Inca

Sapa Inca (from Quechua: Sapan Inka) or simply Inca (from Quechua: inqa or inka, 'inca') was the ruler of the Inca Empire, whose domain initially extended to the curacazgo of Cuzco and later to Tahuantinsuyo, a political entity that existed in the Western South America from the 13th to the 16th century. The term Cápac Inca was also used (from Classical Quechua: Khapaq Inka, 'the mighty Inca').

The first sinchi from Cusco to use the title of sapa Inca was Inca Roca, founder of the Hanan Cuzco dynasty. The last Inca to rule independently was Atahualpa. After the Spanish conquest he continued to name himself titular Incas for a short time. And later, the title was used by the leaders of the resistance against the Spanish, such as Manco Inca or Túpac Amaru I, who are known as the Incas of Vilcabamba.

The center of the empire, and residence of the Incas, was in Cuzco. Members of Inca society considered their rulers to be the descendants and successors of Manco Cápac, the mythological founder and cultural hero who (according to the Inca point of view) ushered in civilized life in the Andes, and on whom the political regime rested for its legitimacy. Inca. According to the chroniclers of the Indies and the testimonies of some Spanish conquerors such as Francisco Pizarro, the power of the Inca was absolute; For this reason, he was the owner not only of the lands of Tahuantinsuyo, but of everything that was within his limits, including the lives of his subjects. After approximately a century of existence, the Tahuantinsuyo began its disappearance with the arrival of the Europeans.

Inca society

In Cuzco in 1589, the last survivor of the Spanish conquistadors of Peru, Mancio Serra de Leguisamo, wrote the following in the preamble to his will:

We found these kingdoms in such a good order, and they said that the Incas governed them in such a wise way that among them there was no thief, nor a vicious, nor an adultererer, nor was there a bad woman among them, nor was there immoral persons. Men have useful and honest occupations. The lands, forests, mines, pastures, houses and all kinds of products were regulated and distributed in such a way that everyone knew their property without another person taking it or occupying it, and there were no demands on it... the motive that compels me to make these statements is the release of my conscience, as I find myself guilty. Because we have destroyed with our evil example, people who had such a government that was enjoyed by their natives. They were so free from imprisonment or crimes or excesses, men and women alike, that the Indian who had 100,000 weights of gold left it open merely leaving a small stick against the door, as a sign that his master was outside. With that, according to their customs, none could enter or take anything that was there. When they saw that we put locks and keys in our doors, they assumed that it was for fear of them, that they might not kill us, but not because they believed that anyone could steal the property of the other. So when they discovered that we had thieves among us, and men who sought to make their daughters commit sins, they despised us.

Choice of the Inca

The chronicles identify the Inca as the supreme ruler in the likeness of European kings in the Middle Ages. However, access to this position did not have to do with inheritance to the eldest son, but with the choice of the gods through very rigorous tests, to which the physical and moral aptitudes of the suitor were subjected. Such tests were accompanied by a complex ritual through which the god Inti nominated who should assume the Inca position. The god Inti, if he agreed, gave the power of rain to the future Inca. Over time, the Incas named their favorite son as co-ruler with the intention of ensuring his succession, for example, Huiracocha Inca associating Inca Urco to the throne.

Functions

The Inca accumulated in his person the political, social, military and economic direction of the State. They ordered and directed the construction of great engineering works, such as Sacsayhuamán, a fortress that took 50 years to finish; or what was the urban plan of the cities. But his most important work was the network of roads that crossed the entire empire and allowed rapid travel for administrators, messengers and armies equipped with suspension bridges and tambos. They must always be supplied and well cared for They founded military colonies to expand their culture and control and ensure the maintenance of said network. In Cuzco they were also curacas, in charge of the roads and cleaning irrigation canals.

At a religious level, they promoted the cult of Inti, considered the father of the Inca, or they organized the calendar, indicating the days of festivals and sacrifices. At a political level, they sent inspectors to monitor the loyalty and efficiency of officials. The monarchs promoted a unified and decentralized government where Cuzco acted as the articulating axis of the different regions of theirs. They appointed highly trusted governors. On the economic level, they decided how much each province should pay according to their resources. They knew how to win over the curacas to ensure control of the communities. These were the intermediaries through whom they collected tribute.

The Sapa Inca must have been a warrior. By tradition, every time one died, his successor was disinherited because his father's lands, houses and servants passed to his other children. The new sovereign had to get land and booty to bequeath to his own descendants, producing a perpetual process of territorial expansion.Every time they subdued a town, they demanded that the defeated leader hand over part of his land to continue his command.

Symbols of distinction

The Inca was deified, both in his actions and his emblems. In public he carried the topayauri (sceptre), ushno (golden throne), suntur páucar (feathered pike) and the mascapaicha. In religious ceremonies he was accompanied by a white llama (considered sacred), the napa, covered with a red gusset and adorned with gold earmuffs. There is also talk that they carried the llauto.

A sacred being

He was considered a divinity and representative of the State. Called "son of the Sun", Intichuri, and "benefactor of the poor", Huaccha Khoyaq. He traveled seated on a wooden throne carried by litter bearers (ushnu ) because as a god he could not walk. He was always accompanied by his servants. He changed his clothes 4 times a day, he was served by his sister and his young noblemen, he used to eat alone or accompanied by his favorite son. Everything that the Sapa Inca touched was kept with extreme care and burned on a certain day of the year. In his presence the subject had to bow carrying a weight on his back, as a sign of submission. No one could look him in the eye, raise his head or speak to him without permission. Common people could not pronounce his name like anyone else's. When he passed through a town, people went to the mountains and from there they offered him coca, fruits and other gifts. If they had nothing, they would pluck off their eyelashes and throw them in the direction of the monarch.

When he died, the corpse of the monarch was considered sacred, his funeral could be accompanied by sacrifices of some wives, servants and above all llamas, the brown ones to honor Viracocha and the white ones for Inti. His body became malqui, a “mummy”. In order to care for and revere this mummy, his descendants formed a panaca, a true group of power that possessed land, servants and palaces, and who claimed to be able to communicate with the deceased through a specialized servant, to tell the present Sapa Inca his opinions and mandates on imperial policy. They were the imperial elite and monopolized priesthoods, high-ranking military chiefs, and top administrators. They were collectively nicknamed collana and their servants payan (and non-Incas cayao). When Huayna Cápac died in the north of the empire, he was embalmed and taken on a litter to Cuzco well dressed, armed and with his topayauri, arriving at the capital in a great party. The worst insult for them was to destroy the mummy they served, something that Atahualpa did when he conquered Cuzco, allowing his soldiers burn the mummy of Túpac Yupanqui.

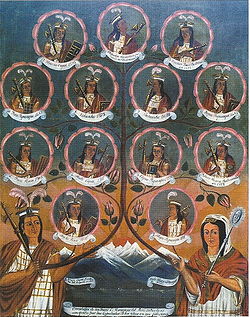

List of Incas

The official list of Inca rulers was written by colonial chroniclers and is called Capaccuna. In Quechua it was Qapaqkuna. It comes from Cápac, translatable as "lord" or "mighty", and Cuna, plural suffix, meaning "the lords". Such a list is accepted by contemporary historians, although many point out that it probably several were expunged from this official history. It is possible that it was a diarchy, with a senior emperor sharing power with his most trusted brother or son, as these were first in line in early times. Hence, many rulers were forgotten. This binary system was customary among the Andean peoples and among the Cuzqueños. The first indication appears with Manco Cápac and Ayar Auca Also, if an Inca came to the throne at an early age, as happened with Mayta Cápac, two regents were appointed among the closest relatives until he reached the age of majority.

Hurin and Hanan Cusco

They were grouped in Hurin Cuzco, «Lower Cuzco», and Hanan Cuzco, «Upper Cuzco». The Inca capital was divided into these two halves separated by the Antisuyo road and populated by factions that disputed political power. The first rulers were Hurin, but according to the chronicler Martín de Murúa, when the Inca Cápac Yupanqui died, apparently poisoned by his concubine Cusi Chimbo, daughter of the sinchi or "lord" of Ayarmaca, who became his second wife. The moment was seized by the conspirators led by Inca Roca, who attacked the Inticancha palace, deposed the Hurin and installed the Hanan as monarchs. Finally, a balance would be reached. The Hurin retained religious power, property, and treasures comparable to the secular. Political, civic, economic, social and military affairs were left to the Hanan, but this does not mean that a diarchy formed between them.

Incas of Tahuantinsuyo

According to Juan de Betanzos, the Capaccuna were Manco Cápac, Sinchi Roca, Lloque Yupanqui, Mayta Cápac, Cápac Yupanqui, Inca Roca, Yáhuar Huácac, Huiracocha Inca, Pachacútec Inca Yupanqui, Amaru Inca Yupanqui, Túpac Inca Yupanqui, Huayna Cápac, Huáscar and Atahualpa. Tarco Huamán, successor to Mayta Cápac, has been excluded because he was deposed shortly after by his cousin Cápac Yupanqui. The latter was so feared that the Ayamarca sinchi sent his daughter to him Another was Inca Urco, favorite son of Huiracocha Inca, he fled with his father when the Chancas attacked and when his brother Cusi Yupanqui seized power he tried to claim his rights, being defeated and executed. Amaru Inca Yupanqui or simply Inca Yupanqui, was the heir of Pachacútec. According to some sources he came to the throne but his weak and peaceful character led to his overthrow and replacement by his brother Túpac Inca Yupanqui. Despite this, he was always loyal to his brother. According to others, he was co-ruler with his father, but his poor performance caused him to be relegated by his younger brother. It is also stated that the nobles never accepted Amaru and after his proclamation he was deposed by someone more like-minded.

The laws of succession were established by Túpac Inca Yupanqui, maintained by the Cápac ayllu, an institution formed by his descendants. He also established a ceremony for the granting of the title of auqui to the young members of the royal family. It was the equivalent of a prince and among them the ruler chose his heir, who should be the son conceived with the main wife. The latter was called Mama-ocllo, while a coya was a secondary and a chipa-coya as a concubine. Nobles were called ñusti (men) or ñusta (women). Virtually all Inca (members of the royal family) were auqui the males or coya the females.

The little age of the Cápac ayllu prevented it from imposing itself on the claims of the Tumipampa ayllu, a rival family formed by the descendants of Huayna Cápac in the north. This would also be an expression of the growing rivalry between the old imperial capital (Cuzco) and the new center of power (Tumipampa). The last great Sapa Inca, Huayna Cápac, named Ninan Cuyuchi his heir, but a smallpox epidemic killed him. to that prince in Tumipampa but before the news reached his father the disease took his life in Quito. The succession chaos led to the enthronement of Huáscar. Meanwhile, another son of his, Atahualpa, was already curaca in Quito. Their mistrust of one another led to the Inca civil war.

After summarily executing Atahualpa, Francisco Pizarro named Tupac Hualpa the new Sapa Inca, making the Spanish presence more acceptable to indigenous eyes, but he was soon assassinated. In 1533 Pizarro chose Manco Inca Yupanqui, another son of Huayna Cápac, who tried to collaborate with the Europeans, but in response to their demands he revolted in 1536. The battle of Sacsayhuamán took place in which he was defeated and forced to escape into the jungle. To replace him, his brother, Paullu Inca, who was a puppet until his death in 1549, after which the Inca rule was officially abolished, was crowned.Manco Inca Yupanqui founded a government in exile, in Vilcabamba. He was succeeded by his sons Sayri Túpac, Titu Cusi Yupanqui and Túpac Amaru I, one after another, until the fall of Vilcabamba to the Spanish in 1572.

During the colonial indigenous rebellions some leaders proclaimed themselves Sapa Inca. Juan Santos, descendant of Atahualpa, proclaimed himself Atahualpa Apu Inca in 1742, fourteen years later he fled into the jungle. Túpac Amaru II, descendant of the last son of Manco Inca, proclaimed himself Túpac Amaru II in 1780 and was executed in 1781, during his rebellion.

Timeline

Since the 1980s, the chronological estimate of the Sapa Incas has improved considerably, which, like all peoples without writing, is inaccurate and mixed with legends. The most supported dates currently are based on research and comparisons and are always approximate. Three decades earlier, it had begun to be considered that the Incas had begun around 1450. José Antonio del Busto in his Inca Peru established a distinction between the legendary and historical Incas, although in an unclear way. Federico Kauffmann Doig (Manual of Peruvian Archaeology), Carl Grimberg (Universal History), Henry Pease García (The Incas) and Geoffrey Barraclough (Atlas of Universal History) estimate that the empire lasted less than a century. A very short period of time for the level of expansion and development achieved by the Tawantinsuyo, which further highlights the reforms that Pachacútec carried out when he assumed power. On the other hand, the Peruvian anthropologist Luis Lumbreras contradicts himself, in some studies he indicates that the Incas began around 1430 but in others he indicates that it lasted 250 years until its conquest.

All dates prior to the arrival of the Spanish are difficult to calculate and defend because the Incas did not systematically record the passing of the years. American archaeologist John Rowe is based on the Cabello Balboa chronicles, but he himself criticizes the years that the chronicler gives as resulting in too long reigns; his chronicle is a "mythical-historical continuum" and the Curacazgo of Cuzco must be considered largely mythical. Later, he compared the chronicle with archaeological data. The founding of Cuzco must have occurred sometime between 1200 and 1300, following a period from mythical Sapa Incas to Cápac Yupanqui, from which monarchs are most likely to exist until Huiracocha and Pachacútec, who are the earliest historical ones. In fact, the earliest exact date Rowe accepts is 1438, during the Chanca invasion. and the overthrow of Huiracocha Inca by Pachacútec. However, he refuses to date the enthronement of the deposed.

Taking Rowe (1944 and 1945) and anthropologist Susan A. Niles (1987), Pachacútec reigned from 1438 to 1471, when he was succeeded by Túpac Yupanqui, ruler until he died in 1493. His successor, Huayna Cápac, continued in command until 1528, leaving the government to Huáscar, who was deposed by Atahualpa in 1532. Additionally, it has been estimated that Túpac Yupanqui began to co-rule with his father in 1463. These years have been taken as "definitive years" by the most of the current literature, which is open to criticism, since the debate has not yet been closed thanks to new technologies, such as radiocarbon dating.

Busto, a Peruvian historian, establishes the foundation date of Cuzco in 1285. The first Inca would have died in 1305, his successor is part of the "Legendary or Curacal Period". In 1320 the «Proto-historical or Monarchical Period» begins and covers from the third to the eighth reign. The Hanan would have seized power in 1370. In 1425 Pachacútec came to power, co-ruled with his son Amaru Yupanqui since 1467. Túpac Yupanqui reigned alone between 1471 and 1488. Huayna Cápac remained in charge until his death from him in 1528.

Historian María Rostworowski affirms that Pachacútec reigned for forty years. He was associated with his sons Amaru Yupanqui and Túpac Yupanqui for five or six and fourteen or fifteen years respectively. Subsequently, the latter would have governed for only ten more.

Chronology of the Historia de los Incas by Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, original from 1572. Currently, Sarmiento's dates are harshly criticized because they do not coincide with the archaeological evidence, he skips large periods of time between monarchs (usually considered father and son) and some reigns exceed one hundred years (something impossible for the living conditions of that time).

| Order | Inca | Birth | Queen | Duration | Order | Inca | Birth | Queen | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Manco Cápac | 521 | c.565-656 | 100 years | VII | Yahuar Huácac | ≥1069 | 1088-1184 | 96 |

| II | Sinchi Roca | 548 | 656-675 | 19 | VIII | Huiracocha Inca | ≥1166 | c.1184-1424 | ? |

| III | Lloque Yupanqui | 654 | 675-786 | 111 | IX | Pachacutec | 1400 | 1425-1471 | 46 |

| IV | Mayta Cápac | 778 | 786?-890 | 104? | X | Tupac Inca Yupanqui | 1173 | 1471-1488 | 17 |

| V | Cápac Yupanqui | 876 | 891-985 | 89 | XI | Huayna Cápac | 1444 | 1489-1528 | 39 |

| VI | Inca Roca | 985 | 1088? | ? | XII | Huáscar | 1493 | 1523-1532 | 9 |

Chronology based on the works Sum and Narrative of the Incas by Juan de Betanzos (1551) and El Señorío de los Incas by Pedro Cieza de León (1880).

| Order | Inca | Queen | Order | Inca | Queen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Manco Cápac | 1240-1260 | VII | Yahuar-huaccac | 1360-1380 |

| II | Sinchi Rocca | 1260-1280 | VIII | Uira-cocha | 1380-1400 |

| III | Lloque Yupanqui | 1280-1300 | IX | Pachacutec Yupanqui | 1400-1440 |

| IV | Mayta Ccapac | 1300-1320 | X | Tupac Yupanqui | 1440-1480 |

| V | Ccapac Yupanqui | 1320-1340 | XI | Huayna Ccapac | 1480-1523 |

| VI | Inca Rocca | 1340-1360 | XII | Inti Cusi Hualpa | 1523-1532 |

Chronology according to the Miscelánea antártica by Miguel Cabello Balboa, original from 1586. It is highly criticized for the length of several reigns and for the fact that it does not coincide with the archaeological studies. Includes correction by Howland Rowe (and accepted by Kauffman Doig, Ann Kendall, Alden Mason, and Robert Deviller).

| Order | Sapa Inca | Date of reign | Duration | Review | Order | Sapa Inca | Date of reign | Duration | Review |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Manco Cápac | c.945-1006 | 61 | 1200-1230 | VIII | Viracocha | 1386-1438 | 50 | 1410-1438 |

| II | Sinchi Roca | 1006-1083 | 77 | 1230-1260 | IX | Pachacutec | 1438-1473 | 35 | 1438-1471 |

| III | Lloque Yupanqui | 1083-1161 | 78 | 1260-1300 | X | Tupac Yupanqui | 1473-1493 | 20 | 1471-1493 |

| IV | Mayta Cápac | 1161-1226 | 65 | 1300-1320 | XI | Huayna Cápac | 1493-1525 | 32 | 1493-1528 |

| V | Cápac Yupanqui | 1226-1306 | 80 | 1320-1350 | XII | Huáscar | 1525-1532 | 7 | |

| VI | Inca Roca | 1306-1356 | 50 | 1350-1380 | XIII | Atahualpa | 1532-1533 | 1 | |

| VII | Yahuar Huácac | 1356-1386 | 30 | 1380-1410 |

Chronology according to the History of the Kingdom of Quito in South America by Juan de Velasco. Work of five volumes published between 1790 and 1792. Names of monarchs according to author. They are currently questioned because they do not coincide with archaeological studies and traditionally accepted dates of events.

| Order | Sapa Inca | Queen | Duration | Notes | Order | Sapa Inca | Queen | Duration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Manco Cápac | 1021-1062 | 40 years | IX | Inca-Urco | 1340 | 11 days | ||

| II | Sinchi-Roca | 1062-1091 | 30 | X | Pachacocotec Inca Yupanqui | 1340-1400 | 60 years | Titu-Manco-Cápac before being Inca. He died at 103. | |

| III | Lloque Yupanqui | 1091-1126 | 35 | XI | Amaru Inca Yupanqui | 1400-1439 | 39 | ||

| IV | Mayta Cápac | 1126-1156 | 30 | XII | Tupac Inca Yupanqui | 1439-1475 | 36 | ||

| V | Cápac Yupanqui | 1156-1197 | 41 | XIII | Huayna Cápac | 1475-1525 | 50 | Kingdom only the Empire the first 12 years; the other 38 together in Quito. | |

| VI | Inca Roca | 1197-1249 | 51 | XIV | Huáscar | 1526-1532 | 7 | ||

| VII | Yaguar-guácac | 1249-1289 | 40 | Deposed by his successor. He died in private in 1296. | XV | Atahualpa | 1532-1533 | 1 year 4 months | He reigned only in Quito 6 years 4 months; all the Empire 1 year 4 months until his death (counting while in jail) |

| VIII | Huiracocha | 1289-1340 | 51 |

The chronology according to the studies of the Peruvian anthropologist Manuel González de la Rosa.

| Order | Sapa Inca | Queen | Order | Sapa Inca | Queen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Sinchi Roca | 1131-1197 | VI | Yahuar Huácac | 1348-1370 |

| II | Lloque Yupanqui | 1197-1246 | VII | Huiracocha | 1370-1425 |

| III | Mayta Cápac | 1246-1276 | VIII | Pachacutec | 1425-1478 |

| IV | Cápac Yupanqui | 1276-1321 | IX | Tupac Yupanqui | 1478-1488 |

| V | Inca Roca | 1321-1348 | X | Huayna Cápac | 1488-1525 |

Chronology of the Yungas (also called Yncas or Ingas) according to the polymath Constantine Samuel Rafinesque (names according to the author). Includes main events dated according to his calculations.

| Order | Sapa Inca | Queen | Conyuge | Pancake | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Guanacure (Ayarache) | c. 1080 | Ragua | From the village I played. King of Pacaritambo. | |

| II | Aranaca | c. 1090 | Cona | King of Tamboquiro. | |

| III | Manco I (Maneo Cápac) | 1100-1137 | Oello (Colo) | Chima | Brother of the previous two. Reinado starts by founding Cuzco in Huanacauti. 1107 begins the conquest of neighboring tribes. 1125 have defeated 16 tribes (including collapses and quechuas). Found more than 100 villas. |

| IV | Sinchi Roca | 1137-1167 | Achiola (Cora) | Raura | 1140 beats the pigs and courts. |

| V | Yupanqui I (Yaguarguague or Lloque) | 1167-1197 | Cava | Huaynana | 1170 beat the baskets; ayaviris resist the Inca; with 7,000 troops it beats the sucas. 1175 with 9,000 troops conquers the southern hills. |

| VI | Mayta Capac | 1197-1227 | Cuca | Urcamayta | 1199 conquers Tiahuanaco. 1205 Huychu's battle against the collas and definitive conquest of these. |

| VII | Yupanqui II (Pachuti Capac) | 1227-1257 | Cury Ilpay | Aumayta | 1230 takes 80 Aymara villages with 20 000 soldiers and peace in Chirirqui with the umas. 1236 his brother, Auqui Tito, beats the Quechuas and Yuncas and arrives in the Pacific. 1240 conquers the kingdoms of Zapana (Chipana) and Cora (Cari) on the shores of Lake Paria (end of 400 years of wars between these kingdoms). 1242 conquers Chayanta and Charcas. 1250 Prince Inca Roca conquers Rucana. |

| VIII | Yupanqui III (Roca) | 1257-1305 | Micay | Vicaquirau (Vizaquimo) | 1260 the new king wins a victory over the chancas. 1280 sends 30,000 incas against the chancas. 1285 Yuca Roca founded the Cuzco academy (teach history, chronology, law, philosophy, poetry, etc.). |

| IX | Yupanqui IV (Yahuarhuacac) | 1305-1315 | Chichia | Aylli | 1315 rebellion of the Hancohuallu shawls. |

| X | Huiracocha | 1315-1372 | Runtu | Cos | 1315 30,000 chancas march against Cuzco but they are defeated in Sacsahuana. 1350 Hancohuallu flees from Peru. |

| XI | Urco | 1372-1375 | |||

| XII | Manic II (Pachacutec) | 1375-1425 | Huarca | Incapanaca | 1388 beats Chuquimanco; 1402 beats Cuismanco. 1408 the Chimus are conquered. |

| XIII | Yupanqui V | 1425-1450 | Chimpu | Incapanaca II | 1430 10,000 soldiers launch expedition in the jungles beyond the Andes Found colonies on the banks of the Muzus. 1442 Sinchiroca campaign conquers the Chilean north. 1448 is the battle of the Maule. |

| XIV | Yupanqui VI (Tupac Yaya) | 1450-1481 | Ocllo | Capac | 1457 Tupac Yupanqui conquers the Chachapoyas. 1463 to the Ayahuacas after three years of war. 1466 the Canarines yield. 1477 conquest of Quito by Huayna Cápac after four years of war. |

| XV | Huayna Capac | 1481-1523 | Several | Tumipampa | Reinas Pileu, Riva, Runtu and Toto. 1492 conquest of Tumbes with 50,000 men. 1512 appoints Atahualpa king of Quito. |

| XVI | Huáscar (Inticusi) | 1523-1526 | Unknown | Extermined | |

| XVII | Atahualpa | 1526-1533 | King of Quito. |

Chronology according to O imperio dos Incas: no Perú e no Mexico by the Brazilian Domingos Jaguaribe in 1927 (names according to author).

| Order | Sapa Inca | Queen | Order | Sapa Inca | Queen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Manco Capac | 1118-1147 | VIII | Viracocha-Inca | 1370-1410 |

| II | Sinchi Roca | 1147-1178 | IX | Pochacutec | 1410-1450 |

| III | Lloque-Iupanqui-Capac | 1178-1215 | X | Amaru Yupanqui | 1450-1480 |

| IV | Mayta Capac | 1215-1256 | XI | Tupac-Yupanqui | 1480-1496 |

| V | Capac Yupanqui | 1256-1296 | XII | Huayna-Capac | 1496-1515 |

| VI | Yahuar Huacac | 1296-1337 | XIII | Inti-Hualpa | 1510-1519 |

| VII | Inca Roca | 1337-1370 |

Chronology of the History of Peru according to the Jesuit Santos García Ortiz.

| Order | Sapa Inca | Queen | Duration | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Manco Cápac | 1150?-1178 | 28 years? | Found the empire. |

| II | Sinchi Roca | 1178-1197 | 19 | Expansion south and north. |

| III | Lloque Yupanqui | 1197-1246 | 49 | Conquer the south and east of Cuzco. First armies. |

| IV | Mayta Cápac | 1246-1276 | 30 | Conquests continue. |

| V | Cápac Yupanqui | 1276-1321 | 45 | Extensive conquests. Progress in Cuzco. |

| VI | Inca Roca | 1321-1348 | 21 | Inventa quipos. Build schools for princes. |

| VII | Yahuar Huácac | 1348-1370 | 22 | He has several provincial rebellions. |

| VIII | Huiracocha | 1370-1420 | 50 | He's coming to Tucumán. |

| IX | Pachacocotec Inca Yupanqui | 1420-1477 | 57 | Comes from Arequipa to Cajamarca. |

| X | Amaru Inca Yupanqui | 1478-1478 | 1 | I think of the Mojos fortress. |

| XI | Tupac Inca Yupanqui | 1478-1488 | 10 | Conquer the antis and collas. Get to Maule. |

| XII | Huayna Cápac | 1488-1525 | 37 | Conquest Quito and Pasto. Imperial apogee. |

| XIII | Huáscar | 1525-1532 | 7 | It inherits the kingdom of Cuzco. He's beaten and he dies in jail. |

| XIV | Atahualpa | 1525-1533 | 8 | It inherits the kingdom of Quito. Beat Huáscar. |

Chronology according to the digital educational platform Carta Pedagógica, biographical data published in July 2008.[citation required]

| Order | Sapa Inca | Queen | Order | Sapa Inca | Queen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Manco Cápac | 1150-1178 | VIII | Viracocha Inca | 1370-1430 |

| II | Sinchi Roca | 1178-1197 | IX | Pachacocotec Inca Yupanqui | 1430-1478 |

| III | Lloque Yupanqui | 1197-1246 | X | Amaru Inca Yupanqui | 1478 |

| IV | Mayta Cápac | 1246-1276 | XI | Tupac Inca Yupanqui | 1478-1485/88 |

| V | Cápac Yupanqui | 1276-1321 | XII | Huayna Cápac | 1488-1525 |

| VI | Inca Roca | 1321-1348 | XIII | Huáscar | 1525-1532 |

| VII | Yahuar Huácac | 1348-1370 | XIV | Atahualpa | 1532-1533 |

Contenido relacionado

Pirate (disambiguation)

Ontarian

Culture