Indo-European languages

The name Indo-European languages refers to the largest family of languages in the world in terms of number of speakers. The Indo-European family, to which most of the languages of Europe, Greater Iran, and South Asia belong, includes more than 150 languages spoken by around 3.2 billion people (approximately 45% of the world's population). Of these, about 1.2 billion correspond to speakers of the Indo-Iranian languages, about 950 million speakers of the Romance languages and about 820 million speakers of the Germanic languages.

Family identification

The French Jesuit Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux was the first to note the similarities between Sanskrit, Latin and Greek, and even between German and Russian, in a memoir sent to the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres de France in 1767. British philologist Sir William Jones is sometimes mistakenly credited with being the first to note the similarities between Sanskrit, Latin, and Greek, for in The Sanskrit Language (1786) assumes that these three languages have a common root and that, furthermore, they may be linked to Gothic, Celtic and Persian languages. Franz Bopp supported this hypothesis by systematically comparing these languages with others and finding multiple cognates. Since the 19th century, scholars have called this family the Indo-Germanic languages. Later the term Indo-European came to be used (except in German). A good example of the Indo-European connection is the enormous similarity discovered between Sanskrit and ancient Lithuanian dialects.

The common ancient language is known as Proto-Indo-European. There is disagreement about the geographical point where (urheimat) originated. The main proposed locations are southern Russia, the Kurgan Oblast, southeastern Ukraine, Armenia or Iran.

This family consists of the following subfamilies: Albanian, Armenian, Baltic, Celtic, Slavic, Germanic, Greek, Indo-Iranian (including Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages), and Italic (including Latin and Romance languages). Two subfamilies that have disappeared today are added to them: the Anatolian (which includes the language of the Hittites) and the Tocharian. From the second half of the 18th century, and throughout the 19th century, historical linguistics and neogrammar tried to gather enough data to show that this apparently diverse set of languages formed part of a single family.

The documents of Sanskrit and classical Greek (the oldest of the Indo-European languages if we except the Hittites, which were not deciphered at that time) present the characteristic forms of the Indo-European languages, which demonstrates the existence of a mother tongue common. The relationships between Sanskrit, Classical Greek and Latin had already been verified towards the beginning of the 19th century.

On the other hand, the grammarians of India elaborated a systematic classification of the elements that constituted ancient Sanskrit. The study carried out in India is completed with another systematic and comparative study of the phonetic and grammatical systems of European languages.

The conclusion of this joint effort was the establishment of the existence of Proto-Indo-European, the mother tongue common to the studied languages, carrying out a reconstruction of the phonetic and grammatical features that it should have. Indo-European is, therefore, a reconstructed language and dated around 3000 BC. C., since around 2000 B.C. C. notable differentiation features are already found between the languages born from it.

In general, the Indo-European languages show some progressive loss of inflection. From what is assumed, Proto-Indo-European was a very inflectional language, as evidenced by other classical languages, such as Sanskrit, Avestan and Greek. Faced with this, some modern languages, after a long evolutionary process, are oriented towards an analytical path, such as English, French and Persian, using prepositional complements and auxiliary verbs instead of nominal declension and verb conjugation.; Others, such as Spanish or Italian, continue to maintain great flexion in their conjugations, tenses, and verbal modes, although they have also lost most of the flexivity in nouns and adjectives that occurred in Latin declensions; while languages like German or Russian, on the other hand, maintain a system of declensions.

To a large extent, the loss of inflectional elements has been the result of a long process that has led to the loss of the final syllables of words; thus many of the Indo-Europeans were shorter than the corresponding Proto-Indo-Europeans. In addition, in other languages the development of new grammatical procedures has taken place and there have been numerous changes of meaning in some specific words.

Common features

Proto-Indo-European has many features that have disappeared from most modern Indo-European languages. In fact, among the Indo-European languages there are grammatical typologies that make them very different from each other, it is not true that all the Indo-European languages currently preserve "similar" with each other, and their phylogenetic relationship is often only accessible through a deep comparative study of them and not by their superficial appearance or the most evident grammatical characteristics. This is due to the fact that these languages have followed markedly different evolutions in each region where they are spoken. However, some almost universal characteristics are recognized in all of them:

- Indo-European languages are highly merging languages.

- Morphos-infective alignment is of nominative-accusative type.

- The grammatical number category is mandatory in both names and pronouns and in the personal forms of the verb. Most languages distinguish only singular and plural, although some languages also possess dual.

- The vast majority of Indo-European languages have some kind of grammatical gender distinction, although some languages such as English restrict this distinction to personal pronouns and other languages, such as Armenian and modern Persian, grammatical gender distinctions have disappeared completely.

Grammatical gender

Sanskrit, Latin, and classical Greek distinguished between three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. Although many more modern Indo-European languages have lost one of these three genders, in Romance languages (with the exception of Astur-Leonese), modern Celtic languages, and Baltic languages, the neuter gender has been assimilated into either the masculine or the feminine. In Dutch and some of the Scandinavian languages, the feminine has disappeared, maintaining the opposition between masculine and neuter. In English, the gender distinction only exists in third person singular pronouns (marginally when the referent is a vehicle or a country she can be used to refer to them), although in Old English gender it also existed in demonstratives and the article. Some modern languages, such as Armenian, have completely lost the gender distinction in both noun and pronoun. between masculine and feminine. Many Indic languages have also lost one of the three genders present in Sanskrit, Hindi-Urdu only differentiates between masculine and feminine, having lost the neuter. In Bengali the loss has gone further and the gender distinction no longer exists, or more exactly is not morphologically productive, although there are residues in the lexicon.

The number of genders in the oldest reconstructible Indo-European is doubtful, since it seems that the oldest Anatolian languages only reflect a distinction between animate and inanimate gender in the adjective. Rodríguez Adrados has proposed that this is the oldest distinction and that the feminine gender also appeared secondarily in the rest of the branches.

Grammatical number

In the earliest stage of the Indo-Iranian, Greek, Slavic, and Celtic languages, there were three possibilities for number: singular, dual, and plural. In the other branches of the family, only two numbers are recorded: singular and plural (marginally in Latin we have vīgintī '20' with a dual ending). Dual has now disappeared from all branches of the Indo-European family, except among the Slavic languages.

The ancestor of all non-Anatolian Indo-European (pIE-II) has been reconstructed as a language in which three numbers would have existed, as in the Indo-Iranian and Greek branches. However, Anatolian only testifies to two numbers, so probably Common Proto-Indo-European (pIE-I) would have been a language with only two numbers, the creation of the dual being a later innovation of non-Anatolian Indo-European.

Grammatical case

The oldest Indo-European languages of all branches of the family (Mycenaean Greek, Hittite, Sanskrit, Latin, Old Irish, Church Slavonic,...) are inflectional languages with a system of 5 to 8 morphological cases. The number of Proto-Indo-European cases is a matter of debate because it is not clear that the maximum case system with nominative, vocative, accusative, genitive, dative, ablative, locative, and instrumental case that we find in Sanskrit goes back entirely to the earliest reconstructible stage. In fact, some authors argue that there are residues of a non-inflectional Pre-Proto-Indo-European that predates Common Proto-Indo-European.

Many modern Indo-European languages, however, have lost much of the case system and conjugation that characterized the older Indo-European languages. Thus, among the Romance languages, derived from Latin, only Romanian preserves a reduced system of cases. The Germanic languages have similarly reduced the number of cases with distinctive forms, with specific case markings on the noun having completely disappeared in English. The Indo-Iranian languages have also suffered a marked decrease in the number of cases. Hindi-Urdu has a system of only three cases: direct or nominative, vocative, and oblique or prepositional. A similar situation occurs in many Iranian languages, such as the Pashto of Afghanistan. Modern Greek has also reduced the number of cases compared to classical Greek, but together with the Slavic languages and Lithuanian it is part of the Indo-European languages with a nominal inflection with the largest number of different cases.

Verb conjugation

The verb system of most branches of Indo-European seems to have undergone more changes than the nominal inflectional system. For this reason, the reconstruction has been based more on endings and morphological marks than on the categories represented.

Prior to the discovery of the Anatolian languages and their kinship with the Indo-European languages, the reconstructed verbal system for Proto-Indo-European was largely based on Greek and Sanskrit. This rebuilt system would consist of:

- Four modes: indicative, subjunctive, imperative and infinitive.

- Two voices: active voice and medium voice.

- Grammatical times derived from three forms of the root, dependent on the grammatical aspect: forms of imperfect, forms of perfect and aoristo forms.

This maximum system, called the Greco-Aryan or Indo-Greek model, was considered the result of late innovations when the Anatolian verbal system became better known. The oldest Indo-European verbal system is, however, difficult to reconstruct, since Anatolian presents a much simpler verbal system and it is therefore impossible to distinguish to what extent it is due to loss of modes or tenses or to what extent the system of languages with a broader conjugation is the result of innovations.

In modern languages, especially European ones, numerous verb forms based on auxiliary verbs and periphrases have appeared. Thus, the Romance and Germanic languages, such as English or German, have lost the synthetic forms of the passive voice and the forms of the perfect, present in ancient languages such as Latin or Gothic, having been replaced with periphrastic forms with the verbs 'to be' and 'have'.

Lexical comparison

The inherited common lexicon is the clearest evidence of genetic kinship between the Indo-European languages. Work based on the comparative method has made it possible to compile dictionaries with several thousand reconstructed terms (preceded by *). The following table gives the reconstructed numerals for different branches of the family:

| proto-IE | PROTO-GERMAN | PROTO-ITÁLICO | PROTO-CELTA | PROTO-BÁLTICO | Old Slav | PROTO-ALBANÉS | PROTO-INDOIRANIO | PROTO-ANATOLIO | PROTO-GRIEGO | PROTO-ARMENIO | PROTO-TOCARIO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ♪ | ♪ | ♪ | ♪ | *oīns | jedvernance | *(ai)aa | *aiwas | *ānt | ♪ | *mik | ♪ Cherēs |

| 2 | ♪ dwō | *twai | *duō | *dwei | *dw(ā)i | dŭva | *dui | *dwā | ♪ dā- | ♪ dwō | ♪ | ♪ |

| 3 | * | *θreiz | * | ♪ | ♪ | trvije | *tre(ye) | ♪ Trayas | ♪tri- | ♪ | ♪erek ♪ | *trey |

| 4 | ♪kwetwor- | *fiθwor | *kwetwōr | ♪kwetwar- | *keturi | četyre | *katur | *ćatwaras | ♪ mewi- | *qettar- | *ć'eyork' | * twerɨ |

| 5 | *penkwe | *fimf- | *kwenkwe | *kwenkwe | ♪penki | pętwin | *penće | *panća | *panku | ♪ | *pink | *pɨnśɨ |

| 6 | *sweks | *seks | *seks | *sweχ | *sweši | šest | ♪skes- | *šwaćs | *hweks | *hweć' | ♪ | |

| 7 | *septm | ♪ | *septem | *seχtan | *septīni | sedmwin | *Septa- | ♪ sapta | ♪ hepta | ♪hewt'm | *š *ptɨ | |

| 8 | ♪3Oktō | *ahtō | *oktō | *oχtū | *aštōni | osmviv | *(ak)te- | *aštā | ♪ haktau | *oktō | ♪ut' | *oktɨ |

| 9 | *newn | *niwun | *newem | *nawan | *newīni | devęt | *nan- | ♪ | ♪nu- | *ennewa | ♪ | ♪ |

| 10 | ♪ from dem | *tehun | ♪ dekem | ♪ dekam | *dešīmt- | desęt | *ðeć- | *daća | *deka | ♪ | *śkkɨ |

Comparison of conjugations

The following tables present a comparison of the conjugations of the thematic present indicative of the verbal root *bʰer - with the meaning of "to carry", and from which they come the English verb to bear, the Greek féro and the Latin "fero" -, as well as its reflections in several early attested IE languages, and their modern descendants or relatives, showing that all languages had an early-stage inflectional verb system.

| Protoindoeuropeo(*)bher- 'to take, bear' | |

|---|---|

| Me. | ♪ bhéroh2 |

| You. | ♪ bhéresi |

| He/she | ♪ bhéreti |

| We (two) | ♪ bhérowos |

| You (two) | *bhéreth1es |

| They (two) | ♪ bhéretes |

| We | ♪ Let's go ♪ |

| You. | ♪ close up |

| They | ♪ bhéronti |

| Subgroup

greater | Hellenic | Indoiranias | Italics | Celtic | Armenian | Germánicas | Baltoeslavas | Albanés | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor | Iran | Baltic | Slavs | ||||||||

| Representative

Old | Greek

Old | Sanskrit

Vedic | Avéstico | Latin | Irish

Old | Armenian

classic | Gothic | Prussian

Old | Ancient Slav

ecclesiastical | Albanés

Old | |

| Me. | phérō | bhárāmi;;ה | barā | ferō | biru; berim | Berem | Baíra | ♪ | berǫ | ♪ | |

| You. | phéreis | bhárasi; معامن | Barahi | fers | biri; berir | Beres | baíris | ♪ | bereši | ♪ | |

| He/she | phérei | bhárati;;ि | baraiti | fert | berid | berē | baíriþ | ♪ | Beret | *berjet | |

| We (two) | - | bhárāvas;;に;。 | barāvahi | - | - | - | Baíros | - | berevě | - | |

| You (two) | phéreton | bhárathas;;स。 | - | - | - | - | baírats | - | Bereta | - | |

| They (two) | phéreton | bháratas; conducive | baratō | - | - | - | - | - | Berete | - | |

| We | phéromen | bhárāmas;;の。 | barāmahi | ferimus | bermai | beremk close | baíram | *beramai | ♪ | ♪ Cover me ♪ | |

| You. | phérete | bháratha;;;; | baraθa | fertis | beirthe | berēk vaginal | baíriþ | *beratei | Berete | *berjeju | |

| They | phérousi | bháranti;;ה | bar ISSN | ferunt | berait | ♪ | baírand | ♪ | ♪ | *berjanti | |

| Representative

modern | Greek

modern | Hindi-Urdú | Persian | Spanish | Irish | Armenian

East | Armenian

Western | German | Lithuanian | Slovenian | Albanés |

| Me. | fertile | bharūm;;;の | {mi}baram | [whispering] | beirim | berum em | g'perem | {ge}bäre | beriu | Bertem | bie |

| You. | férnis | bharē; | {mi}bari | {con}ferences | beirir | berum es | g'peres | {ge}bierst | beri | béreš | bie |

| He/it | ferni | bharē; | {mi}barad | {conference} | beireann; beiridh | berum ē | g'perē | {ge}biert | Beria | bére | bie |

| The two of us. | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | beriava | Bergamo | - |

| You two | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | beriata | Breathe | - |

| They're two. | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Beria | Breathe | - |

| We | férnume | bharēm;;;に | {mi}barim | We'll be | beirimid; beiream | berum enk childhood | g'perenk urge | {ge}bären | Beriame | Béremo | biem |

| You. | férnete | bharo;;;; | {mi}barid | {with}fers | beireann sibh; beirthaoi | berum ek cerebral | g'perek absent | {ge}bärt | Beriate | Bérès | bini |

| They | fernun | bharēm;;;に | {mi}barand | They don't. | beirid | berum en | g'peren | {ge}bären | Beria | bérejo/berENCIA | Good. |

Classification of Indo-European languages

Traditionally, Indo-European was classified into two groups: satem languages and centum languages, which received those names depending on whether the Proto-Indo-European velar phoneme series /*k, *g, *gh/ palatalized (*kntom '[the number] 100' is in Avestan satem) or not (*kntom gave in Latin centum). However, today hardly any importance is attached to the change (one among many), nor is it believed to be a solid criterion that adequately classifies the Indo-European languages. In fact, several classifications that try to reconstruct the cladistic tree of Indo-European languages do not even consider the satem languages as a proper branch. This suggests that palatalization spread between what were different branches of the family.

The first branch to diverge from the common stem was the Anatolian branch and somewhat later the Tocharian branch, both branches are now extinct (no currently spoken descendants). These two branches do not present the typical palatalization of satem languages, even though Tocharian is an "eastern" branch. In fact, it is the only Eastern language that does not palatalize, which suggests that the palatalization on which the centum / satem division is based is relatively late. The remaining subdivisions are somewhat more disputed, although it seems clear that Greek, Armenian, and probably other Paleo-Balkan languages would form a subdivision together. This Greco-Armenian branch includes both satem languages and centum languages, which is why the division satem-centum is not adequate, since neither of the two subdivisions would be proper cladistic branches.

Main subdivisions

The internal relationships between these top-level groups are somewhat more complicated and contentious, and there are still minor discrepancies. For example, although a special relationship between the Greek group and some Paleo-Balkan languages (particularly Armenian) is universally recognized, it is not clear, for example, whether the Indo-Aryan languages were formed by a division of a hypothetical Proto-Indo-Slavic or, conversely,, should be considered the result of a split from a hypothetical Proto-Indo-Greek. And similar problems are found with the Germanic languages, the Slavic languages, the Celtic languages or the Italic languages.

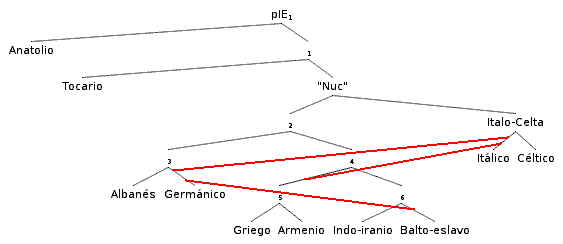

Recently three internal classification attempts have appeared grouping the above basic subgroups: The Gray-Atkinson phylogenetic tree (The 'New Zealand' family tree, 2003), the tree Ringe-Warnow-Taylor phylogenetic tree (The 'Pennsylvania' family tree, 2002) and the Gamallo-Pichel-Alegria phylogenetic tree (Measuring Language Distance of Indoeuropean Languages, 2020). The first is strictly based on shared and substituted lexicon, the second is based on phonological and morphological isoglosses, the third on Proto-Indo-European derived isoglosses and lexicon. Although both classifications have some common points, they also differ in important ways in other details. Branches marked with (†) correspond to extinct branches or languages that no longer had native speakers. The Gray-Atkinson tree has the following form:

| proto-IE1 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Gamallo-Pichel-Alegria tree, which instead uses lexicostatic methods and linguistic evolution parameters, has the following form:

| proto-IE1 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Ringe-Warnow-Taylor tree, which leaves out the Germanic languages, since considering them implies that there is no best-fit (i.e., phylogenetically perfect) tree, has the following form:

| proto-IE1 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In a later work Ringe-Warnow-Evans-Nakhleh used 292 characters (comparison parameters) and used phylogenetic networks instead of trees (under the hypothesis of homoplasy, independent development and others) arriving at a phylogenetic network very similar to the Gamallo-Pichel-Alegria tree, which included three "branches" Contact (in red):

Satem languages

There are doubts that the satem languages constitute a valid phylogenetic unit within Indo-European, as was once thought. If the phylogenetic trees proposed by Ringe and Warnow are correct, the satem languages would constitute a phylogenetic unit (unlike the centum languages, which would be the rest of the languages that would not form a valid phylogenetic group).

- Southern Balkan Languages (Frigio-Armenian group): Armenian, Frigio (†), peonio (†).

- Northern Balkan Languages (Daco-trace group, Albanian): Albanian, Dacius (†), Trace (†).

- Baltic languages: Old Prusian (†), Latvian, Lithuanian

- Indoirania languages:

- Indoor languages:

- ancient and medium indoiranio: Sanskrit, pr. (†).

- modern indoario: assamés, bengalí, cingalés, guyaratí del norte, guyaratí del sur, hindi-urdu, maratí, nepalí, panyabí central, romaní, sindhi, cachemir, bhili, chatisgarí, oriya, kumhali

- Iranian languages:

- Antiguas: Old Persian (†), avéstico (†), medo (†), escita (†).

- Media: sogdiano (†), kotanés (†), bactriano (†), childbirth (†), pahlavi (†), mean Persian (†).

- Modern: beluche (baluchi), kurdo, grass, modern Persian, tayiko, osetio/iron/digorés

- Drugs

- Nuristan languages

- Indoor languages:

- Slavic languages

- Southern Slaves: Bosnian, Bulgarian, Croatian, Slovenian, Macedonian, Serbian, former ecclesiastical Slave (†).

- Western Slaves

- Polish-hunting: Polish, Polish (†), silesian, casubio

- Other: Czech, Slovak, deaf (sorbic, luscious).

- Eastern Slaves: Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian, Ruthenian (†), Russian.

Centum languages

The centum languages do not constitute a valid phylogenetic unit within Indo-European, as was once thought. Since among these languages there is both the Anatolian group that was the first branch to differentiate from Indo-European and languages that would only differentiate from each other later. In other words, it would not be possible to reconstruct a "protocentum" that by diversification would have given rise to the centum languages that were different from the common Proto-Indo-European. In this sense, the classification in centum languages obeys more to accidental and conventional facts than to a strict linguistic fact. The list of centum languages is as follows:

- Anatolia languages (†): Hitita (†), lidio (†), licio (†), luvita (†), pisidio (†), sidético (†).

- Celtic languages

- Continental Celtic languages: Galo (†), celtiber (†), lepontico (†).

- Gothic languages (gaelics): Manés (†), gaélico irlándes, gaélico escocés

- British languages: Corn (†), Breton, Welsh.

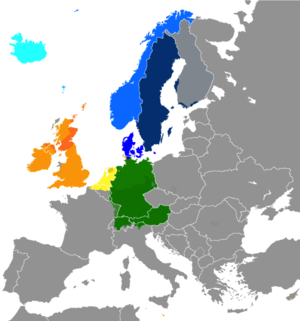

- Germanic languages

- Western Germanic languages:

- English Language: English, Scottish, French,

- Lower Germanic languages: under German, Dutch, afrikaans, limburgués

- High-Germanic Languages: German Standard (German High), Luxembourg, Yiddish

- Eastern Germanic languages: Gothic (†), burgundy (†), vándalo (†).

- Nordic languages:

- Eastern Nordic languages: Icelandic, feroés, neonoruego (nynorsk), norn (†), Norwegian (bokmål, riskmål), dalecarniano,

- Western Nordic Languages: Danish, Swedish, ancient gútnico (†).

- Western Germanic languages:

- Hellenic languages: Classic Greek, modern Greek.

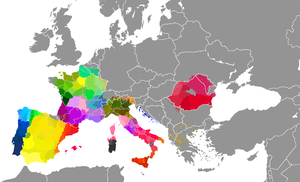

- Italic languages:

- Osco-umbra languages (†): Osco (†), umbro (†), piceno (†)

- Latin-faliscan languages: Falisco (†), sículo (†), Latin.

- Romance languages

- Western romance languages

- Iberorromance languages: Spanish, Galician and Portuguese, Asturleonés, Aragonese

- Occitance languages: Catalan, West.

- Galloromance languages: French and languages of oïl, franc-provenzal.

- Renewed languages: Romanche, friulan, ladino.

- Galician languages: Ligur, piamontés, lombardo, emiliano-romañol, véneto.

- Mozárabe (†)

- Island romance languages: Sardo, sassars

- Eastern Romance languages

- Italorromances languages: Italian standard, Romanesque, Neapolitan, Sicilian, Corso-gallurés.

- Balkan languages: Rumano, arrumano, meglenorrumano, istrorrumano

- Dalmatian (†).

- Western romance languages

- Romance languages

- Curriculum languages (†): Tocario A (†), tocario B (†).

- Lusitano (†).

Kinship with other languages

There is currently no incontrovertible evidence that Indo-European languages show a clear relationship to languages of other families, although there are a number of tentative proposals that suggest that it is possible to recognize the distant relationship of Indo-European languages to other language families of Eurasian. The Nostratic hypothesis (Pedersen, Ilich-Svítych and Dolgopolski) and Greenberg's Eurasian hypothesis hold that the Uralic, Afroasiatic and other languages show a recognizable relationship to Proto-Indo-European and that it is possible to partially reconstruct the proto-language from which these families descend..

However, these hypotheses have met with a high degree of criticism and are not currently generally accepted, although supporters of these hypotheses have continued comparative work in favor of it.

Contenido relacionado

Sociolinguistics

Hmong–Mien languages

Official language