Indian architecture

The architecture of India is rooted in its history, culture and religion. Indian architecture progressed over time and assimilated the many influences that emerged as a result of India's global history with other regions of the world throughout its more than two millennia of existence. The architectural methods practiced in India are the result of the examination and implementation of established construction traditions and external cultural interactions. The oldest monuments in India are of a recent era compared to those of Chaldea and Egypt and are attributed at most to the 5th century. > before our era, they are religious and correspond to the Brahmanic and Buddhist religions dominant there. There are no known ancient palaces in Indian architecture, since the oldest ones date back to the XV century, the previous ones having been built with of low quality and those found of Indian art (which are not Muslim art) are very scarce. The same goes for tombs or funerary monuments that are not religious.

Although ancient, that Eastern tradition has also incorporated modern values as India became a modern nation-state. The economic reforms of 1991 further strengthened India's urban architecture as the country became more integrated into the global economy. The traditional Vastu Shastra remains influential in Indian architecture during the contemporary era.

The most common types in Indian architecture are:

- the underground temple along with the monolithic,

- the Stupa or Tope along with the vihara,

- the paid outdoors,

- the Gopura,

- the sikhara,

- the doors (dvara, torana) and commemorative columns.

Indus Valley Civilization (3300 BC - 1700 BC)

The Indus Valley Civilization (3300-1700 BC) covered a large area around the Indus River Basin and beyond. In its maturity phase, from ca. 2600-1900 BC. C., produced several cities marked by great uniformity within and between sites, such as Harappa, Lothal and Mohenjo-daro, a UNESCO World Heritage site. The civic and urban and engineering aspects of these cities are notable, but the design of the buildings is "of a surprising utilitarian character." There are granaries, drains, watercourses and cisterns, but no palaces or temples have been identified, although the cities have an elevated and fortified central "citadel". Mohenjo-daro has wells that may be the ancestors of the Baori. As many as 700 wells have been discovered in a single section of the city, leading scholars to believe that "cylindrical brick-lined wells" were invented by the Indus Valley civilization.

Architectural decoration is extremely minimal, although there are "narrow pointed niches" within some buildings. Most of the art found is in miniature forms such as seals, and mainly in terracotta, but there are very few sculptures of larger figures. In most sites, baked mud brick (not sun-baked as in Mesopotamia) is used exclusively as a building material, but some such as Dholavira are in stone. Most houses have two floors, with very uniform sizes and floor plans. The large cities declined relatively quickly, for unknown reasons, leaving behind a less sophisticated village culture.

Mahajanapadas (600-320 BC)

Urban architecture

Since the time of the Mahajanapadas (600-320 BC), walled and moated cities with large gates and multi-story buildings that consistently used arched windows and doorways, and which made an intense use of wooden architecture. The Sanchi reliefs, dating from the I century BC. C. to the century I d. C., already show representations of cities such as Kushinagar or Rajagriha that show them as splendid walled cities during the time of Buddha (VI century BC), as in the Royal procession leaving Rajagriha or the war over the relics of Buddha. Those views of ancient Indian cities were based on the understanding of ancient Indian urban architecture. Archaeologically, that period corresponds in part with the Northern Black Polished Ware culture. Geopolitically, the Achaemenid Empire began occupying the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent from ca. 518 BC C.

Various types of individual dwellings from the time of the Buddha (c. 563/480 or c. 483/400 BC), resembling huts with doors decorated with chaitya, are also described in the Sanchi reliefs. Particularly, the Jetavana at Sravasti, shows the Buddha's three favorite residences: the Gandhakuti, the Kosambakuti and the Karorikuti, with the Buddha's throne in front of each. The Jetavana Garden was presented to the Buddha by the rich banker Anathapindika, who bought it for so many pieces of gold that it would cover the surface of the ground. That is why the foreground of the relief is shown covered with ancient Indian coins (karshapanas), as shown in a similar relief at Bharhut. Although the Sanchi reliefs date back to the 1st century I a. C., the scene portrayed takes place during the time of the Buddha, four centuries before, which is considered an important indication of the construction of traditions in those early times.

Religious architecture

Buddhist caves

During the time of Buddha (c. 563/480 or c. 483/400 BC), Buddhist monks also had the custom of using natural caves, such as the Saptaparni Cave, southwest of Rajgir, Bihar. Many believe that it was the site where Buddha spent some time before his death, and where the first Buddhist council after Buddha's death (paranirvana) was held. Buddha himself also used the cave of Indrasala for meditation, beginning a tradition of using caves, natural or man-made, as religious retreats, which would last over a millennium.

Monasteries

[[File:Jivakarama oblong communal hall.jpg|thumb|Jivakarama monastery vihara. Oblong communal hall (remains), 6th century BC. c. The earliest monasteries, such as the Jivakarama vihara in Rajgir, Bihar, were built from the time of the Buddha, in the 6th or 5th centuries BC. The initial Jivakarama monastery consisted of two long parallel and elongated corridors, large dormitories where the monks could eat and sleep, in accordance with the original regulations of the samgha, without private cells. Other rooms were later built, mostly elongated and oblong buildings, reminiscent of the construction of several of the Barabar caves. It is said that Buddha was once treated at the monastery, after being wounded by Devadatta.

Stupas

[[File:Stupas-Original-00020.jpg|thumb|right|The stupas at Piprahwa are some of the earliest surviving stupas.]]

Religious buildings in the form of a Buddhist stupa, a dome-shaped monument, began to be used in India as memorials associated with the preservation of sacred relics of Buddha. The relics of Buddha were divided among eight stupas, in Rajagriha, Vaishali, Kapilavastu, Allakappa, Ramagrama, Pava, Kushinagar and Vethapida. The Piprahwa stupa also appears to have been one of the first to be built. Protective railings—consisting of posts, crossbars and a coping—became in a security feature surrounding a stupa. Buddha himself had left instructions on how to pay homage at stupas: "And whoever puts garlands or places sweet perfumes and colors there with a devout heart, he will reap benefits for a long time." This practice would lead to the decoration of stupas with stone carvings of flower garlands in the Classic period.

Classical period (320 BC-550 AD)

Monumental stone architecture

The next wave of construction, based on the first examples of true stone architecture, appears with the beginning of the Classic period (320 BC-550 AD) and the rise of the Mauryan Empire. The capital city of Pataliputra was an urban wonder described by the Greek ambassador Megasthenes. The remains of monumental stone architecture, with strong Achaemenid and Greek influence, can be seen in the numerous artifacts recovered from Pataliputra, such as the Pataliputra capital. This cross-fertilization between different artistic currents that converged on the Indian subcontinent produced new forms that, while preserving the essence of the past, managed to integrate selected elements of new influences.

The Indian Emperor Ashoka (r. 273-232 BC) established Ashoka Pillars throughout his kingdom, usually next to Buddhist stupas. According to Buddhist tradition, Ashoka had recovered Buddha's relics from previous stupas (except the Ramagrama Stupa) and erected 84,000 new stupas to distribute the relics throughout India. Indeed, many stupas are thought to date originally from Ashoka's time, such as at Sanchi or at Kesariya, where he also erected pillars inscribed with him, and possibly at Bharhut, Amaravati or Dharmarajika, in Gandhara.

Ashoka also built the initial Mahabodhi temple, in Bodh Gaya, around the Bodhi tree, including masterpieces such as the Diamond Throne (Vajrasana). He is also said to have established a chain of hospitals across the Mauryan empire in 230 BC. C. One of Ashoka's edicts says: "Everywhere, King Piyadasi [Ashoka] erected two types of hospitals, hospitals for people and hospitals for animals. Where there were no healing herbs for people and animals, he ordered that they be purchased and planted. "Indian art and culture have absorbed foreign impacts to varying degrees and are much richer for that exposure.

During the Mauryan Empire (ca. 321-185 BC), many fortified cities with stupas, viharas, and temples were built. Architectural creations of the Mauryan period, such as the city of Pataliputra or Ashoka's pillars, stand out among his achievements, and are often compared favorably with the rest of the world at the time. Commenting on Mauryan sculpture, archaeologist John Marshall noted the "extraordinary precision and accuracy which characterizes all Mauryan works, and which has never been, we dare say, surpassed even by the most refined workmanship of Athenian buildings.".

An early, 6 m diameter, with parasol falling on the side. Chakpat, near Chakdara. Probably from the Maurya era, the third century a. C.

Ruins of the pillar room on the Kumrahar site, in Pataliputra

Pataliputra polished stone maurya

Rediscovery in 1905 of Ashoka pillar in Sarnath

Caves carved into the rock

The architecture carved in the rock of India, also rough architecture, refers to the buildings excavated or sculpted in caves, caves or rocky walls by the ancient civilizations of India, the most varied and found in greater abundance in that country than in any other country in the world. The architecture carved on the rock is the practice of creating a building carving on the solid natural rock, removing the rock that does not form part of the building, until the only rock remains according to the architectural elements of the excavated interior. The Indian architecture carved on the rock is mostly religious.

There are more than 1500 well-known buildings carved on the rock in the country, most adorned with exquisite stone carvings and many of them house works of art of world importance. These ancient and medieval buildings represent significant achievements of structural engineering and handicrafts.

In India, caves have been regarded from ancient times as sacred places, a condition that kept caves enlarged or made by man, as sacred as the natural caves. The sanctuary in all Indian religious buildings, even in the independent ones, was designed to have in it the same feeling as in a cave, being generally small and dark dependencies, without natural light. The oldest architecture in rock is located in the caves of Barabar, in the state of Bihar, which were built around the century B.C. and personally dedicated by Ashoka ca. 250 BC. They already show an amazing level of technical skill, being the extremely hard granite rock cut according to geometric and polished shapes to get a mirror-type finish. Originally, there would probably be buildings of associated wood that would have deteriorated over time and of those that left no remains. Numerous reliefs have been found in rock, relief sculptures carved on the faces of rock, outside the caves or elsewhere.

Probably because of the fall in the century a. C. of the Maurya Empire and the persecutions of Buddhism under Pushyamitra Sunga, many Buddhists moved to the plateau of the Decan under the protection of the Andhra dynasty, thus changing the effort to build caves to western India: an enormous effort to create religious caves (usually Buddhists or Jainists) continued until the century B., which culminated with the caves of Karl. These caves generally followed an absidial plant by setting a stupa on the back for the chaityas, and a rectangular plant with surrounding cells for the viharas. Numerous donors provided funding for the construction of these caves and left donative inscriptions, including some lay people, clergy members, government officials and even foreigners as Yavanas (indoGegos), representing approximately 8% of all registrations.

Historically, the craftsmen carried forward elements of wood design in their temples carved on the rock: skilled artisans carved the rocks to imitate the texture, the veins and the structure of the wood. The oldest temples include Bhaja caves, Karla caves, Bedse caves, Kanheri caves and some of the Ajanta caves. The relics found in these caves suggest a connection between the religious and the commercial. It is known that Buddhist missionaries would have accompanied traders on the busy international trade routes through India. Some of the most sumptuous cave temples, commissioned by wealthy merchants, included pillars, arches and elaborate facades. They were made during the period when maritime trade thrived between the Roman Empire and Southeast Asia.

The construction of caves would disappear after the century AD, possibly due to the emergence of Mahayana Buddhism and the intense architectural and artistic production associated with Gandhara and Amaravati. The construction of caves will revive briefly in the century AD, with more sophisticated sizes, with the magnificent achievements of Ajanta and Estora. The monolithic temple of Kailash is considered the cenit of this type of construction, the last and most spectacular temple excavated on the rock.

Finally the caves will disappear widely when Hinduism replaced Buddhism in the subcontinent, and the temples exempted became more frequent. Some examples continued in caves until the centuryXII, but the architecture carved in rock became almost entirely of structural nature. That is, the rocks were cut into blocks and used to build independent buildings.

The architecture carved in rock also developed with the appearance of baoris in India, dating from 200 to 400 d. C. Subsequently, the construction of wells was carried out in Dhank (550-625) and phased ponds in Bhinmal (850-950).

- Examples of caves carved in rock

Jainite Cave-monastery in the caves of Udayagiri and Khandagiri (sixth century BC)

Jainite monuments Chitharal, century I a. C.

The great chaitya in the caves of Karla, Maharashtra, ca. 120 a. C.

Gautamiputra vihara in the caves of Nasik, built in the second century B.C. by the Satavahana dynasty

The caves of Ajanta are 30 Buddhist monuments excavated in caves, built under the vakatakas, ca. century V d. C.

Decorated stupas

Stupas were soon richly decorated with sculptural reliefs, after the first attempts at Sanchi Stupa No. 2 (125 BC). Sculptural decorations and scenes from the life of Buddha were used at Bharhut (115 BC), Bodh Gaya (60 BC), Mathura (125–60 BC), and again at Sanchi for the elevation of the toranas (span style="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">I BC- century I AD) and then Amaravati (1st-2nd centuries). The decorative adornment of stupas also had considerable development in the north-west of the Gandhara area, with decorated stupas such as the Butkara stupa (& #34;monumentalized" with Hellenistic decorative elements from the II century BC) or the Loriyan Tangai stupas (century II BC). Stupa architecture was adopted in Southeast and East Asia, where it became a prominent Buddhist monument used to enshrine sacred relics. Indian entrance arches, the torana, reached East Asia with the spread of Buddhism. Some scholars maintain that the torii derives from the torana gates at the Buddhist historical site of Sanchi (3rd century BC – 11th century).

Stitch No.2 of Sanchi, the oldest stupa known with important displays of decorative reliefs, c. 125 BC.

East gate and Bharhut stupa rails. Sculpted rails: 115 BC, toranes: 75 BC.

The Great Stupa in Sanchi. Decorated windows built from the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD.

Amaravati Stupa, I-II century

Exempt temples

The temples—built on elliptical, circular, quadrilateral or apsidal plans—were initially built using bricks and wood. Some wooden temples with wattle and bush may have preceded them, but none remain to this day.

Circular temples

Some of the oldest free-standing temples may have been circular, such as the Bairat temple in Bairat, Rajasthan, consisting of a central stupa surrounded by a circular colonnade and a surrounding wall. It was built during the time of the emperor Ashoka and two of Ashoka's minor rock edicts were found near him. Ashoka also built the Mahabodhi temple in Bodh Gaya ca. 250 BC C., also a circular building, to protect the Bodhi tree under which the Buddha would have found enlightenment. Depictions of this early temple building are found in a relief from 100 BC. C. carved on the railing of the stupa at Bhārhut, as well as at Sanchi. From that period remains the Diamond Throne, an almost intact slab of sandstone decorated with reliefs, which Ashoka had established at the foot of the Bodhi tree. These Circular type temples were also found in later rock-cut caves, such as in the Tulja or Guntupalli caves.

- Circular temples

Remains of the circular temple of Bairat (ca. 250 BC), with a central estupa

Relieve of a circular temple in Bharhut (ca. 100 B.C.)

Hindu temple dedicated to Shiva represented in a coin of the 1st century BC.

Relieve of a temple of several plants, century II, Ghantasala stupa

Apsidal temples

Another early freestanding temple in India, this time apsidal in form, appears to be Sanchi Temple No. 40, also dating to the 3rd century BC. C. It was an apsidal wooden temple built on a high rectangular stone platform, 26.52x14x3.35 m, with two flights of stairs arranged in the east and west sides. The temple was burned down sometime in the 2nd century BC. C. This type of apsidal building was also adopted in most of the caves (Chaitya-grihas), such as in the Barabar caves, from the 3rd century BC. C., and in most of the later caves, with side and then frontal entrances. An independent apsidal temple is still preserved, although in a modified form, the Trivikrama temple in Ter (Maharashtra).

- Abidial temples

Illustration of the temple n.o 40 in Sanchi, dated in the third century a. C.

Temple of Trivikrama in Ter: an ancient Buddhist temple absidial, at the front of which was later added a Hindu square mandapa

Abidial Temple of Chejarla, also later converted to Hinduism

Truncated pyramidal temples

The truncated pyramid-shaped temple is thought to have derived from the design of the stepped stupas that had developed in Gandhara. The Mahabodhi temple at Bodh Gaya is an example of this type, adapting Gandhara design from a succession of steps with niches that house images of Buddha, alternating with Greco-Roman pillars, as seen in the Jaulian stupas. The building is crowned by the shape of a hemispherical stupa crowned by finials, forming a logical elongation of the stepped Gandhara stupas.

Although the current construction of the Mahabdhodi temple dates back to the Gupta period (5th century AD), the so-called “Mahabhodi Temple plaque”—discovered in Kumrahar and dated between 150 and 200 AD. based on its dated Kharoshthi inscriptions and the combined finds of Huvishka coins—suggests that the pyramidal building already existed in the 2nd century AD. C. This was confirmed by archaeological excavations at Bodh Gaya.

This truncated pyramid design also marked the evolution from the aniconic stupa, dedicated to the cult of relics, to the iconic temple in which there were already numerous images of Buddha and Bodhisattvas. This design was very influential in the development of later Hindu temples.

Square prostyle temples

Later, the Gupta Empire also built free-standing Buddhist temples (following the example of the great cave temples of Indian rock architecture), such as Temple No. 17 at Sanchi, dating from the early period. Gupta (5th century AD). It consists of a flat-roofed square cell or sanctuary with a portico and four pillars. From an architectural perspective, it is a classical-looking tetrastyle prostyle temple. The interior and three sides of the exterior are smooth and have no decoration, but the front and pillars are elegantly carved, unlike temples in II century cave excavated in the rock of the Nasik Caves. The universities of Nalanda and Valabhi, which housed thousands of teachers and students, flourished between the 4th and 8th centuries.

End of the classical period

This period ends with the destructive invasions of the Alchon Huns in the VI century. During the rule of the Hunnic king Mihirakula, more than a thousand Buddhist monasteries throughout Gandhara are said to have been destroyed. The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, writing in 630, explained that Mihirakula ordered the destruction of Buddhism and the expulsion of the monks. He reported that Buddhism had declined drastically and that most monasteries were deserted and left in ruins. Gandhara Buddhist art, particularly Greco-Buddhist art, essentially became extinct in that period. The invasions marked the beginning of the decline of Buddhism in India.

Although it only lasted a few decades, the invasions had long-term effects on India, and, in a sense, put an end to classical India. Shortly after the invasions, the Gupta Empire, already weakened by those invasions and after the rise of many local rulers, it ended as well. After these invasions and the collapse of the Guptas, a time of some disorder followed in northern India, with the emergence of numerous smaller Indian powers.

Early Middle Ages (550-1200)

The architecture of the temples in South India is already shown as a distinct tradition during the VII century.

The architecture of the Māru-Gurjara temple originated sometime in the 6th century in, and around, areas of Rajasthan. Māru-Gurjara architecture shows the deep understanding of constructions and refined skills of Rajasthani craftsmen of the bygone era and has two prominent styles: Maha-Maru and Maru-Gurjara. According to M. A. Dhaky, the Maha-Maru style developed mainly in Marudesa, Sapadalaksha and Surasena and in parts of Uparamala, while the Maru-Gurjara would have originated in Medapata, Gurjaradesa-Arbuda, Gurjaradesa-Anarta and in some areas of Gujarat. Scholars such as George Michell, M.A. Dhaky, Michael W. Meister and U.S. Moorti believe that Māru-Gurjara temple architecture is entirely Western and that it differs quite a bit from North Indian temple architecture. There is a connection between Māru-Gurjara architecture i> and the architecture of the Hoysala temple. In both styles, the architecture is treated in a sculptural manner. Regional styles include Karnataka architecture, Kalinga architecture, Dravidian architecture, Western Chalukya architecture and Badami Chalukya architecture.

The temple of southern India consists essentially of a sanctuary of square chambers surmounted by a superstructure, a tower or spire, and a portico or hall with adjoining pillars (maṇḍapa or maṇṭapam ), enclosed by a peristyle of cells within a rectangular patio. The external walls of the temple are segmented by pilasters and have niches that house sculptures. The superstructure or tower above the sanctuary is of the kūṭina type and consists of an arrangement of floors that gradually retreat in a pyramidal shape. Each floor is outlined by a parapet of miniature shrines, square in the corners and rectangular with barrel-vaulted ceilings in the center.

The temples of northern India already showed in the X century a greater elevation of the walls and had towers Richly decorated temples were built in central India, including those in the complex at Khajuraho. Indian traders brought Indian architecture to Southeast Asia via various trade routes. Characteristics of temple architecture in India were grandeur of construction, the beautiful sculptures, the delicate carvings, the high domes, the gopuras and the wide patios. Prominent examples are the Lingaraj temple in Bhubaneshwar (Odisha), the Suria temple (Konark)Suria temple in Konark (Odisha) or the Brihadeeswarar temple in Thanjavur (Tamil Nadu).

The temple carved in the rock of the Shore Temple of the temples in Mahabalipuram, 700-728

The ruins of the Nalanda Mahavihara in Nalanda.

The Kandariya Mahadeva temple in the Khajuraho temple complex in the shikhara style, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Teli ka Mandir, an 8th-century Hindu temple built by the emperor pratihara Mihira Bhoja

The temple of Galaganatha in the Pattadakal complex is an example of the architecture of the chalukya of Badami

Central sanctuary of the temple of the Sun of Martand, dedicated to the deity Surya.

The temple of Jagannath in Puri, one of Char Dham (the four main spiritual centers of Hinduism)

The granite gopuram (torre) of the Brihadeeswarar temple in Thanjavur, which was completed in 1010 by the Raja Chola I.

Rani ki vav is a Baori, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan.

Jain temple complex wall, Deogarh

Late Middle Ages (1100-1526)

Temple of Suria in Konark, Orissa, built by Emperor Narasimhadeva I (1238-1264) of the eastern Ganga dynasty, is now declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO

Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) in ruins, built by the Kakatiya dynasty

Virupaksha Temple, Raya Gopura (main tower over entrance door) in Hampi

Elephants in the Bucesvara temple

Vijayanagara marketplace in Hampi, along with the sacred tank located on the side of Krishna temple.

Stone temple car in Vitthala temple, in Hampi

Hoysala architecture

Today's architecture is the style of the buildings developed during the 11th and 14th centuries under the control of the Hoysala Empire, in the region known as Karnata, today Karnataka, state southwest of India. There are many temples, large and small, built in the centuryXIII which are preserved as a sign of the architectural style of the Hoysala, among others: the temple of Chennakesava, in Belur; the temple of Hoysaleswara, in Halebidu; and the temple of Kesava, in Somanathapura. A characteristic of the architecture of today's temples is its attention to detail and the technical skill of the artisans, which is also seen in the temples of Belavadi, Amrithapura and Nuggehalli. Studies on the style reveal a low indoriatic influence while the impact of the style of southern India is more appreciable.

Today one of the main tourist destinations in Karnataka, the hollow temples allow you to know the Hindu medieval architecture of the tradition. That tradition was born in the centuryVIII under the patronage of the Chalukya dynasty of Badami, it developed during the centuryXI by the western chalukyas of Basavakalyan and finally, it became an independent style in the centuryXIIDuring the reign of the Hoysala. Inscriptions in medieval canars are shown incisas in stones of the temples, giving details about these and information leftover the Hoysala dynasty.

On April 15, 2014, the "Sacred Conjuncts of the Hoysala" was registered in the Indicative List of India, a step before being declared a World Heritage Site, in the category of cultural good (no. ref 5898). Approximately 100 temples of the Hoysa period last today. The nomination includes two groups of monuments (in Belur and Halebidu) richly decorated with sculptures and stone carvings, built by followers of Vaishnavism, Shaivism and Jainism. The Chennakeshava temple in Belur remains an important place of pilgrimage.

For me, enjoying the temples of the late chalukya dynasties and Hoysala is one of the great pleasures of life. I love these temples because their designs are logical and natural, because their architecture is naive, because their execution is rich...Gerard Foekema, Preface of the Complete guide to Hoysala temples

- Examples of todaysala architecture

Shrine starry plant in Chennakeshava temple in Aralaguppe

The temple of Kesava in Chennakeshava complex in Belur has been active since its foundation

Kedaresvara Temple in Balligavi (XI century, expanded in 1131)

Brahmeshvara Temple in Kikkeri (finished in 1171)

Kedareshwara Temple in Halebidu

Temple of Chennakesava, in Somanathapura, consecrated in 1258

Vijayanagara architecture

The vijayanagara architecture (in canars: ) is the style of the constructions developed during the Hindu government of the Vijayanagara Empire (1336-1565). The empire ruled South India, from its real capital in Vijayanagara, on the banks of the Tungabhadra River in the current state of Karnataka. The empire built temples, monuments, palaces and other buildings throughout southern India, with a greater concentration in its capital. The monuments in, and around Hampi, in the Principality of Vijayanagara, are listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

In addition to building new temples, the empire added new buildings and made modifications to hundreds of temples throughout southern India. Some buildings in Vijayanagara are from the pre-vijayanagara period. The temples of the Mahakuta hill are of the time of the Empire of the Western Chalukya. The region around Hampi had been a popular place of worship for centuries before the Vijayanagara period, dating the oldest records of 689, when it was known as Pampa Tirtha, by Pampa, the local god of the river.

There are hundreds of monuments in the central area of the capital city. Of these, 56 are protected by UNESCO, 654 monuments are protected by the government of Karnataka and another 300 are awaiting protection.

The architecture of the Vijayanagara era (1336-1565) was a notable building style developed by the Vijayanagar empire that ruled most of southern India from its capital at Vijayanagara, on the banks of the Tungabhadra River, in present-day India. Karnataka. The architecture of the temples built during the Vijayanagara period had elements of political authority. This gave rise to the creation of a distinctive imperial style of architecture that was prominent not only in temples but also in administrative buildings throughout the Deccan. The Vijayanagara style is a combination of the styles of the Chalukya, Hoysalas, Pandya and Cholas that evolved early in the centuries in which these empires dominated and are characterized by a return to the simplistic and serene art of the past.

Early Indo-Islamic architecture

After the Muslim conquests and their establishment in the region, the first examples of Indo-Islamic architecture came to light. Few examples survive from the period, most notably the Qutb complex, which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993. The complex consists of the Qutab Minar, begun in 1193 by Qutb-ud-din Aibak—the first Muslim ruler in the Delhi area, and founder of the Delhi Sultanate—but could only complete its base. His successor, Iltusmish, added three more floors. The work was completed in 1368 by Firuz Shah Tughluq, and since then, with its 72.5 m height, it has been the tallest brick minaret in the world. Other monuments built by successive sultans of Delhi remain, such as the Alai Minar, a minaret that was intended to double the size of the Qutb Minar and was commissioned by Alauddin Khilji, although it was never completed. Other examples include the Tughlaqabad fort and the Hauz Khas complex.

Early modern period (1500-1858)

Rajput architecture

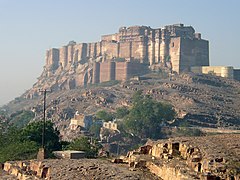

Rajput architecture represents different types of buildings, which can generally be classified as secular or religious. The buildings that are preserved, of various scales, are temples, forts, baoris, gardens and palaces. The forts were built especially for military and defense purposes due to Islamic invasions.

During the 17th century, Mughal architecture and Mughal painting influenced the art and architecture styles of the indigenous people rajput.

Rajput architecture continued well into the 20th and 21st centuries, as the rulers of the princely states of British India commissioned vast palaces and other buildings, such as the Albert Hall Museum, Lalgarh Palace, and Umaid Bhawan Palace.. These large buildings usually also incorporated European styles, a practice that eventually led to the Indo-Saracenic style.

Built during the 15th century by Rana Kumbha, the walls of the Kumbhalgarh fort extend over 38 km, and it is said to be the second longest continuous wall in the world after the Great Wall China.

Kirti Stambha is an imposing monument of victory located in the fort of Chittorgarh.

The Fort Amber is known for its Hindu-style artistic elements

City Palace was built by Udai Singh II after changing its capital to Udaipur due to the Muslim invasion

Chandramahal in the City Palace, Jaipur, built by the Kachwaha rajputs

Mehrangarh fortress in Jodhpur was built by Rao Jodha in 1459

The Jainite temple of Ranakpur]]] was built in the 15th century with the support of the Mewar rajput state.

The Chaturbhuj temple dedicated to Vishnu was the highest building in the Indian subcontinent from 1558 to 1970

Palace Laxmi Niwas, was built in the indo-sarracene style, commissioned by the Maharaja of the state of Bikaner

Buddhist architecture

Buddhist architecture developed in the Indian subcontinent, with three types of buildings associated with the religious architecture of early Buddhism: viharas (monasteries), places to venerate relics (stupas) and sanctuaries or prayer rooms (chaityas, also called chaitya grihas), which were later called temples in some places. The initial function of a stupa was the veneration and protection of the relics of Gautama Buddha. The earliest surviving example of a stupa is at Sanchi (Madhya Pradesh). In accordance with changes in religious practice, stupas were gradually incorporated into chaitya-grihas (prayer halls). This is exemplified by the Ajanta Caves and Ellora Caves (Maharashtra) complexes. The Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya in Bihar is another well-known example. The pagoda is an evolution of the Indian stupa.

The monastery of Thikse is the largest gompa of Ladakh, built in the 1500s

The monastery of Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh, built in the seventeenth century, is the largest monastery in India and the second largest in the world after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet.

The monastery of Rumtek in Sikkim was built under the direction of Changchub Dorje, 12th Karmapa Lama in the mid-1700s.

Latest Indo-Islamic architecture

Mughal architecture

The Mogol(a) architecture refers to the architectural style that developed in the Mogol empire in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries in all the ever-changing extension of its empire from medieval India. Continuing previous Iranian and local traditions, it achieved exceptional perfection by enriching them with European and other completely new elements, achieving an amalgam of Islamic, Persian, Turkish and Indian architecture.

Mogoles buildings have a uniform pattern of structure and appearance, including the use of large bulbous domes, slender minaretes in the corners, large rooms, massive vaulted doors and a delicate ornamentation. Its rulers raised many mausoleums, mosques, forts, gardens and cities, and today there were good examples in current India, Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan.

The Mogol dynasty was established in the region in 1526 after the victory of Babur in Panipat in front of the Delhi sultanate of the Lodi dynasty. During his five-year reign, Babur placed much interest in erecting new buildings, although few have survived. His grandson Akbar also built a lot and that favored the style to develop fully during his reign. Among his achievements are the tomb of Humayun (for his father), the fortress of Agra, the royal fortress-city of Fatehpur Sikri (about 40 km west of Agra) and the Buland Darwaza. The son of Akbar, Jahangir commissioned the Shalimar Gardens in Kashmir.

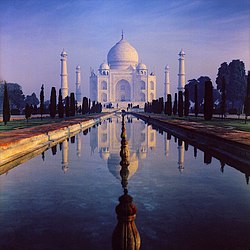

The Mogol architecture reached its cenit during the reign of Shah Jahan, who built the Jama Masjid, the strong red, the Shalimar gardens in Lahore and the most famous Mogol monument, the Taj Mahal. Although the son of Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb commissioned buildings such as the Badshahi Masjid, in Lahore, his reign corresponded with the decline of the Mogol architecture and the Empire itself.

Six elements of the Mogol architecture have been declared by the Unesco World Heritage: the strong and gardens of Shalimar in Lahore (1981), the fortress of Agra and the Taj Mahal (1983), the capital Fatehpur Sikri (1988), the tomb of Humayun (1993) and the red fort of Delhi (2007). Four others have been registered in the indicative lists—previous step to request that they be included in the World Heritage List—of two countries: Pakistan included the Badshahi Masjid de Lahore (1983), the set of the tombs of Jahangir, Asif Khan and Akbari Sarai, in Lahore (1993) and the Shah Jahan Mosque of Thatta (1993) and India included the Mogol gardens of Kashmir (2010).

| Highlighted buildings of the Mogol era | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| India | Pakistan | Bangladés | Afghanistan |

|

|

|

|

The most famous Indo-Islamic style is Mughal architecture. Its most notable examples are the series of imperial mausoleums, which began with Humayun's seminal tomb, the best known being the Taj Mahal. It is known for its features that include monumental buildings surrounded by gardens on all four sides, and delicate ornamentation works, including decorative pachin kari work and jali lattice screens.

The Red Fort in Agra (1565-1574) and the walled city of Fatehpur Sikri (1569-1574) are among the architectural achievements of this era, as is the aforementioned Taj Mahal, built as a tomb for Queen Mumtaz Mahal by Shah Jahan (1628-1658). The use of the double dome, the recessed arch, the representation of any animal or human—an essential part of Indian tradition—was prohibited in places of worship under the Islam. The Taj Mahal contains mosaics of ornamental plants. Architecture during the Mughal period, with its rulers of Turkic-Mongol origin, has shown a notable combination of Indian style combined with Islamic. The Taj Mahal in Agra, India is one of the wonders of the world.

Regional styles

In the southern regions of the Indian subcontinent, the Bahmani Sultanate and the Five Deccan Sultanates developed the Indo-Islamic architectural styles of the Deccan. The most notable examples are Charminar, Mecca Masjid, Qutb Shahi tombs, Mahmud Gawan Madrasa and Gol Gumbaz.

Within the Indian subcontinent, the Bengal region developed a distinct regional style under the independent Bengal Sultanate. It incorporated influences from Persia, Byzantium and North India, which combined with indigenous Bengali elements, such as curved roofs, corner towers and complex terracotta ornamentation. A feature of the sultanate was the relative absence of minarets. At this time many small and medium-sized medieval mosques, with multiple domes and artistic mihrabs with niches, were built throughout the region. The great mosque of Bengal was the Adina Mosque of the 20th century. XIV, the largest mosque on the Indian subcontinent. Built of stone from demolished temples, it had a monumental ribbed barrel vault over the central nave, the first giant vault of this type used on the subcontinent. The mosque was inspired by the imperial Sassanian style of Persia. The sultanate style flourished between the 14th and 16th centuries. A provincial style influenced by North India evolved in Mughal Bengal during the 17th and 18th centuries. The Mughals also copied the Bengali do-chala roof tradition for their mausoleums in northern India.

The Buland Darwaza was built by Akbar the Great to commemorate his victory over the sultanate of Gujarat

The Taj Mahal

Gol Gumbaz built by the Bijapur sultanate in decani style, the second largest pre-modern dome in the world.

Charminar (1591) in the Old Town of Hyderabad, according to legend, was built by Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah to commemorate the end of a plague that plagued the city

The Adina Mosque, the largest mosque in the Bengali Muslim architecture

Maratha architecture

The Marathas ruled much of the Indian subcontinent from the mid-17th century 17th to the early 20th century XIX. Their religious activity took full shape and soon the skies of the Maharashtrian cities were dominated by the spiers of the temples. The old ways returned with this 'renewal' of Hindu architecture, infused by the Sultanate and later by Mughal traditions. The architecture of the Maratha period was planned with courtyards adapted to tropical climates. Maratha architecture is known for its simplicity, visible logic and austere aesthetics, enriched by beautiful details, rhythm and repetition. Corridors and archways, pierced by delicate niches, doors and windows, create a space in which the articulation of open, semi-open and covered areas appears effortless and charming. The materials used during those times for construction were thin bricks, lime mortar, lime plaster, wooden columns, stone bases, basalt stone floors and brick pavements. Maharashtra is famous for its caves and rock-cut architectures. The varieties found in Maharashtra are said to be greater than the caves and rock-cut architectures of Egypt, Assyria, Persia and Greece. Buddhist monks started these caves in the 2nd century BC. C., in search of a serene and peaceful environment for meditation, and they found it in these caves on the slopes.

Sikh architecture

Sikh architecture is a style of architecture characterized by the values of progressiveness, exquisite complexity, austere beauty and logical flowing lines. Due to its progressive style, it is constantly evolving in many newly developed branches with new contemporary styles. Although Sikh architecture was initially developed within Sikhism, its style has been used in many non-religious buildings due to its beauty. 300 years ago, Sikh architecture was distinguished by its many curves and straight lines; Shri Keshgarh Sahib and the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) are the best examples.

Sikh architecture is heavily influenced by Mughal and Rajput styles of architecture. The use of onion domes, frescoes, multi-leafed arches, paired pilasters, resting work, are of Mughal origin, while the chattris, oriel windows and ornate friezes are an influence of the Rajputs.

European colonial architecture

As with the Mughals, under European colonial rule, architecture became an emblem of power, designed to support the occupying power. Numerous European countries invaded India and created architectural styles that reflect their ancestral and adopted homes. European colonizers created architecture that symbolized their mission of conquest, dedicated to the state or religion.

British colonial era (1615-1947)

The British arrived in 1615 and, over the centuries, gradually overthrew the Maratha and Sikh empires and other small independent kingdoms. The British were present in India for more than three hundred years and their legacy still remains through some buildings and infrastructure that remain in their former colonies. The main cities colonized during this period were Madras, Calcutta, Bombay, Delhi, Agra, Bankipore, Karachi, Nagpur, Bhopal and Hyderabad, which saw the emergence of Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture. Black Town described in 1855 as 'the secondary streets, occupied by the natives, are numerous, irregular and of various dimensions. Many of them are extremely narrow and poorly ventilated... a sumptuous square, the rooms opening onto a courtyard in the center." Garden houses were originally used as weekend houses for recreational use by the British High-class. However, the garden house became an ideal full-time home, abandoning the fort in the 19th century.

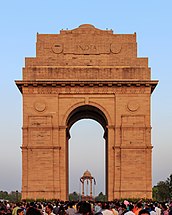

Mumbai (then known as Bombay), has some of the most notable examples of British colonial architecture, some in the neo-Gothic style (Victoria Terminus Station, Mumbai University, Rajabai Clock Tower, High Court, BMC Building), Indo-Saracenic (Prince of Wales Museum, India Gate, Taj Mahal Hotel palace) or art deco (Eros Cinema, New India Assurance Building).

Calcutta–Madras and Calcutta were similarly surrounded by water and the division of India in the north and the British in the south. An Englishwoman noted in 1750 that "the banks of the river are, as may be said, absolutely full of elegant mansions called here, as in Madras, garden houses." The esplanade row is in front of the forts with palaces lined up. Indian villages in these areas consisted of clay and thatch houses that were later transformed into brick and stone metropolises.

Indo-Saracenic architecture

Indo-Saracenic architecture evolved by combining Indian architectural features with European styles. Vincent Esch and George Wittet were pioneers in this style.

The Victoria Memorial in Calcutta is the most effective symbolism of the British Empire, built as a monument in tribute to the reign of Queen Victoria. The plan of the building consists of a large central part covered with a larger dome. Colonnades separate the two chambers. Each corner supports a smaller dome and is paved with a marble base. The monument stands on a 26-hectare garden plot surrounded by reflecting ponds.

Neoclassical architecture

Examples of neoclassical architecture in India include the British Residency (1798) and Falaknuma Palace (1893) in Hyderabad, St. Andrews Church in Madras (1821), Raj Bhawan (1803) and Metcalfe Hall (1844). in Calcutta, and the Bangalore Town Hall (1935) in Bangalore.

Art Deco

The Art Deco movement of the early 20th century 20th century quickly spread to large parts of the world. The Indian Institute of Architects, founded in Bombay in 1929, played a leading role in the propagation of the movement. The New India Assurance Building, Eros Cinema and the buildings along Marine Drive in Mumbai are prime examples.

The Victoria Terminal Station (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus) in Mumbai, designed in neogothic style by Frederick Stevens at the end of the nineteenth century

The Victoria Memorial in Kolkata was designed by William Emerson, and built between 1906 and 1921. It was inspired by the Taj Mahal.

The Gateway of India, in Bombay, is a monument erected in 1911 to commemorate the landing of King George V and Queen Mary. It was designed by George Wittet in the indo-sarracene style.

The Falaknuma Palace in Hyderabad, built between 1884 and 1893 in Palladian style, was a residence of the Hyderabad Nice.

Other colonial powers

The Portuguese had colonized parts of India, including Goa and Mumbai. The Madh Fort, the Church of St. John the Baptist (Mumbai) and the Castella de Aguada in Mumbai are remnants of Portuguese colonial rule. The Churches and Convents of Goa, a group of seven churches built by the Portuguese in Goa, are a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Republic of India (1947-present)

In recent times there has been a movement of population from rural areas to urban industrial centres, which has led to an increase in property prices in several cities in India. Urban housing in India They balance space restrictions and are intended to serve the working class. Growing awareness of ecology has influenced architecture in India during modern times. Climate-sensitive architecture has long been a feature of Indian architecture, but of late it has been losing its importance. Indian architecture reflects its diverse socio-cultural sensitivities that vary from region to region. Traditionally, it is considered to some areas belong to women. Villages in India have features such as courtyards, loggias, terraces, and balconies. Calico, chintz, and palampore—of Indian origin—highlight the assimilation of Indian textiles into global interior design. Roshandans, which are skylight-fans, are a common feature in Indian homes, especially in northern India.

Assembly Palace (1955), part of the Capitol complex in Chandigarh, designed by Le Corbusier

Deekshabhoomi Statue in Nagpur, completed in 1956, is Asia's largest stupa

The lotus temple in Delhi, completed in 1986 and one of the world's largest Bahá'ís worship houses.

20th century

At the time of independence in 1947, India had only about 300 trained architects for a population then of 330 million, and only one training institution, the Indian Institute of Architects. So the first generation of Indian architects were educated abroad.

Some of the early architects were traditionalists, such as Ganesh Deolalikar, whose design for the Supreme Court imitated Lutyens-Baker's buildings down to the last detail, and B.R. Manickam, who designed the Vidhana Soudha in Bengaluru reminiscent of Indo-Saracenic architecture.

In 1950, French architect Le Corbusier, a pioneer of the Modern Movement, was commissioned by Jawaharlal Nehru to design the city of Chandigarh. His plan included residential, commercial and industrial areas, along with parks and transportation infrastructure. At the center was the capitol, a complex of three government buildings: the Assembly Palace (1955), the High Court and the Secretariat. He also designed the Sanskar Kendra in Ahmedabad. Le Corbusier inspired the next generation of Indian architects to work in modern, rather than revivalist, styles.

Other notable examples of modern architecture in India include Louis Kahn's IIM Ahmedabad (1961), Achyut Kanvinde's IIT Kanpur (1963), B. V. Doshi's IIM Bangalore (1973), the Temple of the Lotus in Delhi, by Fariborz Sahba (1986) and Jawahar Kala Kendra (1992) and Vidhan Bhawan Bhopal (1996), by Charles Correa.

21st century

Ongoing projects in India include Amaravati City, Museum of Modern Art, Calcutta, Sardar Patel Stadium, World One, and IIT Hyderabad.

The Akshardham complex and temple in Delhi, completed in 2005 and one of the largest Hindu temples in the world

The Golden Pagoda of Namsai, completed in 2010 and one of the most important Buddhist temples in India

Temples carved into the rock

The temples carved into the rock are artificial caves - or natural, but carved, like those of Ajantā - arranged with generally flat roofs and thick columns, strangely molded, which in their general structure recall wooden assembly constructions, which must have been the primitive ones of India. Analogous to these Indian sanctuaries and of the same type of art are the monolithic constructions, temples excavated and carved in an open-air rock that are also decorated with a multitude of mythological reliefs inside and outside of them: their type is the Kailash temple, in Ellora, which measures 84 meters long by 48 meters wide and 32 meters high and which dates, according to researchers, to the 8th century.

Stupas

The stupa (a word from the Sanskrit language that means tomb or mound) is a circular building, finished in a hemispherical shape and intended to store relics of Buddha or an Indian saint. They were built of brick and stone and were usually situated on circular platforms, accessible by two ramps and surrounded by columns or a palisade. Near these buildings, chapels were built for the contemplative anaas, who must have been like the custodians of the stupa and over time these chapels were increased, decorated with statues of Buddha and joined together, reaching to form authentic convents or viharas. In these viharas of variable shapes, the unmistakable Greek influence can be seen, to the point of many of them constituting a special art that today is called Indo-Hellenic, and which is dominant in the regions of Kashmir and Gandara., and which survived until the V century of our era.

Pagodas

The modern pagoda is the development of the Indian stupa, a mound-shaped structure where sacred relics were kept. The architectural form of the stupa spread throughout Asia, taking various forms by incorporating specific details from each locality.

Due to their height, the pagodas attract lightning, which reinforced their perception as spiritually charged places. Many pagodas have a structure on their roof that works as a lightning rod, called "finial". In addition to its physical function, the finial has a symbolic meaning in Buddhism (it usually represents the mani or fifth element), and is sometimes decorated with lotus flower designs.

Gopuras

The gopuras are monumental entrances to the grounds of the pagoda or underground temple, which consist of a door crowned by a complex tower, stepped in the style of the pagoda. There are also monumental square doors and loose columns, all of them full of mythological sculptures that have as their purpose the commemoration of some important event.

Since the X century, Indian art began to merge with Arab art, constituting a new genre. But this does not mean that pagodas of an exclusively Indian type stopped being built, which with more or less alterations has remained to this day. The Arab conquest of India did not culminate until the 16th century and was generally tolerant of local worship.

Judging Indian art in architecture, it must be stated that it is not difficult to discover in it visible reminiscences of Egyptian, Assyrian and Persian art, nor is it lacking influences from Greek art, especially in Buddhist monuments. His buildings lack slenderness, are heavy and are overloaded with excessive sculptures, without offering true unity or architectural simplicity and are filled with enormous symbolism.

Image gallery

The Golden Temple in Vellore is gilded with 1500 kg of pure gold.

Dakshineswar Kali Temple is famous for its association with Ramakrishna.

Palitana temples on Shantrunjaya hill which has more than 900 temples.

Dilwara Temples are famous for their use of marble and intricate marble carvings.

Maha-Bodhi Mulagandhakuti Buddhist Temple at Sarnath.

Global Vipassana Pagoda is a Meditation Dome Hall with a capacity to seat 8,000 Vipassana meditators, largest such meditation hall in the world, near Gorai, North-west of Mumbai, India.

Gurudwara Bangla Sahib is one of the most prominent Sikh gurdwara.

Fateh Burj is dedicated to the establishment of the Sikh Misls and is the tallest minar in India.

Makkah Masjid in Hyderabad is one of the largest and oldest mosque in South India.

Rang Ghar, built by Pramatta Singha in Ahom Kingdom's capital Rongpur, is one of the earliest pavilions of outdoor stadia in the Indian subcontinent.

Further reading

- Foekema, Gerard (1996), A Complete Guide to Hoysasa TemplesAbhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-345-0.

- Gast, Klaus-Peter (2007), Modern Traditions: Contemporary Architecture in India, Birkhäuser, ISBN 978-3-7643-7754-0.

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Jaffar, S.M (1936). The Mughal Empire From Babar To Aurangzeb. Peshawar City: Muhammad Sadiq Khan. OU_1 60252.

- Keay, John, India, to History2000, HarperCollins, ISBN 0002557177

- Lach, Donald F. (1993), Asia in the Making of Europe (vol. 2)University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-46730-9.

- Livingston, Morna & Beach, Milo (2002), Steps to Water: The Ancient Stepwells of IndiaPrinceton Architectural Press, ISBN 1-56898-324-7.

- Michell, George, (1977) The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to its Meaning and Forms, 1977, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-53230-1

- Nilsson, Sten (1968). European Architecture in India 1750–1850. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-08225-4.

- Rowland, Benjamin, The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, 1967 (3rd edn.), Pelican History of Art, Penguin, ISBN 0140561021

- Savage, George (2008), interior design, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Tadgell, Christopher (1990). The history of architecture in India: from the dawn of civilization to the end of the Raj. London: Architecture Design and Technology Press. ISBN 1-854-350-4.

- Thapar, Bindia (2004). Introduction to Indian Architecture. Singapore: Periplus Editions. ISBN 0-7946-0011-5.

- Vastu-Silpa Kosha, Encyclopedia of Hindu Temple architecture and Vastu/S.K.Ramachandara Rao, Delhi, Devine Books, (Lala Murari Lal Chharia Oriental series) ISBN 978-93-81218-51-8 (Set)

- Chandra, Pramod (2008), South Asian arts, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Evenson, Norma (1989). The Indian Metropolis. New Haven and London: Yale University press. ISBN 0-300-04333-3.

- Mankekar, Kamla (2004). Temples of Goa. India: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of Ind. ISBN 978-81-2301161-5.

- Moffett, Marion; Fazio, Michael W.; Wodehouse Lawrence (2003), A World History of Architecture, McGraw-Hill Professional, ISBN 0-07-141751-6.

- Piercey, W. Douglas & Scarborough, Harold (2008), hospital, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (1996), "Mehrgarh", Oxford Companion to Archaeology edited by Brian Fagan, Oxford University Press.

- Rodda & Ubertini (2004), The Basis of Civilization-Water Science?, International Association of Hydrological Science, ISBN 1-901502-57-0.

- Sinopoli, Carla M. (2003), The Political Economy of Craft Production: Crafting Empire in South India, C. 1350-1650Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-82613-6.

- Sinopoli, Carla M. (2003), "Echoes of Empire: Vijayanagara and Historical Memory, Vijayanagara as Historical Memory", Archaeologies of memory edited by Ruth M. Van Dyke & Susan E. Alcock, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 0-631-23585-X.

- Singh, Vijay P. & Yadava, R. N. (2003), Water Resources System Operation: Proceedings of the International Conference on Water and Environment, Allied Publishers, ISBN 81-7764-548-X.

- Teresi, Dick (2002), Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science—from the Babylonians to the Maya, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-684-83718-8.

See also

- Jaina temple

Contenido relacionado

29

Run (print)

Congregation

![Estupa nº.2 de Sanchi, la stupa más antigua conocida con importantes exhibiciones de relieves decorativos, c. 125 a.C.[48]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/91/Sanchi_Stupa_number_2_KSP_3660.jpg/270px-Sanchi_Stupa_number_2_KSP_3660.jpg)

![Puerta este y barandas de la estupa de Bharhut. Barandillas esculpidas: 115 a.C., toranas: 75 a.C.[44]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/91/East_Gateway_and_Railings_Bharhut_Stupa.jpg/298px-East_Gateway_and_Railings_Bharhut_Stupa.jpg)

![La Gran Estupa en Sanchi.[49] Toranas decoradas construidas desde el siglo I a.C. hasta el siglo I d. C.[44]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/Sanchi1_N-MP-220.jpg/269px-Sanchi1_N-MP-220.jpg)

![Relieve de un templo de varias plantas, siglo II, estupa de Ghantasala[54][55]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/75/Andhra_pradesh%2C_santuario_a_pi%C3%B9_piani%2C_da_ghantasala%2C_90-110_ca..JPG/186px-Andhra_pradesh%2C_santuario_a_pi%C3%B9_piani%2C_da_ghantasala%2C_90-110_ca..JPG)

![Ilustración del templo n.º 40 en Sanchi, fechada en el siglo III a. C.[56]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/40/IA_Temple_40_Sanchi.jpg/218px-IA_Temple_40_Sanchi.jpg)

![El templo tallado en la roca del Shore Temple de los templos en Mahabalipuram, 700-728[77]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/40/Shore_temple%2C_mahabalipuram.jpg/120px-Shore_temple%2C_mahabalipuram.jpg)

![Las ruinas de la Nalanda Mahavihara en Nalanda.[78]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Nalanda_University_India_ruins.jpg/240px-Nalanda_University_India_ruins.jpg)

![Teli ka Mandir, un templo hindú del siglo VIII/IX construido por el emperador pratihara Mihira Bhoja[79]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/Teli_ka_mandir_fort_Gwalior_-_panoramio_-_Gyanendrasinghchauha%E2%80%A6_%281%29.jpg/119px-Teli_ka_mandir_fort_Gwalior_-_panoramio_-_Gyanendrasinghchauha%E2%80%A6_%281%29.jpg)

![El templo de Galaganatha en el complejo de Pattadakal es un ejemplo de la arquitectura de los chalukya de Badami[77]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7d/Galaganatha_Temple%2C_Pattadakal%2C_Karnataka.jpg/161px-Galaganatha_Temple%2C_Pattadakal%2C_Karnataka.jpg)

![La gopuram (torre) de granito del templo Brihadeeswarar en Thanjavur, que fue completada en 1010 por el Raja Raja Chola I.[80]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5f/Big_Temple-Temple.jpg/135px-Big_Temple-Temple.jpg)

![Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (puerta Warangal) en ruinas, construida por la dinastía Kakatiya[81]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/Warangal_fort.jpg/112px-Warangal_fort.jpg)

![El fuerte Amber es conocido por sus elementos artísticos de estilo hindú[93]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1b/Amber_Fort_%28%E0%A4%86%E0%A4%AE%E0%A5%87%E0%A4%B0_%E0%A4%95%E0%A4%BE_%E0%A4%95%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%B2%E0%A4%BE_%29.jpg/270px-Amber_Fort_%28%E0%A4%86%E0%A4%AE%E0%A5%87%E0%A4%B0_%E0%A4%95%E0%A4%BE_%E0%A4%95%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%B2%E0%A4%BE_%29.jpg)

![El templo jainita de Ranakpur]] se construyó en el siglo XV con el apoyo del estado rajput de Mewar.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0f/Jain_Temple_Ranakpur.jpg/371px-Jain_Temple_Ranakpur.jpg)

![El monasterio de Rumtek en Sikkim was built under the direction of Changchub Dorje, 12th Karmapa Lama in the mid-1700s.[94]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e5/Vikramjit-Kakati-Rumtek.jpg/382px-Vikramjit-Kakati-Rumtek.jpg)

![Gol Gumbaz construido por el sultanato de Bijapur en estilo decani, la segunda cúpula pre-moderna más grande del mundo.[note 1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9f/Gol_Gumbaz%2C_Bijapur%2C_Karnataka%2C_India.JPG/240px-Gol_Gumbaz%2C_Bijapur%2C_Karnataka%2C_India.JPG)

![La Estación terminal Victoria (ahora Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus) en Mumbai, diseñada en estilo neogótico por Frederick Stevens a finales del siglo XIX[123]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c5/Chhatrapati_Shivaji_Terminus_%28Victoria_Terminus%29.jpg/309px-Chhatrapati_Shivaji_Terminus_%28Victoria_Terminus%29.jpg)

![Palacio de la Asamblea (1955), parte del complejo del Capitolio en Chandigarh, diseñado por Le Corbusier[133]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1a/Palace_of_Assembly_Chandigarh_2006.jpg/431px-Palace_of_Assembly_Chandigarh_2006.jpg)

![Estupa Deekshabhoomi en Nagpur, completada en 1956, es la estupa más grande de Asia[134]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/38/Deekshabhoomi_-_panoramio.jpg/241px-Deekshabhoomi_-_panoramio.jpg)

![El templo del loto en Delhi, completado en 1986 y una de las casas de adoración bahá'ís más grandes del mundo.[135][136]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fc/LotusDelhi.jpg/292px-LotusDelhi.jpg)

![Palitana temples on Shantrunjaya hill which has more than 900 temples.[138]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Palitana.jpg/145px-Palitana.jpg)