Il Canto degli Italiani

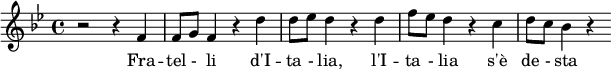

Il Canto degli Italiani (in English, "The Song of the Italians") is a song from the time of Italian unification written by Goffredo Mameli and composed by Michele Novaro in 1847, which is also the national anthem of the Italian Republic. It is also known as the Inno di Mameli ("Mameli's Hymn"), for the author of the lyrics, or as Fratelli d'Italia ("Brothers of Italy") for its first verse. The lyrics consist of six verses and a chorus that is repeated at the end of each verse, and is set to music in 4/4 time in the key of B flat major. The sixth verse takes up the text of the first with some variations.

It was very popular during the unification of Italy and in the following decades, although after the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy (1861) the Marcia Reale ("Royal March") was chosen as the anthem of the kingdom, which was the official anthem of the House of Savoy. The Canto degli Italiani was considered too little conservative for the political situation of the time, since it was characterized by a strong republican and Jacobin imprint, which did not correspond to the epilogue of Italian unification, which was of a monarchical nature.

After World War II, Italy became a republic and the Canto degli Italiani was chosen, on October 12, 1946, as the provisional national anthem, a role it maintained even afterwards, becoming in the de facto anthem of the Italian Republic. In the following decades various parliamentary initiatives were carried out to make it the official national anthem, until the law n.º 181 of December 4, 2017 awarded the Canto degli Italiani the category of national anthem de iure.

History

Origin

The lyrics of the Canto degli Italiani were written by the Genoese Goffredo Mameli, then a young student and fervent patriot, in a historical context characterized by a generalized patriotism that already presaged the revolutions of 1848 and the first Italian War of Independence. According to the thesis of the historian Aldo Alessandro Mola, the author of the lyrics of the Canto degli Italiani would actually be Atanasio Canata. However, this hypothesis is rejected by most historians. On the exact date of the letter's writing, sources differ. According to some authors, the hymn was written by Mameli on September 10, 1847, while according to others the composition's date of birth was two days earlier, on September 8.

After rejecting the idea of adapting it to existing music, on November 10, 1847, Goffredo Mameli sent the lyrics of the hymn to Turin to be set to music by the Genoese composer Michele Novaro, who was at the time in the house of the patriot Lorenzo Valerio. Novaro was captivated by the idea and, on November 24, 1847, he decided to set it to music.

Mameli, who was a republican, Jacobin, and supporter of the motto born of the French Revolution Liberté, égalité, fraternité ("Liberty, equality, fraternity"), was inspired by the hymn French national, La Marseillaise, to write the lyrics of the Canto degli Italiani. For example, the verse Stringiamci a coorte ») is reminiscent of the line from the French anthem Formez vos bataillon ("Form your battalions").

The Greek national anthem, composed in 1823, was another piece that inspired Mameli to write her anthem. Both compositions contain references to classical antiquity, which is seen as an example to follow to free oneself from foreign domination, and call for combativeness, necessary to aspire to regain freedom. In the Greek hymn there is present, as in the Canto degli Italiani, a mention of the Austrian Empire and its rule over the Italian peninsula. A verse from the complete version of the anthem of Greece, which is made up of 158 stanzas, reads "The eagle's eye nourishes wings and talons with the entrails of the Italian", where the eagle is the Austrian imperial shield.

Italy is also mentioned in the Polish national anthem, written in 1797 in Reggio Emilia during the Napoleonic era, whose refrain reads Marsz, marsz, Dąbrowski, z ziemi włoskiej do Polski ("March, march, Dąbrowski, from Italian soil to Poland"). The lyrics refer to the recruitment, among the ranks of the Napoleonic armies stationed in Italy, of Polish volunteers who had fled their homeland because they were persecuted for political reasons. Poland, in fact, was shaken by uprisings aimed at independence from Austria and Russia. These volunteers participated in the first Italian campaign with the promise, from Napoleon, of an incipient war of liberation for Poland. In particular, the lyrics urge the Polish general Jan Henryk Dąbrowski to return with his armies to his land as soon as possible. The reference is reciprocal, since the fifth verse of the Canto degli Italiani mentions the political situation in Poland, which at that time was similar to the Italian one, since both peoples were subject to foreign domination. This reciprocal quote between Italy and Poland in their respective anthems is unique in the world.

In the original version of the anthem, the first verse of the first stanza read Evviva l'Italia ("Long Live Italy"), but Mameli changed it to Fratelli d'Italia ("Brothers of Italy") almost certainly at the suggestion of Michele Novaro himself. The latter, when he received the manuscript, also added a resounding Sì! ("Yes! ») at the end of the chorus sung after the last verse.

Debut

The hymn made its public debut on December 10, 1847 in Genoa when, in the square of the sanctuary of Our Lady of Loreto in the Oregina neighborhood, it was presented to the citizens on the occasion of a commemoration of the revolt in the neighborhood Genoese of Portoria against the occupiers of Austria during the war of the Austrian succession. On the occasion it was performed by the Filarmonica Sestrese, then the municipal band of Sestri Ponente, in front of a part of those 30,000 patriots —from all over Italy— who had gathered in Genoa for the commemoration.

As its author was a famous follower of the Genoese patriot Giuseppe Mazzini, the piece was banned by the Savoyard police until March 1848. Its musical performance was also banned by the Austrian police, who also prosecuted its sung performance —considered a criminal offense political—until the end of World War I.

There are two surviving autographed manuscripts. The first, the original linked to the first draft, is in the Mazziniano Institute in Genoa, while the second, the one sent by Mameli on November 10, 1847 to Novaro, is kept in the Museo del Risorgimento in Turin. The autographed manuscript that Novaro sent to the publisher Francesco Lucca is instead in Milan, in the Ricordi Historical Archive.

The first criticisms of the Canto degli Italiani were made by Giuseppe Mazzini, who considered the music unmartial. The Genoese patriot also contested the lyrics, and commissioned a new composition from Mameli in 1848, set to music by Giuseppe Verdi, whose title was Suona la tromba ("The trumpet sounds"). However, even this new song did not find favor with Mazzini, so it was the Canto degli Italiani that became the hymn symbol of Italian unification, a process known in Italy as Risorgimento ("Resurgence").

From the revolutions of 1848 to the Expedition of the Thousand

When the Canto degli Italiani made its debut, the revolutions of 1848 were only a few months away. Shortly before the promulgation of the Albertine Statute, a compulsory law had been repealed that prohibited gatherings of more than ten From this moment on, the Canto degli Italiani experienced increasing success also thanks to its catchiness, which facilitated its diffusion among the population.

Over time, the hymn became more and more popular and was sung at almost all events, which is why it became one of the symbols of the Risorgimento. In fact, the composition It was sung on several occasions by the insurgents on the occasion of the five days of Milan, and was sung frequently during the celebrations of the promulgation, by Carlos Alberto de Sardeña, of the Albertine Statute. Even the brief experience of the Roman Republic (1849) had, among the hymns most sung by the volunteers, the Canto degli Italiani , with Giuseppe Garibaldi who used to hum and whistle it during the defense of Rome and the flight to Venice.

When the song became popular, the Savoyard authorities censored the fifth verse, with very strong anti-Austrian lyrics. However, after the declaration of war on Austria and the start of the first Italian War of Independence (1848-1849), Savoy soldiers and military bands performed it so frequently that King Charles Albert was forced to remove all censorship. In fact, the anthem was widespread among the ranks of the Republican volunteers, sharing its popularity with the song Addio mia bella addio ("Farewell, my beauty, goodbye")..

The Canto degli Italiani was also one of the most popular songs of the Second Italian War of Independence (1859), this time along with La bella Gigogin and Va, pensiero ("Fly, thought") by Giuseppe Verdi. Mameli's hymn was also one of the most sung songs during the Expedition of the Thousand (1860), with which Garibaldi conquered the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, in conjunction with the Inno di Garibaldi ("Garibaldi's Hymn"). In Quarto, the two songs were often sung by Garibaldi and his troops.

From the unification of Italy to the First World War

After the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy (1861) the Marcia Reale ("Royal March"), which was composed in 1831, was chosen as the national anthem. This decision was made because the Canto degli Italiani , which had slightly conservative lyrics and was characterized by a strong republican and Jacobin imprint, did not correspond to the epilogue of Italian unification, which was monarchical in nature. While Mameli's references to republican principles were more historical than political, the song was also frowned upon in socialist and anarchist circles, who considered it too unrevolutionary.

In 1862 Giuseppe Verdi, in his Hymn of the Nations —composed for the Universal Exhibition in London—, entrusted the Canto degli Italiani, and not the Marcia Reale, the role of representing Italy, an authoritative sign of the fact that not all Italians identified in Marcia Reale the anthem that best expressed the feeling of national unity Consequently, Mameli's anthem was incorporated on this occasion along with God Save the Queen and La Marseillaise. Even the patriot and politician Giuseppe Massari, who later became one of Cavour's most important biographers, preferred the Canto degli Italiani as a representative song of national unity. The only official anthem present in Verdi's composition was God Save the Queen, since La Marseillaise, with strong republican connotations, was not yet the representative song of the French state, which at that time was not It was not a republic but a monarchy ruled by an emperor, Napoleon III.

The chant was one of the most common songs during the third Italian War of Independence (1866), after which, with the unification of Italy almost complete, the beginning of the second verse was changed from Noi siamo da secoli / calpesti, derisi ("We have been for centuries / trampled on, humiliated") to Noi fummo per secoli / calpesti, derisi ("We have been for centuries / trampled on, humiliated »), and in the chorus the phrase siam pronti alla morte ("we are prepared for death") was repeated.

Mameli's hymn was sung at the capture of Rome on September 20, 1870, where he was accompanied by choirs that sang it along with La bella Gigogin and Marcia Reale, in addition to being often performed by the military band of the Bersaglieri . Even after Italian unification, the Canto degli Italiani , which was taught in schools, it continued to be popular among Italians, but now accompanied by other musical compositions related to the political and social situation of the time such as the Inno dei lavoratori ("Hymn of the workers") and Addio a Lugano ("Farewell to Lugano"), which partly eclipsed the popularity of the songs originating from the unification era, as they had a meaning more tied to everyday problems.

The Canto degli Italiani, thanks to its references to patriotism and armed struggle, was successful again during the Italo-Turkish War (1911-1912), when it joined A Tripoli ("To Tripoli"), and in the trenches of the First World War (1915-1918), where it was a symbol for the irredentism that characterized it, despite the fact that by the end of that conflict armed, preferred in the patriotic context other musical compositions with a more military tone such as La canzone del Piave («The song of the Piave»), Canzone del Grappa («Song of the Grappa ») or La campana di San Giusto ("The Bell of Saint Justus"). Shortly after Italy entered World War I, on July 25, 1915, Arturo Toscanini performed the Canto degli Italiani during an interventionist demonstration.

In 1916 Nino Oxilia directed the silent film L'Italia s'è desta! ("Italy has awakened!"), whose title takes up the second line of the Canto degli Italiani. The screening of the film was accompanied by an orchestra with a choir that performed the most famous patriotic hymns of the time: the Inno di Garibaldi, the Canto degli Italiani, the choir from Mosè in Egitto («Moses in Egypt») by Gioachino Rossini and from Nabucco and I Lombardi alla prima crociata («The Lombards in the First Crusade") by Giuseppe Verdi.

During Fascism

After the March on Rome (1920) Fascist songs such as Giovinezza ("Youth") became important, which were widely disseminated and publicized, as well as taught in schools, although they were not hymns In this context, the use of non-fascist melodies was discouraged, and the Canto degli Italiani was no exception.

In 1932 the secretary of the National Fascist Party Achille Starace decided to ban musical pieces that did not praise Benito Mussolini and, more generally, those that were not directly linked to fascism. In this way, songs considered subversive, such as those of a socialist or anarchist style, including the Inno dei lavoratori or The Internationale, and the official anthems of foreign nations not sympathetic to fascism such as La Marseillaise. After the signing of the Lateran Pacts between the Kingdom of Italy and the Holy See (1929), anticlerical songs had already been prohibited. Despite this, the songs of the At the time of Italian unification they were tolerated, and the Canto degli Italiani, which was forbidden in official ceremonies, received a certain leniency on special occasions.

Songs such as the Nazi anthem Horst-Wessel-Lied ("Horst Wessel Song") and the Francoist song Face to the Sun were encouraged in the same spirit, since that they were official compositions of regimes similar to the one led by Mussolini. On the other hand, some songs were limited, such as La canzone del Piave, performed almost exclusively during the anniversary of the victory in World War I every November 4.

World War II

During World War II, fascist songs composed by regime musicians were the ones that were broadcast on the radio, so very few songs were born spontaneously among the population. In the years of this war, songs were common A primavera viene il bello ("In spring comes the best"), Battaglioni M ("Battalions M"), Vincere! ("¡ Vencer!») and Camerata Richard («Comrade Richard»), while, among the songs born spontaneously, the most famous was Sul ponte di Perati (« On the Perat bridge").

After the armistice of September 8, 1943, the Italian government provisionally adopted La canzone del Piave as the national anthem, replacing the Marcia Reale —the The Italian monarchy was questioned for having allowed the establishment of the fascist dictatorship. > who fought against the Republicans and Germans.

In this context, Mameli's anthem, together with other songs originating from the unification era and some partisan songs, resounded in southern Italy liberated by the Allies and in the areas controlled by the partisans to the north of the war front. The Canto degli Italiani, in particular, found good success in anti-fascist circles, where it was joined by Fischia il vento ("Blows the wind") and Bella ciao ("Goodbye, beautiful"). Some scholars believe that the song's success in anti-fascist circles was decisive in its selection as the provisional anthem of the Italian Republic.

The Canto degli Italiani is often mistakenly referred to as the anthem of Benito Mussolini's Italian Social Republic. However, the lack of an official hymn in this state is documented, which in ceremonies was occupied by the hymn of Mameli or Giovinezza. The Canto degli Italiani and, in general, the ideas of the unification era were used by the Mussolini Republic, in a change of ideas with respect to the past, only for propaganda purposes.

From the end of the war to its provisional adoption

In 1945, once the war was over, Arturo Toscanini conducted in London the performance of the Hymn of Nations composed by Verdi in 1862, which incorporates the Canto degli Italiani. As a provisional official anthem, instead, after the birth of the Italian Republic, La canzone del Piave was temporarily confirmed.

For the choice of the official anthem, a debate was opened in which the main options were Va, pensiero from Verdi's Nabucco, the writing of an unpublished song, the Canto degli Italiani, the Inno di Garibaldi and the confirmation of La canzone del Piave. The political class of the time then approved the proposal of the Minister of War Cipriano Facchinetti, who provided for the adoption of the Mameli anthem as the provisional anthem of the State.

The canzone del Piave therefore had the role of national anthem of the Italian Republic until the Council of Ministers on October 12, 1946, when Cipriano Facchinetti, of Republican political conviction, officially announced official that during the oath of the Armed Forces on November 4, as a provisional anthem, the Canto degli Italiani would have been adopted.

Facchinetti also stated that a draft decree would be proposed confirming Mameli's anthem as the provisional national anthem of the newly formed republic, an intention that was not followed, however. There was no consensus on the choice of Canto degli Italiani, since, for example, from the columns of l'Unità, the newspaper of the Italian Communist Party, the Inno di Garibaldi as a national song. In fact, the Italian left considered Garibaldi as the most prominent figure of unification and not Mazzini, who was considered second class with respect to the "hero of two worlds".

The Minister of War proposed to formalize the Mameli anthem in the Constitution, which was being prepared at the time, but without success. The Constitution, which entered into force in 1948, established in its article 12 the use of the flag, but it did not establish the anthem or the emblem of the republic, which was later approved by legislative decree of May 5, 1948. The emblem was chosen after two contests in which a total of 800 logos created by 500 artists participated, where The winner was Paolo Paschetto with his well-known Stellone ("Big Star"). However, the definitive approval of the Constitution, which took place on December 22, 1947 by the Constituent Assembly, was received by the audience attending the session from the stands, and later also by the founding fathers, with a spontaneous interpretation of the Canto degli Italiani.

In some institutional acts organized abroad shortly after the proclamation of the Republic, due to the non-formalization of the Canto degli Italiani, the musical bodies of the host nations played by mistake, to the shame of the Italian authorities, the Marcia Reale. On one occasion, in an African state, the national band of the host country performed 'O sole mio ("My sun").

Mameli's anthem was at that time a great success among Italian emigrants, and indeed a large number of sheet music of the Canto degli Italiani can be found, along with Italian flags, in many stores in the various Little Italy (“Little Italy”) scattered throughout the Anglo-Saxon world. The Italian national anthem is often performed on more or less official occasions in North and South America, and, in particular, it was the soundtrack for a fundraiser for the Italian population devastated by World War II, which was organized in America.

Rediscovery

After reaching the status of provisional national anthem, the Canto degli Italiani began to be criticized, so much so that on several occasions there was talk of its replacement. In the 1950s it was decided to carry out a radio poll to establish which piece of music should replace Mameli's anthem as the Italian national anthem. In this poll, which did not decree the official change of the anthem due to its lack of success, Va, pensiero by Verdi. a more modern hymn with a higher cultural caliber, but which did not prosper due to the poor quality of the musical compositions received. In 1960 RAI, in a television program, launched a survey to choose the piece of music that should replace the Mameli's anthem as Italian national anthem; however, all the options presented were rejected by the public.

Criticism continued in the following decades, and from the Social Movements of 1968 the Canto degli Italiani was the object of collective disinterest and, very often, of true and genuine aversion. Given its references to the armed struggle and the homeland, Mameli's anthem was seen as an archaic musical composition with marked right-wing characteristics. Among the political exponents who proposed the replacement of the Canto degli Italiani were Bettino Craxi, Umberto Bossi and Rocco Buttiglione. Among the musicians who called for a new national anthem was Luciano Berio. Michele Serra suggested the revision of the modern Italian text, while Antonio Spinosa judged the Canto degli Italiani to be too macho.

It was the President of the Italian Republic, Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, in office from 1999 to 2006, who activated a work to enhance and relaunch the Canto degli Italiani as one of the symbols of Italian identity To avoid criticism, Ciampi often entrusted the interpretation of the anthem, on official occasions, to important conductors such as Zubin Mehta, Giuseppe Sinopoli, Claudio Abbado and Salvatore Accardo. A visible aspect of this promotional action consisted in persuading to the players of the Italian soccer team to sing the anthem during its performance before sporting events from the 2002 World Cup, since before this tournament it was customary for neither the soccer players nor the public to accompany the melody with their singing.

Ciampi also restored the holiday for the Feast of the Italian Republic on June 2 and its military parade in the imperial forums of Rome, in what was the execution of a more general action to enhance the national symbols of Italy. Ciampi's initiative was taken up and continued by his successor Giorgio Napolitano, with special emphasis during the celebrations of the 150th anniversary of the unification of Italy.

Ciampi's action began after his protest gesture against Riccardo Muti at the premiere of the 1999-00 season at La Scala Theatre. The president refused the traditional congratulatory visit to the director in his dressing room, since Muti had not opened the evening, as usual, with the Canto degli Italiani . The director found Mameli's hymn inappropriate, and instead presented Ludwig van Beethoven's Fidelio. with the goal of liberation from foreign domination, which the song addresses to the Italian people against the pain transmitted by the superior in musical terms Va, pensiero, the most frequent candidate for its replacement. Therefore, Muti considered the anthem, with its charge of invigorating senses of the patriotic spirit, more suitable to be performed at official events. Other musicians, such as composer Roman Vlad, consider the music to be anything but bad and not inferior to music. of many other national anthems. On the occasion of the celebrations of June 2, 2002, a correct version in the philological sense of the melody of the score was presented, the work of Maurizio Benedetti and Michele D'Andrea, which takes up the signs of expression present and in the Novaro manuscript.

Officialization

In 2005, a bill was passed in the Senate Committee on Constitutional Affairs. This project did not prosper due to the expiration of the legislature, although an erroneous communication was made in which it was reported that a decree-law dated November 17 had been approved, thanks to which the Canto degli Italiani would have obtained its official status. This incorrect information was also communicated later by authorized sources.

In 2006, with the new legislature, a bill was discussed, always in the Committee on Constitutional Affairs of the Senate, which provided for the adoption of a specification on the lyrics, music and modality of the performance of the anthem. In the same year a constitutional bill was submitted to the Senate that required the amendment of article 12 of the Italian Constitution with the addition of the paragraph "The anthem of the Republic is Fratelli d'Italia », but which did not prosper due to the early dissolution of the chambers. In 2008 other similar initiatives were adopted in parliament, but they failed to formalize the Canto degli Italiani in the Constitution, so which was still provisional and approved de facto.

On September 16, 2009, a bill was presented, which was never discussed, which provided for the addition of the paragraph «The anthem of the Republic is Il Canto degli Italiani by Goffredo Mameli, with music by Michele Novaro" to article 12 of the Constitution. In turn, on November 23, 2012, a law was approved establishing the obligation to teach the Mameli anthem and other Italian national symbols in schools. This norm also provides for the teaching of the historical context in which the musical composition was written, with special attention to the premises that motivated its birth.

On June 29, 2016, following the provision of November 23, 2012, a bill was submitted to the Constitutional Affairs Committee of the Chamber of Deputies to convert the Canto degli Italiani in the official anthem of the Italian Republic. On October 25, 2017, the Constitutional Affairs Committee of the Chamber approved this bill with the corresponding modifications and on October 27 it passed to the corresponding committee of the Senate of the Republic. On November 15, 2017, the Constitutional Affairs Committee of the Senate approved the bill that recognizes the Canto degli Italiani by Goffredo Mameli and Michele Novaro as the national anthem of the Italian Republic.

Since the two aforementioned parliamentary commissions approved the provision in the legislative seat, the latter was promulgated directly by the President of the Italian Republic on December 4, 2017 as "law no. 181" without the need for the usual passages in parliamentary halls. On December 15, 2017, the process was definitively concluded, with the publication in the Gazzetta Ufficiale of Law No. 181 of December 4, 2017, entitled «Recognition of the Canto degli Italiani by Goffredo Mameli as the national anthem of the Republic", which entered into force on December 30, 2017.

Letter

First verse

Fratelli d'Italia

L'Italia s'è desta

Dell'elmo di Scipio

S'è tape la testa

Dov'è la Vittoria?!

He's got the goose.

Ché schiava di Roma

Iddio.Brothers of Italy

Italy has woken

With the Eelmo of Escipion

He's covered his head.

Where's the Victoria?

Offer this the scalp

That slave of Rome

God created it.

The first verse of the first stanza contains a reference to the fact that Italians belong to a single people and are therefore Fratelli d'Italia ("Brothers of Italy"), which also gave rise to one of the names by which the Canto degli Italiani is known. This exhortation to Italians, understood as brothers, to fight for their country, is found in the first verse of many patriotic poems from the time of Italian unification. Su, figli d'Italia! su, in armi! coraggio! ("Come on sons of Italy! On the warpath! Courage!") is the beginning of All'armi! all'armi! ("To arms! To arms!") by Giovanni Berchet, and Fratelli, all'armi, all'armi! ("Brothers, to arms, to arms!") is the first verse of All'armi! ("To arms!") by Gabriele Rossetti, while Fratelli, sorgete ("Brothers, arise") is the beginning of Giuseppe Giusti's chorus of the same name. A Tuscan folk song, attributed to Francesco Domenico Guerrazzi and mentioning Pope Pius IX, had as its first verse Su, fratelli! D'un Uom la parola ("Up, brothers! The word of a man").

The first stanza also mentions the Roman politician and military man Publius Cornelius Scipio, who is called in the hymn Scipio, his Latin name. Scipio defeated the Carthaginian general Hannibal at the Battle of Zama (202 BC), which concluded the Second Punic War, and liberated the Italian peninsula from the Carthaginian army. After this battle, Scipio was nicknamed "the African". According to Mameli, Italy now metaphorically wears the helmet of Scipio, ready to fight to throw off the foreign yoke and reunite. The phrase l'Italia s'è desta (« Italy has awakened") was already included in the hymn of the Parthenopean Republic of 1799, which was set to music by Domenico Cimarosa, inspired by the writings of Luigi Rossi.

Always in the first stanza, the goddess Victoria is also referred to with the rhetorical question Dov'è la Vittoria? ("Where is Victory?"), who for a long time time was closely linked to Ancient Rome —Ché schiava di Roma (“That slave of Rome”)— by God’s design —Iddio la creò (“God created her »)—, but who now consecrates herself to the new Italy by giving her hair to be cut —Le porga la chioma ("Let her offer her hair")—, thus becoming a slave. These verses refer to the custom of the slaves of Ancient Rome to wear their hair short, while the free Roman women, on the other hand, wore it long. As for the "slave of Rome", the meaning is that the Ancient Rome made, with its conquests, the goddess Victoria "its slave". Now, however, the goddess is willing to "be a slave" to the new Italy in the series of wars necessary to expel the foreigner from the national soil and unify the country. With these Mameli verses, with a recurring theme of unification, alludes to the awakening of Italy from a lethargy that lasted centuries, in a renaissance inspired by the glories of Ancient Rome.

This strong reference to the history of Ancient Rome stems from the fact that this historical period was carefully studied in the schools of the time, and that, in particular, Mameli's cultural preparation had strong classical connotations. Roman republican history is also taken up in the first stanza of the composition.

Chorus

Stringiamci a coort,

siam pronti alla morte.

Siam pronti alla morte,

l'Italia chiamòLet's get together in cohort,

We are prepared for death.

We are prepared for death,

Italy called

The refrain mentions the cohort, a military unit of the Roman army that corresponds to one tenth of a legion. With Stringiamci a coorte, siam pronti alla morte, l'Italia chiamò («Let us come together in cohort, we are prepared for death, Italy called») alludes to the call to arms of the Italian people with the with the goal of expelling the foreign ruler from the national soil and unifying the country, at that time still divided into seven pre-unitary states. "Coming together in a cohort" metaphorically means closing ranks and preparing to fight. In the chorus, for metrical reasons, the syncopated term stringiamci, written without the letter “o” is present instead of stringiamoci.

The boisterous Sì! ("Yes!") added by Novaro to the refrain sung after the last verse alludes instead to the oath of the Italian people to fight to the death for the liberation of the soil national from abroad and the unification of the country.

Second verse

Noi fummo da dryli

Calpesti, derisi

Perché non siam Popolo,

Perché siam divisi

Raccolgaci un'Unica

Bandiera, a Speme

Di fonderci insieme

Già l'ora suonòWe've been for centuries.

Flatteados, humillados

Because we are not a people,

Because we're split.

Get us together.

Flag, a hope

To merge

It's time.

In the second verse, instead, reference is made to the hope that Italy, still divided into pre-unitary states and therefore for centuries often treated as a land of conquest, would be reunited under a single banner by merging into a single nation. Mameli, in the second verse, therefore underlines the reason for Italy's weakness: political divisions.

Third verse

Uniamoci, amiamoci

L'unione e l'amore

Rivelano ai Popoli

I saw him from Signore

Giuriamo far Libero

Il suolo natio

Uniti, per Dio,

Chi vincer ci può!Let's join, let's love

Union and love

Reveal the Peoples

The ways of the Lord

We swear to make free

The native soil

United, for God's sake,

Who can beat us?

The third stanza encourages the search for national unity with the help of Divine Providence and thanks to the participation of all the Italian people united with a common intention. The expression per Dio ("by God") is a Gallicism, with which Mameli refers to help from God.

These verses take up Mazzini's idea of a united and cohesive people fighting for their freedom following God's will. In fact, the mottos of Young Italy were Unione, forza e libertà ("Union, strength and freedom") and Dio e popolo ("God and people"). These verses also recognize the romantic imprint of the historical context of the time.

Fourth verse

Dall'Alpi to Sicily

Dovunque è Legnano,

Ogn'uom di Ferruccio

Ha il core, ha la mano,

I bimbi d'Italia

If you're chiaman Balilla

Il suon d'ogni squilla

I Vespri suonòFrom the Alps to Sicily

Everywhere is Legnano

Every man of Ferruccio

He's got his heart, he's got his hand.

The children of Italy

They're called Balilla.

The sound of each bell

In the Vespers sounded

The fourth verse is full of references to important events linked to the centuries-old struggle of Italians against foreign domination. By citing these examples, Mameli wants to instill courage in the Italian people by pushing them to seek revenge. This stanza begins with a reference to the Battle of Legnano – Dall'Alpi a Sicilia / dovunque è Legnano («From the Alps to Sicily / Legnano is everywhere») – which was fought on May 29, 1176 near the city of the same name. This battle saw the Lombard League victorious over the imperial army of Frederick Barbarossa, and put an end to the Teutonic emperor's attempt to hegemonize northern Italy. Legnano, thanks to the historic battle, is the only city besides Rome that is mentioned in the Italian national anthem.

In the same stanza Ferruccio is also quoted —Ogn'uom di Ferruccio / ha il core, ha la mano («Every man of Ferruccio / has the heart, has the hand»)—, or Francesco Ferrucci, the heroic leader in the service of the Republic of Florence who was defeated at the Battle of Gavinana, on August 3, 1530, by Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire during the siege of the city tuscany. Ferrucci, who was a prisoner, wounded and defenseless, was later executed by Fabrizio Maramaldo, an Italian condottiere fighting for the emperor. Before dying, Ferrucci addressed Maramaldo with contempt: Vile, tu uccidi un uomo morto! ("You vile, you kill a dead man!").

The fourth stanza also refers to Balilla —I bimbi d'Italia / si chiaman Balilla ("The children of Italy / are called Balilla")—, the young man who It originated, with the throwing of a stone at an officer, on December 5, 1746, the popular revolt of the Genoese neighborhood of Portora against the occupiers of the Habsburg Empire during the war of the Austrian succession, which led to the liberation of the Ligurian city.

The same stanza also mentions Sicilian Vespers —Il suon d'ogni squilla / i Vespri suonò ("The sound of every bell / At Vespers rang")—, the insurrection that took place in Palermo in 1282 and that began a series of clashes called the "Vespers wars", which led to the expulsion of the Angevins from Sicily. With the phrase "every bell" Mameli refers to the ringing of bells on March 30, 1282 in Palermo, which called on the people to rebel against the Angevins, a fact that started the Vespers wars. These bells were the of the vespers, that is, those of the evening prayer, hence the name of the revolt.

Fifth verse

They're giunchi che piegano

Le spade vendute

Già l'Aquila d'Austria

Le penne has perduted

Il sangue d'Italia

Il sangue Polacco

Bevé, col cosacco

Ma il cor le bruciòThey're cubits that bend

The swords sold

Already the eagle of Austria

The feathers have lost

The blood of Italy

Polish blood

He drank with the Cossack

But the heart burned him

The fifth verse is dedicated to the declining Austrian Empire. In fact, the text refers to the mercenary troops of the Habsburgs—Le spade vendute "The Sold Swords"—of which the Habsburg monarchy made extensive use. These troops, according to Mameli, Son giunchi che piegano ("They are reeds that bend"), since, fighting only for money, they are not as brave as soldiers and patriots who sacrifice themselves for their own nation. The presence of these mercenary troops, for Mameli, weakened the Austrian Empire.

The stanza also mentions the Russian Empire, called in the anthem il cosacco ("the Cossack"), which participated, along with the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia, in the partitions of Poland at the end of the 18th century. Therefore, reference is made to another people oppressed by the Austrians, the Poles, which between February and March 1846 were subjected to violent repression by Austria and Russia.

With the fifth stanza, Mameli refers to the fact that the Italian and Polish people undermine the Austrian Empire from within, as a result of suffering repressions, and due to the mercenary troops of the Austrian imperial army. The text also refers to the eagle double-headed, the imperial coat of arms of the Habsburgs. The stanza, with strong political connotations, was initially censored by the Savoy government to avoid friction with the Austrian Empire.

Sixth verse

Evviva l'Italia

Dal sonno s'è desta

Dell'elmo di Scipio

S'è tape la testa

Dov'è la Vittoria?!

He's got the goose.

Ché schiava di Roma

Iddio.Viva Italy

From the dream

With the Eelmo of Escipion

He's covered his head.

Where's the Victoria?

Offer this the scalp

That slave of Rome

God created it.

The sixth and last stanza, which is almost never performed, appeared in printed editions after 1859 together with the five stanzas defined by Mameli —who died on July 6, 1849 during the defense of the Roman Republic— in the original text of the song. This stanza joyfully heralds the unification of Italy —Evviva l'Italia, / dal sonno s'è desta ("Long live Italy / from sleep has awakened")—, and continues with the same three verses that conclude the opening verse quatrain.

Music

Novaro's musical composition is written in a typical marching time signature (4/4). In the key of B flat major. It has a catchy character and an easy melodic line that simplifies memory and interpretation. For On the other hand, at a harmonic and rhythmic level, the composition presents a greater complexity, which is evident in measure 31, with the important final modulation in the near tone of E flat major, and with the agogic variation of the initial Allegro marziale to a more lively Allegro mosso, which leads to an accelerando. This second characteristic is well recognizable, especially in the most accredited engravings of the autograph score.

From a musical point of view, the composition is divided into three parts: the introduction, the verses and the chorus.

The introduction consists of twelve measures, characterized by a dactylic rhythm that alternates an eighth note with two sixteenth notes. The first eight measures present a bipartite harmonic succession between B flat major and G minor, which alternate with the respective dominant chords of F major and D major seventh. This section is instrumental only. The last four bars, which introduce the sung part, return to b flat.

Therefore, the stanzas begin in b flat and are characterized by the repetition of the same melodic unit, repeated in various degrees and at different pitches. Each melodic unit corresponds to a fragment of Mameli's hexasyllable, whose emphatic rhythm moved Novaro, who set it to music according to the classical scheme of dividing the verse into two parts —Fratelli / d'Italia / l' Italy / s'è desta ("Brothers / of Italy / Italy / has awakened").

However, there is also an unusual choice, since the usual jump of a just interval does not correspond to the anachronusic rhythm. By contrast, the lines Fratelli / d'Italia and dell'elmo / di Scipio ("with the helmet / of Scipio") each carry, at the beginning, two identical notes, which can be fa or re as appropriate. This partly weakens the stress of the strong syllable in favor of the weak one, which aurally produces a syncopated effect, which contrasts with the short-long natural succession of the grave verse.

In the strong tempo of the basic melodic unit, an uneven group of dotted eighth notes and sixteenth notes is played.

Some musical reinterpretations of the Canto degli Italiani have tried to give more prominence to the melodic aspect of the composition, and, therefore, have softened this rhythmic sweep, bringing it closer to that of two notes of the same length (eighth notes).).

In measure 31, again with an unusual choice, the key changes to E flat major until the end of the melody, where it only yields to relative minor in the performance of the triplet Stringiamci a coorte / siam pronti alla morte / l'Italia chiamò ("Let us come together in a cohort / we are prepared for death / Italy called"), while time becomes an Allegro mosso. The chorus is also characterized by a repeated melodic unit several times. Dynamically, the last five bars increase in intensity, moving from pianissimo to forte to fortissimo with the indication crescendo e accelerando but alla fine ("growing and accelerating to the end").

Recordings

Copyright

Copyright expired because the work is in the public domain because both authors died more than 70 years ago. Novaro never asked for a fee to publish his music, attributing his work to the patriotic cause; to Giuseppe Magrini, who made the first printing of the Canto degli Italiani , he only asked for a certain number of copies for personal use. In 1859 Novaro, due to Tito Ricordi's request to reprint the text of the song in his publishing house, ordered that the money be paid directly in favor of a subscription to Garibaldi.

The score, on the other hand, is the property of the Sonzogno publishing house, which, therefore, has the possibility of making official copies of the piece. In 2010, after the scandal caused by a letter sent by the president of the municipal council of Messina Giuseppe Previti to the attention of the President of the Italian Republic, in which reference was made to the payment of more than 1000 euros requested from the local Red Cross for a New Year's concert, the Italian Society of Authors and Publishers (SIAE) renounced the direct collection of the rental rights of the musical scores of the Canto degli Italiani owed to the publishing house Sonzogno. The latter, owner of the scores, is in fact the publisher musical of the piece.

Older recordings

The oldest known sound document of the Canto degli Italiani —78 RPM record for gramophone, 17 cm in diameter— dates from 1901 and was recorded by the Municipal Band of the Municipality of Milan under the direction of master Pio Nevi.

One of the first recordings of Mameli's hymn was that of June 9, 1915, which was performed by the Neapolitan lyric and music singer Giuseppe Godono, under the Phonotype record label of Naples. Another early recording is that of the Grammophone Band, performed in London for the His Master's Voice label on January 23, 1918.

Protocol

Over the years, despite Mameli's anthem having provisional status, a protocol for its performance was established and is still in force. According to etiquette, during its performance, soldiers must present their weapons, while officers must stand their ground. Civilians, if they wish, can stand their ground as well.

According to the protocol, for official acts, only the first two stanzas should be interpreted without the introduction. If the event is institutional, and a foreign anthem is also going to be sung, it sounds first as an act of courtesy. In 1970 the obligation was decreed, which remained almost always unfulfilled, to perform the Ode to Joy by Ludwig van Beethoven, which is the official anthem of the European Union, whenever the song is performed. Canto degli Italiani.

Contenido relacionado

Japanese mythology

Sōkaku Takeda

Alberto Olmedo