Inca empire

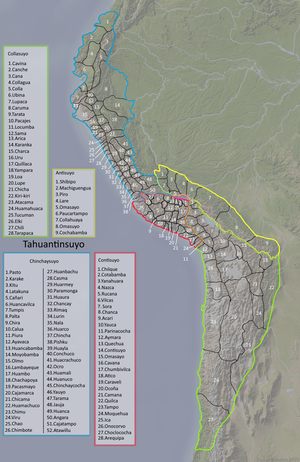

The Inca Empire, Inca Empire or Tahuantinsuyo (Spanishization of the place name in Quechua: Tawantinsuyu, lit. 'the four regions or divisions') was the most extensive and developed empire in pre-Columbian America. The period of his domain is known as Incanato or Incario. It arose in the region of the Peruvian Andes between the 15th and 16th centuries as a consequence of the expansion of the curacazgo of Cuzco, being the second historical stage and the period of greatest apogee of the Inca civilization. Covered 2,500,000 km² between the Pacific Ocean in the west and the Amazon rainforest in the east, from the Ancasmayo River (Colombia) in the north to the Maule River (Chile).

The origins of the empire go back to the victory of the multi-ethnic groups, led by Pachacútec, against the Chanca confederation in Yawarpampa, in the middle of the century XV, around 1438. After the victory, the Inca chieftaincy was reorganized by Pachacútec, with whom the Inca Empire began a stage of continuous expansion, which continued with his son, the tenth Inca Amaru Inca Yupanqui, later by from the eleventh Inca Túpac Yupanqui, and finally from the twelfth Inca Huayna Cápac, who consolidated the territories. In this stage, the Inca civilization achieved the maximum expansion of its culture, technology and science, developing its own knowledge and that of the Andean region, as well as assimilating that of other conquered states.

After this period of heyday, the empire went into decline due to various problems, the main one being the confrontation for the throne between the sons of Huayna Cápac: the brothers Huáscar and Atahualpa, which even led to a civil war. Among the Incas, smallpox killed the monarch Huayna Cápac, provoked the civil war prior to the Spanish appearance and caused a demographic disaster in Tahuantinsuyo. Finally Atahualpa would win in 1532. However, his rise to power coincided with the arrival of the Spanish troops under the command of Francisco Pizarro, who captured the Inca and later executed him. With the capture of Cuzco in 1533, the Inca Empire ended. However, several rebel Incas, known as the "Incas of Vilcabamba", rebelled against the Spanish until 1572, when the last of them was captured and beheaded: Túpac Amaru I.

The Incas considered their king, the Sapa Inca, as the "son of the sun." Many local forms of worship persisted in the empire, most of them related to local sacred Huacas, but Inca leaders encouraged the sun cult of Inti - their sun god - and imposed their sovereignty over other cults such as that of Pachamama.

The Inca economy has been described in contradictory ways by scholars: as "feudal, slave-owning, socialist." The Inca empire functioned largely without money and without markets. Instead, the exchange of goods and services was based on reciprocity between individuals, groups, and Inca rulers. 'Taxes' it consisted of a labor obligation of a person for the Empire. Inca rulers (who theoretically owned all the means of production) reciprocated by granting access to land and property and by providing food and drink at their subjects' celebrations.

History

Historical sources

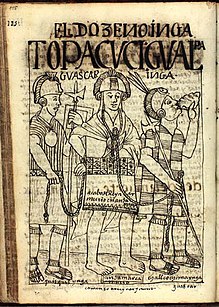

European chronicles of the Inca empire

The first written traces of the Inca empire are the chronicles recorded by various European authors (later there were mestizo and indigenous chroniclers who also compiled the history of the Incas); these authors compiled the "Inca history" based on accounts collected throughout the empire. The first chroniclers had to face several difficulties in being able to translate the Inca history since, in addition to existing a language barrier, they faced the problem of interpreting a way to see the world totally different from what they were used to. This led to the existence of several contradictions between colonial texts and an example of this is represented by the chronologies of the Inca rulers; thus, in many chronicles the same feats, facts and episodes are attributed to different rulers.

Regarding the chronicles of the Inca empire, it is important to note that their various authors had certain interests when writing them. In the case of the Spanish chroniclers, their interest was "to legitimize the conquest through history", for this reason, in many chronicles it is pointed out that the Incas conquered using violence entirely and therefore had no rights over the conquered territories. In another case, chroniclers linked to the Catholic Church sought to legitimize evangelization by describing the Inca religion as the work of the devil, the Incas as sons of Noah, and trying to identify the Inca deities with biblical beliefs or European folklore. there were other mestizo and indigenous chroniclers who also had an interest in extolling the empire or one of the panacas with which they were related, such as the case of the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, in his work "Comentario reales de los Incas" who showed an idealized Inca empire where poverty did not exist, wealth was distributed and resources were exploited rationally.

Inca historical sources

The ayllus and panacas had special songs through which they narrated their history. These songs were performed in certain ceremonies in front of the Inca. These stories, by way of collective memory, constitute the first historical records collected in the chronicles.

Another resource used to record history were some cloaks and tables that contained paintings representing heroic passages. These documents were kept in a place called Poquen Cancha. It is known that Viceroy Francisco de Toledo sent King Felipe II four cloths illustrating the life of the Incas, adding in his own words that "the yndian painters did not have the curiosity of those from there."

In addition, some past events were stored in the quipus, although it is not known how these systems of cords and knots could be used to store historical facts, there are several chronicles that describe that the quipus were used to evoke the deeds of the rulers.

In general, in the Inca empire they remembered the facts that seemed important to them to remember and precision was not necessary. In addition, the rulers could intentionally exclude from the historical records some facts that might upset them. María Rostworowski calls this quality of Inca history a "political amnesia" that was assumed by the common people but was remembered by the affected panacas or ayllus, a factor that contributed to future contradictions in European chronicles about the Incas.

The reinvention of traditions

After the meeting of Hispanic and Andean culture, writing was established as a means of transmission and recording of information; In addition, a process of miscegenation and syncretism began that gave rise to the recreation of traditions and the invention of others.

The contribution for this recreation and invention of traditions was both Hispanic and Andean; This is evidenced in the chronicles of the XVI century where characters such as the case of Tunupa and Huiracocha with the apostles Tomás and Bartholomew, describing them as white, bearded men who taught. Likewise, the European imaginary sought, and even believed to find, "el dorado" and the "country of the Amazons" in the new world. In other cases, they claimed that Cuzco had the profile of an American lion (puma), drawing similarities to some European Renaissance cities that had a lion profile. More recently, in the XX, other elements of this reinvention of traditions appear, such as the cases of the flag of the Inca empire and the Cuzco ceremony of Inti Raymi. It should be noted that all these reinventions, They are part of a natural process in all cultures, but to understand Inca history it is necessary to differentiate which are syncretic or invented aspects and which are not.

Background to the founding of the Inca Empire

Around 900 AD. C. begins the decline of the Huari and Tiahuanaco states in the central Andean area. In the case of Huari, the city of Wari begins to lose political power in opposition to some of its peripheral cities, as evidenced by the case of Pachacámac located in front of the sea. While in the case of Tiahuanaco, the process of decline it began in its colonies on the coast in a bloody way, as evidenced by the case of Azapa; in Collao, on the other hand, Tiahuanaco gradually lost its power and while it lost hegemony its population emigrated and founded new towns.

As a hypothesis about the decline of Huari and Tiahuanaco, there is evidence of a prolonged period of drought that lasted from the year 900 AD. C. until 1200 AD. C. in the central Andes. Archaeologically, there is evidence of long population migration processes throughout the Andes during the post-huari and post-tiahuanaco periods. Archeology reveals that in the inter-Andean valleys, the population built their settlements on top of hills seeking security, which tells us of a prolonged period of ethnic confrontations. On the coast, meanwhile, various groups achieved political stability, as evidenced by the cases of the Chimú, Chimú and the Ychsma.

This historical period was embodied in Andean legends and myths in different ways. In the oral traditions of the Andes, reference is made to the fact that in the beginning the peoples made long walks in search of fertile lands, mythical heroes emerged who were, generally, semi-divine and who were guided by supernatural beings (the sun, the moon, etc.). These mythical heroes usually had some power. In this way the figures of Manco Cápac arise, in the founding case of Cuzco; or Pariacaca in the case of Huarochirí.

Mythical origins

There are two widespread myths about the origin of the Cuzco ethnic group. The most widespread is the Garcilasian version of the couple Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo; the other is the myth of the four Ayar brothers and their four sisters, this last myth is collected by Betanzos, Waldemar Espinoza, Cieza de León, Guamán Poma de Ayala, Santa Cruz Pachacuti and Sarmiento de Gamboa.

The legend of Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo

Legend compiled by the Inca chronicler Garcilaso de la Vega in his work "Los comentarios reales de los Incas". This narrates the adventure of a couple, Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo, who, sent by the Sun god, left the depths of Lake Titicaca (pacarina: place of sacred origin) and marched north. They carried a golden rod, given by the Sun god; the message was clear: in the place where the golden rod sank, there they would found a city, there they would settle. Precisely the rod sank in the Guanacaure hill, in the Acamama valley; therefore, the couple decided to stay there and informed the inhabitants of those areas that they were sent by the god Inti; and then they proceeded to teach them the cultivation of the land and weaving. In this way the Inca civilization would begin.

The other explanation, not legendary, but historical, and therefore more in line with reality, was proposed by Waldemar Espinoza, who argued as follows: "at the end of the aforementioned century (siglo XII), the Puquina-speaking state, more commonly called Tiahuanaco, was assaulted and invaded by huge waves of humans coming from the south (from Tucumán, Coquimbo) so suddenly and impetuously that they did not leave him time to mount resistance. Such invaders, by all accounts, were none other than the Aymaras." This version makes it clear that the founders of the Inca society came from the south and fled from the Aymara onslaught.

Almost all of the elite Hanan taipicalas were annihilated and the hurin taipicalas, a priestly elite, managed to flee and take refuge on the islands of Lake Titicaca. Then from there the native settlers such as the huallas, alcahuisas, sahuaseras, antasayac, lare, poque, pinaguas and ayamarcas who opposed their establishment advanced to the valley; To overcome this conflict, the Puquina elite carried out multiple strategies, one of which was the marriage alliance, to later become a confederation of states and finally, a great Andean empire.

The legend of the Ayar Brothers

It was compiled by various chroniclers, including Juan de Betanzos, Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala, Pedro Cieza de León, Juan Santacruz Pachacuti and Pedro Sarmiento. According to this myth, the story began in three caves located on the Tamputoco hill called Maras Toco, Sútic Toco and Cápac Toco; from which came three groups called Maras, Tampus and Ayar. The Ayar brothers were four men and four women, the men were Ayar Uchu, Ayar Manco, Ayar Cachi and Ayar Auca. Uchu corresponds to chili, Manco to a cereal (Bromus Mango) and Cachi to salt; the onomastics to these three names gives us to understand a cult for the products of the earth. Auca, on the other hand, referred to the warrior attitude.

These 4 siblings were accompanied by their sisters Mama Ocllo, Mama Raua, Mama Ipacura or Mama Cura, and finally Mama Huaco.

The 8 brothers went with their ayllus looking for a place to settle traveling from south to north, on their way they did agricultural work and when they harvested they withdrew looking for another place. First they made their way through Guaynacancha, there Mama Ocllo got pregnant by Ayar Manco. Then they advanced to Tamboquiro, where Sinchi Roca was born. Later they arrived at Pallata and from there to Haysquisrro, these trips lasted several years.

In Haysquisrro they conspired against Ayar Cachi; Fearful of the power he held, since he could knock down hills and form ravines with the shot of his slingshot, they asked him to return to Tambotoco to collect the topacusi (golden vessels), the napa (insignia) and some seeds, once inside an envoy named Tambochacay locked him inside the cave.

Then they continued their trip to Quirirmanta, where they officiated a council deciding that Ayar Manco would be the boss but first he should marry Mama Ocllo; while Ayar Uchu would have to petrify himself and transform into a huaca that would be called Huanacauri, with this act Ayar Uchu would become a sacred being.

The trip continued to Matagua performing the huarachicuy for the first time, after that they pierced the ears of Sinchi Roca. After this, Mama Huaco tried her luck and threw two golden rods, one fell in Colcabamba but failed to penetrate the ground; the other fell in Guaynapata sinking gently. Regarding this event, other authors attribute the launching of the golden rod to Ayar Manco, but all agree that it was in Guaynapata where the founding staff sank.

After that there were several attempts to reach the place where the rod sank, as they were repelled by the natives, until Ayar Manco made the decision to send Ayar Auca to go ahead with his aillu and populate that land. Arriving at that place, Ayar Auca turned to stone, in the place that would later be the Coricancha. After several confrontations with the local population, Ayar Manco and Ayar Uchu arrived at the place and took possession of it. From that moment on, Ayar Manco was renamed Manco Cápac.

Research on the founding myths of Cuzco

Regarding the two founding myths, the legend of the founding couple (Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo), arises after the enthronement of Pachacútec, since it relates a pan-Andean huaca, such as Lake Titicaca, with the foundation of Cuzco. Garcilaso translated the myth by posing a couple who came to civilize barbarian peoples by teaching them new technologies; The real fact is that it is currently known that the central Andean area already had ancient technological advances that were disseminated by the Pan-Andean states of Huari and Tiahuanaco, and that they were already known to the small towns that inhabited the Cuzco area.

Although both myths narrate a population exodus looking for fertile lands, only the myth of the Ayar brothers narrates the petrification of characters and this last story is very recurrent in other ethnic groups of the central Andean area.

Regarding the location of the caves, Bingham in 1912 commissioned George Eaton to locate the Tambotoco windows, taking into account that the town of Pacarictambo still exists but Eaton's search did not find the caves. Then in 1945, Jorge Muelle, Luis Llanos and César Lobón traveled through Mollebamba looking for the site of Guaynacancha (in the Pacarictambo district), there they associated a group of caves near the Puma Orqo rock with the Tambotoco caves. Later Gary Urton contributed research on the town of Pacarictambo, stating that it was moved in colonial times and that it was very possible that its original location would have been close to the ruins of Maukallajta, close to the site found by Muelle, Llanos and Lobón in 1945..

In general, the story of the Ayar brothers shows us a warrior man (Ayar Auca) and a warrior woman (Mama Huaco), giving a different vision to that of Garcilaso, where the female role is dedicated to weaving, cooking and childcare; This myth narrates an event that occurred during one of the many battles to take possession of Cuzco, in which Mama Huaco wounds a man, then opens his chest and blows her "bofes", causing the people of Acamama to flee in fear.

Origin (historical)

Government of Manco Cápac

He founded the Inca empire, approximately the year 1200 AD. C. and was its first ruler. He was characterized by the domain of the pre-Inca tribes that lived dispersed in Cuzco and its surroundings. Manco Cápac unified the huallas, poques and lares, and with them he settled in the lower part of the city. Thus began the dynasty of the Urin Cuzco. A short time later he ordered the construction of the first residence of the Incas, the Inticancha or Temple of the Sun . His sister and wife was Mama Ocllo.

- Legendary Empire (Local phase):

Pre-state era: formation

Little mobility; There is little news of his successive governments: Sinchi Roca , who would have governed from 1230 to 1260 without achieving significant expansion in the then kingdom of Cuzco; Lloque Yupanqui , which would culminate his government in 1290 with the merit of reaching various alliances with different towns surrounding the Incas; Mayta Cápac recognized for his victory over the acllahuiza and that would culminate his government around 1320; and Cápac Yupanqui, the first conqueror, to whom we owe the victory against the condesuyo. In a coup, Cápac Yupanqui would overthrow Tarco Huamán, successor to Mayta Cápac. This period would have lasted for approximately 120 years, beginning around AD 1230. C. (year in which the government of Sinchi Roca begins), until 1350 d. C. (year in which the government of Cápac Yupanqui culminates after his poisoning by Cusi Chombo in a coup organized by Inca Roca. Who would be his successor, Quispe Yupanqui, would also be assassinated).

A more general ethnohistoric view of this period describes that the Incas arrived in Cuzco around the [[13th century]] d. C. and, in the following century, they managed to impose themselves on the populations closest to the Cuzco valley. Since their arrival in Cuzco, the Incas would have mixed with some of the peoples that inhabited the place and expelled others. They would have organized their predominance by making alliances with different curacas establishing kinship relationships and by fighting wars. To these practices, which continued, were added others such as the collection of surpluses and labor and the practice of redistribution. To understand this situation, it would also be necessary to consider that the religious prestige that accompanied the Incas was the cornerstone of the effectiveness of all the expansion mechanisms that they used at this time.

This stage is called pre-state, because at no time did a solid idea of an Inca state or nation emerge; but the Andean idea of being considered a macro-ethnic group still existed, although this would change when the territory of the ethnic group expanded significantly after the government of Cápac Yupanqui and his various conquests. The end of this period coincides with the end of the dynasty of the rulers Urin Cuzco ( Rurin Qusqu ), who saw in Cápac Yupanqui the last representative of him.

State Time: Great Expansion

With Pachacútec the imperial model began, with Túpac Inca Yupanqui it expanded and with Huayna Cápac it was consolidated.

Government of Pachacútec

During his government, territorial expansion began, thus inaugurating the imperial period by annexing numerous towns. Pachacútec improved the organization of the state, dividing the empire into four regions or suyus. To the north, he subdued the Huancas and Tarmas , until he reached the area of the Cajamarcas and Cañaris (Ecuador). To the south he subdued the collas and lupacas , who occupied the highland plateau. He organized the chasquis and instituted the obligation of tributes.

- Historical Empire (Explosion phase):

- - Dynasty Hanan Cuzco: 1438-1471.

Government of Tupac Yupanqui

He was a prominent soldier who achieved important victories during the government of his father Pachacútec. In 1471 he assumed the throne and expanded the borders of the empire to the south, reaching the Maule River in Chile. He also subdued the Chimú kingdom and some towns in the highlands and northern Argentina. He put down the resistance of the chachapoyas and advanced north to Quito. He wanted to venture into the jungle, but a rebellion by the collas forced him to deviate towards Collao. He improved the collection of tributes and appointed new visiting rulers (tuqriq) . He died in 1493.

- Historical Empire (Explosion phase):

- - Dynasty Hanan Cuzco: 1471-1493.

Government of Huayna Cápac

He is considered the last sovereign of the Inca. During his government, he continued the policy of his father, Túpac Inca Yupanqui , regarding the organization and strengthening of the state. In order to preserve the conquered territories, he had to put down continuous uprisings in a bloody way. He defeated the chachapoyas and annexed the region of the gulf of Guayaquil, reaching the Ancasmayo river (Colombia). While in Quito, he became seriously ill and died in 1525. Some Spanish chronicles postulate that he also expanded the borders of the empire further south, and that he would have even reached the Biobío River in Chile; although this southernmost limit has not been verified archaeologically, and it is not historically accepted. With his death the decline of the empire began.

- Historical Empire (Explosion phase):

- - Dynasty Hanan Cuzco: 1493-1525.

Succession crisis

Succession crises were a conjunctural phenomenon that was very frequent in the political history of the empire. The one who aspired to be the new sovereign had to demonstrate that he was the "most skilful", he had to be confirmed by an oracle and also had to win followers in the panacas of Cuzco.

Huayna Cápac named Ninan Cuyuchi (son of Coya Mama-Cussi-Rimay[citation needed]) as his heir, but the priest of the sun made a sacrifice in the one who saw that luck would not favor Ninan Cuyuchi. For this reason, when Huayna Cápac died in Quito, he was carried on a litter to Cuzco, keeping his death a secret, to maintain political order. In this context, Raura Ocllo, Huáscar's mother who was in Quito with Huayna Cápac, traveled quickly to Cuzco accompanied by a few dried apricots to prepare for Huáscar's enthronement. According to María Rostworowski, it was Raura Ocllo who convinced the Cuzco panacas to name Huáscar as his successor; while Atahualpa stayed in Quito along with other nobles.

For his part, Atahualpa was the son of Tocto Coca (a woman who belonged to the panaca of "Hatun Ayllu"); and when his father died, he ordered the construction of a palace in his honor in the town of Tomebamba. This fact angered the curaca of Tomebamba named Ullco Colla, who sent messages to Huáscar accusing Atahualpa of revolt; In addition, Atahualpa stayed in the north accompanied by several important generals loyal to Huayna Cápac, who had a special appreciation for Atahualpa. After this fact, Atahualpa sent presents to his brother Huáscar, but the latter ordered to make drums with the leathers of the messengers. According to Rostworowski, Atahualpa was incited to rebel by his father's generals, with whom he had participated in several battles against the natives to the north.

In this context, the rebellion of the “cañaris” occurred, who took Atahualpa prisoner, locking him in a tambo. Atahualpa's escape takes on a mythical context, because according to the speakers Atahualpa was turned into amaru (snake) by his father's sun, and thus managed to escape from confinement. Other chronicles state that it was a woman who gave him a copper bar with which he made a forado and was able to escape from confinement. Once free, Atahualpa gathered an army and assassinated his enemies in Quito and Tomebamba, the latter city was razed in revenge for Ullco Colla; he then advanced to Tumbes trying to advance to Puná Island, but the curaca of Puná went ahead and razed Tumbes. With the town of Tumbes devastated, the first Spaniards set foot on Inca territory.

Meanwhile, Huáscar tried to stabilize his enthronement in Cuzco with the support of the panacas. Regarding Huáscar, the chroniclers describe several political errors that diminished the support of Cuzco. Firstly, he did not attend the royal ayllus as was the custom, he did not attend the public lunches in the Cuzco plaza (which strengthened ties of reciprocity and kinship). He eliminated the ayllus custodians from his personal guard and appointed "Cañari" and "Chachapoya" warriors as his royal guard. Huáscar doubted the loyalty of the Cuzco panacas and surrounded himself with other nobles. Fearing a rebellion by the Cuzco nobility, he threatened to bury the royal mummies and take their lands from the panacas. Little by little Huáscar was gaining enemies in a period of intrigues among the Cuzco nobility, in his counterpart Atahualpa was gaining followers.

Government of Huáscar

Huáscar did not agree with Huayna Cápac's will, since he believed he had the right to inherit the entire Inca empire according to Inca laws, customs and traditions. Huáscar faced in 1531 after many years of peace his half-brother Atahualpa, who also considered himself the legitimate heir to the throne in the Quito region. Very soon, important regions of the empire were shaken by bloody battles between troops from Cuzco and Quito, which ended with the final victory of the latter. Huáscar was taken prisoner and later killed by order of Atahualpa.

- Historical Empire (Explosion phase):

- - Dynasty Hanan Cuzco: 1525 - 1532.

Government of Atahualpa

Son of Huayna Cápac with the Inca noblewoman Tocto Ocllo Coca. After the death of his father, he became governor of the city of Quito. Either due to the fear Huáscar had of his brother or the ambition to become sovereign, he later proclaimed himself an Inca in Quito and thus began the war of Inca succession. His troops, led by Chalcuchímac and Quizquiz , defeated Huáscar's army in the battle of Quipaipán (Apurímac) and triumphantly entered Cuzco. Aware of the victory, Atahualpa marched to Cajamarca to be crowned Inca. On the way he was acclaimed by the peoples of the north. However, upon reaching Cajamarca, he was taken prisoner by the Spanish conquistadors in the Cajamarca ambush. It was the year 1532. This fact marked the end of the Inca empire.

Contrary to what is thought, Atahualpa (who ruled de facto between 1532 and 1533), is not part of the capaccuna by never gird the mascaipacha. Therefore it is improper to call it Sapa Inca, as it is sometimes called. Quito was completely burnt down by General Rumiñahui in 1534, before the arrival of the Spanish in the city in search of the treasures of the empire, and founded again by the Spanish Sebastián de Belalcázar on the ashes of the Inca town on December 6, 1534.

The Fall

At the time of the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores, the Andes were in a decisive phase of the Inca civil war. The atahualpistas had overwhelmed the Cuzco forces until they captured the capital itself. During their advance, they had committed numerous atrocities against the ethnic groups and cities that had supported Huáscar's Cuzco; It is worth remembering what was perpetrated against the Cañaris in Tomebamba and that the Atahualpista general Chalcuchímac was about to repeat in Hatun Xauxa against the Huancas. This context of superiority generated a climate of pedantry and arrogance in the Atahualpista armies, particularly in Atahualpa himself.

This arrogance would be decisive in allowing the Spanish to surprise and capture Atahualpa in Cajamarca: a turning point in leaving the Atahualpistas politically, ideologically, and militarily headless, at least temporarily. It would also deal a severe blow to their military situation, since Quizquiz and Chalcuchímac (the main remaining Atahualpista generals) were unable to attack the Spanish due to fear that they would execute their captive leader. Using Atahualpa as a hostage, the Spanish would gain invaluable time and resources on their journey to Cusco.

Many of those who had suffered the Atahualpista reprisals ended up allying with the Hispanic forces; highlighting ethnic groups such as the Huancas, Cañaris and the Cuzqueños themselves, whose remnants were revitalized thanks to the turnaround in the military situation. The Spanish, in order to curry favor with the Andes, named a series of new Incas according to the official procedures of Cuzco. All these factors combined explain how the Spanish managed to peacefully take huge portions of territory with hardly any armed conflicts. They even used propaganda narratives to their advantage to delegitimize opposing forces that truly posed a threat, such as the Atahualpista remnants (who resisted until 1535) and the Vilcabamba rebels (who resisted until 1572).

Nevertheless, a considerable portion of towns, cities, and ethnic groups remained neutral, manifesting a disregard for the forces that crossed their territories since they were fed up with the continuous years of war, which prevented them from attending to vital agricultural activities..

Colonial Incas

Since the arrival of the Spanish, on their march to Cuzco.

- Tupac Hualpa (1533) two months, September and October. Inca crowned by the Spaniards, dies before arriving at the Imperial City in the Mantaro Valley.

- Manco Inca (1533-1545), Inca crowned by the Spaniards (1533) rebelled against them (1536) leaves the Cuzco, moving its capital first to Ollantaytambo and then to Vilcabamba.

- Paullu Inca (1537-1549), Inca crowned by the Spaniards during the government of Manco Inca (1537), who also reigned four years after his death, during the government of Sayri Túpac.

Neo-Inca State: Incas of Vilcabamba

They were rulers of peoples descendants of the Incas, it was officially the last Inca dynasty, founded after the rebellion of Manco Inca and as the last resistance to the Spanish conquerors.

- Manco Inca until his death in 1545 Inca de Vilcabamba.

- Sayri Túpac (1545-1558) Inca de Vilcabamba.

- Titu Cusi Yupanqui (1558-1571) Inca de Vilcabamba.

- Tupac Amaru I (1571-1572) Inca de Vilcabamba.

Geography and territory

Geographic location

It was the Andean region, due to the presence of the Andes mountain range, it is characterized by the diversity of its ecology: desert coasts, tropical landscapes, dry and cold highlands that at first glance seem one of the least favorable environments for the life of man. However, the men who inhabited it have shown over many centuries to be capable not only of surviving in such circumstances, but also of dominating the geographical environment and creating a series of flourishing civilizations. The most famous of these was the Inca empire, which occupied a vast territory of South America, which includes the current or parts of the territories of the Republics of Peru, Ecuador, western Bolivia, northern Chile, extreme south-western Colombia and northwestern Argentina.

Distribution of the Inca empire within the current countries of South America

The Incas in Argentina

According to historical sources in the territory of Argentina, between 1479 and 1535, the Inca empire conquered the western parts of the current provinces of Catamarca, Tucumán, Salta, Jujuy, La Rioja, San Juan, and the extreme northwest of Mendoza incorporating them into Collasuyo. Some investigations suggest the Inca influence in part of the Province of Santiago del Estero (interfluvial area where the city of Santiago del Estero is located), but the incorporation of that area into the empire has not been proven. Traditionally the conquest is attributed to the Inca Túpac Yupanqui. The peoples that then inhabited that region, the Omaguacas, the Diaguitas (including the Calchaquíes), the Huarpes and others, tried to resist but the Incas managed to dominate them, transferring to their territories the mitimaes or deported settlers from the Chichas tribes, who They lived in what is the southwest of current Bolivian territory.

The Incas built roads (the Camino del Inca), agricultural and textile production centers, settlements (collcas and tambos), fortresses (pucarás) and numerous sanctuaries at the top of the mountains where they performed human sacrifices, especially young girls. and of children as shown by the mummies of Llullaillaco, also using pre-existing constructions.

Among the most important Inca establishments in Argentina are the Potrero de Payogasta in Salta, the Tambería del Inca in La Rioja, the pucará de Aconquija and the Shincal in London, both in Catamarca, the pucará de Tilcara in Jujuy and the ruins of Quilmes in Tucumán, most of which were pre-Inca and were organized into an urban network within their empire, establishing military checkpoints there.

The Inca provinces (wamanis) in the current Argentine territory were five:

- Humahuaca', with probable header in Tilcara, arriving north to Talina, currently in the South of Bolivia. Inhabited by mitimáes chichas.

- Chicoana or Sikuani, inhabited by the roars, it spread through the Atacama puna floor and the northern part of the Calchaquíes valleys to near Seclantás and probably covered from the Salinas Grandes de Jujuy to the south of La Paya in Salta, where the former Chicoana was its capital.

- Quire-Quire or Kiri-Kiri, which included the rest of the valleys Calchaquíes beginning in Pompona (now La Angostura), the entire valley of Santa Maria and the valleys of Andalgalá, Hualfín and Abaucán. Inhabited calchaquíes and yocaviles and by a large number of mitimáes, it had two main seats in Shincal and Tolombón.

- Tucumán or TucmuaHe understood the eastern valleys and the smuggled mountains.

- The southernmost province probably spread from La Rioja to the mountains of the Cordón de Plata, reaching the hill Tupungato in Mendoza and perhaps was part of, with the name Cuyo or Kuyun of the province of Chile or Chili.

The Incas in Bolivia

In the territory of Bolivia, after around 1100 B.C. C. Tiwanaku disappeared, there was a fight between the different groups that inhabited the region: aimaras, collas, lupacas and pacajes. The aimaras establish a domain that encompasses Arequipa and Puno in Peru, La Paz and Oruro, which lasted until, in 1438, the Inca Pachacútec defeated the last Colla sovereign, Chunqui Cápac, incorporating the Bolivian highlands into the Inca empire, as part of the province of Collasuyo, and imposing Quechua as the official language, although Aymara continued to be spoken regularly. In addition, the Inca empire adopted Tiwanakota architectural styles and other knowledge. Later, the Inca Huayna Cápac ordered the construction of fortresses on the eastern border to stop the advance of the Chiriguanos.

According to a legend, the founders of the Inca empire, Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo, were born from the foam of Lake Titicaca, between Peru and Bolivia.

The Incas in Brazil

In the territory of Brazil, there are two roads that the Incas would have built, in the northeast from Quito reaching the current state of Roraima on the border of the Guianas, which according to the Chilean researcher Roland Stevenson arises from a mispronunciation of the name Quechua "Guayna Capac", father of Huáscar and Atahualpa, and the so-called Peabiru road (pea-road; Biru-Perú) that connects the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean, in the current state of São Paulo, with the city of Cuzco in the Andes through which the Portuguese Aleixo García would have raided taking precious metals from present-day Bolivia, before the Spanish conquest.[citation required]

The Incas in Chile

In the territory of Chile, during the reign of Túpac Yupanqui, the conquest of the Diaguitas and Aconcaguas took place in the transversal valleys of the Norte Chico of Chile and the Central Zone of Chile by the populations located in the north and center, who inhabited the "valley of Chile" (current Mapocho valley), and some regions located to the south of it, thus setting the limits of the Inca Empire in an area that historians and recent archeology conventionally extend somewhere between the rivers Maule and Maipo. Thus, that territory was divided into two wamanis or provinces: the Elqui Valley (Coquimbo) in the north, presided over by Anien, and the Mapocho Valley (Santiago) in the south, headed by Quilicanta.

The Incas in Colombia

In the territory of Colombia, around 1492 the Inca empire temporarily dominated the region inhabited by the aboriginal peoples called Los Pastos and they built a fortress still visible on two roads, in Males (now the municipality of Córdoba). However, the pastures took refuge to the west. in the Awá territory, from where they managed to expel the occupants. The Incas then preferred to advance through the Amazonian foothills through the territory of the Cofán, until they controlled the territory of the Camsá in Mocoa, Valle de Sibundoy and the area of present-day Pasto; but finally it was the Spanish who controlled the region and It was the Awá who managed to preserve themselves from domination in the jungles on the slopes of the Pacific Ocean.

The Incas in Ecuador

In the territory of Ecuador, in the XV century, the Incas Túpac Yupanqui and Huayna Cápac conquered the territory and they incorporated into their empire.

In the middle of the XV century the area was invaded by the forces of the Inca Túpac Yupanqui, who under the command of a powerful army headed from the south to expand their domains. At first the campaign was relatively easy for him, but then he had to face the bracamoros, the only town that could force the Inca to abandon his land without being able to incorporate it into the empire.

When the Inca began to advance on the Cañaris, it was even more difficult for the Inca armies, since they rejected them fighting bravely, forcing them to retreat to the lands of what is now Saraguro, where they had to wait for the arrival of reinforcements to be able to start the campaign. This time considering the immense superiority of the Incas, the Cañaris preferred to agree and submit to the conditions imposed by them. After this, Túpac Yupanqui founded the city of Tomebamba, the current city of Cuenca, the city where it is disputed that Huayna Cápac could have been born.

The Incas in Peru

The Inca Empire originated in the territory of Peru occupying the coast, mountains and high jungle of the Peruvian territory (covering approximately half of its current surface).

At the beginning of the 13th century, Inca history began with Cuzco as the capital, having Manco Cápac as its founder. Since then, the Incas had three expansions, the third being the largest as it developed first to the north starting with central-western Peru to southern Colombia, and then to the south starting with southern Peru to central Chile. In the XV century, the Sapa Inca Pachacútec divided Tawantinsuyo, taking the capital as a point of reference, into four of his own: Chinchaysuyo, Contisuyo, Antisuyo and Collasuyo.

In 1525 a civil war began between Huáscar and Atahualpa for the succession to the throne, Atahualpa winning this dispute, but leaving the empire at odds and unstable. In these circumstances the Spaniards arrive who in Cajamarca surprisingly capture Atahualpa in an interview in 1532.

The Incas in Polynesia

The Spanish chroniclers Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, Martín de Murúa and Miguel Cabello Balboa, during the conquest, collected a series of stories about a trip of the Inca Túpac Yupanqui to distant islands. According to the stories, while the Inca was on the north coast (in the Puná islands), he learned from native merchants who returned to the place, that they arrived sailing on sailing rafts from some very distant islands where there were exotic riches, so he decided to travel myself to check it out. He ordered to prepare a fleet of rafts, and would have sailed from Tumbes, arriving at some islands called Ninachumbi and Ahuachumbi.

Some historians hypothesize that this story has a true historical basis and that the islands would be located in Polynesia. Easter or Mangareva.

Territory of the Inca Empire

The four of them as a whole extended over more than two million square kilometers and came to include, in their heyday (around 1532), part of the current republics of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina. They had approximately four thousand kilometers of coastline in the Pacific Ocean. The expansion began with the Inca Pachacútec and reached its peak with the Inca Huayna Cápac. The maximum expansion is attributed to the Inca Túpac Yupanqui.

To the north, the Inca Empire stretched as far as the Guáitira River, to the north on the border between Colombia and Ecuador. In Ecuador, they came to cover an area that would include the current cities of Quito, Guayaquil, Cuenca and Manta.

To the northeast, it extended to the Amazon jungle of the present-day republics of Peru and Bolivia. Its limits with this are very unclear due to the sporadic exploration expeditions of the jungle by the inhabitants of the empire due to the large number of diseases and the fear that the natives had in those areas, but it is known that they dominated the current ones cities of Potosí, Oruro, La Paz and Cochabamba in Bolivia and practically the entire Peruvian highlands.

To the southeast, the Inca empire even crossed the Andes mountain range (known in modern geopolitics as encabalgarse), reaching somewhat beyond what is now known as the cities of Salta and Tucumán in Argentina. The Inca territory of present-day Argentina formed a special area called Tucma or Tucumán, which included the current provinces of La Rioja, Catamarca, Tucumán, Salta and Jujuy.

To the south, there is evidence that the Inca Empire reached as far as the Atacama Desert (present-day Atacama Region III) in effective control, but with advances as far as the Maule River (present-day Maule Region VII of Chile), where due to the resistance of the purumaucas (or picunches, belonging to the Mapuche ethnic group) it could not continue advancing.

To the west, although the Inca Empire bordered the Pacific Ocean, there are those who also postulate that the Incas would have even maintained, despite the naval limitations of the time, a certain commercial relationship with some unknown people of distant Polynesia (Oceania). The subject has been studied by José Antonio del Busto in a recent publication. One of the people who defended this theory was the late Norwegian diffusionist explorer Thor Heyerdahl.

Its capital was in the city of Cuzco —which, according to the Peruvian Constitution, is the "historical capital" from Peru—, where the four of them were.

Political division: Suyos or regions

The chroniclers affirmed that the Inca empire was divided into four districts known as suyos (from Quechua suyu): Chinchaysuyo, Antisuyo, Collasuyo and Contisuyo. The center of this division was Cuzco itself. The Inca Pachacútec has been attributed the creation of this system of organization of the territory; however we know that it was a practice that preceded the government of this great reformer. Before the Inca domain was consolidated in Cuzco, the space around this city was also divided into four parts. The divisions then corresponded to the territories of the lordships of the area. When Manco Cápac and his clans settled in the area, they created the four Inca suyus from this division.

An issue that is still a matter of discussion among researchers is that of the extension and limits of each suyu. As we have seen, the Inca expansion began with Pachacútec, who conquered the chiefdoms of the area near Cuzco: the soras, lucanas and tambos. Other military leaders such as his brother Cápac Yupanqui, and later Túpac Yupanqui and Amaru Yupanqui, continued the conquests, while Pachacútec remained in Cuzco. For example, Cápac Yupanqui would have recognized and visited the valleys of Chincha and Pisco on the coast, while in the central highlands he would have reached Jauja. Túpac Inca continued the conquest of the Chinchaysuyu up to the region of the cañaris (Tumibamba); while Amaru Yupanqui and other military leaders conquered the Collasuyu up to Chincha and the Contisuyo up to Arequipa. However, we still do not know if the coastal strip between Ica and Tarapacá was conquered at this time or later, after Túpac Yupanqui assumed the supreme command of the Inca State. On the other hand, during the times of Túpac Yupanqui, the northern border was established near Quito; while the southern border was set at the Maule River, 260 km south of Santiago de Chile. During the government of Huayna Cápac, new regions were conquered in Ecuador and the extreme southwest of Colombia (near Pasto). These are generally the known limits of the empire. The least precise point is related to the Amazon region, where it is difficult to specify the scope of the Inca incursions.

Territorial organization

Each province (wamani) was divided into sayas or partes in which a variable number of ayllus lived. The number of sayas in each province used to be based on duality, although it is true that some provinces came to have three sayas, such as that of the Huancas.

The decimal base of administration

For the best administration of the empire, it was necessary to ensure that everyone worked and fulfilled what was imposed on them. To this end, the Incas created a decimal organization that consisted of a school of officials, each of whom controlled the work of ten who were under his immediate authority:

- The Purec or head of family (the basis of society).

- The Chunca-camayocin charge of a ChuncaI mean, the set of ten families. I sent ten. purecs and was responsible for the census of the persons concerned with their jurisdiction, distribute land and direct them at work.

- The Pachaca-camayoc, official apparently equivalent to the healer, who controlled a Pachaca or set of a hundred families. I was in charge of monitoring the chunca-camayocs in the discharge of their obligations and review any decisions they have made in matters within their jurisdiction.

- The Huaranga-camayocin charge of one Huaranga or set of a thousand families. Survigilating the pachaca-camayocs; especially it should take care of the accuracy of the census records and the fairness of the distribution of land, in order to prevent those from taking advantage of their authority to prejudice the well-being of the people.

- The Huno-camayocin command of a Huno or set of ten thousand families, breadth that makes thinking of a tribal confederation stabilized by the authority of the Inca. Survigilating the huaranga-camayocs. He kept the census records and according to them he led the agrarian policy and the handicraft works. He was subordinate to the Tucuirícuc and Suyuyuc Apu.

Political organization

The imperial government was of theocratic monarchical type, the highest authority was the Sapa Inca, advised by the imperial council. Symbol of his power was the mascapaicha, a kind of red woolen tassel that he girdled on his head. He exercised his government functions from the private palace that each one had built in Cuzco. From where he granted audience and administered justice. He also traveled frequently through the Tawantinsuyo, carried on the shoulders of porters, to personally attend to the needs of his people.

The Sapa Inca

These rulers, to whom a divine origin was attributed, are usually associated with the titles inca lord and sapa inca: "divine inca" 3. 4; and "unique Inca", respectively.

The "Capac crib" it was the official list of rulers of the Inca civilization. It is speculated that there were more rulers than it accepts and that several were erased from the official history of the empire for various reasons. In total, there were thirteen Inca sovereigns.

- Legendary Empire: Period without Expansion:

- ~1200 - ~1230: Manco Cápac

- ~1230 - ~1260: Sinchi Roca

- ~1260 - ~1290: Yupanqui

- ~1290 - ~1320: Mayta Cápac

- ~1320 - ~1350: Cápac Yupanqui

- ~1350 - ~1380: Inca Roca

- ~1380 - ~1400: Yáhuar Huácac

- ~1400 - 1438: Viracocha Inca

- Historical Empire: Period of Empire Expansion:

- 1438 - 1471: Pachacútec Inca Yupanqui

- 1471 - 1472: Amaru Inca Yupanqui

- 1472 - 1493: Tupac Inca Yupanqui

- 1493 - 1525: Huayna Cápac

- 1525 - 1532: Huáscar

- 1532 - 1533: Atahualpa

Although some historians consider that Atahualpa should not be included in the capac cradle, arguing that Atahualpa would have declared himself a subject of Carlos I of Spain, in addition to the fact that he was never fitted with the mascapaicha, the symbol of imperial power. But most of the chroniclers give as certain the relation of 14 Incas, assigning the 14th seat to Atahualpa.

Other historians have followed the lineage and consider that Tarco Huamán and Inca Urco should also be taken into account. The first succeeded Mayta Cápac and, after a short period, was deposed by Cápac Yupanqui. Inca Urco girded the mascaipacha by decision of his father, Viracocha Inca, but, faced with his evident misrule and the invasion of the Chancas, he fled with him. After the triumph of Pachacutec Yupanqui -the future Pachacútec Inca Yupanqui, also the son of Viracocha Inca- over the enemy town, Inca Urco was killed in an ambush that he himself set up for his brother. Likewise, Garcilaso and some other chroniclers insert Amaru Yupanqui, a sovereign of doubtful existence, between Pachacútec and Túpac Yupanqui.

Inca Family

La Coya: It is the term that the main wife of the Sapa Inca received, to distinguish her from the rest of the women members of the imperial family as the wife of the emperor. She was the sovereign lady and was above the secondary wives. In the absence of the Inca, she was in charge of the government of the capital, Cuzco. She also organized, in case of need, the aid provided to the victims in case of major catastrophes.

El Auqui: It is the masculine term given to the crown prince in the Inca Empire or Tahuantinsuyo. In a generic way, all the male children of the Sapa Inca were called auquis; however, the specific title fell on only one of them, whose choice was based on criteria different from those of the traditional Western world (his capacity was taken more into account, rather than his quality as firstborn or legitimate son).

La Ñusta: It is the term given to princesses in the Inca Empire. The ñusta was a virgin and daughter of the Sapa Inca. The secondary wives of the emperor were also called that, the equivalent of concubines.

The right of inheritance

Inca political history was almost always plagued by confrontations over hereditary power. This was due to the ambiguity of the criteria for the election of the new Inca.

The main criteria for choosing the new Inca was the rule of choosing the “most skilled”. The new Inca could be the son of the old Inca with the coya or with any concubine. The heirs must be of legal age. The Inca could name a successor, but this had to be accepted by the gods (through an oracle) and by the panacas.

The criterion of choosing the "most skilled" as ruler was a criterion widely spread throughout the territory, many of the macroethnic groups and ethnic groups chose as ruler the one who demonstrated the greatest ability to command and they were not necessarily their own children; This custom was so effective that Viceroy Toledo ordered: "not to do anything new, leaving the succession to the old law and custom".

In the case of the Inca rulers, the most skilled was also the one who won the most supporters in the “panacas”, demonstrating their ability to negotiate politically. This also led to power struggles among the panacas, which led to politically motivated crimes.

In the case of the «panacas», the social status of the mother was important, since everything indicates that the pattern of post-marriage cohabitation in Cuzco was exogamous and matrilineal. In other words, the only thing that differentiated the children of an Inca was his maternal ancestry and it was what gave some more rank than others. In the Inca social network, a mother with numerous kin had a greater capacity to exercise "reciprocity," so important in the Inca social structure.

In general, there were several aspects that prevailed when choosing an Inca sovereign, but the criteria were so ambiguous that in many cases, when one of the Inca's sons proved to be skillful in politics, administration and war, prevailed over his brothers. As examples, Pachacútec prevailed over Inca Urco (Inca Urco was named successor by Huiracocha Inca); Inca Roca was enthroned after the death of Cápac Yupanqui at the hands of his own wife called Cusi Chimbo, a woman who would later be married by Inca Roca himself; Atahualpa prevailed over his brother Huáscar, in a process in which Atahualpa was winning battles and political allies, demonstrating his ability as a ruler. In general, the death of an Inca almost always brought with it a conjunctural period of political instability in which one of the sons had to demonstrate his ability to enthrone himself in power.

Imperial Council

The highest body dedicated to the advice of the Inca sovereign. Composed of eighteen people:

- The four governors of yours (Suyuyuc Apu).

- Twelve advisors, more directly linked to theirs in the Empire.

- The High priest (Willaq Uma).

- The general of the imperial army (Apukispay).

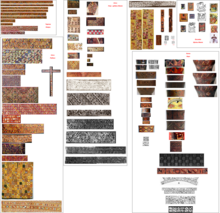

Banner

According to some chronicles, there would have been an Inca imperial ensign or banner (unancha), which has given rise to the argument that there was a kind of flag of the Inca empire. However, such an interpretation is incorrect, since the banner did not represent the Inca state but the sovereign, who painted his weapons and personal insignia on it. In any case, it is known that this banner was used by the Inca hosts together with the sovereign.

The royal script or banner was a square and small banderilla, of ten or twelve palmos of rough, made of canvas of cotton or wool, was placed in the auction of a long stale, lying and stiff, without waving to the air, and in it each king painted his weapons and currencies, because each one of them seemed to be different, though the generals of the Incas were the crowns and the I had the so-called banner certain colored feathers and long layings.Barnabas Cobo, History of the New World (1609)

In contemporary times, the existence of this "Inca banner" has been confused with a multicolored flag (with the colors of the rainbow) that is commonly attributed to the Inca empire. However, according to Peruvian historiography, the concept of a flag did not exist in the Inca empire, and therefore it never had one. This has been affirmed by the historian and researcher of the Inca civilization, María Rostworowski, who when asked about this multicolored banner pointed out emphatically: «I give you my life, the Incas did not have that flag. That flag did not exist, no chronicler refers to it."

Other investigations even indicate that this flag was created only in 1973 to commemorate the anniversary of a radio station in the city of Cuzco called "Radio Tahuantinsuyo", and that its use would have spread from there until the Provincial Municipality of Cuzco It was officially adopted as the emblem of the city in 1978. The Congress of the Republic of Peru itself pronounced itself along these lines, when it pointed out that the origins of this false flag of the Inca empire date back only to the first decades of the XX when some authors, especially indigenistas, mention it and describe it as a supposed emblem of the Inca empire. As Radio Tahuantinsuyo assumed it as the emblem of the radio station, the confusion spread and the error spread massively.

The official use of the so-called Tahuantinsuyo flag is undue and unequivocal. In the pre-Hispanic andean world the concept of flag was not lived, which does not correspond to its historical context.National Academy of History of Peru.

Social organization

The aillu

The word "ayllu" of Quechua and Aymara origin means, among other things: community, lineage, genealogy, caste, gender, kinship. It can be defined as the group of descendants of a common, real or supposed ancestor who work the land collectively and with a spirit of solidarity.

The “aillu” was the base and the nucleus of the social organization of the empire. The aillus believed that they descended from a common ancestor, which is why they were linked by ties of kinship. This ancestor could be mythical or real; and in all cases, the aillus kept a "mallqui" (mummy) to which they worshiped and through which they gave meaning to their relationships. In addition to the mallqui, the members of an aillu had common tutelary divinities and paid tribute to the land in common form.

An aillu owned cattle, land and water to which all its members were entitled as long as they fulfilled obligations established among the members. Each aillu handled the size of their "tupus" (unit of land measurement), each delivered "tupu" had to be worked so as not to lose the right to the land. In the agricultural activity the members of the aillu helped each other; the fact of belonging to the aillu gave them the right to receive help in the event that their own nuclear family was not enough; This help was generally given at harvest time, sowing or in the construction of the houses of the newlyweds; in these cases the "principle of reciprocity" came into play, forcing the return of the aid provided.

In the case of the curaca (head of the “aillu”), he could ask for help to graze his cattle or work the land. He was obliged to provide food and drink to those who helped him, but he was not obliged to return the help, for which reason there was an asymmetrical reciprocity with him.

In the case of communal lands, all the members of the «ayllu» worked it organized by the «curaca» and the «llacta camayoc». The production of the communal lands was stored and redistributed among the members of the aillu who needed it.

Collective work for the construction and maintenance of canals, reservoirs or platforms, was called "minka" and was organized by the curaca, who also assigned the tasks that the members of the "aillu" had to fulfill.

The elderly, widows, orphans and invalids were also obliged to work collectively but received help for the work of their "tupus". Usually the elderly and disabled performed supervisory duties. Poma points out that the irrigation waters were distributed by the elderly.

The aillus not only held land in a compact territory; The need to make an aillu self-sufficient forced it to cover other ecological floors, this gave rise to a discontinuous territoriality that was neither homogeneous nor differentiated. Aillus with large populations could access distant lands and a greater variety of products.

John Murra points out that a good example of this was the Aymara kingdoms, both Collas, Lupacas and Pacajes managed to control discontinuous territories on the coast as enclaves. In places with considerable distances, houses were built that housed the members of the aillu, the members of the aillu took turns working these remote lands.

Although in the highlands of the Inca empire the general characteristic of the aillus was agricultural, there were agricultural and livestock aillus at the same time and others that were only livestock. The eminently cattle aillus were located in Chinchaycocha and Collao; these aillus were dedicated to raising llamas and alpacas from which fiber was obtained; fresh meat or dried meat that was called "charqui"; skins for making “flip flops”, straps, bags and ropes; bones to make needles, musical or other instruments; and "taquia" (excrement) for fuel. On the coast, the aillus had populations specialized in agriculture, trade, fishing, and crafts.

Duality

The basic organizational principle of the Inca society was duality, this duality was based on kinship relationships. The aillus comprised two divisions that could be "hanan or urin", "alaasa or massaa", "uma or urco", "allauca or ichoc"; according to Franklin Pease these words were understood as "high or low", "right or left", "male or female", "in or out", "near or far", and "in front or behind".

The Spanish chroniclers described the curacas in pairs but without specifying the duality because this form of organization was unknown in Europe. In 1593 curacazgos divided into two halves were described, in which each half had a curaca in front; this situation was described for the curacazgos of Acarí, Lima and the curacazgos Lupacas del Collao and Tarata.

There were also curacazgos where women governed with their "second person", these data came from the curacazgos of Colán. The same thing happened in Cuzco, basing its organization on the principle of duality.

Europeans documented Cuzco dynasties: «Hanan Cuzco» and «Urin Cuzco», describing them as successive dynasties into which Cuzco was divided; the Spanish were unable to identify the dual government, so they placed one "dynasty" as an antecedent of the other. In other regions of the empire, other names were preferred for the parts of the duality; the Aymara regions preferred "alaasa - masaaa", other groups close to Lake Titicaca preferred "uma - urco" indicating distance or proximity to water sources (lake or rivers); to the north of the territory "allauca - ichoc" (left-right) was preferred.

The functions of each part are unclear. The chronicles do not describe the specific functions fulfilled by the ethnic leaders of each moiety. What is described is that one of the chiefs was subordinate to the other; Rostworowski describes that in the case of Cuzco the upper half was more important but in the case of Ica the lower half was.

Pease points out that both halves were integrated by reciprocity. In Cuzco, "hanan" and "urin" were opposite and at the same time complementary like human hands ("yanantin"). Even so, it is difficult to deduce what the functions of each part were, the only thing that remains clear is that both parties complemented each other and there were reciprocal obligations between them.

Social classes in the Inca empire

Inca society was hierarchical and rigid. There were great differences between social classes, these differences were respected by all the inhabitants of the empire. The hierarchical classes formed a pyramid where the Inca, with all the power, was at the top (flat), while the people, who were the vast majority, constituted their social base.

| Social classes | Representatives |

|---|---|

| Royalty |

|

| Nobleza |

|

| Aillu |

|

The Inca nobility

In the empire there were two main lineages, Hanan Cuzco and Hurin Cuzco, from which the Sapa Inca or monarch came. Every time an Inca died there was political instability between these two lineages and the descendants of the last monarch in power. When the new Inca was instituted, he formed a new lineage of his own or panaca. There were at least a dozen panacas in the empire, whose members had various privileges.

Although the Sapa Inca, the Coya (his wife), the Auqui (inca's heir) and their children (first generations of each panaca) made up the royal family or royalty of the empire, there was a significant number of people who He considered them noble, whether by blood or privilege. Among the nobles of blood were the remaining members and descendants of the panacas and within the privileged nobles were those people who stood out for their services. One of its characteristics that differentiated the Inca nobility from the town was the enormous size of their ears, caused by the use of expander rings.

The nobility of blood in the Inca empire is estimated at the time of its fall in more than 10,000 individuals distributed in different parts of the territory, who fulfilled administrative and military functions. Part of the strategies used by the Incas to subdue other peoples, after military confrontations, was to establish marriage alliances between the local caciques and the Inca's daughters or concubines in order to create ties that would allow for peaceful occupation. It was also customary for the cacique to deliver his daughters to the Inca, who were sent directly to Cuzco to form part of his harem.

With the fall of the empire, all existing Inca noble prerogatives were lost, however, some nobles made efforts to have them recognized by the Spanish crown, such as Cristóbal Pariacallán Tuquiguaraca, who was granted a coat of arms and privileges, Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala and Inca Garcilaso de la Vega also made efforts to have their class distinctions recognized.

The panacas

The panacas were lineages of the direct descendants of a reigning Inca, excluding the successor, and they kept the mummy of the deceased Inca, as well as their memoirs, quipus, songs, and paintings in memory of the deceased. generation to generation.

These royal panacas formed the Cuzco elite. They had a role in the Inca politics and their alliances and enmities were crucial to the history of the Inca capital. It is said that there were other panacas, which played an important role in earlier times. A curious note about the panacas is that if you add the traditional panacas, you get a total of eight panacas for each dynasty, which is a frequent number in the Andean organization of the aillus because it is a multiple of the duality and of the quadrupling.

| Pancake | Inca |

|---|---|

| Pancake Chima | Manco Cápac |

| Pancake raura | Sinchi Roca |

| Awayni panaca | Lloque Yupanqui |

| Usca Mayta panaca | Mayta Cápac |

| Apu Mayta Canpac panaca | Cápac Yupanqui |

| Pancake | Inca |

|---|---|

| Wikak'iraw pancake | Inca Roca |

| Awkaylli pancake | Yáhuar Huácac |

| Suqsu pancake | Viracocha Inca |

| Hatun ayllu | Pachacutec |

| Cápac ayllu | Tupac Yupanqui |

| Pancake tube | Huayna Cápac |

Hatun Rune

They were the bulk of the population that began their service to the state at the age of majority, hence its meaning "elderly man". They were the common population of the Inca empire that were dedicated to the activities of cattle raising, agriculture, fishing and crafts; they were the labor force. They could be disposed of to serve in the army and work the state lands, they could also be named "mitimaes" or "yana".

Until before getting married, parents were the ones who assigned work to their children. After the marriage, the man acquired responsibilities with the state. After marriage, the "hatun runa" owed benefits to the state for their entire lives. But before that, the children were having minor obligations that were increasing in responsibility with age. There were adolescents who were entrusted with the task of hauling loads for the state and the army; older adults were entrusted with auxiliary tasks in which greater judgment was required.

According to chronicles by Pedro Pizarro, the hunchbacks would have been used as court jesters and the women accompanied their men in rendering services, both for war and for agricultural work.

The Mitimaes (Mitmaqkuna)

They were settlers who were transferred to other regions together with their families and under the command of their ethnic chief, these populations remained in remote territories for a determined time fulfilling tasks assigned by the state or by their own chiefs. These groups did not lose their communal rights, they also maintained ties of reciprocity and kinship. According to the chronicles, the "mitmaqkuna" kept their dresses and headdresses used in their towns of origin, and they also moved taking their goods with them.

The institutionality of the «mitmaq» existed before the Inca expansion, and arose from the need of the Andean peoples to access other ecological levels and exploit various resources that would complement their diet. During the period of greatest expansion of the empire, there were transformations in the institutionality of the "mitmaq", since the migratory movements were made over longer and more massive distances, preventing the group of "mitmaqkuna" from continuing in contact with their nucleus of origin.

These were transplanted populations with the aim of producing goods that would later be redistributed. In some cases the population was transferred as a sign of trust and in others as punishment; the difference lay in the living conditions of each other (punished and rewarded). Cieza de León affirms that there were members of the Cuzco elite who were transferred with their families to teach the Inca language and traditions, these were chosen as a sign of trust and were given "chacras", houses, gifts, luxury objects, honors and even women as a reward for having to travel far from Cuzco.

Yanaconas

The Yanaconas (yanakunas) or simply Yanas, are a population group that is difficult to define as they were populations extracted from their ethnic group for specific tasks but in some cases they had important governmental functions arriving, in some cases, to be curacas and even have "acllas" granted by the Inca.

Basically, the "yanakuna" were a population chosen for their abilities to provide a special service, Yanakuna groups taken from Chan Chan to Cuzco for their metallurgical services are documented, as well as Cañaris groups transferred to the Yucay valley for the cultivation of corn. In the case of the corn production of the cañaris of Yucay, it served for direct feeding of the panacas from Cuzco.

The institutionalization of this population group is documented through stories collected by European chroniclers. According to some accounts, the "yanas" were a population that rebelled and whose lives were spared in exchange for perpetually serving the Inca sovereign. This rebellion took place in Yanayaco; according to legend, just as they were about to be executed, Mama Ocllo interceded for them and asked them to be at his service. According to Rostworowski, the Inca delivered the Yana population to the "coya" when he got married.

The “yana” population was also handed over by the Inca to other curacas for special services, in this case they did what the person in charge ordered. The yanas were distributed throughout almost the entire empire, "yanas" are documented in the care of the mummies of the Inca sovereigns; Likewise, the sun and the huacas had "yanas" at their service (Cieza de León describes the yanas in charge of the huacas of "Huanacaure" and "Huarochirí").

The first Europeans identified the “yanas” as populations without rights, comparing them with the conception of slaves that existed in Europe in those years. However, there is information that rules out this possibility that was published by J. Murra; this information indicates that the "yanas" had the right to receive land for their livelihood. Research by W. Espinoza indicates that the status of "yana" was common before the empire and their number increased as the territory expanded.

Pineapples

Some scholars identify them as slaves, and despite not appearing in the chronicles, it is known about them because they were described in Quechua dictionaries. According to research by Rostorowsky, these dictionaries mention that the "pinakuna" were prisoners of war and occupied a lower level on the Inca scale. According to W. Espinoza, he points out that the institutionalization of the "piñakuna" is late and the one who institutionalized it was Huayna Capac; From this period on, all those prisoners of war who did not admit his defeat became part of the "piñakunas". This happened with some groups of pastures, carangues, cayambes, quitos, cañaris and chachas.

The situation of the "piñacunas" was extensive for their partners and children, remaining the property of the Inca state, sending them to work in areas of difficult access, generally in coca fields in the mountain jungle; there is evidence that the state also provided them with land for their own subsistence.

Population control system

The Incarios extended their rule under different ethnic groups. It is estimated that the total population of the empire was between 16 to 18 million, depending on the sources.

| Chargé d ' affaires | Number of families |

|---|---|

| Pureq or Purej | 1 family |

| Pisca camayoc | 5 families |

| Chunka bedyoc | 10 families |

| Pisca chunka camayoc | 50 families |

| Pachaka bedyoc | 100 families |

| Pisca pachaka camayoc | 500 families |

| Huaranka bedyoc | 1000 families |

| Pisca huaranca camayoc | 5000 families |

| Huno camayoc | 10 000 families |

Economic activities

Upon reaching the Inca empire, the Spanish agreed to highlight the success of their economy. The chroniclers described the products they found in the deposits, praising the abundance of production both in agriculture and in livestock; Europeans also praised the equitable distribution of these products among the population.

The chronicles agree that the success of the Inca economy was based on a correct administration of resources, to make this administrative form effective, warehouses were built and quipus were used as an accounting system.

Although the chronicles mention that the wealth of the Incas was based on the delivery of tributes, recent research shows that this was not the case; rather the success of the empire was achieved in a correct administration of the workforce, Pease affirms that this achieved that the state has the necessary production for redistribution.

The work for redistributive production was rotating (mita) and was delivered periodically by the ayllus of the Inca empire. This system was not an Inca creation, since it was based on traditional forms of administration. The Incas took this system to its maximum expression, storing production and redistributing it according to state needs and interests.

The base of the economy was agriculture; the lands were communal. Each family had their land to cultivate and feed themselves. The most numerous families, received more land.

The way of working the land was the minka, that is, "they helped each other in agricultural tasks in a community way." The Fuenterrebollo Portal tells us that "... well when an individual had so much work that he could not handle it, or in the case of orphans, the sick and widows." «When certain necessary species could not be cultivated (potatoes, for example), part of the community settled in other areas. This way of obtaining resources was known as "ecological complementarity".

The basic diet of the Incas was potatoes and corn, supplemented with meat of auquénidos: llama and alpaca. In the highlands of the Andes, up to 200 species of potatoes, differing in color and size, were grown and harvested. To avoid their decomposition and for the purpose of storing them or for feeding their large army, especially when they went out on campaigns, they learned to dry and cut potatoes (lyophilization), a product called Chuño, then, before consuming them, they hydrated them again and they were cooked They supplemented this diet with other vegetables such as olluco, oca, tomato, beans, pumpkin, chili, peanuts (from which they also extracted oil), quinoa and fruits.

The Incas not only cultivated flat or semi-sloping land, they used an ingenious system to cultivate the slopes of the hills, this technique consisted of forming terraces, called “andenes”, which they filled with topsoil that was contained with walls of stone. In addition to the wool provided by the auquénidos, they planted, harvested and used cotton to make their clothing. In the lands corresponding to the high jungle, they planted and harvested the “sacred leaf”: coca.

They caught various species of fish and hunted wild birds. To maintain such a large amount of planted land, the Incas were great hydraulic engineers: many of the irrigation canals in the sierra still work perfectly today and irrigate the new farmland.

Land tenure

The possession of the land was a right that the settlers had for belonging to a certain ethnic group. The curacas distributed the land according to the needs of the individuals and their families. The unit of measurement was the "tupu", but the dimensions of the "tupu" could vary according to the yield of the land. According to this, a domestic unit received 1 1/2 tupu, when a male child was born they were assigned an additional tupu and if a woman was born they were assigned an additional 1/2 tupu; if the children married, the additional tupus were withdrawn from the family.

Some chroniclers indicate that the distribution of the lands was annual, Guamán Poma points out that this distribution was made after the harvest in the eighth month of the Inca calendar and that this activity received the name of "chacraconacuy" (this corresponded to the months of July and August). John Murra points out that this annual ceremony was a land reaffirmation ceremony and that there was continuity in land tenure by each family. The "chacraconacuy" ceremony contemplated the fertilization of the land, the cleaning and repair of canals and ditches, as well as sacrifices to the "pachamama".

The chronicles state that after a conquest, land and livestock were declared "state property" and that they were later ceded to the conquered populations. In reality, land tenure after a conquest was conditioned by the wealth and resources that existed in that territory. Tuber growers were generally allowed to continue to own their land; On the other hand, it was common for groups that produced corn and coca to have their lands expropriated to dedicate them to the state or to cults, taking into account that this production was especially important for the Inca religion.