History of medicine

The history of medicine is the branch of history dedicated to the study of medical knowledge and practices over time. It is also a part of culture "it is actually the history of medical problems".

Since its ancient origins, human beings have tried to explain reality and the transcendental events that take place in it, such as life, death or illness. Medicine had its beginnings in prehistory, which also has its own field of study known as medical anthropology. Plants, minerals and parts of animals were used, most of the time these substances were used in magical rituals by shamans, priests, magicians, sorcerers, animists, spiritualists or fortune tellers. The first human civilizations and cultures based their medical practice on two apparently opposite pillars: a primitive and pragmatic empiricism (fundamentally applied to the use of herbs or remedies obtained from nature) and a magical-religious medicine, which turned to the gods to try to understand the inexplicable.

The Ancient Age data found shows medicine in different cultures such as Āyurveda medicine from India, ancient Egypt, ancient China and Greece. One of the first recognized historical figures is Hippocrates who is also known as the father of medicine; supposedly a descendant of Asclepius, through his family: the Asclepiades of Bithynia; and Galen. After the fall of Rome in Western Europe, the Greek medical tradition declined. In the V century a. C. Alcmeón de Crotona began a stage based on technique (tekhné), defined by the conviction that the disease originated from a series of natural phenomena that could be modified or reversed. This was the germ of modern medicine, although many other currents (mechanism, vitalism...) will emerge over the next two millennia and medical models from other cultures with a long medical tradition, such as China, will be incorporated.

In the second half of the 8th century, Muslims translated the works of Galen and Aristotle into Arabic, thus the Islamic doctors were induced in medical research. Some important Islamic figures were Avicenna, who along with Hippocrates has also been mentioned as the father of medicine, Abulcasis the father of surgery, Avenzoar the father of experimental surgery, Ibn al-Nafis the father of circulatory physiology, Averroes and Rhazes, father of pediatrics. Already by the late Middle Ages following the Black Death, important medical figures emerged from Europe such as William Harvey and Grabiele Fallopio.

In the past most medical thinking was due to what other authorities had previously said and was viewed in such a way that if it was said it stood as the truth. This way of thinking was mostly superseded between the XIV and XV, time of the Black Death pandemic. Likewise, during the XV and XVI, anatomy underwent a great advance thanks to the contribution of Leonardo Da Vinci, who projected together with Marcantonio della Torre, a medical anatomist from Pavia, one of the first and fundamental treatises on anatomy, called Il libro dell'Anatomia. Although most of the more than 200 illustrations of the human body that Da Vinci made for this treatise have disappeared, some of those that survive can be seen in his Treatise on Painting.

Starting in the 19th century saw large amounts of discoveries. Premodern biomedical research discredited various ancient methods such as that of the four humors of Greek origin, but it is in the XIX century, with Leeuwenhoek's advances with the microscope and Robert Koch's discoveries of bacterial transmissions, when it really saw the beginning of modern medicine. The discovery of antibiotics that was a great step for medicine. The first forms of antibiotics were sulfa drugs. Today antibiotics have become very sophisticated. Modern antibiotics can attack specific physiological locations, some even designed to be compatible with the body to reduce side effects. Dr. Edward Jenner discovered the principle of vaccination when he saw that milking cows that contracted the vaccinia virus by coming into contact with the pustules were immune to smallpox. Years later Louis Pasteur gave it the name of a vaccine in honor of Jenner's work with cows. At the end of the 19th century, French physicians Auguste Bérard and Adolphe-Marie Gubler summarized the role of medicine up to that time: "Heal rarely, alleviate often, comfort always."

Medicine of the XX century, driven by scientific and technical development, gradually consolidated as a more decisive discipline, although without ceasing to be the synergistic fruit of the medical practices experienced up to that moment. Evidence-based medicine is based on a fundamentally biologicist paradigm, but admits and proposes a health-disease model determined by biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors. Herbalism gave rise to pharmacology: from the various drugs derived from plants such as atropine, warfarin, aspirin, digoxin, taxol etc.; the first was arsphenamine discovered by Paul Ehrlich in 1908 after observing that bacteria died while human cells did not.

In the XXI century, knowledge about the human genome has begun to have a great influence, which is why Various gene-linked conditions have been identified for which cell biology and genetics are focused for management in medical practice, yet these methods are still in their infancy.

Origins of medicine

To talk about the origins of medicine, it is necessary to do so before the traces left by disease in the oldest known human remains and, to the extent that this is possible, before the traces that medical activity may have leave on them.

Marc Armand Ruffer (1859-1917), British physician and archaeologist, defined paleopathology as the science of diseases that can be demonstrated in ancient human remains.

The pathologies diagnosed in remains of human beings dating from the Neolithic include congenital anomalies such as achondroplasia, endocrine diseases (gigantism, dwarfism, acromegaly, gout), degenerative diseases (arthritis, spondylosis) and even some tumors (osteosarcomas), mainly identified on skeletal remains. Among the archaeological remains of the first Homo sapiens it is rare to find individuals over fifty years of age, so there is little evidence of degenerative or age-related diseases. On the other hand, there are many findings related to diseases or traumatic processes, the result of a life in the open air and in a little domesticated environment.

One of the most widely accepted hypotheses about the emergence of Mycobacterium (the germ that causes this disease) proposes that the common ancestor called Marchaicum, "free bacteria& #34;, would have given rise to modern Mycobacterium, including M. tuberculosis. The mutation would have occurred during the Neolithic, in connection with the domestication of wild bovids in Africa. The first evidence of tuberculosis in humans has been found in Neolithic bone remains, in a cemetery near Heidelberg, supposedly belonging to a young adult, and dated to around 5,000 years before our era. tuberculosis in Egyptian mummies dated between 3000 and 2400 BC. C.

Regarding the first medical treatments of which there is evidence, mention should be made of the practice of trepanation (perforation of the bones of the head to access the brain). There are archaeological finds of skulls with obvious signs of trepanation dating from the Neolithic period, between 4,000 and 2,400 years ago, for reasons that are supposed to be diverse. Trepanned bone remains with an excellent level of conservation, obtained by archaeological excavations carried out in Ensisheim (Alsace), allow us to assume that cranial surgeries were already practiced more than 7,000 years ago. There is also other evidence of ancient cranial surgeries obtained from excavations in the Danube basin, Denmark, Poland, France, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Spain or Peru.

Ethnology, on the other hand, extrapolates the discoveries made in pre-industrial cultures and civilizations that have managed to survive to the present day to understand or deduce the cultural and behavioral patterns of the first human societies.

In Neolithic sedentary societies, there was a character who had the function of a spiritual leader, that is, he healed the hunting wounded supported by divine influence and helped the community to manipulate the soul for hunting. These healers usually occupy a privileged social position and in many cases subspecialize to treat different diseases, as was evident among the Mexica, among whom could be found the shaman doctor (ticitl) more versed in magical procedures, the teomiquetzan, an expert especially in wounds and traumas produced in combat, or the tlamatlquiticitl, a midwife in charge of monitoring pregnancies. On the contrary, nomadic societies, gatherers and hunters, do not have the specialized figure of the healer and any member of the group can perform this function, mainly empirically. They used to consider the patient as "impure", especially in the face of incomprehensible pathological processes, resorting to divine explanation, as their cause.

The sick person is sick because they have transgressed some taboo that has irritated some deity, thus suffering the corresponding "punishment", in the form of illness.

The evolution of medicine in these archaic societies finds its maximum expression in the first human civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, pre-Columbian America, India and China. They expressed that double aspect, empirical and magical, characteristic of primitive medicine.

Mesopotamia

The "land between rivers" was home to some of the earliest and most important human civilizations (Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian and Babylonian) since the Neolithic.

Around 4000 B.C. C. the first Sumerian cities were established in this territory and for more than three thousand years these four cultures flourished, characterized by the use of a written language (cuneiform) that has been preserved to this day in numerous tablets and engravings.

It is precisely this capacity to transmit scientific, social, and administrative information through an enduring system that determined the cultural development of the first Sumerian settlements, and what allowed later historians to reconstruct their legacy.

The main testimony of the way of life of the Mesopotamian civilizations is found in the Code of Hammurabi, a compilation of laws and administrative regulations collected by the Babylonian king Hammurabi, carved in a block of diorite about 2.50 m in diameter. height by 1.90 m base and placed in the temple of Sippar. It determines throughout thirteen articles, the responsibilities incurred by doctors in the exercise of their profession, as well as the punishments provided in case of malpractice.

Thanks to this text and a set of some 30,000 tablets compiled by Ashurbanipal (669-626 BC), coming from the library discovered in Nineveh by Henry Layarde in 1841, it has been possible to intuit the conception of health and disease in this period, as well as the medical techniques used by its healing professionals.

Of all these tablets, some 800 are specifically dedicated to medicine, and among them is the description of the first known recipe. The most striking thing is the intricate social organization around taboos and religious and moral obligations, which determined the fate of the individual. A supernatural conception of the disease prevailed: this was a divine punishment imposed by different demons after the breaking of some taboo.

So the first thing the doctor had to do was identify which of the 6,000 or so possible demons was causing the problem.

To do this, they used divination techniques based on the study of the flight of birds, the position of the stars or the liver of some animals. The disease was called shêrtu. But this Assyrian word also meant sin, moral impurity, divine wrath, and punishment.

Any god could cause disease through direct intervention, the abandonment of man to his fate, or through incantations performed by sorcerers.

During healing all these gods could be invoked and required through prayers and sacrifices to remove their harmful influence and allow the sick man to heal. Among the entire pantheon of gods, Ninazu was known as "the lord of medicine" because of his special relationship with health.

The diagnosis then included a series of ritual questions to determine the origin of the disease:

Did you enmity the father against the son? Or the son against the father? Have you lied? Have you cheated on the balance weight?

And the treatments did not escape this cultural pattern: exorcisms, prayers and offerings are frequent healing rituals that seek to ingratiate the patient with the divinity or free him from the demon that stalks him.

However, it is also noteworthy an important herbal arsenal collected in several tablets: some two hundred and fifty healing plants are collected in them, as well as the use of some minerals and various substances of animal origin.

The generic name for the doctor was asû, but some variants can be found such as bârû, or diviner in charge of ritual interrogation; the âshipu, specialized in exorcisms; or the gallubu, a lower caste surgeon-barber who anticipates the figure of the European medieval barber, and who finds a counterpart in other cultures (such as the Aztec Tepatl). This cutter was in charge of simple surgical operations (extraction of teeth, drainage of abscesses, phlebotomy...).

In the Louvre Museum you can see a Babylonian alabaster seal of more than four thousand years old with a legend that mentions the first known name of a doctor: Oh, Edinmungi, servant of the god Girra, protector of women in labor, Ur-Lugal-edin-na, the doctor, is your servant! This seal, used to sign documents and prescriptions, represents two knives surrounded by medicinal plants.

The Persian invasion of 539 B.C. C. marked the end of the Babylonian empire, but you have to go back again some three thousand years to mention the other great civilization of the ancient Near East possessing a written language and a remarkably advanced medical culture: the Egyptian.

Ancient Egypt

During the long three thousand year history of Ancient Egypt, a long, varied and fruitful medical tradition developed.

Herodotus came to call the Egyptians the people of the most sans, due to the notable public health system they possessed, and the existence of "a doctor for each disease" (first reference to specialization in medical fields.

In Homer's Odyssey Egypt is said to be a country "whose fertile land produces many drugs" and where "every man is a physician". magical conception of the disease, but began to develop a practical interest in fields such as anatomy, public health or clinical diagnosis that represent a significant advance in the way of understanding how to get sick.

The climate of Egypt has favored the preservation of numerous papyri with medical references written in hieroglyphic script (from the Greek hierós: 'sacred', and glypho: 'to record') or hieratic:

- Ramesseum's papyrus (1900 a.C.), which describes magical recipes and formulas.

- Lahun's papyrus (1850 BC), which treat subjects as disparate as obstetrics, veterinary or arithmetic.

- The Papire Ebers (1550 BC), one of the most important and longest written documents found in ancient Egypt: it measures more than twenty meters in length and about thirty centimeters high and contains 877 sections that describe numerous diseases in various fields of medicine such as: ophthalmology, gynaecology, gastroenterology... and its corresponding prescriptions.

This papyrus contains the first written reference to tumors.

- The papier Edwin Smith (1650 BC), of mainly surgical content.

The medical information contained in the Edwin Smith papyrus includes the examination, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of numerous pathologies, with special dedication to various surgical techniques and anatomical descriptions, obtained in the course of the embalming and mummification processes of the corpses.

In this papyrus, three degrees of prognosis are established for the first time, similar to that of modern medicine: favourable, doubtful and unfavorable >.

- Daddy Hearst (1550 BC), which contains medical, surgical descriptions and some magisterial formulas.

- The papyrus of London (1350 BC), where magical recipes and rituals are mixed.

- The papyrus of Berlin (the Book of the heart) (1300 B.C.) that detail quite accurately some cardiac pathologies.

- The Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus (1300 BC).

- The Carlsberg papyrus (1200 BC) of obstetric and ophthalmological themes.

Among the numerous anatomical descriptions offered by Egyptian texts, it is worth highlighting those related to the heart and the circulatory system, collected in the treatise "The doctor's secret: knowledge of the heart", incorporated into the Edwin Smith papyrus:

The heart is a mass of flesh, origin of life and center of the vascular system (...) Through the pulse the heart speaks through the vessels to all members of the body.

The first references belong to the early monarchical period (2700 BC). According to Manetho, an Egyptian priest and historian, Atotis or Aha, pharaoh of the first dynasty, practiced the art of medicine, writing treatises on the technique of opening bodies.

The writings of Imhotep, vizier of Pharaoh Necherjet Dyeser, priest, astronomer, doctor and the first known architect, also date from that time. Such was his fame as a healer that he ended up deified, considering himself the Egyptian god of medicine.

Other notorious doctors of the Old Kingdom (from 2500 to 2100 BC) were Sachmet (physician to Pharaoh Sahura) or Nesmenau, director of one of the houses of life, temples dedicated to the spiritual protection of the pharaoh, but also proto-hospitals where medical students were taught while the sick were cared for.

Several gods watch over the practice of medicine: Thoth, god of wisdom, Sejmet, goddess of mercy and health, Duau and Horus, protectors of eye medicine specialists, Tueris, Heget and Neit, protectors of pregnant women at the time of childbirth, or Imhotep himself after being deified.

The Ebers papyrus describes three types of physicians in Egyptian society: the priests of Sekhmet, mediators with divinity and connoisseurs of a wide assortment of drugs, the civil (sun-nu) physicians, and magicians, capable of magical healing.

A class of helpers, called ut, who are not considered healers, assisted the medical caste in large numbers, outpacing the nursing corps.

There is evidence of medical institutions in ancient Egypt from at least the first dynasty.

In these institutions, already in the nineteenth dynasty, their employees had certain advantages (medical insurance, pensions and sick leave), and their working hours were eight hours.

The first known female physician, Peseshet, was also Egyptian, practicing during the fourth dynasty; In addition to her supervisory role, Peseshet evaluated midwives at a medical school in Sais.

Hebrew Medicine

Most of the knowledge of Hebrew medicine during the I millennium BCE. C. comes from the Old Testament of the Bible. It cites various laws and rituals related to health, such as isolating infected people (Leviticus 13:45-46), washing after handling deceased bodies (Numbers 19:11-19) and the burial of excrement away from dwellings (Deuteronomy 23:12-13).

The mandates include prophylaxis and suppression of epidemics, suppression of venereal diseases and prostitution, skin care, bathing, food, housing and clothing, regulation of work, sexuality, discipline, etc.

Many of these mandates have a more or less rational basis, such as circumcision, the supposed impurity of women in labor, impurity of women during menstruation, laws regarding food (prohibition of blood and pork), the Sabbath rest, the isolation of gonorrhea and leprosy patients, and home hygiene.

Hebrew monotheism made medicine theurgic: Yahweh was responsible for both health and disease. Monotheism in general means an advance: it facilitated the development of science by concentrating man on a single idea. He ended up with the notion of a god for every phenomenon of nature and every circumstance of life as postulated by polytheism. This allowed the study and investigation of the origin of each thing. [citation required]

Sickness can also be a divine test as in the case of Job: «Then Satan went out from the presence of Jehovah, and smote Job with a vicious scab from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head» (Job 2:7). The Hebrews adopted medical precepts from the peoples with whom they had contact: Mesopotamia, Egypt and Greece. The Talmud speaks of the total number of man's bones. The Hebrews noted that the man was missing the staff (the inner bone of the penis) typical of all male animals. The physician was called rophe, and the circumciser was uman.

Indian

Around 2000 B.C. C. in the city of Mohenjo-Daro (in present-day Pakistan), all the houses had a bathroom and many of them also had latrines. This city is considered the most advanced of Antiquity as far as hygiene is concerned. This culture of the Indus Valley (Pakistan) disappeared without leaving a legacy in the later cultures of India.

The Vedic period (between the 16th century and the VII BC) was an era of migrations and wars, which left behind texts such as the Rig-veda (the oldest text in India, from the mid II millennium BC), but demonstrates the complete absence of medical knowledge.

In the Brahminical period (6th century BCE BCE to X AD) the foundations of a medical system were formulated. Illnesses were understood by Hindus as karma, a punishment from the gods for a person's activities. But, despite its magical-religious component, Ayurvedic Hindu medicine made some contributions to medicine in general, such as the discovery that the urine of diabetic patients is sweeter than that of patients who do not suffer from this condition. pathology.

In order to diagnose a disease, Ayurveda doctors performed a thorough examination of patients, which included palpation and auscultation. Once the diagnosis was issued, the doctor gave a series of dietary instructions.

The two most famous texts of traditional Indian medicine (aiurveda) are the Charaka-samjita ( century). II BC) and the Susruta-samjita (III century AD).. C.).

The first school, Charaka, is based on mythology, as it says that a divinity came down to earth and upon encountering so many diseases, left a writing on how to prevent and treat them. Later this school would be based on the belief that neither health nor disease are part of what people should live and that life can be extended with effort. This school is similar to modern medicine in the area of treating chronic diseases. One of the greatest efforts of this school was to maintain the health of the body and mind, since, according to their beliefs, they were in constant communication.

According to Cháraka, neither health nor illness are predetermined (which contradicted the prevailing doctrine of karma in Hinduism at the time), and life can be prolonged with some effort.

The second school, Sushruta, based its knowledge on specialties, techniques formed to cure, improve and extend people's lives.

Chinese

Traditional Chinese medicine emerges as a fundamentally Taoist way of understanding medicine and the human body.

The Tao is the origin of the universe, which is sustained in an unstable balance as a result of two primordial forces: yin (earth, cold, feminine) and yang (sky, heat, masculine), capable of modifying the five elements of which the universe is made: water, earth, fire, wood and metal.

This cosmological conception determines a disease model based on breaking the balance, and its treatment in a recovery of that fundamental balance.

One of the first vestiges of this medicine is the Nei jing, which is a compendium of medical writings dated around the year 2600 B.C. C. and that will represent one of the pillars of traditional Chinese medicine in the following four millennia.

One of the earliest and most important revisions is attributed to the Yellow Emperor, Huang Di. In this compendium there are some interesting medical concepts for the time, especially of a surgical nature, although the reluctance to study human corpses seems to have reduced the effectiveness of his methods.

Chinese medicine developed a discipline halfway between medicine and surgery called acupuncture: According to this discipline, the application of needles on any of the 365 insertion points (or up to 600 according to the schools) would restore the lost balance between the yin and the yang.

Several medical historians have questioned why Chinese medicine remained anchored in this cosmological vision without reaching the level of technical science despite its long tradition and extensive body of knowledge, compared to the Greco-Roman model classic.

The reason, according to these authors, would be found in the development of the concept of logos by Greek culture, as a natural explanation detached from any cosmological model (mythos).

With the advent of the Han dynasty (AD 220-206), and with the heyday of Taoism (II to VII AD), emphasis begins on plant remedies and minerals, poisons, dietetics, as well as respiratory techniques and physical exercise.

From this dynasty, and up to the Sui dynasty (VI century) the following sages stood out:

- Chun Yuyi: It follows from their observations that they already knew how to diagnose and treat diseases such as cirrhosis, hernias and hemoptisis.

- Zhang Zhongjing: It was probably the first to differentiate the symptoms of therapeutics.

- Hua Tuo: A great multidisciplinary surgeon who is attributed the techniques of narcosis (Ma Jue Fa) and abdominal openings (Kai Fu Shu), as well as suture. It also focused on obstetrics, hydrotherapy and gymnastics exercises (Wu Qin Xi).

- Huang Fumi: Author of Zhen Jiu Yi JingA classic on acupuncture.

- Wang Shu He: Author of Mai JingA classic on the pulse shot.

- Ge Hong: alchemist, taoist and phytotherapist who developed longevity methods based on respiratory, dietary and pharmacological exercises.

- Tao Hongjing: expert in pharmacological remedies.

During the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasties, traditional Chinese medicine experienced great moments.

In the year 624 the Great Medical Service was created, from where medical studies and research were organized.

From this time we have received very precise descriptions of a multitude of diseases, both infectious and deficiency, both acute and chronic.

And certain references suggest great development in specialties such as surgery, orthopedics or dentistry.

The most notable physician of this period was Sun Simiao (581-682).

During the Song dynasty (960-1270) multidisciplinary scholars such as Chen Kua, pediatricians such as Qian Yi, specialists in legal medicine such as Song Ci, or acupuncturists such as Wang Wei Yi appeared.

Shortly after, before the arrival of the Ming dynasty, it is worth mentioning Hu Zheng Qi Huei (dietetician), and Hua Shuou (or Bowen, author of a relevant revision of the classic Nan Jing).

During the Ming (1368-1644) influences from other latitudes increased, Chinese doctors explored new territories, and Western doctors brought their knowledge to China.

One of the great medical works of the time was Li Shizhen's Great Treatise on Materia Medica.

Also include acupuncturist Yang Jizou.

From the XVII-XVIII century, reciprocal influences with the West and its technical advances, and with different philosophies prevailing (for example communism), have just shaped the current Chinese medicine.

Pre-Columbian America

During the entire historical period prior to its discovery by Europe, the vast territory of the American continent welcomed all kinds of societies, cultures and civilizations, which is why you can find examples of the most primitive Neolithic medicine, shamanism, and a almost technical medicine reached by the Mayans, the Incas and the Aztecs during their times of maximum splendor.

There are, however, some similarities, such as a magical-theurgical conception of illness as divine punishment, and the existence of individuals especially linked to the gods, capable of exercising the functions of healers.

Among the Incas there were doctors of the Inca (hampi camayoc) and doctors of the people (ccamasmas), with certain surgical skills resulting from the exercise of ritual sacrifices, as well as with vast herbal knowledge.

Among the most used medicinal plants were coca (Erytroxilon coca), yagé (Banisteriopsis caapi), yopo (Piptadenia peregrina), perica (Virola colophila), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), yoco (Paulinia yoco) or curare and some daturas as anesthetic agents.

The Mayan doctor (ah-men) was actually a specialized priest who inherited the position through family lineage, although it is also worth noting the pharmacological development, reflected in the more than four hundred recipes compiled by R. L. Roys.

The Aztec civilization developed an extensive and complex body of medical knowledge, news of which remains in two codices: the Códice Sahagún and the Códice Badiano.

The latter, by Juan Badiano, compiles a good part of the techniques known by the indigenous Martín de la Cruz (1552), which includes a curious list of symptoms presented by individuals who are about to die.

It is worth noting the discovery of the first medical school in Monte Albán, near Oaxaca, dated around the year 250 of our era, where some anatomical engravings have been found, among which it seems to be a cesarean section, as well as the description of different minor interventions, such as the extraction of dental pieces, the reduction of fractures or the drainage of abscesses.

Among the Aztecs, a difference was established between the empirical physician (again the equivalent of the late medieval European «barber») or tepatl and the shaman physician (ticitl), more versed in magical procedures.

Some healers could even specialize in specific areas, finding examples in the Magliabecchi codex of physiotherapists, midwives or surgeons.

The traumatologist or »bone setter» was known as teomiquetzan, an expert especially in wounds and trauma produced in combat.

The tlamatlquiticitl or midwife monitored the pregnancy, but could perform embryotomies in the event of an abortion.

It is worth noting the use of oxytocics (uterine contraction stimulants) present in a plant, the cihuapatl.

Francisco López de Gómara, in his History of the Indies, also recounts the different medical practices encountered by the Spanish conquerors.

Classical antiquity

Again 3000 years before our era, on the island of Crete a civilization emerged that surpassed the Neolithic, using metals, building palaces and developing a culture that would culminate in the development of the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations.

These two cultures are the basis of Classical Greece, a major influence on the development of modern science in general and medicine in particular.

The development of the concepts of physis (nature) and logos (reasoning, science) suppose the starting point of a conception of the disease as an alteration of natural mechanisms, susceptible, therefore, to be investigated, diagnosed and treated, unlike the deterministic magical-theological model predominant up to that time.

The germ of the scientific method emerges, through autopsy ('vision for oneself') and hermeneutics (interpretation).

Greece

The classic term coined by the Greeks to define medicine, tekhne iatriké (the technique or art of healing), or those used to name the "doctor of diseases" (ietèr kakôn) and the surgeon (kheirourgein, 'hand worker') synthesize this concept of medicine as a science.

Human beings begin to dominate nature and allow themselves (even through their own myths) to challenge the gods (Anchises, Peleus, Lycaon or Odysseus).

The oldest written Greek works that include knowledge about medicine are the Homeric poems: the Iliad and the Odyssey.

The first describes, for example, how Fereclus is speared by Meriones in the buttock, "near the bladder and under the pubic bone", or the treatment King Menelaus receives after being hit by an arrow on the wrist during the siege of Troy: the surgeon turns out to be the physician Machaon, son of Asclepius, god of Greek medicine, educated in medical science by the centaur Chiron.

From his name derives Aesculapius, an ancient synonym for doctor, and the name of Hygea, his daughter, served as inspiration for the current branch of preventive medicine called hygiene.

Asclepius is also credited with the origin of the Rod of Asclepius, a universal medical symbol today.

In the VI century a. C. Alcmaeon of Crotona, a Pythagorean philosopher dedicated to medicine, developed a theory of health that was beginning to leave behind the pre-technical healing rituals that until then had founded Greek medicine: the prayer (eukhé) to the gods of health (Asclepius, Artemis, Apollo, Pallas Athena, Hygea,...), the dances or healing rites (Dionysus) and the empirical knowledge of basic remedies.

In Crotona, Cos or Cnido medical schools began to flourish following the concept of Alcmaeon, based on natural science, or physiology.

But the quintessential medical figure of classical Greek culture is Hippocrates. From this doctor it is known, thanks to the biography written by Sorano of Ephesus some 500 years after his death, that he was born in Cos around the year 460 BC. C. and his life coincides with the golden age of Hellenic civilization and its novel worldview of reason against myth. Galen and later the Alexandrian school considered him "the perfect doctor", for which he has been classically acclaimed as the Father of Modern Medicine.

Actually, the work attributed to Hippocrates is a compilation of about fifty treatises (Corpus Hippocraticum), written over several centuries (most of them between the V and IV BC), so it is more appropriate to speak of a "Hippocratic school", founded on the principles of the so-called Hippocratic oath. The medical fields covered by Hippocrates in his treatises include anatomy, internal medicine, hygiene, medical ethics or dietetics.

In his theory of the four humors, Hippocrates displays a concept, close to oriental medicine, of health as a balance between the four humors of the body, and of disease (nosas) as an alteration (excess or defect) of any of them. On this theoretical basis, he then develops a theoretical body of pathophysiology (how to get sick) and therapeutics (how to heal) based on the environment, the air, or food (the dietetics ).

The following two centuries (IV and III) marked the takeoff of the Greek philosophical movements. Aristotle learned medicine from his father, but there is no record of a regular practice of this discipline. Instead, his peripatetic school was the cradle of several important doctors of the time: Diocles of Caristo, Praxagoras of Cos or Theophrastus of Eresus, among others.

Around 300 B.C. C. Alexander the Great founded Alexandria, the city that in a short time would become the cultural reference point for the Mediterranean and the Near East. The Alexandrian school compiled and developed all the knowledge about medicine (as well as many other disciplines) known at the time, helping to train some outstanding doctors. Some sources point to the possibility that the Ptolemies made prisoners sentenced to death available to practice vivisections.

One of the most notable physicians of the Alexandrian school was Erasistratus of Ceos, discoverer of the common bile duct (duct that leads to bile in the small intestine), and of the portal circulation system (a venous system that crosses the liver with blood from the digestive tract).

Herophilus of Chalcedon was another of the great physicians of this school: he correctly described the structures called meninges, the choroid plexus and the fourth cerebral ventricle.

In parallel, the empiricist school developed, whose main medical exponent was Glaucus of Tarentius (I century BC).

Glauco could be considered the precursor of evidence-based medicine, since for him there was only one reliable basis: results based on his own experience, on that of other doctors or on logical analogy, when there were no data previous to compare.

From the incorporation of Egypt as a Roman province (30 BC), the Alexandrian period ends and the age of splendor of medicine in Rome begins.

Rome

Medicine in Ancient Rome was an extension of Greek medical knowledge.

The Etruscan civilization, before importing the knowledge of the Greek culture, had hardly developed a medical corpus of interest, except for a remarkable skill in the field of dentistry.

But the growing importance of the metropolis during the first periods of expansion began to attract important Greek and Alexandrian medical figures who ended up forming in Rome the main center of medical, clinical and educational knowledge in the Mediterranean area.

The most important medical figures in Ancient Rome were Asclepiades of Bithynia (124 or 129 BC–40 BC), Celsus, and Galen. The first, openly opposed to the Hippocratic theory of the humours, developed a new school of medical thought, the Methodical School, based on the works of Democritus, and which explains disease through the influence of the atoms that pass through the pores of the body, in a foretaste of the microbial theory.

Some doctors attached to this school were Themison of Laodicea, Thesalus of Trales or Sorano of Ephesus, the editor of the first known biography of Hippocrates.

Between 25 B.C. C. and 50 of our era lived another important medical figure: Aulo Cornelio Celsus. Actually there is no record that he practiced medicine, but a medical treatise (De re medica libri octo) is preserved, included in a larger work, of an encyclopedic nature, called De artibus (On the arts). This medical treatise includes the clinical definition of inflammation that has endured to this day: "Heat, pain, tumor, and redness" (sometimes also expressed as: "Tumor, redness, burning, pain").

At the beginning of the Christian era another medical school developed in Rome: the Pneumatic School. If the Hippocratics referred to liquid humors as the cause of disease and the atomists emphasized the influence of solid particles called atoms, the pneumatics would see in the pneuma (gas) that penetrates the organism through through the lungs, the cause of pathological disorders suffered by humans. Followers of this current of thought were Athenaeus of Atalia or Aretaeus of Cappadocia.

In Rome the medical caste was already organized (in a way reminiscent of the current division by specialties) into general practitioners (medici), surgeons (medici vulnerum, chirurgi), oculists (medici ab oculis), dentists and specialists in ear diseases. There was no official regulation to be considered a doctor, but based on the privileges granted to doctors by Julius Caesar, a maximum number per city was established.

On the other hand, the Roman legions had a field surgeon and a team capable of setting up a hospital (valetudinaria) in the middle of the battlefield to care for those wounded during combat.

One of these legionary doctors, enlisted in the armies of Nero, was Pedanio Dioscórides of Anazarbus (Cilicia), the author of the most widely used and well-known pharmacological manual up to the century XV. His travels with the Roman army allowed him to collect a large sample of herbs (about six hundred) and medicinal substances to write his great work: De materia medica ( Hylikà , known popularly as "the Dioscorides").

But the quintessential Roman medical figure was Claudius Galen, whose influence (and anatomical and physiological errors) lasted until the 16th century (the first to correct it was Vesalius). Galen of Pergamum was born in the year 130 of our era, under Greek influence and under the protection of one of the largest temples dedicated to Aesculapius (Asclepios). He studied medicine with two followers of Hippocrates: Straconius and Satyr, and still later visited the medical schools of Smyrna, Corinth, and Alexandria. He finally traveled to Rome where his fame as a gladiator doctor led him to be chosen as a physician to the emperor (Marcus Aurelius). However, in Rome autopsies were prohibited, so his knowledge of anatomy was based on animal dissections, which led him to make some mistakes. But he also made notable contributions: he corrected the error of Erasistratus, who believed that the arteries carried air, and is considered one of the first experimentalists in medicine:

Short and skillful is the path of speculation, but it does not lead anywhere; long and painful is the way of the experiment, but it leads us to know the truth.

He was the main exponent of the Hippocratic school, but his work is a synthesis of all the medical knowledge of the time. His treatises were copied, translated, and studied for the next thirteen centuries, making him one of the most important and influential physicians in Western medicine.

Areatheus of Cappadocia did not achieve the fame and public recognition of Galen, but the scant surviving written material of him demonstrates great knowledge and even greater common sense. Not many facts are known about this modest Roman doctor, except that he came from the current Turkish province of Cappadocia and that he lived during the first century after Christ. He must have trained in Alexandria (where autopsies were allowed), since his knowledge of visceral anatomy is very complete. He is the first doctor to describe the clinical picture of tetanus, and the current names of epilepsy or diabetes are due to him.

A major contribution of Roman public medicine must be highlighted: among the main Roman architects (Columella, Marco Vitruvio or Marco Vipsanio Agrippa) there was the conviction that malaria spread through insects or swampy water. Under this principle, they undertook public works such as aqueducts, sewers and public toilets aimed at ensuring a supply of quality drinking water and an adequate excreta evacuation system. Modern medicine will prove them right almost twenty centuries later, when it is shown that the drinking water supply and the sewage disposal system are two of the main indicators of the level of health of a population.

According to Henry Chadwick, emeritus regius professor at Cambridge University and historian of early Christianity, the practice of charity expressed eminently through the care of the sick was probably one of the causes most powerful of the expansion of Christianity. Already in the year 251, the Church of Rome supported more than 1,500 people in need. Despite the existence of early Roman field hospitals, the Empire lacked a social hospital awareness until the founding of the first large Christian hospitals. In the East, the Basiliade hospital was founded near Cappadocia (inspired by Basil of Caesarea), and another hospital in Edessa by Ephrem the Syrian, with three hundred beds for plague patients.

In the West, the nosocomium founded by Fabiola of Rome constitutes the first documented antecedent of "social medicine" and made her one of the most famous women in the history of organized medicine.

In that hospital, the poor were cared for free. Archaeological excavations revealed the plan and layout of this one-of-a-kind building in which the rooms and corridors for the sick and the poor were grouped in an orderly fashion around the main building body, organized into divisions, according to the different classes of sick. According to historian Camille Jullian, the founding of this hospital constitutes one of the sovereign events in the history of Western civilization.

Byzantium

The Eastern Roman Empire inherited, after the division by the death of Theodosius, Greek culture and medicine. In its eagerness to recover, or not to lose, classical knowledge, Byzantine culture played a fundamental role in compiling and cataloging the best of Greek and Roman traditions, making few novel contributions.

The personal physician of Julian the Apostate, Oribasius of Pergamum (325-403 AD) collected in 70 volumes (The Medical Synagogues) all the medical knowledge up to that date. Oribasio's advice, Juliano established the obligation to obtain an official (symbolon) license to practice medicine through an exam.

Continuing with this compiling spirit, but not very innovative, we find Alejandro de Trales (brother of the architect of the Basilica of Santa Sofia), or Aetius de Amida, in the VII.

The most notable doctor of this period was Paul of Aegina, author of Epítome, Hypomnema or Memorandum, seven volumes that collect the knowledge medicine, surgery and obstetrics. Among his contributions, the description of nasal polyps or joint synovial fluid stands out, and he described some novel surgical techniques, such as a technique to remove ribs.

Several medical schools were founded, such as the Stoa Basilike (School of Liberal Arts, in Constantinople), or the school of Nibisis, in Syria, the birthplace of doctors such as Zeno of Cyprus, Asclepiodotus or Jacobo Psychrestus, and in the V century, Theodosius II founded a center for intellectual training and dedicated various public buildings to healing the sick.

There is evidence of the existence of some other doctors and surgeons of a certain importance: Meletio, from the VII century, author from On the Constitution of Man; Theophanes Nonno (century X); Miguel Psellos and Simeón Seth in the XI century; or, between the 12th and XIII, Sinesio, Teodoro Pródromo or Nicolás Myrepso.

The reason for the stagnation of new advances in medicine from this period and during the Middle Ages responds to the growing importance of Christianity in political and social life, reluctant to the Hellenic concept of natural science and more prone to a deterministic vision (theocentric) of the disease.

Middle Ages

See Category:Medieval physicians

As societies developed in Europe and Asia, belief systems were being displaced by a different natural system.

All the ideas developed from ancient Greece to the Renaissance, passing through those of Galen, were based on the maintenance of health through the control of diet and hygiene.

Anatomical knowledge was limited, and there were few curative or surgical treatments.

Doctors based their work on a good relationship with patients, fighting small ailments and calming chronic ones, and they could do little against the epidemic diseases that ended up spreading halfway around the world.

Medieval medicine was a dynamic blend of science and mysticism. In the early Middle Ages, just after the fall of the Roman Empire, medical knowledge was largely based on surviving Greek and Roman texts preserved in monasteries and elsewhere.

Ideas about the origin and cure of diseases were not purely secular, but also had an important spiritual basis. Factors such as fate, sin, and astral influences carried just as much weight as the more physical factors. This is explained by the fact that since the last years of the Roman Empire, the Catholic Church has been acquiring an increasingly leading role in European culture and society. Its hierarchical structure performs a role of global civil service, capable of acting as a depositary and administrator of culture and of protecting and indoctrinating a population that the laws of the empire no longer reach.

Simultaneously, the monastic movement, coming from the East, began in the V century to spread throughout Europe.

In the monasteries, pilgrims, sick and hopeless were welcomed, beginning to form the germ of hospices or hospitals, although the medicine practiced by monks and priests lacked, in general, a rational basis, being more of a charitable nature than a technique.

At the Council of Clermont, in 1095, the study of any form of medicine was prohibited to all clerics.

There are antecedents of hospital structures in Egypt, India or Rome, but their extension and current conception is due to the monastic model initiated by Saint Benedict in Montecasino, and its later variants called leper colonies or lazarettos, in honor of their patron saint Saint Lazarus.

But the largest known hospital at the time was in Cairo; Al-Mansur, a hospital complex founded in 1283, was already divided into rooms for medical specialties. In the current way, it had a diet section coordinated with the hospital kitchen, a room for outpatients, a conference room, and a library.

Islamic World

After the death of Muhammad in the year 632, the period of Muslim expansion began. In barely a hundred years, the Arabs have occupied Syria, Egypt, Palestine, Persia, the Iberian Peninsula and part of India. During this expansion, by mandate of the prophet ("Seek knowledge even if you have to go to China"), the most relevant cultural elements of each territory are incorporated, in a short time going from practicing primitive medicine (empirical-magical) to dominating Hellenic technical medicine with a clear Hippocratic influence.

The first generation of highly reputable Persian physicians emerged from the Hippocratic Academy at Gundishapur, where the Nestorians, Christian heretics in exile, were engaged in the task of translating the major classical works from Greek into Arabic.. There the first batch of Arab doctors was formed, under the teachings of Hunayn ibn Ishaq (808-873), who would become the personal physician of Caliph Al-Qasim al-Mamun. From that position he founded the first medical school of Islam.

It was also there that the Persian Al-Razi (Abu Bakr Muhammed ibn Zakkariya al-Rhazi, also known as Rhazes) (865-932) began to use alcohol (Arabic al-khwl الكحول, or al-ghawl الغول) systematically in their medical practice. It is said of this doctor, founding director of the Baghdad hospital, that to decide his location he hung animal corpses in the four cardinal points of the city, opting for the location where decomposition took longer to occur.

Al-Razi's three main works are Kitab-el-Mansuri (Liber de Medicina ad Almansorem, synthesis of theoretical knowledge on anatomy, physiology, pathology); Al-Hawi (clinical compendium translated into Latin as Continens, Continence). In it he recorded the clinical cases he treated, which made the book a very valuable source of medical information; and the monographic work entitled Kitab fi al-jadari wa-al-hasbah, which contains an introduction to measles and smallpox that has a great influence on contemporary Europe.

Another of the representative figures of medieval Islamic medicine was Avicenna (Ali ibn Sina). The work of this Persian philosopher, entitled Canon of Medicine, is considered the most important medieval medical work in the Islamic tradition until its renewal with concepts of scientific medicine. It also had great influence throughout Europe until the arrival of the Enlightenment. If Rhazes was the clinician interested in diagnosing the patient, Avicenna was the Aristotelian theorist dedicated to understanding the generalities of medicine.

Several interesting medical figures from Al-Andalus should be highlighted, such as Avempace (ca. 1080-1138) and his disciple Abentofail, Averroes (1126-1198) or Maimonides, who, although Jewish, made an important contribution to the Arabic medicine during the XII century. Late 13th century and early XIV, also in Al-Andalus, Al-Safra, personal doctor of the entourage of Muhammad ibn Nasr (sultan of Granada), in his book Kitāb al-Istiqsā, provides various advances about tumors and drugs. Also noteworthy is the influence of Mesué Hunayn ibn Ishaq known for short by his Latin name as Johannitius or Mesué the Elder, who was a prominent translator of medical works in Persia due to his great ability or &# 39;gift of languages', and who wrote several studies of ophthalmology.

Ibn Nafis (Ala-al-din abu Al-Hassan Ali ibn Abi-Hazm al-Qarshi al-Dimashqi), Syrian physician of the 18th century XII, contributed to the description of the cardiovascular system. His discovery would be resumed in 1628 by William Harvey, to whom said finding is usually attributed. In the same way, many other medical and astronomical contributions attributed to Europeans took as their starting point the original discoveries of Arab or Persian authors.[citation required]

Abulcasis (Abul Qasim Al Zaharawi) is the first known surgical "specialist" in the Islamic world. He was born in Medina Azahara in the year 936 and lived in the court of Abderramán III. His main compilatory work is Kitàb al-Tasrìf (& # 34; the practice & # 34;, & # 34; the method & # 34; or & # 34; the provision & # 34;). Actually it is an expanded translation of Pablo de Aegina's, to which he added a lengthy description of the surgical instruments of the time, and was later translated into Latin) by Gerardo de Cremona. In this work he describes how to remove stones from the pancreas, eye operations, digestive tract, etc. as well as the necessary surgical material.

Another quote attributed to the Prophet Muhammad says that there are only two sciences: theology, to save the soul, and medicine, to save the body. Among Muslims Al Hakim (The Physician) was synonymous with "wise teacher". Arab doctors had the obligation to specialize in some field of medicine, and there were classes within the profession: From highest to lowest category we find the Hakim (the doctor of the maristan, hospital), the Tahib, the Mutabbib (practice doctor) and the Mudawi (doctor whose knowledge is merely empirical). Many of the medical figures and works of Islam had an important influence on medieval Europe, especially thanks to the translations, back into Latin, by the School of Translators of Toledo, or those of Constantine the African, who are at the origin of the first major European medieval medical school: the School of Salerno.

Europe

Between the 11th and XIII a medical school of special interest was developed south of Naples: the Salernitana Medical School. The privileged geographical situation of Campania, in southern Italy, never completely abandoned by culture after the fall of the empire, since it was a refuge for Byzantines and Arabs, allowed the emergence of this proto-university, founded according to legend, by a Greek (Ponto), a Hebrew (Helino), a Muslim (Adela) and a Christian (Magister Salernus), originally giving the name Collegium Hippocraticum.

In it, in order to obtain the title of doctor and, therefore, the right to exercise this practice, Roger II of Sicily established a graduation exam.

Some years later (in 1224) Frederick II reformed the exam so that it could be carried out publicly by the team of teachers from Salerno, and regulating a period of theoretical training for the practice of medicine (which included five years of medicine and surgery) and a practical period of one year.

A relevant figure of this school was the monk Constantine the African (1010-1087), a Carthaginian physician who collected numerous medical works throughout his travels and contributed to European medicine with the translation from Arabic of various classical texts. This work earned him the title of Magister orientis et occidentis.

Some of the works translated by Constantine are Liber Regius, by Ali Abas; the Viaticum, or 'travel medicine', by Ibn Al-Gazzar; the Libri universalium et particularium diaetarum or the Liber de urinis, highly influential in the Salerno school, to the point that the glass of urine became the distinctive sign of the doctor.

The orientation of the School of Salerno is fundamentally experimental and descriptive, and its most important work is the Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum (1480), a compendium of hygiene, nutrition, herbs and other therapeutic indications, which reached the figure of 1500 editions.

At the School, apart from medical teaching, there were also courses in philosophy, theology and law.

It is worth mentioning that in said school, women were admitted as teachers and as students, and were known as the Mulieres Salernitanae.

Its decline began at the beginning of the XIII century, due to the proliferation of medieval universities (Bologna, Paris, Oxford, Salamanca...).

One of the most fruitful sequels to Salerno can be found in the Chapter School of Chartres, where doctors such as Guillermo de Conches, precursor of scholasticism, along with Juan de Salisbury emerged.

The Faculty of Medicine of Montpellier located in France has existed since the XII century, although its first institutional framework was obtained in the year 1220. Its medical teaching was born in practice, outside any institutional framework. It is currently the oldest active medical school in the world. Illustrious people such as Arnau de Vilanova, François Rabelais or Guillaume Rondelet, among others, studied within it.

Among the most outstanding figures of medieval European medicine is the Spaniard Arnau de Vilanova (1238-1311). Trained in Montpellier and possibly also in Salerno, his fame led him to become a court physician to the kings of Aragon, Pedro the Great, Alfonso III and Jaime II. In addition to some translations of Galen and Avicenna, he develops his own body of medical research around tuberculosis (a form of presentation of tuberculosis). A collection of aphorisms in leonine verses from the XIII century known as Flos medicinae (or Flos sanitatis).

Within the theocentric conception typical of this period, alternative therapies of a supernatural nature are being introduced. From the VII and VIII, with the spread of Christianity, royal anointing rites were incorporated into coronation ceremonies, which grant a sacred character to the monarchy.

These anointed kings are credited with magical-healing properties. The most popular is the "king's touch": Philip the Fair, Robert II the Pious, Saint Louis of France or Henry IV of France touched the ulcers (scrofulas, or skin tubercular lesions) of the sick, pronouncing the ritual words "The king touches you, God heals you" (Le Roy te touche, et Dieu te guérit). French kings used to make a pilgrimage to Soissons to celebrate the ceremony and it is said that Philippe of Valois (1328-1350) came to touch 1,500 people in one day.

The popularization of this type of healing rites ended up renaming scrofula-tuberculosis as «mal du roi» in France, or «King's Evil » in England. Such was the profusion of this type of rites that "specialties" came to be established by monarchies; the King of Hungary's "specialty" was jaundice, the King of Spain's insanity, Olaf of Norway's goiter, and those of England and France scrofula and epilepsy.

In the XIII century Roger Bacon (1214-1294) anticipated in England the bases of empirical experimentation against the speculation. His maxim was something like “doubt everything you can't prove”, which included the main classical medical sources of information. In the Tractatus de erroribus medicorum he describes up to 36 fundamental errors of classical medical sources. But it would take two hundred years, until the arrival of the Renaissance, for his ideas to be put into practice.

Renaissance Medicine

Two historical events marked the way of practicing medicine, and even of getting sick, from the Renaissance on.

On the one hand, the great plagues that devastated and led the end of the Middle Ages. During the XIV century, the Black Death made its appearance in Europe, causing the death, by itself, of about 20 or 25 million Europeans.

On the other hand, the 15th (il Quattrocento) and 16th (il Cinquecento) centuries gave rise in Italy to philosophies of science and society based on the Roman tradition of humanism. The flourishing of Universities in Italy under the protection of the new mercantile classes was the intellectual motor from which the scientific progress that characterized this period was derived. This "new era" it stressed with special intensity in the natural sciences and medicine, under the general principle of "critical revisionism". The universe was beginning to be seen from a mechanistic perspective.

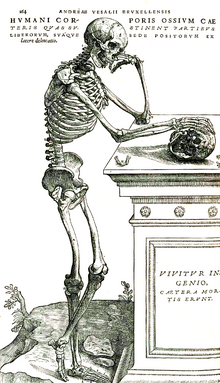

It is the time of the great anatomists: experimental evidence ends Galen's anatomical and physiological errors and Roger Bacon's advanced proposals reach all scientific disciplines: Copernicus publishes his heliocentric theory the same year that Andrés Vesalius, the leading anatomist of this period, published De humani corporis fabrica, his most relevant work and an essential manual for medical students for the next four centuries.

Vesalio received his doctorate at the University of Padua, after training in Paris, and was named "explicator chirurgiae" (professor of surgery) of this Italian university. During his years as a professor he will write his great work, ending his professional career as personal physician to Carlos I and, later, to Felipe II. He made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, as revealed in a letter from 1563, after his death sentence was commuted by the king for the penance of the pilgrimage. The reason for the sentence is the dissection that he carried out on a young Spanish nobleman after his death and the discovery, when opening his chest, that the heart was still beating.

But Vesalius is the result of a process that unfolded slowly from well into the 14th century. In 1316 Mondino de Luzzi, medieval by birth but Renaissance by right, published his Anathomia at the Bologna School, the first to make an anatomical description of a public dissection, giving way to a succession of treatises. anatomical and surgical in which medicine must reinvent itself as an empirical and proto-scientific discipline. Leonardo da Vinci himself published an innumerable catalog of illustrations, halfway between anatomy and art, based on dissections of at least twenty corpses, and the first classification of mental illnesses was published.

Vesalio's work saw two editions during the author's lifetime, and represented a conception of anatomy radically different from the previous ones: it is a functional anatomy, rather than a topographic one, glimpsing, in the description of the cavities of the heart, what will be the great anatomical and physiological discovery of the time: the pulmonary or minor circulation, which will be more completely formulated by two great Renaissance doctors: Miguel Servet (in Christianismi restitutio of 1553) and Mateo Realdo Colombo (in De re anatomica, 1559), and whose authorship has classically been attributed to the English physician of the XVIIth century William Harvey.

Due to his enormous influence, some eponyms have remained with the name of Vesalius in anatomical structures of the human body, such as the "Vesalius hole" (orifice of the sphenoid bone), the "vesalius vein" (pipe passing through Vesalius' hole), or the "Vesalius ligament" or Poupart's (on the lower edge of the aponeurosis of the major oblique muscle). The names of some of his disciples or his contemporaries, such as Gabriel Fallopio (1523-1562) or Bartolomeo Eustachio (1524-1574), also became anatomical eponyms.

In addition to anatomists in the Renaissance, some interesting medical figures also arose, such as Ambroise Paré, father of modern surgery, Girolamo Fracastoro and Paracelsus.

Paré perfectly represents the Renaissance model of a self-made doctor and reinventor of the role of medicine. He was from a humble family, but he achieved such fame that he ended up being the court physician of five kings. His training began in the barbers and toothpick guild, but he combined his work with attending the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris. He suffered some rejection from the medical community, since his humble background and his lack of knowledge of Latin and Greek led him to write all of his work in French. From the beginning he was considered a "renovator", which did not always benefit him, although his reputation was his main endorsement until the end. Much of his work is a compendium of analysis and refutation of customs, traditions or medical superstitions, without scientific foundation or real utility.

There would be little to highlight about the second, if it were not for a minor work written in 1546 that would not achieve repercussion until several centuries later: De contagione et contagiosis morbis. In it Fracastoro introduced the concept of "Seminaria morbis" (seed of disease), a rudimentary foretaste of the microbial theory.

And as for Paracelsus (Theophrastus Philippus Aureolus Bombastus von Hohenheim), his controversial personality (the self-proclaimed nickname Paracelsus took him for considering himself "superior to Celsus", the Roman physician) has placed him in a perhaps undeserved place in history: closer to alchemy and magic than to medicine. It is necessary to highlight, however, his critical study of the Hippocratic theory of humors, his studies on synovial fluid, or his opposition to the influence of scholasticism and his predilection for experimentation over speculation. In 1527 he proclaimed in Basel:

We will not follow the teachings of the old teachers, but the observation of nature, confirmed by a long practice and experience. Who ignores that most doctors take false steps to the detriment of their sick? And this just for sticking to the words of Hippocrates, Galeno, Avicena and others. What the doctor needs is the knowledge of nature and its secrets.

This position openly opposed to the most orthodox medicine, as well as his herbal studies, earned him the rejection of German doctors and, in general, of official medical historiography.

Some clinicians also stood out, such as the Frenchman Jean François Fernel, author of Universa Medicina, 1554, to whom we owe the term venereal: At the end of the century XV a syphilis pandemic occurred in Europe. The maximum extension of this epidemic (in 1495) occurred during the siege of Naples, defended by Italians and Spanish and besieged by the French army at the service of Carlos VIII. During the siege, French prostitutes spread the disease among mercenary armies and Spanish soldiers, giving the mysterious plague the name morbo gallico (disease of the French), and later as "sickness of love".

The Renaissance was also the time when psychology took off, with Juan Luis Vives, biochemistry with Jan Baptist van Helmont, or pathological anatomy: Antonio Benivieni compiled in his work De abditis morborum causis (Of the hidden causes of diseases, 1507) the results of the autopsies of many of his patients, comparing them with the symptoms prior to death, in the manner of modern scientific empiricism. The great figure of pathological anatomy, however, belongs to the next century: Giovanni Battista Morgagni.

The 17th century and the Enlightenment

At the beginning of the XVII century the medical profession did not yet enjoy excessive prestige among the population. Francisco de Quevedo expatiates against his incompetence and his greed in numerous verses:

Sangrate yesterday, purge today.Morning, suckers.

Francisco de Quevedo.

And it's another Kirieleyson.

Give the council money,

to whom he healed

by miracle or by venture,

Beard good, eat better.

Contradicting opinions.

Always blame the one who died

That it was messed up

and order your drill.

With this and good mule,

kill each year a pig

and twenty sick friends;

There are no Socrates like me.

But Isaac Newton, Leibniz and Galileo will give way in this century to the scientific method. While diseases such as diabetes are still classified according to the more or less sweet taste of the urine, or while smallpox becomes the new plague in Europe, technical and scientific advances are about to usher in a more effective and decisive era. Edward Jenner, a British doctor, observes that farmers who have suffered a mild disease from their cows, in the form of small blisters filled with liquid, do not contract the fearsome smallpox, and decides to carry out an experiment to test his hypothesis: With a lancet, he inoculates part of the fluid from a blister of a young woman infected with cowpox (variolae vaccine) to a boy named James Phipps, who volunteered for the experiment. After a few days he presents the usual symptoms: fever and some blisters. At six weeks he inoculates the child with a sample from a smallpox patient and waits. James Phipps will not contract the disease and since then this type of immunization has been known as a 'vaccine'.

William Harvey, an English physician, is the great physiologist of this century, official discoverer of blood circulation, neatly described in his Exercitatio anatomica de motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus (1628). In the last years of his life he also wrote some interesting embryological treatises. The most widespread theory about blood before the publication of Harvey's work is that it is constantly manufactured in the liver from food. But his observations show him that this is not possible:

the amount of blood that passes from the vena cava to the heart and from it to the arteries is overwhelmingly superior to that of the ingested food: The left ventricle, whose minimum capacity is ounce and half blood sends the aorta in each contraction no less than the eighth part of the blood it contains; therefore every half hour come out of the heart about 3000 dracmas of blood (about 12 kg), amount infinitely greater than the liver.

Harvey adopts a more vitalist vision compared to Renaissance mechanism: living beings are animated by a series of determining forces, which are at the origin of their physiological activity, susceptible to study from a scientific perspective, but all of them subject to a superior vis (force), origin of life, although not necessarily of a divine nature.

During this century, experimentation advanced at such a pace that the clinic was unable to absorb it. Academies of experts for the transmission of information obtained from continuous findings begin to be founded: the Academia dei Lincei in Rome, the Royal Society in London, or the Académie des Sciences in Paris. As a result of the multiple and innovative therapeutic proposals, iatrochemistry emerges as a discipline with its own entity, whose main exponent is Franciscus Sylvius, heir to the chemical perspective of medicine anticipated by Helmont.

Important physicians attached to this iatrochemical school were Santorio Sanctorius or Thomas Willis. Santorio was the author of a study that placed him at the beginning of a long list of endocrinologists, being the first to define metabolic processes: The first controlled experiment on human metabolism was published in 1614 in his book Ars de statica medicine. Santorio described how he weighed himself before and after sleeping, eating, working, having sexual intercourse, drinking, and excreting. He found that most of the food he ate was lost in what he called "insensible perspiration." Like Harvey, Santorio attributed these processes to a "vital force" that animated living tissue.

Vitalism developed as a philosophical approach and found followers among doctors and naturalists, reaching its peak in the middle of the 18th century, by the hand of Xavier Bichat (1771-1802), John Hunter (1728-1799), François Magendie (1783-1855) or Hans Driesch (1867-1941).

Thomas Willis, in his work Cerebri anatomi (1664), described several cerebral anatomical structures, among them the vascular polygon of Willis, named after him; but technical improvements, such as the microscope, gradually increased the level of detail of the anatomical descriptions and soon the eponymous structures baptized by their discoverers or by later historians proliferated: Johann Georg Wirsung (who gives his name to the excretory duct of the pancreas), Thomas Wharton (Wharton's duct is excretory from the submandibular salivary gland), Nicolás Stenon (Stenon's duct: excretory from the parotid gland), Caspar Bartholin, De Graaf and many others.

Another notable physician from this period is Thomas Sydenham, nicknamed the English Hippocrates. A born clinician more interested in semiology (the description of symptoms as a diagnostic method) than in experimentation, and who also left his name associated with diseases such as Sydenham's Chorea. In his treatises, the concept of morbid entity is raised, a very current concept of disease, understood as a process originating from the same causes, with a similar clinical and evolutionary picture and with a specific treatment. This concept of disease will complete it, thanks to the microscopic anatomical descriptions of him Giovanni Battista Morgagni. Morgagni, a disciple of Antonio María Valsalva, stood out from a young age due to his medical concerns. His most important work is & # 34; De sedibus et causis morborum per anatomen indicatis & # 34; published in 1761 and in it he describes more than 700 clinical histories with his autopsy protocols. To his credit is the novel (and correct) proposal that tuberculosis was an infectious disease, therefore susceptible to being contracted through contact with patients. This theory will take time to be demonstrated by Robert Koch, but it originates the first social movements of "quarantine"; in specific institutions for patients with this disease.

Marcello Malpighi also knew how to take advantage of the improvements developed by Anton van Leeuwenhoek in the microscope. The descriptions of his tissues observed under magnification have earned him the title of father of histology. In his honor some renal structures called Malpighian pyramids have been baptized.

The enlightened despotism inspired a vertical humanism that is at the origin of social medicine (antecedent of public health), whose first great success was the implantation of the smallpox vaccine after the discovery from Jenner. That same humanism will be the inspiration for the first works in medical ethics (Thomas Percival) and the first studies on the history of medicine. Notable surgeons of this time include Pierre Dessault or Dominique-Jean Larrey (Napoleon's surgeon) in France and John Hunter in England.

With the industrial revolution, a series of social and economic circumstances arose that once again promoted the medical sciences: on the one hand, the migratory phenomena of large population masses that crowded into cities are inaugurated, with the corresponding unhealthy consequences: poor diet and development of diseases related to it (pellagra, rickets, scurvy...) and proliferation of infectious diseases (especially tuberculosis). But the technical conditions also exist for the discoveries noted during the Enlightenment to see their technical development fulfilled and improved: The XIX century It is going to be the century of public health, asepsis, anesthesia and the definitive victory of surgery.

The 19th century

Medicine of the 19th century still contains many elements of art (ars medica), especially in the field of surgery, but thanks to the unstoppable achievement of knowledge and techniques, a more scientific way of exercising it is beginning to emerge and, therefore, more independent of "ability" or the experience of those who practice it. This century will see the birth of the theory of evolution, an anthropological expression of its own scientific positivism. Reality can be measured, understood and predicted through laws, which in turn are corroborated by successive experiments. Astronomy (Laplace, Foucault), physics (Poincaré, Lorentz), chemistry (Dalton, Gay-Lussac, Mendeleev) and medicine itself advance along this path.

The quintessential medical figure of this period was Rudolf Virchow. He developed the disciplines of hygiene and social medicine, at the origins of current preventive medicine. It is Virchow himself who postulated the theory of "Omnia cellula a cellula" (every cell comes from another cell) and explained living organisms as structures made up of cells. Shortly before his death, in 1902, he will be a candidate for the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology, together with the Spanish Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who will finally obtain the award in 1906.

The last decades of the XIX century were of great importance for the development of contemporary medicine. Joseph Skoda and Carl von Rokitansky founded the Modern School of Medicine in Vienna (Neue Wiener Schule), the cradle of the new batch of medical figures of this century. Skoda is considered the main exponent of "therapeutic nihilism", a medical current that advocated abstaining from any therapeutic intervention, leaving the body to recover on its own or through appropriate diets, as the treatment of choice for many diseases. He was a noted dermatologist and clinician, achieving fame for his brilliant, accurate, and prompt diagnoses. To him is due the recovery and expansion of diagnostic techniques through percussion (advanced by Leopold Auenbrugger a century earlier), and in 1841 he created the first dermatological department together with Ferdinand von Hebra, the master of dermatology of the century XIX.

Rokitansky is considered by Rudolf Virchow "the Linnaeus of pathological anatomy" due to his descriptive meticulousness, which ended up giving names to several diseases described by him (Rokitansky tumor, Rokitansky ulcer, Rokitansky syndrome...).

In 1848 Claude Bernard, the great physiologist of this century and "founder" official of experimental medicine, discovers the first enzyme (pancreatic lipase). In that year, ether began to be used to sedate patients before surgery and at the end of this century Luis Pasteur, Robert Koch and Joseph Lister would unequivocally demonstrate the etiological nature of infectious processes through the microbial theory. In France and Germany, biochemistry is developed, a branch of biology and medicine that studies the chemical reactions involved in vital processes. From here the studies on vitamins will arise and the foundations of modern nutrition and dietetics will be laid.