Ibero-Romance languages

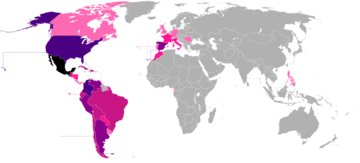

The Ibero-Romance languages are a subgroup of Romance languages that possibly form a phylogenetic subgroup within the Romance family. The Ibero-Romance languages developed in territories occupied by the Romans around the year 415, that is, the Iberian Peninsula, the south of Gaul and the north of the Maghreb and their subsequent conquests.

Languages universally considered within the Ibero-Romance group are Galician-Portuguese (and its modern descendants), Astur-Leonese, Spanish or Castilian and Navarro-Aragonese. Some authors also include the Occitan-Romance languages. All these languages form a geolectal continuum with high intelligibility between adjacent languages.

General classification

The Ibero-Romance languages are a conventional grouping of the Romance languages, although many authors use the term in a geographical and not necessarily a phylogenetic sense. Phylogenetically, there are discrepancies as to whether which languages should be considered within the Ibero-Romance group, since, for example, some authors consider that the Ibero-Eastern languages, also called Occitan-Romance languages, could be more closely related to the Gallo-Romance languages than to the Western Iberian languages (nuclear iberoromance). And the position of Aragonese within the Romance languages of the Iberian Peninsula also causes discrepancies.

A common conventional geographic grouping is as follows:

- Western iberorromance languages (nuclear immunity)

- Oriental iberorromance languages (Occitanus and Aragonese)

- Mozárabe

In what follows, the conventional sign † will be used for extinct languages.

Western Ibero-romance (nuclear)

Western Ibero-Romance presents a number of defining grammatical and phonological features that are absent in the so-called Eastern Ibero-Romance, which in turn presents characteristics in common with Gallo-Romance or Gallo-Italic but not present in Western Ibero-Romance languages. Some authors consider that the Ibero-Romance languages encompass only the western and nuclear group and that the so-called "Oriental Ibero-Romance" It really constitutes a separate phylogenetic group with intermediate characteristics between Ibero-Romance and Gallo-Romance.

The western Ibero-Romance languages (Ibero-Western Group) are:

- Asturleon:

- Asturiano

- Leon

- Mirandés

- You speak of transition between Spanish and Asturleon:

- Extremeño or Altoextremeño

- Cantabri or Montañes

- Spanish or Spanish

- Dialectos del español

- Judeo-Spanish, Sefardí or Ladino

- Judesmo and Haketiyya

- Subgroup galaico-Portuguese

- Galaicoportugués (†)

- Gallego

- Fala

- Portuguese

- Dialectos of Portuguese

- Judeoportugués (†)

Eastern Ibero-Romance (Occitan-Romance languages)

The Occitan-Romance languages, sometimes called Eastern Ibero-Romance, form a separate group and their inclusion within the Ibero-Romance languages is problematic, since they do not share the main characteristics of the languages themselves. It is also discussed whether it is possible to consider them close to the Gallo-Romance, Gallo-Italic or Retorromance languages.

According to Ethnologue the Eastern Ibero-Romance languages are:

- Occitan

- Northern: Auvernés, lemosín, viveroalpino

- Southeast: languedoc, Provencal

- Gascon: orange, bean, moustre

- Shuadit (judeo-provenzal) (†)

- Catalan/valencian

- Eastern: Central, North-East, War, Balearic (Malloquin, Menorcan, Ibienco),

- Western: northwest, tortosino, valenciano (apitxat, northern, southern, alicantino, castellonense)

- Judeo-catalan (†)

Pyrenean-Mozarabic Iberorromance

The Ethnologue classification includes a doubtful group of Romance languages of the Iberian Peninsula, made up of Navarro-Aragonese and Mozarabic: the Pyrenean-Mozarabic Group, although many Specialists consider that this division is not a valid group, nor do they find many arguments to postulate a special relationship between the Aragonese and the Mozarabic.

- Navarroaragonés (†):

- Riojano precastellano (†)

- Romance navarro (†)

- Aragonés

- Western Aragonese: Aragüesino, Ansotano, Cheso, Aisino

- Aragonés central: Belsetano, Aragonés del valle de Vió, Panticuto

- Eastern Aragonese: Patués or Benasqués

- Southern Aragonese or Somontanese

- Judeoaragones (†)

- Mozárabe (†)

The Pyrenean-Mozarabic group is usually classified in various ways, and there is no global consensus on its parentage. The most accepted theories are:

- 1- The one that classifies it as a third group within the Iberian languages.

- 2- the one that places it as a separate group of the iberorromance group, even outside the galo-ibérico group, and within the italo-Western group, which also forms part of the so-called Gallo-ibéric languages. This option is basically followed by Ethnologue.

Transitional Ibero-Romance varieties

Given the close proximity of the Ibero-Romance languages throughout the Iberian Peninsula (and some areas of South America), there are areas where mixed languages or transitional linguistic varieties are spoken that present mixed characteristics with those of the adjacent Ibero-Romance languages. These mixed languages are:

- The castrapo, which is the name given in Galicia (Spain) to a popular Spanish variant spoken in the autonomous community, characterized by the use of vocabulary and expressions taken from the Galician language that do not exist in Spanish. It is considered socially vulgar. It is common in Galician cities.

- The amestau, or variant of asturian, is characterized by a lexical, phonetic and syntactic chaplainization, being much more accused in the first two. For some it is a talk of transition between the Asturian and the Spanish, although many others defend that, because of their syntactic structures, it is a variant of the Asturian (or of the Asturian). low-class asturian).

- The barranqueño (to the foot of Barrancos) is a mixed language spoken in the Portuguese town of Barrancos. It is a dialect whose base is the alentejano Portuguese with a strong influence of the popular Spanish of Andalusia and the Baja Extremadura (see below), especially lexicographics, phonetics and morphological. These elements are sometimes strange and even discordant for a Portuguese-based dialect.

- The portuñol, portunhol, portanhol is the mixture of Portuguese and Spanish languages. It is given among the speakers of the linguistic regions bordering Spanish and Portuguese, especially on the Uruguayan-Brazilian border.

- The river It is a dialect of transition between the Aragonese language and the Catalan language, which is spoken in the extension that since the Middle Ages occupied the Old County of Ribagorza, that is, from the towns of Benasque and Aneto to the southern border of the current region of La Litera and having by western limit the old County of Sobrarbe and oriental the County of Pallars and the lower zone of the river Noguera In the centuryXVI the capital of the County was in Benabarre, and the County belonged from medieval times to the Dukes of Villahermosa and by inheritance, the last Count of Ribagorza was King Philip II.

Discussed Varieties

- The eonaviego or Galician-asturian, west of Asturias or Galician of Asturias (or simply) skirt for your speakers) is a set of words (or falas) whose linguistic domain extends, as its name indicates, in the Asturian zone between the Eo and Navia rivers, although its area of influence also covers more eastern areas than the aforementioned Navia River. Your adscription to the galaxy-Portuguese group is discussed or if it is a transition talk. This territory is known as Eo-Navia land (a territory that does not coincide with the Eo-Navia region). It should be pointed out that its formation does not serve the same canons as that of other mixed or transition languages, since its origin is purely Galician or, in any case, Galaicoportugués; and similarities with the Western Asturian are due to political, social, border and geographical causes. That is why you should always include eonaviego within the Galician language and the galaxy-Portuguese subgroup.

Ibero-Romance Creoles

In many areas of Africa and America, particularly in areas where historically there was an important slave trade and therefore contact with speakers of very different languages, pidgins developed as a means of exchange, which gave gave rise to numerous Spanish and Portuguese-based creole languages:

- Spanish lexical base criollos

- Chabacano

- Palenquero

- Portuguese lexical base criollos:

- Caboverdiano

- Lunguyê

- Angolar

- Forro

- Kriol

- Macaense

- Mixed criollos:

- Papiamento (≈) (for some it is a Spanish-based cryollo, although others consider it Portuguese-based): Papiamento de Aruba, Papiamento de Bonaire, Papiamento de Curacao

- Annabonense or Fá d'Ambô, annobonense or annobonés (also called) Fla d'Ambu and Falar de Ano Bom) is a mixture of a Portuguese Creole, the lining and Spanish spoken on the island of Annobón, Equatorial Guinea.

Cladistic tree

The ASJP systematic comparison project based on lexical similarity measured as the Levenshtein distance of a list of cognates has constructed cladistic trees that give a reasonable approximation to the phylogenetic relatedness of numerous families. In the case of the Ibero-Romance languages mentioned above, the cladistic tree has the form:

| Romance |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main characteristics of the Ibero-Romance languages

- They keep the Latin vowels at the end of the words in contrast to the galorromances, galoitálica and re-romances. Occitan-Romantic languages also lose Latin final vowels.

- They lose the Latin adverb forms Ibi and Inde present in the other Romantic languages. The West-Roman languages and the Aragonese (as well as the medieval Spanish), conserve these adverb forms in their lexicon.

- The infinitive form it with a final (r) and are not lost in contrast to the Galician languages and re-Romans. In the Galloromance and Occitanus (Caltan and Occitan) languages they are preserved in writing but are not pronounced.

- Evolution of Latin groups (cl, fl, pl) to /./ /t savings/. In the Gallo-Roman languages, re-Romances, the West Bank and the Aragonese, these groups are preserved (clau in Aragonese and Catalan, clef in French; flloves in Aragonese, West and Catalan, flamme in French; pl♪ in Aragon, plòure in the West, plOure in Catalan, pleuvoir in French).

- Evolution of Latin groups (ci, ti, ce, te) a (/θ/, /z/ /s/).

- Diptongation before (e, o) brief Latinas, This feature is present in all Iberian languages except for the galaxy-Portuguese and Catalan, for example (ventum - vieStop it.uente and aragonés folia - fuella). This phenomenon also occurs, although to a lesser extent, in the West (ventum - vent, folia - fuèlha).

- Betacism: There is no distinction between b and v excepting the Portuguese where the distinction is maintained. In the West-Roman languages, this distinction persists in the culta standard, in some dialects (valencian, balear, most of the West's dialects, with the notable exception of the gascony).

- Smile or lose the deaf occlusive Latin intervocálicas /p, t, k/ for example (sapere - saber, potere - poder, formica - hormig(a). This is a characteristic of western romance languages.

- They form the plurals with (s), as well as all western Roman languages.

- Change of latin (f) to (h). This phenomenon occurred in Castilian, Extremadura, Cantabri and Eastern Asturian by the influence of the Basque language. This feature is also shared with the gascon West. On the other hand, this phenomenon, like in the galorromance languages, does not occur in the rest of Occitania and Catalan (formica - fourmi in French, formiga in the West and Catalan).

Linguistic description

There are various phonetic innovations common to Ibero-Romance languages:

- Most of the iberorromance languages keep the final vowels Latin /-e, -o/ in male names, in front of what happens in Occitanorrománico and galorrománico, for example: Spanish night, Portuguese noite in front of balear/catalán/valenciano nit, French nuitall of them derived from the form *noite common to proto-iberorromance, galorromance and occitanorromance.

- Palatalization of the group -ct-: Portuguese Oito, Spanish eight. This feature is also shared by the Occitanus and the galorenic, but not the central and southern italorromance. otto and Eastern romance octo.

Phonology

The consonant inventory of Proto-Ibero-Romance coincides with the inventories of Medieval Spanish and Medieval Portuguese:

the Alveolar shovel-

Alveolarensure that Occlusive ♪ ♪ d ♪k ♪ Africada *t spins *d spinz ( Fridge *f/ * *v/β ♪ * devoted * Nasal ♪ ♪ * Lateral ♪ * Vibrante ¶¶

This system is almost identical to Standard Italian (except for the fact that Italian lacks /*ʒ/ and the opposition /*ɾ/-/*r/). The phoneme /*t͡ʃ/ is complicated because, although it appears in both Portuguese and Spanish, in both languages it comes from from different Latin groups, so it is possible that in Proto-Ibero-Romance this phoneme did not exist as such and its presence is due only to later developments. It is postulated here because occasionally in Spanish there is /t͡ʃ/ from PL- latino (AMPLU port. and esp. ancho, P(O)LOPPU > esp. chopo, port. choupo).

As for later evolutions:

- Africans /*t nets, *d ringz, *t backup, *d circle/ desafrican in Portuguese and dan /s, z, ・, ⋅/, while in asturleonian and medium Spanish there are ensordecimientos /*t savings, *d redundaz/ ▪ /s// (and later ▪ /θ/), /*t implied, *// ▪ /t implied/.

- the fricatives ♪ remain in Portuguese, but they lose the contrast of sonority is average Spanish and asturleonés giving only /s, ≤. In modern Spanish additional change / ▪ /x/ (secure/own).

- the cold lips /*f-,, *v-β/ remain in Portuguese as f, vwhile in Spanish /*f-// Come on. /h/ (vocalizing) and/or maintained as /f/ (bearing) /: front, fry or [wV]: source, fire). From the centuryXV the /h/ of Spanish falls in most of the dialects and disappears.

- the fonema /*// in Portuguese and Galician in many contexts passes to /t implied/ (Key ▪ chave), an African similar to that given in some varieties of asturleonés (Western Austrians) ♪ ▪ obu 'lobo').

The reconstructed vowel inventory for the stressed syllable is made up of seven vowels /*i, *e, *ɛ, * a, *ɔ, *o, *u/.

Phonetic changes

The vowel system in the stressed syllable has been better preserved in the Galician-Portuguese varieties than in any other Ibero-Romance (Oriental) area, in these varieties the original four degrees of opening (closed, semi-closed, semi-open, open) continue to be maintained.. In Spanish, Astur-Leonese and Aragonese, the degrees of opening have been reduced by one unit and the number of distinctive vowels has been reduced to five /i, e, a, o, u/ (in Catalan the same vowels are still preserved as in Galician). In Valencian, there are seven vowels: open (à-è-ò) and closed (é-í-ó-ú). Medieval Spanish shows different reflexes for semi-closed and semi-open vowels in stressed syllables, the former are maintained but the latter are diphthong: /* ɛ/ > [je] and /*ɔ/ > [we], while /*e/ > [e] and /*o/ > [o]. In the unstressed system, both Portuguese and Balearic/Catalan/Valencian show allophonic variation.

The main differences in the consonantal system are restricted to the affricates and fricatives:

- So the non-African obstructors and nasals /*p, *b, *m; *t, *d, *n; * remain in all languages, as well as the two liquids /*l, * eclipse/.

- The Portuguese has lost the contrast between African and French ♪ ▪ ♪.

- In Spanish, asturleonian and Aragonese the contrast between deaf and sound was lost in the African and fricative series: ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪♪♪♪♪ ♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪♪ ▪ /*s;; *. Subsequently /*s// ▪ /*θ/ in northern Spanish, Asturleonian and Aragonese (although in Andalusia, the Canary Islands and the Americas /*s// ▪ /s/). All over the Spanish domino as well / he/she/she/.

- Other minor changes are that the Portuguese changed the rhotic /*r/

- In Spanish, asturleonian and Aragonese /*β/ .

- In much of the Spanish domain lleism prevailed /*// ▪ ///.

- Ante /a, o, u/ /*f/ ▪ /h/ ▪ Øeven though it stood before [we, θV] and occasionally also [je] (fever)

The following table summarizes the changes between proto-iberorromance and modern languages:

| PROTO- IBERORROMANCE | Portuguese | Gallego | Asturleon | Spanish | Aragonés | Balear/Catalan/Valenciano |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p b m, t dn,, l, ɾ | (no change) | |||||

| s | s, θ | θ | θ, s | θ | s | |

| z | z | |||||

| s | s | s | s | s | s | s |

| z | z | z | ||||

| MIN | ,, | ,, | ||||

| ♫ | MIN | x | ,, | |||

| MIN | MIN | MIN | MIN | |||

| ♫ | ♫ | ・, | ♫ | ,, Ø, x | ♫ | |

| f// | f | f | f, h | f, Ø | f | f |

| v/β | v | b | b | b | b | b, v |

| r | r | r | r | r | r | |

| ,,,, x | ||||||

Lexical comparison

Comparative table between Latin and Romance languages from the Iberian Peninsula.

| Latin | Western(Galaicoporgugués) | Centro-Occidental(Asturleonés) | Central(Spanish) | Mozárabe | Central-Pirenaico(Navarroaragones) | Eastern(Occitanorromance) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portuguese | Galego | Eonaviego | Asturiano | Leon | Mirandés | Extreme. | Castellano | Manchego | Murcia | Andaluz (EPA)/(PAO) | Mozárabe | Aragonés | Catalan | Aranés (West) | |

| KEY | chave | chave | chave | Key | chave | chave | llavi | Key | peave | llabe Yabe | Yabe | clabe | clau | clau | clau |

| NOCTE(M) | noite | noite | noite | nueche | nueite/nuoite | nuôite | nuechi | night | norche | nonche | noxe | Nohte | nueit, nuet, nit | nit | nueit net |

| CANTARE | sing | sing | sing | sing | sing | sing | cantal | sing | cantal | Cantaa (sing cantal) | cantâh/cantâ | sing | sing | sing | sing |

| CAPRA | goat | goat | goat | goat | goat | goat | crabra | goat | crabra crabro | goat craba | goat | capra | craba | goat | craba |

| FLAMA | chama | chama | chama | flame | flame | lhama | flame | flame | flame | flame/yama | yama | flama | flama | flama | flama |

| LINGUA | Line | lingua | lingua/ Ilingua | Ilingua | ingua | Idengua | Luenga | tongue | Langua | Filled. yen. | tongue | lingua | Luenga | Filled. | Filled. yen. |

| PLORO | ♪ | ♪ | ♪ | cry | cry | Time | Weep | cry | cry | cry/yor | yorâh/yorâ | plorar | plorar | plorar | plorar |

| PLATEA | praça | praza | praza | Square | plaça | praza | praça | Square | praza | Square praza | plaça/plaza | placha | plaça | plaça | plaça |

| PETRAM | pedra | pedra | pedra | stone | stone | stone | pie | stone | stone | stone | stone/stone | Bedra | stone | pedra | pedra |

| PONTE(M) | Put on. | Put on. | position | Put on. | Put on. | Put on. | puenti | Bridge | Bridge | Bridge Potential | Bridge | bont | puent | pont | pont pònt |

| VITAM | life | life | life | life | life | bida | via | life | life | life | Bía | vita | life | life | life |

| SAPERE | to know | to know | to know | to know | I know. | to know | knows. | to know | to know | know/sabel | çabêh/sabê | xaper | to know | to know | to know |

| FORMICAM | form | form | form | form | form | form | Hormiga | Hormiga | Hormiga | Hormiga | ant/ormiga | formica | liniga | form | form |

| CENTUM | cem | Census | Census | One hundred | Census | Census | One hundred | One hundred | One hundred | One hundred | çien/zien | red tape | One hundred | cent | cent |

| ECCLESIA | Igreja | igrexa | eigresia | ilesia | eigreixa | Igreja | igresia | church | igresia | ilesia inlesia | igleçia/ilesia | English | lésia | English | glèisa |

| HOSPITALE(M) | hospital | hospital | hospital | hospital | hospital | hospital | ohpitá | hospital | hojpital Horpital | öppitá ëppitá | ôppitâh/ohpitâ | hospital | hospital | hospital | espitau |

| CASEUS Lat. V. FORMATICU(M) | I demand | queixo | queixo | That they | queisu | I demand | That they | cheese | cheese | cheese | queço/queso | case | cheese/formage | formatge | hormatge hromatge |

| CALLIS Lat. V. | Rua | Rúa | Caleya | cai | Rua cai | rue | Shut up. | Street | Caye | career Street Caye | Caye | Shut up. | career | carrer | carrèr |

Numerals

The numerals in different Ibero-Romance and Occitan-Romance varieties are:

GLOSA Galaicoportugués Asturleon Spanish Mozárabe Occitanorromance Portuguese Gallego Asturleon Estremeñu Castellano Andaluz (PAO) Aragonés proto-Oc Catalan '1' [ chuckles ]

Um... / Uma[ŭ] / ['u.️]

One / unha*[un] / ['u.nu]

a/['un(u)] / ['una]

a(u) / One*['un(o)] / ['un.a]

One / One*['un(o)] / ['un.a]

a / One*[un] / ['u.na]

One/

اون / انا[un] / ['u.na]

One / One*[yn] / *['y.na]

a/a[un] / ['u.nambi]

One / One'2' [doj~ dojs] / ['du.]・ ~ 'du.]s]

dois / Duas[dows] / ['du.as]

dous / Duas[two ~ dows]

Two.[doh]

Two.[two]

Two.[doh ~ d]h]

doh*[two] / ['du.as]

2 / duas

دوس / دواس[two]

Two.*[dus] / *['du.as]

2 / duas[two] / ['du.

Two. / dues'3' [t margins]

três[t margins]

Three.[t margins]

Three.[t margineh]

Three.[t margins]

Three.[t margineh ~ tr discipleh]

treh*[t rays]

Three.

ترس[t margins]

Three.*[t rays]

Three.[t/25070/s]

Three.'4' [kwat flashu]

quatro[kat rays]

Catro[kwat flashu]

Cuatru[kwat flashu]

Cuatru[kwat chanting]

Four['kwat eclipseo]

Four*[kwator ~ kwater]

quator ~ quater

كواتر[kwat flasho ~ kwat radiation]

quatro ~ quatre*[k(w)at margine]

quatre[kwat chanting]

quatre'5' [s]ku]

Five[θi paceko ~ sigil]

Five[θiŭku]

cincu[sigilku]

cincu[θigilko]

Five['θiŭko ~ 'sigilko]

zinc*[t implied]

Five

جنك[θiŭko ~ θiŭk]

Five*[sigilk]

cinc[sigilk]

cinc'6' [sejь ~ sejs]

Six[sejs]

Six[sejs]

Six[sejh]

Six[sejs]

Six[sejh] / [sæjh]

seih / saih*[laughter]

xieis

شيس[sjejs] ~ [sejs]

♪ Sieis ♪*[sjejs]

Yes[sis]

Yeah.'7' [straint] ~ s becoming]

sete[straining]

sete[sighs]

Seven[sjeti]

sieti[sighs]

Seven['sjete ~ 'θjete'

Seven*[laughter]

xiet

شيت[sjet ~ set]

siet ~ set*[sengagement]

sèt[straining]

set'8' [ojtu]

Oito[bleep]

Oito♪[ojtu ~ o]u]

oitu ~ ochu[o]u]

ochu[o]o]

eight['ogilo ~ 'o]o]

ox♪[wehto ~ weht]

uehto ~ ueht

وهت[weito ~ weit]

ueito ~ ueit*[weit]

ueit[vuit ~ vulit ~ uit]

vuit / huit'9' [n]v] ~ n]vi]

No.[n]βe]

No.[nweβe]

Nine[nweβi]

nuevi[nweβe]

Nine['nweβe]

nuebe♪[n]βe]

No.

نوبا[nweu ~ now]

nueu ~ nou♪[n]w]

No[n]w]

No.'10' [d transformation ~ d transformations]

dez[d transformation ~ d transformations]

dez[djeθ]

Ten[djeh]

dies[djeθ]

Ten[djeh ~ dj transformationh]

dieh♪[dje]e]

16

ديج[djeθ ~ d transformationw]

ten ~ deu*[d.]

detz[d transformationw]

deu

- Numbers for '1' and '2' distinguish between male and female forms.

- Asterisks (*) refer to old reconstructable forms.

Number of speakers

The following table includes the Ibero-Romance languages and creoles (in a broad sense: strict Ibero-Romance and Occitano-Romance). Colors indicate subgroup (yellow: Spanish and Spanish-based Creoles, blue: Galician-Portuguese and Portuguese-based Creoles, green: Astur-Leonese, red: Occitano-Romance).

| Pos. | Language | Speakers as mother tongue | Total number of speakers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spanish | 480.000.000 | 577,000.000 |

| 2 | Portuguese | 206,000.000 | 260,000 |

| 3 | Catalan | 3,000.000 | ~10.000.000 |

| Valencia | 1.274,000 | ||

| Balear | 362,500 | ||

| 4 | Gallego | 2.936.527 | ~3.900.000 |

| Eonaviego | 45,000 | ||

| Fala | ~6,000 | ||

| 5 | Occitan | 2.200,000 | ~2.202.765 |

| Aranés | 2.765 | ||

| 6 | Chabacano | 619,000 | 1.300.000 |

| 7 | Crioule | 503,000 | 926.078 |

| 8 | Papiamento | 279,000 | 329.002 |

| 9 | Asturiano | ~100.000 | ~600,000 |

| Leon | ~25,000 | ||

| Mirandés | 8,000 | ||

| 10 | Extreme. | ~25,000 | |

| Cantabrian | ? | ||

| 11 | Sefardi | 98,000 | 150,000 |

| 12 | Forro | 69.899 | 69.899 |

| 13 | Aragonés | 12,000 | 56.235 |

| 14 | Angolar | 5,000 | 5,000 |

| 15 | Palenquero | 3500 | 3500 |

| 16 | Lunguyê | 1,500 | 1,500 |

Contenido relacionado

Italo-Dalmatian languages

Transformational generative grammar

Arabic name day