Iceland

Iceland (Icelandic: Ísland, AFI: ['istlant]), also known as the Republic of Iceland (in Icelandic; Lýðveldið Ísland), is a European island country, whose territory includes the homonymous island and some small islands and adjacent islets in the Atlantic Ocean. Its capital is Reykjavik. It has a population of about 366,425 inhabitants and an area of 103,000 km². Due to its location on the Mid-Atlantic ridge, it is a country with great volcanic and geological activity, a factor that greatly affects the landscape of the territory Icelandic. The interior of the country consists of a plateau characterized by deserts, mountains, glaciers, and glacial rivers that flow to the sea through the lowlands. Thanks to the effects of the Gulf Stream, it has a temperate climate, relative to its latitude, and provides a habitable environment.

The first human settlement in Iceland dates back to the year 874, when, according to the Landnámabók or “Book of Settlement”, the Norwegian leader Ingólfur Arnarson became the first permanent settler on the island Other navigators, such as the Faroese Viking Naddoddr, possible discoverer, visited the island around the year 860 to spend the winter there. However, they never founded a permanent settlement there. Over the following centuries, human groups of Norse and Gaelic origin settled in Iceland. Until the 20th century, the Icelandic population depended on fishing and agriculture. From 1262 to 1397, it was part of the kingdom of Norway and, later, of Denmark. In the 20th century, it gained independence and the Icelandic economy developed rapidly, despite its isolation from the world due to its geographic location.

It has a market economy, with relatively low taxes, compared to other OECD members, maintaining a welfare state that provides universal healthcare and free higher education to its citizens. richest, and is currently classified by the United Nations Organization as the fourth most developed country in the world, in addition to occupying first place in the global peace index.

In 2008, the Icelandic financial system collapsed, triggering a sharp economic contraction and demonstrations that led to earlier parliamentary elections, in which Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir won the post of prime minister. At the same time, the importance of the known as the Icelandic Revolution, a series of protests and citizen organizing movements that, in conjunction with the new government, led to the impeachment of Iceland's previous crisis prime minister, Geir Haarde, two referendums to decide on debt repayment of national banks and a citizen process leading to changes to the Constitution that culminated in a constitutional draft on July 29, 2011, to be debated in Parliament. Since then, the economy has recovered significantly, largely due to to an increase in tourism.

Iceland has a developed and technologically advanced society, whose culture is based on Nordic heritage. Most of the population is of Celtic and Scandinavian origin. The official language is Icelandic, a North Germanic language closely related to Faroese and western Norwegian dialects. The country's cultural heritage includes its traditional cuisine, art, and literature.[citation required]

Etymology

The word "Iceland" derives from the Icelandic Ísland, a word that comes from Old Norse, meaning "land of ice". However, the first name of the country was Snæland< /i> ("land of snow"), coined by the Viking navigator Naddoddr, one of the first settlers of the Faroe Islands. Gardar Svavarsson, one of the first Icelanders, renamed the island Garðarshólmur ("Islets of Gardar").

The final name of Ísland was given by Flóki Vilgerðarson, alluding to the winter landscape of present-day Icelandic territory. Despite the fact that some official documents contemplate Lýðveldið Ísland (Republic of Iceland) as the official name of the country, the current Constitution defines it as simply Ísland (Iceland), without prepending the term "republic".

History

Icelandic Settlement and Commonwealth (874-1262)

One of the theories about the settlement of its current territory states that the first inhabitants of the island arrived in the 8th century and that they were members of a mission of hermit monks, also known as papar, from Ireland or Scotland, although there are no archaeological discoveries to support this hypothesis.

It is presumed that the monks left the island when the Scandinavians arrived, who systematically settled in the period between the years 870 and 930. An article in the journal Skirnir, showing the results of Radiocarbon research suggests the country may have been inhabited since the second half of the VII century.

The first known permanent Norse settler was Ingólfur Arnarson, who built his farm in the area of the present capital in 874. Ingólfur was followed by many other emigrant settlers, largely Norse, and their Irish slaves. By 930, most of the arable land had been taken over and the Alþingi, a legislative and judicial parliament, was founded as the political center of the Icelandic Commonwealth.

The pagan cult began to be abandoned around the year 1000, with the Christianization of the island. The Commonwealth lasted only until 1262, when the political system devised by the original settlers proved unable to cope with the growing power of Icelandic chieftains over the peasant population.

Scandinavian colonization (1262-1814)

Internal and civil strife of the Sturlung era led the country to the signing of the gamli sattmáli (old pact) in 1262, a treaty that placed it under the Norwegian Crown. Possession of Iceland passed to Denmark-Norway at the end of the 14th century, when the kingdoms of Norway, Denmark and Sweden were united in the Kalmar Union.

Barren soils, volcanic eruptions, and an unforgiving climate made life very difficult in a society whose livelihoods depended almost entirely on agriculture. The Black Death swept the town between 1402 and 1404 and again between 1494 and 1495, each time killing about half the inhabitants.

In the mid-16th century 16th, Christian III of Denmark began to impose Lutheranism on all his subjects. The country's last Catholic bishop (before 1968), Jón Arason, was beheaded in 1550 along with two of his sons. Subsequently, the country fully converted to Lutheranism, which has been the dominant denomination ever since.

In the 17th and 18th century, Denmark imposed a series of stricter restrictions on trade, while pirates from England and Algeria ("Turkish hijackings") stormed its shores. A smallpox epidemic in the XVIII killed around a third of the population.

In 1615, clashes took place between the Basques and Icelanders in the vicinity of the Western Fjords region over whaling. For this reason, a law was activated in Iceland that allowed the killing of Basques. This law remained in force until 2015.

In 1783, the eruption of the Laki volcano led to one of the biggest environmental catastrophes in European history. This lasted 8 months, wiped out perhaps 25% of the Icelandic population and produced a cloud (the "Laki mist") which brought a three-year famine across the world, killing approximately 6 millions of people in what became known as “The Hardship in the Mist” (Icelandic: Móðuharðindin), and which is considered one of the most important climatic events with the greatest social repercussions of the last millennium.

Independence Movement (1814-1918)

In 1814, after the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark-Norway was divided into two separate kingdoms by the Treaty of Kiel. Iceland, however, remained a Danish dependency.

During the 19th century, the country's climate continued to deteriorate, prompting mass emigration to the New World, especially towards the province of Manitoba in Canada. About 15,000 people, out of a total population of 70,000, left the country.

In the midst of the migration, however, a new nationalist movement arose, inspired by the romantic and nationalist ideas of continental Europe. Thus, the Icelandic independence movement was born under the leadership of Jón Sigurðsson. In 1874, Denmark granted Iceland a constitution and limited government, which was expanded in 1904.

Kingdom of Iceland (1918-1944)

The Act of Union, an agreement with Denmark signed on December 1, 1918 and valid for 25 years, gave Iceland recognition as a fully sovereign state in a personal union with the King of Denmark. reached Iceland is similar to that of the countries that belong to the British Commonwealth, whose sovereign is the monarch of the United Kingdom.

The Icelandic government took control of its foreign affairs and established an embassy in Copenhagen. However, he requested that Denmark pursue an Icelandic foreign policy towards the other countries. From then on, Danish embassies around the world displayed two coats of arms and two flags: of the Kingdom of Denmark and of Iceland.

During World War II, it joined Denmark in its neutral stance. After Germany occupied Denmark on April 9, 1940, the Althing declared that the Icelandic government should assume the duties of the Danish king and would take charge of its own foreign policy, in addition to other issues previously handled by Denmark at Iceland's request..

A month later, the British Armed Forces invaded Iceland, violating Icelandic neutrality. In 1941, rule of the country passed to the United States so that the United Kingdom could deploy its troops elsewhere.

On December 31, 1943, the Act of Union expired after 25 years. Beginning on May 20, 1944, Icelanders voted in a four-day referendum to determine the future of their personal union with the king of Denmark, and the possible establishment of a republic.

The vote was 97% in favor of ending personal unions and 95% in favor of a new republican constitution. Finally, it officially became a Republic on June 17, 1944, with Sveinn Björnsson as the first president.

Republic of Iceland (1944-present)

In 1946, Allied occupying forces withdrew from Iceland, which became a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization on March 30, 1949, sparking controversy and protests in parts of the country. On May 5, 1951, the nation signed a defense agreement with the United States. US troops returned, remaining there throughout the Cold War, until finally withdrawing on September 30, 2006.

The immediate post-war period was characterized by unprecedented high economic growth, brought about by the industrialization of the fishing industry and the aid offered by the Marshall Plan. The 1970s were marked by the Cod Wars, a series of disputes with the United Kingdom over the extent and rights of the exclusive economic zone. In 1994, the economy diversified and was liberalized when the country joined the Economic Area. European.

Economic development was accompanied by the creation of a welfare state inspired by the Scandinavian model, which promoted raising the standard of living and regulating inequalities. However, an oligarchy continued to rule: fourteen families—a group known as the "Octopus"—made up the country's economic and political elite. They dominated all sectors of the economy: imports, transportation, banking, insurance, fishing, and supplies to the NATO base. Politically, this oligarchy ruled over the Independence Party (PI), which controlled the media. It also determined the appointments of senior officials in the administration, the police and the army. The dominant parties (PI and Center Party) directly managed the local state-owned banks, making it impossible to obtain loans without the approval of the local apparatchik. Thus, a system of patronage relations was generalized.

The economy was liberalized after Iceland's accession to the European Economic Area in 1994, requiring the free movement of capital, goods, services and people. Prime Minister Davíð Oddsson has embarked on a program of selling off state assets and deregulating the labor market. Income and wealth inequalities have widened, exacerbated by tax policies unfavorable to the poorest half of the population.

Between 2003 and 2007, Iceland transformed its economy, hitherto based on the fishing industry, into a nation offering sophisticated financial services. But the alarming signs multiplied rapidly. The country's current account deficit increased from 5% of GDP in 2003 to 20% in 2006, one of the highest levels in the world. In early 2006, Fitch downgraded Iceland's rating from "stable" to "negative". The Icelandic krona lost some of its value, in contrast to the value of banks' debts, which increased. The stock market collapsed and bankruptcies increased, forcing the state to mobilize public finances for the benefit of the private sector. The Danske Bank of Copenhagen then described Iceland as an economy about to explode. Consequently, the country was badly affected by the financial crisis of 2008, which lasted until 2009. This crisis produced the largest emigration from Iceland since 1887.

In early 2009, the numerous citizen protests in the face of the crisis caused the resignation of the government accompanied by a call for elections for the month of April. In these elections, the Social Democratic Alliance and the Left-Green Movement obtained the majority of representation in the chamber. The government, made up of both formations, was chaired by the Social Democratic leader Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir, who assumed power as the new prime minister. In November 2010, a popular assembly of 25 people with no political affiliation was established, which was delegated the responsibility of preparing a proposal to replace the country's Constitution. Iceland's economy stabilized under Sigurðardóttir's rule and grew a 1.6% in 2012.

The Independence Party returned to power in coalition with the Progressive Party in the 2013 elections. In the following years, Iceland experienced a surge in tourism as the country became a popular holiday destination. In 2016, Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson resigned after being implicated in the Panama Papers scandal. Early elections in 2016 resulted in a right-wing coalition government of the Independence Party, Viðreisn and Bright Future. This government fell when Bright Future left the coalition over a scandal involving Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson's father's letter of support for a convicted pedophile. Early elections in October 2017 brought to power a new coalition made up of the Independence Party, the Progressive Party and the Left-Green Movement, led by Katrín Jakobsdóttir.

Government and politics

Iceland is a representative democracy and a parliamentary republic. The modern parliament, Alþingi (translated as “Althing”), was founded in 1845 as an advisory body to the Danish monarch. This parliament was widely seen as a reinstatement of the assembly founded in 930 during the period of the Icelandic Commonwealth, which was suspended in 1799. Consequently, the country "is possibly the world's oldest parliamentary democracy".

It has 63 members, elected for a maximum term of four years. The president is elected by direct vote for a four-year term. The government and local councils are elected separately from the presidential elections every four years.

Since 2016, the President of Iceland is Guðni Thorlacius Jóhannesson, who is the head of state. His position has only ceremonial and diplomatic functions, although he can suppress a law passed by Parliament and submit it to a national referendum. Consequently, the head of government is the prime minister (currently Katrín Jakobsdóttir) who, together with the cabinet, it is responsible for the executive branch. The cabinet is appointed by the president after general parliamentary elections.

The appointment is generally negotiated with the leaders of the political parties with the greatest presence in the Althing, who decide among themselves who should be the members who will form the cabinet and how they should be distributed. Only when party leaders are unable to reach a conclusion within a reasonable time does the president exercise this power and appoint the cabinet himself.

During the history of the republic, the president has only had to use this resource on one occasion when, in 1942, the country's provisional regent, Sveinn Björnsson, appointed a cabinet for himself, since, as provisional regent He had all the powers of a president. In 1944, Sveinn formally became the country's first president.

The true political power that the Office of the President wields is disputed by legal scholars in Iceland; Several provisions of the Constitution appear to give the president some important powers, but other provisions and traditions place him in a different position.

Governments in Iceland have almost always been made up of coalitions between two or more political parties, as neither has won a majority of seats in the Althing on its own. In 1980, Icelanders elected Vigdís Finnbogadóttir as their president, the first woman in the world to be directly elected head of state; she retired from her position in 1996.

Iceland has a cross-sectoral, multi-party political system. The most relevant political parties are the Independence Party (Sjálfstæðisflokkurinn), the Social Democratic Alliance (Samfylkingin) and the Left-Green Movement (Vinstrihreyfingin – grænt framboð ). Other parties that hold seats in the Althing include the Progressive Party (Framsóknarflokkurinn) and The Movement (Hreyfingin). There are other parties at the municipal level, which only compete in elections for local government positions.

Founded in 1778, the Icelandic Police is the organization in charge of applying the law throughout the national territory, with the exception of those places under the jurisdiction of the Icelandic Coast Guard. This police force is administered by the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, in addition to having under its supervision some dependent organizations such as the Icelandic Intelligence Service.

Much of the equipment used by the Icelandic Police is imported: weapons come from Germany, Austria and the United States; the official vehicles are of brands of German, Japanese, British, Korean, Swedish, American and Czech origin.

Foreign Relations and Armed Forces

Iceland maintains diplomatic and trade relations with virtually all nations, but its ties with the Nordic countries, Germany, the United States, Canada, and other North Atlantic Treaty Organization nations are particularly close. Historically and due to constant cultural, economic and linguistic similarities, Iceland is considered politically as one of the Nordic countries, and participates in intergovernmental cooperation through the Nordic Council.

It is also a member of the European Economic Area (EEA), which allows the country access to the internal market of the European Union. However, Iceland is not a member of this organization, but in July 2009, the Althing voted in favor of the application for membership of the European Union. Officials of this body indicated 2011 or 2012 as possible membership dates, although this idea was cancelled. The country is also a member of the United Nations Organization (UN), the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Iceland has no standing army. The United States Air Force maintained four to six interceptors at the Keflavík base until September 30, 2006, when they were withdrawn. Iceland supported the 2003 invasion of Iraq, despite controversy in the country, with the deployment of a Coast Guard team, which was later replaced by members of the Icelandic Crisis Response Unit.

Iceland has also been involved in the ongoing conflict in Afghanistan and the 1999 bombing raid on the former Yugoslavia. Despite the current financial crisis, the first patrol boat was purchased in April 2009, after decades without any such acquisition.

Historically, its main international controversies have arisen over disagreements over fishing rights. British opposition to the extension of the Icelandic exclusive economic zone led to a series of conflicts with the United Kingdom called the "Cod Wars": from 1952 to 1956 as a result of the extension of Iceland's fishing zone from 5.6 7.4 km from the coast; from 1958 to 1961 after a new extension that extended it to 22.2 km; from 1972 to 1973 with a new mark of 92.6 km; and finally in 1975 the last extension up to 370.4 km.

Human Rights

In terms of human rights, regarding membership of the seven bodies of the International Bill of Human Rights, which include the Human Rights Committee (HRC), Iceland has signed or ratified:

Territorial organization

Iceland is divided into regions, constituencies, counties, and municipalities. The first form of organization divides the country into eight regions, which are used mainly for statistical purposes; district courts use an older version of this division to define their jurisdictions. Until 2003, constituencies for parliamentary elections were defined by region, but were changed to just six. The change in this division was made to balance the weight of the different constituencies of the country, since previously a vote in one of the sparsely populated areas had more influence than a vote cast within the capital area. This imbalance was reduced with the change of constituencies, but it still persists.

The twenty-three counties are, for the most part, historical divisions. Currently, the country is divided into 26 magistrates (sýslumenn, singular sýslumaður) that correspond to local governments. Among its tasks are tax collection, civil registration, etc. After a 2007 law enforcement reorganization, which combined police forces from multiple counties into one, about half of the counties were left under this united police force with no local government.

There are seventy-nine municipalities in Iceland, which regulate local government issues such as schools, transportation, and land use. The municipalities are the second administrative level of Iceland, since the electoral districts have no relevance other than for statistical and electoral purposes. Reykjavík is by far the most populous Icelandic municipality, with about four times the population of Kópavogur, the second most populous.

- Divisions of Iceland

Geography

Iceland is located in the Atlantic Ocean south of the Arctic Circle, which passes through the small island of Grímsey. Unlike its neighbor Greenland, it is part of Europe, not North America, although geologically the island lies between the two continental plates.

The closest islands to the country are Greenland (287 km away) and the Faroe Islands (420 km away). The closest distance to mainland Europe is 970 km, towards Norway.

Iceland is the 18th largest island in the world and the second largest in Europe, after Great Britain. The main island has 101,826 km², but the total area of the country amounts to 103,000 km², an area similar to that of Cuba or Guatemala in America. 62.7% is tundra. Around it there are up to 30 smaller islands, including the inhabited island of Grímsey and the Vestman Islands archipelago.

Its rivers flow from the center, where the Highlands are, towards the coast. The longest are the Jökulsá á Fjöllum, to the northeast, and the Þjórsá, to the south. Other river courses are the Hvítá, the Jökulsá á Dal, the Skjálfandafljót, the Blanda and the Fnjóská.

Lakes and glaciers cover 14.3% of the country and only 23% is covered by vegetation. The main glacier is Vatnajökull, the largest in Europe. Others are Langjökull, Hofsjökull, Mýrdalsjökull, Drangajökull, Eyjafjallajökull, Tungnafellsjökull, Þórisjökull, Eiríksjökull and Þrándarjökull.

The largest lakes are Þórisvatn with 88 km² and Þingvallavatn with 82 km². Other important lakes are Blöndulón, Hálslón (which is the reservoir for the Kárahnjúkar hydroelectric power station), Lögurinn, Hágöngulón and Mývatn. Öskjuvatn is the deepest lake in the country, at 217 m deep.

The island itself is composed of basalt and petrified lava with low levels of silica, as well as other rock types such as rhyolites and andesites. Geologically, it is part of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the ridge along the which oceanic crust forms and spreads. In addition, it is located on a hot spot, where magma accumulates below the earth's crust.

The island marks the boundary between the Eurasian Plate and the North American Plate, as it has been created by intense volcanism in the area and along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. All of this translates into high geological activity, which gives rise to more than 200 volcanoes, highlighting Hekla, Eldgjá, Herðubreið and Eldfell, as well as earthquakes and geysers.

On average, every five years it usually suffers a volcanic eruption. Many of these eruptions have had important effects within the country and around the world, such as that of Laki between 1783 and 1784, which caused a famine that caused the death of a quarter of the local population, as well as a cloud of volcanic ash that covered parts of Europe, Asia and Africa.

Between 1963 and 1968, material ejected from the eruption of the Surtsey volcano created a new island that is still among the youngest in the world. The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull eruption forced hundreds of people to abandon their homes and the resulting ash cloud from the eruption caused airspace closures over much of the European continent.

There are many fjords along its 4,970 km coastline, where most major cities and towns are also located. The interior of the island, the Icelandic highlands, is a cold and uninhabitable combination of sand and mountains. The island of Grímsey, just south of the Arctic Circle, contains the country's northernmost population. Iceland has three national parks: Vatnajökull National Park, which is the largest in Europe and home to the glacier of the same name, Snæfellsjökull National Park and Þingvellir National Park.

Climate

The climate of the Icelandic coast is classified as oceanic subpolar, that is, it has cool and short summers, with mild winters (compared to other European countries) and the temperature drops to -10 °C, in the capital. The warm Gulf Stream causes mean annual temperatures higher than those found at similar latitudes in other parts of the world. The coasts of the island are kept without ice during the winter, and despite its proximity to the Arctic this occurs very rarely, the last of which was recorded on the north coast, in 1969.

There are climatic variations between one part of the island and another. In general, the south coast is warmer, wetter and windier than the north coast. The lowlands in the interior and in the north of the island are more arid. Snowfall is more frequent in the north than the south. The interior highlands of Iceland are the coldest area on the entire island.

The highest temperature recorded in the country was 30.5 °C at Teigarhorn, on the southeast coast, on June 22, 1939. On the other hand, the lowest was -38 °C at Grímsstaðir and Möðrudalur, in the northeast, on January 22, 1918. In Reykjavík, the extreme temperatures recorded reached 26.2 °C, on July 30, 2008, and -24.5 °C, on January 21, 1918.

| Month | Ene. | Feb. | Mar. | Open up. | May. | Jun. | Jul. | Ago. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | Annual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average temperature (°C) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 11 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 7.4 |

| Temp. medium (°C) | - 2 | - 2 | - 1 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 0 | - 2 | 2.6 |

| Total precipitation (mm) | 89 | 64 | 62 | 56 | 42 | 42 | 50 | 56 | 67 | 94 | 78 | 79 | 779 |

| Precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 20 | 17 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 18 | 20 | 213 |

| Hours of sun | 31 | 56 | 124 | 150 | 186 | 180 | 186 | 155 | 120 | 61 | 30 | 0 | 1279 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 79 | 75 | 72 | 73 | 67 | 72 | 72 | 71 | 73 | 78 | 80 | 80 | 74.3 |

| [chuckles]required] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

Few plants and animals have migrated to the island or evolved locally since the last ice age, 10,000 years ago. Among its fauna, there are about 1,300 known species of insects, which is quite a low number compared to other countries (more than a million species have been discovered worldwide).

When the first humans arrived on their lands, the only existing mammal was the polar fox, which arrived on the island at the end of the ice age, walking on the frozen sea. There are no native reptiles or amphibians on the island, but there are several species of marine mammals.

Phytogeographically, Iceland belongs to the arctic province of the Circumboreal Region within the Holarctic Kingdom. Approximately three quarters of the island is arid; plant life consists mainly of meadows that are regularly used for livestock.

The most numerous native tree is the northern birch (Betula pubescens), which formerly formed a large forest stretching over much of Iceland, along with the aspen (Populus tremula), the capudre (Sorbus aucuparia), the juniper (Juniperus communis) and other smaller trees.

Permanent human settlements have considerably disturbed the isolated ecosystem of volcanic soils and with a very limited diversity of species.

For centuries, forests were heavily exploited for firewood and lumber. Deforestation caused a critical loss of vegetation cover due to erosion, reducing the ability of the soil to support new life forms.

Today, only a few small birch trees exist among its 59 isolated nature reserves. The planting of new forests has increased the number of trees, but does not compare to the original forests. Some of the planted forests include new foreign species.

Animals

Birds, especially seabirds, are a very important part of Iceland's animal life. During the summer months, the island is chosen as a breeding ground for many species of migratory seabirds such as the puffin, boreal fulmar and kittiwake.

Among the indoor birds, the Whimbrel, the Snowy Grouse and the Red-winged Thrush are easily observable

The only native land mammal is the arctic fox. Other introduced mammals that have become feral include mink, voles, rats, rabbits, and reindeer.

Several species of cetaceans are common in Icelandic waters such as the humpback whale, blue whale, minke whale, and white-beaked dolphin, among others. Commercial whaling is practiced intermittently along with scientific whaling.

Seals populate the coasts and coastal glacial lakes of Iceland, highlighting the common seal.

Polar bears occasionally visit the island, traveling with some ice packs from Greenland. In June 2008, two polar bears were killed in the same month.

Domestic animals of Iceland include sheep, cattle, chickens, goats, the Icelandic horse and the Icelandic shepherd.

Many varieties of fish live in the ocean waters surrounding Iceland and the fishing industry is a major contributor to the economy, accounting for more than half of the country's total exports.

Economy

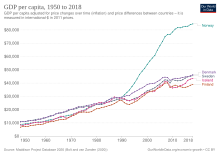

In 2008, Iceland's nominal GDP per capita was the seventh highest in the world ($55,462), and the 14th highest in purchasing power parity terms ($36,769). abundant sources of hydroelectric and geothermal energy, Iceland lacks natural resources; historically its economy is heavily dependent on the fishing industry, which still contributes 40% of export earnings and employs 7% of the workforce.

The economy is vulnerable to declining fish resources and falling world prices for its main exports: fish, marine products, aluminum and ferrosilicon. Despite still depending to a large extent on fishing, this activity is declining in importance, from 90% of total exports it represented in 1960, to the level of 40% it had in 2006.

Until the 20th century, Iceland was a rather poor country. However, its great economic growth led it to rank first in the UN report on the Human Development Index of 2007/2008, and the 14th highest life expectancy in the world with an average of 80,67 years old. Many political parties continue to be against Iceland's accession to the European Union, mainly due to Icelanders' concern about losing control over their economy and natural resources.

The currency of Iceland is the Icelandic Krona (ISK). A large poll, launched on September 11, 2007 by the company Capacent Gallup, showed that 53% of respondents were in favor of adopting the euro, 37% were against and 10% were undecided. During the decade, the Icelandic economy diversified into the manufacturing and service sectors, including software production, biotechnology, and financial services.

Despite the decision to resume commercial whaling in 2006, the tourism sector is expanding with growing trends in ecotourism and whale watching. Agriculture and livestock in Iceland are mainly based on the production of potatoes, vegetables (in greenhouses), dairy products and lamb meat. The financial center of the country is Borgartún, located in the capital, which is home to a large number of companies and three investment banks. The Stock Exchange of Iceland (SIE), was established in 1985.

One of the fundamental pillars of the Icelandic tax system is personal income tax. In 2008, the average rate of this tax was 35.72%, broken down into a state rate of 22.75% and a municipal rate of 12.97%. The corporate tax rate is 18%, one of the lowest in the world. The value added tax also stands out with a rate of 24. %. In 2006 the wealth tax was eliminated. Labor regulations are relatively flexible. Property rights are strong and Iceland is one of the few countries where they are applied to fisheries management. Taxpayers pay different subsidies, similar to what happens in countries with a welfare state, although the expense is less than in most European countries.

According to the OECD, public protection of the agricultural sector is the highest among the countries of this organization, which means an impediment to economic structural change. Furthermore, health care and education spending are relatively poorly spent by OECD standards. The Economic Survey of Iceland 2008 published by this organization highlighted the challenges facing Iceland in currency and macroeconomic policy.

Iceland's economy was badly hit by the economic crisis of 2008-2010, due to the collapse of its banking system and the subsequent economic crisis. Before the failure of the country's three largest banks, Glitnir, Landsbanki and Kaupthing, their combined debt exceeded the national GDP of US$19 billion by more than six times. The Icelandic Financial Supervisory Authority used the permission granted by the Althing to nationalize the three banks.

On October 28, 2008, the Icelandic government raised the interest rate to 18%, a move required to get a loan from the International Monetary Fund. The injection of money by the IMF proved insufficient, but trading in Icelandic krona was eventually restored, with a devaluation taking the Icelandic currency from an exchange rate of 70 ISK per euro to 250 ISK per euro. This devaluation allowed exports to be relaunched, mainly fish and aluminium. The Governor of the Central Bank of Iceland stated that the government also went to Russia for an additional loan of €4 billion.

On January 26, 2009, the coalition government collapsed due to public discontent with the management of the crisis. The following week, a new left-wing government was formed which immediately removed Central Bank Governor Davíð Oddsson and several of his counterparts from other failed private banks. In the April 2009 general election, a left-wing majority he was installed in parliament and Johanna Siguroardottir was elected to head the government.

In 2010, a constituent assembly of 25 members, "ordinary citizens", was established to amend the country's Constitution. In the same year, the government submitted to a referendum the payment of the debt contracted by Icelandic private banks bankrupt with savers in the UK and the Netherlands, but 90% of citizens refused to take it on. Only Icelandic savers affected by the bankruptcy of Icesave bank were compensated.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Iceland has a high rate of automobiles per capita: there are 1.5 vehicles for every inhabitant, making this the main means of transportation. The country has 13,034 km of roads, of which 4,617 km are paved and the 8338 remaining km no. Most of these unpaved roads are found in rural areas and in small towns. Speed limits are 50 km/h in cities, 80 km/h on roads within rural areas, and 90 km/h for highways. There are no railways in Iceland.

Þjóðvegur 1 or Hringvegur, completed in 1974, is the main land route that runs around the entire country, connecting all inhabited parts of the island. The mostly paved road is 1,337 km long and has one lane in each direction, except in the vicinity of large towns and in the Hvalfjörður tunnel, where it has more. It has several bridges, especially in the north and east. this one, which only have one rail and which are made of wood or steel. In recent years, several tunnels have been built, which has speeded up communications.

The main connection center for international transport is the Keflavík International Airport, which serves the demand of Reykjavík and the rest of the country; it is located 48 km west of the capital. Domestic flights to Greenland and the Faroe Islands are controlled from Reykjavik Airport, which is located near the city center. There are 103 registered airports and runways in Iceland; most of them unpaved and located in rural areas. The largest airport is Keflavík, and the largest runway is Geitamelur, a series of four runways about 100 km long, located to the east of Reykjavik, used exclusively for gliders.

Energy

Renewable energy sources, mainly geothermal and hydro, provide all the electricity required in the country, as well as about 80% of all the energy used by Icelanders, with the remaining 20% coming from imported fuels used for transportation and navigation.

Iceland hopes to be energy self-sufficient by 2050. The largest geothermal power plants in the country are Hellisheiði and Nesjavellir, owned by the state-owned company Orkuveita Reykjavíkur, while the Kárahnjúkar hydroelectric power station is the largest in Iceland. its kind. Geothermal energy is produced by the high volcanic activity in the subsoil of the island, which in addition to providing electricity to Icelandic homes, provides heating and free hot water.

Iceland has never produced oil or natural gas. On January 22, 2009, the government announced that it will grant a series of licenses for maritime exploration in search of hydrocarbon reserves in the northeastern region of the country, known as the Dreki Area. Iceland is one of the few countries that have hydrogen stations for fuel cell vehicles.

Media

Iceland is one of the most protectionist countries regarding freedom of expression; the constitution recognizes this right in article 73, and the Icelandic parliament approved in 2010 a law that specifically protects the freedom of expression and information of journalists and writers. Despite the geographical characteristics of the country, the radio, television and internet coverage to the entire population. Iceland ranks thirteenth in the press freedom index compiled by Reporters Without Borders.

Public broadcasting is carried out by the organization Ríkisútvarpið (RÚV), founded in 1930, which operates two radio stations, two television channels and a web portal. The RÚV maintained a monopoly in the audiovisual market until 1986, with the appearance of the first commercial radio (Bylgjan) and private television (Stöð 2). Icelanders pay a specific tax to maintain public media.

The most internationally successful Icelandic production has been the children's series LazyTown (2004-2014), produced in the RÚV studios and broadcast in more than 180 countries thanks to an agreement with Nickelodeon.

As for the written press, the main representatives are the newspapers Morgunblaðið —with national circulation—, Fréttablaðið —focused on Reykjavík— and the web portal Vísir.is. The most widely circulated English-language publications are Iceland Review (founded in 1963) and The Reykjavík Grapevine.

96% of the population has access to the Internet, and more than 75% of the inhabitants are connected to broadband over fiber optics. The main providers are the public company Síminn and the Sýn group. The official domain for Iceland is ".is".

Demographics

Iceland has a population of about 331,000. The original population of the country was of Nordic and Irish origin. This was verified thanks to the study of literary evidence dating from the settlement period, as well as scientific studies in genetics and blood type. One of these studies indicates that the majority of the males who settled in the country were of Nordic origin, while the majority of the females came from Ireland.

Iceland has a large number of complete genealogical records dating back to the late 17th century and fragments going back as far as the time of settlement. The biopharmaceutical company deCODE Genetics created a genealogical database which tries to house information on all the inhabitants of the country. This project, called Íslendingabók ("The Book of Icelanders"), is considered an invaluable tool for genetic disease research, given the relative isolation of the Icelandic population.

From its settlement until the 19th century, Iceland is believed to have had between 40,000 and 60,000 inhabitants. During this time severe winters, volcanic eruptions, and epidemics struck the population several times. Between the years 1500 and 1804, there were thirty-seven years of famine. The first census was carried out in 1703 and He estimated the total population at 50,358. After the destructive eruptions of the Laki volcano in 1783 and 1784, the population dwindled to as low as 40,000. From the mid-19th century, improvements in living conditions led to rapid population growth, from about 60,000 in 1850 to 320,000 in 2008.

Southwest Iceland is the most densely populated region. It is also the location of the Icelandic capital, Reykjavik, the northernmost capital in the world. The largest cities outside of the Reykjavík metropolitan area are Akureyri and Reykjanesbær, although the latter is relatively close to the capital. Of the twenty most populated towns in Iceland, only five exceed 10,000 inhabitants, and of these only the capital exceeds 100,000.

As of December 2007, 33,678 people (13.5% of the total population) living in Iceland were born abroad, including children of Icelandic parents living abroad. 19,000 people (6% of the population) were foreign nationals. The Polish people make up the country's largest immigrant group, and still make up the bulk of the foreign workforce.

In 2010 there were around 8,000 Poles residing, 1,500 of them in Reyðarfjörður, where they make up 75% of the workforce building the Fjarðaál aluminum plant. The increase in immigration was attributed to a shortage of skilled labor due to the boom in the economy, in addition to the removal of restrictions on the movement of people from Eastern European countries when they joined the European Union/European Economic Area in 2004.

Large-scale construction projects in eastern Iceland have also attracted many people whose stay is expected to be temporary. Many Polish immigrants also considered leaving the country in 2008 as a result of the Icelandic financial crisis.

Greenland was first settled by about 500 Icelanders under the leadership of Erik the Red, in the late X. The total population peaked at 5,000, who developed independent institutions before disappearing around 1500. From Greenland, the Norse launched expeditions to settle Vinland, but these attempts to colonize North America were abandoned. soon in the face of hostility from indigenous peoples. Subsequent emigration to the United States and Canada began in the 1870s. Today, Canada is home to more than 88,000 people of Icelandic descent. According to the 2000 census, there are more than 40,000 Americans of Icelandic descent.

Language

The official language of Iceland is Icelandic, a Norse language descended from Old Norse. In fact, it is the language that has changed the least since it evolved from Old Norse, as it has preserved many verb and noun inflections. Furthermore, much of the Icelandic vocabulary that has been created over time is based more on native word roots than loanwords from other languages. It is also the only living language that still uses the runic letter Þ. The closest living language to Icelandic is Faroese. In education, the use and teaching of Icelandic Sign Language is regulated by the National Curriculum.

English is widely used as a second language, as is Danish. Studying both languages is mandatory, as it is enrolled in the National Study Plan. Other commonly spoken languages are German, Norwegian and Swedish. Most learn Danish in a way that is understandable to Norwegian and Swedish speakers; this language is often referred to as skandinavíska ("Scandinavian") by Icelanders.

Instead of using surnames as in all of continental Europe, Icelanders use patronymics. This is placed after the name given to the person, for example: Ólafur Jónsson («Ólafur, son of Jón») or Katrín Karlsdóttir («Katrín, daughter of Karl»). As a consequence, phone books are arranged alphabetically by first name, not patronymic.

Religion

Icelanders are guaranteed religious freedom by the Constitution, although the National Church of Iceland, belonging to Lutheranism, is the state religion. In 2022, about 60.9% of Icelanders belonged to this institution. Of the other religions, 4.6% were members of the Free Lutheran Church of Reykjavík and Hafnarfjörður, 7.8% were agnostics or atheists, 3.9% Catholics, and the remaining 22.8% belonged to other religions.

This last group includes between 20 and 25 Christian denominations. The most widespread non-Christian religion in the country is Ásatrúarfélagið, a neopagan religion inspired by various forms of polytheistic religiosity that predated Christianity. Iceland was the first country in the world to recognize a neopagan religion as a legal religion.

Education

The Icelandic Ministry of Education, Science and Culture is responsible for applying policies and guidelines to schools, as well as publishing the National Curriculum. However, preschool, primary education and the first grades of secondary education are administered and financed by the municipal authorities. Even private schools also receive public funds.

Preschool education, or leikskóli, is the first stage of the Icelandic education system, for all children under the age of six, although it is not compulsory. The current legislation on preschool education was passed in 1994. These schools are responsible for designing their own curriculum, making sure that it eases the transition to compulsory education.

Compulsory education, or grunnskóli, comprises primary and lower secondary education, which are commonly completed at the same institution. By law, all children between the ages of six and sixteen must attend school. The school year lasts nine months, beginning between August 21 and September 1, ending between May 31 and June 10. The minimum number of school days is 170, taking five school days a week. The International Program for Student Assessment, coordinated by the OECD, currently ranks Icelandic secondary education 27th, below the OECD average.

Higher education, or framhaldsskóli, continues after the first years of secondary school. These schools are known as gymnasium. Although it is not compulsory, everyone who has finished secondary education has the right to higher education. This right is established in the Higher Education Act of 1996. The largest institution of higher education in the country is the University of Iceland, whose main campus is located in the center of Reykjavik. Other institutions offering this type of education include the University of Reykjavik, the University of Akureyri, and Bifröst University.

Main towns

| Main locations in Iceland | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locality | Region | Population | Locality | Region | Population | |||||

| 1 | Reikiavik | Höfuðborgarsvæði | 119 | 11 | Seltjarnars | Höfuðborgarsvæði | 4343 | |||

| 2 | Kópavogur | Höfuðborgarsvæði | 31 030 | 12 | Vestmannaeyjar | Suðurland | 4106 | |||

| 3 | Hafnarfjörður | Höfuðborgarsvæði | 26 626 | 13 | Grindavík | Suðurnes | 2914 | |||

| 4 | Akureyri | Norðurland Eystra | 17 530 | 14 | Ísafjörður | Vestfirðir | 2763 | |||

| 5 | Garðabær | Höfuðborgarsvæði | 10 722 | 15 | Alftans | Höfuðborgarsvæði | 2659 | |||

| 6 | Mosfellsbær | Höfuðborgarsvæði | 8600 | 16 | Saudárkrókur | Norðurland Vestra | 2635 | |||

| 7 | Keflavík | Suðurnes | 8551 | 17 | Hveragerði | Suðurland | 2335 | |||

| 8 | Selfos | Suðurland | 6820 | 18 | Húsavík | Norðurland Eystra | 2290 | |||

| 9 | Akranes | Vesturland | 6798 | 19 | Egilsstaðir | Austurland | 2135 | |||

| 10 | Njarðvík | Suðurnes | 4996 | 20 | Borgarnes | Vesturland | 1944 | |||

| Estimate 2010 | ||||||||||

Culture

Icelandic culture has its roots in Nordic traditions and its literature is best known for its sagas and eddas, which were written during the Middle Ages. Icelanders consider independence and self-sufficiency very important; in a survey conducted by the European Commission, more than 85% of Icelanders responded that independence was "very important" contrasting with the European Union average of 53%, 47% of Norwegians and 49% of Danes They also have some traditional beliefs, mainly shared with Norse mythology, which are still valid today; for example, some Icelanders believe in elves, or at least are not willing to rule out their existence.

Iceland is a tolerant country regarding the rights of the LGBT community. In 1996, the Althing passed a law to create civil unions for same-sex couples, encompassing almost all the rights and benefits of marriage. In 2006, by a unanimous vote of the Althing, a series of laws were passed giving same-sex couples the same rights as heterosexual couples in adoption, parenting and assisting in artificial insemination treatments.

On June 11, 2010, the Icelandic parliament amended the Marriage Act, legalizing same-sex marriage. The law entered into force on June 27, 2010.

Literature

The most well-known literary works of Icelandic national literature are the Icelandic sagas, epic tales from the time of their settlement. The most famous include the Njál Saga, which tells of a epic warfare, the Saga of the Greenlanders and the Saga of Erik the Red, which describe the discovery and settlement of Greenland and Vinland (now Newfoundland). Also noteworthy are the Saga of Egil Skallagrímson, that of Laxdoela, that of Grettir, that of Súrssonar and that of Ormstungu as some of the most important works within its genre.

The first translation of the Bible into Icelandic was published in the 16th century. From the 15th century to the XIX the most important compositions were the sacred verses, such as the Psalms of the Passion by Hallgrímur Pétursson, and the rímur, epic poems based on rhymes that present a alliteration.

Originating from the 14th century, rímur were very popular until the XIX, when the development of new literary styles occurred, caused by the influence of the romantic writer Jónas Hallgrímsson. In recent times, several Icelandic-born writers have achieved some international recognition, most notably Halldór Laxness who received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1955.

One of the most international works by one of the fathers of science fiction, Jules Verne, was inspired by the island of Iceland; Journey to the center of the Earth, where the protagonists travel to Snæfellsjökull, a volcano through which they enter to reach the earth's heart.

In the travel literature written in Spanish there are several authors who have felt attracted by the immensity, solitude and solidarity character of the people of Iceland: John Carlin, with Crónicas de Iceland and Jordi Pujolá, who dedicated and set three of his novels in Iceland, highlighting There are no tigers in Iceland.

Art

Art in Iceland began from the settlement of the Icelandic territory, although the beginning of the country's own artistic expressions, such as painting, dance and sculpture, occurred until the XIX, when the movement for independence and autonomy influenced the way Icelandic artists expressed themselves. The roots of the new art movement in Iceland lie in the modernism developed in the rest of Europe and America.

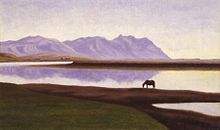

Depictions of the Icelandic landscape in painting is one of the main features of the country's visual arts, with Jóhannes Kjarval being regarded as the foremost representative of Icelandic painting. Other notable painters include Þórarinn Þorláksson, who is recognized as Iceland's first contemporary artist, Ásgrímur Jónsson, Jóhannes Kjarval and Júlíana Sveinsdóttir. The first sculpture to be exhibited in the country was that of the sculptor of Icelandic descent Bertel Thorvaldsen, which was placed in Reykjavík in 1874. Since then, other important sculptors have emerged in Iceland, such as Einars Jónssonar, Ásmundur Sveinsson, Sigurjón Ólafsson, etc.

One of the main characteristics of its performing arts is that amateur performances play a key role on the Icelandic stage, greater than that played in other countries. In 1897 the Reykjavík City Theater opened, one of the first theaters in the country, where the most popular plays in Europe were presented.

To support this art, in 1950 the National Theater was inaugurated, which became an important center for dance and opera; the latter also has the Icelandic Opera building, located in the capital. Currently various groups of actors and dancers are commonly invited to cultural festivals throughout Europe and parts of America.

Icelandic cinema is widely supported by the government, with funds and resources earmarked to promote the development of the national cinematography. The history of cinema in Iceland began in 1906, when Alfred Lind recorded a three-minute documentary on the country. In 1923 Ævintýri Jóns og Gvendar became the first Icelandic film to be shot and by 1948, Milli fjalls og fjöru was the first Icelandic film made entirely in color and with sound. Since then, cinema has slowly developed and currently plays a more active role within the world film industry. The Trapped and The Valhalla Murders series are Icelandic.

Music

Icelandic music is closely related to the music of the other Nordic countries. Currently it stands out for the conservation of the traditions of folk music, pop music, jazz fusion and electronics. Some of its most important musical representatives are the Voces Thules choir, The Sugarcubes band, the Of Monsters and Men band, the Sigur Rós band, the Mezzoforte band (band) and the performers Björk and Emilíana Torrini. The Icelandic national anthem is "Lofsöngur" ("Prayer Song"), with lyrics by Matthias Jochumsson and music by Sveinbjörn Sveinbjörnsson.

Icelandic traditional music has strong religious influences. Icelandic composer Hallgrímur Pétursson wrote many hymns for the Protestant Church during the 17th century. Icelandic music was modernized in the 19th century, when Magnús Stephensen introduced the organ and harmonium to the country. The rímur poems also evolved to be accompanied by music, with Sigurður Breiðfjörð being the most notable rímur poet of the century XIX. In 1929, the poems were modernized with the creation of the Iðunn organization.

Contemporary music from Iceland is represented by a number of artists spanning a variety of genres, from pop rock groups like Bang Gang, Quarashi, Of Monsters and Men, Amiina and Kaleo, to balladists like Bubbi Morthens, Megas and Björgvin Halldórsson.

Independent music is very strong in the Icelandic music market, with bands like múm, Sigur Rós and singers like Emilíana Torrini and Mugison achieving international recognition. However, singer Björk is the one who is often mentioned as the most important of its musical artists. The main music festival in the country is Iceland Airwaves, an annual event where Icelandic artists along with foreign guests appear in all the clubs in the capital for a week. Similarly, metal also has an important place in the independent Icelandic music scene, being the third country in Europe with the most formations of this genre; counting with groups such as Sólstafir or Skálmöld, with wide worldwide recognition, and the internationalized Icelandic black metal scene, exemplified by artists such as Svartidauði, Naðra, Sinmara or Misþyrming.

Although it has never won, Iceland has participated every year in the Eurovision Song Contest since 1986, being one of the countries that most faithfully follows the contest, reaching screen quotas close to 100% share annually.

In 2011, the Harpa concert and conference center opened in Reykjavik, which is home to the Icelandic Symphony Orchestra and the Icelandic Opera.

Parties

| Date | Holiday | Local name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 January | New Year | Nýársdagur | |

| 1 March | Beer Day | Bjórdagura | End of dry law. |

| March/April | Holy Thursday | Skírdagur | Thursday before Easter. |

| March/April | Good Friday | Föstudagurinn langi | Friday before Easter. |

| March/April | Easter Monday | Annar í paskum | Monday after Easter. |

| April | First summer day | Sumardagurinn fyrsti | First Thursday after April 18th. |

| 1 May | Work day | Labor Day | |

| May | Ascension Day | Uppstigningardagurt | Six weeks after Holy Thursday. |

| May | Monday of Pentecost | Annar í hvítasunnu | Celebrated Monday after Pentecost Sunday, six weeks after Easter Monday. |

| 17 June | National Day | CHEDULE: | |

| August | Trade Day | Dagur Trade | First Monday of August. |

| 24 December | Christmas Eve | Aðfangadagur | |

| 25 December | Christmas | Jóladagur | |

| 26 December | Boxing Day | Annar í jólum | |

| 31 December | New Year's Eve | Gamlárskvöld |

Gastronomy

Because for many years fishing was the main engine of the country's economy, the consumption of marine products is the main base of most of the dishes within its gastronomy. In addition to fish and shellfish, the The main meat consumed is lamb, followed by horse, cow and reindeer.

Traditional meals include ingredients such as skyr, which is a dairy product made from yoghurt, marinated ram's scrotum, marinated shark, roasted lamb's heads and some typical blood sausages from its gastronomy called slátur. Some of the best known Icelandic dishes are gravlax, hákarl and kleina. Iceland's national drink is brennivín, an alcoholic beverage made from fermented potato pulp.

Currently, the Icelandic diet is very diverse, since in addition to traditional dishes, recipes from various cuisines of the world are consumed. As in other Western societies, fast food consumption is widely popular.

Sports

- Urvalsdeild Karla

- 1. deild karla

- 2. deild karla

- 3. deild karla

The Icelandic team that has won the most first division is KR Reykiavík.

Sports are an important part of Icelandic culture. Its main traditional sport is glima, a fighting style estimated to have its origins in the Middle Ages. The most popular sports are soccer, athletics, handball, and basketball. Handball is frequently described as the national sport; the Icelandic team has had a constant participation in the Olympic Games and world championships.

In 2016, the Icelandic national soccer team qualified for that year's Euro Cup, which was a historic achievement, since until then they had never participated in high-level international championships. He achieved two draws with the teams of Portugal and Hungary and a victory against Austria, which allowed him to advance to the second round and face the England team, which he defeated 2-1 on June 27, which allowed them to advance to the quarterfinal phase and face France in Saint-Denis on July 3, with the final result of 5-2 favorable to the host team.

After a 2-0 victory over Kosovo in the European qualifiers, they secured a place in the soccer World Cup organized in Russia, marking a historic milestone for the sport in this country.

According to the FIFA world rankings, the Icelandic women's national soccer team is one of the top twenty teams in the world.

Its climate and geography create the optimal conditions for winter and mountain sports, with mountaineering and hiking being the most practiced by the general public. The country is also an ideal place for skiing, with telemark being the most practiced variety. Its oldest sporting association is the Reykjavik Shooting Association, founded in 1867. Rifle shooting became very popular during the 19th century< /span> and was strongly supported by politicians and independence figures. Today it is still very popular and is widely practiced throughout the country.

Several Icelandic athletes have been successful in other sports whose tradition in the country is not so old. For example, in chess the participation of Hannes Stefansson, Helgi Ólafsson and Friðrik Ólafsson (who would become president of the International Chess Federation) stands out. In strongman, Jón Páll Sigmarsson and Magnús Ver Magnússon won the title of "The strongest man in the world" on more than one occasion.

Contenido relacionado

Incunabula

Emerald

Anaximander