven hundred theaters, and by August 15 to more than nine hundred and fifty. International distribution followed the same pattern, with intensive television campaigns and massive releases. The film's worldwide releases are listed below:

| International premiere dates |

|---|

Reception

Commercial

Jaws grossed $7 million in its opening weekend and had recouped its production costs in just two weeks. After 78 days in theaters it surpassed The Godfather as the highest-grossing film in history in the United States, with 100 million in its collection, which exceeded the 86 obtained by Francis Ford Coppola's film. In its original premiere, it grossed 123.1 million, and with its revivals in 1976 and 1979 it reached the figure of 133.4.

The film was released internationally in December 1975 and was equally successful, breaking records in Singapore, New Zealand, Japan, Spain, and Mexico. By 1977, Jaws was the #1 movie highest grossing worldwide, with 193 million in profits, which brought its income to a total of 400 million. With this, it far exceeded the 145 million that The Godfather had obtained a few years before.

Jaws was the highest-grossing film until the release of Star Wars in 1977, which surpassed it after six months in theaters and set a new record in 1978. As of August 2018, Jaws is ranked 212th on the list of the highest-grossing films in cinema history, with $470.7 million in total earnings, and is number 72 on the list of the films that have obtained the most money in the United States thanks to its 260 million. If we adjust the figures for inflation, Jaws grossed two billion according to 2011 prices, and is the second most profitable franchise after of Star Wars. movies sold in its day. On television, Tiburón was broadcast for the first time by the American Broadcasting Company chain after its rerun of e 1979, a broadcast that reached a 57% audience, the second best figure for screen share after that achieved by Gone with the Wind.

Criticism

Anglo-Saxon and other countries

The film was widely acclaimed by critics. In the United States, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times called it "a sensationally effective action movie, a thriller that works better because it is populated with very well developed characters.” A.D. Murphy of Variety praised Spielberg's directing skill and called Robert Shaw's performance "absolutely magnificent". According to Pauline Kael of The New Yorker, it was "the most utterly wicked scary movie of all time... with more zest than any of the early Woody Allen movies, so much more electrifying, and funny in a Woody Allen kind of way". New Times, Frank Rich wrote: "Spielberg has been blessed with a talent absurdly absent from most of today's American filmmakers: this man really knows how to tell stories on the screen... It speaks well of the gifts from this director the fact that the scariest scenes in the film are the ones where we don't even see the shark." Judith Crist, critic for New York magazine, described the film as "adventurous and exciting entertainment of the highest order. » and praised their performances and « extraordinary technical achievements". Rex Reed praised the "unnerving" action sequences, concluding that "for the most part, Jaws is a terrifying horror film in every respect".

In the UK and Australia the film was met with positive reviews. Peter Bradshaw of the British newspaper The Guardian said "don't listen to the cynics, this is a masterpiece". Also in the UK, in TimeOut magazine , critic Tom Huddleston wrote that "nearly forty years later, we feel the eternal and terrifying fear that one felt when attacked by a shark", also adding that "it is the mark that excellent work leaves behind". Australian website Webwombat.com.au, James Anthony commented on his good impression in the most active moments of the film.

But the film was not without its detractors, especially in the United States. Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that "You can judge the movie by the fact that we have no sympathy for any of the shark victims... In good movies, the characters are revealed in moments of action. In movies like this, the characters are simply anonymous to the action...like puppets offering information when needed." However, he also added that "it's the kind of nonsense that can be a good dose of fun". they put the movie on, because it was too scary for kids and was probably stomach-churning at such a young age. It's a coarse-grained, exploitative piece of work that is overly reliant on its impact". tape", but of the first half, he opined that it was "flawed, often, by its busyness". Finally, William S. Patcher of Commentary, described the film as "a meal to numb the minds of the sated gluttons of cinema, especially in this manipulative genre," while The Village Voice, in the words of its critic Molly Haskell, said that watching the film "makes you feel like a rat in mental health therapy." shock".

Hispanic American and Spanish

In Latin America Tiburón also received very good reviews. In Argentina, the website Piratas del Cine praised the actors, saying that "the cast was perfect", as well as its soundtrack, commenting that "it would be remembered forever". Alejandro Alemán, of the newspaper El Universal de México, wrote: "Just the third feature film by a then unknown 27-year-old named Steven Spielberg, it is one of the best fables Hollywood can count on."

In Spain the reviews were mostly positive. The website Fotogramas gave it four stars out of five. Critics on the website Muchocine.net said that it was "an impressive film, magnificently shot and whose recognition took time to arrive. Spielberg in its purest form". big screen with Crazy Evasion, the young Spielberg billed with this film his first great work and monumental success at the box office”, something in which the website Return agreed, saying that “with only two feature films to his backs, The Devil on Wheels (Duel, 1971) and Crazy Escape (1974), Steven Spielberg reaped with Jaws an overwhelming success".

Awards and recognitions

Jaws won three Oscars: Best Editing, Best Score and Best Sound — Robert Hoyt, Roger Heman, Earl Madery and John Carter. It was also nominated in the Best Picture category, but this recognition went to to One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. Spielberg regretted not being nominated for best director. In addition to the Oscar, John Williams won the Grammy Award, the BAFTA Award for his score and the Golden Globe. For her part, Verna Fields was awarded, in addition to the Academy Award, with the Eddie Award from the United States Film Editors for Best Editing.

Jaws was also voted Favorite Film at the People's Choice Awards. It was nominated for Best Film, Actor (Richard Dreyfuss), Editing and Sound at the 29th BAFTA Awards. and for best film -in the drama category-, director and screenplay at the Golden Globes. Spielberg was nominated for the Directors Guild of America awards, while the Writers Guild did the same for Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb in its Best Drama Adaptation category.

Since it was released, Jaws has been frequently listed by film critics and industry professionals as one of the greatest films of all time. It entered at number 48 on AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies from the American Film Institute which was compiled in 1998, though it dropped to number 56 on the 10th anniversary list. The American Film Institute also included the shark at number 18 on its list of the 50 Greatest Movie Villains, with Roy Scheider's "He's gonna need a bigger boat" at number 35 on the 100 Greatest Villains. phrases from the cinema, to the soundtrack of Williams in the 6th of the 100 best soundtracks and the film in second place of the best thrillers of all time, only behind Psycho. In 2003 The New York Times included Jaws in its list of the 1000 best films and the following year the television channel Bravo placed it in the first position of the 100 most terrifying moments of cinema. The Chicago Film Critics Association named it, in 2006, as the sixth most terrifying film ever filmed and In 2008, Empire magazine ranked it fifth on its list of the 500 Greatest Movies of All Time and Quint's character as the 50th most interesting on a list of the 100 Greatest Movie Characters. Many other lists always include it among the 50 or 100 greatest films. In 2001 the United States Library of Congress selected Jaws for preservation in the National Film Registry as a "culturally significant" film. In 2006 the Writers Guild of America selected his screenplay as the sixty-third best in film history.

Legacy

Jaws demonstrated that more could be gained from a simultaneous theatrical release, backed by extensive television advertising, than from the hitherto usual slow, staggered releases in which films reached new markets with too much time difference. The perfected method for the launch of this production is the one that has prevailed in Hollywood since then. The film was a true milestone because it began a new commercial strategy of the studios of Hollywood based on intensive advertising campaigns that included numerous television commercials, on the launch of a complete marketing associated with the films and on the simultaneous release of the films in thousands of cinemas, many of them located in the new shopping centers in the suburbs. of the cities.

According to Peter Biskind, Jaws "downplayed criticism in the press and made it very difficult for other films to make a slow, incremental profit, finding their audience through quality, simply... Furthermore, this production whetted the production companies' appetite for quick big profits, meaning that the studios wanted every movie to be Jaws". Expert Thomas Schatz writes that this film "recalibrated the potential earnings from the Hollywood hit, and further redefined its status as a commercial asset and cultural phenomenon. The film put a definitive end to a recession in Hollywood that had lasted five years and that was due to the decrease in the number of viewers, who at that time were of more diverse origins due to the arrival of those born during the birth explosion after the 1990s. the Second World War. These new and young viewers were less attracted to the epic musicals and historical productions that had dominated Hollywood cinema in the 1950s and 1960s. Steven Spielberg's film marked the beginning of an era of expensive, high-priced productions. high-tech and frantically edited thrillers.”

Since the premiere of Jaws the summer season was established as the most important for the premiere of the great cinematographic productions, those that pretended to be great successes. The most anticipated productions were in winter, while the summer season was reserved for the screening of films that generated less expectation among the public. It is remembered Jaws and Star Wars as the films that marked both the beginning of the new business model of the film industry in the United States, dominated by films with simple premises -easy to remember and sell-, and the beginning of the New Hollywood period, in which the auteur films began to be ignored in favor of the profitability of large productions. In the New Hollywood era, directors began to be limited in their film interests, in favor of production companies that now controlled everything and l system to make sure you get a lot of profit. In Biskind's words, "Spielberg was the Trojan horse through which studios began to assert their power."

The film also had wide-ranging cultural repercussions. In a similar way to how one of the scenes in Psycho created a certain fear of getting into the shower during the 1960s, Tiburón caused a panic to bathe in the sea due to the possible attack of a shark. The reduction in the number of bathers on the beaches in 1975 was attributed to the film, as well as the increase in shark sightings. Still today, several decades after its release, negative stereotypes about sharks and their behavior are perpetuated This film is also credited with the "Shark Effect", which supposedly led to increased capture of these marine predators by fishermen. Benchley went on to say that he would not have written his novel if he had known how they really behaved sharks in their natural environment. Conservation groups have lamented the fact that the film's fame has hampered efforts to convince people that sharks need protection.

This film created a model followed by many horror films. So much so that another mythical film such as Alien, the Eighth Passenger, directed in 1979 by Ridley Scott, was sold to studio executives as "Shark in Space". In the 1970s and 1980s, numerous films starring man-eating animals, usually aquatic, were released, such as Orca, the Killer Whale, Grizzly, The Beast under asphalt, The Day of the Animals or Death Trap. Spielberg declared Piranha, directed by Joe Dante and written by John Sayles, to be "the best of the Jaws-inspired rip-offs". Three aquatic monster films came from Italy: The Last Shark , which was sued by Universal for plagiarism, The Ocean Devourer and Jaws 5: Cruel Jaws, which also featured footage from Jaws and Shark 2.

The 30th anniversary of the release of Jaws was celebrated on the island of Martha's Vineyard in 2005 with the JawsFest festival. An independent group of fans created the documentary The Shark is Still Working, featuring interviews with various actors and cast members from the film. Narrated by Roy Scheider and dedicated to Peter Benchley, who died in 2006, it premiered in 2009 at the Los Angeles United Film Festival.

Aftermath

Jaws spawned three direct sequels. The saga, according to estimates by Forbes, accumulated a total of 182,557,600 entries in the United States alone, however, of the sequels, none could repeat the success of the original; even the sum of all its earnings does not come close to what the first one earned. In October 1975 Spielberg told film festival attendees that "making a sequel is just a cheap sideshow trick". was considered joining the first sequel when its director, John D. Hancock, was fired just days before shooting began. Finally, his obligations with the filming of Close Encounters of the Third Kind , in which Dreyfuss starred precisely, made it impossible. Jaws 2 ended up being directed by Jeannot Szwarc and the actors Scheider, Gary, Hamilton, and Jeffrey Kramer reprized their characters. This first sequel is generally considered the best of all. Jaws 3-D was released in 1983 under the direction of Joe Alves, who had worked as art director and production designer, respectively, on the two previous ones. Starring Dennis Quaid and Louis Gossett, Jr., this film was released on the big screen in 3D, although this format was not transferred in its domestic editions. Jaws, the revenge , was It was shot in 1987 and starred Michael Caine and Lorraine Gary, already in the role of Brody's widow. Directed by Joseph Sargent, this film is considered one of the worst of all time. Although these three sequels made quite satisfactory amounts of money, critics and viewers were generally not satisfied with their quality.

Adaptations and Marketing

The film inspired two theme park attractions: one at Universal Studios Florida, which closed in January 2012, and another at Universal Studios Japan. Two musical adaptations were also made: JAWS The Musical!, which premiered at the 2004 Minnesota Fringe Festival, and Giant Killer Shark: The Musical, which premiered at the 2006 Toronto Fringe Festival. Three video games have been based on the film: Jaws, developed in 1987 by LJN for the Nintendo Entertainment System; Jaws Unleashed in 2006 by Majesco Entertainment for Xbox, PlayStation 2 and PC; and Jaws: Ultimate Predator, released in 2011 also by Majesco for Nintendo 3DS and Wii. In 2010 a mobile video game created by Bytemark was released for iPhone.

Home format

Jaws was the first motion picture title to be released on LaserDisc in North America, released by MCA DiscoVision in 1978. A second LaserDisc was released in 1992, before the third and last version released in 1995 as part of the MCA/Universal Home Video Signature Collection. The latter product was a box set including outtakes and deleted scenes, a two-hour documentary produced and directed by Laurent Bouzereau showing how the film was made, a copy of the novel Jaws, and a Williams soundtrack CD.

In 1980 MCA Home Video released Jaws for the first time in VHS format. In 1995, on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary, MCA Universal Home Video released a Collector's Edition that included retrospective of the film's production process. This edition sold 800,000 copies in North America alone. The last VHS edition appeared in 2000, the twenty-fifth anniversary of production, accompanied by a second tape with a documentary, deleted scenes, outtakes fakes and a trailer.

Also in the year 2000 and on the occasion of its quarter century, Jaws was released on DVD and its release was heralded by a massive publicity campaign. It contained a 50-minute documentary about the process of the making of the film – edited from the one that accompanied the 1995 LaserDisc – with interviews with Spielberg, Scheider, Dreyfuss, Benchley and other members of the team, in addition to the usual extras of deleted scenes, outtakes, trailers, production photos and storyboard This DVD sold a million copies in just one month. In June 2005 the 30th anniversary DVD edition was presented at the "JawsFest" festival on Martha's Vineyard, spiced up with extras already seen before, such as Bouzereau's documentary and an interview with Spielberg in 1974 on the set of the film. Finally, Jaws was released on Blu-Ray in August 2012, with sound and image fully restored for high definition from negative of original camera and four hours of bonus content, including the recent documentary The Shark Is Still Working. This Blu-Ray was released as part of Universal Pictures' 100th anniversary celebrations and debuted at number four, with 362,000 copies sold.

Contenido relacionado

Anthony daniels

George C Scott

Rock in Spanish