Hydrodamalis gigas

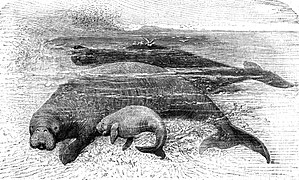

The Steller sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) is an extinct species of mermaid mammal of the family Dugongidae.Its specimens measured about 8 meters long (up to 10 in some cases) and weighed between 4 and 10 tons, they had a forked tail and rough black skin. Compared to its manatee and dugong relatives, it shows its teeth reduced to their minimum numerical expression, being the form best adapted to marine life. The largest sirenian that has ever existed was discovered and described for the first time by the doctor Georg Wilhelm Steller, a member of Vitus Bering's Russian expedition in 1741, lost on the island of Arachka (later Bering Island), off Kamchatka. His report not only excited zoologists, but also seal hunters and whalers who saw a lucrative business, and from that moment it became a coveted prey for sailors, who hunted it in large numbers until its extinction in 1768. The ships followed one after another off Kamchatka, and just 27 years after its discovery the last Steller sea cow was shot down. From the year 1854 there was no trace left.

This enormous mammal was an animal closely related to the dugong (Dugong dugon) that currently lives on the coasts of the Indian Ocean and part of the Pacific from Taiwan to New Guinea. Unlike other sirenians, the Steller sea cow was the only one known to live in cold waters, although it had the same exceptionally tame temperament (to the point of being easily killed). Everything that is known about its biology comes from the writings of Georg Wilhelm Steller. It also fed on a wide variety of algae and marine plants, apparently entire families composed of the male, female and even two small ones lived together. They must have been monogamous and the young could be born at any time of the year, but especially in autumn. The fossil record shows that during the Pleistocene there were times when its distribution extended from the coasts of Japan to those of California, but at the end of the Pleistocene the species only inhabited the seaweed fields of the Bering Sea, and was restricted by last to the Commander Islands, near the Kamchatka Peninsula.

The causes of its extinction were human demand for its high-quality meat, fat and skin. It was described by the German naturalist Georg Steller (1709-1746), who joined the second expedition to Kamchatka (1733-1743) led by Vitus Bering in 1738. The castaways on the expedition only saw this animal among the coastal algae of Bering Island. They had harpooned it and its fat and meat served as food for them. Georg Steller described them as follows:

The meat of the adult individuals is not distinguished from that of ox, and its white and pleasant fat looks like the best Dutch butter, it tastes like sweet almond oil and has a frankly good smell, so that squidillas full of it can be deafened.

The skin was so resistant that it could be used to cover the hull of ships, and the fat and meat, in addition to tasty foods, were proven to be powerful remedies against scurvy due to their richness in vitamin C. The Commander Islands They became an important center for sea cow hunters until the animal's extinction. As far as the Bering Island reservation is concerned, it happened that in the course of the 18th century fur trappers of seals became accustomed to providing themselves with fresh meat there. In October 1754, a group led by a certain Ivan Krassilnikow caused a great destruction of marine colossi. Eight years later a certain Korovin "provided himself with a sufficient quantity of marine beef there". In 1768, one of Steller's former companions, Ivan Popov, visits the island and finds only a single sea cow, and kills it. In later years some sightings were reported on the Commander Islands and other nearby islands, but the existence of this species after 1768 has never been reliably proven.

Presence outside the Kamchatka Peninsula

While there is no direct evidence of the existence of this species in historical times outside the Kamchatka Peninsula, there are accounts of its possible presence outside this region. In the 13th century, the Jesuit Miguel del Barco wrote in his work 'Natural history and chronicle of ancient California' the account given by the missionary Victoriano Arnés (founder of the Mission of Santa María de los Ángeles) about the discovery of a "Woman Fish" ("Mulier Fish"):

"The mulier fish had the figure of a half-body woman up; and of common fish, half-body down. As we found it dry and crushed like a cod, it could not do much anatomy. However, the face, neck, shoulders and white chest appeared, as if it carried a hatch, and had discovered the breasts; although I did not remember if the nipples were distinguished. The rest was covered with scales, and was rowing like other fish. Its grantor would be two palmos, and a proportion of width, similar to cod. No arms or hair were discovered. We find him on the beach in diameter opposite to my mission of Santa Maria, in the South Sea, in a cove that forms at the end of the creek called Catabiñá. "Victoriano Arnés in the work of Miguel del Barco Natural and Chronic History of Old California (S. XIII).

Similarly, in the writings of Miguel del Barco the peculiarity of "female breasts" of the copy:

"While dry, the factions of a human face were distinguished, it can be inferred that, being this fresh and living fish, they represented them with much greater property, and mainly the breasts: when it is known that, or the much old or very prolix disease, it consumes and undoes women's still alive."Miguel del Barco, Natural and Chronic History of Old California (S.XIII)

The description given of the specimen and its illustration (unique in all of Miguel del Barco's work) have suggested that it was a type of sirenian, since similar stories have been given by other explorers when describing manatees and dugongs with "mermaids", being that the presence of "female breasts" It could be explained by a confusion with the typical rounded front fins of the members of this order. Given its location, it has been suggested that it could be a juvenile specimen of Hydrodamalis gigas, being the only sirenian present in the North Pacific in historical times. However, the very small size of the specimen (larger than "two palms" and wide "similar to a cod") and the presence of scales on the body contradict this hypothesis.

As for the location, Miguel del Barco describes that the discovery occurred in an inlet near the mouth of the Cataviña Stream, located in a diameter opposite to the Mission of Santa María de todos los Ángeles. However, there is no cove at the mouth of said stream, so in reality the discovery could have occurred at some point in the Bay of San Luis Gonzaga, where the Arroyo Santa María flows out, so the discovery is would be located in the waters of the Sea of Cortez. Precisely this location, the small size of the organism and the presence of whitish coloration in the ventral part of it, has also led to the hypothesis that this could be a stranded and dried specimen of "Vaquita Marina" (Phocoena sinus).

Contenido relacionado

Bovidae

Tapirus

Capra pyrenaica

Erinaceinae

Lutrinae