Ideology

In the social sciences, an ideology is a normative set of emotions, ideas and collective beliefs that are compatible with each other and are especially referred to human social behavior. Ideologies describe and postulate ways of acting on collective reality, whether on the general system of society or on one or more of its specific systems, such as the economic, social, scientific-technological, political, cultural, moral, religious, environmental or others related to the common good. The Spanish historian José Luis Rodríguez Jiménez has defined ideology as "a universe of values or set of ideas that reflect a conception of the world, codified in a doctrinal body, with the aim of establishing channels of influence and justification of their interests [of the social or political group that supports it]".

Ideologies usually consist of two components: a representation of the system, and an action program. The representation provides its own and particular point of view on the current reality, observing it from a certain perspective composed of emotions, perceptions, beliefs, ideas and reasoning, from which it is analyzed and compared with an alternative real or ideal system, ending in a set of critical and value judgments that propose a point of view superior to the current reality. The action program aims to bring the existing real system as close as possible to the intended ideal system.

Because of its receptivity to change, there are ideologies that seek to preserve the system —conservative—, its radical and sudden transformation —revolutionary—, gradual change —reformist—, or the readoption of a previously existing system —restorative—.

Due to their origin, scope and purpose, ideologies can develop gradually through observation, dialogue, mutual adjustment and consensus on what is considered socially correct, deviant or harmful, or be imposed (even by through violence) by a dominant group especially interested in generating influence, leadership or collective control, regardless of whether this is a social group, an institution, or a political, social, religious or cultural movement or if its purpose is focused on promoting the common good or a private interest.

The concept of ideology differs from that of worldview (Weltanschauung) in that it is projected to an entire civilization or society, in which case it is related to the concept of dominant ideology, when it encompasses all specific systems of society and is shared by a large majority of the population. Due to its collective nature, the concept is rarely restricted to the way of thinking of an isolated or particular individual.

Origin of the term

The term ideology was formulated by Antoine Destutt de Tracy (Mémoire sur la faculté de penser, 1796), and originally denominated the science that studies ideas, their character, origin and the laws that govern them, as well as the relationships with the signs that express them.

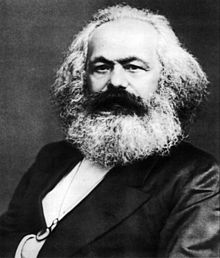

Half a century later, the concept receives its current meaning by being associated with an epistemological perspective, founded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their work The German Ideology (1845-1846), for whom ideology is the set of principles that they explain the world in each society based on their modes of production, relating the practical knowledge necessary for life with the system of social relations. The relationship with reality is very important to maintain these social relationships, and in social systems in which some kind of exploitation occurs, to prevent the oppressed from perceiving their state of oppression. In his famous preface to his book Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy Marx writes:

[...] The whole of these production relations forms the economic structure of society, the real basis on which the legal and political superstructure is built and which corresponds to certain forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the process of political and spiritual social life in general. It is not the consciousness of man that determines his being but, on the contrary, the social being is what determines his consciousness.

Sociology and ideology

We speak of ideology when a specific idea or set of ideas interpreting reality are considered true and are widely shared consciously by a social group in a specific society. Such ideas become a strongly identifying feature, similar to religion, nation, social class, gender, political party, social club, etc., and both small and closed groups are formed as well as sects or larger groups. and open as supporters of a football team.

Externally, it has been more strongly associated with politics, where the clientelism of the parties imposes narrow and closed interests. In its development, it leads to individual behavior leading to a continued false belief, a false thought, and from there to a false social practice. In addition, internally, the members of the ideological group admit or not that a certain individual belongs to the group according to whether or not they share certain common assumptions of basic thoughts.

Ideology intervenes and justifies directing the personal or collective acts of groups or social classes, whose interests it serves. It tries to explain reality in an acceptable and reassuring way, but without criticism, working only by slogans and slogans.

Now what it causes are false beliefs that maintain the previous interpretation or justification as it was in the individual and collective imagination, regardless of the real circumstances. For this reason they usually end up producing a separation between ideas and their practice that is difficult to assume in reality.

The sociology of knowledge is in charge of the study of ideology, whose basic assumption is the human tendency to falsify reality based on interest. Follow your own interest in the ways of seeing the world in the social group to which you belong; ways that vary socially from one human group to another and within different sectors of the same society. It intervenes on personal interest and unites the group where it settles, because it builds a fictitious identity as a way of living and valuing a reality built outside of itself. Hence, in most cases it leads to an overlapping of discourses according to the degree of reality and to the construction of utopias.

In the political arena, and in extreme cases, it leads to repeated lies, mendacity. In general, it is observed that it is easy to go through an excessive interest, focused on false consciousness, towards the image or form of the idea of life interpreted solely in terms of those ideas, in short, towards an ideology that tends to totalitarianism.

The origin of ideologies

The origin of most ideologies is found in a philosophical current when it assumes a very simplified and distorted version, due to false belief, of the original philosophy. In this sense, an insincere character is produced, in general, when an original thought becomes "-ism" (Plato → Platonism; Marx → Marxism; capital → capitalism; anarchy → anarchism; etc.). Its origin is located in the personal field, according to the needs that socially support a certain thought. It separates and dissociates from reality, because it manipulates it in the form of its own interest.

The first philosophers who studied «ideology», the French psychologists (Condillac, Cabanis, Destutt de Tracy), located this need in the «inner self», interpreted in various ways (psychologism and psychophysiologism). The subject is opposed to the exterior, which occurs as an event, since it requires individual reflection. These French philosophers sought to structure a theory on the primitive materialism of sensations and hence their derivation into emotions, passions and feelings. So that from the fact, from the external event or event, psychologically we pass to the internal way of apprehending things and appreciating these categories of personal psychology.

Later, the political commitment of social philosophers (utopian socialists, Saint-Simon, Fourier, Proudhon) placed interest in the needs of social life. The reversal that took place when it spread to the sphere of society was considerable. From the interest of the individual he passed to the interest of the group. This led to the coining of the term "doctrinaire" to refer to "ideologues" in their confrontation with power, which gave the word a pejorative meaning that has not lost today.

After the psychologism of the French, he passed, firstly, to his own philosophical forms and, later, to economic relations. The most elaborate sense of ideology, in the first sense, is that of Hegel and, in the second, of Marx.

Ideology was considered as a «splitting of consciousness», which produces alienation, whether it is considered as merely dialectic of thought, in Hegel's idealism, or material dialectic in Marx's materialism.

In the 20th century, ideology is considered as a problem of social communication. For Frankfurters, especially for Habermas, ideology expresses the violence of domination that distorts communication. This talks about the relationship between knowledge and interest. This produces a distortion that is the consequence of an instrumental reason, such as interested knowledge, and that is responsible for false science and technology as axes of social domination. It is therefore necessary a hermeneutics of emancipation and liberation. In the same way, Marcuse underlines this fact within the social classes, particularly politically within the parties and unions.

Karl Mannheim and Max Scheler frame ideology within the framework of the sociology of knowledge. Knowledge framed within political domination generates such an accumulation of interests that it configures the worldview of social groups. There is no possibility of escaping a well-constructed ideology. Everything revolves around you. Mannheim distinguishes between partial ideology, of a psychological type, and total ideology, of a social type.

Sartre, for his part, introduces a completely different idea of «ideology». For Sartre, ideology is the result of a "creative" thinker, capable of generating a way of seeing reality. On the other hand, Willard van Orman Quine deals with the relationship between external objects, from outside, and internal subjects, from in there In other words, he links ideology to a reasoned way of considering ontology.

At the end of the XX century, however, we entered a time of underestimation of the ideological, hand in hand of conservative ideologies, in such a way that some have proclaimed the decline of idols, such as "The end of ideologies", even proclaiming the triumph of single thought and the "end of history" 3. 4; or the "clash of civilizations".

Ideology as false belief should be studied in terms of its degraded logic, rather than the philosophy from which it is derived. However, it is difficult to understand when and in what terms a philosophy becomes an ideology. Max Weber affirms that philosophies are selected first to be ideologies later, but he does not explain when, how or why. What can be assured is that there is a dialectical relationship, that is, of discourse, between ideas and social needs, and that both are essential to configure an ideology. This is how the interest and needs felt by the social body (or a group thereof) are born; However, they can fail because they do not have clear ideas to support it. Just as there are ideas that can go unnoticed because they are not relevant to social needs, an apparently useful false belief is required to be an ideology.

Marx, in his Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right, states the following:

...It is true that the weapon of criticism cannot substitute for the criticism of weapons, that material power has to be overthrown by material power, but also the theory becomes material power as soon as it takes over the masses. And the theory is capable of seizing the masses when it argues and proves ad hominemand argues and demonstrates ad hominem when it gets radical. To be radical is to attack the problem by the root. And the root, for man, is the man himself...Marx. Contribution to the critique of Hegel's philosophy of law. German francs. 1970. Barcelona. Ed. Martinez-Roca, p 103

Marxist concept of ideology

As historical materialism defines the concept, ideology is part of the superstructure, along with the political system, religion, art, and the legal field. According to the classical interpretation, it is determined by the material conditions of the relations of production or economic and social structure. For Karl Marx, ideologies are bodies of ideas that aspire to universality and the most candid and abstract truth that represent the historical interests of a social class, which are mostly idealist hypotheses. From this perspective, they are forms of "false consciousness", because they only reflect the economic interests and preferences of the "ruling class". Marx gives the example of the division of powers as dominant idea, now proclaimed as an "eternal law" at the time when the crown, the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie compete for power in a country.

The Marxist concept of ideology is usually dated to the works The Holy Family and The German Ideology as a critique of post-Hegelian idealist German philosophy. This critique reached bourgeois political economy in The Poverty of Philosophy and later Capital. Although it can already be seen in Hegel's Critique of the Philosophy of Law with the hypothesis of the "denial of philosophy as philosophy".

The class that has at its disposal the means for material production has, at the same time, the means for spiritual production, which makes the ideas of those who lack the necessary means to produce spiritually. Dominant ideas are nothing but the ideal expression of dominant material relations, the same dominant material relationships conceived as ideas; therefore, the relationships that make a certain class the ruling class, that is, the ideas of its domination. [...]The division of labour [...] is also manifested within the ruling class as a division of spiritual and material work, so that a part of this class is revealed as the one that gives its thinkers (the active conceptual ideologues of that class, that make the creation of the illusion of this class about itself its fundamental power branch), while others adopt before these ideas and illusions a rather passive and receptive attitude, since little active members are

K. Marx and F. Engels (1845) The German ideologyChapter 1, Part III, 1. The ruling class and the dominant consciousness.

Friedrich Engels explains that "the true propelling forces that move it remain unknown to the ideologue. His ideas appear to the ideologue "as a creation, without looking for another more distant and independent source of thought;" for him, this is the very evidence, since for him all acts, insofar as thought serves them as mediator, also have in this their ultimate foundation". These drivers include both obscure subjective interests and the objective economic constellation.

For Engels, morality and religion are examples of ideologies. Morality was always "a class morality; either it justified the rule and the interests of the ruling class, or, as soon as the oppressed class became strong enough, it represented the irritation of the oppressed against that rule and the interests of said oppressed, oriented to the future". The origin of the ideological form of religion is the impotence of man towards nature. The low level of mastery of nature and the dependence on unknown natural events lead to religious-magical practices to compensate for economic, technical and scientific underdevelopment: "These various false ideas about nature, the character of man himself, spirits, magical forces, etc., are always based on economic factors with a negative aspect; the incipient economic development of the prehistoric period has, as a complement, and also partly as a condition, and even as a cause, false ideas about nature".

The development of an ideology follows a certain logic of its own, it develops "by means of imagination". bequeathed to him by his predecessors and from the one he started". However, economics "determines the way in which the pre-existing material of ideas is modified and developed" indirectly, "since it is the political, legal and moral reflexes that exert a direct influence on philosophy to a greater degree".

The role of ideology, according to this Marxist conception of history, is to act as a lubricant to keep social relations fluid, providing the minimum necessary social consensus by justifying the predominance of the ruling classes and political power. On the other hand, Engels also emphasizes the "historical effectiveness" of ideology. The denial of "independent historical development" it does not mean that it cannot be put into the world, once for other causes, ultimately economic, and it can have an effect on its environment, indeed its own cause. Marx recognized that within ideological forms there can be elements of truth..

The existence of revolutionary ideas in a certain period already presupposes the existence of a revolutionary class [...] as a representative of the whole of society, as the whole mass of society, in front of the single class, to the ruling class.Ibid.

This critique has contributed to an academic distrust of notions such as "objectivity", "neutrality", "universality" and the like.

Among the Marxists who have devoted themselves to the study of ideology, or have made significant comments on the subject, are Marx and Engels, Lenin, Kautsky, Lukács, Althusser, Gramsci, Theodor Adorno and, more recently, Slavoj Zizek. Lenin differentiated in What to do? a bourgeois ideology that undermines a socialist ideology by rejecting the mass diffusion of a political class consciousness, making it impossible for an ideology to exist outside classes nor above classes'. Gramsci said that cultural and historical analyzes of the "natural order of things in society" established by the dominant ideology would allow men and women with common sense to intellectually perceive the structures of the bourgeois cultural hegemony.

Although commonly one speaks of a homogeneous theory of ideology in Marxism, linked to the base-superstructure scheme, there are numerous theoretical variations that address this issue. Some analysts of Marxist ideology theory, for example Terry Eagleton, have claimed that different theories on this subject exist in Marx's own writings.

During the Stalinist stage of the USSR, Marxism was reduced to dialectical materialism (or diamat) and a materialist conception of history. These doctrines, codified and hardly questionable, were taught academically, with a section even in the Academy of Sciences. For Western Marxists, and especially for historians of a non-orthodox orientation, which is usually called Marxian, especially in France and England (more or less linked to the historiographic renewal of the mid-century XX which supposed the Annales School), it is impossible to explain history in such a deterministic way. From this point of view, interpretations of ideology are often found in historiography in the sense that the inadequacy of the dominant ideology to new conditions or the emergence of alternative ideologies that compete with it produces an ideological crisis. Thus it is generally accepted that, although from a classical Marxist point of view it sounds heretical, when a dominant ideology does not effectively fulfill its function it increases social tension (class struggle) that contributes to the crisis of one mode of production and its transition to the next..

Ideology as totalitarian critique

Contemporary Australian political philosopher Kenneth Minogue explored the Marxist notion of ideology in his work The Pure Theory of Ideology.

For this author,

- Marxism presupposes by ideology a set of functional ideas of an individual that give universal justification and validity to their interests.

- These interests are mainly understood as the preservation of their economic means of subsistence once adopted; excluding from this category their use or the purpose of consumption, which would return to socially teleological and infrastructural interests.

- Interests in these reduced "material conditions of existence" would be technologically predetermined by the particular social relationship of the individual with its location in the division of labour, whose form would not be modifiable or eligible, that is: its purposes would be necessary instead of contingent.

- These interests have the characteristic of not being common (except with members of the same class) and contrary to the other classes in intrinsically, since their nature is to participate in a dual organic relationship of oppressors-oppressors.

Minogue immediately puts forward a reverse version of this one, turning its basic premises on its head:

- True ideologies are pseudo-revelations that reduce all reality to the existence of groups and genres with predetermined opposite interests.

- Interests that would incarnate themselves a system of oppression (which includes the oppression of functional ideas by others).

- They require blindly interpreting the concept of liberation as the elimination of such kinds of opposite interests.

- And the pragmatic-revolutionary treatment of all functional thinking as systems of ideas (such as ideologies) based on false rationalizations (being the incognosible truth except in the realization of the revolutionary struggle).

The characteristics of this notion of ideology as "critical dogma" stand out particularly in Marxism, and all would have as a particular characteristic their tendency to degenerate into "sociologisms" and "psychologisms" self-contradictory (conspiracy theories in which the forms of social organization would not be historical necessities generated by the dominant social groups and their "ideologies", but conversely, it would be elites who would create society with an ideology that would possible its power; the latter idea that the epistemologist Karl Popper had already denounced as part of a vulgarized and misinterpreted Marxism).

The community of interests between groups is also not only arbitrary (social classes, genders, races), but the very ideological vision of society is actually the ideological society that it generates, since that although it presumes to fight a system of oppression where its elements are organically functional, said oppression would depend only on its concealment (when in fact such concealment would require a pre-existing oppression) and would not be really functional as long as it was not planned (planning that ideology does need to generate).

Because of this, the inter-individual community of interests that the ideological revolutionary boasts of is a useful fiction (Leninism would have sincered this fact by stating that "the bourgeois compete to sell the rope with which the they are going to hang"),[citation needed] but it ends up being a forced reality when ideology comes to power. Minogue thus returns, against the very systemic-classist doctrines (which treat all thought as "ideological"), the accusation of ideological reification in new terms, particularly Marxism, the generation and dependence towards their own interests revolutionaries in an oppressive classless society.

Minogue's thesis was highly influential at the end of the XX century in political and intellectual circles closest to thought demoliberal, conservative and neoconservative, for having given systematicity to the dialectic of Western liberal democracies in their confrontation with Marxist popular democracies throughout the Cold War.

The century of ideologies

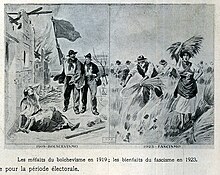

The expression century of ideologies to define the XX century was coined by the philosopher Jean Pierre Faye in 1998. The term ideology, reserved in the XIX century for intellectual debate, became in the XX century the vehicle of great social movements and thought, on the support of great masses that are indoctrinated by the new media, propaganda, violence and repression.

In the interwar period, the political ideologies in conflict were fundamentally fascism and communism, although from the XIX century liberalism survived in its democratic version (against which both define themselves), conservatism, democratic socialism, anarchism and nationalisms. Feminism, pacifism, environmentalism and movements for racial equality and recognition of sexual identity are not strictly political ideologies, with a strong vocation for transforming society. The religious world seems to be absent from most of the new worldviews (in German Weltanschauung) until the end of the XX century, when André Malraux prophesied shortly before he died (1976): the 21st century will be religious or it will not be. It is early to confirm it, but since then fundamentalist Christianity, both Catholic and Protestant, and Islamic fundamentalism have been renewed, both in developed countries (where it goes beyond the interclassism of post-war Christian democracy) and in underdeveloped countries (where it replaces the dominant Third Worldism in the period of decolonization or the liberation theology of the 1970s). The same occurs with Hindu nationalism. Europeanism or the European movement has entered into a clear ideological crisis of which the inability to define values and continental borders in the reformist debates surrounding the Treaty of Lisbon within the European Union.

The weak thought

On the other hand, since the 1980s and 1990s, the concept of ideology suffers a devaluation due to its inadequacy to new emerging intellectual paradigms, such as deconstructivism (Jacques Derrida), or the more generically called postmodernity, which propose a thought weak (Gianni Vattimo), in a certain way a flexible ideology and adaptable to the situations of disconcerting change that occur in the period of the end of the century and of the millennium (especially the fall of the Berlin wall). It is in this cultural context that one understands the formulation of the concept of the third way (Anthony Giddens), an adaptation to globalization and triumphant economic liberalism from social democratic positions (British Labor of Tony Blair or even the presidency of Bill Clinton) that in the practice is an approximation to many conceptions of conservatism.

Derogatory use of the term

Sometimes the concept ideology is used to discredit or disqualify a system of thought, conception of the world or author, indicating that it is ideologized. In principle, an ideology is a well-founded position that proposes a superior point of view and a purposeful action program in the face of a social situation. However, an ideology in the hands of a corrupt dominant group operates as a system of beliefs and rationalizations that reinforces its own position of privilege. The derogatory use of the term understands ideology as a "discourse of social control" that:

- It obeys the interests and group selfishness of its applicants, rather than responding to a search for the common good,

- It has a set of fixed and preset solutions for social problems,

- That's it. dogmaticproposing irrefutable normative premises and which cannot be verified,

- It is accompanied by proselytism, propaganda propaganda propaganda and, in extreme degrees, of indoctrination.

- Account with internal justifications and causes to his control to explain his own failures,

Group egoism

In his dissertation on the human good, Bernard Lonergan details the relationship between corrupted ideology and its postulator's group egoism, declaring: "While the individual egoist has to endure public censure of his way of proceeding, group egoism not only directs development to its own aggrandizement, but also opens a market for the opinions, doctrines and theories that justify its behavior, and will reveal at the same time that the misfortunes of other groups are due to the depravity that corrodes them."

That is, ideology becomes a practical means that enables both the approval of the majorities, their submission, the self-justification of behaviors and the error of opponents, even though the set of ideas does not respond to reality, to the genuine interest of the population or to the common good.

Dogmatism and totalitarianism

According to this pejorative usage, ideologies see the world as something static. It is because of this fact that any ideology sees itself as the repository of ideas that can solve any problem in society, whether present or future. This turns ideology into dogmatism, since it closes itself to the ideas of others as a possible source of solutions to problems that arise on a daily basis, being it the total explanation and last; what some call fierce explanation.

In extreme cases, an ideology can lead to denying the possibility of dissent, giving its postulates as irrefutable truth. Having come to consider ideology as an irrefutable truth, the path to totalitarianism opens, be it political or religious, also called theocracy. Anyone who disagrees becomes a problem for the dominant group, since it goes against the dogmatic truth that the ideology proclaims. Such is the problem posed by dissidents, factions and sects.

Contenido relacionado

Bolivian ethnic groups

Government and politics of Iceland

Politics of Armenia