Hundred Years War

The Hundred Years' War (French: Guerre de Cent Ans; English: Hundred Years' War) was an armed conflict between the kingdoms of France and England that lasted 116 years, from May 24, 1337 to October 19, 1453. The conflict was feudal in origin, as its purpose was to decide who would control the additional lands that English monarchs had accumulated since 1154 in French territories, after the accession to the English throne of Henry II Plantagenet, Count of Anjou. The war finally ended with the defeat of England and the consequent withdrawal of English troops from French lands (except for the city of Calais).

Origin of name

At the end of the XIV century, contemporaries perceived the exceptional duration of the conflict, but the name by which it was You know, the Hundred Years War, arose much later, in the 19th century. The medievalist Philippe Contamine searched for the first occurrences of the expression: it appeared for the first time in the work Tableau chronologique de l'Histoire du Moyen Âge (Chronological Table of the History of the Middle Ages ) by Chrysanthe Des Michels, published in Paris in 1823. The first textbook to use it was that of M. Boreau, which was published in 1839 under the title L'Histoire de France à l'usage des classes. The first work to use the expression in its title was Théodore Bachelet's La guerre de Cent Ans of 1852.

Fighting sides

Kingdom of France

The kingdom of France at the beginning of the XIV century enjoyed a flourishing agriculture, thanks to the abundant rivers that ran through its territory and its favorable climate for this activity; At that time, it had a population of between sixteen and seventeen million inhabitants, which made it the most populous country in Europe. Both the countryside and the cities showed clear signs of prosperity compared to France in the XI and XII, largely due to the relative peace the kingdom had enjoyed during the XIII and the first part of XIV. The increase in population it had been general throughout Europe, but especially intense in France. The household census of 1328, which included about three-quarters of the population, allows us to know approximately the situation of the kingdom at that time. This had 2,469,987 homes, which was equivalent to some twelve million inhabitants framed in 32,500 parishes. Paris alone had between eighty and two hundred thousand inhabitants, according to the census or 1328, Amiens, between twenty and thirty thousand and Rouen, about seventy thousand by mid-century. The urban population density was greater than in England, the Iberian Peninsula or central Germany. the population determined the felling of a large part of the country's forests to extend the glebas, which were exploited through a very hierarchical feudal system. The increase in agricultural production and the great development of hydraulic energy made it possible to feed the population (famines stopped in the XII century). The growth in the use of iron, the application of new work techniques and the substitution of the ox for the horse as a draft animal allowed cultivating lands that were not very fertile or difficult to access, whose crops allowed feeding a population already dense. Some of this unproductive land was later abandoned in the war and no longer cultivated. The situation of the peasantry had improved, although they were still subjected in many cases to heavy obligations towards the nobility, obligations that were more troublesome than The appearance of the countryside was similar to that of France in the 19th century before the start of mechanization, with small rate changes of crops. The defense of the land remained an essential task of the nobility.

To the strength of the countryside was added that of the only industry in medieval Western Europe: textiles, dominated by the Flemish cities (first Arras, then Douai and later Ypres, Ghent and Bruges, Lille and Tournai), by then part of France, to which other places (Ruan, Amiens, Troyes or Paris) were added. Flemish producers used to sell their rich cloth to Italian merchants at the Champagne fairs, in exchange mainly for luxury products from Muslim countries (spices, silk, leather, jewelry...), although these were in decline at the end of the 13th century Other fairs in various parts of the kingdom also flourished before the start of the war.

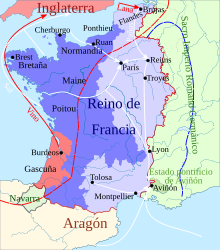

The kingdom was not only impressive for its large population, but also for its size: at the time of the advent of Philip VI of Valois, France stretched from north to south of the Scheldt to the Pyrenees, and from west to east of the Atlantic Ocean to the Rhône, the Saône and the Meuse. It took twenty-two days to cross the country from north to south and sixteen to do it from east to west, according to Gilles Le Bouvier in the XV. In total, the kingdom covered some 424,000 km². It had some sixty regions, very different in language, culture, history and even, in some moments, religion (an example of this had been the southern Cathars). In the north of the kingdom, lengua de oïl was used. the bailiwicks of Senlis and Valois, although the average was 7.9) made it clearly different from the southern part of the kingdom. In the south, on the contrary, the language of Oc or Occitan was spoken, and the culture of the region was influenced by the ancient Roman presence. The area was poorer in agriculture than the north, but richer in livestock, and had a lower population density than the north (about four homes per square kilometer in the counties of Bigorre and Béarn, for example). It was a more autonomous area with respect to royal power, which in the region was exercised by some powerful vassals whose opinions the sovereign had to count on. This did not prevent the monarch from meddling in the internal affairs of his vassals, since his powers had grown since the XII century . It was by then the top of the feudal pyramidal system to which the lower levels owed allegiance.

The clergy played a major role in the social organization of the time. The clergy knew how to read and write and were the ones who administered the institutions; they managed charity works and schools. Religious festivals made one hundred and forty days a year non-working days. Also from the religious point of view there were differences between the north and the south: in this the Carolingian renaissance and the religious orders They had had less weight and some sciences such as medicine stood out more than philosophy and theology, unlike in the north. Two cities embodied this contrast: Paris and Montpellier; The former had one of the most respected universities in the Christian world in terms of theological studies, while the latter had one of the most prestigious medical schools in Western Europe, attended by even students from the Near East and North Africa.

The nobility combined wealth, power and gallantry on the battlefield: they lived off peasant labor, which they had to compensate with their bravery in war and loyalty. The Church had tried to put an end to knights given over to banditry since the late X century: as early as the Council of Charroux in 989, warriors had been asked to give themselves up to the service of the poor and of the Church and were milites Christi («soldiers of Christ») From the 13th century, the king had managed to get it recognized that his power, based on divine right, empowered him to create nobles. protect the people and deliver justice, in exchange for which he enjoyed a privileged material situation. Her social situation had to justify her on the battlefield, where she had to defeat the enemy in heroic combat. The royal army was structured around the cavalry, which was the most powerful in Europe at the time; it was a heavy cavalry that attacked frontally and fought in single combat with the enemy. Added to the desire to stand out on the battlefields was the custom of taking captives, who were later released in exchange for a ransom, which made wars lucrative business for good warriors, while the possibility of receiving a ransom made capturing enemies more interesting than killing them. In reality, and despite the claim of the knights to have a monopoly on weapons, the reality was very different and the style of chivalrous combat was increasingly unsuited to actual warfare.

The Capetian kings had tried to consolidate their power against the great nobility and the papacy by relying on the common people, through the creation of towns, the granting of charters and the meeting of the General Estates of France. The social balance it depended on the acceptance of a strong royal power by the common people that would compensate for the arbitrariness of the feudal lords, and on an increasingly centralized administration that would improve their living conditions. This system was entering a crisis on the eve of the start of the Hundred Years War, as the population growth since the X span> was leading to overpopulation in the countryside and calls for greater autonomy in the cities. Plot sizes dwindled, farm prices fell, and nobility revenues dwindled; The reduction in the income of the nobles made them try to excel in combat to obtain favors with which to increase income.

In three centuries, the Capetian kings managed to consolidate their authority and expand their lands at the expense of the Plantagenets. The royal lands covered almost half the kingdom, the infantados in the hands of the king's relatives were large, and of the former great fiefs at the beginning of the century XIV only four remained, at the ends of the kingdom: the county of Flanders and the duchies of Burgundy, Guyenne and Brittany. The prestige of the French monarchy was immense and in the time of Philip IV the alliances of the kingdom extended to Russia. He also had the support of the papacy at least since the election, precisely in Lyon, a French city, of Pope John XXII, former bishop of Avignon who established his residence there and who clearly favored Felipe VI so much politically as well as economically. He was the second in a long series of French popes. However, despite the confiscations of lands from successive English sovereigns by Philip II, Louis IX and Philip IV, they had retained the duchy of the Guyenne and the peq own County of Ponthieu, which made them vassals of the King of France.

Royal authority spanned the kingdom thanks to a relatively specialized Public Administration. Two aspects were, however, weak in the event that the kingdom waged war: the scarcity of the king's income, which even in times of peace barely covered ordinary expenses and depended essentially on the lands it administered directly, and the lack of a good army. of subsidies) that were obtained haphazardly, with notable reluctance from the taxpayers, and required the granting of extensive concessions and promises by the sovereign. The kingdom lacked a system for procuring the copious means necessary to wage a long war. The king did not have a regular army either: he depended on the arms service owed to him by his vassals, which was limited in space and time and it was not suitable for long-term disputes. From Philip IV, the king had the right to levy, in which all free men between the ages of fifteen and sixty had to participate, both nobles and peasants, regardless of their wealth, in case the kingdom was invaded. This new royal power meant that around 1340 Felipe VI could count on some thirty thousand men-at-arms and as many pawns. These were huge numbers for the time and the cost of assembling such an army was very high, but it had an added drawback: it was a heterogeneous and undisciplined army.

Kingdom of England

The kingdom of England had a much smaller population than France: four million inhabitants; was then suffering from the so-called European «Little Ice Age», which had begun in the XIII century and ended with some products kingdom's agricultural crops, such as wine, which had previously been produced in the south and was from then on only made in Guyenne. Its extent was also smaller than that of the French kingdom, even with Wales, which it had just completely conquered. Edward I of England. It only had one large city: London, with about forty thousand inhabitants around 1340; York and Bristol barely numbered 10,000. The rest of the main towns were merely large towns, generally independent of the nobility having bought the exemption from services.

The peasantry in general enjoyed a position as good as that of France and there was even a group of free peasants under seigneurial tutelage. The country had to specialize its economy and promote trade, which at the beginning of the century XIII remained mainly in the hands of foreign merchants (Flemish, German and northern French). The rainy climate and abundant pastures favored the development of livestock, especially sheep, which in turn increased the production of wool that favored the textile industry (the wool of English sheep is especially fine and of high quality and is easily spun). strength of trade and cities, whose inhabitants needed freedom to set up businesses and limited taxation (much of the state income came from taxes on wool) For their part, the landowners (barons and clergy) were opposed to the increase in taxes, destined to finance the war against Felipe Augusto, especially when this, as was the case during the reign of Juan sin Tierra, resulted in a series of defeats and territorial losses. John had to grant Magna Carta in 1215 which gave Parliament some fiscal control.

Trade made England highly dependent on Guyenne, where a large part and the best English wine was produced, from Flanders, whose clothiers bought English wool, and from Brittany, the source of salt essential for food preservation There was also another large city: Bordeaux, which must have had between twenty and thirty thousand inhabitants. From Guyenne, large canned squadrons with merchandise for Great Britain left on certain fixed dates, sometimes gathering up to two hundred ships. Trade links between Guyenne and Great Britain were close and ancient. Guyenne had almost no wool and grain and had specialized in the production of wine, dyes (indigo) and iron, all of which were imported by Great Britain from the province. mainland, to which it sold cloth and food. Guyenne was the second largest destination for English textile exports, after Germany.

The unity of the kingdom was, however, greater than that of France. Great principalities had not arisen as in the neighboring kingdom and the temporary weakness that the Crown had suffered from Richard I to Henry III had vanished during the subsequent reign of Eduardo I. The rights and possessions of the Crown were clear from the time of this last king, justice was well organized and the local Administration, very different from that of France, counted on the participation of the population, which gave cohesion and strength to the kingdom. The imposition of new taxes depended on the approval of the subjects, whose representation was growing in the embryonic Parliament, which precisely at the beginning of the Hundred Years War acquired its final form of two Chambers: the Upper, which brought together the bishops and great feudal lords, and the Lower, which brought together the knights and the attorneys of the cities and boroughs. As in the case of France, the king of England did not count either. It had the means to fight a long war, it depended on parliamentary approval to impose new taxes and resorted, as Edward I had already done in his campaigns, to various sources of income, from loans - from the "Lombard" bankers, who dominated in return trade in silver—to the contribution or even confiscation of wool.

For two centuries the suzerainty of western France, from the duchy of Aquitaine to the rich and powerful county of Flanders, had spawned conflicts and intrigues between the rival Capetian and Plantagenet dynasties. The dispute had begun in the middle of the XII century and by then the Plantagenet had a wide advantage over their opponents, as they dominated Anjou, Normandy, Maine, Poitou, Aquitaine and Limousin; these territories were confiscated by the King of France during the early part of the 13th century. The vast Plantagenêt empire was reduced to a part of Aquitaine: the Gascon coast with Bordeaux, Guyenne, by virtue of the peace of Paris in 1259. This peace, which was to have put an end to the long disagreements between Plantagenêt and Capet, was the source of subsequent conflicts due to the different interpretation of the situation in the region by the two Crowns: one more king's fief for the French and a quasi-independent territory for the English, which relied on both the loyalty of the population as with close economic ties to it. The long war was a reflection of English interests in France and the continuation of earlier conflicts between the Plantagenets and Capetians that had begun in the mid-century XII. The English kings enjoyed notable support on the continent for their territorial and dynastic claims, among which that of Bordeaux stood out.

The English privileged classes spoke Anglo-Norman, essentially Old Norman with influences from the Angevin dialect, in Plantagenet times and, to a much lesser extent, Anglo-Saxon; this continued until the 1361 decree of Edward III. The common people, for their part, continued to use Anglo-Saxon. The war with France accelerated the governmental adoption of English, which began to be used normally in parliamentary sessions in 1362 and by 1413 was considered the language of the court. French began to be considered the language of the enemy.

Military service was dependent on income and divided men from sixteen to sixty into groups with different weapons depending on their income. Those who did not wish to participate in the expeditions to the mainland could do so by paying a certain amount of money. Royal commissars roamed the kingdom to complete the army with the recruits they considered the best. The main change in the feudal armies of the 1310s-1330s was the reduction in the ratio of knights, especially heavy cavalry, to other combatants. The main cause was the decrease in the number of landowners who could afford the expensive knight's equipment. For this reason, the number of recruits from less affluent social classes was increased, who were armed with less cost; these formed the infantry, which included archers and crossbowmen. Each parish had to provide a certain number of men, trained and equipped, who were only paid one soldier if they had to fight abroad; the king could require any landowner with an income of more than forty pounds sterling to come to serve in the military and, as in France, he had the power to mobilize the entire population. The infantry was essentially fed by men with incomes of less than fifteen pounds, who served as archers or armed with swords. The peons came from the upper layers of the peasantry, since they had to equip themselves and also provide the pony they used to move: it was a mounted infantry, very mobile. The light cavalry was also generally made up of landowners; its members wore leather breastplates, a helmet and iron gauntlets, sword, dagger and spear. The horse archers also used to be landlords, they carried a long bow, two meters long, very effective and deadly in the battles of the Hundred Years War. They used to be placed in tight ranks on the flanks of the army, protected by palisades of stakes, carts or other obstacles; they were capable of firing six arrows per minute, which often decimated enemy cavalry. Between 1320 and 1330 these groups of archers replaced the crossbowmen, who also fought on foot, but could only fire one bolt for every three arrows the archer shot. The other social classes provided the bulk of foot archers, spearmen and swordsmen. The English army was better prepared for defense than for attack.

As for the fleets, they were necessary both for fighting at sea and for transporting soldiers to France. The king had the right to require shipowners to use their ships for military use, without paying for it. the embarked soldiers, who used to be equal in number to the sailors, were generally paid volunteers, the sailors participated in the operations obliged by the royal right to claim their service. The king had his own ships and the obligation to serve others, but most of those who served in the French war were requisitioned merchantmen for operations. Foreign ships were also used, hired for special operations, such as moving large armies to the Continent.

Origins of the conflict

The rivalry between France and England stemmed from the Battle of Hastings (1066), when Duke William of Normandy's victory allowed him to take over England. Now the Normans were kings of a great nation and they would demand that the French king be treated as such, but the point of view of France was not the same: the duchy of Normandy had always been a vassal, and the fact that the Normans had risen to the The throne of England did not have to change the duchy's traditional submission to the crown of Paris.

Cultural, demographic, economic and social causes of the conflict

Medieval European economic progress came to a halt at the beginning of the XIV century. Technical advances and clearing of forests allowed the population to grow since the X century in western Europe, but in some regions production was no longer enough to feed their populations from the end of the XIII century. The division of the plots led to smallholdings: the average area of the estates decreased by two thirds between 1240 and 1310. Some regions such as Flanders were overpopulated, especially due to the low food productivity; in this case, they tried to win arable land to the sea, while a commercial economy developed that allowed food not produced there to be imported. In 1,279 English peasants, 46% had less than five hectares of land, which was considered the minimum area to feed a family of five members. The situation was very similar in France: in Garges, a town near Paris, in 1311 two thirds of the inhabitants had less than thirty-four areas, including the floor plan of the house, which occupied almost twenty. In this situation, any natural catastrophe could ruin families. The rural population became impoverished, the price of agricultural products dwindled and the income of the nobility decreased, while the tax burden grew, which fueled tension among the agricultural population.

Many peasants sought seasonal jobs in the cities, for miserable wages, which in turn led to tensions in urban areas. The Little Ice Age also damaged crops which, given population pressure, caused famines the likes of which had not been seen since the 12th century in northern Europe in 1314, 1315 and 1316: Ypres lost 10% of the population and Bruges 5% in 1316.. The growth of cities exacerbated the lack of food; the supply depended on trade. On the other hand, consumers who had become accustomed to a higher standard of living than before due to the general prosperity, demanded more varied and abundant food; the nobility became accustomed to the consumption of wine and all social classes became accustomed to a more varied and rich companagium (food that accompanied bread). The enrichment of society and the new demands for more expensive made peasants diversify agricultural production. Vineyards grew with the demand for wine, especially in the north and east of France. The English sovereigns, who only had Guyenne left in France, also increased the cultivation of this plant in the duchy, while the Dukes of Burgundy favored the production and export of Beaune wines. But the diversification of production also had a deleterious effect: it reduced the production of agricultural commodities.

The inability of the State to impose taxes in the face of the opposition of the territorial assemblies and to obtain credits made it use the change in the currency law to balance the budget, which meant reducing the state debt in exchange for devaluing the currency The Crown applied devaluations on various occasions during the war with England: 1318-1329, 1337-1343, 1346-1360, 1418-1423 and 1426-1429; the English currency, on the other hand, remained quite stable. The penultimate devaluation was very intense: the Dauphin Charles increased the value of the currency by three thousand five hundred percent. the landowners, fixed by contract. The war was presented as a means for the nobility to compensate for the decrease in their income: the collection of ransoms of captives, pillage and the increase in taxes with the justification of paying for the war supposed additional income. This made the nobility in general and the English in particular, more affected by the decline in income obtained from the peasants, adopt a warmongering attitude. For his part, a conflict also seemed to the French King Felipe VI a good means to improve the situation of the treasury, since it allowed the collection of extraordinary taxes.

French and English cultural and economic influence areas

The modernization of the legal system that had begun in the reign of Louis IX attracted numerous neighboring territories into the French cultural orbit. The influence was due both to linguistic closeness and to the weakness of the emperors who succeeded Frederick II Hohenstaufen in the second half of the XIIIth century and the munificence of the French kings, willing to grant pensions to certain neighboring lords of the empire. In the neighboring Holy Roman Empire, the cities of Dauphiné or the county of Burgundy resorted to the French royal justice to resolve disputes; thus, the king sent the ball of Mâcon to Lyon to settle certain differences and the seneschal of Beaucaire to Vivier and Valence on similar missions. French kings attracted the nobility of these regions by granting them rents and linking them to the kingdom through skillful marriages. The homage that the counts of Savoy paid to the King of France in exchange for the granting of pensions, the heroic death in Crécy of the King of Bohemia Juan de Luxemburg, father-in-law of Juan the Good, and the sale of Dauphiné to the grandson of Felipe VI by Count Umberto II, ruined for being unable to collect taxes and without heirs after the death of his only son are paradigms of this phenomenon. On the contrary, English kings had a problem being vassals of sovereigns French by virtue of their possession of Guyenne, since any disagreement with them was settled in Paris and, therefore, generally against them.

Economic growth caused certain regions to become dependent on some of the two kingdoms. At that time the main way of transporting goods was the fluvial or maritime. The County of Champagne and Burgundy supplied Paris by the Seine and its tributaries and were therefore pro-French. Normandy was divided, as it was the edge of the Parisian economic region and the one bordering the English Channel, an increasingly important commercial area thanks to the naval technical improvements that allowed Italian ships to circumnavigate the Iberian Peninsula with increasing ease.. The Duchy of Aquitaine, which exported wine to England, Brittany, which exported salt, and Flanders, which imported English wool, were consequently in the zone of English influence.

The Flemings, who wanted to get rid of the French tax burden, rebelled several times against the King of France, which led to a series of battles: Courtrai (1302), Mons-en-Pévèle (1304) and Cassel (1328). They collaborated with the King of England and in 1340 recognized Edward III as the legitimate King of France.

Both France and England sought to expand their territories to increase tax revenue and improve the state of their treasuries. The intrigues of the corresponding monarchs to gain control of Guyenne, Brittany and Flanders sparked the long war between the two kingdoms, which lasted one hundred and sixteen years.

The dynastic question

The dynastic problem that arose in 1328 actually originated a decade earlier: Louis X of France died in 1316, just eighteen months after his father Philip the Fair; his death marked the end of the long so-called age of "Capean miracle", which had lasted from 987 to 1316 and during which successive kings had always had a male child to whom they would inherit the kingdom. State management during his father's lifetime had given great stability to French politics for three centuries. Tradition had established the succession of the Capetians to the throne, from male to male, although there was no defined system of succession. The kings they had not legally defined the system of transmission of the crown nor were there precedents for kings who only left daughters to succeed them. On the contrary, Louis X had only one daughter with his first wife, Margaret a from Burgundy, convicted of infidelity: Juana de Navarra.The king was deceased, his second wife had had a son (November 13, 1316): Juan the Posthumous, who barely survived childbirth four days.

For the first time, the heir to the French crown was a woman, Juana de Navarra. The decision that was made then served as a precedent for the later one in 1328: the infidelity of Queen Margarita served as a mere pretext to deprive Juana of the right of succession and hand over the throne to the brother of the deceased Luis, Felipe V, who had been regent during the pregnancy of his sister-in-law and carried out a coup that, despite the protest of some nobles, was approved by an assembly of barons, bourgeois and professors from the University of Paris. The usurpation and the break with tradition The feudal power that would have made Joan queen displeased powerful lords of the kingdom, who were absent from Philip's coronation at Reims (January 9, 1317), but not enough to encourage them to take up arms against him; Little by little, Felipe managed to silence his adversaries.In reality, the choice of Felipe and the abandonment of her niece were due to the fear that she would end up marrying a foreigner who could end up seizing power in the kingdom. The Capetians had increased their possessions by making those of their dead vassals without male heirs pass to the Crown. Felipe IV had precisely included a "masculinity clause" shortly before he died, which meant that the infantry of Poitou could return to the Crown in the event that his lord did not have a male heir. It was not the Salic law that was applied to choose the new king; this appeared as a justification thirty years later, around 1350, in the work of a Benedictine friar from the Saint-Denis abbey who wrote the official chronicle of the kingdom and who mentioned it as a justification for the advent of Philip V, in the midst of the propaganda struggle which he was then waging with Edward III of England. The law dated from Frankish times and excluded women from the "salt land", an adjective that comes from the river Sala, the modern IJssel in the Netherlands, a place settlement of the Salian Franks. It was recovered and used as a weighty argument in favor of the king's legitimacy in the disputes of the time, although the female inheritance of fiefs had been applied without problems for some time. of the Crown that made it elective in the style of the imperial or papal actually broke with the feudal tradition that allowed female inheritance and caused great scandal.

Philip V reigned for a short time and also died without a male heir, so his younger brother, the youngest of the family, Carlos IV, inherited the throne, taking advantage of the precedent set by Philip in 1316; he was crowned in 1322. He had been one of the staunchest defenders of his niece Juana, but this time he removed not only Juana from the throne, but also the daughters of her recently deceased brother Felipe. His transfer of power aroused no complaints. His reign was also brief, six years, and before he died, since his third wife was pregnant, he commissioned the nobility to make his son king if he turned out to be a boy and to choose the new sovereign for herself if she was a woman. The newborn turned out to be a woman, so she was removed from the succession.

Carlos, the third son of Felipe el Hermoso who had attached the French crown, also died without leaving a male heir on February 1, 1328, leaving the succession situation as follows: Isabella of France, last daughter of Felipe el Hermoso, had a son, Edward III, King of England and French feudal lord as Duke of Guyenne and Count of Ponthieu, who ran for the title, despite the fact that the precedents of recent years made it unclear whether the rights that the mother could not exercise could pass to the son; another applicant was a first cousin of the last three kings, Felipe de Évreux, king of Navarre and husband in addition to Juana, the daughter of Louis X who was rejected in 1316; the nobility, however, preferred Philip VI of Valois, another cousin of the last three kings. He was the son of Charles of Valois, younger brother of Philip the Fair and therefore heir through the male line of the Capetians, although in a less direct way than Eduardo. The three pretenders had firm rights to the throne, but the first two had the disadvantage of being much younger than the third, who was also a native of the kingdom and already held the regency. The peers of France refused to hand over the crown to a foreign king, following the same criteria that they had already used ten years before, or perhaps they feared that if they chose Edward, the government would remain in the hands of his intriguing mother, hated in France. and that at that time that of England dominated; Edward was, in addition, a Plantagenet, and therefore suspected of being a rebellious vassal and prone to conflict with the Crown. Philip, who had first been made regent by the nobles, was recognized as king after birth. of Charles's posthumous daughter on 1 April. The election aroused no complaints in France: the new king had some experience, enjoyed the support of the nobility, and was known to the court. The coronation took place on 29 May. Philip compensated Joan of Évreux with the kingdom of Navarre, whose crown had been held by the three French kings who had preceded him, although he kept for himself Champagne, which had the same origin and in exchange ceded the counties of Angoulême and Mortain —of lower value— and certain rents; In fact, given that both in Navarre and in Champagne, the inheritance of a woman was something firmly established, the two territories should have passed to Juana. This was then a minor, but when she reached the majority in 1336, she endorsed the agreement made on his behalf years ago.

Edward III paid homage to Philip, although with notable reluctance and delay, after various pressures, for his duchy of Guyenne and for Ponthieu, after he was threatened with a new confiscation of the duchy. King of England had recognized himself as a vassal of Felipe VI in June 1329 and had even made concessions in Guyenne, while reserving the right to claim the territories arbitrarily confiscated by the French monarchs. Philip did not meddle in the Anglo-Scottish conflict, but that was not the case. Felipe confirmed French aid to David Bruce. Faced with this attitude, Edward III once again proclaimed his rights to the French crown, which served as a pretext to unleash the war against Felipe. In reality, the dynastic dispute was a secondary reason for the contention until the times of Henry V of England, a mere argument by Edward III to reinforce his position, since the real objective was not the crown of France, but sovereignty over certain French territories.

The dispute over Guyenne: the problem of sovereignty

The dispute over Guyenne had a more relevant role than the dynastic issue as a trigger for the war. The region was a notable problem for the kings of England and France: the former was a vassal of the latter by virtue of possession of this territory, in principle of French sovereignty. This allowed, in theory, to appeal against a decision given in the region before the court in Paris and not in London, something that the vassals of the duchy did when they received rulings with which they they were not satisfied and that the agents of the king of France encouraged. This allowed the French king to annul the legal decisions that his English counterpart made in Aquitaine, something totally unacceptable for the English, who sought to administer the territory without French interference. The sovereignty of the territory remained in dispute between the two Crowns for several generations and was the main reason for the war.

The first French confiscation of the territory from the English king occurred as early as 1294, when Philip IV seized it temporarily from Edward I, to whom it was returned in 1297. Philip VI's father had occupied an English bastide in 1323 in Saint-Sardos during an expedition undertaken by order of the then King Charles IV; the place was in the middle of the duchy of Guyenne, which had aroused unsuccessful but vehement complaints and resources from Edward II of England and the feudal lord of the area, Raymond-Bernard de Montpezat. The latter decided to take up arms on October 16 of that year, while the French sovereign's attorney was in Saint-Sardos to sign an alliance. He appeared at the head of his hosts and reinforced by English soldiers before the castle, which he attacked, and razed the annexed town. He put the garrison to arms and hanged the representative of Charles IV.The attack served as a pretext for the Parisian Parliament to confiscate the duchy of Guyenne in July 1324, arguing that his lord had not paid due homage to the king. The French monarch then easily invaded almost all of Aquitaine, as had happened the previous time, although he reluctantly returned it in May 1325, at the request of Pope John XXII and his own sister, Queen of England. Edward II he had had to compromise to get the dukedom back to him: he had had to send his son, the future Edward III, to pay homage and despite this Charles intended to amputate the Agenais and the Bazadais from the restored Guyenne. The evacuation of the duchy had been delayed first by English dynastic problems and then by the non-payment of the amounts agreed upon both for the change of lord of the duchy and the war indemnity. The two temporary confiscations had served to subdue obedience to a vassal considered by the French court too autonomous, but the ease of the conquest gave the mistaken impression that the gesture could be repeated when necessary.

The situation seemed to ease in 1327 with the accession to the English throne of Edward III, who recovered the dukedom in exchange for promising to pay war compensation. The French nevertheless resisted returning the seized lands, in order to force to the new English king to pay homage, which he agreed to do on June 6, 1329. Felipe VI stated during the ceremony that the act of vassalage did not include the lands separated from the duchy by Charles IV (especially the Agenais). Eduardo, for his part, considered that the tribute lawsuit did not deprive him of claiming the lost lands, as he did in the following years. By then, Guyenne had been reduced to a coastal strip where the French royal agents they did not stop acting.

Edward found himself in a weak position during the early years of his reign, until a conspiracy of disgruntled barons enabled him in November 1330 to execute Mortimer, banish his mother to a remote castle, and seize power. This forced him to maintain a conciliatory attitude with Felipe VI, to whom on March 9, 1331 he confirmed that the homage he had paid for his French possessions was legitimate. The two kings met secretly a few weeks later to resolve the pending problems (drawing of the borders of Guyenne, treatment of the exiled nobles for remaining faithful to Eduardo during the confiscation of the duchy, fixing of possible war indemnities...), which were not resolved despite the long negotiations that followed.

The peripheral fronts

Scotland

England had to face the Second Scottish War of Independence, fought between 1332 and 1357. Wars between the two neighboring kingdoms had been continuous since the end of the century XIII. The neighboring kingdom had been subjected to vassalage in 1296, taking advantage of the death without male heirs of Alexander III, through marriage. Scotland was linked to France by the "old alliance » from October 23, 1295 and Robert the Bruce crushed the English cavalry at the Battle of Bannockburn (1314), far superior in number to the hosts of the Scotsman, at the head of an army of dismounted men-at-arms protected from the charges pikemen. The English copied this combat system: they decreased the size of the cavalry and increased the number of archers and men-at-arms who fought on foot, who protected themselves from cavalry charges with spiked stakes. soil; soldiers rode on horseback for faster travel, but fought primarily on foot. The Scottish Wars also allowed the English army to gain experience and strength.

Edward III used this new way of fighting in the Scottish wars in which he supported Edward Balliol against David II, son of Robert the Bruce. He died in 1329 when his son David was still a child of seven, making it who encouraged Edward III to intervene in Scotland with his own candidate, Balliol, first indirectly, with money and soldiers, and then, in 1333, openly. The new tactic allowed the English to win several major battles, including including that of Dupplin Moor in 1332 and that of Halidon Hill in 1333. David II was defeated, fled Scotland and took refuge in France, where Philip VI gave him protection. Edward Balliol was crowned King of Scotland, as a vassal of England, to which he ceded the lands south of the Firth of Forth, with little popular support. Pope Benedict XII tried to reconcile the English and French kings, but could not prevent Philip from helping David II financially and militarily to recover the Scottish throne, to whom he dispatched in the spring of 1336 some of the troops he had gathered to undertake a crusade that ultimately did not take place. French preparations to support David II's embattled supporters worried England, which even feared a French invasion of Britain. Fighting resumed again in the Anglo-Scottish border in 1342, fanned by the French monarch.

The Scottish campaign allowed Edward III to form a modern army accustomed to new military tactics, also those used by cavalry: the looting cavalcade in which a contingent traveled great distances dedicated to devastating enemy territory it had also been used in Scotland.

Artois

In the county of Artois one of the usual succession crises of that time arose: Count Robert II died in 1302 without leaving any male heirs. His daughter Matilde, wife of Otto IV of Burgundy and mother-in-law, inherited the fief of Felipe V and Carlos IV of France. However, the grandson of the deceased Roberto, felt neglected and poorly compensated and claimed several times, although in vain, that the county be given to him. Matilde died unexpectedly in November 1329 when the Parliament of Paris was reviewing a new claim by Roberto and some accused Roberto of having poisoned her. Within weeks Matilde's daughter and heiress also died and the county passed to the queen's brother, the Duke of Burgundy. The documentation Robert presented to support his claims was false and Parliament finally ruled against him in 1331. Investigations began on Robert, who fled to his lands and then disappeared, refusing to appear before his investigators. gadores. He was finally dispossessed of his property in April 1332, the year in which he fled to take refuge with the Duke of Brabant, who took him in for three years until the other nobles of the region forced him to expel him. He fled and took refuge in England, whose king he also recognized as sovereign of France. This submission made the English court hope that other great French lords would follow his example and recognize Edward III as king.

Flanders

Flanders was at the beginning of the XIV century in great tension, in an unstable balance between the power of the count and autonomy of the great industrial cities such as Bruges, Ghent or Ypres and between the political dependency of France, to which the county belonged, and the economic dependency of England, whose wool supplied the textile industry. A socio-political revolt had broken out in Bruges in June 1323, which spread along the entire coast of the county, attracting above all the well-to-do peasantry, who banded together in units with their own captains, drove out the earl's tax collectors and destroyed some houses of the nobility. Burgomaster of Bruges requested the help of Edward III.

The count did not have his own army since he could not put down the uprising by himself. He went to pay homage to Felipe VI for the county in 1328 and took advantage of the trip to request immediate help from the new king against the rebels. Social conflicts made the French Crown intervene militarily, which in August 1328 crushed the rebellious peasants and artisans at the Battle of Cassel, in which eleven thousand of them perished at the hands of the French cavalry. The intervention The military strengthened ties between Felipe VI of France and Count Luis de Nevers, who had recovered the county thanks to the king's intervention and preserved it through terror, and undermined English influence.

First disagreements

In the mid-12th century 12th century, the Norman dukes were succeeded by the Anjou dynasty, powerful counts who held territories in the west from France. The Angevin duke Henry Plantagenet, married to Eleanor of Aquitaine, acceded to the English throne as Henry II of England, thus bringing his possessions and those of his wife, the duchy of Aquitaine, to the British kingdom.

Philip II of France, in his struggle to limit the power of the English sovereigns, supported the rebellion of some of the sons of Henry II and their mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, although the rebellion ended up unsuccessful. Richard the Lionheart, one of the sons who participated in the failed rebellion, succeeded his father to the throne in 1189.

Treaty of Paris

Henry III of England (1207-1272) inherited the throne at just nine years old, bringing with him a period of anxiety and fear that led to the unfavorable Treaty of Paris in 1259. Henry formally abdicated to French King Louis IX all the possessions of his Norman ancestors and all the rights that may correspond to him. This included the loss of Normandy, Anjou, and all his other possessions except Gascony and Aquitaine, which he had inherited through his mother's line. These two regions were subject to homage, a kind of payment, rent or tribute that Enrique would grant to the French king to preserve them.

Edward I

Edward I of England, son of Henry III, was not satisfied with this situation of submission: he built a base of military and economic power far superior to that of his father and wanted to place his crown once again in a position of strength In the continent. He began hostilities against the France of Philip III (which lasted four years: 1294 to 1298) but, more dedicated to consolidating his power within England itself, he did nothing more with respect to France.

When he passed away, another period of convulsions struck England. A strong, motivated and organized Scotland, led by Robert the Bruce, defeated the English on several occasions, defeating Edward's successor, Edward II, and achieving the long-awaited independence.

The War of San Sardos and Edward III

Between 1324 and 1325 a new war broke out between England and France, known by historians as the War of San Sardos because of the town where the main actions took place. The English crown soon passed into the hands of Edward III, who was only a child, but despite everything he was not willing to let himself be defeated so easily. The King of France, Charles IV, died, like his predecessors, without leaving a male heir.

The Capetian Curse

The death of Charles IV marked the end of the powerful and long Capetian dynasty. It had been founded by Hugh Capet in 987, and had produced a long series of powerful monarchs including Louis VI, Louis VII and Louis VIII, all of whom were commanders in the Crusades. After the death of the next king, Saint Louis, guide and captain of the crusade against the Cathars, the Capetian dynasty had yet another powerful king: Philip the Fair. With him began the decline: Felipe destroyed the ancient and noble Order of the Temple, taking many of its leaders to trial and burning, especially its last Grand Master Jacques de Molay. Tradition has it that De Molay, standing on the flames that would consume him, cursed Philip the Fair, the Pope and the Capetian family, prophesying his soon extinction and oblivion.

In fact, Felipe IV died in 1314, during the same year as the execution of the Templars. He had three children. The eldest, Louis X the Obstinate, was crowned in August 1315 and died a few months later, while his wife was pregnant. The newborn child was to be crowned with the name of Juan I; Due to his young age, the middle brother of his father, Felipe, was named regent. The little boy died as a baby, which is why he is known as John the Posthumous. Thus, his uncle Felipe must have been crowned immediately under the name of Felipe V el Largo. This king, though energetic and intelligent, was in poor health and died only five years later, leaving behind four daughters who could not inherit under the Salic Law that he himself invoked in order to succeed his nephew. He was then succeeded by the third son of Felipe el Hermoso (and therefore little brother of Luis X and Felipe V): Carlos Capeto, who reigned under the name of Carlos IV.

The supposed curse of the Templars ended on February 1, 1328 when this king died, leaving only two daughters (one posthumous) and no male to inherit. In just fourteen years, and after four brief reigns, the Capetian dynasty had been extinguished.

Intrigues and declaration of war (1330-1337)

The tension between the two sovereigns increased, fueled by the bellicose attitude of the nobility of both kingdoms, and ended up unleashing war in 1337.

The king of France collaborated with the Scots in their fight against England, an attitude with a long tradition of the Capetian kings, embodied in the so-called "old alliance" (Auld Alliance). Edward III had expelled David Bruce of Scotland in 1333; Felipe VI had welcomed him in the Gaillard castle and rearmed his supporters, preparing the return of the Scotsman to his kingdom. In 1334 Felipe summoned the English ambassadors, among whom was the Archbishop of Canterbury, to inform them that Scotland should also to be included in the general peace that France and England were negotiating and seemed about to be signed. In 1335, David the Bruce attacked the Channel Islands with a fleet paid for by the French king. The offensive failed, but it made Edward III fear that it was a mere prelude to the invasion of his kingdom.

The French intervention in Scotland, small as it was, convinced Edward that war with France was inevitable. Parliament met in Nottingham in September 1336 to condemn the French monarch's actions and approve subsidies to defray expenses of the coming new war. The Government then left York, where it had spent the previous four years because of the Scottish Wars, and returned to London, where preparations for war began. Troops were dispatched to Guyenne and a station was posted. squadron in the English Channel, while Felipe did the same in Normandy and Flanders.

The resumption of the Aquitanian conflict, which negotiations failed to resolve, and the support of the Valois for Edward III's Scottish adversaries made him once again assert his succession rights to the French throne. Philip VI had confiscated him Guyenne on May 24, 1337, accusing him of felony. This third confiscation was intolerable to Edward III, who reacted in turn by claiming the French crown for himself: he dispatched the Bishop of Lincoln to Paris on May 7. October of that year to throw down the gauntlet as a challenge to Felipe, a gesture with which the contest began, although there had already been clashes in the previous months. The two sides had been preparing for war for a long time, seeking allies and preparing armies. The third confiscation of Guyenne was the trigger for open warfare.

Main phases of the conflict

The Hundred Years' War had a symmetrical structure in which a sequence of stages was repeated: between 1337 and 1380 the three stages occurred for the first time and were repeated later. These were a collapse of the power of the French monarchy, followed by a period of crisis and then another of recovery. These same stages were repeated between 1415 and 1453. Between both time periods there was a long truce due to the internal conflicts suffered by both sides.

Each of the two great periods of combat can be further subdivided into two:

- From 1337 to 1364, the tactical genius of Edward III of England allowed him to obtain a series of victories on the enemy cavalry. The French nobility was completely discredited by the successive defeats and the country plunged into the civil war. The English took over much of the French kingdom under the Brétigny Treaty.

- From 1364 to 1380, Carlos V carried out a slow recovery of territories, hoping to overcome the national feeling of the population. It allowed the English to devastate the fields in their cages and avoided the dismantling of the Great companies against the population by sending them to fight Castile. He avoided the camp battles, which had been disastrous for the French at the previous stage of the conflict and devoted himself to regaining strong positions through sieges. Thus, Eduardo III was left on the continent more than Calais, Cherbourg, Brest, Bordeaux, Bayonne and some castles of the Central Massif in 1375.

- From 1380 to 1429, the minority and then the madness of Charles VI of France allowed the great lords of the kingdom to do with power, which unleashed the rivalry between the successive Dukes of Burgundy and that of Orleans, finally transformed the civil war. Henry V of England took advantage of it to regain territories. The French were beaten overwhelmingly in the battle of Azincourt. The murder in 1419 of Juan I of Burgundy made the Borgoñones collid with the English and the armañac party collapsed. Henry V espoused the daughter of Charles VI by virtue of the Treaty of Troyes of 1420, he became the heir of this and he coined in himself the titles of king of England and regent of France. Dolphin Carlos was undone. Henry VI of England succeeded his father, who died unnoticedly, when he was still a few months old, but he was granted the titles of King of England and France.

- From 1429 to 1453, the English were expelled from France gradually. Juana de Arco represented the national feeling and made Charles VII crown despite the agreement in Troyes. The English, without great support among the population, were gradually losing territories. The 1435 Arras Treaty put an end to the Anglo-British League and inclined the fate of the conflict definitively for France. The English only retained Calais in 1453, after the defeat they suffered in Castillon, although peace still took place: it was signed in 1475, already in the times of Louis XI of France and Edward IV of England.

The war

Among the children of Philip IV the Fair was Elizabeth (called the "Wolf of France"), who was the mother of Edward III of England. The young king, only sixteen years old, tried to claim his right to the throne of France, he considered that the French crown should pass to his mother. Even so, if the English thesis were accepted, the daughters of Louis X, Felipe V and Carlos IV would have a greater right to transmit the crown, over their aunt Elizabeth of France.

France did not agree, therefore they invoked the Salic law, which prevented the transmission of the crown through the female line, and therefore decided that the crown recently abandoned by the Capetians would pass to the younger brother of Philip the Beautiful (and uncle of Luis X, Felipe V and Carlos IV): Carlos de Valois. But it was 1328, and Carlos had died three years before. In this way, it corresponded according to the French theory to crown his son, Felipe de Valois, under the real name of Felipe VI. This was the first monarch of the Valois dynasty, who reigned in France without Edward III being able to do anything to prevent it. Now, it was up to Edward to pay (and pay) homage to the proud Philip for his meager possessions, the few he still had in France.

The victories of Edward III (1337-1364)

Indirect warfare

At the beginning of the conflict, Edward's objective was to claim the crown of France for himself as the grandson of Felipe el Hermoso, while for Felipe VI the goal was the recovery of Guyenne and the defeat of the royal claims of his English enemy.

The fighting did not begin immediately after the declaration of war in 1337 due to the financial hardship of the two kings, which forced them to request the approval of the taxes necessary to cover the conflict to the respective parliaments and local assemblies, often in exchange for the confirmation of privileges, the granting of new ones or exemptions. It was then that Estates arose in France, still loosely organized assemblies in which taxpayers haggled over their financial support to royal representatives. of money made the suspension of hostilities proposed by the pope for the first six months of 1338 accepted. de Blois, a relative of Felipe VI in the War of the British Succession. For his part, Felipe supported the Scots in the war they were waging c against the English.

Naval Operations

The first years of the war were favorable to France at sea. French ships and those of their Italian mercenaries sailed the English Channel, seized the Channel Islands and even sacked some enemy ports both in Great Britain as in France. The Normans even prepared an invasion of England in 1339, which finally did not take place, although the preparations made allowed a large fleet to be sent to Flanders in 1340, which was to prevent Edward from crossing to the continent.

Eduardo's German alliances and fighting in Flanders (1336-1345)

The English sovereign was intriguing while in Flanders: his marriage to Philippe of Hainaut allowed him to establish links with northern France and the Holy Roman Empire. In addition, Robert of Artois had been a refugee in London since 1336. Edward He had bought the alliance of the Count of Hainaut - Count of Holland and Zeeland also, and Edward's father-in-law - and that of Emperor Louis IV of Bavaria (August 26, 1337) for three hundred thousand guilders and both the Duke of Brabant and the Count of Gelderland were favorable to him.

Edward III reacted by prohibiting the export of wool in August 1336 and the import of cloth in February 1337, which left a large part of the workers in the cloth industry unemployed, many of whom emigrated. Luis de Nevers arrested the English merchants in Flanders, and Eduardo the Flemings who were then in England. The economic crisis that unleashed the wool embargo caused the bourgeoisie to seek English collaboration in exchange for recognizing the authority of Edward III. The economic threat caused the region to revolt against the French in 1337. At the same time, the English king supported the new textile industry in Brabant, a territory with which it was allied, and invited weavers unemployed Flemings to England to help develop an English industry. Thus, if Flanders remained neutral or sided with Philip VI, England could ruin its economy by cutting off its wool supply. He intensely affected the Flemish drapers, who rebelled against their count Louis I of Flanders, led by Jacob van Artevelde, a wealthy bourgeois from Ghent, who, after seizing power in the region, sided with the English king. Philip tried unsuccessfully to contain the rebellion in Flanders, even allowing the county to remain neutral in the war with England. The rebel leader was extending his control over the county from Ghent during the first months of 1338; the commission of representatives of cities that he chaired had authority from Bailleul in the south to Termonde in the north. Count Luis, for his part, considered having van Artevelde assassinated and attempted to take several of the main cities by surprise with the collaboration of of the nobility of the region, without success; Frustrated, he took refuge at the French court in February 1339. The rebels agreed with England to resume the wool trade and signed a commercial agreement in June 1338; in July there was a first limited shipment of wool. However, the rebels, more antagonistic to their earl's mismanagement than staunch supporters of the English king, for two years avoided becoming too closely attached to Edward. Edward visited Antwerp and his The Duke of Brabant allied in July 1338 to try to get the Flemish cities to go from the neutrality agreed in the months before to the alliance with England, but he did not succeed. For the moment, the Flemish rebels limited themselves to adopting a neutrality favorable to the English monarch. The trip served, however, to strengthen ties with the emperor: Edward visited Emperor Louis of Bavaria in Koblenz on September 5 and he appointed him imperial vicar and recognized his rights to the French crown, to money exchange. The charge transferred to the English sovereign the imperial powers in the north of former Lotharingia. The emperor made the German lords of the region promise to help Edu ardo in his war with Felipe, to which he himself committed himself for seven years. Edward had all the lords of the Netherlands come to pay homage to him - only the Bishop of Liège was absent from the successive ceremonies -, which served to to increase his apparent power, but also to prevent military operations before the winter of 1338-1339 arrived. Edward's financial difficulties in sustaining the onerous German and Dutch alliances were increasing.

The two belligerents had trouble raising troops, so the campaign of 1339 began late in the fall. The English king had spent from July to late September waiting in vain for the arrival of his would-be troops. German allies. He tried in vain to seize Cambrai, which was defended by a French garrison. He pushed into Picardy and tried to fight a pitched battle with the enemy, but the enemy prevented him and the English ruler eventually withdrew north in late October. The fifteen months of stay in the Netherlands, the alliance of numerous princes of the region and the obtaining of the imperial vicarage had resulted in a campaign of meager results.

Edward came to deal with the Flemish after being deserted by the German princes in the campaign of 1339. Until then, he had refused to make any substantial financial concessions to the Flemish insurgents so as not to harm his Brabant allies. The league between Count Louis I of Flanders and the French king outraged and frightened the Flemings, who were also displeased with the increase in fiscal pressure and fearful that the nearby French army would again serve to crush their uprising against the count, as had happened in 1328. The French threat made Van Artevelde more willing to agree with Eduardo, whose troops he needed to protect himself. The resumption of the conflict with France would have meant, however, the payment of a heavy compensation to the pope, who could excommunicate the count or even launch the interdict against the Flemish cities. To circumvent the refusal of the Flemish cities to rescind their oath of allegiance to the King of France, Edward hesitantly agreed to present himself as such, so that the rebels could bind themselves more closely to him without apparently breaking their allegiance to the French King, who from then on it would be him. The final alliance was reached on December 3, 1339, at great cost for the English: transfer of the wool export center from Antwerp to Bruges, return of the southern castles delivered to the French king in times of Felipe IV, granting a subsidy of one hundred and forty thousand pounds to improve the defense and naval and land aid in the event of a French attack. The Flemings promised to help Edward militarily, whom they recognized as King of France. Edward III appeared in Ghent in January 1340, where he swore to respect the privileges of the cities and signed three fundamentally commercial treaties with the Flemings. The English monarch raffled off the t Flemish fear of excommunication by promising to send English priests, who would say Mass despite the papal prohibition. He then returned to England to raise funds to pay his Dutch creditors, to whom he left his wife and his children as pledges. minor children. It was then that their third son (called "John of Gaunt"), John, later Duke of Lancaster, was born in Ghent.

The Flemings resumed traffic with England, so the French sent the fleet to La Esclusa, at the mouth of the channel that connects Bruges with the North Sea and the only good port in the Flemish county, in order to impose a naval blockade of the region. Edward arrived in the area with the English fleet in June 1340, after four months of preparations; it was somewhat larger than the enemy and was much better commanded. The disaster of the fleet at the Battle of the Lock on June 24, 1340, which had been reinforced by Breton navies, put an end to French naval dominance and began the war. English, which lasted several years. The severe defeat derailed plans to send French troops to Scotland and allowed Edward III to resume the wool trade with Flanders. Edward then headed directly for Tournai, the first point of royal rule. French in the area, on the banks of the Scheldt, at the head of some thirty thousand soldiers, their own and their Flemish allies.

He failed to seize Tournai, which he besieged for two months with Artevelde and the Duke of Brabant, so he ended up agreeing to a truce (September 1340) which lasted until June 1342. The lack of a victory clear on either side, the arrival of winter and the financial difficulties that afflicted both prompted them to sign the truce, proposed by the pope's emissaries. Eduardo secretly fled the area, where he was harassed by creditors, and he returned to England. His debts ruined several Italian banks that had helped pay for his two failed campaigns of 1339 and 1340. Shortage of English subsidies subsequently unraveled Edward's costly alliances in the Holy Roman Empire. Edward lost support of the Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria and the German lords, little interested in a contest that had not brought them income as they had hoped. The Emperor stripped Edward of his position as imperial vicar and reconciled with Philip VI during the spring of 1341. The archbishops of Mainz and Trier followed his example and the dukes of Brabant and Gelderland renewed the truces they had agreed with the French sovereign. The sharpening of the confrontation between the emperor and the new Pope Clement VI (elected in 1342), from then on made him disengage from the Anglo-French conflict to concentrate on the one that opposed him to the pope.

The resumption of the wool trade was not enough, however, to end the crisis in Flanders, which gradually undermined the authority of Jacob van Artevelde. The county plunged into a series of continuous internal disputes between supporters and opponents of Van Artevelde, between cities and even between trades. In addition, Pope Clement VI had excommunicated the Flemings, accused of perjuring their lord, which it facilitated Louis II's return to the earldom in 1342 and forced Jacob van Artevelde to radicalize his position. He refused to recognize Louis's authority and offered the earldom to Edward of Woodstock, son of the King of England, later nicknamed the " Black Prince". The project did not come to fruition: Van Artevelde was assassinated during a revolt on July 17 or 24, 1345, shortly after Eduardo had appeared with a fleet, which sailed after learning of the murder of his ally. Flanders left the league with England to resume the one they had with France.

Succession of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany was a French territory that retained distinct features, including the Celtic language brought by immigrants from Great Britain. Duke John III died on April 30, 1341 without a direct heir. The inheritance was disputed by a niece of the deceased, Juana de Penthièvre, and Juan's brother, Juan de Montfort, who denied the possibility of the dukedom remaining in the hands of a woman, despite Breton custom allowing it. Fundamentally, Celtic Brittany favored John while French Britain (the south and east of the duchy) preferred Juana and her husband. Felipe VI had to settle the matter by accepting the homage of the new lord of the fief, but Juan feared that he would do so favor of her rival, who was at the time the wife of Charles of Blois, the French sovereign's nephew. Consequently, she tried to seize the duchy by force: she occupied the main strongholds by surprise between May and July 1341, but did not obtain the support of the high clergy nor of a large part of the nobility, who called King Philip to his aid. John had marched with a retinue to England, where he met Edward III in July, who promised to help him. On his return he went to Paris, where the court of peers judged the Breton inheritance, but, seeing that the king was hostile to him, he fled the city in disguise and returned to Brittany. The court ruled against John on 7 September. Philip, after receiving the homage of the new Duke Charles, he dispatched the dauphin at the head of an army that appeared before Nantes and arrested Juan in November, after a siege of the square. The dispute seemed settled, but in reality it lasted almost twenty-five years, partly due to the almost continuous absence of the pretenders to the ducal crown, who left the fighting in the hands of their supporters, who delayed the war, which was both their way of life and their pastime.

Juan had the support of the cities, part of the small nobility and a section of the peasantry, in addition to the vigor of his wife Juana de Flandes, who became the head of his party. Juana recognized Edward as king of France to obtain his support. The succession dispute turned into a civil conflict, which the English joined in 1342, when they came to the aid of Joan of Flanders, surrounded by Charles of Blois in Hennebont, where she had fled. defended with great verve. Two more English contingents landed during the summer of 1342; Robert of Artois arrived in one of them, who was mortally wounded in combat. Edward arrived in October, after having fought with the Scots, and surrounded Vannes, where Charles had taken refuge after abandoning the siege of Hennebont. The Duke of Normandy came to his aid in mid-December and then Felipe VI himself joined the campaign. Bad weather made the two sides accept the mediation of two cardinals, papal legates, who managed to sign a new truce of two years on January 19, 1343, the Truce of Malestroit. John de Monfort was released in exchange for not returning to Brittany, although he did, and his wife and son evacuated the duchy with the English. Eduardo occupied different strategic points in the name of Monfort, while obtaining guardianship of his son and that of Juana de Flandes, who had gone mad. Eduardo practically dominated the affairs of the duchy at the end of 1345. The duchy was divided in two: Charles of Blois dominated to the French zone, Upper Brittany and Nantes, while the Monforts held Léon, Cornwall and almost all of Lower Brittany, positions each side held essentially throughout the succession war. This was fought through a series of sieges, single combat and disorganized skirmishes.

The truce of 1343 was renewed several times, but the failure of the parliaments of Avignon, in which the positions of the belligerents became clear (the English demand for an independent and grown Guyenne and the French refusal to cede the sovereignty of any territory of the kingdom) caused it to lapse in March 1345. Thomas Dagworth immediately launched an offensive into Brittany, seizing several cities. John de Monfort died in 1345, leaving Charles of Blois as the sole claimant to the ducal crown of Brittany. This fell into the hands of the enemy when he was trying to recapture the place of La Roche-Derrien in June 1347.

The French had naval superiority, thanks in part to Genoese mercenaries, which allowed the French fleet to repeatedly attack English ports. The French considered cutting off shipping connections between the Continent and Great Britain, in order to deprive England of wine from Guyenne and salt from Brittany and Poitou, of great importance to the enemy. They effectively interrupted the wool trade with Flanders and that of Bordeaux wine, which seriously damaged English finances.

Situation in Navarra

Philip IV and Carlos IV had been kings of Navarre as well as being kings of France; they administered the small Iberian kingdom through governors with wide powers. However, the assembly of rich men, knights and villains decided in 1328 to choose an heir different from the one chosen in Paris: it was unanimously decided to recognize Juana, the daughter of Luis, as queen. X postponed from the French succession in 1316, who was the wife of Felipe de Évreux, the frustrated claimant to the French throne. The proclamation was made on March 5, 1329 in Pamplona. The two kingdoms were formally separated as their sovereigns (they were cousins), but the Navarrese continued to be very interested in French politics. Felipe perished fighting the Algeciras in favor of Alfonso XI of Castile and Juana remained sovereign for the six years she survived her husband. Then the crown passed to Charles II of Navarre.

Scottish flop

Philip VI began to fear an English invasion of the kingdom, so he convinced the Scottish allies to attack England from the north, trusting that the concentration of the English armies in the south of the kingdom would have left the border almost defenseless northern. The Scottish offensive was also to serve to weaken the narrow siege to which Edward III was then subjecting Calais. David II undertook the invasion on 7 October 1346 at the head of twelve thousand men, surrounded Durham and reached a small nearby town, Neville's Cross. The Archbishop of York, in charge of the border defense, defeated and captured David at the Battle of Neville's Cross (17 October), imitating Crécy for the skilful use of of the archers. The Scottish king spent the next eleven years imprisoned in the Tower of London. The victory over the Scots left Edward III free to invade France without concern for the safety of the kingdom.

English riding and ineffective French defense

Eduardo III needed the support of the powerful and with it that of Parliament to sustain the contest. To earn it, he opted to undertake a series of vigorous offensives in France, despite the obvious population disadvantage between the two kingdoms (France had at that time about twenty million inhabitants, five times more than those that populated England). Faced with the power of the French cavalry, the English sovereign ruled out permanent conquests on the continent, which he would have had to defend against the enemy, thereby risking his reputation and perhaps his life. The various battles of the time were due fundamentally to the circumstances of the campaigns and not to a desire of the English monarch to confront the enemy so directly. Edward's strategy was, on the contrary, that of looting, which also allowed him to finance the expeditions. One of the most famous cavalcades of the time, the one that Eduardo embarked on in 1346, exemplifies this type of incursions: an army of small size, but capable of moving quickly, marched devastating everything in its path, without regard for the population of which it Edward claimed to be a legitimate sovereign.

Philip VI had some fifty thousand soldiers in 1347, just before the Black Death spread through the area, an army much larger than the enemy, partly due to the larger population of the kingdom. However, the English war strategy forced the French monarch to bear expensive defenses. For its part, the English army was mobilized for just a few months, and paid for its expenses thanks to looting. The capacity of the English fleet also limited the number of soldiers that could be sent to the Continent: Edward had between twenty and thirty thousand soldiers, but he took only half, albeit the best, with him to France. Felipe VI experimented with two defensive strategies unsuccessfully: the defense of castles and walled cities and the pursuit of the enemy. The first allowed the English to verify their raids while the French limited themselves to defending strongholds, cities or fortresses. This entailed considerable expenses in garrisons that were added to what was lost due to the English havoc in the fields and to the discredit that the king incurred for being passive. The second required the slow mobilization of a large army to pursue a swift enemy, who could choose when and where to meet the French and who often had time to clear the countryside before the pursuing army could rally.

Edward III's raids had several goals, not including taking over the neighboring kingdom. They had to undermine the authority of Felipe VI, evidencing his inability to defend the people and, in the long term, achieve full sovereignty of Guyenne, if possible expanded in territory; the relinquishment of the claim to the French crown in the Treaty of Brétigny demonstrated that Edward's interest lay more in the domain of Guyenne than in the entire kingdom.

First English rides (1339-1347): Crécy and Calais

Eduardo III's first cavalcade in France was made in 1339 with between ten thousand and fifteen thousand soldiers, of whom about one thousand six hundred were men-at-arms (heavy cavalry), one thousand five hundred mounted archers, one thousand six hundred and fifty horse archers. foot and eight hundred Dutch and Germans. The army advanced in three columns, covering between ten and twenty kilometers a day on a front about twenty kilometers wide, looking for the least protected cities. The army conscientiously cleared the territory it crossed, killing the cattle and destroyed production facilities such as mills and ovens. The ride that year devastated more than two hundred towns.

French raids on Bordeaux led Edward III to send the Earl of Derby and Walter de Mauny to defend it in 1345. They launched a swift campaign that took them to Angoulême. Another cavalcade penetrated into Languedoc. The heir of the French crown, John, Duke of Normandy, counterattacked in the spring of 1346 and, although he recovered some lost places, got bogged down before Aiguillon, which he failed to take before having to withdraw in August when news of the disaster suffered by his father in Crécy.