Homeopathy

Homeopathy (from the Greek ὅμοιος [hómoios], 'same', and πάθος [páthos], 'disease') is a system of alternative medicine created in 1796 by Samuel Hahnemann based on his doctrine of "like cures like" (similia similibus curentur), which holds that a substance that causes the symptoms of a disease in healthy people it will cure the similar in sick people. Homeopathy is a pseudoscience: a belief that is falsely presented as science. Homeopathic preparations are not effective in treating any disease, so should also be designated as pseudotherapy. Large-scale studies have shown that homeopathic products are no more effective than placebos, indicating that any subsequent positive feelings to treatment is only due to the placebo effect and normal recovery from the disease.

Hahnemann believed that the underlying causes of disease were phenomena he called miasmas and that homeopathic remedies acted on them. These are prepared by successive dilutions of the chosen substance in alcohol or distilled water, followed by a forceful blow to an elastic body (usually a leather-bound book). Usually the dilution continues well beyond the point where no molecules of the original substance.Homeopaths select preparationsby consulting reference books known as repertoires and considering the totality of the patients' symptoms, personality traits, physical and psychological state, and life history.

Homeopathy is not a credible treatment system, since its dogmas about how medicines, disease, the human body, liquids and solutions work have been refuted by a large number of discoveries from the fields of biology, psychology, physics, and chemistry conducted in the two centuries after its invention. Although some clinical trials produce positive results, multiple systematic reviews reveal that they are due to chance, flawed research methods, and reporting bias. The persistence of homeopathic practice, despite evidence that it does not work, has been criticized as unethical on the grounds that it discourages the use of effective treatments, and the World Health Organization has warned against its use to treat serious illnesses such as AIDS or malaria. The insistence on its use, despite the lack of evidence on its efficacy, has led it to be characterized within the scientific and medical communities as nonsense, quackery or sham.

There have been four major evaluations of homeopathy by national and international bodies: the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the UK House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, and the Federal Office of Health Swiss Public. They have each concluded that homeopathy is ineffective and advised against continuing its funding. The British National Health Service (NHS) announced a policy of not funding homeopathic medicine as it is a "misuse of resources". They asked the Department of Health to add homeopathic remedies to the blacklist of prohibited prescription items, and the NHS ceased funding for homeopathic products in November 2017.

History

Historical context

Homeopaths claim that Hippocrates may have originated homeopathy around 400 B.C. C. when he prescribed a small dose of mandrake root to treat mania, knowing that it produces it in much larger doses. In the century 16th century, the pioneer of pharmacology Paracelsus declared that small doses of "what makes a man ill also cures him". Samuel Hahnemann (1755-1843) gave his name to homeopathy and expanded its beginnings at the end of the XVIIIth century. At that time, the dominant medicine - today called "heroic medicine" - used methods such as bloodletting and purgation, and administered complex mixtures, such as the Venetian theriac, which was composed of 64 substances, including opium, myrrh and snake meat. These treatments often worsened symptoms and were sometimes fatal. Hahnemann rejected these practices, which had been praised for centuries, as irrational and inadvisable; instead, he advocated the use of single medications at smaller doses and argued an immaterial and vitalist view of how living organisms function, as he believed that illnesses had spiritual as well as physical causes.

Hahnemann's concept

The term "homeopathy" it was coined by Hahnemann and first published in 1807.

Hahnemann conceived of homeopathy while translating a medical treatise by Scottish physician and chemist William Cullen into German. Skeptical of Cullen's theory regarding the use of cinchona to cure malaria, Hahnemann ingested his bark alone to find out what would happen. He experienced fever, chills and joint pain: symptoms similar to those of malaria. From this, he came to believe that all effective drugs produce in healthy individuals symptoms similar to those of the diseases they treat, in accordance with the "law of similars"; that ancient physicians had proposed. A report published in 1861 on the effects of eating cinchona bark by Oliver Wendell Holmes failed to reproduce the symptoms that Hahnemann stated. Hahnemann's law of similars is a postulate rather than a law scientific.

Subsequent scientific works showed that cinchona cures malaria because it contains quinine, a substance that kills the parasite that causes the disease (Plasmodium falciparum). Its mechanism of action is not related to the symptoms of cinchonism.

"Checks"

Hahnemann began to examine what effects each substance produced in man, a procedure that would later be known as "homeopathic testing." These examinations required subjects to assess the effects of substance ingestion by clearly recording all their symptoms, plus secondary illnesses along with those that occurred. He published a collection of proofs in 1805 and a second with 65 remedies was included. in his book Pura Materia Medica (1810).

Because Hahnemann believed that high doses of drugs that caused similar symptoms would only aggravate the disease, he advocated extreme dilutions. He devised a technique for preparing solutions that he believed would preserve the therapeutic properties of the substance while removing its ill effects. He believed that the process awakened and increased "the spirit-like medical powers of crude substances". He assembled and published a comprehensive summary of his new medical system in his book Organon of the Art of Healing (1810), the sixth edition of which, written in 1842 and published posthumously in 1921, is still used by homeopaths today..

Miasmas and disease

In Organon of the Art of Healing, Hahnemann introduced the concept of "miasmas" as "infectious principles" underlying chronic diseases.He associated each miasm with specific diseases and thought that initial exposure to the miasms causes local symptoms, such as skin or venereal diseases. However, if these symptoms were suppressed by medication, the cause would penetrate and begin to manifest itself in diseases of the internal organs. Homeopathy holds that the treatment of diseases by relieving their symptoms, which is sometimes done in scientific medicine, is ineffective because all "diseases can usually be traced to some latent, deep-seated, underlying chronic or inherent tendency". the inner disturbance of the life force.

Hahnemann originally postulated only three miasms, of which the most important was psora (Greek for 'itching'), described as being related to any itchy skin disease, supposedly coming from the suppression of scabies, and claimed that it was the basis of many other diseases. He believed that psora was the cause of diseases such as epilepsy, cancer, jaundice, deafness, and cataracts. Since Hahnemann's time, other miasms have been proposed, some of which replace one or more functions proposed for psora. psora, including tuberculosis miasm and cancer miasm.

The law of susceptibility implies that a negative mindset can attract hypothetical diseased entities called "miasmas" to invade the body and produce the symptoms of diseases. Hahnemann rejected the notion that a disease is an independent or invading entity, insisting that it was always part of the "whole organism". He coined the expression "allopathic medicine", which was used pejoratively to refer to traditional Western medicine.

His theory of miasms remains disputed and controversial within homeopathy even today. The miasm theory has been criticized as an explanation developed by Hahnemann to preserve the system of homeopathy against therapeutic failures and for being inadequate to cover the several hundred classes of disease, and for failing to explain predispositions to disease. genetics, environmental factors and the unique medical history of each patient.

19th century: leap to popularity and early criticism

Homeopathy reached its greatest popularity in the 19th century. It was introduced to the United States in 1825 by Hans Birch Gram, a student of Hahnemann's. The first homeopathic school in the United States opened in 1835 and the first national medical association in the United States, the American Institute of Homeopathy, was established. in 1844. Through the 19th century, dozens of homeopathic institutions sprang up in Europe and the United States. By 1900, there were 22 homeopathic schools and 15,000 practitioners in the United States alone. Because medical practice at the time was based on ineffective and often dangerous treatments, patients of homeopaths often fared better than those of physicians at the time Homeopathic remedies, though ineffective, would almost certainly cause no harm, so users of homeopathy were less likely to die from the treatment that was supposed to improve them. The relative success of homeopathy in the 19th century may have led to the abandonment of the ineffective and noxious treatments of bloodletting and purgation and started the trend towards more effective and scientific medicine. One reason for its rise was its apparent success in treating patients with infectious epidemics. During the epidemics of the century XIX, like cholera, case fatality rates were often lower in homeopathic hospitals than in conventional hospitals, where current treatment was often harmful and had little or no effect in combating disease.

From its inception, however, homeopathy was criticized by the scientific community. Sir John Forbes, Queen Victoria's physician, said in 1843 that extremely small doses of homeopathy were often ridiculed as useless, "an outrage on human reason". James Young Simpson said in 1853 about them: "No poison, however strong or powerful, in its billionth or quintillionth part could in any degree affect man or harm a fly." Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., physician and American author of the 19th century who was also a public critic of homeopathy and published an essay titled Homœopathy and Its Kindred Delusions (1842, Homeopathy and Its Similar Delusions). In 1867, members of the French Society of Homeopathy noted that some of Europe's leading homeopaths were not only abandoning the practice of administering infinitesimal doses, but were they no longer defended them either. The last American school of Dedicated exclusively to the teaching of homeopathy, it closed in 1920.

Renaissance in the 20th century

According to Paul Ulrich Unschuld, the Nazi regime in Germany was fascinated with homeopathy and spent large sums of money to investigate its mechanisms, but without achieving a positive result. Unschuld added that homeopathy did not take root again in the United States, but remained more entrenched in European thought.

In the United States, the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 (proposed by Royal Copeland, Senator from New York and homeopathic physician) recognized homeopathic remedies as medicines. In the 1950s, there were only 75 purely homeopathic practitioners in the country. However, in the second half of the 1970s, homeopathy resurfaced and sales of some homeopathic companies increased tenfold. Some homeopaths credit it with his revival to Greek homeopath George Vithoulkas, who did "a great deal of research to update the settings and refine the theories and practices of homeopathy" since that decade, but Ernst and Singh consider it to be associated with the rise of the New Age movement. Whatever the reason, the pharmaceutical industry recognized the commercial potential of selling homeopathic remedies.

Bruce Hood has argued that the recent rise in his popularity may be due to the comparatively long consultations that homeopaths give their patients and an irrational preference for 'natural' products, which the public thinks is the basis of homeopathic remedies.

Remedies and treatment

Practicers of homeopathy rely on two types of references to prescribe remedies: materia medica and repertoires. A homeopathic materia medica is a collection of "remedy profiles", arranged alphabetically by "remedy". These entries describe the symptom patterns associated with individual remedies. While a homeopathic directory is an index of disease symptoms that lists the remedies associated with specific symptoms.

Homeopathy uses various substances of animal, vegetable and synthetic origin in its preparations. For example, arsenicum album (arsenic oxide), natrum muriaticum (sodium chloride, table salt), Lachesis muta (the poison dumb rattlesnake), opium (opium) and thyroidinum (thyroid hormone). Additionally, homeopaths use treatments called "nosodes" (Greek noso, disease) made from infected material or pathological products such as fecal, urinary, and respiratory secretions, blood, and tissues. Homeopathic remedies prepared from healthy specimens are called "sarcodes& #3. 4;.

Some modern homeopaths have considered more esoteric bases for the preparation of remedies, known as "imponderables" because they do not originate from a substance, but from an electromagnetic energy that was supposedly "captured" in alcohol or lactose. Examples include X-rays and sunlight. Some homeopaths also use techniques that are considered by other practitioners to be controversial. These include "paper remedies," in which the substance and solution are written on pieces of paper and clipped to the patient's clothing, kept in their pocket, or placed under glasses of water that given to patients, in addition to the use of radionics to prepare remedies. Such practices have been heavily criticized by classical homeopaths as unfounded, speculative, and bordering on magic and superstition.

Preparation

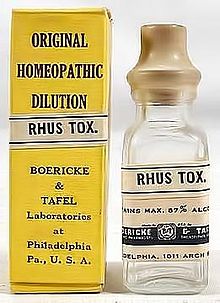

In producing remedies for disease, homeopaths use a process called "dynamization" and "potentiation," where a substance is diluted with alcohol or distilled water and then vigorously agitated by 10 hard blows against an elastic body, a process they call "succussion." the use of substances that produced symptoms similar to those of the disease being treated, but found that undiluted doses intensified symptoms and exacerbated, sometimes causing dangerous toxic reactions. For this reason, he specified that the substances be diluted, due to his belief that the succussion activated the & # 34; vital energy & # 34; of the diluted substance and made it stronger. To facilitate the succussion, Hahnemann had a saddle craftsman construct a special wooden striking plank covered in leather on one side and stuffed with horsehair. Insoluble solids, such as granite or platinum, are diluted by grinding them with lactose ("shredding").

Dissolutions

There are three common logarithmic potency scales in homeopathy. Hahnemann created the centesimal scale or 'C scale', diluting a substance by a factor of 100 at each stage. This was Hahnemann's favorite for most of his life. A 2C solution requires that a substance be diluted to one part in a hundred and then one part of this solution be diluted again by the same factor. This results in a preparation with one part parent substance per 10,000 parts solution. A 6C solution repeats the process six times, ending with the parent substance diluted by a factor of 100−6=10−12 (one part in a trillion or 1/1,000,000,000,000). Larger solutions follow the same procedure. In homeopathy, a more dilute solution is described as having a greater potency and more dilute substances are considered by homeopaths to be stronger, deeper-acting remedies. Often the final preparation is so dilute that it is indistinguishable from the diluent (pure distilled water, sugar, or alcohol). There is also a scale of decimal potency (noted as X or D) in which the remedy is diluted by a factor of 10 at each stage.

Hahnemann advocated 30C preparations for most purposes (i.e., 1060 factor dilution). In his time, it was reasonable to assume that remedies could be diluted indefinitely, since that the concept of an atom or molecule as the smallest unit of a chemical substance was just beginning to be known. We now know that the largest solution in which it is reasonably likely to find at least a single molecule of the parent substance is 1024 (12C in homeopathic notation).

Both critics and defenders of homeopathy usually try to illustrate the solutions used in homeopathy with analogies. Hahnemann is said to have joked that a proper procedure for dealing with an epidemic would be to empty a bottle of poison into Lake Geneva, if it could succuss itself 60 times. Another example is the equivalence of a 12C solution to a "pinch of salt in the North and South Atlantic Oceans", which is roughly correct. One-third of a drop of the original substance diluted in all the waters on Earth would produce a remedy with a concentration of about 13C. A popular homeopathic remedy for flu is a 200C solution of duck liver, marketed under the trade name Oscillococcinum. Since there are about 1080 atoms in the entire observable universe, a dissolution of a molecule in the entire universe would be around 40C. Oscillococcinum would therefore require an extra 10320 universes to preserve just a single molecule in the final product. It is for these reasons that the high solutions, in typical use, are considered the most controversial and implausible aspect of homeopathy.

Not all homeopaths advocate extremely high dilutions. Remedies of potencies below 4X are considered an important part of the homeopathic heritage. Many of the early homeopaths were originally physicians and generally used low solutions such as 3X or 6X and rarely went beyond 12X. The separation between low and high solutions was derived from ideological attitudes. Those who preferred low dilutions emphasized pathology and a strong link to conventional medicine, while those who preferred high dilutions emphasized life force, miasms, and a spiritual interpretation of disease. Some products with such relatively low dilutions they continue to be sold, but like their tall counterpart, they have not been shown to have an effect greater than a placebo.

“Checks”

A homeopathic check is the method by which the profile of a homeopathic remedy is determined.

Initially Hahnemann used undiluted doses for the procedure, but later advocated those with 30C remedies, while most modern testing is done with ultra-diluted preparations where it is highly unlikely to find even a single original molecule. During the testing process, Hahnemann administered remedies to healthy volunteers and the resulting symptoms were collected by observers into a "remedy profile." Volunteers were observed for months and made to write extensive diaries detailing their symptoms and the time of onset throughout the day. They were prohibited from consuming coffee, tea, spices or wine for the duration of the check, as well as from playing chess because Hahnemann considered it 'too exciting', although they could drink beer and moderate exercise was encouraged. After the experiment was over, Hahnemann made them swear they had written the truth and questioned them extensively about their symptoms.

Tests have been described as important in clinical trial development, due to their early use of control groups, simple quantitative and systematic procedures, and one of the earliest applications of statistics to medicine. Homeopaths' records of self-experiment have been useful in the development of modern medicines: for example, evidence that nitroglycerin might be useful in the treatment of angina was discovered by reading homeopathic proofs, although homeopaths themselves never previously used it for this purpose. The first record of proofs was published by Hahnemann in Essay Concerning a New Principle (1796). His Fragmenta de Viribus (1805) contains the results of 27 proofs and his Pura Materia Medica (1810) has 65. For Lectures on Homoeopathic Materia Medica (1905) by James Tyler Kent, 217 substances were tested and new ones are continually added to contemporary versions.

Although the testing procedure bears superficial similarities to clinical trials, it is fundamentally different in that the process is subjective, not blind, and modern testing is unlikely to have pharmacologically active levels of the substance to be tested. In 1842, Holmes observed that the tests were extremely vague and the supposed effects of the substances were not repeated between the different subjects.

Exam and repertoires

Homeopaths generally begin with detailed examinations of their patients' histories, including questions about their physical, mental, and emotional state, their life circumstances, and any other physical or emotional illnesses. They then try to translate it into a complex formula of physical and mental symptoms, including likes, dislikes, and inborn predispositions and even blood type.

From this data, the homeopath chooses how to treat the patient. A compilation of reports on various homeopathic proofs, supplemented by clinical data, is known as homeopathic "materia medica. But because the practitioner needs to first explore the remedies for a particular symptom rather than look up the symptoms for a certain remedy, the "homeopathic repertoire" is the only way to go. (an index of symptoms) lists next to each symptom the remedies associated with it. Directories are often very extensive and may include information drawn from multiple sources of materia medica. There is often a heated debate between directory compilers and practitioners about the veracity of any particular listing.

The first symptomatic index of the homeopathic materia medica was composed by Hahnemann. Soon after, one of his students, Clemens von Bönninghausen, created the Pocket Therapeutic Book, another homeopathic directory. The first such directory was Symptomenkodex (1835) by Georg Jahr, published in German and the first repertory to be translated into English (1838) by Constantine Hering as Repertory to the more Characteristic Symptoms of Materia Medica ). This version focused less on disease categories and would be the forerunner of Kent's later works. It consists of three large volumes. Such repertoires increased in size and detail over time.

There is some diversity in therapeutic approach among homeopaths. The "classic homeopaths" they generally resort to detailed examination of the patient's history and changing doses of a single remedy while the patient is observed for improvements in her symptoms. On the other hand, "clinical homeopaths" they use combinations of remedies to prescribe different symptoms of a disease.

Pills

Homeopathic pills are made of an inert substance (often sugar, typically lactose) infused by a drop of a homeopathic preparation.

Homeopathy is about making extreme dilutions and once made they sprinkle on a sugar pill. If you look at the composition is sugar, if you look at its price, it seems that Fidel Castro himself has gone to cut the cane.José Miguel Mulet

'Active' Ingredients

The list of labeled ingredients on remedies can mislead consumers into believing that the product actually contains those ingredients. In accordance with normal homeopathic practice, remedies are prepared starting with an active ingredient that is repeatedly diluted to the point where the final product no longer contains any biologically "active" ingredients, as the term is usually defined.

James Randi and the 10:23 Campaign have demonstrated the absence of active ingredients in homeopathic products by taking large 'overdoses'. None of the hundreds of protesters in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US suffered no harm as a result of its excessive intake and "none were cured of anything either".

While the absence of active components is noted in most homeopathic products, there are some exceptions such as Zicam Cold Remedy, which is marketed as an "unapproved homeopathic" for colds. It contains a number of highly diluted ingredients that are listed as "active ingredients" In the label. Some of the homeopathic ingredients used in its preparation are galphimia glauca (red arnica), histamine dihydrochloride (homeopathic name histaminum hydrochloricum ), luffa operculata and sulfur. Although the product is sold as "homeopathic," it contains two ingredients that are only "slightly" Diluted: Zinc Acetate (2X dilution = 1%) and Zinc Glucanate (1X = 10%), which means that both are present in concentrations that contain biologically active ingredients. In fact, they are strong enough to have caused some people to lose their sense of smell, a condition called anosmia. Because Zicam's manufacturers labeled it as a homeopathic product (despite the relatively high concentrations of active ingredients), it is exempt from FDA regulations under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994.

Related practices and treatments

Isopathy

Isopathy is the derivative therapy of homeopathy created by Johann Joseph Wilhelm Lux in the 1830s. It differs from homeopathy in that the remedies, known as "nosodes," are made of either things that cause disease, either from products of the disease, such as pus. Many so-called "homeopathic vaccines" they are a form of isopathy.

Flower Remedies

Flower remedies can be made by placing flowers in water and exposing them to sunlight. The most famous are the Bach flower remedies, developed by the physician and homeopath Edward Bach. Although proponents of these remedies share his vitalist view and claim that the remedies work through the same presumed "vital force" from homeopathy, differ in the method of preparation. Bach remedies are prepared in 'kinder' ways: water is placed in sunlit bowls and the remedies are not succussed. There is no convincing scientific or clinical evidence that Bach herbal remedies be effective.

Veterinary use

The idea of using homeopathy as a treatment for animals or "veterinary homeopathy" it dates its very inception: Hahnemann himself wrote and spoke about the use of homeopathy in animals other than humans. The FDA has not approved homeopathic products in veterinary medicine in the United States. In the UK, veterinarians using homeopathy must be members of the Faculty of Homeopathy and/or the British Association of Homeopathic Veterinary Surgeons. Animals can only be treated by qualified veterinarians in the UK and other countries. Internationally, the body that supports and represents homeopathic veterinarians is the International Association for Veterinary Homeopathy.

The use of homeopathy in veterinary medicine is controversial. The little existing research on it is not up to the scientific standard to provide reliable information on its efficacy. Other studies have also found that giving placebos to animals can play an active role in influencing owners to believe in the effectiveness. of treatment where none exists. The British Veterinary Association's position on alternative medicines is that it "cannot endorse" homeopathy and the Australian Veterinary Association includes it on its list of "ineffective therapies".

The UK Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DeFRA) has taken a strong position against the use of "alternative" for pets, including homeopathy.

Electrohomeopathy

Electrohomeopathy is a treatment created by Count Cesare Mattei (1809-1896), who proposed that different "colors" of electricity could be used to treat cancer. Popular in the late 19th century, electrohomeopathy has been described as "total idiocy".

Evidence and efficacy

The low concentration of homeopathic remedies, often lacking even a single molecule of the parent substance, has been the basis of questions about their effects since the century XIX. Contemporary proponents of homeopathy have proposed the concept of "water memory," according to which water "remembers" the substances mixed in it and transmits the effects of those substances when consumed. This concept is inconsistent with the current understanding of the matter and water memory has never been shown to have any detectable effect, biological or otherwise. To the contrary, pharmacological research has found that the greatest effects of an active ingredient come from higher doses, not lower ones.

Outside the complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) community, scientists have long considered homeopathy a sham or pseudoscience and the medical community considers it quackery. There is a general lack of statistical evidence of their therapeutic efficacy, which is consistent with the lack of any biologically plausible pharmacological agent or mechanism. Abstract concepts from theoretical physics have been invoked to suggest explanations for how or why the remedies might work, including quantum entanglement, quantum non-localization, the theory of relativity and the theory of chaos. However, the explanations are proposed by laymen in the field and often include speculation with incorrect conceptual uses, as well as not being really supported by experimentation. Several of the key concepts of homeopathy are in conflict with fundamental concepts of physics and chemistry. The use of quantum entanglement to explain purported homeopathic effects is "patent nonsense", as entanglement is a fragile state that rarely lasts longer than a fraction of a second. On the other hand, while this property can cause certain aspects of individual subatomic particles to acquire quantum bound states, this does not mean that the particles mirror or duplicate each other, nor does it cause health-enhancing transformations.

Plausibility

The mechanisms proposed for homeopathy are prevented from having any effect due to the laws of physics and medicinal chemistry.

Extreme dilutions used in homeopathic preparations often leave none of the original substance in the final product. The modern mechanism proposed by homeopaths, water memory, is considered erroneous because the short-range order of water only persists for about 1 picosecond (1 × 10–12 s). The existence of pharmacological effects in the absence of any authentic active ingredient is inconsistent with the observed dose-response relationship characteristic of drugs (whereas the placebo effect is non-specific and unrelated to pharmacological activity). The rationale proposed for these extreme dilutions, that water has the "memory" or "vibration" of the diluted ingredient, is contrary to the laws of chemistry and physics, such as the law of mass action.

Extreme dilution

Extreme dilutions of homeopathy preclude the possibility of a biologically plausible mechanism of action. Often their remedies are diluted to the point where no original molecules are left in a dose of the final product. Homeopaths argue that the methodical dilution of a substance, starting with a 10% solution or less and working down, always stirring after each dilution, produces a therapeutically active remedy, in contrast to inert water. Because even the longest-lived noncovalent structures in liquid water at room temperature are stable for only a few picoseconds, critics have concluded that any effect the original substance might have had can no longer persist. evidence of clusters of water molecules when studying homeopathic remedies using nuclear magnetic resonance.

Moreover, since water has been in contact with millions of different substances throughout its history, critics point out that water is therefore an extreme dilution of almost every conceivable substance. By drinking water, according to homeopathic interpretation, one would receive treatment for every imaginable disease. Compare ISO 3696:1987, this defines a standard for water used in laboratory analysis and allows a contamination level of ten parts per billion, 4C in homeopathic notation. This water cannot be stored in glass containers, as contaminants would be released into the water.

Practices of homeopathy maintain that higher dilutions, described as higher potency, produce stronger medical effects. This idea is inconsistent with the dose-response relationship of conventional drugs, where Effects depend on the concentration of the active ingredient in the body. This relationship has been confirmed in a myriad of experiments in organisms as diverse as nematodes, rats, and humans.

Physicist Robert L. Park, former executive director of the American Physical Society, said, "Because the smallest amount of substance in a solution is one molecule, a 30C solution would have to have at least one molecule of the original substance in it." dissolved in a minimum of 1 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 [1060] molecules of water. This would require a container more than 30,000,000,000 times the size of the Earth". supposedly present in 30X pills, it would be necessary to take about two billion of them, which would total about a thousand tons of lactose plus all the impurities that lactose contains."

The laws of chemistry express that there is a limit of dilution without the complete loss of the original substance. This limit, identified with Avogadro's number, is approximately equal to the homeopathic potencies of 12C or 24X (1 part in 1024). Scientific tests carried out by the BBC programs Horizon and ABC's 20/20 were unable to differentiate the homeopathic dilutions of tap water, even when tests proposed by homeopaths themselves were used.

Efficiency

Not a single preparation has been shown to be unequivocally different from placebo. The methodological quality of the primary research was generally low, with problems such as flaws in study design and reporting, small sample sizes, and selection bias. Since higher-quality trials have been published, evidence for the efficacy of homeopathic preparations has diminished: higher-quality evidence suggests that homeopathic remedies themselves have no intrinsic effect. A 2010 systematic review of all relevant "best evidence" studies conducted by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that "the most reliable evidence – that from Cochrane reviews – fails to show that homeopathic medicines have effects beyond placebo".

Publication bias and other methodological issues

The fact that individual randomized controlled trials have shown positive results is not contradicted by the overall lack of statistical evidence of efficacy. A small proportion of clinical trials inevitably provide false-positive results due to the role of chance: a "statistically significant" positive result is normally adjudicated when the probability that it is due to chance rather than actual effects is no more than 5%; level at which 1 in 20 trials can be expected to show a positive result in the absence of therapeutic effects. In addition, trials of low methodological quality (for example, those with inappropriate design, conduct, or reporting) are prone to misleading results. In a systematic review of the methodological quality of randomized trials in three branches of alternative medicine, Linde et al. highlighted serious flaws in the homeopathic industry, including poor randomization.

A related problem is publication bias: on the one hand, researchers tend only to present trials with positive results, while on the other, journals prefer to publish positive results. Publication bias has been especially pronounced. in complementary and alternative medicine journals, where few of the published articles (only 5% during 2000) tend to report null results. Regarding the way homeopathy is presented in the medical literature, a systematic review found signs of bias in clinical trial publications (referring to negative representation in major medical journals, and vice versa in complementary and alternative medicine journals), but not in reviews.

Positive results are much more likely to be false if the preliminary probability of the statement under test is low.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Both meta-analyses, which statistically combine the results of several randomized controlled trials, and other systematic reviews of the literature are essential tools for summarizing the evidence on therapeutic efficacy. Early systematic reviews and meta-analyses of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of homeopathic remedies compared to placebo tended more often to yield positive results, but showed an unconvincing total. In particular, statements from three large meta-analyses warned readers that firm conclusions could not be reached, mainly due to methodological errors in primary studies and difficulty controlling for publication bias. The positive conclusion of one of the most prominent early meta-analyses, published in The Lancet in 1997 by Linde et al., was later reworked by the same research team, who wrote:

The evidence of bias [in primary studies] weakens the conclusions of our original meta-analysis. Since we completed our literature search in 1995, a significant number of new homeopathic trials have been published. The fact that several of the new high-quality trials [...] have negative results, and a recent update of our review of the more "original" (classical or individualized homeopathy), seems to confirm the conclusion that more rigorous trials have less promising results. It seems, therefore, likely that our metaanalysis at least overestimated the effects of homeopathic treatments.

Subsequent study by John Ioannidis and others have shown that for treatments without prior likelihood, the chances of a positive result being a false positive are much higher and that any result consistent with the null hypothesis should be assumed to be a false one. positive.

In 2002, a systematic review of available systematic reviews confirmed that higher-quality trials tended to have fewer positive results and found no convincing evidence that homeopathic remedies exert different clinical effects than placebo.

In 2005, the medical journal The Lancet published a meta-analysis of 110 homeopathy trials and 110 conventional medicine counterpart trials, both placebo-controlled, in the framework of the Homeopathy Evaluation Program. (PEK) of the Swiss government. The study concluded that its findings are "compatible with the notion that the clinical effects of homeopathy are placebo effects".

A 2006 meta-analysis of six trials that assessed whether homeopathic treatments could reduce the side effects of cancer therapy from radiation therapy and chemotherapy found that there was "insufficient evidence to support the clinical efficacy of homeopathic therapy in cancer care." cancer".

A 2007 systematic review of homeopathy for children and adolescents found that the evidence for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and childhood diarrhea was mixed. No difference compared to placebo was found for adenoid hypertrophy, asthma, or upper respiratory tract infection. The evidence was not sufficient to recommend any therapeutic or preventive intervention, and delay in medical care may be harmful to the patient.

In 2011, a systematic review of 25 trials that had tested homeopathy for psychiatric illnesses found no evidence of its effect for most illnesses and noted that the quality of the primary studies was in any case too poor to draw any conclusions about its safety or effectiveness.

The Cochrane Library found insufficient clinical evidence to assess the efficacy of homeopathic treatments for asthma, dementia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or labor induction. Other researchers found no evidence that Homeopathy is beneficial for osteoarthritis, migraines, delayed-onset muscle soreness, or eczema.

There have been several clinical trials that have put individualized homeopathy to the test. A 1998 analysis found 32 trials meeting the inclusion criteria, 19 of which were placebo controlled and provided sufficient information for a meta-analysis. These 19 studies showed pooled odds ratios of 1.17 to 2.23 in favor of individualized homeopathy over placebo, but no difference was observed when analysis was limited to evidence with better methodology. The authors concluded that “the results of the available randomized trials suggest that individualized homeopathy has an effect over placebo. The evidence, however, is not convincing due to methodological shortcomings and inconsistencies." Jay Shelton, author of a book on homeopathy, stated that it is assumed without evidence that individualized homeopathy works better than non-classical variations.

In a 2012 article published in Skeptical Inquirer, Edzard Ernst reviewed the publications of the research group that has published the majority of clinical studies of homeopathic treatment between 2005 and 2010. In a total of 11 articles, published in both conventional and alternative medicine journals, describing three randomized clinical trials (one article), prospective cohort studies without control groups (seven articles) and comparative cohort studies with controls (three articles).. The diseases include a wide range of conditions from knee surgery, eczema, migraine, insomnia to "any condition of elderly patients". Ernst's evaluations found numerous errors in design, direction, and reporting. Examples include poor detail of actual homeopathic treatment, misleading presentation of controls (comparison of homeopathic plus conventional treatment versus conventional treatment, but presented as homeopathic versus conventional treatment), and similar data in multiple articles. He concluded that misinterpretation of weak data made it appear that homeopathy has clinical effects, which can be attributed to bias or confounding and that the "casual reader may be seriously misled."

Statements by medical organizations

Organizations such as the UK's National Health Service, the American Medical Association, FASEB, and Australia's National Health and Medical Research Council have concluded that "good-quality evidence does not exist that homeopathy is effective as a treatment for any health problem'. In 2009, World Health Organization official Mario Raviglione criticized the use of homeopathy to treat tuberculosis; similarly, another WHO spokesperson argued that there was no evidence that homeopathy was an effective treatment for diarrhoea.

The American College of Medical Toxicology and the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology recommend that no one use homeopathy as a treatment for disease or as a preventative health measure. These organizations report that there is no evidence that homeopathic treatment is effective, but that there is evidence that using these treatments causes harm and may carry indirect health risks by delaying effective treatments.

Explanations of perceived effects

There are a variety of explanations why homeopathy seems to cure diseases or alleviate their symptoms even when the remedies themselves are inert:

- Placebo effect: the intensive consultation process and expectations in homeopathic preparations can cause this effect.

- Therapeutic effects of the consultation — the care, concern and comfort that the patient experiences when relying on a compassionate caregiver can have a positive effect on the well-being of the patient.

- Natural healing without assistance: the time and ability of the body to heal without intervention can eliminate many diseases spontaneously.

- Unidentified treatments: a diet, exercise, environmental agent or treatment may have occurred for a different disease.

- Regression to the average: because many diseases and conditions are cyclic, symptoms vary in time and patients tend to look for help when discomfort is maximum; then they may feel better anyway, but due to the simultaneity of the homeopata visit they attribute the improvement to the remedy taken.

- Non-homeopathic treatment: patients can also receive standard medical assistance at the same time as homeopathic treatment and be responsible for the first improvement.

- Eating unpleasant treatments: Homeopaths often recommend that their patients abandon medical treatments such as surgery or drugs, which may cause annoying side effects; improvement is attributed to homeopathy when the real cause is the cessation of treatment that caused the collateral effects in the first place, but the underlying disease remains untreated and is still a danger to the patient.

Effects on other biological systems

While some articles have suggested that high-dilution homeopathic solutions may have statistically significant effects on organic processes such as grain growth, histamine release by leukocytes, and enzymatic reactions, such evidence is disputed because the attempts to replicate them have failed.

In 1985, the French immunologist Jacques Benveniste sent an article to the journal Nature while he was working at INSERM. He claimed to have discovered that basophils, a type of white blood cell, released histamine when exposed to homeopathic dilutions of anti-immunoglobulin E antibodies. The journal's editors, skeptical of the results, requested that the study be replicated in a different laboratory. After reproducing it in four laboratories, the study was published. Still skeptical of the conclusions, Nature organized an independent research team to determine the accuracy of the research, consisting of Nature editor and physicist sir John Maddox, American scientific fraud investigator Walter Stewart and skeptic James Randi. After investigating the experiment's conclusions and methodology, the team found that the experiments were "statistically poorly controlled" and "interpretation had been clouded by the exclusion of measures in conflict with the claim." He concluded, “We believe that the experimental data have been uncritically evaluated and their imperfections inadequately reported.” James Randi doubted that there had been any deliberate fraud, but the researchers had allowed his “wishful thinking” to influence their interpretation of the data.

Ethics and safety

Providing homeopathic remedies has been described as unethical. Michael Baum, Emeritus Professor of Surgery and Visiting Professor of Medical Humanities at University College London (UCL), has described homeopathy as a "cruel deception".

Edzard Ernst, the UK's first Professor of Complementary Medicine and a former homeopath, has raised concerns about pharmacists violating their code of ethics by failing to provide their patients with the “ relevant and necessary information” about the true nature of the homeopathic products they promote and sell:

My call is simply to honesty. Let people buy whatever they want, but tell them the truth about what they're buying. These treatments are biologically unlikely and clinical trials have shown that they do absolutely nothing in humans. The argument that this information is not relevant or important to customers is quite and simply ridiculous.

Patients who choose to use homeopathy over evidence-based medicine risk missing out on timely diagnosis and effective treatment of serious diseases such as cancer.

Adverse reactions

Some homeopathic remedies use highly diluted poisons such as belladonna, arsenic, and poison ivy. The original ingredients are only in rare cases present at detectable levels. Adverse reactions may be due to improper preparation or intentional underdilution. Serious adverse effects such as epilepsy and death have been reported due to or associated with the use of some homeopathic remedies. Cases of arsenic poisoning have occurred following the use of homeopathic arsenic preparations. Zicam Cold remedy nasal gel Zicam cold), which contains 2X (1:100) zinc gluconate, would have caused a small percentage of its users to lose their sense of smell. 340 cases were settled out of court in 2006 for USD 12 million. In 2009, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, United States) recommended discontinuing three discontinued Zicam cold remedies because they could cause permanent damage to consumers' sense of smell. Zicam was released without a New Drug Application (NDA, New Drug Application) under a clause in the FDA Compliance Policy Manual called "Conditions under which homeopathic medicines may be placed on the market" (CPG 7132.15). However, the FDA warned Matrixx Initiatives, its manufacturer, through a Warning Notice that this policy did not apply when there was a health risk to consumers.

A 2000 review reported that homeopathic products are 'unlikely to cause serious adverse reactions'. In 2012, a systematic review of the evidence on the potential adverse effects of homeopathy concluded that "homeopathy has the potential to harm patients and consumers in both direct and indirect ways". alternative to an effective cure, even the most "innocuous" treatment can become life-threatening."

Lack of efficacy

The lack of convincing scientific evidence to support its efficacy and the use of remedies without any active ingredients have led to characterizations of pseudoscience and quackery, or, in the words of a 1998 medical review, "placebo therapy." at best and quackery at worst". England's Chief Medical Officer Dame Sally Davies has said that homeopathic remedies are "garbage" and serve no purpose other than placebo. Jack Killen, Acting Deputy Director of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, said homeopathy "goes beyond all current understanding of chemistry and physics." He added: "There is, to my knowledge, no disease for which homeopathy has been proven to be an effective treatment." Ben Goldacre said that homeopaths who misrepresent scientific evidence for a scientifically illiterate public have "excluded themselves from medicine." academic and all criticism has too often been met with evasion rather than debate." Homeopaths often prefer to ignore meta-analyses in favor of a misleading selection of positive results, such as promoting a particular observational study (one Goldacre describes as " a little more than a consumer satisfaction survey") as if this were much more informative than a series of randomized controlled trials.

Referring specifically to homeopathy, the UK House of Commons Science and Technology Committee stated:

In our view, systematic reviews and meta-analysis demonstrate conclusively that homeopathic products are not better than placebos. The Government shares our interpretation of the evidence.

In the Committee ' s view, homeopathy is a placebo treatment and the Government should have a policy on prescribing placebos. The Government is reluctant to address the provenance and ethics of prescribing placebos to patients, which usually depends on some degree of deception to the patient. The placebos prescription is not consistent with the choice of the informed patient, which the Government ensures is very important, since it means that patients do not have all the information necessary to make a meaningful decision. Beyond ethical problems and the integrity of the doctor-patient relationship, prescribing pure placebos is a bad medicine. Its effect is not reliable and unpredictable and cannot form the exclusive foundation of any treatment in the NHS [National Health System].

The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine of the National Institutes of Health (United States) stated:

Homeopathy is a controversial issue in the investigation of complementary medicine. Several of the key concepts of homeopathy are not consistent with the fundamental concepts of chemistry and physics. For example, it is not possible to explain in scientific terms how a remedy containing little or no active ingredient can have some effect. This, in turn, creates great challenges to rigorous clinical research of homeopathic remedies. For example, one cannot confirm that an extremely diluted remedy contains what is named on the label, or develop objective measurements that show effects of extremely diluted remedies on the human body.

Alternative to medical treatment

In the clinical setting, patients who choose to use homeopathy over scientific medicine risk missing out on early diagnosis and effective treatment, thus worsening the consequences of serious illnesses. Critics of homeopathy they cite cases of homeopathic patients who refused to receive correct treatment for diseases that could easily have been diagnosed and treated with evidence-based medicine and who have died as a consequence, in addition to the "marketing practice" of criticizing and downplaying homeopathic medicine. effectiveness of scientific medicine. Homeopaths claim that the use of conventional medicines will "push disease deeper" and cause more severe illness, a supposed process called "repression". Some homeopaths, especially non-physicians, advise against vaccination. Some suggest replacing it with "nosode", a homeopathic product created from biological material with including pus, infected tissue, sputum bacillus, or, in the case of "intestinal nosodes", feces. While Hahnemann opposed such preparations, contemporary homeopaths often use them even though there is no evidence to indicate any beneficial effect. Cases of homeopaths advising against the use of antimalarial drugs have been identified. This places travelers to the tropics who follow the recommendation in grave danger, as homeopathic remedies are completely ineffective against the malaria parasite.

In a 2004 case, a homeopath told one of his patients to stop taking conventional medication for a heart condition. On June 22 of that year he advised her: "Give up all medicines, including homeopathic ones." Two months later, around August 20, he insisted that he no longer needed to continue his medical treatment. On August 23, he added, "He just can't take any drugs. I have suggested some homeopathic remedies. [...] I feel sure that if you follow the recommendation you will recover your health. The patient was admitted to the hospital the next day, where she died eight days later. Her final diagnosis was "acute heart failure due to discontinuation of treatment."

In 1978, George Vithoulkas stated that if syphilis is treated with antibiotics, it would develop into secondary and tertiary syphilis with involvement of the central nervous system. Anthony Campbell, then a specialist physician at the Royal London Homeopathic Hospital, retorted "The unfortunate layman might well be misled by Vithoulkas's rhetoric into refusing to follow orthodox treatment." Vithoulkas's sayings spread the idea that treating a disease with medication it will only drive it deeper into the body. This is in conflict with scientific studies, which indicate that penicillin treatment produces a complete cure of syphilis in more than 90% of cases.

A 2006 review by W. Steven Pray of Southwestern Oklahoma State University's School of Pharmacy recommended that schools of pharmacology include a required course on medications and treatments without evidence, to promote discussion of ethical dilemmas inherent in recommending products no guarantee of safety and efficacy and that students should be taught where unproven systems such as homeopathy stray from evidence-based medicine. In an article titled "Should We Keep an Open Mind to Homeopathy? » Published in the American Journal of Medicine, Michael Baum and Edzard Ernst wrote that “Homeopathy is among the worst examples of faith-based medicine. [...] These axioms [of homeopathy] are not only out of step with the scientific facts, they are also directly opposed to them. If homeopathy is correct, much of the physics, chemistry, and pharmacology must be incorrect."

In 2013 sir Mark Walport, the UK Government's new Chief Scientific Adviser and head of the Government's Office for Science, said of homeopathy: "My scientific view is absolutely clear: homeopathy is nonsense, it is science. My advice to ministers is clear: there is no science in homeopathy. The most it can have is a placebo effect. It is then a political decision whether they spend money on it or not". The only [opinion being ignored] I could conceive of is homeopathy, which is crazy. It is not supported by scientific bases. In fact all of science points to the fact that it is not sensible at all. The clear evidence is saying that it is wrong, but homeopathy is still used in the NHS [National Health System]."

Regulation and prevalence

Homeopathy is quite common in some countries, while in others it is rare; it is highly regulated in some and virtually unregulated in others. It is practiced worldwide and professional qualifications and licenses are required in most countries. In some countries there are no specific legal regulations regarding the practice of homeopathy, while in others a scientific medical degree or a medical degree is required. licensed by accredited universities. In Germany, to become a homeopath, one must attend a three-year training program, while France, Austria, and Denmark require licenses to diagnose any disease or dispense any product intended to treat a disease.

Some homeopathic treatments are covered by public health services in several European countries, including France, the UK, Denmark and Luxembourg. In other countries, such as Belgium, homeopathy is not covered. In Austria, scientific proof of effectiveness is required by the public health service to reimburse medical treatment, and homeopathy is listed as non-reimbursable, but exceptions can be made; private health insurance policies sometimes include homeopathic treatment. The Swiss government, after a 5-year trial, withdrew coverage of homeopathy and four other complementary treatments in 2005, claiming they did not meet efficacy and cost-effectiveness criteria, but following a 2009 referendum the five therapies they have been reinstated for an additional 6-year probationary period beginning in 2012.

The Indian government recognizes homeopathy as one of its national systems of medicine; AYUSH or Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy has been established under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The Central Council of Homeopathy was established in 1973 to oversee higher education in homeopathy and the National Institute of Homeopathy in 1975. A minimum of an accredited diploma in homeopathy and registration with a state registry or the Central Register of Homeopathy are required. Homeopathy to practice homeopathy in India.

Public Opposition

In the United States, the president of the National Council Against Health Fraud said that "Homeopathy is a fraud perpetrated against the public with the blessings of the government, thanks to the abuse of political power of the Senator Royal Copeland [main promoter of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 1938]".

Spoofs of "overdosing" on homeopathic preparations by individuals or groups through "homeopathic suicide" have become popular ever since James Randi began swallowing entire bottles of homeopathic sleeping pills before giving his talks. In 2010 The UK's Merseyside Skeptics Society launched the 10:23 campaign, which encouraged mass overdoses in public. In 2011 this expanded and 69 groups participated, of which 54 uploaded recordings of the process. In April 2012, at the SkeptiCal conference in Berkeley, more than 100 people participated in a massive overdose of coffea cruda, homeopathic preparation supposed to relieve insomnia.

The non-profit and educational organizations Center for Inquiry (CFI) and the associated Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI) sued the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, United States), criticizing Boiron for misrepresenting the labeling and Oscillococcinum advertising. CFI in Canada appealed to consumers who felt harmed by homeopathic products to contact them.

In August 2011, a class action lawsuit was filed against Boiron on behalf of "all California residents who have purchased Oscillo on any day in the last 4 years". The charges were that it was "nothing more than a sugar pill", "despite falsely advertising that it contained an active ingredient known to treat flu symptoms".

Reporter Erica Johnson for CBC News' Marketplace program led an investigation into the Canadian homeopathic industry. Her conclusions were that it is "based on faulty science and really wacky thinking." Skeptics from the Center for Inquiry (CFI) participated in a mass overdose outside an emergency room in Vancouver, B.C., taking entire bottles of "medication" that should have made them drowsy, nauseated, or died. After 45 minutes of observation, no adverse effects were manifested. Johnson asked homeopaths and their corporate representatives for cancer cures and vaccination claims. All reported positive results, but none could offer scientific support for her claims, only that "it works." Johnson was unable to find any evidence that homeopathic preparations contained any active ingredients. Analyzes conducted at the University of Toronto's Department of Chemistry found that the active ingredient was so small that "it is equivalent to five billion times smaller than the amount of aspirin... in a single pill." Belladonna and ipecac "would be indistinguishable from each other in a blind assay".

Contenido relacionado

Pinocytosis

Cochrane Library

Human anatomy