History of japan

The History of Japan (日本の歴史 or 日本史 , Nihon no rekishi / Nihonshi?) is the succession of events that occurred within the Japanese archipelago. Some of these facts appear isolated and influenced by the geographical nature of Japan as an insular nation, while another series of facts is due to foreign influences as in the case of the Chinese Empire, which defined its language, its writing and, also, its their political culture. Likewise, another of the foreign influences was that of Western origin, which turned the country into an industrial nation, thereby exercising a sphere of influence and territorial expansion over the Pacific area. However, this expansionism stopped after the Second World War and the country positioned itself as an industrial nation with ties to its cultural tradition.

The appearance of the first human inhabitants in the Japanese archipelago dates from the Paleolithic period approximately 35,000 years ago. Between 11,000 and 500 BCE. These inhabitants developed a type of pottery, called "Jōmon", considered the oldest in the world. Later, a culture known as "Yayoi" appeared, which used metal tools and grew rice. In it there were several chiefdoms, although that of Yamato would stand out. In later centuries the rulers of Yamato strengthened their position and began to expand throughout the archipelago under a centralized system, subduing the various existing tribes, claiming their divine descent. At the same time, the central government began to assimilate Korean and Chinese customs. The rapid imposition of foreign traditions produced a tension in Japanese society and in the year 794 the imperial court founded a new capital, Heian-kyō (present-day Kyoto), giving rise to a highly sophisticated culture of its own from the aristocracy. However, in the provinces the centralized system was a failure and a land privatization process began, resulting in a collapse of the public administration and the breakdown of public order. The aristocracy began to need the help of warriors to protect their properties, giving rise to the samurai class.

Minamoto no Yoritomo assumed the leadership of Japan in 1192, establishing the figure of the shogunate as a permanent military institution that would govern de facto for almost 700 years. The outbreak of the Ōnin War in 1467 sparked a chain of wars that spanned Japan, a period that culminated in 1573, when Oda Nobunaga began to unify the country, but was unable to finish the task due to being betrayed by one of his chiefs. generals. Toyotomi Hideyoshi avenged his death and completed the unification in 1590. Upon his death, the country again divided into two factions, those who supported his son Hideyori and those who supported one of the daimyō Major, Tokugawa Ieyasu. Both sides clashed during the battle of Sekigahara, from which Ieyasu emerged victorious, being officially named shōgun in 1603, establishing the Tokugawa shogunate. The Edo period was characterized by being peaceful, and by the decision to close the borders to avoid contact with the outside world. Isolation ended in 1853 when Commodore Matthew Perry forced Japan to open its gates and sign a series of treaties with foreign powers (called "Unequal Treaties"), causing unrest among some samurai, who supported the emperor to retake his role in politics.

The last Tokugawa shōgun resigned in 1868, ushering in the Meiji era, named after the reigning emperor who assumed political power. The modernization of the country began, abandoning the feudal system and that of the samurai, the capital was transferred to Tokyo, a strong process of westernization began and Japan would emerge as the first industrialized Asian country. A process of territorial expansionism towards neighboring nations arose, which led them to confront the Russian Empire and the Chinese Empire militarily. At the death of Emperor Meiji, Japan had become a modern, industrialized state with a central government and as a power within Asia, rivaling the West. There was a social explosion due to economic and population growth and political extremism began to gain ground and towards the 1930s military expansion accelerated, confronting China for the second time. After the outbreak of the war in Europe, Japan took advantage of the situation to annex other parts of Asia. During the year 1941, diplomatic relations between Japan and the United States were tense, since US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had blocked oil supplies to Japan and had frozen all Japanese credits in the United States. On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, bringing Japan into World War II as part of the "Axis Powers." Despite a series of initial victories, defeats to the Allies in battles such as Midway turned the tables on the Pacific scene. After the terrible atomic bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan submitted its unconditional surrender, so it was occupied by US forces, which dismantled the army, liberated the occupied areas, the Emperor's political power was suppressed and the prime minister would be elected by the Parlament.

In 1952 Japan regained its sovereignty after the signing of the Treaty of San Francisco and grew economically with the help of the international community. Politically, the conservative Liberal Democratic Party ruled almost uninterruptedly after the war. With the onset of the Heisei era, Japan suffered an economic recession in the 1990s and socially faced declining birth rates and a rapidly aging population. In the early years of the 21st century, Japan has begun to reform post-war practices in society, government, and the economy.

Periodization

For its study, the history of Japan is divided into large periods in terms of artistic production and important political developments. The classification usually varies depending on the author's criteria, in addition to the fact that many of them can be subdivided. On the other hand, there are also divergences regarding the beginning and end of some of these periods. The classification made by archaeologist Charles T. Keally is as follows:

| Historical periods in Japanese archaeology | ||

|---|---|---|

| Prehistory | Paleolithic | 50/35 000-13/9500 a. P. |

| Jōmon | 13/9500-2500 a. P. | |

| Yayoi | 500 a. C.-300 | |

| Kofun | 300-710 | |

| Antigua (LICITIAL, Kodai?) | Nara | 710-794 |

| Heian | 794-1185 | |

| Medieval (中文, Chūsei?) | Kamakura | 1185-1392 |

| Muromachi | 1392-1573 | |

| Early Modern or Premodern (, Kinsei?) | Azuchi-Momoyama | 1573-1600 |

| Edo | 1600-1868 | |

| Modern (أعربية , Kindai / Gendai?) | Meiji | 1868-1912 |

| Taishō | 1912-1926 | |

| Shōwa | 1926-1989 | |

| Heisei | 1989-2019 | |

| Reiwa | 2019-presente | |

You were Japanese

The nengō (年号, 'nengō'?) suppose another division of its history according to the reigning emperor. The era classification system is based on the emperor's name, followed by the year corresponding to his tenure. For example, 1948 corresponds to the year Shōwa 23. Japan currently uses both the Gregorian calendar and the nengō system, although this system is rarely used in Western literature.

History

Paleolithic Period in Japan

By definition, the Paleolithic period in Japan ended with the appearance of the first ceramic techniques, at the end of the last glacial period, 13,000-10,000 years ago. Q. The dating of the beginning of the Paleolithic is widely controversial, although it is generally accepted that this period was found between the years 50/35,000-13/9,500 BC. Q.

The Late Paleolithic, dating from the excavation of the Iwajuku site in 1949 and from which extensive information has been obtained since the 1960s, can be divided into the following traditions and phases:

| Traditions | Fases | Dates |

|---|---|---|

| Cutting edge tools | Phase Ia | 35 000-27 000 a. P. |

| Phase Ib | 27 000-23 000 a. P. | |

| Phase Ic | 23 000-21 000 a. P. | |

| Size tools | Phase IIa | 21 000-16 000 a. P. |

| Phase IIb | 16 000-13 000 a. P. | |

| Microlithic work | Phase III | 13 000-12 000 a. P. |

| Projectile bifacial tip | Phase IV | 12 500-11 000 a. P. |

| Jōmon incipient | 13 000-9500 a. P. | |

There is little evidence about how the people of Japan lived during this period, other than the presence of humans before 35,000 B.C. P. is controversial. The transition between this and the following period was gradual and no evidence of a clear break or non-conformity between the two cultures has been found.

It is known that the first inhabitants were hunter-gatherers from the mainland who used stone, but did not possess pottery or sedentary agriculture.

Jomon Period

The Jōmon period (縄文時代, Jōmon-jidai?) differs from the previous one by dating the appearance of ceramics in the country, commonly associated with early agricultural cultures. During the first 10,000 years after its appearance, approximately from 11,000 to 500 B.C. C., the subsistence of the inhabitants depended mainly on hunting, fishing and gathering.

This period takes its name precisely from the type of pottery developed, its meaning being “rope mark”, a distinctive mark left by the ropes on wet clay, which was formed with strips of clay fired at low temperatures. According to its dating, ceramics from this period are the oldest in the world.

Archaeologically, this stage is divided into six sub-periods as follows:

| Subperiods | Dates |

|---|---|

| Jōmon incipient | 11 000-7500 a. C. |

| Initial Jōmon | 7500-4000 a. C. |

| Jōmon early | 4000-3000 a. C. |

| Jōmon | 3000-2000 a. C. |

| Jōmon late | 2000-1000 a. C. |

| Jōmon final | 1000-500 a. C. |

Yayoi Period

The culture of the Yayoi period (弥生時代, Yayoi jidai?) is defined in Japan as the first to implement rice cultivation methods as well as the use of metal, although archaeologically it is classified by identifying certain artifacts, especially ceramic styles. This era is generally considered to have spanned from 500 B.C. C. until 300 of our era, and is divided into three sub-periods:

| Subperiod | Ceramic phases in northern Kyūshū | Ceramic phases in the plains of Kantō | Ceramic phases in Aomori | Ceramic phases in Hokkaidō |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yayoi early 500-100 a. C. | Itazuke I | Jōmon late | Sunasawa | Epi-jomon |

| Itazuke II | - | Seno | ||

| Jonokoshi | - | Nimaibashi | Esan I | |

| Yayoi half 100 a. C.-100 d. C. | Sugu | Osagata | Inakadate 1 | Epi-jomon |

| Mitoko | Suwada | Inakadate 2 | ||

| Takamizuma | Miyanodai | Nembutsuma | Esan II-IV | |

| Yayoi late 100-300 | Shimo-Okuma | Kugahara | Oishitai | Epi-jomon |

| Nobeta | Yayoicho | Chitose | ||

| Nishijin | Maenocho | Chokaisan | Kohoku B, C |

The members of the Yayoi culture were extremely different physically from those of the Jōmon culture, so there are three theories about the origin of the Yayoi:

- They were descendants of the Jōmon, although they suffered physiological changes due to the change in their diet and way of life.

- They were immigrants from the continent (via Korea).

- They were descendants of the mix between Jōmon and immigrants.

The use of metal diversified, including everything from bronze swords, mirrors for religious rites, and iron weapons to agricultural tools. With the division of labor a deep stratification arose in society, establishing the ruling classes and their subjects, and giving origin to territories or chiefdoms.

At the end of this period there were a large number of chiefdoms, one of the most important being Yamatai-koku, which would lay the foundations of the emerging nation during the following period, and whose existence is recorded in the Chronicles of Wei. These chronicles record the existence of a nation known in China as "Wa" under the leadership of a woman named Himiko; probably Empress Jingū.

Kofun Period

The Kofun period (古墳時代, Kofun jidai?) takes its name from the kofun (古墳, 'kofun&# 39;? lit. "old tomb" or "old burial mound"); burial mounds in which members of the aristocratic class were buried along with their bronze weapons, armor, and mirrors, and which were usually in the shape of a keyhole. The bases of these mounds varied in size, some reaching as high as be as large as those of the Egyptian pyramids, reflecting the magnitude of the rulers' power.

During this period, Japan had a lot of contact with China and Korea, especially the latter. During the year 400, an army of infantry came to the aid of the kingdom of Paekche, located in the southeastern part of the Korean peninsula, but suffered a major defeat at the hands of the Koguryŏ kingdom's cavalry, coming from the north of the peninsula.

The Kofun period marks the end of prehistory, and due to the lack of Japanese records, the history of this time depends on outside sources (first Korean and later Chinese chronicles) as well as early writings. from the Nara period, around the 8th century. Although there are no writings from China mentioning Japan between the years 266 and 413, Korean records from the 4th century provide ample information on the activities of the Wa kingdom on the Korean peninsula. On the other hand, Chinese records, dated to the 5th century, show the close relationship between the emerging Yamato government (located in present-day Nara Prefecture) and China. Between the years 413 and 502, the five kings of Wa, the name by which five monarchs of Japan are mentioned, maintained a close relationship with that country, continually sending emissaries.

The Kofun period is generally dated to between the years 250/300-538/552, the beginning being marked by the construction of the first kofun and the end by the date Buddhism is considered to have was introduced to Japan. On the other hand, various historians and archaeologists, such as the case of Charles T. Keally, extend the period to the year 710, so the Asuka and Hakuhō periods would be considered sub-periods of the Kofun.

According to Keally's dating, the chronology of the period would be as follows:

| Chronology | Dates |

|---|---|

| Kofun early | Ends of the III-century IV |

| Kofun half | End of the centuryIV- century V |

| Kofun late Asuka (552-646) Hakuhō (646-710) | century VI-century VII |

The Yamato court government focused on a Kimi (君, ' Kimi'? «king»), but at From the V century the ruler was called Ōkimi (大君, 'Ōkimi'? "great king"). The title Tennō (天皇, 'Tennō'? "emperor"), which is used to this day, was used from the mandate of Emperor Tenmu.

Asuka Period

The Asuka period (飛鳥時代, Asuka jidai?) is marked by the introduction of Buddhism in Japan, generally dated to the year 552. The arrival of this religion brought with it a series of conflicts within the country, as some members of the court welcomed its spread, considering that through its implementation national unity would be more easily achieved: it was easier to establish a new religious hierarchical base under the figure of an omnipotent deity (Buddha), unlike the hundreds of kamis of the Shintō or Shinto. The conflict ended with the victory of Soga no Umako in 587, as well as the subsequent adoption of Buddhism as the official religion by Prince Shotoku and Empress Suiko in 593. Interestingly, Buddhism did not replace Shinto, but instead both religions coexisted peacefully for most of the history of this country.

Prince Shotoku established a centralized government, and the Japanese court built temples, palaces, and capitals based on Korean and later Chinese models. Shotoku was fascinated by these nations, which is why he promoted the use of Chinese characters (which would give rise to the kanjis), laid the foundations for the development of codes of conduct and government ethics based on Buddhism (Seventeen Articles Constitution, 604) and sent embassies to Sui Dynasty China (600 to 618) in order to establish equal diplomatic relations.

In 602, Prince Kume led an expedition to Korea accompanied by between 120 and 150 local chieftains, who held the title of Kuni ni Miyatsuko. Each of them was accompanied by a personal army, of variable size depending on the wealth of each fief. These troops constituted what would be the prototype of a samurai army centuries later.

Art at this time focused on fine Buddhist art, with the main work being the Buddhist temple of Hōryū or Hōryū-ji, commissioned by Prince Shotoku at the turn of the century VII and that it is the oldest wooden structure in the world.

Hakuhō Period

After the death of Prince Shotoku in 621, a clan called the Soga arose within the court, slowly gaining political power and posing a threat to the imperial government. By 645 the situation was so critical that Prince Naka no Ōe, along with others, organized a plot (Isshi Incident) in which the prince assassinated the clan leader, Soga no Iruka in full audience with Empress Kōgyoku. As a consequence, the empress immediately capitulated, her younger brother, Emperor Kōtoku, ascended the throne, and the Soga clan was destroyed. The new emperor, together with Nakatomi no Kamatari and Prince Naka no Ōe, wrote a series of laws called the Taika Reforms in the year 646 in order to strengthen the central government, establish land reform, restructure the imperial court on the Chinese model of the Tang Dynasty, and even the sending of embassies and students to China was motivated in order to imitate cultural aspects of this country, radically affecting the culture and its society. This period is known as Hakuhō (白鳳文化, Hakuhō bunka?) .

After the deaths of Emperor Kōtoku (in 654) and Empress Kōgyoku (who resumed the throne as Empress Saimei, dying in 661), Prince Naka no Ōe assumed the throne as Emperor Tenji, who formally promulgated the first ritsuryō (compilation of laws based on Confucianist philosophy and Chinese laws); the Ōmi Code (669). Nakatomi no Kamatari, who wrote the code, was rewarded by receiving the surname Fujiwara, and would become the founder of the Fujiwara clan.

After the application of the ritsuryō, the formerly powerful clans were deprived of their privileges and turned into high-ranking bureaucrats, while the lower layers of the former elite became local officials..

Wars continued to occur in China and Korea. In the year 618 the Tang dynasty seized power in China, and they joined the Korean kingdom of Silla in order to attack Paekche. The Japanese sent three expeditionary armies (in 661, 662, and 663) to help the Paekche kingdom. During these expeditions they suffered one of the worst defeats in their ancient history, losing 10,000 men and numerous ships and horses. Japan began to worry about an invasion by the new alliance between Silla and China. In 670 a census of the population was ordered to recruit elements for the army. In addition, the northern coast of Kyūshū was fortified, guards were posted, and beacons were built on the shores of Tsushima Islands and Iki Island.

The Japanese forgot about external warfare when Emperor Tenji died in 671. In 672 his two successors fought for the throne in the Jinshin War. After Emperor Tenmu's triumph in 684, he ordered all civil and military officers to master martial arts. Emperor Tenmu's successors culminated in the year 702 military reforms with the Taihō Code (大宝律令, Taihō-ritsuryō?), through the which a large and stable army was achieved according to the Chinese system. Each heishi (soldier) was assigned to a gundan (regiment) for part of the year and the rest was devoted to agricultural tasks. Each soldier was equipped with bows, a quiver, and a pair of swords.

Establishment of the imperial system

During this time, in the 8th century, the governors of Yamato ordered that existing myths be recorded as a way of legitimizing themselves in front of the population. The most important of these legends is the one referring to the creation of Japan, attributed to the kami Izanagi and Izanami. According to legend, these two would have born the three older kami: Amaterasu —goddess of the sun and lady of the skies—, Susanoo —god of the oceans— and Tsukuyomi —god of darkness and darkness. Luna. One day Amaterasu and Susanoo argued, so Susanoo got drunk destroying everything in his path. Amaterasu was so scared that she hid in a cave refusing to come out, thus the world was deprived of light. In order to force her out, a female kami, Ame-no-Uzume, performed an obscene dance that was accompanied by laughter from the myriad gods who were assembled in assembly. When Amaterasu asked what was happening, they told her that there was a more powerful kami, so she left the cave and slowly approached a mirror that was placed in front of her. her surprise at seeing her own reflection, which was dazzled for a few moments and then they took the opportunity to capture it and the light illuminated the Earth again, so the mirror was part of the Imperial Insignia of Japan.

The second element of the three Japanese Crown Jewels is described later in the same legend. Susanoo was banished for the evils caused and while he was wandering through the lands of Izumo he heard that an eight-headed serpent, called Yamata-no-Orochi, was frightening the inhabitants. Susanoo killed the snake by making it drunk with sake and lopped off its heads. In his tail was found a sword, which he decided to give to his sister as a sign of peace. This sword represents the second icon of the imperial regalia.

The third and final insignia is a curved jewel, which Amaterasu gave to her grandson Ninigi when he was sent to the underworld to rule. The jewel passed in turn to his grandson, Emperor Jinmu, the first Japanese emperor. In this way, supported by popular beliefs, the governors of Yamato legitimized the process by which Japan would be governed by an imperial system, strongly supported by the Shintō belief.

Nara Period

The Nara period (奈良時代, Nara-jidai?) is generally dated between the years 710, when the capital was transferred to Heijō-kyō, near the city of Nara, and ends in the year 794, when the capital was transferred again to Heian-kyō, in what which is now Kyoto. In this period the Chinese bureaucratic state reached its climax: the new capital was built in the fashion of the Tang dynasty capital, Chang'an. Buddhism and Confucianism prospered, under the patronage of the government, and were used to support political power and temples were built both in the capital and in each of the provinces. Chinese cultural influence became more evident and literature appeared with the first historical records compiled by the Imperial Court: the Kojiki (712) and the Nihonshoki (720). The appearance of written language also gave rise to the first manifestation of Japanese poetry, the waka, and in 759 the first important compilation was made; the Man'yōshū.

However, the Chinese system did not fit in with Japanese society, and disputes in the Imperial Court were common between members of the imperial family, the Fujiwara clan, and Buddhist monks. Fujiwara no Fuhito, son of Kamatari and a powerful bureaucrat within the court, compiled the Yōrō Code in 720, but his death that same year led to a division of power among his sons. Prince Nagaya seized the moment, but Fuhito's sons arrested him and sentenced him to death in 729. However, a few years later Fuhito's sons died after an epidemic of smallpox, attributed to a curse the prince cast before die. This caused Emperor Shōmu to move to various cities that were briefly declared capitals between 740 and 745, before returning to Nara.

After the abdication of Emperor Shōmu in 749, the Buddhist clergy seized power with the support of Empress Kōken who, although she abdicated in 758, continued to exercise power over the court, favoring an important Buddhist monk named Dōkyō. This caused the Fujiwara clan and Emperor Junnin to attempt a coup in 764 that failed, leading to the deposition of the emperor and the execution of Fujiwara no Nakamaro, leader of the conspiracy. The empress resumed the throne as Empress Shotoku, continuing to cede power to Dōkyō, who was even named by an oracle as successor to emperor. However, the empress died of smallpox in 770, Dōkyō he was exiled and a new course in politics was initiated by expelling Buddhist monks from the government and suspending government sponsorship of the religion. The measures promoted by Emperor Kōnin (770-781) and by Emperor Kanmu (781-806) finally made the imperial court leave Nara, considering it unhealthy and with the aim of disconnecting from the Buddhist temples that existed in the city. They first moved temporarily to Nagaoka-kyō in 784 and finally to the new capital Heian-kyō ("Capital of Peace and Tranquility") in 794.

With the birth of the Unified State of Silla, the threat of a Korean invasion of Japan disappeared, so the Court of Nara focused its attention on the emishi (蝦夷, 'emishi'? "barbarians"), inhabitants of northern Japan with whom they had had numerous altercations. In 774 a major revolt broke out, known as the Thirty-Eight Years' War, where the emishi used a system of "guerrilla warfare" and a curved-blade sword, which performed best when sharpened. he rode, unlike the straight sword of the Nara Court army. It was not until 796, through Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, that they were finally defeated. Sakanoue was given the title of Seii Taishōgun (征夷大将軍, 'Seii Taishōgun'? "Great General Appeaser of the Barbarians"), an expression that would later be used to designate the leader of the samurai.

The peasant enlistment system ended in 792, recognizing that the main military force came from the caciques and their soldiers and not from the peasants who did not have adequate training and discipline for the battlefields.

Heian Period

The Heian period (平安時代, Heian jidai?) began with the establishment of the capital in the year 794 in what is now Kyoto, and its end is marked by the establishment of the first shogunate in the country's history: The Kamakura.

Consolidation of the aristocracy

In this period, the Chinese state framework was modified and adapted to Japanese needs, giving rise to its own sophisticated culture. With the decline of the rigid bureaucratic system of the Taika and Taihō codes, the imperial institution was strengthened in the early years from the reign of Emperor Kanmu, but after his death in 806 cultural assimilation with China was gradually abandoned and around 838 relations with the Tang dynasty were terminated. Also, with the disappearance of the old political system, the Fujiwara clan began a process of monopolizing the upper hierarchies of the government from the first half of the 9th century, establishing close matrimonial ties with the imperial family. The clan leaders positioned themselves in such a way that they became regents (sesshō and kanpaku) of the emperors, while other members of the Fujiwara clan managed to monopolize higher positions such as the of the Council of State (Daijō-kan). Middle and low-ranking officials were distributed hereditarily by other aristocratic clans. Towards the end of the 10th century and the beginning of the 11th century, the Fujiwara ruled de facto Japan and very few emperors ruled on their own, as they assumed the throne and were forced by clan chiefs to abdicate at a very young age, leaving administrative decisions to regents and Daijō-kan.

Esoteric Buddhism of the Tendai and Shingon sects became very popular in this period and aristocrats sought "salvation" through ceremonies and rites. There was a sophistication of Japanese culture, which until then was handled with Chinese ideographic writing, having the imperial court as its central axis. There was an amazing literary breakthrough with the creation of kana, a syllabic script that conformed to Japanese phonetics. New genres such as the novel (monogatari) were established, with the Murasaki Shikibu's Genji Monogatari, written around the year 1000, diaries, essays, and other personal writings by courtiers such as Sei Shōnagon's Makura no Sōshi, also written around the year 1000.

In the military field, around 860, most of the characteristics of the future samurai warriors could be appreciated: riders on horseback skilled in the use of the bow, in addition to the use of curved-blade swords. These soldiers on horseback enjoyed of the total confidence of the "Throne of the Chrysanthemum" and were in charge of the security of the cities as well as fighting against the revolts that occurred.

However, the public land system that extended over the provinces was about to collapse, so in many places private land (shōen) was created that was used in the first instance by the aristocracy and the great temples. With the suspension of family registration and the allocation of arable land around the X century, state land was integrated into private land Owners of private land appointed local clans and peasants as administrators, eventually transferring power to them. However, the existence of numerous private estates significantly reduced taxes and it got to the point that the imperial family itself was forced to obtain private land to secure such income.

Rise of the samurai class

The decentralization process that the government underwent made the execution of local administration difficult, resulting in the eventual breakdown of law and public order. During the century IX Japan suffered a severe economic decline as a result of plagues and various famines and at the turn of the century X numerous riots, riots and rebellions took place due to the current situation. The government made the decision to grant broad powers to local governors to recruit troops with sword fighters (katana), archers, and cavalry, enlisting peasants as their followers, and act against the growing rebellions as to what they saw fit, which gave these governors enormous political power. It is during this period that the word "samurai", "those who serve", in a purely military context, is first documented.

The first great test of stability of the system took place in the year 935 with a revolt led by Taira no Masakado, a descendant of Prince Takamochi who had been sent by the imperial authority to quell the disturbances in Kantō and who received the nickname « The Peacemaker". At first the Heian court considered the incident carried out by Masakado to be only a local incident, until he came to proclaim himself "new emperor". Due to the above, a provincial army was sent to quell his rebellion, and he was beheaded in 940. From this moment and due to their social origin, these warrior leaders began to define themselves as a local aristocracy.

Some aristocrats who were unable to obtain high positions in power migrated to the provinces and assumed leadership over the local samurai warriors, notably the Taira clan and the Minamoto clan; In the same way, in the capital the Fujiwara clan had warriors who guarded them and in the Buddhist temples there were armed monks (sōhei) who protected their properties. Minamoto no Yoriyoshi was involved in an important conflict of the time called the Zenkunen War or "war of the first nine years." This conflict lasted from 1051 to 1062, being the first war in the country since the clashes against the emishi. The incident originated when Abe no Yoritoki, a descendant of the emishi and a member of the Abe clan, he did not deliver the collected taxes to the Court, so Yoriyoshi was sent to deal with him. Yoriyoshi and Yoritoki had already reached a peaceful agreement but an internal conflict broke out in the Abe clan and Yoritoki was killed. With this fact, war was declared between Abe no Sadato, son of Yoritoki, and the Minamoto. It was not until 1062 that Yoriyoshi was able to defeat the Abe in the battle of Kuriyagawa, taking the rebel's head to Kyoto as a sign of triumph. Yoriyoshi's son Minamoto no Yoshiie stood by his father's side throughout the conflict, earning great prestige for his military prowess. This earned him the nickname Hachimantarō or "the first-born son of Hachiman, god of war".

While economic decline and insecurity were pitting the Fujiwara, Taira and Minamoto clans at odds both inside and outside the court in the second half of the century XI, the imperial family restored its political power with the accession to the throne of Emperor Go-Sanjō (1068-1073) who left the Fujiwara clan impeded in administrative decisions, regulated the shōen, decided to apply economic reforms to the obsolete ritsuryō and established an institution called insei (cloistered government), where the emperor at the time of abdicating would retire to a Buddhist temple but would retain a regent position over his successor, filling the power vacuum left by the Fujiwara clan due to factional and internal disputes. His successor, Emperor Shirakawa (1073-1087) applied insei to its fullest, ruling as a retired emperor for more than 40 years until 1129, ruling over three puppet emperors. Emperor Toba (1107-1123) also embraced the insei, ruling for more than three decades until his death in 1156 and maintaining his influence over three other emperors. In this period, however, there were disagreements between the reigning and retired emperor, giving way to military power the authority to govern the country over civil authority.

In the year 1083, an armed conflict broke out again in which the Minamoto would be involved, now in the Gosannen War or "war of the last three years", caused by differences between the leaders of the former allied Minamoto clans and Kiyowara. After a fierce three-year battle in which the Court refused to aid the Minamoto, the Minamoto were nevertheless eventually victorious. When Yoshiie went to Kyoto in order to seek a reward, the Court refused and even reproached him for the back taxes that he owed, thus beginning a clear distance between the two. Meanwhile, their rivals, the Taira, enjoyed an increasing relationship with the Imperial Court due to their exploits in the west of the country. The rivalry between the Minamoto and Taira clans was increasing and becoming more and more evident. In 1156, taking advantage of the death of Emperor Toba, a conflict took place between the two clans, when Minamoto no Yoshitomo joined Taira no Kiyomori against his father Minamoto no Tameyoshi and his brother Tametomo, during the Hōgen Rebellion. The battle was very brief and in the end Tameyoshi was executed and Tametomo was punished with banishment. This rebellion also called into question the power of the insei when the retired Emperor Sutoku was defeated by the ruling Emperor Go- Shirakawa, and also sentenced the final fate of the Fujiwara clan that was banished from power, being monopolized exclusively by the Taira and Minamoto clans.

In 1159 there was a new confrontation known as the Heiji Rebellion, where Yoshitomo clashed with Kiyomori. The victory of the Taira clan was so decisive that the members of the Minamoto clan fled to try to save themselves. The Taira gave chase and Yoshimoto was captured and executed. Of the members of the original branch of the Minamoto family, only a few remained, and they were almost completely annihilated. In 1167 Taira no Kiyomori received from the emperor the title of Daijō Daijin (Grand Minister), the which constituted the highest rank that the emperor could grant, so he became the de facto ruler of the country, being the first military ruler in Japanese history. on behalf of Kiyomori, he came into conflict with the retired Emperor Go-Shirakawa who was trying to exert power through the insei from 1158 and around 1177 the emperor planned a coup that failed and he was exiled, suppressing his political power, while Kiyomori named his infant grandson as heir to the throne in 1178, who in 1180 assumed the throne with the name of Emperor Antoku, causing the wrath of opponents of the Taira clan, beginning the Genpei Wars.

Genpei Wars

The Genpei Wars (源平合戦, Genpei kassen, Genpei gassen?) were a series of civil wars led again by the most influential clans on the country's political scene: the Taira and Minamoto. These wars took place between 1180 and 1185. In 1180, two independent rebellions broke out in the country, led by two different generations of the Minamoto clan: in Kyoto by the veteran Minamoto no Yorimasa and in Izu Province by the young Minamoto no Yoritomo. Both revolts were put down relatively easily, on the one hand forcing Yoritomo to escape to Kantō, while Yorimasa was defeated in the battle of Uji, where he committed seppuku before being captured.

After two years of minor skirmishes between the two sides, the Taira decided to confront Minamoto no Yoshinaka, Yoritomo's cousin, in 1183, to prevent Yoritomo from helping him. Yoshinaka defeated the Taira in the battle of Kurikara and directed his army towards where Yoritomo was. The armies of Yoshinaka and Yoritomo finally met at the Battle of Uji in 1184. Yoshinaka lost the battle and tried to flee, but was overtaken at Awazu, where he was beheaded. With this victory, the main branch of the Minamoto would focus its efforts on defeating its main enemies: the Taira.Yoshitsune led the clan's army on behalf of his older brother Yoritomo, who remained in Kamakura. Finally, in the battle of Dan no Ura the Minamoto were victorious. Yoritomo considered that his sister represented a threat and a rival, so his men pursued Yoshitsune until they defeated him during the Battle of Koromogawa in 1189, where the latter committed suicide.

Kamakura Period

In 1192 Minamoto no Yoritomo proclaimed himself shōgun, a title that until then had been temporary and became a high-level military title. With this the shogunate was instituted as a permanent figure, which would last for about 700 years until the Meiji Restoration. With the new figure of the shōgun, the emperor would become a mere spectator of the political and economic situation of the country, while the samurai would become the de facto rulers..

Yoritomo established the coastal town of Kamakura in eastern Japan as the seat of the shogunate, thus this historical period of samurai rule takes its name. The Imperial Court granted Yoritomo the power to appoint his own vassals as provincial protectors (shugo ) and stewards (jitō ), who were charged with administering the private estates.. At the same time, the Imperial Court continued to appoint provincial officials and the owners of private properties appointed the administrators of said lands. Thus, the political structure during the Kamakura period was dual: a civil administration sponsored by the Imperial Court and a feudal administration sponsored by the shogunate.

After only three shoguns of the Minamoto clan and after the death of the last one, the Minamoto clan had no more heirs. Hōjō Masako, Yoritomo's widow, made the decision to raise a one-year-old boy belonging to a branch of the Fujiwara clan and named him shōgun. In this way the Hōjō clan would perpetuate itself in power for several decades, appointing a junior shōgun and dismissing him when he turned twenty, achieving puppet rulers to exercise control of the country. For this reason in 1219 the retired emperor Go-Toba, seeking to reestablish the imperial power that they enjoyed before the establishment of the shogunate, accused the Hōjō of outlaws. Imperial troops mobilized, leading to the Jōkyū War (1219-1221), which would culminate in the Third Battle of Uji. During this, the imperial troops were defeated and Emperor Go-Toba was exiled. With Go-Toba's defeat, the rule of the samurai over the country was confirmed.

After the war, various land disputes arose between vassals, aristocrats and peasants, for which reason the Hōjō clan drafted the Goseibai Shikimoku in 1232, which served as a legal code in the shogunate, and that in turn codified the military customs of the samurai, earning their trust, since it was not based on Confucianism like the codes applied in the Imperial Court and was very precise and concise in terms of penalties, which is why it was effective until the end of the Tokugawa shogunate.

On the literary side, the works reflected the nature of conflict and chaos, such as the Hōjōki, written by Kamo no Chōmei in 1212. In poetry, the poetry compilation waka Shin Kokin Wakashū, presented in 1205. In the religious aspect, there was a popularization of Buddhism, which it took advantage of to offer "salvation" in times of chaos. New forms of Buddhist beliefs were created, easy to understand and which despised the ritual aspect, spreading among the samurai and peasant class. The most important sects that arose were: Jōdo shū founded by the monk Hōnen at the end of the Heian era and which was banned between 1207 and 1211 due to differences with the Imperial Court; the Jōdo Shinshū created by Shinran, a disciple of Hōnen; the Ji shū created by Ippen; the Sōtō and Rinzai schools of Zen Buddhism, founded by Dōgen and Eisai respectively; and Nichiren Buddhism, founded by Nichiren.

Mongol invasions of Japan

After Kublai Khan claimed the title of Emperor of China, he decided to invade Japan with the purpose of bringing it under his rule. This would be the first time that the samurai could face the forces of foreign enemies., the latter did not feel any interest in the traditional Japanese way of making war.

The first invasion took place in 1274, when Mongol troops landed at Hakata (present-day Fukuoka). The sounds of drums, bells and war cries scared the samurai's horses. During this battle the Japanese troops faced a very different technique in the use of the bow than they were used to, since the Mongols shot at long distances and at the same time generated "arrow clouds" as opposed to single shots and close range. distance made by the Japanese archers. Another big difference between the two forms of combat was the use of catapults by the Mongol army. During the night of the day of the battle, a heavy storm inflicted heavy damage on the invading fleet, so they decided to return to Korea to rearm their army. After the withdrawal of the enemy army, the Japanese took a series of preventive measures, such as the construction of walls in the vulnerable points of the coast, as well as the implementation of a guard. Part of the events related to the first invasion attempt are mentioned in the Book of Wonders (1298) by the Venetian merchant Marco Polo where he makes several other references to the island of Cipango. According to Marco Polo, Cipango was a very large island that was in the China Sea, 1,500 miles from the coast and that was inhabited by white and idolatrous indigenous people, who were not under the yoke of any foreign monarch. The incalculable wealth that this territory possessed is highlighted in the book of wonders, since the lord of the island himself had a great palace covered entirely in gold.

The second invasion attempt took place in 1281. The samurai raided the enemy ships from small rafts, which only had the capacity to transport twelve warriors, in an effort to prevent the landing of troops on the coasts. After a week of fighting, an imperial emissary was sent to ask Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun, to intercede for them. A typhoon swept through the Mongol fleet and it sank almost entirely. This fact gave rise to the myth of the Kamikaze (神風, lit. «Divine Wind»?), considered as a sign that Japan was chosen by the gods and, therefore, they would take care of their safety and survival. Survivors decided to withdraw and in this way the country would not face a major invasion again for several centuries.

Kenmu Restoration

In the early 14th century the Hōjō clan, which was in decline, faced an attempt at imperial restoration, now under the figure of Emperor Go-Daigo (1318-1339). When the Hōjō learned of this, they sent an army from Kamakura, but the emperor fled before they arrived, taking the imperial regalia with him. Emperor Go-Daigo sought refuge in Kasagi among warrior monks who welcomed him and left. prepared for a possible attack.

After attempts by the Hōjō to negotiate with Emperor Go-Daigo to get him to abdicate, and given his refusal, they decided to raise another member of the imperial family to the throne. However, because the emperor had taken the royal regalia, they were unable to carry out the ceremony. Kusunoki Masashige, an important warrior who would later serve as a reference and model for future samurai, fought for Emperor Go -Daigo from a yamashiro (mountain castle). Although his army was not very numerous, the orography of the place gave it an extraordinary defense. The castle finally fell in 1332, so Masashige decided to flee to continue the fight. The emperor was captured and taken to the Hōjō headquarters located in Kyoto and would later be exiled to the island of Oki. The Hōjō tried to finish off the army headed by Masashige, who built another castle in Chihaya with even better defenses than the previous one, so the Hōjō were immobilized. Masashige's staunch defense motivated Go-Daigo to return to the scene again in 1333. Upon learning of his return, the Hōjō decided to send one of their top generals after him: Ashikaga Takauji. Ashikaga at that point decided that it would be more beneficial for him and his clan to ally with the emperor's side. For this reason, he decided to launch the attack together with his army towards the Hōjō headquarters in Rokuhara.

The blow received by Ashikaga's treachery had dire consequences for the regents and their army was severely depleted. The final blow would come that same year of 1333, when a warrior named Nitta Yoshisada joined the imperial supporters and increased his forces. Nitta and his army went to Kamakura and defeated the Hōjō.

Muromachi Period

The Muromachi period (室町時代, Muromachi-jidai?) spans the duration of the Ashikaga shogunate (足利幕府, Ashikaga bakufu? ), second military feudal regime, in force from 1336 to 1573. The period owes its name to the Muromachi area of Kyoto, where the third shōgun Yoshimitsu established his residence.

Having helped Emperor Go-Daigo regain the throne, Ashikaga Takauji expected to receive a rich reward for his services. Because he considered that what was offered was not enough and taking advantage of the dissatisfaction of the samurai class with the new government, he decided to rebel.The Ashikaga were descendants of the Minamoto clan, so they could access the imperial throne. For this reason, the emperor decided to act quickly and sent an army against Takauji, following him to Kyūshū. But Takauji was not defeated and returned in 1336. The emperor sent Masashige to face the rebel troops in Minatogawa (now Kobe); the clash proved a decisive victory for Takauji. Faced with this situation, Masashige decided to commit seppuku. At this time the shōgun named his own son (emperor Kōmyō), while Emperor Go-Daigo fled to the town. Yoshino, so for the next fifty years there were two imperial courts: the Southern Court in Yoshino and the Northern Court in Kyoto. This conflict would become known as Nanbokuchō (南北朝, 'Nanbokuchō'? literally “Southern and Northern Courts”). It was not until 1392 and thanks to the diplomatic skills of one of the greatest rulers in Japanese history, the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, that both lineages were reconciled and the Southern Court capitulated.

With the division of the imperial government, all effective political power was lost, since the Northern Court received the patronage of the shogunate and the Southern Court controlled a few territories. The Ashikaga shogunate was established as the central government, but it was very weak, unlike the Kamakura shogunate. The main reason is that Japan's provincial protectors were no longer mere officers, and had already organized local samurai and formed armies based on the concept of lord and vassal, evolving into feudal lords with independent command over various locations. This new class of local warlords was called daimyō (大名, 'daimyō'? lit. «great last names»).

Sengoku Period (1467-1568)

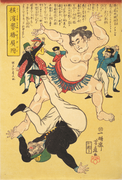

After a brief period of relative stability, a political vacuum was created during the shogunate of Ashikaga Yoshimasa, grandson of the celebrated Ashikaga Yoshimitsu. Yoshimasa used to be totally devoted to artistic and cultural issues, so he completely disregarded the country's economic and political situation. Because of this, opportunistic landowners began an internal struggle for power and land, known as the Ōnin War (応仁の乱, Ōnin no Ran?), and also took for themselves the title of daimyō. This period of history, between 1467 and 1568, is known as the Sengoku period (戦国時代,, Sengoku jidai?) or “warring states period”. It is precisely under this climate of instability and armed conflicts, in which the samurai have their greatest participation.

Among the most important figures of this period are Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin, whose legendary rivalry has inspired several literary works. The armies of Shingen and Kenshin met in the well-known Battles of Kawanakajima (1553-1564). Although some of them were mere skirmishes, the Fourth Battle of Kawanakajima, in 1561, was of great importance in terms of the application of combat tactics, due to the considerable casualties on both sides, due to the hand-to-hand confrontation between the two leaders and due to the close result in which the combat ended.

The war collapsed the order of the old State and the system of private territories; instead, it demonstrated the strength of the peasant and warrior class as they instituted autonomous entities at the local level. Similarly, cities that had been built on key traffic routes in Japan came to be run by armed citizens. The daimyos who managed to incorporate these autonomous localities into their political power, therefore, obtained greater status and power. This dynamic, with the rise of new political and economic centers throughout the country, made the society of the Sengoku period very different from what had existed before, in which power was concentrated exclusively in the capital.

With this infighting raging for more power and land, it was only a matter of time before some powerful daimyō tried to reach Kyoto to seek to overthrow the shōgun, which happened in 1560. Imagawa Yoshimoto marched towards the capital accompanied by a large army for this purpose. However, he did not count on facing the troops of Oda Nobunaga, a secondary daimyō whom he outnumbered twelve to one in number of soldiers. Yoshimoto, confident of his military might, used to celebrate victory even before the battle was over. Oda Nobunaga managed to attack him off guard during one of his famous celebrations at the Battle of Okehazama. When Yoshitomo left his store due to the scandal, he was surprised and killed on the spot. Nobunaga then went from being a minor character to becoming a leading figure on the country's political and military scene.

Cultural flowering and contact with the West

Despite the state of war, many characteristic elements of Japanese culture developed in this period, such as architecture, painting, singing, and poetry. The third shōgun , Yoshimitsu, was a great promoter of the arts and during his reign the Kitayama culture arose that spread during the second half of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th century. In this period the drama nō and kyōgen were born and the shōgun himself ordered the construction of the Kinkaku-ji (金閣寺, Kinkaku-ji? Temple of the Golden Pavilion). Later, in the second half of the century In the 15th century, the eighth shōgun, Yoshimasa, promoted the Higashiyama culture, in which Zen Buddhism and wabi-sabi aesthetics influenced cultural harmonization between the Imperial Court and the samurai class, and the flourishing of artistic expressions such as the Japanese tea ceremony, ikebana, kōdō, and renga >, among others.

During the final stage of the Sengoku period, the first Europeans arrived in Japan. It happened in 1543, when a ship with Portuguese on board was shipwrecked off the coast of the island of Tanegashima (south of Kyushu) and on that ship there were firearms, which would be the first to be introduced to Japan. Later in 1549 the Spanish Jesuit Francisco Javier arrived in Kyushu and began to spread Christianity in Japan. Over the next few years, Portuguese, Dutch, English, and Spanish traders arrived in Japan, as did Jesuit, Franciscan, and Dominican missionaries. The Japanese regarded European visitors as the nanban (南蛮, 'nanban&# 39;? «barbarians from the south») due to arriving in Japan from that direction, while Europeans viewed the Japanese as a complex feudal society, with highly urbanized country and sophisticated pre-industrial technology.

Firearms brought by the Portuguese were the biggest innovation during the period, as firearms began to be produced in many areas of Japan and the use of arquebuses at the Battle of Nagashino in 1575 was a decisive factor. Christianity spread very quickly, especially in the west, and included the conversion of some daimyos. However, the Japanese authorities eventually saw Christianity as a threat that could trigger a possible European conquest of Japan, and so they outlawed it. their practice became violent and progressively severed trade links with the rest of the world (except China and the Netherlands) beginning in the Edo period.

Azuchi-Momoyama Period

In 1573 Nobunaga marched on Kyoto and deposed the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshiaki, marking the beginning of what is known as the Azuchi-Momoyama period (安土桃山時代,, Azuchi Momoyama jidai?), which takes its name from two emblematic castles of the time: Azuchi Castle and Fushimi-Momoyama. Just a week after having achieved the retirement of shōgun Yoshiaki, Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) managed to convince the emperor to make the change of era name for "Tenshō" as a symbol of the establishment of a new political system. The emperor also granted him the title of Udaijin (太政大臣, 'Udaijin' ? lit. "Great Minister of State") , the same one he held for four years until, claiming military duties, he delegated it to his son.

Oda Nobunaga

Nobunaga was born in 1534 in the province of Owari and until 1560 had been a minor daimyō. In 1560 Nobunaga achieved fame and recognition by defeating Imagawa Yoshimoto's large army at the Battle of Okehazama. After helping Yoshiaki reach the shogunate, he launched a campaign to seize control of the central part of the country. In 1570 he defeated the Azai and Asakura clans during the battle of Anegawa and in 1575 he defeated the legendary Takeda clan cavalry during the battle of Nagashino. Other of his main enemies were the warrior monks Ikkō-Ikki , members of the Jōdo-Shinshu sect of Buddhism. With the Ikkō-Ikki Nobunaga maintained a twelve-year rivalry, ten of which he dedicated to the longest siege in Japanese history: that of the Ishiyama Hongan-ji fortress.

In 1576 he built Azuchi castle, which became his base of operations. By 1582 Nobunaga dominated almost the entire central part of Japan, as well as his two main roads: the Tōkaidō and the Nakasendō, so he decided to extend his domain to the west. Two of his top generals were entrusted with this task: Toyotomi Hideyoshi would pacify the southern part of the west coast of the Seto Inland Sea in Honshū, while Mitsuhide Akechi would march up the north coast of the Sea of Japan. During the summer of that same year, Hideyoshi was detained during the siege of Takamatsu Castle, which was controlled by the Mōri clan. Hideyoshi requested reinforcements from Nobunaga, who ordered Mitsuhide to go ahead and join them. Mitsuhide, in the middle of the march, decided to turn back towards Kyoto, where Nobunaga had decided to stay at the Honnōji temple with only his personal guard. Mitsuhide attacked the temple and burned it down in what is known as the "Honnōji Incident", in which Nobunaga died committing seppuku.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598) came from a family of humble origins and his father had been a peasant who had fought in Nobunaga's army as an ashigaru soldier until he was shot by a gun. The arquebus forced him to retreat. Hideyoshi followed in his father's footsteps and, thanks to his prowess on the battlefield, was rapidly promoted several times, eventually becoming one of the leading generals of the Oda clan.

During the "Honnō-ji Incident", Hideyoshi was besieging Takamatsu Castle and quickly received the news of his master's death, so he immediately made a truce with the Mōri clan and returned to Kyoto by forced marches.. The army of the new shōgun Akechi Mitsuhide, who had assumed the title, and that of Hideyoshi met on the banks of the Yodo River, very close to a small town called Yamazaki, from which the confrontation receives its origin. name. Hideyoshi was victorious and Mitsuhide was forced to escape. During his flight, a group of peasants killed him, thus ending his government of only thirteen days.

Having avenged the death of his former master gave him the long-awaited opportunity to become the highest military authority in the country, and for the next two years he faced and defeated rivals who opposed him. In 1585, and after having strengthened control of the center of the country, he began his advance to the west, beyond the limits that Nobunaga had reached. By 1591 Hideyoshi had managed to unify the country, so he decided to conquer China. He requested the assistance of the Korean Joseon dynasty in attacking the Ming dynasty and to be guaranteed safe passage, which the Korean government refused. Korea was then the scene of two major invasions by Japanese troops between 1592 and 1598; the second ended with the death of Hideyoshi, who during all this time remained in Japan.

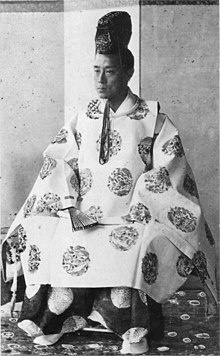

Because Hideyoshi had no royal ancestry nor did he come from any of the historic Japanese clans, he was never bestowed the title of shōgun. Instead, he received a series of lesser titles: Kanpaku (関白, 'Kanpaku'? regent) in 1595, that of Daijō Daijin (太政大臣, 'Daijō Daijin'?) in 1586; finally decided to use the title Taikō (太閤, 'Taikō'? "Kanpaku retired").

Tokugawa Ieyasu

Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616) spent most of his childhood as a hostage to Imagawa Yoshimoto's court, his clan being vassals of the Imagawas. After Oda Nobunaga's victory over Yoshimoto, many of the daimyō defected, either becoming independent or allied with the Oda clan, the most notable of the latter being Ieyasu himself.

Under Nobunaga's command, Ieyasu fought in 1564 against the Ikkō-ikki of Mikawa Province and in 1570 fought at the Battle of Anegawa alongside Nobunaga's forces. In 1572 he had to face one of the greatest military challenges of his life: the battle of Mikatagahara, where his army was defeated by Takeda Shingen's cavalry, who would die the following year from a shot from an arquebus. In 1575 he was present at the Battle of Nagashino where the Takeda clan was defeated and from that moment he dedicated himself to consolidating his military position, even after Toyotomi Hideyoshi took control of the country.

Because Ieyasu's fiefdom was in the center of the country, he avoided attending the pacification campaigns in Shikoku and Kyūshū, although he did face the Hōjō clan in late 1590, during the siege of Odawara. Thanks to After the victory against the Hōjō, Hideyoshi gave him the confiscated lands, so he moved his capital to Edo (today Tokyo). His new location in Kyūshū also allowed him to evade the responsibility of fighting during the Japanese invasions of Korea, a war that it significantly weakened the armies of its main rivals.

Battle of Sekigahara

After Hideyoshi's death, Tokugawa Ieyasu began to establish a series of alliances with powerful figures in the country through arranged marriages, making Ishida Mitsunari, one of the five bugyō (奉行, 'bugyō'? magistrate), began to gather all those who opposed Ieyasu.

On August 22, 1599, while Ieyasu was organizing his army with the intention of confronting a rebel daimyō named Uesugi Kagekatsu, Mitsunari decided to act with the support of the other bugyō > and three of the four tairō (大老, 'tairō' ? lit. «Great old man»), who sent a formal complaint against Ieyasu, accusing him of thirteen different charges. The charges included having married sons and daughters for political purposes and having taken possession of Osaka Castle, Hideyoshi's former residence, as his own. Ieyasu interpreted the letter as a clear declaration of war, so that virtually all the daimyō of the country They enlisted in either Mitsunari's "Western Army" or Ieyasu's "Eastern Army".

The two armies met in what is known as the Battle of Sekigahara (関ヶ原の戦い , Sekigahara no tatakai ?), which took place on October 21 (September 15 in the old Chinese calendar) in the year 1600 in Sekigahara (now Gifu Prefecture). battle, Ieyasu was victorious after several generals of the "Eastern Army" decided to switch sides in the course of the conflict. Ishida Mitsunari was forced to flee, although he was later captured and beheaded in Kyoto. Thanks to this victory, Ieyasu became the country's top military and political figure.

Edo Period

Biombo by Kyosai Kiyomitsu (1847).

The Edo period (江戸時代, Edo jidai?) , also known as the Tokugawa period (徳川時代, Tokugawa jidai?), is a division of Japanese history, spanning from 1603 to 1868. The period delimits the Tokugawa shogunate or, by its original Japanese name, Edo bakufu (江戸幕府, Edo bakufu?), which was the third and last shogunate to hold power in Japan.

In 1603, Ieyasu was officially appointed by Emperor Go-Yōzei as shōgun, a position he would occupy for only two years, since in 1605 he decided to abdicate in favor of his son Hidetada, taking for himself the title of Ōgosho (大御所, 'Ōgosho' ? "cloistered shōgun"). As ōgosho maintained the government control. He also had to face the threat of Toyotomi Hideyori, Hideyoshi's son, since some supporters claimed that he was the legitimate successor of the government and many samurai and rōnin allied with him in order to fight the shogunate., which led to two battles summarized as the "siege of Osaka". In 1614, the Tokugawa, under the leadership of Ōgosho Ieyasu and shōgun Hidetada, led a large army at Osaka Castle in what became known as "The Winter Siege of Osaka". Osaka". Eventually, Ieyasu made a deal with Hideyori's mother, Yodogimi, and Tokugawa troops began filling the moat with sand, so Ieyasu returned to Sunpu. After Hideyori again refused to leave the castle, the latter was besieged, in what is known as the "Summer Siege of Osaka". Finally, in late 1615, the castle fell during the Battle of Tennōji, where the defenders were killed, including Hideyori, who decided to commit seppuku. With the Toyotomi exterminated, there were no longer any serious threats to Tokugawa domination of Japan.

With the unification that occurred in the Azuchi-Momoyama period, Japan had become a more peaceful country, and in the Edo period the social structure that had been established after Hideyoshi's unification was consolidated, with three ranks: the class samurai ruler, the agricultural and the citizen (artisans, merchants and merchants). The pacification and the increase in the production of gold and silver since the Azuchi-Momoyama period, gave more stable living conditions in the social classes for more than two and a half centuries, unlike previous periods, and this brought as a consequence that the The population developed their vocational skills. The samurai class organized itself and developed an efficient and legal administrative system, as well as advances in various fields of scholarship, while farmers and citizens improved in the material realm. By the 17th century rice production had doubled and the cultivation of valuable crops for the market spread to all villages. With industrial development, a level of prosperity was reached in many cities and the economic power of the merchants surpassed that of the samurai.

Sakoku

When Ieyasu came to power, Japan was still in the heyday of the Nanban trading period, and while trading with Europeans was still allowed as with Hideyoshi, his actions were viewed with suspicion. In 1614 the first transoceanic voyage to the West was made by the galleon San Juan Bautista, with a Japanese embassy headed by Hasekura Tsunenaga. Between 1604 and 1636, the shogunate had also allowed the use of 350 shuinsen, merchant ships that traded in various regions of Asia.

Nevertheless, the constant expansion of Christianity was considered by the shogunate as a "problem", especially with the advantages that the Christian daimyos of Kyūshū had and their relationship with European traders, and the perception that the presence of Spanish and Portuguese in Japan would unleash a process of conquest similar to that which occurred in the New World, especially the conquest of the Philippines by the Spanish. The shogunate thought that the activity of European missionaries was a facade for political conquest. In 1612 vassals and residents of Tokugawa clan estates were forced to abandon Christianity, in 1616 trade was restricted Outside the cities of Hirado and Nagasaki, in 1622 120 missionaries and converts were executed, in 1624 the Spanish were expelled from Japan, and in 1629 thousands more converts were executed.

During the rule of the third Tokugawa shōgun, Iemitsu, the first great famine of the Tokugawa shogunate occurred, which lasted from 1630 to 1640-1641, leading to peasant protests in 1632, 1633 and 1635. The Shimabara Rebellion of 1637-1638 was the most dramatic consequence of the deteriorated relationship with the government due to this crisis, in which Catholic peasants faced off against the large government army. had neither religious nor political purposes, this event apparently convinced Iemitsu to definitively restrict Christianity in Japan, for which reason he issued an order in 1639 prohibiting said religion, as well as preventing Portuguese priests from entering the country and the departure of Japanese on pain of death, as well as the exclusion of Japan to the world. During this period of isolation, known as sakoku (鎖国 , 'sakoku'?), commercial relations with all European nations ceased, except for the Netherlands, with whom trade continued but was authorized exclusively on Dejima. Japan continued to maintain trade relations with China and Korea, albeit to a limited extent.

Society and politics

With the Tokugawa shogunate, a balanced power structure was established, known as bakuhan (the shogunate and the fiefs), in which the shogunate directly governed the city of Edo, the seat of government military, while daimyos ruled in their fiefdoms. After the pacification, many samurai lost their possessions and lands, as only a few daimyos existed (about 260 c. XVIII), so they had few options: lay down their swords and become peasants, be vassals of the daimyō, or be vassals of the shōgun (become hatamoto). Daimyos were also strictly controlled, as the shogunate imposed the policy of sankin kōtai on them from 1635 to 1862, in which the daimyō's family was forced to live in the city of Edo, while the daimyō had to alternate his residence annually between Edo and his fiefdom, which caused added expenses by having to maintain two residences and pay for large processions, limited his economic and military power and thus avoiding any attempt at rebellion against the shogunate.

Apart from the members of the bakuhan, the emperor and courtiers (kuge) also enjoyed a privileged position. Below them were the "four social classes" (身分制, mibunsei?) in which the population was divided: the samurai at the top (about 5% of the population), then the peasants (about 80%), followed by the artisans and, lastly, the merchants. Peasants had to live in the fields, while samurai, artisans, and merchants lived in the cities that formed around the daimyō's castle and were subservient to his fiefdom. Apart from this system, there were the eta and the hinin, the most disadvantaged categories, who were considered from outcasts to "non-humans".

Culture

Japan timidly received the Western techniques and sciences of rangaku (蘭学, ' rangaku'? «dutch learning») through of books and supplies carried by Dutch traders on Dejima. The fields of study ranged from medicine, geography, astronomy, art, natural sciences, languages, physics and mechanics. During the government of the shōgun Tokugawa Yoshimune, the introduction of foreign books was made more flexible in 1720 and their translation into Japanese was allowed, which caused a greater boom in this study. At the beginning of the 19th century there was a clear cultural exchange between the Japanese and the Dutch. For example, Dr. Philipp Franz von Siebold first taught Western medicine in 1824 to Japanese students, with the permission of the shogunate. However, the shogunate decided to reverse its support for rangaku in 1839 by enacting the edict bansha no goku, which provoked the repression of several scholars who questioned the effects of the sakoku and the edict of repulsion of foreign ships of 1825. However, these edicts ceased to be valid. take effect in 1842 and rangaku was again taught, until it became obsolete with the abolition of sakoku a decade later.

Locally, Neo-Confucianism became the main intellectual movement and permeated the shogunate, appealing to greater attention to the secular life of man and society, resulting in a rationalist and humanist thought. By the middle of the 17th century it had become mainstream philosophical and laid the foundation for the kokugaku school. i> (国学, 'kokugaku'? «national learning») that rejected Chinese Confucianism and valued pre-Chinese influenced Japanese culture.

With the spread of Neo-Confucianism, the samurai class showed a greater interest in Japanese history and the cultivation of the arts, resulting in the bushido (way of the warrior). There was also a cultural flowering in the popular class, through the chōnindō, and education, literacy and the teaching of arithmetic were extended in a general way to the population.

One of the consequences of this more cultured lifestyle was the appearance of the ukiyo (浮世, 'ukiyo'? «floating world»), which was the fun and entertaining lifestyle of the middle class and which produced a cultural flowering in the Genroku era (1688-1704, also called Genroku culture): the bunraku, the kabuki, geishas, the tea ceremony, music, poetry and literature became part of that world and was exposed as art through ukiyo-e. The ukiyo-e began at the end of the XVII century by Harunobu, and had as its main exponents Kiyonaga and Utamaro in the 18th century and Hiroshige and Hokusai in the first half of the XIX.

Major exponents of literature from this period include the playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon and the poet Matsuo Bashō, who wrote haiku verse during his tour of various sites in Japan at the turn of the century XVII.

Beginning of decline

By the 18th century, freight traffic experienced significant growth in both urban and rural areas. This brought as a consequence that both the shogunate and the daimyos found themselves at the point where the tax revenues that were based on rice production were becoming insufficient to cover the expenses that increased each year. It was decided to increase taxes, but this caused rebellions on the part of the peasant class, added to the appearance of numerous famines and natural disasters that plagued the country, such as the great Meireki fire of 1657, the Genroku earthquake of 1703 and the eruption of Mount Fuji in 1707, which caused thousands of deaths. For this reason, the shogunate carried out several reforms in order to contain a decline in the governance of the country: the Kyōhō reforms (1717-1744) aimed at the financial solvency of the government, the Kansei reforms (1787-1793) resolved several social problems caused by the great famine of Tenmei, which occurred between 1782 and 1788, and in reversing some government decisions, the Tenpō reforms (1830-1842) aimed to control In the social chaos caused by the Great Tenpō Famine, immigration to Edo, rangaku, and the formation of societies were prohibited, although the scope of these reforms extended to the military level. ar, religious, financial and agricultural; and finally the Keiō reforms (1866-1867), which were intended to contain the growing rebellion that existed in the domains of Satsuma and Chöshü, without any success.

Although the government tried to contain the problems, they became more notorious and a desire for greater transformations arose in the popular sector in the face of the inaction of the shogunate. One of these cases was that of the samurai Ōshio Heihachirō, a A minor official of the shogunate in Osaka who, during the great Tenpō famine, begged his superiors to feed the famine victims. Faced with their refusal, Heihachirō sold his books in order to help people, and later, following Neo-Confucian precepts, he accused the shogunate of corruption. He created an army out of peasants, Neo-Confucian students, and other commoners and sparked a rebellion in 1837 that destroyed part of the city before government troops could put it down. Heihachirō committed seppuku when he was captured.

In parallel with what was happening at home, some foreign countries began to put pressure on the shogunate to abandon the sakoku. At the end of the century XVIII several Russian explorers came to the Kuril Islands and Hokkaido (Pavel Lebedev-Lastochkin in 1778 and Adam Laxman in 1792) with the aim of eventually opening trade with Japan, task that was unsuccessfully assigned by Nikolai Rezanov in 1804, thus the Russian Empire clashed with the shogunate over the Sakhalin and Kuril Islands dispute in the first half of the century XIX.

In 1808, the British frigate HMS Phaeton arrived in the port of Nagasaki, challenging the Dejima and shogunate authorities by forcibly demanding supplies under the threat of firing their cannons at the Japanese and Chinese ships anchored in the port. The Nagasaki bugyō (official of the shogunate of the city), Matsudaira Yashuide, initially asked for reinforcements but due to their delay, he finally agreed to the demands of the English. After the incident, Yasuhide committed seppuku and alerted the shogunate authorities to the presence of foreign ships, encouraging the "edict of repulsion of foreign ships" created in 1825.

The Morrison incident of 1837, where an American merchant ship returning Japanese shipwrecked was shelled, along with the defeat of the Chinese Empire in the Opium War in 1842 and signaling a turnaround in the international situation in the Far East, led to criticism of the shogunate over its isolation policy, resulting in the abolition in 1842 of the edict of repulsion of foreign ships, the suspension of the executions of foreigners who arrived in the country and in providing supplies to their ships. This is how whalers from England, the United States and other countries came to the coast of Japan to ask for water and food. Despite the fact that this abolition was not for commercial purposes, some countries insisted on the opening of the country: in 1846 the American commander James Biddle, who signed the first treaty between the United States and China, tried unsuccessfully to open trade with Japan, but in 1848 Captain James Glynn achieved the first successful negotiation with the shogunate and was the person he recommended to the United States Congress United negotiations with Japan, if possible, by force, being one of the causes of Commodore Perry's expedition in 1853.

Bakumatsu and Meiji Restoration

Although the political system established by Ieyasu and fine-tuned by his two successors Hidetada and Tokugawa Iemitsu remained largely intact until the mid-19th century, various political, social, and economic changes rendered the Tokugawa government inefficient and subsequently caused its collapse. In the mid-18th century, the shogunate and daimyos suffered serious economic difficulties as wealth shifted to the merchant society in urban areas. The growing discontent among the farmers and samurai motivated the Government to try to counteract the situation through various measures, none of which had any effect. In addition to internal problems, the country's situation also worsened due to various pressures from foreign powers that tried to force the Government to open the country to trade. This period would be known between 1853 and 1867 as bakumatsu (幕末, 'bakumatsu&# 39;?).

Opening to Western Powers

In July 1853 American Commodore Matthew Perry arrived in Tokyo Bay with a fleet of ships known by the Japanese as the "Black Ships" (黒船, kurofune ?) and gave Japan a deadline to break isolation in one year, threatening that if they his request Edo would be besieged by the sophisticated Paixhans guns of the ships. Despite the fact that the Japanese began to fortify themselves before the return of the Americans (the islands-fortresses of Odaiba were created, the ship was built Shōhei Maru from rangaku texts and a reverberatory furnace was built to make cannons), when Perry's fleet returned in 1854, they were met without any resistance by the shogunate officer, A be Masahiro, who had no experience in national security and unable to reach a consensus between the various factions (Imperial Court, shogunate and daimyos) decided unilaterally to accept Perry's demands and allow the opening of several ports and the posting of an American ambassador. in Japan, with the signing of the Kanagawa Convention of March 1854, formally terminating the sakoku policy that governed Japan for more than two centuries. Although the shogunate was initially undecided about how to deal with foreign powers, trade was eventually allowed and a series of treaties, known as "Uneven Treaties" (Anglo-Japanese Friendship Treaty, Harris Treaty, Friendship Treaty) were signed. and Anglo-Japanese Trade), during the Kanagawa Convention, without the consent of the imperial household, which led to strong anti-Tokugawa sentiment.

Abe's decision significantly injured the stability of the shogunate, although he tried to seek military assistance from the Netherlands and sought advice from the shinpan and tozama daimyō, a fact that annoyed the fudai daimyō who held the highest positions. For all this he was replaced by Hotta Masayoshi. However, some officials such as Tokugawa Nariaki, a follower of the Mito school, created from Neo-Confucianism and kokugaku, expressed feelings against the foreign presence and appealed for reverence for the emperor, since they considered that the Tokugawa shogunate it was no longer a trustworthy institution. This nationalist thought was known by the motto sonnō jōi (尊王攘夷, 'sonnō jōi'? «revere the emperor, expel the barbarians»), proposed by the thinker of the Mito Aizawa Seishisai school in a book published in 1825.