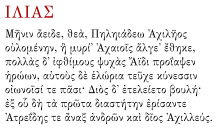

Iliad

The Iliad (Homeric Greek Ἰλιάς: Iliás; Modern Greek Ιλιάδα: Iliáda; Latin: Ilias) is a Greek epic, traditionally attributed to Homer. Composed in dactylic hexameters, it consists of 15,693 verses (divided by editors, already in antiquity, into 24 songs or rhapsodies) and its plot lies in the wrath of Achilles (μῆνις, mênis). It narrates the events that occurred during 51 days in the tenth and last year of the Trojan War. The title of the work derives from the Greek name for Troy, Ιlion.

Both the Iliad and the Odyssey were considered by the Greeks of the classical age and by later generations to be the most important compositions in Ancient Greek literature and they were used as the foundations of Greek pedagogy. Both are part of a larger series of epic poems by different authors and extensions called the Trojan cycle; however, of the other poems, only fragments have survived.

Dating and authorship

The date of its composition is controversial: the majority opinion places it in the second half of the 8th century BC. C., but there are some scholars who claim to place it in the sixth century BC. C., while others defend that there are some parts of the poem that must be much earlier, such as the catalog of ships in song II.

On the other hand, most critics believe that song X, called Dolonia, is a late interpolation, since it seems to have no connection with the rest of the poem and there are no references in this song to events narrated in the rest of the poem. Some scholars, on the other hand, defend its authenticity.

Both the Iliad and the Odyssey are generally attributed to the same poet, Homer, who is estimated to have lived in the VIII a. C., in Ionia (present-day Turkey). However, its authorship is discussed, and even the very existence of Homer, as well as the possibility that both works have been composed by the same person. These discussions date back to Greco-Roman antiquity and have continued into modern times. The 20th century has not settled that debate, but the most common dating refers to the VIII a. c.

Plot

The cholera sings, O Goddess, of the Achilles Pélida, cursed, that caused the countless pains, he rushed to Hades many brave lives of heroes and to themselves made them prey for dogs and for all birds (and thus the plan of Zeus was fulfilled) since for the first time they separated after having broken the Atrida, sovereign of men and Aquiles.

This epic poem narrates the anger of Achilles, son of King Peleus and the Nereid Thetis, its cause, its long duration, its consequences and his subsequent change of attitude. The wrath of the hairy Achilles ends along with the poem, when he reconciles with Priam, father of his enemy Hector, at which time his funeral is celebrated.

Canto I: The Plague and the Wrath

After nine years of war between the Achaeans and Trojans, a plague breaks out in the Achaean camp. Consulted the soothsayer Calcante, he predicts that the plague will not cease until Chryseis, Agamemnon's slave, is returned to her father Chryses. Achilles' anger originates from the affront inflicted on him by Agamemnon, who, by yielding to Chryseis, snatches from Achilles his part of the loot from him, the young priestess Briseis. With all this having occurred Achilles withdraws from the battle, and assures that he will only return to her when the Trojan fire reaches his own ships. He asks his mother, Thetis, to convince Zeus to help the Trojans. He accepts, since Thetis had helped him when his divine brothers rebelled against him.

Canto II: The dream of Agamemnon and Boeotia

Zeus, uneasy about his promise to Thetis, advises Agamemnon in a dream to arm his troops to attack Troy. However, Agamemnon, to test his army, proposes to the Achaeans to return to their homes but the proposal is rejected. Listed below is the catalog of the ships of the Achaean contingent and that of the Trojan forces.

Canto III: The oaths and Helena on the wall

The head of the Trojan troops, Hector, rebukes his brother Paris for hiding in the presence of Menelaus. Given this, Paris decides to challenge Menelaus in single combat. Helen, King Priam, and other Trojan nobles watch the battle from the wall, where Helen introduces some of the Achaean chiefs (teichoscopy). The battle stops for the celebration of the singular duel, with the promise that the winner would keep Helena and her treasures. Menelaus is about to kill Paris but he is saved by Aphrodite, and he is sent along with Helen.

Canto IV: Violation of oaths and review of troops

After a small assembly of the gods, they decide to resume hostilities, so Athena, disguised, incites Pandarus to break the truce by shooting an arrow that wounds Menelaus and after Agamemnon's harangue to his troops the fight resumes, in which Ares and Apollo on the one hand and Athena, Hera and other divinities, respectively help the Trojans and the Achaeans.

Canto V: Principality of Diomedes

Among the Achaeans, Diomedes stands out in battle, assisted by Athena, who is about to kill Aeneas, and wounds Aphrodite. Meanwhile, Ares and Hector command the Trojan troops and Sarpedon, leader of the Lycians, also stands out, who kills, among others, the king of Rhodes, Tlepolemus. Then, Diomedes, protected again by Athena, wounds Ares.

Canto VI: Colloquium of Hector and Andromache

Faced with the pressure of the Achaeans, Helenus, also the son of Priam and a soothsayer, urges Hector to return to Troy to commission the Trojan women to make offerings in the temple of Athena. Meanwhile, in battle, Diomedes and the Lycian Glaucus acknowledge their ties of hospitality and exchange weapons amicably. Hector, after carrying out the order of his brother Héleno from him, goes in search of Paris to rebuke him to return to battle and says goodbye to his wife Andrómache.

Canto VII: Single Combat of Hector and Ajax

After the debate between Athena and Apollo, played by Hélenus, Hector challenges any prominent Achaean to a single duel. The main Achaean chiefs, harangued by Nestor, accept the challenge and after drawing lots, Ajax Telamonio is the chosen one. The singular duel takes place but the arrival of night puts an end to the fight between the two and gifts are exchanged (gift and counter-gift). Hector hands over a sword (with which Ajax would later commit suicide) and Ajax a purple belt. Nestor urges the Achaeans to build a wall and a moat to defend their camp. The Trojans in assembly debate whether they should deliver Helena and her treasure (position defended by Antenor), or only her treasure (position defended by Paris). Priam orders that the proposal of Paris be transferred to the Achaeans. The proposal is flatly rejected, but a truce is agreed to cremate the corpses.

Canto VIII: Battle Interrupted

Zeus orders the rest of the gods to refrain from intervening in the contest. The Trojans, encouraged by Zeus, advance into battle and drive the Achaeans back. On the part of the Achaeans, Teucer causes serious damage to the Trojan ranks with his arrows. Athena and Hera try to help the Achaeans, but Iris sends an order from Zeus not to intervene. As night falls, the Trojans camp near the Achaean camp.

Canto IX: Embassy to Achilles

Phoenix, Ajax Telamonius, Odysseus and two heralds are sent as an embassy, on Nestor's advice, where they give Achilles apologies on behalf of Agamemnon (offering him gifts, the return of Briseis and any of his daughters as a wife) and beg him to return to the fight, but he refuses despite Phoenix's advice.

Canto X: Gesta de Dolón

Diomedes and Odysseus, again on Nestor's advice, carry out a night spy mission, in which they kill the Trojan Dolon, who had also been sent on a spy mission by Hector. Then, with the information obtained through Dolon, they kill Thracian soldiers and their king Reso in their sleep and take their horses.

Canto XI: Deed of Agamemnon

Dawn breaks, the battle resumes and the Achaeans start taking the initiative. Agamemnon stands out among them, until he is wounded by Coon and must retire. Then the Trojans take the initiative. The Achaeans counterattack, but Diomedes, Eurypylus, and the physician Machaon are wounded by arrows from Paris. The Trojan Soco dies at the hands of Odysseus, but manages to wound him; Patroclus is sent by Achilles to Nestor's tent for news of the battle.

Canto XII: Battle on the Wall

The Trojans, first following the advice of Polydamas, cross the moat before the Achaean wall but then ignore his advice not to assault the wall. The Lycian Sarpedon opens a breach in the wall that is crossed by the Trojan troops with Hector at the head, despite the resistance of Ajax and Teucer.

Canto XIII: Battle beside the ships

Poseidon is outraged at Zeus' favoritism toward the Trojans and takes the form of Calchas to cheer up the Achaeans. A fight breaks out in which Poseidon helps the Achaeans and Zeus the Trojans. Poseidon goes to battle to encourage the Achaeans to resist the Trojan charges. Among the Achaeans, Idomeneo, king of Crete, stands out. Helenus and Deiphobus must withdraw after being wounded by Menelaus and Meriones. But Hector continues in his advance until Ajax opposes him.

Canto XIV: Deception of Zeus

Hera conceives a plan to deceive Zeus and with the help of Aphrodite's belt she seduces Zeus and with Hypnos's she makes him sleep. She then orders Poseidon to intervene on behalf of the Achaeans. Ajax Telamonio seriously wounds Hector, who is withdrawn from combat by his companions and taken near the city. Despite the resistance of Polydamas and his brother Acamante, the Achaeans take a brief initiative in the battle.

Canto XV: New offensive from the ships

Zeus discovers the deception of which he has been the object and orders Poseidon through Iris to stop helping the Achaeans. He then urges Apollo to reinvigorate the Trojans. Ares intends to go to fight on the side of the Achaeans to avenge the death of his son Ascalaphus, but Athena warns him that he will be the object of Zeus' wrath. Hector recovers his strength and the Trojans come fighting to the ships of the Achaeans. Even Ajax Telamonius has to back off.

Canto XVI: Deed of Patroclus

Hector manages to set fire to one of the Achaean ships. Patroclus asks Achilles for permission to take his weapons and repel the attack and, commanded by the Myrmidons, makes the Trojans flee, who believe that it is actually Achilles. He kills, among others, Sarpedon, king of Lycia and son of Zeus. But Apollo comes to the aid of the Trojans and hits Patroclus, who is later wounded by Euphorbus and finished off by Hector.

Canto XVII: Deed of Menelaus

Menelaus manages to kill Euphorbus and defends the lifeless body of Patroclus, around which a tough fight ensues. The Trojans drive him back and Hector strips Patroclus of his arms. Then Achaean reinforcements come to the fight and manage to take his body to the ships.

Canto XVIII: Manufacture of weapons

Antíloco gives Achilles the news of the death of Patroclus, at the hands of Hector and he decides to return to the fight to avenge his death. Night falls and the Trojans gather. Polydamas is in favor of going to Troy and taking refuge behind its walls, but Hector's opinion of continuing to fight in the open field prevails. The goddess Thetis gets Hephaestus to make new weapons for her son Achilles.

Canto XIX: Achilles lays down his anger

Achilles reconciles with Agamemnon, who returns Briseis to him along with various gifts, as well as taking an oath that he was never with Briseis as is the custom between men and women.

Canto XX: Combat of the Gods

Zeus gives permission to the rest of the gods to intervene in the battle and help whomever they prefer. Achilles launches a furious attack in which he fights Aeneas, who is saved by Poseidon so as not to anger Zeus. He kills Polydorus, son of Priam, and Hector confronts him, but Athena helps Achilles and Apollo leads Hector away from the fight.

Canto XXI: Battle by the River

Achilles kills, among others, Lycaon, son of Priam, and Asteropeus, who manages to slightly wound him. The river god, Scamander, surrounds him with his waters and is about to drown him, but Hera goes to her son Hephaestus to drive away the river waters with the flames. The rest of the gods fight among themselves, some in favor of the Achaeans and others in favor of the Trojans. King Priam orders the gates of Troy to be opened so that his troops can take refuge behind his walls. Apollo manages, through a ruse, to momentarily move Achilles away from the walls of Troy.

Canto XXII: Death of Hector

The Trojan forces take refuge in the city, but Hector is left outside, ready to fight Achilles. Once the two warriors are face to face, Hector flees and circles the city several times. But then Athena appears and poses as Deiphobo, thus tricking Hector. This, believing that it will be a battle of two against one, finally comes face to face with Achilles, who kills him, ties his corpse to his chariot and returns to his camp on it.

Canto XXIII: Games in honor of Patroclus

The funeral games are held in honor of Patroclus with the following tests: chariot race, boxing, wrestling, running, combat, shot put, archery and javelin throw.

Canto XXIV: Rescue of Hector's corpse

Priam and an old herald head towards the Achaean camp: on the way they meet Hermes (sent by Zeus), who helps them to slip unnoticed to Achilles' tent. Priam begs Achilles to hand over Hector's corpse and offers gifts, which Achilles, moved, accepts. Then Priam asks Achilles for a bed so that he can sleep, and the son of Peleus orders two beds to be made; one for Priam and one for his herald. After that, Achilles gives, at the request of the aged Priam, eleven days for Hector's funeral, so that on the twelfth day the Trojans would fight again.

Style

Analyses of the style of the Iliad usually highlight two main elements: the specific nature of its speech («Kunstsprache» or «poetic language»), which serves as the argumentative basis for reconstructing the so-called «poetry of oral improvisation», that, coming from the Mycenaean period, it would culminate in the Iliad and the Odyssey; as well as its mode of syntactic and semantic sequence, marked by juxtaposition, the parataxis of elements, and the autonomy of the parts. Narratological analyzes, in turn, face the task of describing the character of the narrator, who would be heterodiegetic, distanced and, as has often been said, objective, despite the many nuances that this adjective would require.

Themes

We are here

Nostos, the return, occurs seven times in the poem (2.155, 2.251, 9.413, 9.434, 9.622, 10.509, 16.82). Thematically, the concept of return is widely explored in ancient Greek literature, especially in the fate of the Atreids, Agamemnon and Ulysses. Thus, the return is impossible without having sacked Troy.

Kleos

Kleos («κλέος», «glory», «fame») is the concept of glory won in heroic battle. For most of the Greek invaders of Troy, notably Odysseus, kleos is won in a victorious nostos (homecoming). However, Achilles must choose only one of the two rewards, either nostos or kleos. In Book IX (IX.410–16), he tells him so moving message to Agamemnon's envoys (Odysseus, Phoenix and Ajax) begging for their reinstatement in battle for having to choose between two fates (διχθαδίας κήρας, 9.411).

By giving up his nostos, he will earn the greatest reward of kleos aphthiton («κλέος ἄφθιτον", "undying fame"). In the poem, afhthiton («ἄφθιτον », «imperishable») is used another five times, each occurrence denoting an object: Agamemnon's scepter, Hebe's wheel, chariot, Poseidon's house, Zeus' throne, Hephaestus' house. The translator Lattimore renders kleos afhthiton as always immortal and as always imperishable , connoting Achilles' mortality by underscoring the greater reward from him returning to the battle of Troy.

Kleos is often given visible representation by prizes won in battle. When Agamemnon takes Briseis from Achilles, he takes away a part of the kleos that he had earned.

Achilles' shield, crafted by Hephaestus and given to him by his mother Thetis, bears an image of stars in the center. The stars evoke profound images of a single man's place, no matter how heroic, in the perspective of the entire cosmos.

Time

Similar to kleos is timê («respect» or «honor»), the concept that denotes the respect that a man accumulates throughout his life. The Greek problems begin with the dishonorable behavior of Agamemnon. Achilles' hatred of such behavior leads to the ruin of the Achaean military cause.

Anger

The initial word of the poem, μῆνιν (mēnin, accusative of μῆνις, mēnis, «anger, anger, rage, fury»), establishes the main theme of the Iliad: the "Wrath of Achilles". Angered by Agamemnon's actions, Achilles asks his mother Thetis to persuade Zeus to help the Trojans. Meanwhile, Hector leads the Trojans attacking the Greeks and killing Patroclus. Thereafter, accepting the possibility of death as a fair price for avenging Patroclus, Achilles turns his wrath away, returns to battle, and manages to kill Hector.

Fate

Fate (also called fatum, «fate» or «fate») drives most of the events of the Iliad. Once established, gods and men bear it, neither able nor willing to question it. It is unknown how fate is set, but it is told by Fates and Zeus by sending omens to seers such as Calchas. Men and their gods continually speak of heroic acceptance and cowardly evasion of their programmed fate. Fate does not determine all actions, incidents, and events, but it does determine the outcome of life; before killing him, Hector calls Patroclus a fool for cowardly avoiding his fate, attempting his defeat.

No, mortal destiny, with Leto's son, has killed me,

And of men was Euphorbos; you are only my third murderer.

And keep in your heart this other thing I tell you.

You yourself are not someone who will live long, but now

Death and powerful destiny are at your side,

to come down under the hands of the great son of Aiakos, Achilleus.

Here, Patroclus alludes to the predestined death by the hand of Hector, and the predestined death of Hector by the hand of Achilles. Each one accepts the outcome of his life, however, no one knows if the gods can alter fate. The first instance of this doubt occurs in Book XVI. Seeing Patroclus about to kill [Sarpedon], his mortal son, Zeus says:

Ah, I, who is destined for the most beloved of men, Sarpedón,

You must come down under the hands of Menoitios' son, Patroclo.

About her dilemma, Hera asks Zeus:

Your Majesty, son of Kronos, what kind of things have you spoken?

Do you want to bring back a man who is mortal, one for a long time?

condemned for his fate, for a death that sounds bad and releases him?

Do it then; but not all other gods will approve.

Deciding between losing a child or a permanent destiny, Zeus, the King of the gods, allows it. This motif is repeated when he considers Hector, whom he loves and respects. This time, it is Athena who challenges him:

Father of bright, dark-stained lightning, what did you say?

Do you want to bring back a man who is mortal, one for a long time?

condemned for his fate, for a death that sounds bad and releases him?

Do it then; but not all other gods will approve.

Again, Zeus appears to be able to alter fate, but fails to do so, deciding instead to abide by stated outcomes; however, on the contrary, fate spares Aeneas, after Apollo convinces the superimposed Trojan to fight Achilles. Poseidon speaks cautiously:

But come, let us keep him away from death, for fear

the son of Kronos can be angry if now Achilleus

kill this man He's meant to be the survivor,

that the generation of Dardanos will not die...

With divine help, Aeneas escapes Achilles' wrath and survives the Trojan War. Whether or not the gods can alter fate, they put up with him, even though he contradicts their human loyalties. Thus, the mysterious origin of fate is a power beyond the gods. Fate implies the primitive tripartite division of the world that Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades effected by deposing their father, Cronus, for his dominion. Zeus took the Air and the Sky, Poseidon the waters and Hades the Underworld, the land of the dead, but they share the domain of the Earth. Despite the earthly powers of the Olympian gods, only the Three Fates set the fate of Man.

Text transmission

Papyruses with copies of the Iliad from the 2nd century BC have been preserved. C., although there is evidence of the existence of one prior to the year 520 a. C., which was used in Athens to recite it at parties in honor of Athena (the so-called Panatheneas).

Already in classical antiquity this poem was considered a true story and its characters as a model of behavior and heroism to imitate. His study and the memorization of extensive episodes was common practice.

Subsequently, its transmission became widespread, especially in Europe (from the 13th century) and in Byzantium (9th to 15th centuries).

Translations

The Iliad was translated into Spanish verse by Juan de Lebrija Cano, the maestro Francisco Sánchez de las Brozas, Cristóbal de Mesa, Father Manuel Aponte, Miguel José Moreno, Francisco Estrada y Campos and an anonymous person. There is a Spanish prose translation in the British Museum of the first five songs of the Iliad, but it is not direct, but from the Latin version by Pedro Cándido Decinibre. All these translations are handwritten and many of them are lost or whose location is unknown, such as that of Manuel Aponte. In Spanish the Odyssey had better luck in print than the Iliad, since the first (printed) translation of the Iliad in Spanish dates back to dated as late as 1788 and was produced by the neoclassical writer and playwright Ignacio García Malo (Madrid: Imprenta de Pantaleón Aznar, 1788); the second was in hendecasyllables by the preceptist José Gómez Hermosilla (Madrid: Imprenta Real, 1831). Among those of the XX century, if we leave aside the incomplete and free work of Alfonso Reyes Ochoa, we can highlight the faithful and rigorous Luis Segalá (Barcelona, 1908; revised in Complete Works in Barcelona: Montaner and Simón, 1927), widely reprinted; that of Alejandro Bon, in prose (Barcelona: Ediciones Populares Iberia, 1932); the José María Aguado (Madrid, 1935), which imitates the medieval Castilian epic in eight-syllable verse and assonance rhyme (romance); the most recent by Daniel Ruiz Bueno (Madrid, Hernando, 1956) in rhythmic prose; Fernando Gutiérrez, in Castilian hexameters (Barcelona, José Janés, 1953); Francisco Sanz Franco (Barcelona: Ediciones Avesta, 1971); Antonio López Eire (1989); Agustín García Calvo (Zamora: Lucina, 1st ed. 1995 2nd corrected 2003), in assonanced hexameters that try to recreate the original style; the rhythmic version by Rubén Bonifaz Nuño (Mexico: UNAM, 1996); and that of Emilio Crespo (Madrid: Gredos Basic Library, 2000). In the XXI century, the translation by Óscar Martínez García was published (Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2010).

Cultural impact of the Iliad

The repercussion of the Iliad in Western culture is enormous and has been reflected through adaptations and versions in prose, verse, theater, film, television, and comics.

Cinema and television

- Helena de Troya (Helen of Troy). United States-Italy, 1956. Director: Robert Wise. Performers: Jacques Sernas, Rossana Podestà, Niall McGinnis, Robert Douglas, Stanley Baker, Torin Thatcher. Collect the episode of Briseida, the farewell of Hector and Andromaca and the death of this.

- The wrath of Achilles (L'ira di Achille / Fury of Achilles). Italy, 1962. Director: Marino Girolami. Performers: Gordon Mitchell, Jacques Bergerac, Cristina Gaioni, Gloria Milland, Piero Lulli, Roberto Risso.

- Troy (Troy). United States, 2004. Director: Wolfgang Petersen. Performers: Brad Pitt, Eric Bana, Orlando Bloom, Diane Kruger, Brian Cox, Peter O'Toole.

Contenido relacionado

Anacreon

Jorge Manach

National Literature Prize