Japanese language

The Japanese language or Japanese language (日本語, ![]() Nihongo (?·i)?) It is a language of East Asia spoken by about 128 million people, mainly in Japan, where it is the national language. Japanese is the main language of the Japanese languages that are not genetically related to other languages, that is, isolated languages.

Nihongo (?·i)?) It is a language of East Asia spoken by about 128 million people, mainly in Japan, where it is the national language. Japanese is the main language of the Japanese languages that are not genetically related to other languages, that is, isolated languages.

Little is known about the origin of the language. There are 3rd century Chinese texts documenting some Japanese words, but the first long texts do not appear until the 8th century. During the Heian period (794-1185), Chinese exerted a profound influence on the vocabulary and phonology of Old and Early Middle Japanese. Late Middle Japanese (1185-1600) is substantially close to contemporary Japanese. The first European loans were also incorporated in this period. After the end of isolation in 1853, the amount of borrowing from European languages increased considerably, especially from English.

Although the language has no genetic relationship to Chinese, Japanese writing uses Chinese characters called kanji (漢字) and much of the vocabulary comes from Chinese. Along with the kanji, Japanese uses two syllabaries: the hiragana (ひらがな) and the katakana (カタカナ). The Latin alphabet (in Japanese romaji) is used to write acronyms and the language employs both Arabic and Chinese numerals.

Origin and classification of Japanese

Although native to northeast Asia, its phylogenetic relationship is uncertain. It has commonly been classified as a language isolate, as it has not been possible to establish a relationship with other languages, that is, a language unrelated to any other. However, according to some linguists, Modern Standard Japanese is not an isolated language but is part of the Japonic family along with several languages of the Ryūkyū Islands (also considered Japanese dialects) all of which are derived from Proto-Japonic. Apart from its modern descendants, however, no unequivocal phylogenetic relationship between Proto-Japonic (or its modern descendants) and any other language in Asia has been demonstrated. However, although no clear relationship has been firmly established, there is no shortage of hypotheses that point to some coincidences with Korean and with the Altaic or Austronesian languages. The ancient language of the Goguryeo kingdom, called Goguryano, shows similarities that could be due to a phylogenetic relationship, unfortunately this language is poorly documented. It should also be noted that Japanese is neither phylogenetically nor typologically related to Chinese, although an important part of the vocabulary of modern Japanese are borrowings and cultisms taken from classical Chinese. Nor does there seem to be any relationship with the Ainu language (with which it shares typological features, but not elements that suggest a common phylogenetic origin). It is a proven fact that there are systematic correlations between the phonemes of the primitive Korean languages and Old Japanese. However, it is not yet clear whether these correlations are due to a common origin or to massive lexical borrowings throughout the ages. centuries, the product of cultural exchange. An alternative theory ascribes this language to the macrofamily of Austronesian languages. According to this hypothesis, the Japanese language forms the northern end of a group that includes the aboriginal languages of Taiwan, Tagalog and other languages of the Philippines, and Malay-Indonesian in all its variants. In general, contemporary research oscillates between both hypotheses: it recognizes a strong continental influence, possibly linked to Korean, and, at the same time, considers the possibility of the existence of an Austronesian substratum.

From 250 B.C. C. the Yayoi peoples who arrived from the Asian continent began to populate the islands of the Japanese archipelago, where the development of an archaic language (Yamato kotoba - 倭言葉) with a polysyllabic structure began, as well as their own culture.. It would not be until the III century d. C. when Korean intellectuals introduce Chinese culture to the Japanese islands. This cultural invasion lasted for approximately four centuries, during which science, arts, and religion were introduced, as well as the Chinese writing system.

The Japanese began to use Chinese characters (kanji - 漢字 means Han characters) keeping the original Chinese sound, (although adapting it to their own phonetic system) and also adding the native pronunciation to those symbols. Therefore, today, when studying the kanji system, it is necessary to learn both the Chinese reading (onyomi 音読み) and the Japanese reading (kunyomi 訓読み), although these adjectives should not be misleading: Both pronunciations are typical of Japanese, and are different from those of modern Chinese, even so, the sound of onyomi is the Japanese approximation to the Chinese sound of the time and also depended on the variant spoken who was in power. In addition to the kanji, in Japanese there are two syllabaries to represent all its sounds, created from the simplification of certain kanji. The syllabaries are called hiragana and katakana and are a writing system unique to Japanese, absent from Chinese and Korean. Modern Japanese uses all three writing systems, kanji, hiragana, and katakana, circumscribing the use of each for different functions, although there are times when two of them can be used interchangeably.

Due to Japan's unique history, the Japanese language includes elements absent from Indo-European languages, one of the best known being a rich system of honorifics (keigo 敬語) that result in specific verb forms and grammatical constructions to indicate the relative hierarchy between the speaker and the listener, as well as the level of respect towards the interlocutor.

Geographic distribution

Japanese is most widespread, of course, in Japan, where it is spoken by most of the population. There are Japanese immigrant communities in Hawaii that also use the language (more than 250,000, 30% of the population), in California (United States) about 300,000; in Brazil about 400,000 and a significant number in Argentina and on the coast of Peru, as well as other parts of the world. In the former Japanese colonies such as Korea, Manchuria (China), Guam, Taiwan, the Philippines, the Marshall Islands and Palau, it is also known for the elderly who received school instruction in this language. However, most of these people prefer not to use it.

Geographic dialect variants

Dozens of dialects are spoken in Japan. The profusion is due to many factors, including the length of time the Japanese archipelago has been inhabited, the island's mountainous terrain, and Japan's long history of external and internal isolation. Dialects typically differ in terms of pitch stress, inflectional morphology, vocabulary, and particle usage. Some even differ in vowel and consonant inventories, although this is uncommon.

The main distinction in Japanese accents is between Tokyo type (東京式, Tōkyō-shiki) and Kyoto-Osaka type (京阪式, Keihan-shiki). Within each type there are several subdivisions. The Kyoto-Osaka type dialects are found in the central region, roughly made up of the Kansai, Shikoku, and Western Hokuriku regions.

Dialects from peripheral regions, such as Tōhoku or Kagoshima, may be unintelligible to speakers in other parts of the country. There are some linguistic islands in mountain villages or isolated islands, such as Hachijō-jima Island, whose dialects are descended from the Eastern dialect of Old Japanese. The dialects of the Kansai region are spoken or known to many Japanese, with the Osaka dialect in particular being associated with comedy. The Tōhoku and Northern Kantō dialects are associated with typical regional farmers.

Regarding the Ryukyuan languages, which are spoken in Okinawa and the Amami Islands (politically part of Kagoshima), the Japanese government maintains the policy that all Ryukyuan languages are merely "dialects of Japanese", even though they are distinct enough to be considered a separate branch of the Japanese family; not only is every language unintelligible to Japanese speakers, but most are unintelligible to speakers of other Ryukyuan languages. However, in contrast to linguists, many ordinary Japanese tend to regard the Ryukyuan languages as dialects of Japanese. The imperial court also appears to have spoken an unusual variant of Japanese of the time. This is most likely the spoken form of Classical Japanese, a writing style that was prevalent during the Heian period but began to decline in the late from the Meiji era. Ryukyuan languages are spoken by fewer and fewer older people, which is why UNESCO classified them as endangered, as they could become extinct by 2050. Young people mainly use Japanese and cannot understand Ryukyuan languages. Okinawan Japanese (not to be confused with the Okinawan language) is a variant of Standard Japanese influenced by the Ryukyuan languages. It is the main dialect spoken among young people in the Ryūkyū Islands.

Modern Japanese has become widespread throughout the country (including the Ryūkyū Islands) due to education, media, and increased mobility within Japan, as well as economic integration.

Number of speakers by country

History of dialects

Language variants have been confirmed from ancient Japan, through Man'yōshū. The oldest known Japanese writings that include eastern dialects whose features were not inherited by modern dialects except for some parts such as the island of Hachijo.[citation needed]With the With the modernization of Japanese in the late part of the 19th century, the government has promoted the use of Standard Japanese which has made this dialect not only highly known only in Japan but also throughout the world. The language has been changing by merging various dialects and receiving influence from other languages.

Historical variants

The history of the Japanese language is usually divided into four different periods.

- Prehistory: Nothing is known for certain of the language at this time (not even if it existed), due to the lack of documentation or testimony about it.

- Old Japanese: an exact date of dating is still indefinite, although its end is defined around the centuryVIII (conventionally takes the year 794 d.C.), during this period the Chinese writing adapted to write the old Japanese through man'yōgana and the Chinese characters

- Japanese average: from the end of the centuryVIII at the end of the centuryXVI, and shows certain phonetic changes with respect to the previous period, such as phonetic change /p/g/h,./.This has two stages:

- Japanese early: from 794 AD to 1185. Among the most important of this period is the emergence of two new silagic writing systems, the hiragana and the katakana that derive directly from the man'yōgana. This apparition gives rise to a boom in a new era of writing evidenced by writings as Genji Monogatari, Taketori Monogatari e Ise Monogatari.

- Japanese half late: from 1185 to the end of the centuryXVI. In this period the Japanese suffered several linguistic changes that brought him closer to the shape of modern Japanese. In the same way during this period in Japan it evolves from an aristocratic society of nobles to the Heian Period of a feudal nature where the boom of samurai was given. In the middle of the centuryXVI Portuguese missionaries arrive in Japan. As they introduced Eastern concepts and technologies they shared their language, the fruit of this is that the Japanese took some words of Portuguese.

- Modern Japaneseof the centuryXVII Henceforth, characterized by numerous palatalizations of the coronal consonants:

- ♪ yeah, ♪,i,,i/ (shi, ji) /*sya, *syo, *syu; *zya, *zyo, *zyu/negative [,o,,u,,a,,o,,u] (sha, sho, shu; ha, jo, ju).

- [*ti, *di ]t spin ti, d borrow,i] (Chi, ji[*tya, *tyo, *tyu; *dya, *dyo, *dyu ]t spin;a, t spin;o, t hire;u; d book;a, d book,o, d book;u] (cha, cho, chu; ja, jo, ju).

Influences

Some of the lexical similarities between the Austronesian languages and Japanese may be due to the astratic influence of some languages, although the evidence for such prehistoric influence is inconclusive. From the VII century, the influence of Chinese culture in Japan is notorious and the adoption in this language of numerous lexical borrowings from the Chinese language to designate technical and cultural concepts associated with Chinese influence. Classical Chinese is to Japanese, somewhat similar to what roots of Greek origin are to European languages: a source of lexical items to form neologisms. The Japanese writing system itself is itself a sign of Chinese cultural influence on Japanese.

From the 16th century, Japanese will adopt some terms from Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and other languages of European colonization. And from the XX century, the influence of English as a source of new loans to Japanese is hegemonic.

Linguistic description

Phonology

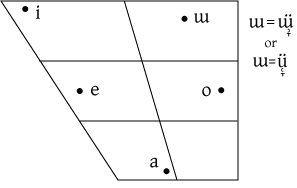

It has five vowels and sixteen consonants and is very restrictive in syllable formation. The accent is tonal, with two different tones: high and low.

The Japanese phonological system consists of five vowels, which written in Latin characters are: a, i, u, e, o, according to the traditional order. They are pronounced the same as in Spanish /a, e, i, o/ except for the u /ɯ/, which is pronounced with the lips extended, that is, it is an unrounded vowel. Vowels can be normal or long, in which case they have double the normal duration and are considered as separate syllables.

There are sixteen or fifteen consonant phonemes, depending on whether or not the sokuon is considered to correspond to a geminate consonant or to the archiphoneme /Q/, represented in writing by the symbol sokuon that takes the same sound as the consonant that follows it or is sometimes pronounced as a glottal stop. The sound count is much higher if consistently occurring allophones, represented in square brackets in the following table, are counted. It should also be considered that borrowings from other languages from the XX century, particularly from English, may retain phonemes foreign to the inventory traditional.

- The consonants /t/, /s/, /d/ and /z/ suffer a palatalization before /i/ and /j/, articultured respectively [t redunda.], [.], [d redunda.] and [.]. Because of this, these sounds are usually transcribed in Latin alphabet as ch, sh and j.

- The consonants /t/ and /d/ ante /./ are pronounced respectively [t savings] and [d flipz]. Because of this, your Latin transcripts in this position are usually ts and [d]z.

- There is a phenomenon called Yotsugana, by which four syllables in principle different (/zi/, /z./, /di/ and /d),/), today can be homophones or two, three or four syllables different according to the region. For example, in Tokyo there are only two: /zi/ and /di/ pronounce indistinctly [.i] or [d redunda͡i], while /z./ and /d./ may be [z.] or [d redundaz.].

- The fonema /h/ has three alophones: before /a, e, o/ would sound like [h], while before /./ would sound [.] and before /i/ and /j/ as [ç].

- Fonema /p/ does not occur in initial position in native or but-Japanese words, although in loans, neologismos and mimetic terms, as in ancient Japanese was given the change /p/ /2005 /./ /h/ in native words.

- The archfonema /// usually sounds like [n], but before /m/ and /b/ it is articulated as [m] and before /g/ and /k/ becomes, a nasal consonant watch. Some speakers nasalize the vowels that precede it.

- Fonema /./ resembles a Castilian ere, but unlike this, it also exists in initial position. It is considered vulgar or rude the multiple vibrant realization, similar to the Spanish erre.

- In some areas of Japan, /g/ is among vowels, but their appearance may be conditioned for some speakers by the fact that they are within a morphism and not as the first element of the second member of a composite word.

- A common phonetic phenomenon in Japanese is the ensorption of the vowels /./ e /i/ (alteration of the sound vocal in murmured vowel due to the context) when they are in a position not accentuated among deaf consonants. It is the case of many terminations of his and Masu in verbal conjugations, which are heard as des des and mass respectively.

- Another particular, frequent and very complex phenomenon is rendaku, which consists of the sounding of a deaf consonant in native composite words: 国 (Country) /kuni/ more,(repetition of the previous element, called Noma,kuma, kurikaeshi or dō no jiten). The /k/deaf of the second kuni becomes its sound counterpart /g/; therefore, it is not pronounced */kunikuni/, as could be expected, but /kuniguni/ which means "country".

- A vowel, like a

- A consonant and a vowel, like ki or Ma

- A semiconsonant and a vowel, like already.

- A consonant, a semiconsonant and a vowel, like kya or nyu

- N (in the end of syllable)

- Q (sokuon)

Grammar

Japanese is an agglutinative language that combines various linguistic elements into single words. Each of these elements has a fixed significance and is capable of existing separately. Japanese is almost exclusively suffixed, with very few prefixes, such as the honorifics o-(お), go- (ご), so the only processes for word formation are composition and suffix derivation. The grammar of the Japanese language is very different from that of Spanish. Some of its features are:

- The grammatical structure is subject-object-verb and postpositions are used instead of prepositions.

- There are no articles, no grammatical gender (male/female), no mandatory number and the case is indicated by clinics.

- The notion of plurality is not widespread. In general, the plurality of the subject or object is not used in the context. However, the suffix -tachiamong others, indicates the idea of plurality (for example, watashi, oriented (Русский, ▸?), [w›wt›]i]] = 'I'; watashi-tachi (associated) (Русский, ?), [wѕwt・ɑi t taxɑt](i)]] = 'we'), and sometimes a word can be duplicated for the same purpose (e.g., from the former first-person pronoun ware,. [wound] margin], formed by duplication - through the sign called kurikaeshi- wareware, ^ [wѕ]のɾ。another extremely formal way of saying 'us'. Doubling kanji forces in some cases to add the brand nigori ((¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü [nji]σoɾγi]]) for example milestone (b) (と dice, .?) [](i)]to]]) = 'person', milestone (b) ( praiseworthy, 人?) [(i)toto]bito]]) = 'persons'.

- There is no future time. Verbal times are the past and the present (the latter also used for actions located in the future). The future is deduced by the presence in the prayer of words as “ashita» ( (Русский, 日本語?) [/25070/(i) t taxes]]) = "morning day."

- The Japanese lacks authentic pronouns, since the forms called "pronouns" always have lexicon content.

- In line with the previous property, verbs are basically impersonal with special forms. Verbal adjectives have only one form.

- From the syntactic point of view Japanese lacks functional categories

- In order to express quantities, so-called numerical sorters (counters) are used, while in Spanish it is sufficient to use the cardinal number followed by the intended object. Thus, for example, to count small animals the counter is used «- Hiki.» (),), for elongated objects (e.g. a pencil) the counter is used «-hon» ([hello]), for machines (including electronic devices) is used «-dai» ([dѕ]i]etc. These sorters can alter their pronunciation according to the number counted (e.g. 1 small animal = ippiki [ippi]ki]], 2 small animals = nihiki [ni]iki]], 3 small animals = sanbiki [s›m]biki]]etc.).

- There are two types of adjectives. The first guy is the "ikeiyōshi» (ה , «ikeiyōshi»?) [i]ke intended for the purpose] ('adjectives in ♪) that end in the vowel i (y) with certain exceptions as “kirei» (▪, ?) [ki] turning], 'lindo', 'bello'), «Kirai» (., い.?) [ki]のɾ], 'odious') and ('yūmei» (., «yūmei»?) [j] meant for me], 'famous'), which belong to the second group despite its completion in 'i' The conjugation of the rogatory changes the «i» end by a disindence that determines verbal time as well as its positive or negative character. For example, an adjective like "Yasui» (., «Yasui»?) [j›ss]i]], 'is cheap'), forms negation with disindence -kunai (expensive), remaining like:alreadykunai» (., «alreadykunai»?) [jѕ]s())k]nѕ]i]]It's not cheap. In the same way, the form in the past time replaces the disindence of "alreadyi»by «alreadykatta» (,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, «alreadykatta»?) [j›ɑs())ɑk›ɑtIt was cheap. As for the negative of the form in the past is replaced i at the end of disindence kunai for katta, coming up kunakatta "alreadykunakatta» (¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü , «alreadykunakatta»?)) [jŭs(ɑ))k]n bookkeeperɑttIt wasn't cheap, 'it wasn't cheap.' A model is thus created: alreadyi - alreadykatta - alreadykunai - alreadykunakatta. Noting the formation of the negative past time of these adjectives, there is a feature of the agglutinating character of the Japanese: the -kunai disindence, at the end of -i, becomes a new adjective, which can be conjugated to the last time -kunakatta.

- The other type of adjective is called “nakeiyōshi» (▪, «nakeiyōshi»?) [n›]ke intended for the purpose] ('adjectives in na'). To attach them to a noun the particle is required na (plus) (then its name), unlike the previous ones that can be used without any particles together with a noun. The «nakeiyōshi» do not usually end in «i» except exceptions as already mentioned (kirei, Kirai, yūmeiand others). The conjugation uses the termination that indicates whether it is positive or negative as well as its temporality. For example:shizuka» (・, «shizuka»?) [gili]z]k tax]], 'quick'), to indicate his negative we adhere to the "ja arimasen» (أعربية, «ja arimasen»?) [d]›] ♡i]mase]N] in informal register or «dewa arimasen» (♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫, «dewa arimasen»?) [de]w diagnosis ₡ ɑmase]N] In formal registration, a kind of 'is not'. Note: ・.。 Qualified handwriting(Ja arimasen) & 。¶ Quote random。 (dewa arimasen) can be uttered 。.。 Quote。 (Ja arimahen) & 。 Quote? y 。 Examples of adjectives ikeiyōshi and nakeiyōshi: Positive

- Русский polling.日本語

- ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫ ♫.。od read

- Kyō wa atsui hi desu.

- 'Today is a hot day'.

- Lessons Learn more.▪

- Lessons Learn more.。щатарики

- Misae-san wa kireina His milestone.

- 'Mrs. Misae is a beautiful person.' Negative

- ▪ boundless innovation..

- أعر مع مع من مع مع مع مع من مع من مع مامن..

- Kono hon wa sonna ni takakunai desu.

- 'This book is not so expensive.' Note: If you want to sound informal, . desu (verb being or being) must be changed by . (da).

Writing

- The first is composed of Chinese ideograms, or kanjiintroduced in Japan around the fourth century. These are used as ideograms and phenograms. Each kanji has various readings, both native and Chinese root. (Sometimes it only has a type of reading as well as some kanjis have multiple readings of each type). Usually, Chinese reading is used when composite words are formed (2 or more kanjis together) and native reading is used in 'solitary' kanjis. Chinese reading is referred to as מ).(On-yomi) and native or Japanese reading).の). or also ה-(Kun-yomi). For example: The Kanji Русский'agua') has 2 readings: the reading Kun).tres (mizu) and the reading On lice (sui). The Kanji El('dog') has 2 readings: the Kun rica lectura (inu) reading and the On /25070/ (ken).

- The second system is called kana and was developed about 500 years after kanji. They belong to kana two forms of writing that are own links, the Hiragan and katakana. The first, serves to write all other words of Japanese origin or in the absence of kanji and, when these are present, it is used to indicate disinsencies. The second, is used to write intersections, "onomatopeyas" and recent entry loans to the language, has its origin in the beginnings of the Heian era (794–1185), having as first use being a help in reading the characters of the sutras, the Buddhist writings, being in their time, more popular than the Hiragana, not becoming this other common war. In Japanese the so-called "unlucky sounds"(b, d, g, z) are formed by adding a brand called "ten ten" or nigori (り り ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü) which consists of two lines at the upper right end in vertical form, to the character of the corresponding "pure sound" (in h, t, k, srespectively). The characters in p (“mid impure sound”) are formed by adding characters in h a mark similar to a small circle, called maru. Examples of "ten ten" or nigori:,,,,,,,,,, nigori: gi, go, ge, gu and ga respectively nigori: ki, ko, ke, ku, ka) Examples of maru,,,,,,,,,,, maru: pi, po, pe, pu, pa maru: hi, ho, he, fu, ha) Due to phonetic reasons called rendaku ona few words can change a pure original sound by an impure one (e.g.: consuming chanting, “kaimonobukuro” (“buying bag” in opposition to kaimono fukuro). In addition, a final "chi" or "tsu" can make a word come together with the following, bending the initial consonant sound of it. For example, ichi + ka → ikka. The double consonant, in writing, comes preceded by a small character tsu.

Contenido relacionado

The great Carlemany

Annex: World Heritage in Peru

Arabian language