Ieoh Ming Pei

Ieoh Ming Pei (English pronunciation: /joʊ.mɪŋ.ˈpeɪ/, April 26, 1917 – May 16, 2019) was a Chinese-American architect. Born in Guangzhou and raised in Hong Kong and Shanghai, Pei was inspired from an early age by the garden villas of Suzhou, a traditional retreat for the Chinese aristocracy, to which his family belonged. In 1935 he moved to the United States and enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania School of Architecture, but soon transferred to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was dissatisfied with the focus of both schools on beaux arts architecture and spent his spare time researching emerging architects, especially Le Corbusier. Upon graduation, he joined the Harvard Graduate School of Design and became friends with Bauhaus architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. In 1948, Pei was hired by New York real estate magnate William Zeckendorf, for whom he worked for seven years, until in 1955 he founded his own studio, I. M. Pei & Associates, which became I. M. Pei & Partners in 1966 and later Pei Cobb Freed & Partners in 1989. Pei retired from full-time professional practice in 1990, after which he worked as an architectural consultant primarily for his sons' firm, Pei Partnership Architects.

Pei's first major recognition came with the Mesa Laboratory at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado, designed in 1961 and completed in 1967. His new status led to his selection as chief architect of the John F. Kennedy in Massachusetts, and later designed Dallas City Hall and the East Building of the National Gallery of Art. He first returned to China in 1975 to design a hotel in Xiangshan Park, and fifteen years later he designed the Bank of China Tower, a skyscraper located in Hong Kong, for the Bank of China. In the early 1980s, Pei designed a controversial steel and glass pyramid for the Louvre Museum in Paris. He later returned to the art world designing the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas, the Miho Museum in Japan near Kyoto, the Suzhou Museum in Suzhou, the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, and the Grand Museum of Modern Art. Duke John (Mudam) in Luxembourg.

Pei has won a large number of awards and recognitions in the field of architecture, including the AIA Gold Medal in 1979, the first Praemium Imperiale for architecture in 1989, and the Award for History of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in 2003. In 1983, he won the Pritzker Prize, often referred to as the "Nobel Prize for architecture."

Childhood

Pei's ancestry dates back to the Ming dynasty, when his family moved from Anhui province to Suzhou. His family made a lot of money from herbal medicines, and this allowed him to become part of the Chinese aristocracy, a class that stressed the importance of helping the less fortunate.Ieoh Ming Pei was born on April 26, 1917; he was the son of Tsuyee and Lien Kwun. The family moved to Hong Kong a year later, and would eventually include five children. As a child, Pei was very close to his mother, a devout Buddhist renowned for her skills as a flutist. She invited Pei—and not her siblings—to accompany her to her spiritual retreats Her relationship with her father was less close; their interactions were respectful but distant.

The success of Pei's ancestors kept the family living in the upper echelons of society, but Pei said his father was "not cultivated in the art". Young Pei, drawn more to music and other cultural manifestations that through his father's field —banking—, he explored art by himself. "I have cultivated myself," he later said.

When Pei was ten years old, his father was promoted and moved his family to Shanghai. Pei attended St. John's High School, run by Anglican missionaries. The academic discipline was rigorous; students only had half a day each month for leisure. Pei liked to play pool and watch Hollywood movies, especially Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin movies. He also learned rudimentary English by reading the Bible and the novels of Charles Dickens.

Shanghai's many international elements earned it the nickname "Paris of the East". The city's overall architecture had a profound influence on Pei, from the Bund area to the Park Hotel, built in 1934. It also remained impressed by Suzhou's many gardens, where he spent summers with his family and regularly visited a nearby ancestral shrine. The Lion Garden, built in the 14th century by a Buddhist monk and owned by Pei's uncle Bei Runsheng, particularly influenced him. Its unusual rock formations, stone bridges, and waterfalls remained etched in his memory for decades. He would later express his appreciation for the mix of natural and man-made structures present in the garden.

Shortly after the move to Shanghai, Pei's mother fell ill with cancer. As a pain reliever for her, she was prescribed opium, and she charged Pei with the task of preparing her pipe. She passed away shortly after his thirteenth birthday, and he was particularly affected.The children went to live with his family; His father became more absorbed in his work and more physically distant. Pei said, “My father started living his own life separately from him soon after that.” His father later married a woman named Aileen, who would later move to New York.

Education and formative stage

As Pei neared the end of his secondary education, he decided to study at a university. He was accepted to several schools, but decided to enroll at the University of Pennsylvania.Pei's decision had two reasons. While studying in Shanghai, he had perused the programs at various institutions of higher learning around the world, and the architecture program at the University of Pennsylvania particularly caught his attention.The other deciding factor was Hollywood. Pei was fascinated by the depictions of university life in Bing Crosby films, which differed greatly from the Chinese academic atmosphere. "It seemed to me that college life in the United States was mostly fun and games," he said in 2000. "Since I was too young to be serious, I wanted to be a part of that... You can get the idea from Bing movies Crosby. University life in America seemed very exciting to me. He's not real, we know, but nonetheless, he was very attractive to me at the time. I decided it was the country for me.” Pei added that “Crosby's movies in particular had a big influence on him choosing the United States over England to pursue my education.”

In 1935 Pei sailed for San Francisco, and then took a train to Philadelphia. What he found when he arrived, however, differed greatly from his expectations. Professors at the University of Pennsylvania based his teachings in the beaux arts style, grounded in the classical traditions of ancient Greece and ancient Rome. Pei was more interested in modern architecture, and was also intimidated by the high level of drawing displayed by other students. He decided to drop architecture and transferred to the engineering program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). When he arrived, however, the dean of the school of architecture observed his capacity for design and convinced him to return to his original discipline.

MIT's school of architecture was also centered around the beaux arts school, and Pei was not inspired by his studies. However, in the library he found three books by the Swiss architect Le Corbusier. The innovative designs of the new rationalism, characterized by simple forms and the use of glass and crystal, did inspire Pei. Le Corbusier visited MIT in November 1935, an occasion that deeply impressed Pei: "The two days with Le Corbusier, or "Corbu" as we used to call it, were probably the most important days of my training as an architect." Pei was also influenced by the work of the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1938 he traveled to Spring Green (Wisconsin) to visit his famous Taliesin House; however, after waiting for two hours, he had to leave without being able to meet Wright.

Although he didn't like MIT's beaux arts approach, Pei excelled in his studies. "I certainly don't regret my time at MIT," she later said. "There I learned the science and technique of construction, which is essential to architecture." Pei received his bachelor's degree in architecture in 1940; His senior project was titled "Standardized Propaganda Units for Wartime and Peacetime in China."

While visiting New York in the late 1930s, Pei met a Wellesley College student named Eileen Loo. They began dating and were married in the spring of 1942. She enrolled in the landscape architecture program at Harvard University, and in this way Pei met the faculty of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD).. She was taken by the lively atmosphere of it, and she joined the GSD in December 1942.

Less than a month later, Pei suspended his job at Harvard to join the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), which coordinated scientific research on American weapons technology during World War II. Pei's background in architecture was considered a valuable asset; a committee member told him, “If you know how to build you must also know how to destroy.” The fight against Germany was ending, so his work focused on the Pacific War. The United States realized that the bombs they had used against the stone buildings of Europe would be ineffective against Japanese cities, built mainly of wood and paper, and for this reason they commissioned Pei to work on the incendiary bombs. Pei spent two and a half years at the NDRC, but revealed few details of his work.

In 1945 Eileen gave birth to a son, T'ing Chung, and gave up her studies in landscape architecture to care for him. Pei returned to Harvard in the fall of 1945 and received a position as an assistant professor of design. The GSD was becoming a nucleus of resistance against beaux arts orthodoxy, and at its center were members of the Bauhaus, a European architectural movement that had advanced the cause of modern design. The Nazi regime had condemned the Bauhaus school, and its leaders left Germany. Two of them, Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, held prominent positions at the Harvard GSD. Their iconoclastic approach to modern architecture appealed to Pei, and he worked closely with both of them.

One of Pei's design projects at GSD was an art museum in Shanghai. She wanted to create a sense of Chinese authenticity in the architecture without using traditional materials or styles.The design was based on straight modern structures, organized around a central courtyard with a garden, and had other similar natural settings. It was very well received; in fact, Gropius said it was "the best project done in my class". Pei received his master's degree in architecture in 1946, and continued to teach at Harvard for another two years.

Career

1948–1956: beginnings with Webb and Knapp

In the spring of 1948, Pei was hired by New York real estate magnate William Zeckendorf and joined a firm of architects working to design buildings across the country for the Zeckendorf-owned firm of Webb and Knapp. Pei found Zeckendorf's personality to be the opposite of his own: his new boss was known for her high-pitched voice and his gruff attitude. Nonetheless, they became good friends and Pei found the experience enriching on a personal level. Zeckendorf was well connected politically, and Pei enjoyed learning about the social lives of New York city planners.

His first project for Webb and Knapp was an apartment building with funding from the 1949 housing law. Pei's design was based on a circular tower with concentric rings. The sectors closest to the central support pillar housed services and circulation areas, while the apartments were located towards the outside. Zeckendorf loved the design and even showed it to Le Corbusier when he met him when they found it. However, the cost of such an unusual design was too high, and the building was never more than a mock-up.

Finally, Pei first saw his architecture come to life in 1949, when he designed a two-story corporate building for Gulf Oil in Atlanta, 131 Ponce de León Avenue. The building was demolished in February 2013 although the main façade was preserved. The use of marble for the exterior curtain wall was praised by Architectural Forum magazine. Early in his career, Pei's designs replicated the work of Mies van der Rohe, as also shown by his own weekend home built in Katonah in 1952. Soon Pei was so inundated with projects that he asked Zeckendorf for assistants, choosing from his GSD associates such as Henry N. Cobb and Ulrich Franzen. Together they went to work on various projects, such as the Roosevelt Field shopping center. The team also redesigned the Webb and Knapp office building, transforming Zeckendorf's office into a circular space with teak walls and a glass clerestory. They also installed a control panel on the desk that allowed his boss to control the lighting in his office. The project took a year to complete and was over budget, but Zeckendorf was delighted with the result.

In 1952 Pei and his team began work on a series of projects in Denver. The first of these was the Mile High Center, in which he made the central building occupy less than 25% of the lot; the remainder housed an exhibition hall and fountain plazas. A block away, Pei's team also redesigned Courthouse Square, which combined office, retail, and hotel spaces. These projects helped Pei conceptualize architecture as part of urban geography. “I learned about the urbanization process,” he later said, “and about the city as a living organism.” These lessons, he said, would be essential to his later projects.

Pei and his team also designed an urban complex for Washington, D.C., named L'Enfant Plaza after French-American architect Pierre Charles L'Enfant. Pei's partner Araldo Cossutta he was the chief architect of the complex's north building (955 L'Enfant Plaza SW) and the south building (490 L'Enfant Plaza SW). Vlastimil Koubek was the architect of the east building (L'Enfant Plaza Hotel, located at 480 L'Enfant Plaza SW) and the Central Building (475 L'Enfant Plaza SW, currently the United States Postal Service headquarters). The team proposed a sprawling complex that was praised by both The Washington Post and the Washington Star—who rarely agree on anything—but funding problems forced revisions and a reduction important of the scale.

In 1955 Pei's group took a step toward institutional independence from Webb and Knapp by founding a new firm called I. M. Pei & Associates, later changed to I. M. Pei & Partners. This gave them the freedom to work for other companies, but they continued to work mainly for Zeckendorf. The new study distinguished itself by its use of detailed mock-ups. In the Kips Bay suburb of Manhattan's east side, Pei designed the Kips Bay Towers, two large apartment towers with recessed windows—to provide shade and privacy—arranged in an orderly grid. Pei was personally involved in the construction, even going so far as to inspect the bags of concrete for color consistency.

The company continued its urban focus with the Society Hill project in downtown Philadelphia. Pei designed Society Hill Towers, a three-building residential block that injected cubist design into the neighborhood's 18th century setting. As with previous projects, abundant green spaces were central to Pei's vision, which he also added traditional petit hôtels to help smooth the transition between classic and modern design.

Between 1958 and 1963 Pei and Ray Affleck developed a key downtown Montreal block through a phased process that included one of Pei's most admired buildings in the Commonwealth, the cruciform tower known as Royal Bank Plaza (Place Ville Marie). According to The Canadian Encyclopedia, “its grand plaza and office buildings, designed by the renowned international architect I.M. Pei, helped set new architectural standards in Canada in the 1960s…The smooth surface of aluminum and The tower's glass and crisp, unadorned geometric form demonstrate Pei's adherence to the mainstream of 20th century” modern design.

Although these projects were successful, Pei wanted to make an independent name for himself. In 1959 he was contacted by MIT to design a building for its Earth sciences program. In his Green Building project, Pei continued the grid layout of Kips Bay and Society Hill. The pedestrian walkway on the ground floor, however, was prone to sudden gusts of wind, which embarrassed Pei. “Here I was from MIT,” he said, “and I didn't know about wind tunnel effects.” At the same time, he designed the Luce Memorial Chapel at Tunghai University in Taichung, Taiwan. This imposing structure, commissioned by the same organization that had run his high school in Shanghai, made a dramatic break with the gridded cubist patterns of his previous urban projects.

The challenge of coordinating these projects took an artistic toll on Pei, as he was responsible for securing new commissions and overseeing the projects. As a result, he felt disconnected from real creative work. "Design is something you have to put your hand on," he said. "While my people had the luxury of doing one job at a time, I had to keep track of the entire company." His dissatisfaction reached a fever pitch at a time when financial problems began to plague the company. from Zeckendorf. I. M. Pei and Associates officially broke with Webb and Knapp in 1960, which benefited Pei artistically but hurt him personally, as he had developed a close friendship with Zeckendorf, and both were saddened to part ways.

NCAR and related projects

Pei was able to return to design when he was commissioned in 1961 by Walter Orr Roberts to design the new Mesa Laboratory for the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) near Boulder, Colorado. This project differed from Pei's previous urban works: it was located in an open area in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. He toured the area with his wife, visiting different buildings and inspecting the natural surroundings. He was impressed by the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, but felt that it was "separated from nature."

The conceptualization phase was very important to Pei, as it presented both the need and the opportunity to break with the Bauhaus tradition. Later he recalled the long periods of time he spent in the area: “I remembered the places I had seen with my mother when I was a child, the Buddhist retreats located on top of a mountain. There, in the mountains of Colorado, I tried to listen to the silence again, as my mother had taught me. Researching the area became a kind of religious experience for me." Pei was also inspired by the Anasazi carved mountain dwellings in Mesa Verde National Park; he wanted the buildings to exist in harmony with their natural surroundings.To this end, he called for a rock treatment process that could make the color of the buildings match that of the nearby mountains. He also placed the complex facing the city, and designed a long, winding, indirect access road.

Roberts disliked Pei's initial designs, calling them "just a bunch of towers". Roberts made this comment as typical of scientific experimentation, rather than artistic criticism; however, Pei was left frustrated. His second attempt, however, fit perfectly with Roberts' vision: a spaced series of clustered buildings, linked by lower structures and complemented by two subterranean levels. The complex uses many cubist design elements, and the walkways are arranged to increase the likelihood of chance encounters between colleagues.

Once the lab was built, various problems appeared with its construction. Roof leaks caused difficulties for investigators, and shifting clay soil under the complex caused cracks in the buildings, which were expensive to repair. However, both the architect and the project manager were satisfied with the end result. Pei referred to the NCAR complex as his "breakthrough building", and remained friends with Roberts until the scientist passed away in March 1990.

The success of NCAR brought renewed attention to Pei's design prowess. For this reason, he was hired to work on various projects, such as the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University, the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, the Sundrome Terminal at New York's John F. Kennedy International Airport, and the New College of Florida residence halls.

Kennedy Library

After President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, his family and friends discussed how to build a library that would serve as a proper memorial. A committee was formed to advise Kennedy's widow, Jacqueline, who would make the final decision. The committee deliberated for months and considered many famous architects. Ultimately, Kennedy chose Pei to design the library, based on two considerations. First, he appreciated the variety of ideas that he had used for previous projects. "It seemed like he didn't have just one way to solve a problem," he said. "He seemed to approach each assignment with only him in mind and then develop a way of making something beautiful."Ultimately, however, Kennedy made his decision based on his personal connection to Pei, saying it was "an emotional decision." ». He explained: "He had so much potential, like Jack; they were born in the same year. I decided it would be fun to take on the project with him."

The project was plagued with problems from the start. The first was its reach. President Kennedy had begun considering the structure of his library shortly after taking office, and wanted to include his administration's archives, a museum of personal belongings, and a political science institute. Following his assassination, the list was expanded to include a memorial tribute to the late president. The large number of intended uses complicated the design process and caused significant delays.

Pei's first proposed design included a large glass pyramid that would fill the interior with natural light and was intended to represent the optimism and hope that the Kennedy administration had symbolized for many Americans. Jacqueline Kennedy liked the design, but there was opposition in Cambridge, the first proposed site for the building, from the time the project was announced. Many community members were concerned that the library would become a tourist attraction and cause problems, particularly with traffic congestion. Others worried that the design would clash with the architectural style of nearby Harvard Square. In the mid-1970s, Pei attempted to propose a new design, but the library's opponents resisted all his efforts. These events affected Pei, who had sent his three children to Harvard, and although he rarely commented on his frustration, was obvious to his wife: "I could tell how tired he was by the way he opened the door at the end of the day," he said. «She dragged her steps. It was very hard for him to see that so many people did not want the building."

Eventually, the project was moved to Columbia Point, near the University of Massachusetts in Boston. The new site wasn't ideal: it was situated in an old dump, and right above a large sewage pipe. Pei's team added more padding to cover the pipe and developed an elaborate ventilation system to neutralize the odor. A new design was unveiled, combining a large square glass-covered atrium with a triangular tower and circular walkway.

The John F. Kennedy Library opened on October 20, 1979. Critics generally liked the building, but the architect was not pleased. Years of conflict and compromise had changed the nature of the design, and Pei felt the end result lacked his original passion. “I wanted to give something very special to the memory of President Kennedy,” he said in 2000. “It could and should have been a great project.” Pei's work on the Kennedy project, however, enhanced his reputation as an architect..

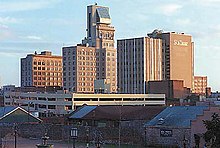

Pei Plan, Oklahoma City

The Pei Plan was an unsuccessful redevelopment initiative designed for downtown Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, in the 1960s and 1970s. It is the informal name for two related commissions by Pei, the Central Business District General Neighborhood Renewal Plan (design completed 1964) and the Central Business District Project I-A Development Plan (design completed 1966). It was formally adopted in 1965, and implemented in various public and private phases during the 1960s and 1970s.

The project called for the demolition of hundreds of old downtown buildings in favor of new parking, office and retail developments, as well as public projects such as a convention center and botanical gardens. It was the dominant model for the development of downtown Oklahoma City from its inception until the 1970s. The project generated mixed opinions: it got offices and parking lots built but failed to attract the anticipated commercial and residential developments. Significant public opposition also developed as a result of the destruction of many historic buildings. As a result, the Oklahoma City council eschewed large-scale development projects in downtown during the 1980s and early 1990s, until the passage of the Metropolitan Area Projects (MAPS) initiative in 1993.

Cathedral Square, Providence

Another city that turned to Pei for its urban renewal at this time was Providence, Rhode Island. In the late 1960s, Providence hired Pei to redesign Cathedral Square, a once-busy square that had become abandoned, as part of a larger, ambitious project to redevelop Downtown. Pei's new plaza, modeled after a Greek agora, opened in 1972. Unfortunately, the city ran out of money before Pei's vision came to fruition. fully realized. In addition, the recent construction of a social housing complex and Interstate 95 had permanently changed the character of the neighborhood. In 1974, The Providence Evening Bulletin called the new square of Pei a "notorious failure". In 2016, however, the square was considered by the media to be an abandoned and little-seen "hidden treasure".

Augusta, Georgia

In 1974, the city of Augusta, Georgia turned to Pei and his studio for the revitalization of downtown. The Chamber of Commerce building and Bicentennial Park were also built as part of his project. In 1976, Pei he designed a distinctive modern penthouse on the roof of the historic Lamar Building, designed by William Lee Stoddart in 1916. This penthouse is a modern interpretation of a pyramid, anticipating Pei's famous pyramid at the Louvre Museum. It was criticized by architecture critic James Howard Kunstler for being the "atrocity of the month", and he compared it to Darth Vader's helmet.In 1980, Pei and his firm designed the Augusta Civic Center, now known as James Brown Arena.

Dallas City Hall

Kennedy's assassination also indirectly prompted another assignment for Pei's studio. In 1964, Dallas' acting mayor Erik Jonsson began working to change the city's image. Dallas was remembered for being the city where the president was assassinated, but Jonsson launched a program designed to initiate a renewal of the town. One of the goals was a new city hall that could be a "symbol of the people". Jonsson, co-founder of Texas Instruments, learned of Pei's work through his partner Cecil Howard Green, who had hired the architect for the MIT Green Building..

Pei's approach to the new Dallas City Hall was similar to other projects: he surveyed the surroundings and worked to make the building fit into its surroundings. In the case of Dallas, he spent several days meeting with city residents and was impressed by their civic pride. He also observed that the skyscrapers of the financial district dominated the views of the city, and he tried to create a building that could face them and represent the importance of the public sector. He spoke of creating a "public-private dialogue with office skyscrapers."

Together with his partner Theodore Musho, Pei developed a design centered around a building with a top wider than the bottom; the façade leans at an angle of 34 degrees, which protects the building from sunlight. There is a square before the building, and a series of pillars supports it. His design was inspired by Le Corbusier's Chandigarh (India) Secretariat Building. Pei intended to use the considerable overhang to unify the building and the plaza. The project cost much more than initially anticipated, taking eleven years to complete. A car park with a capacity for 1,325 vehicles was built under the square, and the extra income helped finance the construction. The interior of the town hall is large and spacious; ceiling windows above the eighth floor fill the main space with light.

The city of Dallas welcomed the new City Hall, and when it officially opened to the public in 1978 it met with unanimous approval among local television stations. Pei himself considered the project a success, despite the fact that he was concerned about the arrangement of its elements. He said, "It's perhaps stronger than I would have liked, it has more strength than finesse." He felt that his relative lack of experience had left him without the design tools necessary to refine his vision, but the community liked the enough to commission projects from him again: over the years he would design another five buildings in the Dallas area.

Hancock Tower, Boston

While Pei and Musho were coordinating the Dallas project, their partner Henry Cobb had taken the reins on a commission in Boston. John Hancock Insurance President Robert Slater hired I. M. Pei & Partners to design a building that would outshine the Prudential Tower, built by their rival company, Prudential Insurance.

After the studio's first project was scrapped due to the need for more office space, Cobb developed a new project consisting of a parallelogram-shaped skyscraper, rotated relative to Trinity Church and accentuated by a cutaway wedge-shaped on each of the short sides. To minimize the visual impact, the building was covered with large reflective glass panels; Cobb said this would make the building "background" to the older buildings that surround it. When completed in 1976, Hancock Tower became the tallest building in New England.

Some serious execution issues in the tower became apparent almost immediately. Many glass panels broke in a wind storm during its construction in 1973. Some of them broke off and fell to the ground, causing no injuries but causing concern to Boston residents. In response, the entire tower was clad in smaller panels. This significantly increased the cost of the project. Hancock sued the glass suppliers, Libbey-Owens-Ford, and I.M. Pei & Partners, for submitting projects that were "neither good nor professional". Libbey-Owens-Ford sued Hancock for defamation, accusing Pei's studio of misusing its materials; I.M. Pei & Partners sued Libbey-Owens-Ford in return. The three companies settled out of court in 1981.

The project became a liability to Pei's studio. Pei himself refused to talk about him for many years. The pace of new commissions slowed and the studio's architects began looking for opportunities in other countries. Cobb worked in Australia and Pei received commissions in Singapore, Iran and Kuwait. Although it was a difficult time for all involved, Pei patiently reflected on the experience afterwards. "Going through this trial made us stronger," he said. "It helped us consolidate ourselves as partners, we didn't give up."

National Gallery East Building, Washington D.C.

In the mid-1960s, the directors of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. expressed the need for a new building. Paul Mellon, one of the gallery's main benefactors and a member of its building committee, went to work with his assistant J. Carter Brown—who would become gallery director in 1969—to find an architect. The new structure would be located to the east of the original building, and had two functions: to provide a large space for public appreciation of various popular collections, and to house offices and archives. They compared the scope of the new facility to the Alexandria library. After examining Pei's work at the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa and the Johnson Museum at Cornell University, they decided to offer him the commission.

Pei took to the project with energy, working with two young architects he had recently hired for his studio, William Pedersen and Yann Weymouth. Their first hurdle was the unusual shape of the parcel, a trapezoid of land at the intersection of Avenida de la Constitución and Avenida Pennsylvania. Inspiration came to Pei in 1968, when he scribbled a diagram of two triangles on a piece of paper. The largest building would be the public gallery, and the smallest would house the offices and archives. This triangular shape became a singular vision for the architect. As the construction start date approached, Pedersen suggested to his boss that a slightly different approach would make construction easier. Pei simply smiled and said, "No concessions."

The growing popularity of art museums presented unique challenges for architecture. Mellon and Pei expected large crowds of people to visit the new building, and they designed it accordingly. For this purpose, Pei designed a large hall covered with huge skylights. Individual galleries are located along the periphery, allowing visitors to return to the spacious main room after visiting each exhibition. A large mobile sculpture by American artist Alexander Calder was later placed in the lobby. Pei hoped the lobby would be "exciting" to the public in the same way as the central hall of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. The modern museum, he later said, "must pay more attention to its educational responsibility, especially of the young."

The materials for the exterior of the building were chosen with careful precision. To match the look and texture of the original gallery's marble walls, the builders reopened the Knoxville, Tennessee quarry from which the first batch of stone was extracted, and even sought out and hired stoneworker Malcolm Rice. quarry who had overseen the original 1941 gallery project. The marble was cut into 8cm thick blocks and laid on top of the concrete foundation, with darker blocks on the bottom and lighter blocks on top.

The East Building was inaugurated on May 30, 1978, two days before its public opening, with a gala party attended by celebrities, politicians, benefactors, and artists. When it opened to the public, popular opinion was enthusiastic. Large crowds visited the new museum, and critics generally expressed their approval. Ada Louise Huxtable wrote in The New York Times that Pei's building was "a sumptuous statement of the creative accommodation of contemporary art and architecture". The sharp angle of the smaller building has been a particular note. of praise for the public; over the years it has been stained and worn by the hands of visitors.

However, some critics did not like the unusual design, criticizing the reliance on triangles throughout the building. Others took issue with the grand main lobby, particularly its attempt to attract casual visitors. In his review for Artforum, Richard Hennessy described a "comic atmosphere" and an "aura of ancient Roman patronage". However, one of the earliest and greatest critics came to appreciate the new gallery when it was opened. saw in person Allan Greenberg had criticized the design when it was first unveiled, but later wrote to J. Carter Brown: "I am forced to admit that you were right and I was wrong. The building is a masterpiece."

Fragrant Hill Hotel, China

After US President Richard Nixon made his famous visit to China in 1972, a wave of exchanges took place between the two countries. One of these was a delegation from the American Institute of Architects sent in 1974, in which Pei participated. It was his first trip to China since he left for America in 1935. He was favorably received, welcomed back with positive comments, and a series of lectures followed. Pei noted at one of these lectures that since the 1950s Chinese architects had been content to imitate Western styles, and he urged his audience to look to Chinese traditions for inspiration.

In 1978, Pei was asked to start a project for his home country. After inspecting several different locations, Pei fell in love with a valley known as Xiangshan Park, which had once served as an imperial garden and game reserve. The place housed a decrepit hotel; they proposed to Pei that he tear it down and build a new one. As always, to start the project he carefully considered the context and usage, and concluded that modern styles were inappropriate for the setting. Therefore, he said it was necessary to find "a third way."

After visiting his ancestral home in Suzhou, Pei created a design based on some simple but nuanced techniques he admired in traditional Chinese residential buildings. Among these techniques were abundant gardens, integration with nature, and consideration of the relationship between closure and openness. Pei's design included a large central atrium covered with glass panels that functioned in a similar way to the large central space in his National Gallery East Building. Openings of various shapes in the walls invited guests to view the natural setting in which the hotel was located. Younger Chinese, who had expected the building to display some of the cubist style Pei was known for, were disappointed, but the new hotel was better received by architects and government officials.

Comprising 325 rooms and a four-story central atrium, the hotel was designed to blend seamlessly into its natural surroundings. The trees in the area were of particular interest, and particular care was taken to fell as few of them as possible. He worked with an expert from Suzhou to preserve and renovate a water maze from the original hotel, one of only five in the entire country. Pei was also very meticulous with the arrangement of the elements in the garden behind the hotel; he even insisted on transporting 210 tons of rocks from southwest China to suit the natural aesthetic. An associate of Pei's later said that he had never seen him so involved in a project.

During construction, a series of errors added to the country's lack of technology to strain relations between architects and builders. Whereas in the United States some 200 workers would have been used for a similar building, more than 3,000 people worked on the Xiangshan Park project. This was mainly because the construction company did not have the sophisticated machines used in other countries. The troubles continued for months, until Pei had an unusual outburst of temper in a meeting with Chinese officials. He later explained that he "screamed and banged the table" in frustration.The design team noted a difference in the way the staff worked after the meeting. As the opening neared, however, Pei noted that the hotel still needed work. He started cleaning floors with his wife and ordered his children to make the beds and vacuum the floors. The difficulties of the project took a physical and emotional toll on Pei's family.

The Fragrant Hill Hotel opened on October 17, 1982 but quickly fell into disrepair. A member of Pei's team returned for a visit several years later and confirmed the hotel's neglected condition. He and Pei attributed this to a general unfamiliarity with the country's luxury buildings. The Chinese architectural community paid little attention to the building at the time, as its interest then centered on the work of American postmodernists such as Michael Graves.

Javits Convention Center, New York

As the Xiangshan Park project neared completion, Pei began working on the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in New York, for which his partner James Freed served as lead designer. Hoping to create a vibrant community institution in what was then a depressed neighborhood on Manhattan's West Side, Freed developed a glass-encased structure with an intricate spatial mesh of metal bars and interconnected spheres.

Convention center construction was plagued from the start by budget problems and construction errors. City regulations prohibit a general contractor from having final authority over the project, so the architects and program manager Richard Kahan had to coordinate the myriad of builders, plumbers, electricians and other workers. Forged steel balloons to be used in the space mesh arrived at the parcel with hairline cracks and other defects: twelve thousand of them were rejected. These and other problems prompted comparisons to the disastrous Hancock Tower in the media. A New York official blamed Kahan for the difficulties, stating that the building's architectural flourishes were responsible for the delays and financial crises. The Javits Center opened on April 3, 1986, to generally positive reception. During the opening ceremonies, however, neither Freed nor Pei were recognized for their role in the project.

Pyramid of the Louvre Museum, Paris

When François Mitterrand was elected president of France in 1981, he drew up an ambitious plan that included several architectural projects. One of these was the renovation of the Louvre Museum; Mitterrand appointed a civil servant named Émile Biasini to supervise him. After visiting museums in Europe and the United States, including the National Gallery of Art, he asked Pei to join the team. The architect made three secret trips to Paris to determine the feasibility of the project; Only a museum employee knew why he was there.Pei eventually accepted that a rebuilding project was not only possible, but necessary for the museum's future. He thus became the first foreign architect to work on the Louvre.

The new project included not only a renovation of the Cour Napoléon, which is located at the center of the buildings, but also a transformation of the interiors. Pei proposed a central entrance, not unlike the lobby of the East Building of the National Gallery, which would connect the three main buildings. Below would be a complex of several floors dedicated to research, storage and maintenance. In the center of the courtyard he designed a glass and steel pyramid, first proposed for the Kennedy Library, to serve as the entrance and skylight. This pyramid was reflected by another inverted pyramid below, which reflected sunlight into the room. These designs were partly a tribute to the delicate geometry of the famous French landscape architect André Le Nôtre (1613–1700). Pei also considered the pyramid shape the most appropriate for achieving stable transparency, saying it was "the most compatible with the architecture of the Louvre, especially with the faceted planes of its roofs".

Biasini and Mitterrand liked the project, but the scope of the renovation upset Louvre director André Chabaud, who resigned, complaining that the project was "unfeasible" and posed "architectural risks." The public also reacted strongly to the design, mainly due to the pyramid. One critic called it "a gigantic and ruinous contraption"; another accused Mitterrand of "despotism" for imposing the "atrocity" on Paris. Pei estimated that 90% of Parisians were opposed to his design. “I got a lot of angry looks on the streets of Paris,” he said, some of which had nationalist overtones. For example, one opponent wrote: "I am surprised that a Chinese architect is being sought out in America to deal with the historic heart of the French capital."

Soon, however, Pei and his team enlisted the support of several cultural icons, including conductor Pierre Boulez and Claude Pompidou, the widow of former president Georges Pompidou, in whose honor another controversial museum was dedicated. In an attempt to calm public anger, Pei followed a suggestion by then-Paris mayor Jacques Chirac and set up a full-scale wireframe model of the pyramid in the courtyard. During the four days it was on display, some 60,000 people visited the site, with some critics easing their opposition after appreciating the proposed scale of the pyramid.

To minimize the impact of the structure, Pei required that a glass production method be used that would make transparent panels. The pyramid was built at the same time as the underground levels below, which caused some difficulties during construction. While working, the construction crews discovered a set of abandoned rooms containing twenty-five thousand historical objects; these were incorporated into a new exhibition area that had to be added to the complex.

The Louvre's new courtyard opened to the public on October 14, 1988, and the pyramid entrance opened in March of the following year. By this time, public opinion about the new facility had softened; one poll found that 56% approved of the pyramid, while 23% still opposed it. The newspaper Le Figaro had vehemently criticized Pei's design, but later celebrated the tenth anniversary of its supplement magazine with a feature on the pyramid. Prince Charles of the United Kingdom inspected the site curiously, and considered it "wonderful, very exciting". A journalist wrote in Le Quotidien de Paris : "The much feared pyramid has become adorable". The experience was exhausting for Pei, but also rewarding.. “After the Louvre,” he later said, “I thought no project would be too difficult.” The Louvre Museum's pyramid has become Pei's most famous work.

Meyerson Symphony Center, Dallas

The opening of the Louvre pyramid coincided with four other projects Pei had been working on. This prompted architecture critic Paul Goldberger to declare 1989 "the year of Pei" in The New York Times.It was also the year his firm changed its name to Pei Cobb Freed &; Partners to reflect the growing specific weight of her partners. At seventy-two years of age, Pei had begun to think about retirement, but continued to work long hours to bring his designs to life.

One of these projects brought Pei back to Dallas, to design the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center. The success of the city's performing artists, particularly the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, directed at the time by Eduardo Mata, prompted the interest of Dallas leaders in creating a modern concert hall that could rival the best halls in Europe. The organizing committee contacted forty-five architects, but Pei did not respond at first, thinking that his work at the Dallas City Hall had left a negative impression. However, one of his colleagues on that project insisted that he meet with the committee; Pei did so, and although it would be his first concert hall, the committee voted unanimously to offer him the commission. As one of its members declared: "We were convinced that we would get the best architect in the world to give his best."

The project presented several specific challenges. As its main use would be for the presentation of live music, the building needed to have a design focused first on acoustics, and then on public access and exterior aesthetics. For this reason, they hired a sound technician to design the interior, who proposed a shoebox-shaped auditorium, just like some of the best European symphony halls, such as the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam and the Musikverein in Vienna. For the adjustments he made to the design, Pei was inspired by the work of the German architect Johann Balthasar Neumann, and especially by the Vierzehnheiligen basilica. He also sought to incorporate part of the style of the Opera Garnier in Paris, designed by Charles Garnier.

Pei placed the shoebox at the corner of the surrounding street grid. He connected it to the north with a long rectangular office building, and cut it in half with a set of circles and cones. In her design, she tried to reproduce with modern elements the acoustic and visual functions of traditional elements such as filigrees. The project was risky: its goals were ambitious, and any unforeseen acoustic defects would be nearly impossible to fix after the building was completed. Pei admitted that he didn't fully know how all the elements would come together. "I can only imagine 60% of the space in this building," he said during the early phases. "The rest will be just as surprising to me as it is to everyone else." As the project developed, costs continually increased, and some backers considered withdrawing their support. Billionaire Ross Perot made a $10 million gift on the condition that it be named after Morton H. Meyerson, a longtime patron of art in Dallas.

Upon its opening, the building immediately garnered widespread acclaim, especially for its acoustics. After attending a week of performances at the center, a music critic for The New York Times wrote an enthusiastic account of the experience and congratulated the architects. One of Pei's associates told him at a party before the opening that this concert hall was "a very mature building"; He smiled and replied: "But, did I have to wait that long?"

Bank of China Tower, Hong Kong

In 1982 Pei received a new offer from the Chinese government. With an eye toward the British transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong in 1997, Chinese authorities sought Pei's help for a new tower for the local Bank of China branch. The Chinese government was gearing up for a new wave of outward engagement and was looking for a tower that represented modernity and economic strength. Given his father's relationship with the bank before the communists came to power, government officials visited Pei's eighty-nine-year-old father in New York to get approval for his son's involvement.. Next, Pei spoke at length with his father about the proposal. Although the architect recalled the difficulties of his experience with the Xiangshan Park Hotel, he decided to accept the commission.

The proposed location for the building in Hong Kong's Central district was far from ideal: a tangle of roads surrounded it on three sides. Additionally, the area had housed a Japanese military police headquarters during World War II, and was known for the torture of prisoners. The small size of the plot made a tall tower necessary, and Pei had generally avoided such projects; especially in Hong Kong, skyscrapers had no real architectural character. Uninspired and unsure about how to approach the building, Pei took a weekend vacation to his home in Katonah. There he experimented with a bundle of chopsticks until he found a cascading string.

Pei felt that his design for the Bank of China Tower had to reflect the "aspirations of the Chinese people". The design he developed for the skyscraper was not only unique in appearance, but also strong enough to pass the rigorous standards of resistance to the wind of the city. The building is made up of four triangular shafts that rise from a square base, supported by a visible frame that distributes the load to the four corners of the base. Using reflective glass, which had become something of a trademark, Pei organized the façade around diagonal bracing in a union of structure and form that echoes the triangular motif established in the project. At the top, he designed pitched roofs that complemented the rising aesthetic of the building. Some influential Hong Kong and Chinese feng shui advocates criticized the design, and Pei and government officials responded with some adjustments.

As the tower neared completion, Pei was shocked to witness the government massacre of unarmed civilians in the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. He wrote an op-ed for The New York Times titled "China will never be the same again", in which he said that these murders "torn the heart of a generation that carries hope for the future of the country". The massacre deeply disturbed his entire family, and wrote that "China is sullied".

1990–2019: museum projects

As the 1990s began, Pei moved into a less involved role with his studio. The staff had started to dwindle, and Pei wanted to pursue smaller projects that would allow for more creativity. Before he made this switch, however, he went to work on his last major project as an active member: the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio. Considering his work in bastions of high culture like the Louvre or the National Gallery in Washington, some critics were struck by his association with what many considered a tribute to low culture. The patrons of the salon, however, sought out Pei specifically for this reason; they wanted the building to have an aura of respectability from the start. As in the past, Pei accepted the assignment partly because of the challenge he presented.

Using a glass wall for the entrance, similar in appearance to his Louvre pyramid, Pei clad the exterior of the main building in white metal, placing a large cylinder on a narrow pillar to serve as a performance space. The combination of off-center envelopes and sloped walls was, in Pei's words, designed to provide a "feeling of tumultuous youthful energy, rebelling, agitating".

The building opened in 1995 and was met with moderate praise. The New York Times called it "a fine building," but Pei was among those disappointed with the result. The museum's New York beginnings, combined with an unclear mission, created a confused understanding among project leaders of exactly what was needed. Although the city of Cleveland benefited greatly from the new tourist attraction, Pei was unhappy with her.

At the same time, Pei designed a new museum for Luxembourg, the Musée d'art moderne Grand-Duc Jean, commonly known as Mudam. Based on the original shape of the walls of Fort Thüngen, where the museum was located, Pei proposed removing a part of the original foundation. However, public resistance to this historic loss forced a review of the project, and it was all but abandoned. The size of the building was reduced by half, and it was set back from the original wall to preserve the foundations. Pei was disappointed with the alterations, but remained involved in the building construction process.

In 1995, Pei was hired to design an extension to the German Historical Museum in Berlin. Returning to the challenge of the East Building of the National Gallery in Washington, Pei worked to combine a modern approach with a classical main structure. He described the glass cylinder he added as a "lighthouse," and topped it with a glass roof to let plenty of sunlight into the interior. Pei had difficulties with German government officials; his utilitarian approach clashed with his passion for aesthetics. "They thought it was just trouble," he said.

Pei also worked around this time on two projects for a new Japanese religious movement called Shinji Shumeikai. He was contacted by the movement's spiritual leader, Kaishu Koyama, who impressed the architect with her sincerity and his willingness to give her significant artistic freedom. One of the buildings was a bell tower, designed to resemble the bachi used when playing traditional instruments such as the shamisen. Pei wasn't familiar with the movement's beliefs, but he explored them to create something meaningful in the tower. In his own words, "it was a search for expression that is not technical at all."

The experience was rewarding for Pei, and he immediately agreed to work with the group again. The new project was the Miho Museum, which was to be built to display Koyama's collection of tea ceremony artifacts. Pei visited the site in Shiga Prefecture, and during their talks he convinced Koyama to expand his collection. She conducted a global search and acquired more than three hundred objects showing the history of the Silk Road.

A major challenge was access to the museum. The Japanese team proposed a winding path up the mountain, not unlike the access to the NCAR building in Colorado. Instead, Pei ordered a tunnel cut through a nearby mountain, which was connected to a highway by a suspension bridge of ninety-six steel cables, supported by a pole set into the mountain. The museum itself was built inside the mountain, with 80% of the space underground.

When designing the exterior, Pei was inspired by the tradition of Japanese temples, particularly those located near Kyoto. He created a concise spatial mesh clad in French limestone and covered with a glass roof. Pei also oversaw the decorative details, such as a bench in the entry hall, carved from a three-hundred-fifty-year-old keyaki tree. Due to Koyama's considerable wealth, money was rarely considered an obstacle; at the time of its completion, the project was estimated to cost about $350 million.

During the first decade of the xxi century, Pei designed several buildings, including the Suzhou Museum, near his childhood home. designed the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (Qatar) at the request of the Al-Thani family. Although originally planned to be located on the Doha Bay highway, Pei convinced project coordinators to build a new island, which would give it a more prominent location. The architect spent six months touring the region and visiting mosques in Spain, Syria and Tunisia, and was especially impressed with the elegant simplicity of Cairo's Ibn Tulun Mosque.

Once again, Pei sought to combine new design elements with the classic aesthetic most appropriate to the building's location. Her design is made up of rectangular sand-colored boxes that rotate evenly to create subtle movement, with small arched windows set at regular intervals in the limestone exterior. Inside, the galleries are arranged around a large atrium, illuminated from above. The project coordinators were satisfied with the result; its official website describes its "true splendor unveiled in the sunlight," and speaks of "color tones and shadow interplay that pay tribute to the essence of Islamic architecture."

The Macau Science Center was designed by Pei Partnership Architects in collaboration with I. M. Pei. The center project was completed in 2001 and construction began in 2006. The center was completed in 2009 and inaugurated by Chinese President Hu Jintao. The main part of the building has a characteristic conical shape with a spiral walkway and a large atrium inside, similar to the one in the Guggenheim Museum in New York. From this walkway exit the galleries, which consist mainly of interactive exhibitions aimed at science education. The building stands in a prominent position by the sea and is currently one of the symbols of Macau, Pei's career ended with his death in May 2019.

Style and method

Pei's style has been described as thoroughly modern, with significant cubist influences. He was known for combining traditional architectural principles with progressive designs based on simple geometric patterns: circles, squares, and triangles are common elements of his work, both in plan as in elevation. In the words of one reviewer: "They have rightly characterized Pei as combining a classical sense of form with a contemporary mastery of method." In 2000, his biographer Carter Wiseman called him "the most distinguished member of his late-modern generation still practicing." ». At the same time, Pei himself rejected simple dichotomies between architectural styles. He once said: «The debate between modern or postmodern architecture is of no importance. It is a secondary issue. A single building, the style in which it is to be designed and built, is not that important. The important thing, really, is the community. How is it going to affect people's lives?"

Pei's work has been celebrated in the world of architecture. His colleague John Portman once told him, “Just once, I'd like to do something like the East Building of the National Gallery of Art.” His originality didn't always pay off, however; as Pei replied to the successful architect, “Just once, I'd like to make the money you make.” His concepts, moreover, are too individualized and context-dependent to give rise to a design school of their own. Pei refers to his "analytical approach" when he explains the lack of a "Pei school". "For me," he said, "the important distinction is between a stylistic approach to design and an analytical approach that gives due consideration to time, place, and use [...] My analytical approach demands a thorough understanding of these three essential elements. [...] to reach an ideal balance between them".

Awards and distinctions

In the words of his biographer, Pei won "every major award in his art", including the Arnold Brunner Award from the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1963), the gold medal for architecture from the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1979), the AIA Gold Medal (1979), the first Praemium Imperiale for architecture from the Art Association of Japan (1989), the Lifetime Achievement Award of Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, the Edward MacDowell Medal of Arts (1998), and the Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects (2010). In 1983 she was awarded the Pritzker Prize, often called the "Nobel Prize for Architecture". In their statement, the jury said: "Ieoh Ming Pei has given this century some of its most beautiful interior spaces and exterior forms [...] His versatility and skill in the use of materials approach the level of poetry." The award was accompanied by $100,000, which Pei used to create a scholarship for Chinese students to study architecture in the United States, on the condition that they return to China to work. In 1986, he was one of twelve recipients with the Medal of Liberty. When he received the Henry C. Turner Award in 2003 from the National Building Museum, museum board chair Carolyn Brody praised his impact on technical innovation: "His magnificent designs have challenged engineers to devise innovative structural solutions, and his exacting expectations for construction quality have encouraged contractors to meet high standards." In December 1992, President George H. W. Bush awarded Pei the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Personal life

Pei's wife of over seventy years, Eileen Loo, died on June 20, 2014. Together they had three children, T'ing Chung (1946–2003); Chien Chung (1946), known like Didi; and Li Chung (1949), known as Sandi; and a daughter, Liane (1960).T'ing Chung was an urban planner and alumnus of his father's alma mater, MIT, and Harvard. Chieng Chung and Li Chung, who both studied at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, founded Pei Partnership Architects, while Liane is a lawyer. Pei celebrated her 100th birthday on April 26, 2017, and died on borough of Manhattan on May 16, 2019, at the age of 102.

Contenido relacionado

Tarquin the Proud

San Luis Potosi

7th century