Invasion of grenada

The invasion of Grenada, a military conflict codenamed Operation Urgent Fury (Operation Urgent Fury), was an invasion of the island nation of Grenada by the United States and several other Caribbean nations in response to the coup perpetrated by Hudson Austin and his Soviet-Cuban military alliance. On October 25, 1983, the United States, Barbados, Jamaica, and members of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States landed troops in Grenada, defeated Grenadian and Cuban resistance, and overthrew the military government of Hudson Austin.

Background

On March 13, 1979, a bloodless coup, led by Maurice Bishop, the leader of the New Jewel Movement, overthrew the government of Eric Gairy to establish a government that was accused of espousing Marxism-Leninism and aligning itself with with the Soviet Union and Cuba. Bishop's government was accused of promoting the militarization of his country, which maintained a small army. The government also began building an international airport with the help of Cuba that was disproportionately large for commercial flight use.[citation needed] United States President Ronald Reagan pointed to this airport and several other sites as evidence of Grenada's potential threat to the United States. The US government accused Grenada of building facilities to aid Soviet-Cuban militarization in the Caribbean, and of assisting Soviet and Cuban transport of weapons to Central American insurgents. However, the Bishop government claimed that the airport was being built to accommodate commercial planes carrying tourists.

On October 19, 1983, a socialist faction led by Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard removed Bishop from power; Coard's forces subsequently executed Bishop despite massive protests in his favor. Hudson Austin proclaimed himself prime minister with the support of Coard and his allies. The Governor General of Grenada, Paul Scoon, was placed under house arrest.

The Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) has asked the United States, Barbados and Jamaica for help. According to Mythu Sivapalan of the New York Times (October 19, 1983), this formal appeal was at the behest of the US government, which had decided to take military action against the Austin and Coard regime. US officials cited the coup and general political instability in a country near their own borders as the reasons for the military action, as well as the presence of US medical students at Grenada's St. George's University. Sivapalan also expounded that the latter reason was cited to gain public support, rather than as a legitimate reason for the invasion, since fewer than 600 of the 1,000 non-Grenadian civilians on the island were from the United States: US Congressmen later challenged this argument as false (see below).

«Both Cuba and Grenada, when they saw that U.S. ships were heading towards Grenada, sent urgent messages promising that U.S. students were healthy and urged that an invasion should not occur. [...] There is no indication that the administration made a determined effort to evacuate Americans peacefully. [...] Officials have acknowledged that there was no attempt to negotiate with the granadinas authorities.»

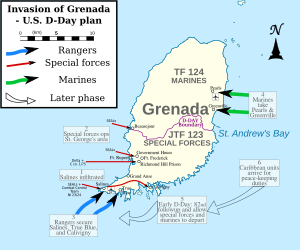

The invasion

The invasion, which began at 05:00 on October 25 (two days after the serious attacks in Beirut), was the first major operation carried out by the United States military since the Vietnam War. Fighting continued for several days and the total number of American troops reached about 7,000 along with 300 OECS men. The invading forces found some 1,500 Grenadian soldiers and some 700 Cubans, most of whom were construction workers. Yet some of these "construction workers" According to the Americans, they were supposedly detachments of the Cuban special forces and military engineers.

Official US sources state that the defenders were well prepared, well positioned and put up strong resistance, to such an extent that the US had to call in two battalions of reinforcements on the afternoon of October 26 from the SEALS, which received casualties due to resistance. Nonetheless, the invading forces' total naval and air superiority and readiness — including attack helicopters and supporting naval artillery — proved to be significant advantages against the Grenadian and Cuban soldiers.

US forces suffered 19 fatalities and 116 injuries. Grenada suffered 45 military deaths and also at least 24 civilians, along with 358 wounded soldiers. Cuba had 25 killed in action, with 59 wounded and 638 taken prisoner.

Reaction in the United States

A month after the invasion, Time magazine described it as having garnered broad popular support. A congressional think tank concluded that the invasion had been justified, as many members felt that the students could be taken hostage just like US diplomats in Iran four years ago. The group's report caused O'Neil to change his position on the matter, from opposing to supporting it. Taken together, the invasion produced a sense of military pride in the American public.

However, some members of the study group disagreed with his conclusions. Congressman Louis Stokes claimed that "Not a single American child nor a single American citizen was in any way endangered or held hostage prior to the invasion. The black cabal in Congress denounced the invasion, and seven House Democrats, led by Ted Weiss, attempted to impeach Reagan.

International opposition and criticism

Grenada was part of the British Commonwealth of Nations and — after the invasion — turned to other members of the Commonwealth for help. The United Kingdom and Canada, among others, opposed the invasion. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher personally opposed the American invasion, and her Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe announced to the House of Commons the day before the invasion he had no knowledge of any possible intervention by the United States. Ronald Reagan, President of the United States, assured him that an invasion was not contemplated. Reagan later said:

She was very firm and continued to insist that we cancel our landing in Granada. I couldn't tell him he'd already started.

After the invasion, Prime Minister Thatcher wrote to President Reagan:

This action will be seen as an intervention by a Western country in the internal affairs of a small independent nation, as much as we dislike its regime. I ask you to consider this in the context of our extensive Eastern-Western relations and the fact that we will have in the coming days to present our Parliament and the people of the site of the cruise missiles in this country... I can't hide that I'm deeply concerned about your last statement.

The invasion of Grenada is frequently exposed as a case of application by the United States of the so-called National Security Doctrine.

Consequences

Following the US victory, Grenada Governor-General Paul Scoon appointed a new government, and in mid-December US forces withdrew.

The invasion revealed problems with the US government's "information apparatus," which The New York Times described as still "a bit of a mess" three weeks after the invasion. For example, the United States Department of State falsely claimed about the alleged discovery of a large mass grave containing the corpses of about 100 islanders, who were said to have been killed by communist forces.

The problems in the army that the invasion demonstrated also caused great concern. There was a lack of information on Grenada, which compounded the difficulties faced by the hastily assembled invasion force. For example, it was not reported that the students were actually on two different campuses, and that there was a thirty-hour delay in rescuing the students on the second campus. Analysis issued by the United States Department of Defense demonstrated the need for improvements. communications and coordination between the different branches of the Armed Forces. Some of these recommendations resulted in the formation of the United States Special Operations Command in 1987.[citation needed]

Order of Battle

United States Forces and Allied Ground Forces

- United States

- 22.a Marines Expeditionary Unit

- 82.a Airborne Division

- 75.o Ranger Regiment

- SEAL 5 and 6

- Delta Force

- 160.o Special Operations Aviation Regiment

United States Naval Forces

Amphibious Squadron Four

- USS Guam

- USS Barnstable County

- USS Manitowoc

- USS Fort Snelling

- USS Trenton

Independent Task Group

- USS Independence

- USS Richmond K. Turner

- USS Coontz

- USS Caron

- USS Moosbrugger

- USS Clifton Sprague

- USS Suribachi

In addition, the following vessels supported naval operations:

- USS America

- USS Aquila.

- USS Aubrey Fitch

- USS Briscoe

- USS Portsmouth

- USS Recovery

- USS Saipan

- USS Sampson

- USS Samuel Eliot Morison

- USS Taurus