Ildefonso Cerdá

Ildefonso Cerdá Suñer, in Catalan Ildefons Cerdà i Sunyer, (Centellas, December 23, 1815 – Las Caldas del Besaya, August 21, 1876), was a Spanish engineer, urban planner, lawyer, economist and politician. A multifaceted man, he wrote the General Theory of Urbanization, a pioneering work in the field, for which he is considered one of the founders of modern urbanism. His most important project was the urban reform of Barcelona of the XIX century through the Cerdá Plan, with which he created the current Ensanche neighborhood. Cerdá was not a winner; Meticulously concentrating on his work, he had family problems, his expansion project was never well received by the local estates and he ended up ruined, because the Spanish State and the Barcelona City Council did not pay him the fees they owed him. It took a century for his legacy to be recognized.

Biography

He was born in Mas Cerdá de la Garga, a property that his family had owned since the XIV century, in Centellas, Osona, Barcelona. He was the fourth son –third of the boys– of six siblings, in a family with documented roots in the Plana de Vich since 1440. Despite their rural ancestry, the Cerdás were people of the world with interests linked to American trade, a fact that undoubtedly stimulated the open spirit, concerns and faith in the progress of the young Ildefonso.

Assigned by his father to an ecclesiastical career, he studied Latin and philosophy at the seminary in Vich, the city where his family, with a liberal tradition, took refuge during the War of the Wronged in 1827. After confronting his father to Changing his professional orientation, in 1832 he moved to Barcelona, where he began studying architecture, mathematics, navigation and drawing at the Llotja School. He did not obtain the title of architect and, in September 1835, he moved to Madrid to study at the School of Engineers of Roads, Canals and Ports, where he obtained the title of engineer in 1841, after many financial hardships due to the lack of of family support.

On June 20, 1848, he married the painter Clotilde Bosch Calmell, daughter of the banker Josep Bosch Mustich, with whom he had four daughters: Pepita (1849), Sol (1850), Rosita (1851) and Clotilde (1862), the latter being a well-known harp instrumentalist. The marriage relationship did not work out well and Clotilde, the youngest daughter, was the result of his wife's adulterous relationships, although Cerdá recognized her as his own. Finally, in 1862 the marriage separated.

With the premature death of his father (1787-1844) and his two brothers, Ramon (1808-1837) and Josep (1806-1848), he inherited an important patrimony that allowed him to resign, in 1849, his official position in Obras Public, redirect his profession, enter politics and dedicate, as he himself described, «my entire fortune, all my credit, all my time, all my comforts, all my affections, and even my personal consideration in society, to the urbanizing idea”.

In the last days of his life, sick and semi-ruined, since the government owed him the fees for many of the works he carried out, he moved to the Las Caldas de Besaya spa, in Cantabria, where he died on August 21, 1876 On August 23, the newspaper La Imprenta published an obituary note with the following words: «Mr. Cerdá was liberal and had talent, two circumstances that in Spain harm and tend to create many enemies..."

In May 1970, and coinciding with the reprinting of his General theory of urbanization, after efforts by the Official College of Architects of Catalonia and the Balearic Islands, his mortal remains were transferred and buried in the Cemetery Nuevo de Montjuïc in Barcelona, carrying out various acts of homage.

Political life

Interested in the study of urbanism, in Barcelona he came into contact with the doctrines of utopian socialism by Étienne Cabet and the utopian world of his Voyage en Icarie (1840) and related to Narciso Monturiol and Ramón Martí Alsina.

After finishing his studies, he enlisted in the national militia formed by defenders of liberal ideals, where he reached the rank of lieutenant of grenadiers. His progressive ideology led him to actively participate in public life: he became a deputy for Barcelona in the Spanish Parliament in the 1850 elections –the legislature began on May 18, 1851–, forming part of a progressive candidacy along with Estanislao Figueras, Pascual Madoz and Jacinto Felix Domenech.

During the Progressive Biennium he was appointed commander of the sapper battalion of the national militia. After this period, in 1854 he became a councilor in the Barcelona City Council.

It was in the 1850s that he became more socially conscious and laid the foundations for his future urban project, seeing how the city, pressured and suffocated by the walls that surrounded it, could not grow physically or hygienically. Sensitized with the living conditions of the city and the problems of the working classes, he led the mobilization that entered the Casa de la Ciudad de Barcelona on July 3, 1855 to recover the flag that had been taken from the Workers' Associations that were generating strong social instability. This action generated enmities in the ruling classes, but it was the reason why he accompanied a delegation of Barcelona workers to Madrid to expose the problems of worker associations with Manuel Alonso Martínez, Minister of Public Works in the government of Baldomero Espartero. The following year, 1856, he was dismissed from the Barcelona City Council by Captain General Juan Zapatero y Navas and was imprisoned twice. Between 1864 and 1866 he was again a councilor in the Barcelona City Council.

The revolution of 1868 brought him back into public life and he joined the Federal Democratic Republican Party. Militant of the moderate sector of federalism, he was elected deputy by popular suffrage in the elections of 1871 for the electoral district of Centellas, of the judicial district of Vich, and in the session of constitution of the Corporation he was appointed vice-president of the Diputación de Barcelona, from where he contributed to proclaim the First Spanish Republic in 1873.

In May 1873, President Benito Arabio resigned, which is why Cerdá became President of the Provincial Council until January 1874, the date on which the Captain General of Catalonia dissolved the Corporation as a consequence of the coup d'état of General Manuel Pavia. In this period there was a Carlist outbreak and the "Junta de Salvación y Defensa de Catalunya" organized a citizen militia of men between 20 and 40 years of age. The government of Madrid did not give its approval but, despite this, four battalions of "Guías de la Diputación" were organized.

Cerdá was part of the Board of Works of the Port of Barcelona and took part in the proclamation of the federalist and republican Catalan State in 1873.

Professional career

He began his professional life as a state engineer at the head of Public Works and, between 1839 and 1849, he was assigned to Murcia, Teruel, Tarragona, Valencia, Girona and Barcelona, where he participated in the works of the first Spanish railway, the line Barcelona-Mataró. This work made him interested in the applications of the steam engine in the new and revolutionary system of locomotion represented by the railway.

He carried out statistical studies and graphic synthesis with housing proposals for various social categories and with different degrees of complexity, from the isolated house to the collective one.

Cerdá's legal proposals for the cities of Madrid and Barcelona led to new legislation, but it was found lacking in precedents, both by state and foreign legislation. In Cuatro palabras sobre el Ensanche (1861) he extensively developed the compensation system and the reparcelling technique as a means to achieve a fair distribution of the benefits and expenses of urban planning among the owners and obtaining of land in proportion and buildable in proportion to the plot contributed, a system later included in the Bill of Posada Herrera and incorporated a century later into the Soil Law of 1956.

On the economic side, Cerdá established the rules for infrastructure, division of property and attribution of plots of land in the new Barcelona.

In the field of social sciences, he tried to solve the problems of demographic concentration in cities and industrial development in his work General theory of urbanization. In this treatise he put forward theories that to a large extent he had previously applied in the Interior Reform and Expansion Project of Barcelona . He also included an assessment of the living conditions of the popular classes, with an approach to the study of social inequalities in health, where he compared the differences in life expectancy according to social class. Ildefonso Cerdá developed an authentic sociological study as an appendix to his General Theory of Urbanization since he considered the workers as his project to expand Barcelona, and only bequeathed figures for posterity, leaving behind the wishes of the working mass, which he had to gather in his social quests. According to his figures, the number of workers that existed in Barcelona at that time can be counted: of the 54,000 workers, some 6,500 could be considered "distinguished", that is, they could dress and educate themselves well. The others were simple laborers. Cerdá mentioned that there were 269 days of wages in Barcelona annually, and that the average daily salary of the worker was 8.55 reais. Only the most skilled, generally married, exceeded these salary figures. Comparing the income and expenses, only a laborer working in a textile factory, as a first or second category weaver, could meet the expenses of his marriage. But as soon as the children arrived, the deficit threatened, and with it the worries and concerns. Unforeseen illness or accident meant forced unemployment and loss of family income.

The Cerdá Plan

The most important and internationally recognized work is his expansion plan for the city of Barcelona. Born in the midst of controversy over its imposition by the Spanish government against the will of the municipal council, it was approved in June 1859 and began to be developed a year later.

Cerdá's new language

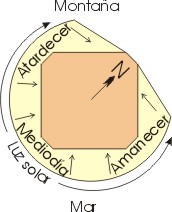

The plan provided the primary classification of the territory: the «vias» and the «intervías» spaces. The former constitute the public space for mobility, meeting, support for service networks (water, sanitation, gas...), trees (more than 100,000 trees on the street), street lighting and furniture. The "intervías" (island, block, block) are the spaces of private life, where the multi-family buildings meet in two rows around an interior patio through which all the dwellings (without exception) receive natural light from the Sun, ventilation and the joy of living, as the hygienist movements called for.

Cerdá defended the balance between urban values and rural advantages: «Ruralize what is urban, urbanize what is rural» is the message found at the beginning of his General theory of urbanization.

Structure of the Cerdá Plan

The plan proposed by Cerdà for the city highlighted an optimistic and unlimited growth forecast, the programmed absence of a privileged center, its mathematical, geometric character and a scientific vision. Obsessed by the hygienist aspects that he had studied so much, its structure makes the most of the direction of the winds to facilitate oxygenation and cleaning of the atmosphere.

In addition to hygienist aspects, Cerdá was concerned about mobility. He defined an absolutely unusual width of streets, partly to escape the inhuman density in which the city lived, but also thinking of a motorized future, with its own spaces separated from those of social coexistence, which he reserved for interior areas.

He incorporated the layout of the railway lines that had so influenced his vision of the future when he visited France, although he was aware that they had to be underground, and he ensured that each neighborhood had an area dedicated to public buildings.

The most outstanding formal solution of the project was the incorporation of the block of houses; its crucial and absolutely unique shape compared to other European cities is marked by its 113-meter square structure with 45º chamfers.

Geometry of the Ensanche

Cerdá's grid included streets 20, 30 and 60 meters wide. The blocks had buildings on only two of their four sides, giving a density of 800,000 people. With the original design, the extension would have been fully occupied around 1900, although both Cerdá himself and, later, some speculative actions substantially densified it.

Cerdá proposed the «Ensanche unlimited», a regular and imperturbable grid along the entire urban layout. Unlike other proposals that broke their repetitive rhythm to include green spaces or services, Cerdá's proposal includes them internally, which allows him to set a continuous repetition in the plan with the ability to alter it when appropriate.

The engineer's vision was of growth and modernity; his genius makes him anticipate future urban traffic conflicts, 30 years before the automobile was invented.

Cerdá unfolds the layout on the backbone of the Gran Vía. He works with modules of 10 x 10 blocks (which Cerdá considers a district) and that correspond to the main crossroads (Plaza de las Glorias Catalanas; Plaza de Tetuán; University Square), with a wider street every five (Calle de la Marina; Via Layetana, which would cross the old city 50 years later; Calle de Urgell). With these proportions, as well as the one resulting from the size of the block, Cerdá manages to locate one of the wide streets that go down from the sea to the mountain on each side of the old city (Urgell street and Paseo de San Juan) with 15 blocks. in the middle.

Exceptions to regularity

Special mention should be made of the design of Paseo de Gracia and Rambla de Cataluña where, in order to respect the old Camino de Gracia and the natural slope of the waters –hence the name of Rambla–, he drew only two consecutive lanes of special width when in reality, based on the grid of 113 m, there should be three lanes. In addition, Paseo de Gracia, in order to respect the old layout, is not exactly parallel to the rest of the streets, which is why the existing blocks between the two mentioned roads, although they are orthogonal in design with chamfers, present irregularities that make them they form a trapezoid.

To all this we must add the presence of some roads of a special nature that do not follow the reticular layout but cross it diagonally, such as Diagonal, Meridiana or Paralelo avenues, and others that were laid out respecting the existence of old communication routes with neighboring towns.

Opposition to the Cerdá Plan and contempt for the author

Before its approval, it had municipal opposition. The dominant group in Barcelona acted against the plan in the same way that they did against the growing popular protests. The anti-authoritarian, anti-hierarchical, egalitarian and rationalist character of the plan collided with the vision of the bourgeoisie, who preferred Paris or Washington as a reference for a new city, with a more particularist architecture.

The figure of Cerdá also generated antipathy among architects, since they could not forgive the affront that had meant assigning urban responsibility to an engineer. Cerdá suffered a personal smear campaign full of legends and lies. It didn't help that he came from a Catalan family from the XV century, nor that he had proclaimed the Catalan federal republic from the balcony of the Generalitat, because it ended up spreading that "he was not Catalan".

He was also despised institutionally. The expansion contest set the award of the name of the winner to a main street of the network. Cerdá was denied this award until the 1960s when the Cerdá square took its name. It is a square located outside the plot that he himself made, with an urban marginality maintained until recently and remembered for the constant problems of flooding due to poor sewage design, curiously one of the main concerns of Ildefonso Cerdá. In the same way, he was denied a monument that had already been designed in 1889 by Pere Falqués and that the mayor Francesc Rius did not want to carry out.

Main works

- 1859 - Theory of the construction of the cities, vol. 1. Barcelona, 1859. Edited in 1991 by the Ministry of Public Administrations, the City of Barcelona and the City of Madrid. ISBN 84-7088-583-9.

- 1861 - Theory of the construction of the cities, vol. 2. Madrid, 1861. Edited in 1991 by the Ministry of Public Administrations, the City of Barcelona and the City of Madrid. ISBN 84-7088-586-3.

- 1863 - Theory of the liaison of the movement of the marine and terrestrial routes.

- 1867 - General theory of urbanization and application of its principles and doctrines to the reform and ensanche of Barcelona. Madrid: Spanish Printer, 1867. Reissued by the Institute of Fiscal Studies, 1968-1971.

- 1867 - Statistical monograph of the working class Barcelona, in 1856: A specimen of a functional statistics of urban life, with concrete application in that class. It was published as an appendix to the General theory of urbanization.

- - General theory of ruralization.

Personal background

The personal and cartographic documentation of Ildefonso Cerdá, preserved in the Historical Archive of the City of Barcelona (AHCB), comes from the donation that the College of Civil Engineers, Canals and Ports of Catalonia made to Barcelona City Council, on 27 September 1979.

The cartographic collection of the Cerdá Legacy, deposited in the Graphics section of the AHCB, is an irreplaceable source for deepening the systematic knowledge of some of the characteristics of the Llano de Barcelona territory. It consists of a set of 56 original large-format plans that cover the territory to be developed and that provide detailed information on the space located between the walled enclosure of Barcelona, the Montjuic mountain and the suburban areas of El Llano.

The series of personal documentation is made up of a total of 32 texts, fourteen autobiographical and eighteen urbanistic. This documentation covers a chronological period that extends between 1841 and 1876.

Contenido relacionado

Juana I of Castile

French Revolution

Hermeric