History of the Dominican Republic

The history of the Dominican Republic dates back to the year 600 AD. C., when the occupants of the island were the Tainos. The island of Quisqueya was claimed by Spain in 1492, and was part of Spanish America.

Starting in the 17th century the French settled in the west of the island, creating what would later become Haiti. Spain handed over its part of the island of Santo Domingo to republican France when it was defeated in 1795, with which the entire island became a French colony. After Haiti's independence in 1804, the French held the rest of the island until 1809.

After a brief attempt at independence, the Dominicans fell under the control of Spain, which regained the eastern part of the island under the Treaty of Paris (1814). The people of Santo Domingo decided to rebel against Spain in November 1821 to join the South American country of Gran Colombia, rejected by Bolívar's debt with Haiti, being the same situation with the US, leaving the option of annexing the Republic to Spain. Haiti occupied the republic in 1822, and the republic fought for its independence until it was finally achieved in 1844.

Due to a strong economic recession, Haitian threats and the war of secession in the United States, Spain re-annexed the country in 1861, and it was not until 1865 that the Dominican Republic finally regained its independence. From the 1860s to the 1910s, the country experienced internal strife, leading to a United States invasion and occupation of the country from 1916 to 1924.

Circa 1930, the Dominican Republic found itself under the control of ruthless dictator Rafael Leónidas Trujillo, who ruled the country until 1961. Hundreds of Dominicans lost their lives, were imprisoned and tortured by Trujillo's henchmen. Many survivors remained mutilated for the rest of their lives; some had permanent scars on their bodies, and others suffered from mental illness. In 1937, he ordered the army to kill Haitians living in the border area. The army killed some 17,000 Haitians from the night of October 2, 1937 to October 8, 1937.

During this long period of oppression and death, the Trujillo government extended its policy of state terrorism beyond national borders. Notorious examples of Trujillo's reach abroad are the failed assassination attempt against Venezuelan President Rómulo Betancourt (1960), the kidnapping and subsequent disappearance in New York City of the Basque professor Jesús Galíndez (1956), the murder of the writer José Almoina and crimes committed against Cubans, Costa Ricans, Nicaraguans, Colombians, Puerto Ricans, and Americans. Trujillo became a strong ally of the United States in the years after World War II, opposing communism and leading attempts to overthrow Fidel Castro in the Escambray Rebellion.

Trujillo's support eroded as his cruel actions became internationally notorious, and he eventually lost the support of the United States and the Catholic Church. On May 30, 1961, his Chevrolet Bel Air was ambushed by military coup leaders and other citizens close to the regime. He was shot dead. Soon after, the coup plotters were rounded up and executed, and the Dominican Republic would descend into anarchy by mid-1965, necessitating a US occupation once more. This second US invasion was supposedly to prevent "another Cuba". The US subsequently ensured that a likable and trustworthy anti-communist dictator was re-established, this time in the form of former Trujillo protégé Joaquín Balaguer. Some 50,000 Haitians were sold by the Haitian government to work on Dominican plantations since the Trujillo era and during the Balaguer presidency.

Unemployment, government corruption, inconsistent electrical service, and massive illegal immigration from Haiti led the republic to suffer ongoing social and economic problems throughout the 21st century, with many Dominicans leaving for the United States and Spain primarily. There is currently a Constitutional and democratic government in the Dominican Republic, elected by the majority of the voters (2020-2024).

Pre-Columbian era

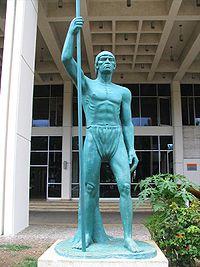

Successive waves of Arawak immigrants, moving north from the Orinoco delta in South America, settled in the Caribbean islands. Around the year 600, the Taíno Indians, an Arawak culture, arrived on the island, displacing the previous inhabitants. The last Arawak migrants, the Caribs, began moving to the Lesser Antilles in the 15th century, invading Taino villages on the eastern coast of the island at the same time as the Spanish arrived in 1492.

The Taínos called the island Quisqueya (mother of all lands) and Haiti (land of high mountains). At the time of Columbus's arrival in 1492, the island's territory consisted of five chiefdoms: Marién, Maguá, Maguana, Jaragua, and Higüey. These were governed respectively by the caciques Guacanagarix, Guarionex, Caonabo, Bohechío and Cayacoa.

Colonial period (1493-1821)

Arrival of the Spanish and colonization

Christopher Columbus landed on the island on his maiden voyage on December 5, 1492, giving it the name Hispaniola. Believing that the Europeans were somehow supernatural, the Tainos welcomed them with all honors. It was a totally different society from the one the Europeans came from. Guacanagarix, the host chief who welcomed Christopher Columbus and his men, treated them kindly and gave them everything they wanted. However, the egalitarian system of the Tainos faced the structures of the feudal system of the Europeans. This led the Europeans to believe that the Tainos were weak, and they began to treat the tribes more violently. Columbus tried to mitigate this when he and his men left Quisqueya , leaving the Tainos with a good first impression.

Columbus had established a firm alliance with Guacanagarix, who was a powerful chief on the island. After the shipwreck of the Santa María, Columbus decided to establish a small fortress with a garrison of men who could help him claim this possession. The fort was named La Navidad, because the events of the shipwreck and the founding of the fort occurred on Christmas Day. The garrison, despite all the island's wealth and beauty, was rocked by divisions that ended in conflict between these early Europeans. The most rapacious began to terrorize the members of the Taíno, Ciguayo and Macorix tribes to the point of trying to take their women.

Seen as weak by the Spanish and even by some of his own people, Guacanagarix tried to come to terms with the Spanish, who saw his peace as someone in submission. They treated him with contempt and even had some of his wives. The powerful cacique of Maguana, Caonabo, could not bear the insults and attacked the Europeans, destroying Fort La Navidad. Guacanagarix was appalled by this turn of events, but he did nothing to help, probably hoping the importunate foreigners would not return. However, they returned.

In 1493, Columbus returned to the island on his second voyage and founded the first Spanish colony in the New World, the city of La Isabela. In 1496, his brother Bartolomé Colón established the settlement of Santo Domingo de Guzmán on the south coast, which became the new capital. It is estimated that the 400,000 Taínos who lived on the island were enslaved before working in the gold mines. As a consequence of oppression, forced labor, hunger, disease, and mass murder,[citation needed] it is estimated that by 1508 that number had been reduced to about 50,000. In 1535, only 6,000 were alive.

During this period, the Spanish management changed hands several times. When Columbus set off on another exploration, Francisco de Bobadilla became governor. The accusations against Columbus by the colonists due to his mismanagement added to the tumultuous political situation. In 1502, Nicolás de Ovando replaced Bobadilla as governor, with an ambitious plan to expand Spanish influence in the region. It was he who had the most brutal treatment with most of the Tainos.

A rebel, Enriquillo, leading a group of those who had fled to the mountains, attacked the Spanish on several occasions over fourteen years. Finally, the Spanish offered him a peace treaty. In addition, they gave Enriquillo and his followers their own city in 1534. The city did not last long, for several years after its creation, a slave rebellion burned it down, killing everyone within it. same.

Taino extinction and African slavery

In 1501, Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella granted the first permission to Caribbean colonizers to import African slaves, who began arriving on the island in 1503. In 1510, the first major expedition, consisting of 250 ladino blacks, arrived in Hispaniola from Spain. Eight years later slaves of African origin arrived in the West Indies. The Spanish possession of the island was organized in 1511 as the Royal Audience of Santo Domingo. Sugar cane was introduced to Hispaniola from the Canary Islands, and the first sugar mill in the New World was established in 1516, on Hispaniola. The need for a labor force to meet the growing demand for cane cultivation of sugar led to an exponential increase in the importation of slaves in the following two decades. The owners of the sugar mills soon formed a new colonial elite, they convinced the King of Spain so that they could choose the members of the Royal Audience from among his ranks. The poorer settlers subsisted on hunting and the herds of wild cattle that roamed the entire island and selling their skins.

The first major slave revolt in the Americas occurred in Santo Domingo in 1522, when enslaved Muslims from the Wolof nation led an uprising on the sugar plantation of Admiral Don Diego Colón, son of Christopher Columbus. Many of these insurgents managed to escape to the mountains where they formed maroon communities.

While sugar cane greatly increased Spain's income on the island, large numbers of the newly imported slaves fled to the nearly impassable mountains in the island's interior, joining the growing communities of Maroons, literally, "wild". By the 1530s, Maroon bands had become so numerous that in rural areas, the Spanish could only travel safely off their plantations in large armed groups.

French corsairs

In the 1520s, the Caribbean Sea had been invaded by French privateers. In 1522 a ship from Santo Domingo bound for Seville was attacked by a French privateer named Jean Fleury, who appropriated all of his sugar cargo. In 1537, another French corsair attacked the towns of Azua and Ocoa, burning mills and houses and looting everything he could; while in 1540 a ship that had just set sail from the port of Santo Domingo was assaulted by English corsairs. In 1541 Spain authorized the construction of the walls of Santo Domingo, and decided to restrict sea travel to armed convoys. Another measure, which would destroy the sugar industry of Hispaniola, was that in 1561 Havana, more strategically located in relation to the Gulf Stream, was selected as the mandatory concentration point of the merchant fleets, which had a royal monopoly. on trade with the Americas. In 1564, the main cities in the interior of the island, Santiago de los Caballeros and Concepción de La Vega, were destroyed by an earthquake. In the 1560s the English also joined the French in the usual pirate raids on Spanish ships.

Colonial decline

With the conquest of the American continent, Hispaniola declined rapidly. Most of the Spanish settlers left the island for the silver mines of Bolivia as well as Mexico and Peru, while new Spanish immigrants omitted the island. Agriculture declined, imports of new slaves ceased, and white, free black, and slave settlers alike lived in poverty, weakening the racial hierarchy and intermingling aid, giving rise to a predominantly mixed Spanish, African, and Taino population.. Except for the city of Santo Domingo, which managed to maintain some legal exports, Dominican ports were forced to rely on the contraband trade, which, along with cattle, became the only source of livelihood for the island's inhabitants.. In 1586, Sir Francis Drake occupied the city of Santo Domingo, collecting a ransom for its return to Spanish rule.

In 1605, Spain, unhappy that Santo Domingo was facilitating trade between its other colonies and other European powers, ordered Governor Antonio de Osorio to attack the vast tracts of the colony's northern and western regions, forcing its inhabitants to resettle closer to the city of Santo Domingo. This action, known as the Devastations of Osorio, proved disastrous, with more than half of the relocated colonists dying of starvation or disease. English and French buccaneers took advantage of the retreat of Spain in a corner of Hispaniola to settle on Isla de la Tortuga in 1629. France established direct control in 1640, reorganizing it as an official colony and expanding the north coast of the island, although it would not be officially recognized by Spain until the signing of the Treaty of Aranjuez in 1777. In 1655, Oliver Cromwell dispatched a fleet, commanded by Admiral Sir William Penn, to conquer Santo Domingo. After meeting strong resistance commanded by the Count of Peñalva, Penn withdrew, taking the island of Jamaica instead. In 1666 a succession of epidemics of smallpox, measles, and dysentery wiped out the last Taínos and numerous Africans, leaving the country plunged into misery.

In the middle of the XVII century Santo Domingo was plunged into a serious economic and population crisis, since the rise of other American territories offered better guarantees. For this reason, between 1680 and 1691, 8 boats set sail for Santo Domingo, stopping there to leave Canarian families. There is evidence that they settled in Higüey and Bayaguana. In 1684, the new settlers arrived from the Canary Islands and settled in what would become San Carlos de Tenerife. These are 97 families, a total of 543 people, who would be dedicated to the supply of agricultural and livestock products for the city of Santo Domingo. In the year 1700, 39 more families arrived, after having suffered a serious smallpox epidemic in previous years that once again decimated the population. In 1709, 49 more families arrived who had to bribe the governor to be able to join the community of San Carlos.

The House of Bourbon replaced the House of Habsburg in Spain in 1700 and introduced economic reforms that little by little began to revive trade in Santo Domingo. The crown progressively relaxed the rigid controls and restrictions on trade between Spain and the other colonies. The last fleets sailed in 1737; the monopoly port system was abolished soon after. In the middle of the century, the population was reinforced by the colonization measures dictated by King Carlos III, which promoted the increase in the traditional emigration from the Canary Islands, the resettlement of the northern part of the colony and the plantation of tobacco in the Cibao Valley, and the importation of slaves was renewed. The population of Santo Domingo continued to decline at the beginning of the century, so that in the census carried out in 1737 it barely reached 6,000 inhabitants. Thereafter, a stage of improvement led to there being approximately 125,000 in 1790. Of this number, about 40,000 were white landowners, about 25,000 were free men of color or mulattoes, and about 60,000 were slaves.< sup>[citation needed] However, it remained poor and neglected, especially in contrast to the western part of the French neighbor Saint-Domingue, which became the largest colony rich in the New World and had four and a half times the number of inhabitants. As restrictions on colonial trade were eased, Saint-Domingue's colonial elites offered the main market to exporters of meat, hides, mahogany, and tobacco. from Santo Domingo. Another factor was the successes of local privateers during the wars with Britain.

Dominican privateers captured British, Dutch, French and Danish ships throughout the 18th century.

Treaty of Basel, cession to France and Haitian revolution

With the outbreak of the rebellion of the slaves against the French colonists in 1791, the rebels took advantage of the war between France and Spain and took refuge in the Spanish part, joining the Dominican militias, which were made up of natives of Santo Domingo, where the name “Dominican” comes from, because at that time Spanish troops never arrived in Santo Domingo to confront the French. Toussaint Louverture led the ex-slaves of France in the Spanish part, but then he was defeated by the French and betrayed the Dominicans. In 1795, France gained control of the entire island under the Treaty of Basel. In 1801 Louverture arrived in Santo Domingo to give free rein to his intentions to submit the entire island under his yoke, he even enshrined in his constitution that the island was one and indivisible. Shortly after, Napoleon sent an army that dominated the former slaves and ruled it for a few months, but yellow fever decimated Napoleon's troops, which was taken advantage of by the blacks who again rose up against these French in October of 1802 and finally defeated them in November 1803. On January 1, 1804 the victors declared Saint-Domingue as the independent republic of Haiti. Even after their defeat at the hands of the Haitians, a small French garrison remained in Santo Domingo.

At the end of February 1805, after having been crowned emperor, Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Jacobo I of Haiti) invaded, his troops advanced along two routes, one to the north (Dajabón-Santiago-La Vega-Santo Domingo), commanded by Henri Christophe, and the other to the south (Hincha-San Juan-Azua-Baní-Santo Domingo), commanded by Dessalines. In his advance along the southern route, the Haitian emperor found that the inhabitants of San Juan and Baní had evacuated their cities to protect themselves, for which reason he considered that the native population did not deserve his clemency. On March 6, when approaching the capital city, Dessalines ordered the burning of the town of San Carlos (located on the outskirts of the capital) and began the siege of the capital. On March 25, he ordered the total extermination of the population in his power, carrying out a massive transfer to the large Haitian cities to kill them in public squares by crushing (by horses and mules) and dismemberment. Three days later, three frigates and two French brigs arrived in Santo Domingo; Dessalines decided to withdraw his troops to Haiti. In April, Dessalines and Christophe, together with their troops, razed Santiago, Moca, Cotuí, La Vega, Azua, San Juan, Baní, among other cities, and massacred the inhabitants of these who had not fled to the Central Cordillera, annihilating some ten thousand people.[citation needed]

The French occupied the eastern part of the island, until they were defeated in the battle of Palo Hincado on November 7, 1808 by the native inhabitants of Santo Domingo, whose leader was the native of Cotuí Juan Sánchez Ramírez, who he was a wealthy landowner in his region, but he contributed all that wealth to defend the Dominican cause of preserving his nation that had both Spain and Africa, leaving both himself and his family in appalling economic ruin. The final capitulation of the French in the besieged city of Santo Domingo took place on July 9, 1809, with the help of the British Royal Navy.

Ephemeral Independence (1821-1822)

Spanish authorities showed little interest in their restored colony, and the period that followed is remembered as Silly Spain. Large ranching families like that of future landowner and Dominican President Pedro Santana became leaders in the southeast, the "law of the machete" ruled for a while. Former governor and lieutenant José Núñez de Cáceres declared the colony's independence as the state of Spanish Haiti on December 1, 1821, requesting admission to the Republic of Gran Colombia, but Haitian forces led by Jean-Pierre Boyer occupied the country nine weeks later.

On February 9, 1822, Boyer formally entered the capital, Santo Domingo, where he was received by Núñez de Cáceres who offered him the keys to the palace. Boyer refused the offer saying, "I have not come to this city as a conqueror but by the will of its inhabitants."

Haitian occupation (1822-1844)

The twenty-two-year Haitian occupation that followed is remembered by Dominicans as a period of brutal military rule, though the reality is more complex. There were large-scale land expropriations and failed efforts to force the production of export crops, impose military service, restrict the use of the Spanish language, and eliminate traditional customs such as cockfighting. Dominicans were reinforced in their perception of themselves as different from Haitians in "language, race, religion, and national customs." However, Boyer failed in his attempt to abolish slavery, as he It happened to Toussaint because both were unaware of the nature of the slave system that existed in Santo Domingo, since it was a patriarchal and domestic slavery. However, like Toussaint, Boyer established a kind of slavery against whites and mulattoes.

Haiti's constitution prohibited whites from owning land, and major landowning families were forcibly deprived of their property. Most emigrated to the Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico, or to independent Gran Colombia, usually with the support of Haitian officials, who acquired their land. Haitians, who associated the Catholic Church with the French masters who had exploited them before independence, confiscated all church property, deported all foreign clergy, and cut ties with the remaining clergy in the Vatican. The University of Santo Domingo, the oldest in the Western Hemisphere, lacking students, faculty and resources, closed. In order to receive diplomatic recognition from France, Haiti was forced to pay an indemnity of 150 million francs to the former French settlers, which was later reduced to 60 million francs, and because of this, Haiti imposed heavy taxes on the eastern part. of the island. Since Haiti was unable to supply adequate supplies for its army, the occupying forces largely survived by seizing or confiscating food and supplies at gunpoint.

Attempts to redistribute land conflicted with the communal land tenure system (terrenos comuneros), which had emerged with the ranching economy, and resentful new emancipated slaves are forced to grow cash crops under the Code Rural de Boyer. In rural areas, the Haitian administration was generally too inefficient to enforce its own laws. It was in the city of Santo Domingo that the effects of the occupation were felt most strongly, and it was there that the movement for independence originated.

First Republic (1844-1861)

In 1838, Juan Pablo Duarte founded a secret society called "La Trinitaria" to shake off the Haitian yoke that, together with his many collaborators, will be able to make the eastern part of the island independent. In 1843 they allied with a Haitian movement to overthrow Boyer. Due to his revolutionary thoughts and fight for Dominican independence, the new president of Haiti, Charles Rivière-Hérard, exiled and imprisoned the main Trinidadians. At the same time, Buenaventura Báez, an exporter of Azua mahogany and a deputy in the Haitian National Assembly, was negotiating with the French Consulate General for the establishment of a French protectorate. In a timely insurrection to get ahead of Báez, on February 27, 1844, the Trinitarians declared their independence from the Dominican Republic, with the support of Pedro Santana, a wealthy cattle rancher from El Seibo who commanded a private army of laborers who worked on his farms. lands and who fought for the revolutionary cause thus forming the Dominican independence army together with patriotic volunteers.

First Republic (1844-1861)

The first constitution of the Dominican Republic was approved on November 6, 1844. It included a presidential form of government with many liberal tendencies, but it was marred by article 210, imposed by Pedro Santana in the Constituent Assembly for the force, giving him the privileges of a dictatorship until the war of independence ended. These privileges not only helped him win the war, but also allowed him to persecute, execute, and drive into exile his political opponents, among whom were Juan Pablo Duarte.

During the first decade of independence, Haiti attempted several invasions to recapture the eastern part of the island: in 1844, 1845, 1849, and 1855. Although each was unsuccessful, Santana always used the threat of Haitian invasion as a justification for the consolidation of his dictatorial powers. For the Dominican elite—mostly landowners, merchants, and priests—the threat of reconquest by the more populous Haiti was enough to seek annexation by an outside power. Offering the deep waters of the Samaná Bay port as a lure, over the next two decades, negotiations were made with Britain, France, the United States, and Spain to declare a protectorate over the country. Without adequate roads, the regions of the Dominican Republic developed in isolation from one another.

In the south, the economy was dominated by cattle ranching (particularly in the southeastern savannah) and the cutting of mahogany and other hardwoods for export. This region retained a semi-feudal character, with little commercial agriculture, the hacienda as the dominant social unit, and the majority of the population living on a subsistence level. In the Cibao Valley—the richest agricultural fields in the nation—the peasants supplemented their subsistence crops with the cultivation of tobacco for export, mainly to Germany. Tobacco required less land than cattle ranching and was grown mainly by small farmers, who relied on street vendors to transport their crops to Puerto Plata and Montecristi.

Santana, enriching himself and his followers, resorted to multiple printings of inorganic money. In 1848, he was forced to resign, although he claimed ill health, and was succeeded by his vice president, Manuel Jimenes. After re-leading Dominican forces against a new Haitian invasion in 1849, Santana marched on Santo Domingo, deposing Jimenes. At his request, Congress elected Buenaventura Báez as president, but Báez was unwilling to serve as Santana's puppet, challenging his role as the country's recognized military leader. During his first term, offensive actions were taken against Haiti for the first time, immediately recapturing Isla Beata and Alto Velo.

On November 4, 1849, the Dominican Marine Infantry landed in Saltrou, and 50 cannon shots were fired in support of the forces that landed in the enemy zone, who annihilated several adversaries without suffering any casualties. The following day, disembarked in Anse-à-Pitre, where they set fire to its warehouses and military installations and whose defenders fled together with the population, full of fear, caused by the continuous bombardment of the cannons of the Dominican flotilla. Then they continued towards Los Cayos, meeting in the vicinity of the port with a Haitian vessel, which was pursued, hit and sunk, with three cannon discharges; then they bombarded the military installations and warehouses in the town of Los Cayos, without having to disembark their troops. Another of the ships encountered was the Charite, which tried to escape, but the brig 27 de Febrero, being lighter, caught up with it and upon boarding, they jumped on deck unleashing a bloody fight "hand-to-hand" on board, which resulted in 28 Haitians dead, 20 prisoners and wounded, as well as the confiscated ship. On January 2, 1850, the Dominican flotilla went to the Haitian coast for the second time; surprised the town of Dame-Marie with an intense bombardment, immediately destroying the Fort River that defended it, disembarking the Marine Infantry, which faced weak resistance from the military garrison stationed there, in which there were some deaths and several detainees. Then the Dominican sailors destroyed and burned the warehouses of merchandise and military installations that had survived the bombardment.

The success of these military operations helped to strengthen independence. Also during that period, mediation was initiated by France and Great Britain, in order to obtain a truce with Haiti, in their invasions. A small truce was achieved and at the beginning of 1851 a climate of peace was felt that had never been seen in the young republic.

In 1853, Santana was elected president for his second term, forcing Báez to seek exile. Three years later, after botching the Haitian invasion for the last time, he negotiated a lease agreement for a portion of the Samaná peninsula with an American company; popular opposition forced him to abdicate, allowing Báez to return and seize power. With the national treasury depleted, Báez printed eighteen million pesos for the purchase of the 1857 tobacco crop with this currency and exported it for cash for the benefit of himself and his followers. Cibaeños tobacco planters, who went bankrupt when inflation occurred, revolted, again turning to Santana, who was in exile, to lead the rebellion. After a year of civil war, Santana took Santo Domingo and installed himself as president. It should be noted that the period of the first republic was distinguished by the struggles and political instability in the nascent country.

Annexation to Spain and Restoration (1861-1865)

Annexation

Pedro Santana inherited a bankrupt government on the brink of collapse. Having failed in his initial offers to secure annexation to the US or France, Santana began negotiations with Queen Elizabeth II of Spain and the Captain General of Cuba to make the island a Spanish colony. The American Civil War rendered the United States incapable of enforcing the 'Monroe Doctrine'. In Spain, Prime Minister Leopoldo O'Donnell advocated renewing colonial expansion, supported the annexationist idea by carrying out a campaign in northern Morocco, which conquered the city of Tetouan. In March 1861, Santana officially annexed the Dominican Republic to Spain.

Restoration

This measure was widely opposed. A rebellion was put down, and then another invasion of Haiti, led by a rogue Dominican, was defeated and its leader executed. Santana was initially appointed Captain General of the new Spanish province, but it soon became apparent that the Spanish authorities planned to deprive him of his power, leading him to resign in 1862. On August 16, 1863, a national war of restoration in Santiago, where the rebels established a provisional government. The fighting spread everywhere and for the next two years it turned into an almost total social war. In most areas, the fighting involved blocking roads and access to rivers, preventing open spaces and even hand-to-hand combat. In the larger cities, the rebels devised trenches to face regiments of up to 5,000 men, led by leading Spanish and Dominican generals alike. At first, General Santana, who had been bestowed the title of Queen Elizabeth II, Marquis de Las Carreras, was in command of the Spanish forces opposing the rebels, but despite his great reputation, he proved incapable of stemming the tide.

Once the annexation took place, the illustrious General José María Cabral, a native of San Cristóbal, took a leading part in the restoration war. Cabral had been deported in August 1863 because his sympathy with the revolutionaries was suspected. He returned to the country in June 1864. Since the Spanish troops had deployed a considerable offensive in the South, one of the responses of the Restoration Government to that offensive was to name Cabral head of operations in the South, counting on his knowledge of the area. and his gift of command. From his first days in the leadership, Cabral began to reverse the inferiority in which the Dominicans found themselves in the South. He also managed to get Juan de Jesús Salcedo out of circulation and other warlords who were the protagonists of looting scenes. He also imposed Cabral order in the military formations.

Limited to large cities, the Spanish army was unable to defeat the guerrillas or contain the insurrection, and suffered heavy losses due to yellow fever. Spanish colonial authorities encouraged Queen Elizabeth II to leave the island, as they saw the occupation as a senseless waste of troops and money. However, the rebels were in a state of political disarray, and were unable to present a coherent set of demands. The first president of the provisional government, José Antonio Salcedo (allied with Báez) was deposed by General Gaspar Polanco, in September 1864, who, in turn, was deposed by General Antonio Pimentel three months later. The rebels formalized their provisional government by holding a national convention in February 1865, which promulgated a new constitution, but the new government exercised little authority over the guerrilla leaders of the various regions, who were largely independent of each other. others. Unable to extract concessions from the disorganized rebels, when the American Civil War ended in March 1865, Queen Elizabeth II annulled the annexation and independence was restored, with the last Spanish troops leaving before July.

The Spanish government eventually deployed a force of 51,000 men and their casualties amounted to 30,000.

Second Republic (1865-1916)

When the Spanish departed, most of the major cities were in ruins and the island was divided among several dozen caudillos. José María Cabral controlled most of Barahona and the southwest with the support of Báez's mahogany-exporting partners, while rancher Cesáreo Guillermo assembled a coalition of ex-generals "santanistas" in the southeast, and Gregorio Luperón controlled the north coast. Since the Spanish withdrawal in 1879, there have been 21 changes of government and at least 50 military uprisings.

In the course of these conflicts, two parties emerged. The "Red Party" (conservative) represented by cattle rancher from the mahogany-exporting south, Buenaventura Báez, who continued to seek annexation by a foreign power. The "Blue Party" (progressive), directed by Gregorio Luperón, representing the tobacco farmers and merchants of Cibao and Puerto Plata with a nationalist and liberal tendency in their orientation.

During these wars, the small and corrupt national army was outnumbered by militias organized and maintained by local caudillos who proclaimed themselves provincial governors. These militias were filled by landless farmers, peons, or plantation workers steeped in military service who usually engaged in banditry when there was no revolution.

About a month after the Nationalist victory, Cabral, whose troops were the first to enter Santo Domingo, overthrew Pimentel, but a few weeks later, General Guillermo led a rebellion in support of Báez, forcing Cabral to resign and allow Báez to retake the presidency in October. Báez was overthrown by the Cibao farmers under the Blue Party leader Luperón the following spring, but Luperón's allies turned on each other and Cabral reinstated himself as president in a coup. in 1867. After taking several "azulistas" to his cabinet the & # 34; red & # 34; they rebelled, returning Báez to power. In 1869, Báez negotiated an annexation treaty with the United States. With the support of United States Secretary of State William H. Seward, who hoped to establish a Navy in Samaná, in 1871 the treaty was annulled in the Senate of the United States through the efforts of abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner.

In 1874, the governor of Puerto Plata and member of the Red Party, Ignacio María González Santín, organized a coup in support of a rebellion by the Blue Party, but was deposed by the Blues two years later. In February 1876, Ulises Espaillat, backed by Luperón, was named president, but ten months later troops loyal to Báez returned him to power. After a year a new rebellion allowed González Santín to seize power, only to be deposed by Cesáreo Guillermo in September 1878, who in turn was overthrown by Luperón, in December 1879. Ruling the country from his hometown Puerto Plata, enjoying an economic boom due to tobacco exports to Germany, Luperón promulgated a new Constitution establishing a two-year presidential term limit through direct elections, suspended the semi-formal system of bribery, and began construction of the first railroad in the country, which connects the city of La Vega with the port of Sánchez in the bay of Samaná.

The Ten Years' War in Cuba brought Cuban sugar planters to the country in search of new land and safety from the insurrection that freed their slaves and destroyed their property. Most settled on the southeastern coastal plain, and, with the assistance of the Luperón government, built the nation's first mechanized sugar mills. They were later joined by Italians, Germans, Puerto Ricans, and Americans in forming the core of the Dominican sugar bourgeoisie, marrying and raising prominent families to consolidate their social standing. Disruptions in world production caused by the Ten Years' War, the American Civil War, and the Franco-Prussian War allowed the Dominican Republic to become a major exporter of sugar. Over the next two decades, sugar overtook tobacco as the main export product, while the old fishing hamlets of San Pedro de Macorís and La Romana were transformed into prosperous ports. To satisfy their need for better transportation, more than 300 kilometers of private railway lines were built by and to serve the sugar plantations in 1897. A fall in prices in 1884 led to a wage freeze, and subsequent shortages. of labor was filled by immigrant workers from the Leeward Islands, Virgin Islands, St. Kitts and Nevis, Anguilla, and Antigua (referred to by Dominicans as "cocolos"). These English-speaking blacks were often victims of racism, but many remained in the country, finding work as stevedores and building railroads and sugar refineries.

A large wave of Syrians, Lebanese and Palestinians left the Ottoman Empire from the late 19th century to the early 20th century and settled in the Dominican Republic. The first Arabs began to arrive in 1884. Dominicans complained that the Arabs lived a "worldly and miserable subsistence." The Arabs upon their arrival in the DR were referred to as 'smelly Turks with bad habits'.

Ulysses Heureaux's dictatorship and subsequent bankruptcy

Allying itself with emerging sugar interests, the dictatorship of General Ulises Heureaux, who was popularly known as "Lilís", brought unprecedented stability to the country through a government of a heavy hand that lasted almost two decades. Son of a Haitian father and a Saint Thomasan mother, Lilís distinguished himself as the second black president of the Dominican Republic, after Luperón. He served as president in the terms 1882-1883, 1887, and 1889-1899, exercising power through a series of puppet presidents when he was not in office. Incorporating the Reds and Blues into his government, he developed an extensive network of spies and informants to crush potential opposition. His government undertook a series of large infrastructure projects, including the electrification of Santo Domingo, the beginning of telephone and telegraph service, the construction of a bridge over the Ozama River, and the construction of a single-track railway linking Santiago and Puerto Plata, financed by the Amsterdam-based Westendorp Co..

The Lilís dictatorship was dependent on heavy borrowing from European and US banks to enrich itself, stabilize existing debt, strengthen the bribery system, pay for the military, finance infrastructure development and help establish sugar factories. However, sugar prices experienced a sharp decline in the last two decades of the 19th century. When the Westendorp Co. went bankrupt in 1893, he was forced to mortgage the nation's customs duties, the main source of government revenue, to a New York finance company called San Domingo Improvement Co. (SDIC), which took over its railway contract and the claims of its European bondholders in exchange for two loans, one for $1.2 million and one for £2 million. As public debt grew and it became impossible to maintain his political machine, Heureaux relied on secret loans from the SDIC, sugar planters, and local merchants. In 1897, with his government virtually bankrupt, Lilís prints five million inorganic pesos, known as "Las ballotetas de Lilís," ruining most Dominican merchants and inspiring a conspiracy. which ended in his murder. In 1899, when Lilís was assassinated by Cibao tobacco merchants who had been asking for a loan, the national debt was more than $35 million, fifteen times the annual budget.

The six years after the death of Lilís witnessed four revolutions and five different presidents. The Cibao politicians, who had conspired against Heureaux, Juan Isidro Jimenes, the richest planter of the country's tobacco, and General Horacio Vásquez, after being named president and vice president, quickly fell due to the division of the loot among his supporters into jimenistas and horacistas. Troops loyal to Vásquez overthrew Jimenes in 1903, but Vásquez was deposed by Jimenista general Alejandro Woss y Gil, who seized power for himself. The Jimenistas overthrew his government, but his leader, Carlos Morales Languasco, refused to return Jimenes to power, allying with the Horacistas, which led to a new revolt by his betrayed Jimenista allies.

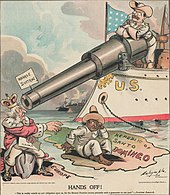

With the nation on the verge of rebellion, France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands sent warships to Santo Domingo to press the claim of their compatriots. In order to forestall military intervention, US President Theodore Roosevelt introduced the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, stating that the United States would assume responsibility for ensuring that the nations of Latin America complied with their obligations. financial obligations. In January 1905, by virtue of this corollary, the United States assumed the administration of the customs of the Dominican Republic. Under the terms of this agreement, a Receiver General, appointed by the US President, kept 55% of the total proceeds to pay foreign claimants, while remitting 45% to the Dominican government. After two years, the country's external debt was reduced from $40 million to $17 million. In 1907, this agreement became a treaty, transferring control of customs payments to the Bureau of Insular Affairs from the US and granting a $20 million loan from a New York bank as credit for pending claims, making the United States the sole foreign creditor of the Dominican Republic. In 1905, the Dominican peso was replaced by the US dollar.

In 1906, Morales Languasco resigned and the horacist and vice president Ramón Cáceres became president. After suppressing a rebellion in the northwest by General jimenista Desiderio Arias, his government brought political stability and economic growth, aided by new US investment in the sugar industry. However, his assassination in 1911, for which Morales Languasco and Arias were indirectly responsible, once again plunged the republic into chaos. For two months, executive power was in the hands of a civilian junta dominated by the head of the army, General Alfredo Victoria. The surplus of more than 4 million pesos left behind by Cáceres was quickly spent to suppress a series of insurrections.He forced congress to elect his uncle, Eladio Victoria, as president, but he was soon replaced by Archbishop Adolfo Alejandro Nouel. After four months, Nouel resigned, and was succeeded by Congressman José Bordas Valdez, who, allied with Arias and the Jimenistas, maintained power.

In 1913, Vásquez returned from exile in Puerto Rico to lead a new rebellion. During the revolution, United States Navy ships intervened to stop the bombardment of Puerto Plata by rebel factions. In June 1914, United States President Woodrow Wilson issued an ultimatum for the two sides to end hostilities. and agree to a new president, or the United States would impose one. After the provisional presidency of Ramón Báez, Jimenes was elected in October, and soon faced new demands, including the appointment of a US director of public works and financial adviser and the creation of a new military force commanded by officers of The US National Congress rejected these demands and began impeachment proceedings against Jimenes. The United States occupied Haiti in July 1915, with the implicit threat that the Dominican Republic might be next. Jimenes' Minister of War, Desiderio Arias organized a coup in April 1916, providing a pretext for the United States to occupy the Dominican Republic.

First US occupation (1916-1924)

The United States Marine Corps landed in Santo Domingo on May 15, 1916. Before their arrival, Jimenes resigned, refusing to be subdued by any foreigner. On June 1, the Marines occupied Montecristi and Puerto Plata. The first major confrontation occurred on June 27, 1916, in Las Trincheras, where in 1864 Dominican rebels had been able to stop a Spanish army. Two days after the Battle of Guayacanas, on July 3, 1916, the Marines moved into the Arias fortress in Santiago de los Caballeros. However, a military encounter was averted when Arias reached an agreement with William B. Caperton to cease resistance. The National Congress elected Dr. Francisco Henríquez y Carvajal as president, but in November, after he refused to comply with US demands, Wilson announced the imposition of a US military government, with Rear Admiral Harry Shepard Knapp as Military governor. The US military government implemented many of the institutional reforms carried out in the United States during the Progressive Era (Progressive Era), including the reorganization of the tax system, accounting and administration, the expansion of primary education, the creation of a national police force to unify the country, and the construction of a national highway system, including a highway that would link Santiago to Santo Domingo.

Despite the reforms, virtually all Dominicans resented the loss of their sovereignty to foreigners, some of whom spoke Spanish or showed genuine concern for the well-being of the nation, and the military government, unable to win the Backed by any of the prominent Dominican political leaders, he imposed strict laws and imprisoned critics of the occupation. In 1920, the US authorities enacted a Land Registration Law, which dismantled common lands and thousands of dispossessed peasants lacked formal titles to the lands they occupied, while legalizing false titles held by sugar companies. In the southeast, dispossessed peasants formed armed bands, called gavilleros, waging a guerrilla war that lasted for the duration of the occupation, with most fighting in Hato Mayor and El Seibo.

By 1921, the main guerrilla groups had been defeated, suffering a total of nearly 3,000 deaths. In the San Juan Valley, near the Haitian border, followers of a voodoo healer named Liborio resisted the occupation. and they helped the Haitian cacos in their war against the Americans, until their death in 1922. However, their Liborista movement lived on, maintaining a large commune in Palma Sola. However, the persecution of his followers continued and resulted in the Palma Sola massacre in 1962. Around 600 people died as a result of a napalm attack carried out by the Dominican government.

The main legacy of the occupation was the creation of a National Police Corps, used by the marines to help fight the different guerrillas, and later the main vehicle for promotion by Rafael Leonidas Trujillo.

In what is known as the "dance of the millions," with the destruction of European sugar beet crops during World War I, the price of sugar reached its highest level in history, from $5.50 in 1914 to $22.50 per pound in 1920. Dominican sugar exports increased from 122,642 tons in 1916 to 158,803 tons in 1920, earning a record $45.3 million. However, European production Sugar beet production recovered rapidly, which, along with the growth in world sugarcane production, saturated the world market, causing prices to plummet to just $2.00 by the end of 1921. This crisis led to many of local sugar planters out of business, allowing large US conglomerates to dominate the sugar industry. In 1926, only twenty-one major estates remained, occupying some 520,000 acres (2,100 km²). Of these, twelve US-owned companies owned more than 81% of the total acreage. While the foreign planters who had built the sugar industry integrated into Dominican society, these corporations expatriated their profits to the United States. As prices fell, the sugar plantations became increasingly dependent on Haitian workers. This was facilitated by the introduction of regulated labor contract by the military government, the growth of sugar production in the southwest near the border with Haiti, and a series of strikes carried out by cane-cutter cocolos. organized by the "Universal Negro Improvement Association".

In the 1920 United States presidential election, Republican candidate Warren Harding criticized the occupation and promised an eventual US withdrawal. While Jimenes and Vásquez demanded concessions from the United States, the collapse of the Sugar prices discredited the military government and gave rise to a new nationalist political organization, the Dominican National Union, led by Dr. Henríquez y Carvajal from exile in Santiago de Cuba, which demanded unconditional withdrawal. They formed alliances with frustrated nationalists in Puerto Rico and Cuba, as well as with critics of the occupation in the United States itself, most notably The Nation and the Haiti-San Domingo Independence Society. In May 1922, a Dominican lawyer, Francisco J. Peynado, went to Washington and negotiated what became known as the Hughes-Peynado Plan. It provided for the immediate establishment of a provisional government pending elections, the approval of all laws enacted by the US military government, and the continuation of the 1907 treaty until all foreign debts of the Dominican Republic had been paid. been settled. On October 1, Juan Bautista Vicini Burgos, the son of a wealthy Italian immigrant sugar planter, was named provisional president, and the US withdrawal process began.

Third Republic (1924-1965)

Government of Horacio Vásquez

The US occupation ended in 1924, with a democratically elected government led by Horacio Vásquez. In an effort to retain power from his followers, in 1927, Vásquez extended his term from four to six years. There was a contentious legal basis for the change, which was approved by Congress, but its effective enactment invalidated the 1924 constitution that Vásquez had sworn to uphold. The Great Depression reduced sugar prices to less than $1 per pound. The elections were scheduled for May 1930, but the way that Vásquez had extended his presidential term created suspicions about the impartiality of the elections. In February, a revolution was proclaimed in Santiago by a lawyer named Rafael Estrella Ureña. When the commander of the Dominican National Guard (the current National Police created under the occupation), Rafael Leónidas Trujillo, ordered his troops to remain in their barracks, the sick and aging Vásquez was forced to go into exile and proclaim Estrella provisional president. In May, Trujillo was elected with 95% of the vote, having used the military to harass and intimidate electoral staff and potential opponents of his. After his inauguration in August, at his request, the Dominican Congress proclaimed the beginning of the "Era of Trujillo."

The "Age of Trujillo" (1930-1961)

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo established absolute political control with severe repression of national human rights, while fostering economic development (from which he and his supporters mostly benefited). Trujillo used his political party, the Dominican Party, as a rubber stamp for his decisions. The true source of his power was the National Guard, the largest, best armed, and most centrally controlled institution of any military force in the nation's history. By disbanding the regional militias, eliminating the Marines (the main source of potential opposition), turning the National Guard into a virtual monopoly on power. The Trujillo regime was concerned with expanding the National Guard as one of the largest military forces. In Latin America, by 1940, Dominican military spending was 21% of the national budget. At the same time, it developed an elaborate system of spy agencies. In the late 1950s, there were at least seven categories of intelligence agencies, spying on each other, as well as on the people. All citizens were required to carry identification cards and secret police good conduct passes. Obsessed with adulation, Trujillo promoted a cult of his flamboyant personality. When a hurricane struck Santo Domingo in 1930, killing more than 3,000 people, Trujillo rebuilt the city, naming it "Ciudad Trujillo," and renaming it after the highest mountain in the country and the Caribbean, the Pico Duarte by "Pico Trujillo". More than 1,800 Trujillo statues were built, and all public works projects required a plaque with the inscription "Era de Trujillo, Benefactor de la Patria".

As sugar farms moved to Haiti to hire stationary migrant workers, increasing settlement in the Dominican Republic permanently, the 1920 census, conducted by the occupying US government, gave a total of 28,258 Haitians living in the country; by 1935 there were 52,657 Haitians.

In October 1937, Trujillo ordered the massacre of 14,000 to 40,000 Haitians, alleging that Haitian exiles in the Dominican Republic were conspiring to overthrow his regime (although he is credited with the law of an eye for an eye, trying to of claiming the massacres carried out by Haiti against the country in earlier times).[citation needed] This event later became known as "The Cut". The massacre was met with international criticism. The murder was the result of a new Trujillo policy called the "Dominicanization of the border." Place names along the border were changed from Creole and French to Spanish, the practice of voodoo was outlawed, quotas were imposed on the percentage of foreign workers companies could hire, and a law was passed preventing Haitian workers stay in the country after the sugar harvest. In 1938 thousands more Haitians were forcibly deported and hundreds were massacred.

Although Trujillo tried to emulate Generalissimo Francisco Franco, he welcomed Spanish Republican refugees after the Spanish Civil War. During the Holocaust in World War II, the Dominican Republic gave asylum to many Jews fleeing from Hitler who had been turned away by other countries. These decisions arose from a policy of whiteness, closely related to anti-Haitian xenophobia, which tried to add more whites to the Dominican population by encouraging immigration from Europe. As part of the Good Neighbor Policy, in 1940, the United States Department of State signed a treaty with Trujillo relinquishing control of the nation's customs. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Trujillo followed in the footsteps of the United States declaring war on the Axis Powers, even though he had openly professed his admiration for Hitler and Mussolini. During the Cold War, Trujillo maintained close ties to the United States, declaring himself the "anti-communist number one" of the world and becoming the first president of Latin America to sign a Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement with the United States.

Shortly after the end of World War II, Trujillo built a weapons factory in San Cristóbal. It manufactured hand grenades, gunpowder, dynamite, revolvers, automatic rifles, carbines, submachine guns, light machine guns, anti-tank guns, and ammunition. In addition, some quantities of mortars and aerial bombs were produced and the light artillery was rebuilt.

Trujillo and his family established a quasi-monopoly over the national economy. At the time of his death, he had amassed a fortune of around $800 million, he and his family owned 50-60 percent of the arable land, around 700,000 acres (2,800 km²), and Trujillo-owned businesses. 80% of commercial activity in the capital. He exploited nationalist sentiment to buy most of the nation's sugar plantations and refineries from US corporations; he operated a monopoly in the trade of salt, rice, milk, cement, tobacco, coffee, and insurance companies; he appropriated two large banks, several hotels, port facilities, the airline and a shipping line; he deducted 10% of the salaries of all public employees (supposedly for his party), and received a portion of the proceeds from prostitution. World War II brought increased demand for Dominican exports, and the 1940s and The early 1950s witnessed economic growth and a considerable expansion of the national infrastructure. During this period, the capital went from being just an administrative center for the national hub of shipping and industry, though it was pure "coincidence" that the new roads often carried Trujillo's plantations and factories, and the new ports benefited the export shipping of Trujillo companies.

Mismanagement and corruption led to major economic problems. In the late 1950s, the economy was deteriorating due to a combination of overspending on a festival to celebrate the regime's 25th anniversary, overspending on the purchase of sugar mills and private power plants, and a decision to make a large investment in state sugar production proved economically unsuccessful.

Throughout the 1950s the Dominican Republic had the most powerful air force in the Caribbean and possibly Latin America, second only to the United States, thanks to Trujillo's obsession with power. At their height, the hundreds of planes, initially flown by American and Brazilian mercenaries and maintained by Swedish mechanics, had the theoretical capacity to reach and bomb Havana in 3 hours and completely conquer Haiti in 24.

On June 19, 1949, a plane carrying Dominican rebels from Guatemala was intercepted and destroyed by the Dominican Coast Guard at Luperón on the north coast. Ten years later, on June 14, 1959, approximately two hundred exiles Dominicans and Cuban revolutionaries launched an invasion of the Dominican Republic from Cuba in hopes of overthrowing the Trujillo regime. The invaders were massacred just hours after landing.

Trujillo tried to intervene in the affairs of other Latin American nations, along with dictators Anastasio Somoza García (Nicaragua) and Marcos Pérez Jiménez (Venezuela). He supported Rafael Ángel Calderón Guardia's invasion of Costa Rica in 1955. Trujillo made tactical alliances with powerful US criminals, valuing the leverage they gave him to expand his campaigns against political enemies in the United States. In 1935, a gunman broke into a New York City apartment and killed Sergio Bencosme, the former Minister of the Interior of the Dominican Republic. In 1952, Andrés Requena, editor of an anti-Trujillo newspaper, was shot to death in another Manhattan apartment. In 1956, Trujillo's agents in New York killed Jesús Galíndez, a Basque exile who had worked for Trujillo but later denounced the Trujillo regime and brought it to the public eye in the United States.

In August 1960, the Organization of American States (OAS) imposed diplomatic sanctions against the Dominican Republic as a result of Trujillo's complicity in an attempt to assassinate Venezuelan President Rómulo Betancourt. Fearing that the country could unite against Trujillo and be replaced by the communists, the CIA helped a group of Dominican dissidents assassinate Trujillo in a car chase en route to his country home near San Cristóbal on the 30th. May 1961.

Sanctions remained in effect after Trujillo's assassination. His son Ramfis assumed de facto control, but was deposed by his two uncles, after a dispute over the possible liberalization of the regime. In November 1961, the military uprising of the "Rebellion of the Pilots" and the Trujillo family was forced into exile, fleeing to Spain, and the until then puppet president Joaquín Balaguer assumed final power.

Post-dictatorship instability (1962-1964) and second US occupation (1965)

At the insistence of the United States, Balaguer was forced to share power with a seven-member Council of State, established on January 1, 1962, and including moderate members of the opposition. The OAS sanctions were lifted on January 4, and, after an attempted coup, Balaguer resigned and went into exile on January 16. The reorganized Council of State, under the presidency of Rafael Filiberto Bonnelly headed the Dominican government until elections could be held. These elections, in December 1962, were won by Juan Bosch, a scholar and storyteller who had founded the opposition Partido Revolucionario Dominicano (PRD) in exile during the Trujillo years. His leftist policies, including land redistribution, nationalization of certain foreign holdings, and attempts to bring the military under civilian control, irritated military officials, the Catholic hierarchy, and the upper class, who feared "another Cuba". In September 1963, Bosch was overthrown by a right-wing military coup led by Colonel Elías Wessin y Wessin and was replaced by a three-man military junta. Bosch went into exile in Puerto Rico.

Later, a civilian triumvirate supposedly established a de facto dictatorship until April 16, 1965, when growing dissatisfaction spawned another military rebellion on April 24, 1965 demanding Bosch's restoration. The insurgents, civilian reformist officers and combatants loyal to Bosch under the command of Colonel Francisco Caamaño, who called themselves the constitutionalists, carried out a coup d'état, taking over the national palace. Immediately, the conservative military forces, led by Wessin y Wessin and who called themselves loyalists, responded with tank attacks and aerial bombardments against Santo Domingo.

General Wessin y Wessin began a tank advance on the capital on April 27, 1965. Loyalist forces regained control of segments of the capital (including the palace), but were repulsed in the Battle of Duarte Bridge and decimated by rebel attacks.

On April 28, 1965, anti-boschist army servicemen requested US military intervention and US forces landed, ostensibly to protect US citizens and evacuate other foreign nationals. In what was initially known as Operation Power Pack, 23,000 US soldiers were sent to the Dominican Republic.

Denying military victory, "constitutionalist" they quickly formed a constitutionalist Congress electing Caamaño president of the country. US officials opposed and supported General Antonio Imbert Barrera. On May 7, Imbert Barrera was sworn in as president of the so-called Government of National Reconstruction. The next step in the stabilization process, as planned by Washington and the OAS, was to arrange an agreement between President Caamaño and President Imbert Barrera to form a provisional government committed to early elections. However, Caamaño refused to meet with Imbert until several of the loyal officers, including Wessin and Wessin, were made to leave the country.

On May 13, General Imbert began "Operation Cleanup and his forces succeeded in eliminating pockets of rebel resistance outside Ciudad Nueva and censoring Radio Santo Domingo. Operation Cleanup ended on May 21.

On May 14, the Americans established a "corridor of security" that connected the San Isidro Air Base and the Duarte Bridge with the Embajador Hotel and the United States Embassy in downtown Santo Domingo, essentially cordoned off the constitutionalist zone of Santo Domingo. Roads were blocked and patrols ran continuously. Some 6,500 people from many nations were evacuated to safety. In addition, US forces were airdropping large relief supplies for Dominican nationals.

In mid-May, the majority of the OAS voted for "Operation Push Ahead," reducing US forces and replacing them with an Inter-American Peacekeeping Force (IAPF). The Inter-American Peace Force (IAPF) was formally constituted on May 23. The following troops were sent by each country: Brazil - 1,130, Honduras - 250, Paraguay - 184, Nicaragua - 160, Costa Rica - 21 military police, and El Salvador - 3 General Staff officers. The first contingent to arrive was a company of riflemen from Honduras who were soon backed by detachments from Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. Brazil fielded the largest unit, an armored infantry battalion. Brazilian General Hugo Alvim assumed command of the OAS ground forces, and on May 26 US forces began to withdraw.

On June 15, 1965, US M48A3 Patton tanks entered the city supported by loyalists without being stopped by rebel AMX-13 and Lanverk L-60 light tanks, falling their northern position even though the main stronghold resisted with the use of barricades and Molotov cocktails. Fighting continued on August 31, 1965, when a truce was declared. Most of the US troops left shortly thereafter and policing and peacekeeping operations were turned over to Brazilian troops, but a remnant of the US military remained until September 1966. 13 US soldiers were killed while 95 were injured. The Constitutionalists lost 77 combatants and 175 wounded.

Faced with ongoing threats and attacks, including a particularly violent attack at the Hotel Matum in Santiago de los Caballeros, Caamaño accepted a deal imposed by the US government. Dominican interim president Héctor García Godoy, sent Colonel Caamaño as military attaché to the Dominican Embassy in the United Kingdom.

Fourth Republic (1966 - present)

The twelve years of Balaguer (1966-1978)

In June 1966, Joaquín Balaguer, leader of the Reformist Party (which later became the Social Christian Reformist Party (PRSC), was elected and re-elected to office in May 1970 and May 1974, both times after the main opposition parties withdrew late in the campaign due to the high level of violence from pro-government groups.A new constitution was created, signed and put into use on November 28, 1966. The constitution stated that a president was to be elected to a four-year term.If there was a close election, there would be a second round of voting to decide the winner.The voting age was eighteen, but married persons under the age of eighteen could also vote. Balaguer led the Dominican Republic through a profound economic restructuring, based on opening the country to foreign investment, while protecting state-owned industries and certain private interests. Most of Balaguer's first nine years in the country's presidency experienced high growth rates (for example, an average GDP growth rate of 9.4 percent between 1970 and 1975), while people referred to this event like the "Dominican miracle". Foreign, especially US investment, as well as foreign aid, flowed into the country; Sugar, by then the country's main export product, enjoyed good prices on the international market and tourism grew enormously.

However, this excellent macroeconomic performance was not accompanied by an equitable distribution of wealth. While a group of new millionaires flourished during the Balaguer administrations, the poor simply became poorer. Furthermore, the poor were often targeted by state repression, and their socioeconomic claims were labeled as "communist" and treated accordingly by the state security apparatus.In the May 1978 elections, Balaguer was defeated in his candidacy for a fourth consecutive term by Antonio Guzmán of the PRD. Later, Balaguer ordered the troops to assault the Electoral Board and destroy the ballot boxes, declaring himself the winner. US President Jimmy Carter and the international community refused to recognize the alleged "victory" of Balaguer, and, faced with the denial of help from abroad, Balaguer had to admit defeat.

Governments of Antonio Guzmán (1978-1982), Salvador Jorge Blanco (1982-1986) and return of Balaguer to the presidency (1986-1996)

Antonio Guzmán inaugurated his government on August 16, marking the country's first peaceful transfer of power from one freely elected president to another. In the late 1970s, economic expansion, which had hitherto continued at its determined pace, began to slow considerably as sugar prices fell and oil prices rose. With inflation and unemployment rising, this triggered a wave of mass emigration from the Dominican Republic to the United States and Europe.

Elections were held again in 1982. Salvador Jorge Blanco of the Dominican Revolutionary Party defeated Bosch and the possible revival of Balaguer. Jorge Blanco undertook certain social and economic reforms; However, when international financial fiscal pressure was exerted on the country, the door was opened to a terrible economic and financial crisis that put the nation at an alarming point of inflation. During this period there was a series of social uprisings that put an end to the popularity of the PRD in the country and thus returning Balaguer to power representing the Reformist Party in 1986 where he remained in office for the next ten years. The 1990 elections were marked by violence and suspicion of voter fraud. The 1994 elections were also characterized by widespread violence during the campaign, often aimed at intimidating members of the opposition. Balaguer won in 1994, but most observers deduced that the elections had been rigged. Under pressure from the United States, Balaguer agreed to hold new elections in 1996. He himself would not go.

Pact for Democracy and rise of Leonel Fernández (1996-2000)

In 1996, Leonel Fernández Reyna of the Dominican Liberation Party (PLD) and a pupil of Juan Bosch obtained more than 51% of the vote, through an alliance with Balaguer. Fernández's first big execution was the sale of some state-owned companies. Although Fernández was praised for ending decades of isolation and improving relations with other Caribbean countries, he was criticized for neglecting public health, education, not fighting corruption and poverty that affected 60% of the population..

Bank bankruptcy and economic crisis, government of Hipólito Mejía (2000-2004)

In May 2000, Hipólito Mejía of the center-left PRD was elected president amid popular discontent over power outages and the recent privatization of the electricity sector. Since 1986 this party had not been a government. President Fernández, in his term, signed the Pan American Games and Hipólito Mejía carried out the 2003 Pan American Games in 2003, for which he had to build Olympic villages, and many sports facilities. Throughout the length and breadth of the country, in each community, a sports center was built, as a means for the youth and health of citizens. President Mejía encouraged agriculture and revived the countryside. In this period there was a bank fraud by the financial entity BANINTER, one of the main banks, which had problems since previous years, as well as BANCREDITO, and President Mejía returned part of their money to savers in order to avoid a crisis such as the "playpen" of Argentina, and to prevent all savers from withdrawing their money from all the banks and causing greater economic instability. His presidency saw higher inflation and peso instability. During his time as president, the relatively stable parity of the currency fell from 16 Dominican pesos to 1 US dollar to 60 pesos to 1 US dollar, leaving it at 42 pesos to 1 US dollar when he left power. the Dominican Republic participated in the US-led coalition in Iraq, as part of the "Hispano-American Brigade" led by Spain during the Iraq War. In December 2003 it was reported that at least three Iraqis, including two children, were injured as a result of an attack with five mortar shells against the base where the Dominicans were in Diwaniyah, without any of the Dominicans being affected. In 2004, the country withdrew its 604 troops from Iraq. In May 2004, Mejía was defeated by former President Leonel Fernández in the presidential elections.

Second and third terms of Fernández (2004-2008, 2008-2012) and rise of Danilo Medina, predominance of the PLD (2012 - 2020)

Fernández, elected in 2004, established austerity measures to deflate the peso and get the country out of its economic crisis, and in the first half of 2006, the economy grew 11.7%, bringing the peso down to 28 pesos for each dollar, although this improvement did not last long and the peso stabilized at 34 for each dollar. His administration was characterized by the construction of large works and institutional reforms, but also by the increase in citizen insecurity, cases of drug trafficking, administrative corruption and political clientelism.

In the last three decades, remittances from Dominicans residing abroad, mainly in the United States, have become increasingly important to the economy. From 1990 to 2000, the US Dominican population doubled in size, from 520,121 to 1,041,910, two-thirds of whom were born in the Dominican Republic. More than half of all Dominican-Americans live in New York, with the greatest concentration in the Washington Heights neighborhood of northern Manhattan. Over the last decade, the Dominican Republic has become the main source of immigration to New York, and today the New York metropolitan area has a larger Dominican population than any other city, with the exception of Santo Domingo itself. The communities Dominican plants have also developed in New Jersey (particularly Paterson), Miami, Boston, Philadelphia, Providence, and Lawrence, Massachusetts. Additionally, tens of thousands of Dominicans and their descendants live in Puerto Rico. Many Dominicans arrive in Puerto Rico illegally by sea through the Mona Channel, some to stay and others to cross into the US (see Dominican Immigration to Puerto Rico). Dominicans residing abroad sent an estimated 3 billion dollars in remittances to their relatives in the country in 2006. In 1997, a new law came into effect, allowing Dominicans residing abroad to withhold their citizenship and exercise the vote in the presidential elections. President Fernández, who grew up in New York, was the main beneficiary of this law.

Fernández was replaced by his own party mate Danilo Medina in the 2012 presidential election; Mejía, who was the main opponent for the PRD, was defeated by Medina in the first round.

Medina began his term with a series of controversial economic and social reforms in order to deal with the fiscal situation left behind by the Fernández administration, which despite an alleged austerity implemented by his government, left a large fiscal deficit during his last term amounting to more than 180,000 million Dominican pesos.

Contenido relacionado

21st century BC c.

Century XVIII

Angola