International Workers' Day

The International Workers' Day or May Day is the commemoration of the world labor movement. It is a day that has been used habitually to carry out different social and labor demands in favor of the working classes by, fundamentally, the anarchist and communist movements, among others. It is a national holiday in most countries of the world.

Since its establishment in most countries (although the consideration of the holiday was in many cases late) by agreement of the Socialist Workers Congress of the Second International, held in Paris in 1889, it is a day of struggle for demands and homage to the Chicago Martyrs. These anarchist syndicalists were executed in the United States for participating in the protests fighting for the achievement of the eight-hour working day, which originated in the strike that began on May 1, 1886 and reached its peak three days later, on May 4, in the Haymarket Riot. From then on it became a day to demand the rights of workers in a general sense that is commemorated to a greater or lesser extent throughout the world.

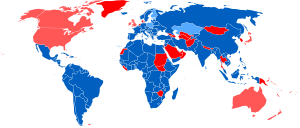

In the United States, Canada and other countries, this commemoration is not celebrated. Instead, Labor Day is celebrated on the first Monday in September, commemorating a parade held on September 5, 1882 in New York and organized by the Noble Order of the Knights of Labor (Knights of Labor). US President Grover Cleveland sponsored the celebration in September for fear that the May date would reinforce the socialist movement in the United States since 1882. Canada joined in commemorating the first Monday in September instead of May 1 beginning in 1894.

History

Origin of the commemoration

The events that gave rise to this commemoration are contextualized at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the United States. At the end of the 19th century Chicago was the second largest city in the United States. Thousands of unemployed cattle ranchers arrived each year from the west and southeast by rail, creating the first humble villages that housed hundreds of thousands of workers. In addition, these urban centers welcomed emigrants from all over the world throughout the 19th century.

The demand for an 8-hour working day

One of the basic demands of the workers was the eight-hour day. One of the priority objectives was to enforce the maxim of: "eight hours of work, eight hours of leisure and eight hours of rest". In this context, several movements took place; in 1829 a movement was formed to petition the New York legislature for the eight-hour day. Previously, there was a law that prohibited working more than 18 hours, "except in cases of necessity." If there was no such need, any railroad official who forced an engine driver or stoker to work 18-hour days was required to pay a $25 fine.

Most of the workers were affiliated with the Noble Order of the Knights of Labor, but the American Federation of Labor, initially socialist (although some sources indicate its anarchist origins), had more preponderance. In its fourth congress, held on October 17, 1884, it had resolved that from May 1, 1886 the legal duration of the working day should be eight hours, going on strike if this demand was not obtained and recommending to all trade unions that try to make laws in this sense in their jurisdictions. This resolution aroused the interest of the organizations, which saw the possibility of obtaining a greater number of jobs with the eight-hour day.

In 1868, President Andrew Johnson enacted the so-called Ingersoll Act, establishing the eight-hour workday. Soon after, nineteen states enacted laws with maximum working days of eight and ten hours, although always with clauses that allowed them to be increased to between 14 and 18 hours. Still, due to the lack of compliance with the Ingersoll Act, labor and union organizations in the United States mobilized. The generalist press in the United States, reactionary and aligning itself with the business theses, described the movement as "outrageous and disrespectful", "delusion of unpatriotic lunatics", and stated that it was "the same as asking for a salary to be paid without fulfilling any working hour".

On May 1st, the strike

On Saturday, May 1, 1886, 200,000 workers went on strike while another 200,000 obtained this conquest with the simple threat of unemployment.

In Chicago, where the conditions of the workers were much worse than in other cities in the country, the mobilizations continued on May 2 and 3. The only factory that was working was the Helmans agricultural machinery factory that had been on strike since February 16 because they wanted to deduct an amount from the workers' salaries for the construction of a church. Production was maintained based on scabs. On the 2nd, the police had violently broken up a demonstration of more than 50,000 people and on the 3rd a rally was held in front of its doors; When the anarchist August Spies was in the rostrum, the siren sounded for a turn of strikebreakers. The concentrates were thrown on the scabs (yellow) starting a pitched fight. A company of policemen, without any warning, proceeded to shoot people at point-blank range, causing 6 deaths and several dozen wounded.

Journalist Adolph Fischer, editor of the Arbeiter Zeitung, rushed to his newspaper where he drafted a proclamation (later to be used as the main indictment in the trial that led to his hanging) printing 25,000 leaflets. The proclamation read:

Workers: The class war has begun. Yesterday, in front of the McCormik factory, the workers were shot. His blood demands revenge!Who can doubt that the jackals that govern us are avid of working blood? But workers are not a flock of rams. To white terror we respond with red terror! Death is preferable than misery.

If the workers are shot, we respond in such a way that the masters remember it for a long time.

It is the need that makes us scream: to arms!

Yesterday, the women and children of the poor cried to their husbands and their fathers shot, while in the palaces of the rich they filled expensive wine vessels and drank to the health of the bandits of order...

Dry your tears, those you suffer!

Get up!

The proclamation ended by calling an act of protest for the following day, the fourth, at four in the afternoon, in Haymarket Square. Permission was obtained from Mayor Harrison to hold an event at 7:30 p.m. in Haymarket Park. The events that took place there are known as the Haymarket riot.

The Haymarket Riot

More than 20,000 people gathered in Haymarket Square and were repressed by 180 uniformed police officers. An explosive device exploded among the police officers causing one death and several injuries. The police opened fire on the crowd, killing 38 people and injuring more than 200.

Chicago was declared in a state of siege and a curfew detained hundreds of workers who were beaten and tortured, accused of the murder of the police officer.

These repressive acts were supported by a press campaign with quotes such as:

What better suspects than the larger flat of anarchists. To the gallows the killer brutes, communist red ruffians, blood-thirsty monsters, bomb-makers, gentuza that are nothing other than the European regimen that sought our shores to abuse our hospitality and defy the authority of our nation, and that in all these years they have done nothing but to proclaim wary and dangerous doctrines!

La Prensa demanded a summary judgment by the Supreme Court, holding eight anarchists and all the prominent figures of the labor movement responsible.

On June 21, 1886, the case was initiated against 31 responsible parties, which were later reduced to eight. The irregularities in the trial were many, violating all procedural norms in its form and substance, so much so that it has come to be described as a farce trial. The courts were found guilty. Three of them were sentenced to prison and five to death, which would be executed by hanging. The details of the sentences are as follows:

- Prison

- Samuel Fielden, 39, Methodist Pastor and Textile Worker, sentenced to life imprisonment.

- Oscar Neebe, American, 36 years old, seller, sentenced to 15 years of forced labor.

- Michael Schwab German, 33, typographer, sentenced to life imprisonment.

- Death

- George Engel, German, 50, typographer.

- German Adolph Fischer, 30, journalist.

- Albert Parsons, an American, 39 years old, journalist, Mexican husband Lucy González Parsons, although it was proved that he was not present in the place, surrendered to be with his colleagues and was judged equally.

- August Vincent Theodore Spies, German, 31 years, journalist.

- Louis Lingg, German, 22, carpenter for not being executed committed suicide in his own cell.

The sentences were executed on November 11, 1887. José Martí, who at that time was working as a correspondent in Chicago for the Argentine newspaper La Nación narrated it like this;

... they leave their cells. They shake hands, smile. They read the sentence, hold their hands on their backs with wives, cling their arms to the body with a leather girdle and put a white mortaja like the robe of Christian catechins. Below is the concurrence, sitting in row of chairs in front of the slope as in a theater... Firmness in Fischer's face, prayer in Spies's, pride in Parsons's, Engel makes a joke about his hood, Spies screams: "The voice you are going to suffocate will be more powerful in the future than how many words I could say now." They lower their hoods, then a sign, a noise, the trap yields, the four bodies fall and sway into an amazing dance...

The events in Chicago also cost the lives of many workers and union leaders; There is no exact number, but thousands were fired, arrested, prosecuted, shot or tortured. Most were European immigrants: Italian, Spanish, German, Irish, Russian, Polish, and from other Slavic countries.

Achievement of the eight-hour working day

At the end of May 1886, various employer sectors agreed to grant the 8-hour day to several hundred thousand workers. The success was such that the Federation of Organized Trades and Unions expressed its jubilation in these words: "Never in the history of this country has there been such a general uprising among the industrial masses. The desire for a shortening of the working day has prompted millions of workers to join existing organizations, where up to now they have remained indifferent to union agitation.

The achievement of the 8-hour day marked a turning point in the world labor movement. Friedrich Engels himself in the preface to the 1890 German edition of The Communist Manifesto says:

For today, at the time of writing these lines, the proletariat of Europe and America revisits its forces, mobilized for the first time in a single army, under a single banner and for a single immediate objective: the legal fixation of the normal eight-hour day, already proclaimed in 1866 by the Congress of the International held in Geneva and again in 1889 by the Labour Congress of Paris. Today's show will show the capitalists and the landlords of all countries that, in fact, the proletarians of all countries are united. Oh, if Marx were by my side to see him with his own eyes!

Consolidation and extension during the 20th century

After the events in the United States, the Second International gave great impetus to attempts to convert May 1st into a holiday, always simultaneously demanding the reduction of the working day to eight hours. In 1904, the Second International meeting in Amsterdam asked "all the parties, unions and social democratic organizations to fight energetically on May Day to achieve the legal establishment of the 8-hour day and to fulfill the demands of the proletariat to achieve peace." universal". At the same time the congress made it "obligatory for the proletarian organizations of all countries to stop working on May 1, whenever possible and without prejudice to the workers". In this way, organizations throughout the world tried to make May Day an official holiday in honor of the working class, which was gradually achieved in most countries.

In Europe during the second decade of the century there were some milestones. On April 23, 1919, the French Senate ratified the eight-hour workday and made May 1, 1919, a non-working day for the first time. Two months earlier in Spain, the famous strike of La Canadiense, led by the anarchist movements in Barcelona, had managed to get the Decree on the eight-hour work day approved throughout the country, making Spain was the first country in Europe to promulgate this claim, although years later, between 1923 and 1930, Labor Day was celebrated without demonstrations, due to the deprivation of this right during the military dictatorship of General Primo de Rivera, although from 1931 to 1936, during the Republic, it was commemorated in the main Spanish cities.

After the Second World War and the adoption of socialism as a political system in many countries in Europe and Asia, and later in Africa and America, it gave new impetus to International Workers' Day, while in capitalist countries In Europe, the influence of the left-wing parties grew, and with them the celebrations on this day. Therefore, during the second half of the XX century, May Day became a day of great official celebrations, popular demonstrations and military parades in countries such as the Soviet Union - where the great parades in front of the Moscow Kremlin and Lenin's mausoleum became famous, the German Democratic Republic or China.

In 1954, Pope Pius XII declared May 1 the feast of Saint Joseph the Worker, in Saint Peter's Square in Rome, adding a Catholic message to this day, and opening a new concept of "Catholic workers& #34;, with social demands and faith, always in opposition to the methods and ideas of communist and socialist organizations, the main organizers of the celebration and generally hostile to religion.

In other capitalist countries, especially in the United States, both companies and the government discouraged the celebrations of May 1st, to avoid a greater influence of left-wing parties and unions in the country. In Portugal, for example, International Workers' Day began to be celebrated freely after the triumph of the Carnation Revolution on April 25, 1974, and in Spain it was not celebrated, with the original meaning of the commemoration, between 1939 and 1977, during the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, which was replaced by the celebration of the festival of San José Obrero after its Vatican proclamation.

Due to the climate of vindication on the one hand and the division of the world on the other during the second half of the XX century, The celebrations of International Workers' Day sometimes led to numerous confrontations, riots and massacres, which caused or were the reason for political changes with national and international relevance in some cases. For example, in Turkey the massacre of Taksim Square in Istanbul took place on May 1, 1977, with a balance of dozens of deaths; the massacre occurred in the midst of a climate of confrontation between left and right throughout the entire the 1970s that ended with the coup d'état of September 12, 1980.

In the 21st century

At the beginning of the XXI century, in many countries, the media began to name International Day of Workers, such as "Labor Day" in an attempt to separate the celebration, already deeply rooted, from its commemorative and protest origin.

In other countries, generally British-colonized countries, they have been celebrating the so-called Labor Day (literally "Labor Day") on dates other than May 1st. In the United States of America and Canada, Labor Day is the first Monday in September; in New Zealand, the fourth Monday in October; in Australia, each federal state decides the date of celebration: the first Monday of October in the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales and South Australia; the second Monday in March, in Victoria and Tasmania; the first Monday in March, in Western Australia; and on May 1 in Queensland and the Northern Territory. Due to the fact that the festivity has an official character in many countries, currently part of the population continues to participate in the celebrations and their claims, while another part takes the day off for leisure activities, etc.

.

Contenido relacionado

Galicia

Antanas Mockus

Origins of jazz