Hourglass

An hourglass is a mechanical instrument used to measure a certain period of time. It has two connected glass receptacles allowing a regulated flow of material, usually fine sand, from the top to the bottom, until it is completely emptied. The operation only requires the potential energy of gravity.

Once the top container is empty, it can be inverted to start timing again. Among the factors that influence the measured time are the quantity and quality of the sand, the size of the containers and the width of the neck. Although sources disagree on the best material, alternatives to sand include marble dust and powdered eggshell.

Since the period it measures is fixed, although with slight variations, it is a disused device, replaced by the wristwatch to know the time, and the stopwatch to measure the precise time elapsed between two events. In modern times, hourglasses are ornamental, or used when a rough measurement is sufficient, such as timers for cooking eggs or for board games.

History

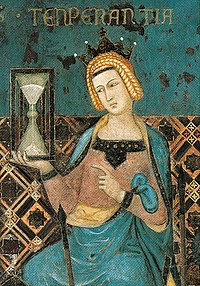

The origin of the hourglass is unclear, although it may have been introduced to Europe by a monk in the 8th century named Liutprando, who served in the cathedral of Chartres, France. It was not until the 14th century that the hourglass is commonly seen, the earliest evidence being a 1338 depiction of the fresco Allegory of Good Government by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Unlike its predecessor, the clepsydra, or water clock, it is believed that the sand originated in medieval Europe. This theory is based on the fact that the earliest written records of it were mostly from the logbooks of European ships. Written records from the same time mention the clock of sand, and that appears in the lists of provisions on board. An early record is a sales receipt from Thomas of Stetesham, secretary of the English ship The George, in 1345:

Thomas himself represents having paid in Lescluse, in Flanders, twelve horologist glass ("pro xii. Orlogiis vitreis"), the price of each article 41⁄2 gross ', in sterling pounds 9' of . By four horologists of the same class ("de eadem secta"), he bought there, the price of every five bruta ', so in pounds sterling 3' of . 4d. "

Hourglasses were very popular on ships, being the most reliable measure of time at sea. Unlike the hourglass, the movement of the ship during navigation did not affect the hourglass. The fact that the hourglass uses granular materials rather than liquids led to more accurate measurements, as the hourglass was prone to condensation on its interior during changes in temperature. Mariners found the hourglass capable of to help them determine longitude, the distance east or west from a certain point, with reasonable accuracy.

The hourglass found popularity on land as well. As the use of mechanical clocks to indicate the times of events such as religious services became more common, the creation of a need to keep track of time increased the demand for time-measuring devices. Hourglasses were essentially inexpensive, since they did not require any sophisticated technology to manufacture and their contents were not hard to come by, and, as the manufacture of these instruments became more common, their use became more practical.

Hourglasses were commonly used in churches, homes, and workplaces to measure sermons, cooking times, and time spent on work breaks. Because they were being used for more mundane tasks, the model of the hourglass began to decrease. The smaller models were more practical and very popular but above all more discreet.

After 1500, the hourglass was no longer as widespread. This was due to the development of the mechanical clock, which became more accurate, smaller, and cheaper, and made it easier to measure time. The hourglass, however, did not disappear entirely. Although it became relatively less useful with the advanced technology of mechanical watches, hourglasses continued to exist due to their design. Some of the most famous hourglasses are the twelve-hour hourglass of Charlemagne of France and the hourglasses of Henry VIII of England, made by the artist Holbein in the 18th century XVI. The oldest known hourglass is in the British Museum in London.

It was not until the 18th century that the Harrison brothers, John and James, put into operation the first marine clock in high precision that significantly improved with the stability of the hourglass at sea. Taking elements of the design logic behind the hourglass, they were able to create a marine chronometer capable of accurately measuring the voyage from England to Jamaica, to within five seconds of miscalculation, in 1761.

Design

There is almost no written evidence as to why the external shape of the hourglass is the way it is. Used glass bulbs, however, have changed in style and design over time. While the main designs have always been blister-shaped, the bulbs weren't always connected. The first hourglasses consisted of two separate bulbs with a wire wound around their junction, which was then coated with wax to hold the two pieces together and allow sand to flow in between. It was not until 1760 that both bulbs they were blown together to keep moisture out of them and to regulate the pressure inside the bulb that varied the flow.

Materials

While some hourglasses actually made use of sand as the granular mixture to measure time, many did not use sand at all. The material used in most of the bulbs consisted of a combination of "dust, oxides of marble, tin/lead, and pulverized and burned eggshell". Over time, the different textures of the material granular were being tested to determine which provided the most constant flow within the bulbs. It was later discovered that to achieve perfect flow, the ratio of granule to bulb neck width should be 1:12 or more, but not more than 1:2 relative to the bulb neck.

Practical uses

Hourglasses were a reliable, reusable and precise instrument. The flow rate of the sand is independent of depth in the upper reservoir, and the instrument does not freeze in cold weather.

From the 15th century onwards, hourglasses are used in a variety of applications at sea, in the church, in the industry and in the kitchen. During Ferdinand Magellan's voyage around the world, each of his ships carried 18 hourglasses. One of the ship's pages was in charge of turning each clock around, in order to provide the times for the logbook. The reference time for the ship was noon, a time that does not depend on the hourglass because the sun is at its zenith. A frame is sometimes used to support several hourglasses, each with a different duration, for example 1 hour, 45 minutes, 30 minutes, and 15 minutes.

Modern practical uses

Although they are no longer widely used to keep track of time, some institutions still maintain them. For example, the two houses of the Australian Parliament use three hourglasses to divide time in certain procedures.

The hourglass is still widely used in the kitchen; for cooking eggs, a three-minute timer is typical.

The hourglass is also sometimes used in games like Pictionary and Boggle to enforce a time constraint on game rounds, and to provide a sense of urgency to the game of Quicksand.

Symbolic uses

Unlike most other methods of measuring time, the hourglass specifically represents present time as existing between the past and future, and this has made it an enduring symbol of time itself.

The hourglass, sometimes with the addition of metaphorical wings, is often depicted as a symbol that human existence is ephemeral, that "the sands of life have passed by". It was therefore used in pirate flags to strike fear into the hearts of its victims. In England, hourglasses were sometimes placed inside coffins, and engravings have appeared on headstones for centuries. The hourglass was also used in alchemy as a symbol of the hours.

The First Metropolitan Borough of Greenwich in London uses an hourglass on its coat of arms, symbolizing Greenwich's role as the origin of GMT. The borough's successor, the Royal Borough of Greenwich uses two hourglasses on its coat of arms.

Modern Symbolic Uses

The hourglass as a symbol of time has outlived its obsolescence as a timekeeper. For example, the American soap opera Days of our Lives, since its first broadcast in 1965, has shown an hourglass in its opening credits, accompanied by the words "Like the sand through the clock." Such are the days of our lives," delivered by Macdonald Carey.

In the graphical user interface of computers, it is common for the pointer to turn into an hourglass during a period when the program is in the middle of a task and cannot accept user input. During that period, other programs, for example, in different windows, can work normally. The fact that such an hourglass does not disappear suggests that a program is in an infinite loop and must be terminated, or is waiting for an external action from the user (such as inserting a CD). Unicode has a symbol called HOURGLASS in U+231B(⌛).

Contenido relacionado

Circular particle accelerator

Van Allen Belts

Magnetic domain