Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution or First Industrial Revolution is the process of economic, social and technological transformation that began in the second half of the XVIII in the Kingdom of Great Britain, which spread a few decades later to much of Western Europe and Anglo-Saxon America, ending between 1820 and 1840. During This period saw the greatest set of economic, technological and social transformations in the history of humanity since the Neolithic, which saw the transition from a rural economy based fundamentally on agriculture and commerce to an economy of an urban, industrialized and mechanized.

The Industrial Revolution marks a turning point in history, modifying and influencing all aspects of daily life in one way or another. Both agricultural production and the nascent industry multiplied while production time decreased. Starting in 1800, wealth and per capita income multiplied as never before in history, since until then GDP per capita had remained practically stagnant for centuries. In the words of Nobel laureate Robert Lucas:

Date: ... for the first time in history, the living standards of the masses of ordinary people have begun to undergo sustained growth (...) Nothing remotely like this economic behaviour is mentioned by the classical economists, even as a theoretical possibility...Date translation: ... for the first time in history, the standard of living of the masses and the common people experienced sustained growth (...) Nothing remotely like this economic behavior is pointed out by classic economists, not even as a theoretical possibility...

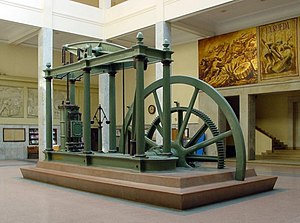

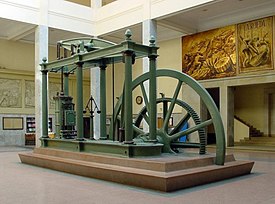

From this moment on, a transition began that would put an end to centuries of a workforce based on manual labor and the use of animal traction, these being replaced by machinery for industrial manufacturing and for the transport of goods and services. passengers. This transition began towards the end of the 18th century in the textile industry, as well as in relation to the extraction and use of coal. The expansion of trade was possible thanks to the development of communications, with the construction of railways, canals, and highways. The transition from a fundamentally agricultural economy to an industrial economy greatly influenced the population, which experienced rapid growth, especially in urban areas. The introduction of James Watt's steam engine (patented in 1769) in different industries was the definitive step in the success of this revolution, since its use meant a spectacular increase in production capacity. Later, the development of ships and steam railways, as well as the development in the second half of the XIX of the internal combustion engine and electric power, represented unprecedented technological progress.

As a consequence of industrial development, new groups or social classes were born led by the proletariat —industrial workers and poor peasants— and the bourgeoisie, owner of the means of production and holder of most of the income and capital. This new social division gave rise to the development of social and labor problems, popular protests and new ideologies that advocated and demanded an improvement in the living conditions of the most disadvantaged classes, through unionism, socialism, anarchism, or the communism.

There is still discussion among historians and economists about the dates of the great changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution. The most accepted beginning of what we could call the First Industrial Revolution could be placed at the end of the XVIII century, while its conclusion was could situate it in the middle of the XIX century, with a transition period located between 1840 and 1870. For its part, what we could call the Second Industrial Revolution, would start from the middle of the XIX century to the beginning of the XX, highlighting 1914 as the most accepted date of completion, the year the First World War began. The Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, considered a key thinker in the history of the XX century, argued that the The start of the industrial revolution was to be placed in the 1780s, but its effects would not be clearly felt until 1830 or 1840. In contrast, the English economic historian T.S. Ashton declared for his part that the industrial revolution had its beginnings between 1760 and 1830.

The term "industrial revolution" is also a matter of discussion. Some historians of the 20th century, such as John Clapham and Nicholas Crafts, argue that the process of economic and social change was very gradual, so the term "revolution" would be inappropriate. Likewise, the nickname "industrial" is questioned, since the process also included agrarian, social, energy, and demographic changes. These issues continue to be the subject of debate among historians and economists.

Background and causes

The beginnings of European industrialization must be found in the Modern Age. From the XVI century, advances in commerce, financial methods, banking and a certain technical progress in navigation can be glimpsed, printing or watchmaking. However, these advances were always hampered by epidemics, constant and long wars, and famines that did not allow the spread of new knowledge or large population growth. According to historian Angus Maddison, Western Europe experienced virtually zero population growth between 1500 and 1800.

The Renaissance marked another turning point with the appearance of the first capitalist societies in the Netherlands and northern Italy. It is from the middle of the XVIII century when Europe began to distance itself from the rest of the world and lay the foundations of the future industrial society due to the development, still primitive, of heavy industry and mining. The alliance of merchants with farmers increased productivity, which in turn caused a population explosion, accentuated from of the XIX. The Industrial Revolution was characterized by the transition from an agricultural and manual economy to a commercial and industrial one whose ideology was based on rationalism, reason and scientific innovation.

Another of the main triggers for the Revolution was born of necessity. Although an industrial base already existed in some places in Europe, such as Great Britain, the Napoleonic Wars consolidated European industry. Due to the war, which was spreading through most of Europe, imports of many products and raw materials were suspended. This forced governments to pressure their industries and the nation in general to produce more and better than before, developing industries that did not exist before. Industrialization took place in different waves in different countries. The first industrial areas appeared in Britain at the end of the 18th century century, spreading to Belgium and France at the beginning of the XIX and Germany and the United States in the middle of the century, Japan from 1868 and Russia, Italy and Spain at the end of the century. Among the reasons were some as diverse as the notable absence of major wars between 1815 and 1914, the acceptance of the market economy and the consequent birth of capitalism, the break with the past, a certain monetary balance and the absence of inflation.

Other interpretations

Other interpretations suggest that this new change in mentality and the subsequent evolution of the economic system was due to moral and religious causes. The Protestant Reformation of Martin Luther and John Calvin brought with it a change of mentality in the treatment and vision regarding work. According to Max Weber, Protestantism considers work and effort as a good and a fundamental value, unlike Catholic ethics, which considers it a punishment for original sin. This would partly explain the differences in the development of the different European nations, having as pioneers Protestant countries such as Great Britain, Germany or the Netherlands and Spain, Portugal and Italy as backward countries, all of them Catholic. This interpretation is still highly disputed.

Great Britain

The Industrial Revolution originated in England due to various factors, the elucidation of which is one of the most transcendental historiographical issues.

As for technical factors, it was one of the countries with the greatest availability of essential raw materials, especially coal, essential to power the steam engine that was the great engine of the early Industrial Revolution, as well as to use coke in the blast furnaces of the iron and steel industry, the main sector since the mid-XIX century. Its advantage over wood, the traditional fuel, is not so much its calorific value as the mere possibility of continuity of supply (wood, despite being a renewable source, is limited by deforestation; while coal, a fossil fuel and therefore non-renewable, it is only renewable due to the depletion of the reserves, the extension of which increases with the price and the technical possibilities of extraction). Casting with coke allows a greater supply of iron, quality improvements and cost reduction of this material.

As ideological, political and social factors, English society had a tendency towards less absolutism and more inclusive institutions. Beginning with the Magna Carta of 1215, which limited the power of the king, it had gone through the so-called crisis of the 17th century in a particular way: while southern and eastern Europe refeudalized and established absolute monarchies, the English Civil War (1642 -1651) and the subsequent glorious revolution (1688) determined the establishment of a parliamentary monarchy based on the division of powers, individual freedom and a level of legal security (with the Common Law) that it provided sufficient guarantees for the private entrepreneur; Many of them emerged from active minorities of religious dissidents that in other nations would not have consented (authors such as Max Weber explicitly link The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism). An important symptom was the spectacular development of the industrial patent system.

Some authors also mention enclosures as a factor that contributed to industrialization, as an incipient "privatization" of resources. Also, increasing liberalization, and the reduction of restrictions imposed by unions on the installation of industries and technological change.

As a geostrategic factor, during the 18th century England (which after the signing of the Act of Union with Scotland in 1707 and of the Act of Union with Ireland in 1800, after the defeat of the Irish rebellion of 1798, they achieved the union with Scotland and Ireland, forming the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland) built a naval fleet that converted it (since the treaty of Utrecht, 1714, and indisputably since the battle of Trafalgar, 1805) in a true thalassocracy that owned the seas and a vast colonial empire. Despite the loss of the Thirteen Colonies, emancipated in the War of Independence of the United States (1776-1781), it controlled, among others, the territories of the Indian subcontinent, an important source of raw materials for its industry, notably the cotton that fed the textile industry, as well as a captive market for the products of the metropolis. The patriotic song Rule Britannia (1740) explicitly stated: rule the waves.

Demographic revolution

During the industrial revolution there was a spectacular increase in the population, mainly due to the drop in the mortality rate caused by the improvement of hygienic, sanitary and nutritional conditions that was reflected to a large extent in the reduction of mortality childish. In this period the first vaccinations were born and the sewerage and wastewater treatment systems were improved. A more abundant and regular diet, not subject to crop fluctuations, lowered the incidence of epidemics and made possible the near disappearance of catastrophic mortality, especially infant mortality.

The population of England and Wales, which had remained constant at around 6 million from 1700 to 1740, increased sharply from this date and reached 8.3 million in 1801, doubling in fifty years to reach 16.8 million in 1850 and by 1901 it had nearly doubled again to 30.5 million. In Europe, the population rose from 100 million in 1700 to 400 million in 1900. The Industrial Revolution was thus the first historical period during in which there was simultaneously an increase in population and an increase in per capita income. The increase in population was a stimulus for industrial growth, since it provided both abundant labor for new industries and otherwise led to an increase in domestic demand for new products.

The increase in the urban population in cities with a medieval layout led to overcrowding, unhealthy conditions and the appearance of the first social pathologies (alcoholism, prostitution and delinquency).

The birth of the factory system: the textile industry

Between the late 17th century and early 18th century, the British government passed a series of laws to protect the British woolen industry from the increasing amount of cotton cloth being imported from East India.

There also began to be a greater demand for thick fabrics, which were manufactured by the British industry in the town of Lancashire, where the production of corduroy stood out, made from intertwined fibers of linen and cotton. Linen was used to provide more resistance to the fabric, whose main material, cotton, did not have sufficient resistance, although this resulting mixture was not as soft as 100% cotton fabrics and was more difficult to sew.

Until the birth of the textile industry, weaving and spinning in general was done at home, in most cases for own consumption. This productive method, based on the fact that production was dispersed and took place in the workers' homes, is often referred to in English as the Putting-out system (Putting-out system) as opposed to the later system industrial or factory system. Only on specific occasions were the works carried out in the workshop of a master weaver. Under the putting-out system, the workers, before manufacturing their product, entered into contracts with merchants and vendors, who often supplied them with the necessary raw materials. In the off-season, the farmers' wives usually made the yarn while the men produced the cloth. Using the spinning wheel, at any time between four and eight spinners could lend a hand to the weaver.

One of the great inventions of the textile industry was the flying shuttle, patented in 1733 by John Kay, which allowed some automation of the weaving process. Subsequent improvements, notably those of 1747, made it possible to double the production capacity of the weavers, which also aggravated the imbalance that existed between spinning and weaving. This invention came into wide use throughout Lancashire in the 1760s, when Robert Kay, son of John Kay, invented the drop box.

Lewis Paul patented in Birmingham, with the help of John Wyatt, the roller spinning machine and the flyer-and-bobbin system, which achieved a more uniform thickness in the process of making the money. Paul and Wyatt opened a factory in Birmingham using a new donkey-powered rolling machine. In 1743 a factory was opened in Northampton employing five machines like Paul's with fifty spindles each. It was in operation until 1764. A similar factory was built by Daniel Bourn in Leominster, but a fire destroyed it. Both Paul and Bourn had patented the wool carder in 1748. The use of two sets of rollers rotating at different speeds was later used in the first cotton spinning mill. Lewis's invention was further improved upon by Richard Arkwright with his Water frame (1769) and by Samuel Crompton with his Spinning mule (1779).

| Year | 1803 | 1820 | 1829 | 1833 | 1857 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tears | 2400 | 14 650 | 55 500 | 100 000 | 250 000 |

In 1764 in the Lancashire village of Stanhill, James Hargreaves invented the Jenny spinning machine, which he patented in 1770. It was the first machine to use several spindles efficiently. Spinner Jenny worked in a similar way to the spinning wheel. It was a simple machine, built of wood, and costing only about £6 (a 40-spindle model) in 1792. It was mainly used in households or by small craftsmen. The Jenny Spinner produced a slightly twisted thread only suitable for weaving, which twisted.

The Water frame, invented by Richard Arkwright, was patented by him and two partners in 1769. The design was based in part on a spinning machine built by Thomas High, who was hired by Arkwright.

In 1786, Edmund Cartwright invented the first power loom. In 1793, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, allowing Britain to import large quantities of cotton for its textile industry at low cost from the South from the United States.

International trade

Industrial Economics

However, and despite all the above factors, the Industrial Revolution could not have prospered without the competition and development of transport, which will take the goods produced in the factory to the markets where they are consumed.

These new forms of transport are necessary not only in internal trade, but also in international trade, since the great national and international markets are created at this time. International trade is liberalized, especially after the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) that liberalizes the commercial relations of England, and other European countries, with Spanish America. An end to privileged companies and economic protectionism; and an imperialist policy and the elimination of trade union privileges are advocated. In addition, ecclesiastical, stately and communal lands are confiscated, to put new lands on the market and create a new concept of property. The Industrial Revolution also generated a widening of foreign markets and a new international division of labor (IDL). New markets were conquered by lowering the cost of machine-made products, by new transportation systems and the opening of communication routes, as well as by an expansionist policy.

The United Kingdom was the first to carry out a whole series of transformations that placed it at the head of all the countries in the world. Changes in agriculture, population, transportation, technology and industries, favored industrial development. The cotton textile industry was the leading sector of industrialization and the base of capital accumulation that will open the way, in a second phase, to the iron and steel industry and the railroad.

By the middle of the 18th century, British industry had solid foundations and double expansion: the goods industries production and consumer goods. The growth of coal mining and the steel industry was even stimulated with the construction of the railway. Thus, in Great Britain industrial capitalism fully developed, which explains its industrial supremacy until about 1870, as well as financial and commercial supremacy from the middle of the century XVIII until the First World War (1914). In the rest of Europe and in other regions such as North America or Japan, industrialization was much later and followed different patterns from the British.

A few countries industrialized between 1850 and 1914: France, Germany, and Belgium. In 1850 there was hardly a modern factory in continental Europe, only in Belgium is there a process of revolution followed by that of the United Kingdom. In the second half of the XIX century, the industrialization of Germany strengthened in Thuringia and Saxony.

Other countries followed a different and very late industrialization model: Italy, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Spain or Russia. Their industrialization began timidly in the last decades of the XIX century, ending long after 1914.

Transportation

The Railroad

The railway, born in the 18th century, is one of the great protagonists of the Industrial Revolution. In its beginnings, animal power was used as a means of locomotion, the rails were made of wood and their use was limited to mines for transporting coal. In a book published in 1797, Carz claimed to have been the first to think of replacing wood for iron. The first concession of the Parliament of England for the construction of a railway - moved by horses - dates back to 1801; it was a line between Wandsworth and Croydon about 13 kilometers long and at a cost of 60,000 pounds. The great railway revolution began in 1814, when George Stephenson used the steam engine as a means of locomotion. His invention was a success and began to be used immediately in the mines, being able to transport eight wagons of 30 tons at a speed of 7 km / h. These results were enough to expand the use of the machine to other services. It was 1821 when Parliament authorized the construction of the first steam-powered railway line between Stockton and Darlington. The line was inaugurated in 1825 with a machine operated by Stephenson himself pulling 34 wagons at a speed of between 10 and 12 miles per hour —16–19 km/h—; The newspaper The Times he described this feat as follows:

Three steam machines with fifty horsepower each have served to drag thirteen cars, loaded with goods and various products on the height of the tilted plane forming the road. There the cars have been hooked to a machine called "The Experience" in addition to a number of cars that brought shareholders, authorities and guests (...) It is set in motion and men on horseback attempt to follow the cars, but soon distanced, where the slope was stronger the convoy reached 25 miles/h. (40km/h).

In the following 5 years, Parliament authorized the construction of 23 new railway lines, among which was the famous line between Manchester and Liverpool, its builders being the first to offer passenger transport services on the railway. At that time, the security that the locomotives could offer was distrusted, but the reception was very good, improving the benefits derived from this service by 10%, although the income from the transport of cotton, fabrics, coal and cattle was still low. majority. This success was also addressed by George Porter, who in his book The Nation's Progress says:

Since then [refers to the construction of the cited line] It has been observed that when a railway line was built between two cities, the number of travelers on the route between one and the other is quadrupled.

On this occasion, it was Stephenson himself who won the bid on this line, becoming his Rocket in charge of towing a 12-ton train at 22 km/h. The first rail mail it was sent on 11 November 1830. Arrival times were greatly reduced, with mail between London and Manchester arriving in approximately 18 hours. In England, following the slogan laissez faire, the State did not intervene in the construction or subsidy of the railway but limited itself to granting licenses and construction and exploitation permits; in this way enormous fortunes were spent with the objective of obtaining the different permits; for example the Great Western cost £89,000 in preliminary expenses and others such as the London and Birmingham £62,000.

The railways were initially narrow gauge and only allowed speeds between 15 and 20 kilometers per hour, but in 1840 the tracks had been widened and speeds of almost 40 km/h could be achieved.

The first continental country to follow the English example was Belgium with two lines Brussels-Malines and Malines-Antwerp in 1835. The first year they carried 70,000 passengers. The cost was very low, and the Brussels-Antwerp ticket cost only one franc. from iron deficiency. The French government, seeing the potential of the device, ordered a study for a national plan for the railways. The study was completed in 1837 and impatient capitalists pressured the government to carry out the project in order to speculate with the works and land. The plan consisted of seven lines with a center in Paris, which would link the Atlantic, the Mediterranean and the Rhine. Unlike in England and Belgium, the state took charge, at least in part, of their construction and operation, contributing 150,000 francs per kilometer of track and building the necessary infrastructure. Meanwhile, private companies contributed 100,000 francs for buildings and material. After 40 years of private administration and exploitation, the system would pass to the State. Romantic and conservative socialists opposed the project, the former demanding that the system be out of state from day one and the latter considering it too expensive. Finally the plan was approved, but some agreements were revised and in practice the construction and operation it was almost exclusively paid by the private sector. In 1857 the network was consolidated, being owned by 6 large companies. Due to the obligation to transfer the property to the State after 40 years of exploitation, its care and maintenance was greatly neglected, for which the French government was forced to extend the term by 99 more years, even committing to pay the obligations to its expiration.

In Germany the first line was built in 1835 with an extension of seven kilometers between Nuremberg and Fürth, but it was in 1839 when the first important line was built between Dresden and Leipzig, promoted by the professor of political economy List, one of the main promoters of the Nuremberg-Fürth line. The railroad was soon seen as a powerful political weapon; At the time of the railway's appearance, Germany was divided into more than 300 small states and autonomous cities. Since the construction of the Dresden-Leipzig line, all German cities wanted to unite with their neighbors, which, in addition to a great economic boost, did a great service for the triumph of the Zollverein. Contrary to the rest Of countries, in Germany the administration was in charge of monitoring or managing all the railways. In 1850 the Zollverein already had 5,800 kilometers, almost double that of all of France. Hannover, Bremen, Hamburg, Berlin, Frankfurt formed a great line that passed over the main industrial centers and linked Germany with Switzerland through Basel and Austria through Moravia and Silesia.

Starting in the 1820s, railroads and steamships made their way to the United States and soon conquered public opinion. Stevens conducted a first test run in Hoboken, which caused great interest among Pennsylvania businessmen, who bought a locomotive from England. As in Great Britain, the accumulation of capital made it possible only a year after the start of construction. of a first line between Washington and Winchester. In 1830 a locomotive called Best Friend exploded while traveling on the Charleston-Hambourg line because the engineer had sat on the exhaust valve due to the discomfort he felt due to the hissing of the steam leaving. But far from backing down, the country progressed at a frenetic pace and by the mid-1830s it was already producing its own locomotives at the West Point foundry, ensuring a strong national industry. Since then the United States laid rails across its vast territory at a speed far greater than Europe. If in 1830 it had only 65 kilometers of track —against 316 Europeans, 276 of them in Great Britain—, 10 years later it already surpassed Europe with 4,509 kilometers against 3,543 Europeans. In 1850 the railways already totaled 14,400 kilometers. One of the problems posed by the railways was the track gauge, which varied in width in different countries, forcing numerous transfers to the delight of hoteliers. But problems aside, the travel time only decreased; thus, in just a few years it took no more than 20 hours to travel from Boston to New York by rail when before it took about 80.

In Italy, d'Azeglio's predictions that the railways would sew up the boot did not go beyond simple promises, since until 1845 there were only small isolated lines such as the Milan-Monza, Padua-Venice line, Liorna-Pisa or the Campania line that Ferdinand of Naples built for his recreation and private use. In Hungary there was only a small track around Budapest and in Russia the tsarism had to impose the construction of the Moscow-Saint Petersburg line due to to the numerous detractors. In Spain, the great pull and enthusiasm that the invention had produced very early faded in the civil war of 1833, which paralyzed all construction works due to the distrust of the capitalists. We had to wait until 1843 when Juan Manuel Roca and Miguel Biada were awarded the construction and operation of the Barcelona-Mataró railway, which was built in just five years under the direction of the English engineer Locke, its inauguration was on October 28, 1848, a journey of 28 km and 600 m that was completed in 35 minutes. In 1851 the second Spanish railway that covered the Madrid-Aranjuez line made its first trip, whose concession had been granted in 1844 with an extension to Cádiz. In 1850 the construction of the first Spanish locomotive began, completed in 1852.

Exceptions aside, in the period between 1820 and 1840, Great Britain maintained a clear advantage over the rest of the world. It was the only one that had a good transport network between its main cities. He worked with a real frenzy between 1840 and 1847 despite the latent rivalry between the opposition, financial groups, Turnpike trusts and the population, whose livelihood continued to be the roads. A similar situation occurred in Belgium, which in 1843 had even more kilometers than France and a very favorable public opinion to the railway. There were not a few who saw a great danger, even fatal, in the railway. Since the 18th century, when they were launched in England, there were voices, even from the British Royal Academy of Sciences, that they suggested that at speeds above 40 km/h passengers would suffocate, go blind and cattle would go mad. It was also feared the destruction of farmland or that people and goods would be thrown from the device by its "diabladas" speeds.

After the first half of the century, the following half century between 1851 and 1901, known as the Railway Age, saw the heyday and definitive reign of the railway. But mechanical traction on rails is above all the work of the West. In 1860, Europe and the United States shared more or less 198,000 kilometers equally while the rest of the world had no more than 15,000 kilometers, most of them located in European colonies. In 1910, more than a million had already been built. of kilometers of which 380,000 are in the US and 330,000 in Europe. Its construction required an enormous effort, mobilizing large amounts of capital, workers and stimulating the metallurgical industry and the construction of gigantic workshops, in addition to give its maximum splendor to the steam engine. In addition to the wagons and locomotives, the rails on which they circulated also evolved. The steel rail replaced the iron rail and the wood of the sleepers began to be injected with zinc chloride to prevent it from rotting. The railway also required a large infrastructure that it was necessary to develop, such as tunnels, which were excavated at the expense of worker suffering at very high temperatures with the use of compressed air drills and the lining of the galleries with cast iron, instead of wood; Ventilation was achieved with blowers. Some successes must be highlighted, among which are the tunnel that crosses Mont Cenis, built over 15 years and with an extension of 13,600 m at an altitude of 1,300 meters. Others such as the San Gotthard tunnel, over 15,000 meters they were finished in less than 10 years using the automatic drilling machine, the working conditions being disastrous: the workers came to work at a temperature of 86 degrees. Outside Europe, the Americans built a tunnel under the Hudson River. Scandinavia is joined to Germany by the ferry-boats between Rügen and Malmö. While in the first half of the century the locomotive had barely gained speed without ever exceeding 40 km/h, it makes decisive progress on the English engineer Crampton's idea of placing the driving wheels behind the boiler (and not below)., wheels that are coupled, transferring the rotational movement. In 1850 the average speed, which stood at 27 km/h, rose in 1880 to 74 km/h in England and 59 km/h in the United States. In 1890 the Empire-State-Express exceeded for the first time in history the 100 km/h between New York and Buffalo. Crossing France from one end by rail only took 14 hours. In this second part of the century the cost of the ticket decreased between 50 and 70%.

The performance of the locomotive increased steadily. The handbrake was replaced by a new compressed-air hydraulic brake. Passenger carriages were fitted with shale-oil gas lighting or electric lighting at the turn of the century, the London-Brighton line being the first to incorporate it.. The steam engine, the heart of the machine, also provides heating in the wagons. The so-called Boggie or multi-axle frame allowed the convoy to make much sharper curves, reducing risks, as it adapted to the curvature of the track. The so-called palace-cars on the longest lines for rich families in which they enjoyed all kinds of comforts and without having to mix with the rest of the passengers. a daily newspaper with the news received by telegraph at the stations.

Excepting Great Britain, Belgium, and parts of Spain and Germany, railways did not draw networks anywhere before 1860. In France a serious effort was finally made after the Second Empire and at the dawn of the Third Republic. In this second half of the century, the backbone of European railways was beginning to be glimpsed. Its limits extended from northern France to Upper Silesia from east to west and from Germany to northern Italy from north to south; in the center, Switzerland distributes the traffic across the continent. On the other hand, most of Italy, the Iberian Peninsula and the eastern countries were left out. In the United States, great achievements continue to be made. In 1869 the first transcontinental connecting the country from east to west was completed. The construction was directed by the ruthless General Grenville M. Dodge as if it were a military campaign. He used demobilized soldiers, Irish immigrants and even Chinese in California as manpower, but this triumph did not come easily; Indians, the irregular relief and, above all, the competition between the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific made the situation extremely difficult. But enthusiasm prevails and in 1893 there were already 5 other transcontinental lines in operation, being used as a means of colonization in the American West or in British Columbia as a means of pressure to obtain its adhesion to the Union.

Although late, the Russian effort is presented, achieved thanks to loans from the West. First, the Transcaspian was built, which from 1905 was complemented by the Transaralian. In Siberia the difficulties were great: ice, water infiltration, huge rivers, low human density, enormous distances, not to mention the irregular relief. But the old routes and roads were no longer sufficient and the longest railway in the world was started in 1891 and reached its destination, Vladivostok, thanks to an agreement with China, in 1902.

Thus, the railroad not only served to revolutionize the world of transportation, both material and human, but was used as an excellent instrument of union. It served well in the reconciliation and annexation of new territories to the United States and the Empire German knew how much he owed the railway to leave it in private hands. In Italy it facilitated the hegemony of the House of Savoy. The same was not the case in France or Great Britain, where they were mostly in private hands, although in England they provided unparalleled service, elevating the nascent British Empire to world hegemony. By 1850 the railway had carried between 400 and 500 million travelers and between 200 and 300 million tons of merchandise since its birth. Five decades later, in 1905 alone it carried between 4 and 5 billion travelers.

The Steamboat

Before the 19th century the long European naval tradition had relied on the control of the winds as a means of propulsion and safety rather than speed at sea. At the beginning of the century, it took no less than two or three weeks to cross the Atlantic from east to west, while it took between 30 and 40 days from west to east. With the formation of the European colonial empires, it became necessary to develop a technology that would ensure travel over water; in the 18th century the use of the sextant, maps with the notations of the winds and the chronometer became widespread. The invention of the new boat started from the works of Jouffroy d'Abbens on the Seine and those of Fulton with his Clermont machine. It was in the United States where the first tests of the wheeled ship took place on the Hudson River. In 1815 there were already a hundred of these wheeled ships that obtained their energy from firewood, a cheap and abundant material. The Savannah managed to cross the North Atlantic in 29 days in 1819 and the Sphink, which brought the news of the capture of Algiers to France, developed a speed of 6 knots. But the problems were numerous: the paddles used caused a great waste of energy, there was a risk of fire or explosion on board, their speed was even less than that developed by sailing ships and the military power still opposed their use as a transport ship. war.

But despite the difficulties the advances continued and in 1838, using a combination of steam and sail, the ships Sirius and Great Western crossed the Atlantic between Liverpool and New York in 16 and 13 days respectively. The great advances came between 1840 and 1860 with the invention of the propeller, the first models being based on the Archimedean screw, the surface condenser and the Compound machine, which managed to save large amounts of fuel and the introduction of cylindrical boilers that made possible the production of high pressure steam.

What is certain is the supremacy of the sailboat over the steam during most of the century; the security and prestige it still enjoyed, especially in the United States, where most of the steamboat advances were also taking place, was indisputable. In 1850 the steamship had already carried 750,000 tons, although steam was still a long way from winning the game.

Roads and canals

The effort to build and improve roads (or roads) began in many parts of Europe before the Industrial Revolution. Since the end of the Napoleonic wars at the beginning of the 18th century and in the absence of other more effective means of communication, roads were extensively improved. At the beginning of the XIX century, the most advanced country in this matter was France, with a network of 33,000 kilometers of high quality that extended to Germany, Switzerland and Italy. The Netherlands, the Kingdom of Prussia or Switzerland had also experienced a great improvement in communications. At the other extreme were places like Sicily, whose construction did not begin until well into the 19th century, Tsarist Russia, which would not have its first road between Moscow and Saint Petersburg —its main cities— until 1834, or Spain, which counts before half of the XIX century with only 6000 kilometers of tracks, being also narrow and full of irregularities and deficiencies. In Great Britain, the rapid development of railways and canals makes their construction less important, but even so, the extensions and modernizations of the battered British network continue, counting in 1850 with more than 50,000 kilometers of route, 18,000 more than twenty years ago.

The technique in the construction of these communication routes also improves. In each country they are built differently, but the classic problems derived from these constructions, such as water leaks, maintenance or infrastructure, were solved in the 1820s and 1830s based on the improvements introduced by Mac Adam. or Telford. The use of stagecoach and public transport services develop and become widespread with speeds ranging between 10 and 15 km/h, being used for the transport of passengers, merchandise and mail. It is not until the beginning of the XX century when, thanks to the internal combustion engine and the development of the automobile, these layouts were given massive use.

The first canals began to be built in Great Britain in the 18th century with the in order to communicate the industrial centers of the British north with the seaports of the south and London. Canals were the first technology to allow easy and relatively fast transportation of goods across the country, several dozen times more tonnage being able to be transported per trip than by land transport. To this was added the relief of the country, completely flat, which allowed the canals to be built quickly and at a low price. By the early 1820s, there was already an established national network. The English example was copied in France, which, with a similar relief to the British, was able to develop its own system, which by the middle of the XIX century It had 8,500 kilometers of tracks. In Germany, thanks to its great rivers such as the Rhine and the Elbe, navigation was greatly favored, as well as trade, which experienced great development. In other countries like Spain, the construction of canals did not go beyond a project due to the difficult relief and the lack of capital. Outside the continent, the Americans with their entrepreneurial drive and their numerous lakes and large rivers managed to rapidly develop their own system, which, like the railroad, helped in the colonization and exploitation of the vast lands of the country. By early 1835 the US already had 7,000 kilometers of canals paving the way for the introduction of the steamboat to the country even faster than the ever-innovative Great Britain.

The use of canals in Great Britain began to decline from 1840, when the railway became the norm in the transport of goods and passengers. The irregular and later large-scale development of the railway in the rest of the countries, with the always notable exception of the United States, it sometimes extended full use of the canals until the dawn of the 20th century. Today the British channel network and the infrastructure linked to it is one of the most enduring and notable features of the Industrial Revolution in the country.

Consequences

The existence of more intense border controls prevented the spread of diseases and decreased the spread of epidemics like those that occurred in previous times. The British agricultural revolution also made food production more efficient with a lower contribution of the labor factor, encouraging the population that could not find agricultural jobs to look for jobs related to the industry and, therefore, originating a migratory movement from the countryside to cities as well as new development in factories. The colonial expansion of the 17th century accompanied by the development of international trade, the creation of financial markets and the accumulation of capital are considered factors influential, as was the scientific revolution of the 17th century. It can be said that it was produced in England because of its economic development.

The presence of a larger domestic market should also be seen as a catalyst for the Industrial Revolution, explaining in particular why it occurred in the UK.

The invention of the steam engine was one of the most important innovations of the Industrial Revolution. It made possible improvements in metalworking based on the use of coke instead of charcoal. In the 18th century the textile industry harnessed the power of water to run some machines. These industries became the model for organizing human labor in factories.

In addition to the innovation of machinery, the assembly line (Fordism) contributed a lot to the efficiency of factories.

- Agricultural revolution: progressive increase in production thanks to the investment of owners in new techniques and cultivation systems, in addition to the improvement of the use of fertilizers.

- The development of the commercial capital: The machines applied to the transports and the communication initiating a huge transformation. Now the relations between employers and workers are only labor and in order to obtain benefits.

- Demographic-social changes: the modernization of agriculture allowed population growth due to improved food. There were also advances in medicine and hygiene, hence the population grew. There was also a migration from the countryside to the city because the occupation in agricultural work decreased while the demand for work in cities grew.

Stages of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was divided into two stages: the first from 1750 to 1840, and the second from 1880 to 1914. All these changes brought consequences such as:

- Demographics: Transfer from the countryside to the city (rural exodus) — International Migration — Sustained Population Growth — Great Differences among Peoples — Economic Independence

- Economics: Serial production — Development of Capitalism — Apparition of Large Businesses — Uneven Exchanges

- Social: The Proletariat is Born—The Social question

- Environmental: Deterior of the environment and degradation of the landscape — Irrational exploitation of land and raw materials.

In the middle of the XIX century, England underwent a series of transformations known today as the Industrial Revolution within the which the most relevant were:

- The application of science and technology allowed the invention of machines that improved production processes.

- The depersonalization of working relationships: it is passed from the family workshop to the factory.

- The use of new energy sources, mainly coal.

- The revolution in transport: railways and steamship.

- The emergence of the urban proletariat.

The industrialization that originated in England and then spread throughout Europe not only had a great economic impact, but also generated enormous social transformations.

Urban proletariat. As a consequence of the agricultural and demographic revolution, there was a massive exodus of peasants to the cities; the former farmer became an industrial worker. The industrial city increased its population as a consequence of the natural growth of its inhabitants and the arrival of this new human contingent. The lack of rooms was the first problem suffered by this socially marginalized population; he had to live in confined spaces without minimal comforts and lacking hygiene. To this were added working days, which reached more than fourteen hours a day, in which men, women and children participated with miserable wages, and lacking legal protection against the arbitrariness of the owners of the factories or production centers. This set of ills that affected the urban proletariat was called the Social Question, alluding to the material and spiritual insufficiencies that affected them.

Industrial bourgeoisie. In contrast to the industrial proletariat, the economic and social power of the big businessmen was strengthened, thus consolidating the capitalist economic system, characterized by private ownership of the means of production and the regulation of prices by the market, in accordance with supply and demand.

In this scenario, the bourgeoisie definitively displaced the landed aristocracy and their situation of social privilege was based fundamentally on fortune and not on origin or blood. Endorsed by a doctrine that defended economic freedom, businessmen obtained great wealth, not only by selling and competing, but also by paying low wages for the workforce provided by the workers.

Proposals to solve the social problem. Faced with the situation of poverty and precariousness of the workers, criticisms and formulas arose to try to find a solution; for example, the utopian socialists, who aspired to create an ideal society, just and free from all kinds of social problems (for some, communism). Another proposal was the scientific socialism of Karl Marx, who proposed the proletarian revolution and the abolition of private property (Marxism); The Catholic Church, through Pope Leo XIII, also released the Encyclical Rerum Novarum (1891), the first social encyclical in history, which condemned abuses and demanded from states the obligation to protect the weakest Here is an excerpt from that encyclical:

(...) If the worker lends to others his forces to his industry, he lends them in order to achieve what is necessary to live and sustain himself and for all this with the work he puts on his part, he acquires the true and perfect right, not only to demand a salary, but to make this the use he wants (...)

These elements were decisive for the emergence of movements demanding workers' rights. During the XX century, in the midst of democratization processes, the labor movement managed to recognize the rights of workers and their integration into social participation. Other examples of tendencies that sought solutions were nationalisms, as well as fascisms in which workers and workers were considered a fundamental part of the productive development of the nation, for which reason they had to be protected by the State.

Industry Fundamentals

One of the fundamental principles of modern industry is that it never considers production processes as final or finished. Its technical-scientific base is revolutionary, thus generating the problem of technological obsolescence in ever shorter periods. From this perspective, it can be affirmed that all forms of production prior to modern industry (crafts and manufacturing) were essentially conservative, as knowledge was transmitted from generation to generation with hardly any changes. However, this characteristic of obsolescence and innovation is not limited to science and technology, but must be extended to the entire economic structure of modern societies. In this context, innovation is, by definition, negation, destruction, change, transformation is the permanent essence of modernity.

The development of new technologies, such as applied sciences, in a receptive social climate, is the time and place for an industrial revolution of chain innovations, as a cumulative process of technology, creating goods and services, improving the level of and the quality of life. An incipient capitalism, an educational system and an entrepreneurial spirit are basic. The lack of adequacy or correspondence between one and the other creates imbalances or injustices. It seems that this imbalance in industrialization processes, always socially very unstable, is in practice inevitable, but measurable in order to build improved models.[citation required]

Impact and consequences of the Industrial Revolution

- Economic and technical awakening of the West: appearance and extension of industrialism or industrial capitalism.

- Social transformations (bourgeois revolution): increasing complexity of open class societies.

Contenido relacionado

Eunuch

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (film)

Jose Eleuterio Gonzalez