Islamic art

By Islamic art is known the artistic style developed in the culture generated by the Islamic religion.

Islamic art has a certain stylistic unity, due to the displacement of artists, merchants, patrons and workers. The use of a common script throughout the Islamic world and the development of calligraphy reinforce this idea of unity. They attached great importance to geometry and decoration, which could be of three types:

- Cuffic calligraphy: by verses of the Quran.

- Laceria: through interwoven lines forming stars or polygons.

- Ataurique: by plant drawings.

In architecture, they created buildings with specific functions such as mosques and madrasahs, following the same basic pattern, albeit with different shapes. There is practically no art of sculpture, but the realizations of metal, ivory or ceramic objects frequently reach a high technical perfection. There is also a painting and an illumination in the sacred and profane books.

Characterization

Islamic art is sometimes mistakenly referred to as Arabic art as well. This error comes from an inaccurate use of its meaning, since of the two meanings of the Arabic term, one is geographical, applicable to the natives of Arabia, while the other is linguistic, referring to those who speak the Arabic language of their culture. Muslim art or Islamic art from the Iberian Peninsula is known as Hispano-Muslim art.

Islam

The Islamic era, Hegira, begins in the year 622, the date on which Muhammad marches from Mecca to Medina fleeing from the intransigence shown by his preaching. From that date, along with religious faith, new social and political attitudes arose that, in less than a century, spread from the Bay of Bengal to the Atlantic Ocean.

Islam ('peace, through loving obedience to God') has as its spiritual (or metaphysical) basis a holy book, called the Koran, which contains the word of Allah (God), revealed directly to Muhammad, the last messenger of Islam, throughout his life, through small verses. The communication of the divine message was carried out in the Arabic language (because, in those times, the Arab people were one of the most noble, honest and sincere peoples on the face of the Earth. However, the divine message was already had sent to other peoples and in other languages, before the Arab people, such as the Torah for the Jewish people and the Bible for the Christian people), after which it became the official language and the vehicle of unity.

In addition to the Koran, there is another primordial source known as sunna (custom, habit or manner), related to the figure of the prophet The sunna is configured based on hadith or set of acts or sayings of Muhammad, constituting an authentic science of tradition.

Every Muslim (muslim) has to carry out five manifestations or acts in which the dogmatic content of the religion and its aspects of worship or rite are basically collected. They are known as the pillars of Islam: profession of faith, prayer, almsgiving, fasting and pilgrimage to Mecca. Each of them has a special impact on artistic expressions. The profession of faith or sahada (there is no God but God and Muhammad his prophet) makes explicit the non-existence of the concept of incarnation of Christianity and Hinduism, at the same time that it proclaims that Muhammad is only the messenger of God. This entails the primacy of the message over the messenger, in the same way that it is, without a doubt, the key to the development that writing acquires as a decorative motif - epigraphy - within Islamic art. It reflects, at the same time, the aniconic tendency latent in Islam from the first moments, although, not for this reason, figuration ceased to have a certain presence, albeit in restricted areas. This aniconic trend will lead to the great development of geometric and vegetal motifs with an increasing degree of abstraction that, together with the epigraphic ones, will define the ornamentation in Islamic art.

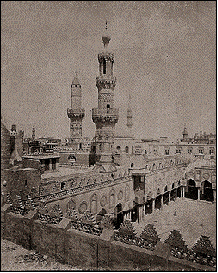

Prayer or salat is the precept according to which Muslims must pray regularly five times a day. This requires a state of ritual cleanliness or ablutions, sufficient space to prostrate and bow the head to the ground, and a correct orientation towards Mecca. A consequence of these obligations is the existence of a building, the mosque (masjid or place to prostrate oneself) with a qibla wall where the mihrab or niche is located. i> that indicates the correct orientation to Mecca. Mosques usually have a courtyard (sahn) in which there is a fountain (mida) for ablutions or body cleansing. Other associated elements are the minbar or kind of pulpit with steps for the jutba (Friday sermon), the maqsura or boundary for the authorities, the minaret (manara) from whose roof the muezzin calls to prayer and they also use the prayer rugs (sayyada) for greater cleanliness in the development of the sentence.

The obligation to give alms (zakat) produces in the artistic field the foundation of charitable institutions such as madrasas or theological schools where the Koran is taught, maristan or hospitals, hamman or baths and public fountains. Fasting (sawn) during the month of Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic lunar calendar, has less artistic significance, although it can take the form of certain objects made for the festivals of breaking the fast held at the end of Ramadan.

The last precept, the pilgrimage to Mecca (hayy), at least once in a lifetime, allows the exchange of ideas between the most distant countries, the production of special works such as cloths that the caliph sends annually to cover the Kaaba or the ornamental certificates of the pilgrimage.

Religion, then, constitutes the great unifying element of the wide territory and the extensive time frame -VII century to today - by which Islam has spread. However, this space-time development has generated an enormous variety of artistic manifestations. Logically, geographical conditions -from deserts to plateau or mountainous areas- as well as historical factors and the consequent pre-existing civilization substrates in each cultural area have had a decisive impact on artistic expressions, determining their different evolution and their different peculiarities. However, these conditions and the assimilation of traits from all those cultures with which it has been in contact, has not led Islamic art to become a mere repetition of foreign forms and elements. On the contrary, by selecting from a vast repertoire and using it appropriately to its different function, he has achieved a profoundly original art.

History of Islamic art

The beginnings of Islamic art (7th to 9th centuries)

Before the dynasties

Little is known about the architecture before the Umayyad dynasty. The first and most important Islamic building is undoubtedly the house of the Prophet in Medina. This more or less mythical house was the first place where Muslims gathered to pray, although the Muslim religion believes that prayer can be done anywhere.

The house of the Prophet was of great importance for Islamic architecture, since it establishes the prototype of the mosque of Arab design, formed by a courtyard with a hypostyle prayer room. This model, adapted to prayer, was not born out of nowhere, it could be inspired by the Husa temple (Yemen, II century BC) or by the Dura Europos Synagogue (renovated in 245). Built with perishable materials (wood and clay), the Prophet's house did not survive for long, but it is described in detail in Arabic sources. Currently, the Mosque of the Prophet stands on the place where the house of Muhammad was supposedly located.

Early Islamic objects are very difficult to distinguish from objects from earlier Sasanian and Byzantine, or already Umayyad, eras. In fact, Islam was indeed born in areas where art seems to have been scarce, but surrounded by empires notable for their artistic production. That is why, in the beginnings of Islam, Islamic artists used the same techniques and the same motifs as their neighbors. An abundant production of dull ceramics is known, especially, as evidenced by a famous bowl that is preserved in the Louvre Museum, whose inscription assures us that its manufacture dates back to Islamic times. The bowl comes from one of the few archaeological sites that traces the transition between the pre-Islamic world and Islam: Susa in Iran.

Umayyad art

Among the Umayyads, religious and civil architecture grew with the introduction of new concepts and designs. In this way, the Arab plan, with a courtyard and a hypostyle prayer room, becomes a model plan based on the construction of the most sacred place in the city of Damascus - in the ancient temple of Jupiter and in the place where was the Basilica of San Juan Bautista - of the Great Mosque of the Umayyads. The building was an important landmark for the builders (and art historians) to locate the birth of the Moorish plan there. However, recent work by Myriam Rosen-Ayalon suggests that the Arab plan was born a little earlier, with the first project to build the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem is undoubtedly one of the most important buildings in all Islamic architecture, characterized by a strong Byzantine influence (mosaics with a gold background, centered plane reminiscent of the Holy Sepulchre), but which already has purely Islamic elements, such as the large frieze with religious inscriptions from the Koran. Its model did not spread, and what Oleg Grabar considers the first monument that was a great aesthetic creation of Islam, was left without posterity.

The Castles of the desert in Palestine offer us a lot of information about the civil and military architecture of the time, although their exact function is still under study: stop for caravans, resting places, fortified residences, palaces for political purposes that allowed the meeting between the caliph and the nomadic tribes? Specialists strive to discover it, and it seems that its use has varied depending on the place where they are located. Anjar was a complete found city and it tells us about a type of urbanism still very close to that of ancient Rome, with thistle and decumanus, as in Ramla.

In addition to architecture, artisans worked ceramics, often unglazed, sometimes with a transparent, green or yellow monochrome glaze, and also worked metal. It is still very difficult to differentiate these objects from those of the pre-Islamic period, the artisans reused Western elements (vegetable foliage, acanthus leaves, etc.) and Sassanids.

In architecture as in the furniture arts, the Umayyad artists and craftsmen did not invent new forms or methods, but spontaneously reused those of the Mediterranean and Iranian Late Antiquity and adapted them to their artistic design, for example, through the substitution in the great mosque of Damascus of the figurative elements that the Byzantine mosaics had, by drawings of trees and cities. In the desert castles these borrowings and adaptations are reflected in particular. The mixture of tradition and readaptation of motifs and architectural elements gradually created a typically Muslim art, palpable above all in the aesthetics of the arabesques, present at the same time as in the monuments in the objects or on the pages. from the illuminated Qur'ans.

Abbasid art

With the displacement of the centers of power to the east, two cities that would successively be capitals of the caliphate became very important: Baghdad and Samarra in Iraq. The city of Baghdad could not be excavated because it is covered by the contemporary city. We know it from various sources, which describe it as a circular city in whose center great mosques and palaces were built. Samarra has been the subject of several excavations, notably by Ernst Herzfeld and more recently by Alastair Northedge. Created by Al-Mutasim, in the year 836, it covers about thirty kilometers 2, and also had many palaces, two large mosques and several barracks. Definitely abandoned at the death of Al-Mu'tamid in the year 892, it offers us a reliable chronological milestone.

Samarra has provided us with a large amount of furniture, especially stucco which served as architectural decoration and whose motifs can serve for the approximate dating of the buildings. Stucco is also found in furniture art from Tulunid Egypt to Iran, especially accompanying wood in decoration.

The art of ceramics experienced at least two great innovations: the invention of faience and ceramics with a metallic luster that will last long after they have disappeared. of the dynasty. In Islam, a mass of clay paste is called faience, covered with an opaque enamel treated with tin oxide, and decorated. Imitations of Chinese porcelain multiplied then thanks to cobalt oxide, used since the VIII century in Suse, and which allows decorated in blue and white. The repertoire of motifs is still quite limited: plant motifs and inscriptions.

The metallic luster was born in the IX century, perhaps due to the incorporation of an existing product into ceramics and that it was used in glass. The chronology of this invention and of the first centuries is very difficult and has given rise to many controversies. The first metallic shines would be polychrome, without images and from the X century they would become figurative and monochrome, if we are to believe the most commonly accepted opinion, which is based, in part, on the mihrab of the Kairouan Mosque. Transparent or opaque glass was also produced, decorated by blowing into a mold or by adding other elements. There are several examples of glass carving, the most famous being probably the bowl of hares, which It is preserved in the Treasury of San Marcos in Venice, and the architectural decoration in this material that has been found in Samarra.

Medieval times (9th – 15th century)

Since the IX century, the power of the Abbasid dynasty has been challenged in the provinces furthest from the center of Iraq. The creation of a rival Shiite caliphate, the caliphate of the Fatimid dynasty, followed by the Umayyad caliphate of Spain, fleshed out this opposition. Small dynasties of autonomous rulers also appeared in Iran.

Spain and the Maghreb

The first dynasty to settle in the Iberian Peninsula (in al-Andalus) was that of the Umayyads of Spain. As its name suggests, this lineage descends from that of the great Umayyads of Syria, decimated in the IX century. The Umayyad dynasty in Spain was replaced after its fall by various independent kingdoms, the Taifa kings (1031 - 1091), but the artistic production in this period did not differ much after this political change. At the end of the XI century, two Berber tribes successively seized power in the Maghreb and in Spain, then in full Reconquista, the Almoravids and the Almohads of North Africa, who brought their North African influence to art.

However, the Christian kings gradually conquered Islamic Spain, which was reduced to the city of Granada in the 14th century with the Nasrid dynasty, which managed to maintain itself until 1492.

In the Maghreb, the Marinids took the torch from the Almohads in 1196. From their capital Fez they participated in many military expeditions, both in Spain and Tunisia, from where they could not dislodge the Hafsids, a small dynasty firmly established over there. The Marinids saw their power diminish from the 15th century and were finally replaced by the Sharifs dynasty in 1549. The Hafsides dynasty ruled until their eviction by the Ottoman Turks in 1574.

Al-Andalus was a place of great culture in medieval times. In addition to important universities such as Averroes, which allowed the spread of philosophy and science unknown to the Western world, this territory was also a place where art flourished. In architecture, the importance of the Great Mosque of Córdoba is evident, but this should not overshadow other achievements such as the Bab al-Mardum mosque in Toledo or the caliphal city of Medina Azahara. The Alhambra palace in Granada is also especially important. Several features characterize the architecture of Spain: horseshoe arches derived from Roman and Visigoth models. Polylobed arches, very common and typical of the entire Islamic period. The shape of the mihrab, like a small room, is also quite a characteristic feature of Spain.

Among the techniques they used to make objects, ivory was widely used to make boxes and chests. The Al-Mughira Pyx is a masterpiece, with many figurative scenes and difficult to interpret.

Fabrics, silks in particular, were mostly exported and can be found in many Western church treasuries wrapping the bones of saints. In ceramics, traditional techniques, especially the metallic luster, which was used in the tiles or in a series of vases known as Alhambra vases. From the reign of the Maghrebi dynasties, there was also a taste for woodworking, carving and painting: the Minbar of the Kutubiyya Mosque in Marrakech, dating from 1137, is one of the best examples.

North African architecture is relatively unknown due to lack of research after decolonization. The Almoravid and Almohad dynasties are characterized by a search for austerity that is exemplified in the mosques with bare walls. The Merinid and Hafsid dynasties patronized very important but little-known architecture and remarkable painted, carved, and inlaid woodwork.

Egypt and Syria

The Fatimid dynasty, which is one of the few dynasties in the Shia Islamic world, ruled Egypt between 909 and 1171. Born in Ifriqiya in 909, it came to Egypt in 969, where it founded the Caliphate city of El Cairo, north of Fustat, which remained an important economic center. This dynasty gave birth to important religious and secular architecture, the remains of which include the al-Azhar and al-Hakim mosques, and the walls of Cairo, built by the vizier al-Badr Jamali. It was also the origin of a rich production of art objects in a wide range of materials: wood, ivory, ceramics painted with brilliant enamel, silver, metal inlays, opaque glass, and above all, rock crystal. Many artists were Coptic Christians, as evidenced by the many works with Christian iconography. These constituted the majority religion during the particularly tolerant reign of the Fatimids. The art is characterized by a rich iconography, which greatly exploits the human and animal figure in animated representations, which tends to free itself from purely decorative elements, such as color spots on glazed ceramics. He was enriched, both stylistically and technically, through his contacts with the cultures of the Mediterranean basin, especially Byzantium. The Fatimid dynasty was also the only one to produce sculpture, often in bronze.

At the same time, in Syria, the atabegs, that is, the Arab governors of the Seljuk princes, came to power. Very independent, they relied on the enmity between the Turkish princes and largely helped the Frankish crusaders. In 1171, Saladin seized Fatimid Egypt, placing the short-lived Ayyubid dynasty on the throne. This period was not very rich in architecture, which did not prevent the renovation and improvement of the defenses of the city of Cairo. The production of valuables did not stop. Pottery painted with bright enamels and inlaid with high-quality metal continued to be produced, and enameled glass emerged from the last quarter of the century XII, as seen on a series of glasses and bottles from this period.

The Mamluks seized power from the Ayyubids in Egypt in 1250 and settled in Syria in 1261, defeating the Mongols. They are not, strictly speaking, a dynasty, because the rulers do not rule from father to son: in fact, the Mamluks are freed Turkish slaves, who (in theory) share power between fellow freedmen. This paradoxical government lasted almost three centuries, until 1517, and gave rise to an architecture very abundant in stone, made up of large complexes made for the sultans or emirs, especially in Cairo. The decoration is made with inlaid stones of different colors, as well as exquisite woodwork that consisted of inlaid radiant geometric motifs made in marquetry. Enamel and glass were also used, and what is more important, metal inlays: the Baptistery of Saint Louis dates from this period, one of the most famous Islamic objects, made by the smith Muhammad ibn al-Zayn.

Iran and Central Asia

The Il-khanids

Under these little khans, originally subject to Emperor Yuan but quickly becoming independent, a rich civilization developed. Architectural activity intensified as the Mongols became sedentary and continued to be more or less marked by the traditions of the nomads, as evidenced by the north-south orientation of the buildings. However, there is significant Persian and a return to already established traditions, such as the Iranian plane. Oldjaïtou's tomb in Sultaniya was one of the most impressive monuments in Iran, but sadly it is badly damaged and almost destroyed. Also, during that dynasty, the art of the Persian book was born, in important manuscripts such as the Jami al-tawarikh ordered by the vizier Rashid al-Din.

New techniques appeared in ceramics, such as that of lajvardina, and Chinese influences are seen in all the arts.

The Golden Horde

The art of these nomads is little known. Researchers, who are just beginning to take an interest in them, have discovered that there was urban planning and architecture in these regions. An important goldsmithing was also developed and most of its works show a strong Chinese influence. Preserved in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, they are just beginning to be studied.

It was the third invasion of the nomads, that of Tamerlane's troops, which founded the third great Iranian medieval period: that of the Timurids. The development in the 15th century of this dynasty, gave rise to the apex of Persian book art, with painters such as Behzad, and many patrons. Persian architecture and urbanism, through monuments like those of Samarkand in particular, also experienced a golden age. The ceramic decoration and the muqarnas vaults are particularly impressive. There is a strong influence of the art of the book and China in all other areas. It is, in part, the Timurid period that gave Persian art cohesion, allowing it to flourish later in the great empire of the Sephavids.

Anatolian

Continuing their momentum, the Seljuk Turks continued their conquests as far as Anatolia. After the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 they formed a sultanate independent from that of their Iranian cousins. Their power seems to extend from 1243 to the Mongol invasions, but coins continued to be minted with their names until 1304. The architecture and objects synthesize the different styles of both Iran and Syria. The art of woodworking yields masterpieces, and we know of only one illustrated manuscript dating from that period.

The Turkmeks, who are nomadic in the Lake Van region, are little known. They are known, however, several mosques such as the Blue Mosque of Tabriz and they will have a decisive influence both in Anatolia, after the fall of the Seldjoukidas of Rum, and in Iran during the Timurid dynasty. Indeed, from the 13th century, Anatolia was dominated by small Turkmen dynasties, who gradually decided to appropriate Byzantine territories. Little by little a dynasty arose: that of the Ottomans, the so-called "first Ottomans" before 1453. They sponsored architecture above all, where the unification of spaces is sought through the use of domes. Ceramics also laid the foundation for what would become Ottoman art proper with Miletus pottery and early Anatolian blues and whites.

Indian

India, conquered by the Gaznávidas and Gúridas in the IX century, did not become independent until 1206 when the Muizzî, or slave-kings, came to power, marking the birth of the Delhi Sultanate. Later, other competing sultanates arose in Bengal, Kashmir, Gujarat, Jawnpur, Malwa and in the northern Deccan (Bahmanids).

They gradually moved away from Persian traditions, giving birth to original architecture and urbanism tinged with syncretism with Hindu art. The production of objects is little studied until now, but we know of an important art of the book. The period of the sultanates ends with the arrival of the Mughals who gradually conquered the entire region.

Islamic Art Techniques

Urban planning, architecture and decoration

Architecture takes many different forms in the Islamic world, often its relationship with the Muslim religion: the mosque is one of them, but the madrasa and places of retreat are also typical buildings of Islamic countries adapted to the cult practice.

Building types vary widely across periods and regions. Before the 13th century, in the cradle of the Arab world, that is, in Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Turkey, almost all the mosques follow the so-called Arabic plan, with a large courtyard and a hypostyle prayer hall, but they vary enormously in their decoration and even in their forms: in the Maghreb the mosques adopted a "T" plane with ships perpendicular to the qibla, while in Egypt and Syria the ships are parallel. Iran has its own specificities such as the use of brick and stucco and ceramic decoration, the use of particular forms often borrowed from Sasanian art such as Iwan (entrance porches opened by a large arch) and the Persian arch. In Spain, there is more of a taste for colored architecture with the use of varied arches (horseshoe, polylobed, etc.). In Anatolia, under the influence of Byzantine architecture, but also due to Specific developments in the Arab plan in this region, the great Ottoman mosques with singular and disproportionate domes were built. In Mughal India the plans gradually moved away from the Iranian model, with the bulbous dome being prominent in its buildings.

The art of the book

The art of the book includes both painting, binding, calligraphy and lighting. That is, arabesques and drawings in the margins and in the titles.

The art of the book is traditionally divided into three distinct domains: Arabic for Syrian, Egyptian, Jezirah, and even Ottoman Maghgreb manuscripts (but these can also be considered separately). Persian for manuscripts created in Iran, particularly during the Mongolian period. Indian for Mughal works. Each of these fields has its own style, divided into different schools, with their own artists and conventions. The evolutions are parallel, although it seems evident that there have been influences between schools, and even between geographical areas, through political changes and the frequent displacements of artists.

The so-called « minor » arts

The decorative arts are known in Europe as minor arts. However, in the lands of Islam, as in many non-European or ancient cultures, these arts have been widely used for artistic rather than utilitarian purposes and have reached such a point of perfection that they cannot be classified as crafts. Thus, if Islamic artists were not interested in sculpture for primarily religious reasons, they left us evidence of remarkable ingenuity and mastery in the arts of metal, ceramics, glass, and glass of rock; and also in hard stones such as chalcedony, wood carving, marquetry and ivory,

Motifs, themes and iconography of Islamic art

When the term Islamic art is mentioned, one often thinks of imageless art made up entirely of geometric and arabesque motifs. However, there are many representations of figures in the arts of Islam, particularly in everything that does not fall within the realm of religion.

Art and religion

Religions have played an important role in the development of Islamic art, which has often been used for sacred purposes. One thinks, of course, of the Muslim religion. However, the Islamic world did not have a Muslim majority until the 13th century and other beliefs have also played an important role in the Islam. Christianity, particularly, in an area from Egypt to present-day Turkey. Zoroastrianism, especially in the Iranian world. Hinduism and Buddhism in the Indian world and animism throughout the Maghreb.

Art and Literature

Not all Islamic art is religious, however, and artists used other sources as well, including literature. Persian literature, such as the Shahname , the national epic composed at the beginning of the 10th century by the Persian poet Ferdousí, the Five Poems or Hamsé of Nezamí in the (XII), is also an important source of inspiration for many motifs found in both book art as in objects (ceramics, tapestries, etc). The works of the mystical poets Saadi and Djami have also given rise to many representations. The al-Jami tawarikh , or Universal History, composed by the Ilkani vizier Rashid al-Din at the turn of the century XIV has been the inspiration for numerous performances throughout the Islamic world.

Arabic literature is not the only one with representations; the fables of Indian origin Calila and Dimna or the Maqamat of Al-Hariri and other texts were frequently illustrated in workshops in Baghdad or Syria.

Scientific literature, such as treatises on astronomy or mechanics, also have illustrations.

Abstract motifs and calligraphy

Decorative motifs are very numerous in this art and very varied, from geometric motifs to arabesques. Calligraphy in the lands of Islam is considered an art, even sacred, considering that the suras of the Koran are considered as divine words and that the representations of living beings are excluded from religious books and places, calligraphy deserves a special attention, not only in the religious sphere, but also in profane works.

Figurative representations

Islamic art is often thought to be totally aniconic, yet numerous human and animal figures can be seen on ceramics. The religious images of the Prophet Muhammad, of Jesus and of the Old Testament as well as of the imams, also gave rise to representations that, depending on the time and place, have their faces veiled or not. The question of figurative representation in Islam is still very complex today.

Knowledge of the arts of Islam in the world

Historiography of Islamic art

Islamic art has long been known in Europe thanks to the many imports of precious materials (silk, rock crystal), which were made in medieval times. Many of these objects have become relics and are now kept in the church treasuries of the Western world. However, the history of Islamic art as a science is a very recent discipline compared, for example, with that of other ancient arts. On the other hand, excavations of Islamic art have often fallen victim to archaeologists who, eager to quickly access the oldest levels, looted the most modern levels.

Born in the 19th century and promoted by the orientalist movement, this discipline evolved marked by many fluctuations, due to events world politicians and religions. Colonization, in particular, encouraged the study of some countries - as well as the appearance of European and American collections - but entire periods of history have been forgotten. Similarly, the Cold War has considerably slowed down the study of arts of Islam, preventing the dissemination of studies and discoveries.

Large collections of Islamic art

As is often the case, the great collections of Islamic art are rather in the Western world, at the Louvre Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in particular. However, there are collections elsewhere, including the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo, Egypt, or the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar. The Gulbenkian Lisbon Foundation and the Khalili collection also keep numerous pieces. American museums, such as the Freer Gallery in Washington, have very important collections, both of objects and of manuscripts. The Corning Museum of Glass in New York has one of the largest collections of Islamic glass in the world. As for the manuscripts, we have to point out large libraries such as the British Library or the National Library of France, whose oriental collections are quite complete, although the museums also keep illustrated pages and manuscripts.

Great archaeological sites of Islamic art

Much progress is being made in the study of the production of objects and of the oldest Islamic architecture, especially in Iraq, Samarra or Susa or even in Cairo. Despite the current context, the main sites are being excavated throughout the Islamic world from Pakistan to the Maghreb.

Contenido relacionado

Mansard

United States painting

Mirandés (Asturleone from Tierra de Miranda)