Immunology

Immunology is a broad branch of biomedical sciences that deals with the study of the immune system, understanding as such the set of organs, tissues and cells that, in vertebrates, have the function of recognizing foreign elements giving a response (immune response). Science deals with the physiological functioning of both in states of health and disease; alterations in the functions of the immune system (autoimmune diseases, hypersensitivities, immunodeficiencies, rejection of transplants); the physical, chemical and physiological characteristics of the components of the immune system. Immunology has various applications in numerous scientific disciplines, which will be discussed later.

Concept

The word immunity is derived from the Latin term immunitas. So someone immune was understood as exempt or free from taxes (and/or services). Later, in 1879 the French bacteriologist Louis Pasteur coined a new meaning Immünire - ("in from the inside and "munera" meaning ammunition, armament or trench) which is the concept that we understand today: defend yourself from the inside. — is the origin of the word immunity, which refers to the state of protection against infections.

Historical perspective

The discipline of immunology arose when it was observed that individuals recovered from certain infectious disorders were protected against a possible second infection. It is believed that the first reference describing immune phenomena was written by Thucydides, the historian of the Peloponnesian Wars, in 430 BC. no. and. This text describes that during a plague in Athens, only those who had recovered from it could care for the sick because they did not contract the disease a second time.

The first recorded attempts to induce immunity artificially were made by the Chinese and Turks in the 15th century when trying to prevent smallpox. Reports describe the process of variolation in which the dried scabs left behind by smallpox pustules were inhaled through the nostrils or inserted into small breaks in the skin.

In 1718, British aristocrat Lady Mary Wortley Montague, after returning from a stay in Turkey, performed variolation on her own children. But it is not until 1796 that the English doctor Edward Jenner, observing the fact that nannies who had contracted cow pustule or cow mammary pustule disease (a mild disease) remained immune against smallpox, reasoned that by introducing fluid from a bovine pustule in a person (inoculation) could protect against smallpox. He verified the hypothesis by inoculating an eight-year-old boy with fluid from a cow pustule and then intentionally infecting him with smallpox; the child did not present the disease.

Louis Pasteur, with his assistants Charles Chamberland and Émile Roux, succeeded in culturing the bacterium that causes cholera in chickens and verified the participation of this microorganism when chickens inoculated with it died. Pasteur went on vacation and left his laboratory with his bacterial cultures, which over time lost their pathogenicity. Upon returning, he injected some of his chickens with these old cultures and noticed that they got sick, but did not die and he assumed that it was due to the devitalization of the culture. He tried to repeat this experiment but with a new culture that injecting the chickens would kill them, however his supply of chickens was limited and he had to use the same chickens. When he injected them, they were protected against disease, and he discovered that aging attenuated the strain and that it could be used to confer protection against disease. He named the attenuated strain vaccina (from the Latin vacca meaning cow) in honor of Jenner's work. This work marked the beginning of immunology.

Pasteur discovered that it was possible to attenuate or weaken pathogens that confer resistance and this was demonstrated with another experiment in the village of Pouilly-le-Fort in 1881. Pasteur vaccinated sheep with the anthrax bacillus (Bacillus anthracis) dimmed with heat. In this experiment, only the vaccinated sheep lived. In 1885, Pasteur vaccinated a human for the first time, Joseph Meister, a child who had been bitten by a mad dog. Pasteur administered attenuated rabies viruses, which prevented the progression of the disease. Joseph grew up and became the custodian of the Pasteur Institute. Pasteur demonstrated that vaccination worked but did not know why.

Humoral and cellular immunity

The decades that followed were exciting. The investigations of Emil von Behring and Shibasaburo Kitasato won the Nobel Prize in 1901. In 1890 they discovered that the serum of immunized animals (against diphtheria and tetanus) contained substances that could neutralize these infections. They showed that serum from animals previously immunized against diphtheria could transfer the immune state to non-immunized animals.

In 1898 Jules Bordet discovered the complement system and demonstrated that its joint action with antibodies helped destroy bacteria. So the dominant knowledge was of the so-called humoral immunity: soluble molecules in the humors of the organism.

Different scientists proved during the following decade that an active component of the immune serum could neutralize and precipitate toxins and agglutinate bacteria. This active component received names such as antitoxin, precipitin and agglutinin until in 1930 Elvin Kabat demonstrated that the gamma serum fraction (immunoglobulins) was the one that generated all these activities. The active molecules of this fraction were called antibodies.

The contributions of other giants such as Koch, Metchnikoff, Ehrlich, Rickets and the young Landsteiner, influenced by the discoveries of antibodies, complement, serological diagnosis and anaphylaxis, were very relevant to the development of this new science of immunology. In Elie Metchnikoff was the first to suggest that some cells could play an important role in the body's defense against infectious agents, due to their phagocytic capacity: macrophages. These findings open a new stage, where the cell theory questioned the humoral theory.

Classical immunology

Classical immunology is included within the fields of epidemiology. Study the relationship between body systems, pathogens and immunity. The oldest writing that mentions immunity is considered to be the one referring to the plague of Athens in 430 BC. C. Thucydides noted that people who had recovered from a previous bout of the disease could care for the sick without contracting the disease a second time. Many other ancient societies have references to this phenomenon, but it wasn't until the 19th and 20th centuries that the concept was brought into scientific theory.

The study of the cellular and molecular components that comprise the immune system, including their functions and interactions, is the central theme of immunology. The immune system has been divided into a more primitive innate immune system, and an adaptive or acquired immune system of vertebrates; the latter in turn is divided into its humoral and cellular components.

The humoral response initially refers to antibodies (soluble in humors), although it currently includes all those soluble molecules that are fundamental elements of the immune response (complement, cytokines, antimicrobial peptides, etc.). Regarding immunoglobulins, it is defined as the interaction between antibodies and antigens. Antibodies are specific proteins released from a certain class of immune cells (B lymphocytes). Antigens are defined as elements capable of initiating an immune response and becoming its target by generating specific antibodies. Immunology tries to understand the properties of these two biological entities. However, equally important is the cellular response, which can not only kill infected cells, but is also crucial in controlling the antibody response. It is then observed that both systems (humoral and cellular) are highly interdependent.

In the 21st century, immunology is expanding its horizons with research carried out in other, more specialized niches. This includes immune function of cells, organs, and systems not normally associated with the immune system, as well as immune system function outside of classical models of immunity.

Clinical Immunology

Clinical immunology is the study of diseases caused by disorders of the immune system (failure, abnormal action, and malignant growth of the cellular elements of the system). It also involves diseases of other systems, where immune reactions play a role in clinical and pathological features.

Diseases caused by disorders of the immune system fall into three broad categories:

- Immunodeficiencies, in which some element of the immune system fail to provide an adequate response (e.g. in AIDS). They may be primary (genetic or inherited) or secondary (acquired)

- Autoimmunity, in which the immune system attacks the cells of the body itself (e.g., systemic erythematous lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, (Immune Trombocytopenic Treatment), Hashimoto disease and myasthenia gravis).

- Other immune system disorders include different degrees of hypersensitivity, in which the system responds inappropriately to harmless components (asthma and other allergies) or responds with excessive intensity.

The most well-known disease that affects the immune system is AIDS, caused by HIV. AIDS is an immunodeficiency characterized by the loss of CD4+ T cells ("helper") and macrophages, which are destroyed by HIV.

Clinical immunologists also study ways to prevent transplant rejection, in which the immune system reacts to the HLA proteins of donors (when they are not fully matched).

Immunotherapy

The use of components of the immune system in the treatment of disease or disorders known as immunotherapy. Immunotherapy was born with variolation, and scientifically speaking since Edward Jenner's first vaccines.

We can talk about humoral and cellular immunotherapy. Among the humoral treatments, there is the use of Immunoglobulins in different formats: they have been used for decades in states of immunodeficiency, antisera such as anti-tetanus or anti-venoms. And more recently monoclonal antibodies. In 1984, the immunologists Jerne, Kollher and Mistein won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for discovering the in vitro manufacture of these therapeutic bullets (which have also allowed an exponential development of immunodiagnostic techniques based on the antigen-antibody reaction). These antibodies allow the treatment of patients with autoimmune or autoinflammatory pathologies, immunodeficiencies, hypersensitivities, and cancers.

This last application is undoubtedly the one that has undergone the biggest revolution in recent years. So often the concept of immunotherapy is used in the context of treating cancers along with chemotherapy (drugs) and radiotherapy (radiation). Anti-tumor immunotherapy has already been defined as the great medical revolution of the XXI century. Although many monoclonal antibodies have been developed With antitumor utility, without a doubt the CAR-T and CAR-NK type chimeric constructions are the ones that will spread most immediately.

Diagnostic immunology

The specificity of the binding between antigen and antibody has created an excellent tool in the detection of the substances in a variety of diagnostic techniques. Antibodies specific for a certain antigen can be conjugated with a radiolabel, fluorescent label, or a revealing enzyme (by color scale) and are used as tests to detect it. In a generic way, these tests are called immunoassays or immunoassays. Once the antigen-antibody complexes have been produced, these techniques reveal them:

- For their physical abilities: nephelometry (precipitation) or aglutination

- Enzymatic revealed: ELISA, Western Blot, immunohistochemistry, etc.

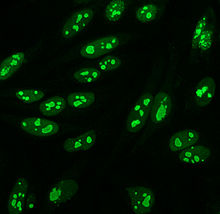

- By fluorescent development: flow cytometry, direct or indirect immunofluorescence, etc.

- Radioactive revealed: radioimmunoassay

Evolutionary immunology

The study of the immune system in extinct and living species is capable of giving us a key to understanding the evolution of species and the immune system.

A complex development of the immune system can be seen from the simple phagocytic protection of unicellular organisms, the circulation of antimicrobial peptides in insects, and the lymphoid organs in vertebrates. Of course, like many evolutionary observations, these physical properties are often viewed through the anthropocentric lens. It must be recognized that every organism alive today has an immune system quite capable of protecting it from all major forms of harm.

Insects and other arthropods, which do not possess true adaptive immunity, display highly evolved innate immunity systems, and are further protected from external damage (and exposure to pathogens) by their cuticle.

Systems immunology

Neural immunology

Branch of immunology that studies not only immunological phenomena in the brain, but also the nerve centers involved in the immune response.

Contenido relacionado

Leersia

Ebenaceae

Casuarina