History of italy

The history of Italy is closely linked to that of Western culture and the history of Europe. Many important historical events in the Western world, as well as several of the achievements that have conditioned universal culture, have taken place in the country or have been carried out by its peoples.

Heir to multiple ancient cultures, such as the Etruscans and the Latins, recipient of the Greek colonization and home of Magna Graecia, it was the cradle of Roman civilization and saw the birth of the Republic and the Roman Empire, bequeather of great part of Western culture and one of the largest in history, of which Italy was the absolute center, both political and economic and cultural, in the course of classical Antiquity.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Italy suffered a series of Germanic invasions, alternated with Byzantine and Frankish attempts to rebuild the unity of the Roman Empire. Rome, seat of the papacy and source of imperial legitimacy, was in those times a focus that attracted figures such as Justinian I and Charlemagne.

During the Middle Ages, Italy would become a mosaic of states and city-states (called liberi comuni) often fighting each other for hegemony over the rest, with frequent interventions by surrounding powers and the Holy Headquarters that, through the figure of the pope as sovereign, governed a good part of central Italy in the territory known as the Papal States, with its capital in Rome.

Italy's privileged geographical situation made it key in continental trade and favored the flourishing of rich maritime republics connected with European history and the entire Mediterranean Sea. The struggle between the imperial temporal power, which included Italy, and the papal spiritual power, which had its seat in Rome, had special political repercussions in Italy.

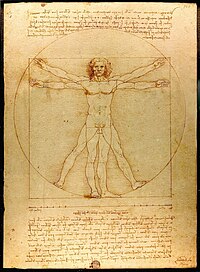

This legacy of political relevance made it the focus of struggles for power on the European continent. In addition, the classical and ecclesiastical cultural legacy was the breeding ground for new trends. In the 15th and 16th centuries Italy became the cultural center of Europe, giving rise to Humanism and the Renaissance, and was one of the fields in which the European supremacy of the Spanish Empire was decided with the victory over Francis I of France.

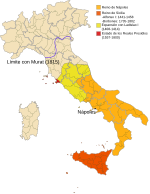

After the decline of the Spanish Monarchy, the Austrian Habsburgs came to control the region, as well as a large part of Central Europe. Transformed into a battlefield during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleon Bonaparte's First Empire, it would go on to fight for its independence. Between 1848 and 1870 the Unification of Italy took place, after a series of wars that involved confronting both the Austrian Empire and papal sovereignty over the Papal States and, from which, Italy was established as a single kingdom politically unified under the royal Savoy dynasty.

Later, the Kingdom of Italy, together with the other European powers, would carry out imperialist policies that would make up the Italian Empire and that led it to participate in the First World War on the side of the Entente, to develop the fascism of Benito Mussolini, to the invasion of Albania and Abyssinia, and to participate in World War II with the Axis Powers together with Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan. After the defeat in World War II, the monarchy would be overthrown and the current republic was established, which had an excellent recovery, placing Italy among the largest developed economies and among the most industrialized countries in the world.

Italy currently belongs to major international organizations such as the G-4, G-7 and G-20, as well as the European Union, NATO, the Quint and the OECD.

Definition of Italy

The name Italy has been in use since ancient times, at least since the 8th century BC. C., initially to designate the southern and central regions of what is known as the Italic peninsula, referring to the Italic peoples, speakers of the languages also called. The etymology of the name is uncertain: Pallottino defends that it derives from the demonym of one of the native Italic peoples of the Calabria region, the (v)itàlii, which mutually share their name with their sacred animal: the calf (viteliú in the Oscan language, vitulus in Latin and vitello in Italian); and that it was used by the ancient Greeks as a general term to designate the inhabitants of the entire peninsula.

The term settled definitively when, the italic city of Rome, from the V century a. C., gradually unified the entire peninsula conquering and federating the rest of the peninsular Italic peoples, beginning with the Latins, of which it constituted a village, and ending with the Etruscans to the north and the Brutians to the south, thus unifying all the peninsular territory under a single regime, that of the Roman Republic, and giving it the name of Italy, which, since then, will constitute the metropolitan territory of Rome itself.

The name Italia was also used on coins minted by the coalition of Italic allies (socii) dissatisfied with not having yet received Roman citizenship, despite the fundamental contribution offered for the conquest of the provinces (at the time Roman citizenship had been granted to many cities within Italy, but not yet to all, and it was still totally non-existent in the territories outside of Italy, which were the provinces), that he declared himself independent; that is to say, the coalition of dissatisfied Italic partners, made up of inhabitants of Samnite, Picean, Apulian and Sabine cities, among others, rose up against Rome and the other Italic centers already provided with citizenship, in the I a. C., and moved the capital of Italy, from Rome to Corfinium (today Corfinio), renamed Itálica, with the intention of erecting the Senate in it and minting coins, which were printed with the writing Italy, and thus marking the beginning of the Social War (war of the allies), that is, the war between Rome and the other Italic cities already provided with Roman citizenship against their Italian allies without citizenship, to which ended in the year 89 a. C. and with the achievement of the Lex Plautia Papiria, which granted full Roman citizenship to all the inhabitants of peninsular Italy; thus further emphasizing the differentiation of status between Italy (and a metropolitan territory of Rome exempt from provincial taxes and, after the aforementioned Social War, inhabited entirely by full-fledged Roman citizens) and the provinces (the remaining territories outside of Italy).

Towards the end of the republican era, in the year 42 a. C., to the territory of Italy were added, de iure, also the lands located to the north of the Rubicon River, thus taking the metropolitan territory of Rome and the name of Italy to the foot of the Alps, and encompassing within Italy what until then had been a province (unlike mainland Italy, which was never a province) known by the name Gallia Cisalpina (corresponding to north of Italy) which, seven years earlier, in 49 a. C., by the will of Julius Caesar and through the Lex Roscia, had received the Plenum Ius, that is, full Roman citizenship for all its inhabitants (who, differently from the other provinces, they already enjoyed comprehensively, for almost a century, the Ius Latii, that is, the Latin citizenship). From then on, Italy remained in its entirety as the central unit of the Empire and continued to be administered in a totally different way from the provincial territories, as a natural evolution of the same Ager Romanus and political, economic and political heart. culture of the Roman Empire.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the word Italy, in addition to referring to the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy and the Byzantine Exarchate of Italy, continued, over the centuries, to designate all the states, kingdoms and republics that inhabited the ancient territory of Roman Italy and that shared a certain cultural, historical, and linguistic affinity, as well as a geographical one, especially emphasizing the same set of Latin dialects, the Italo-Romance languages (and the subgroup of Gallo-Italic languages), which would give origin to the Italian language; while, always in the High Middle Ages, the old adjective of Italic became Italian, leaving the former as a reference for all the inhabitants of Roman and pre-Roman Italy, speakers of ancient Italic languages (such as Latin), and the second as a reference for all the inhabitants of Italy who speak contemporary Neo-Latin languages (such as Italian), that is, from medieval times onwards. Centuries later, romantic nationalism, as it happened in many other parts of Europe (as, for example, in Germany or Greece), based on this cultural, geographical, historical and linguistic unity, its search for a political and state unity, that would lead to the modern Italian state.

Some territories that under the same standards could be called Italian, for different historical reasons, did not become a political part of the modern Italian state, as is the case of regions bordering Slovenia and Croatia (for example, the Istrian peninsula, see Adriatic Question and foibe), with Switzerland (Italian Switzerland: Ticino and the Italian-speaking part of Grisons) and with France (Nice and its surroundings and the island of Corsica), as well as Monaco, Malta and the microstate of San Marino, which constitutes an enclave within the Italian State.

A separate case, unique in the world and much more sui generis, is the result of the pact between the then Kingdom of Italy and the Holy See (known as the Lateran Pacts), where, in 1929, the Holy See political sovereignty over a tiny part of the city of Rome, which constitutes the so-called Vatican State, so that the pope, as bishop of Rome and, at the same time, spiritual head of all Catholics, could exercise his power temporary over a physical territory without politically depending on any State, and thus obtaining a nationalized religious entity within the city of Rome.

Early cultures and the Iron Age

First settlers

The population of the Italian territory rises during prehistory, period from which many important archaeological testimonies have been found. Italy has been inhabited at least since the Paleolithic. Several archaeological sites from this period, and among the most important in the world, are located in Italy.

The site of Monte Poggiolo, dating from the Paleolithic, and Isernia-La Pineta, are some of the oldest sites where man used fire (perhaps the oldest at all). In the Addaura Caves there are vast and rich complexes of engravings, dating between the Upper Paleolithic and the Mesolithic, engravings unique to the world of men and animals. When man settles down and goes from hunter to shepherd and farmer, he leaves in Italy one of the most important traces of all prehistory, constituting the largest set of petroglyphs in the world, over a duration of 8000 years, known as Rock Art of Val Camonica.

The earliest more or less studied cultures in what is now Italy include the Ligurians, an enigmatic people who inhabited northwestern Italy. During the Cardial-Printed Ceramic Culture they created the first societies in Italy, with highly advanced knowledge of agriculture and navigation. Relatively little is known about these peoples, presupposing them to be pre-Indo-Europeans and thus antecedents to the Indo-Europeans, who were soon assimilated by subsequent cultures.

Early civilizations

Similarly, in the south (mainly Sicily), the first adventurers include, after Cyclopean legends, Alymos, Sicans and Sicels as inhabitants of those lands. Without much information about them, it is speculated that they were or were not Indo-Europeans. In Sardinia, a people developed with great knowledge of metallurgy and famous for their megalithic constructions, the nuraghes, whose main deposit is located in Su Nuraxi.

The phonological similarities lead some scholars to associate some of these cultures with the Sea Peoples: the Shirdana with Sardinia, the Shekelesh with Sicily, and the Teresh with the Tyrrhenians, based solely on etymological similarities. Archaeological evidence only supports a certain boom in ceramics of Mycenaean origin throughout the Mediterranean, in the midst of a cultural change, different depending on the site. It is possible that some of the Sea Peoples operated from or moved around the Italian coasts.

Arrival of Indo-European peoples

With the Iron Age, Indo-European peoples arrived in Italy, mainly in four great migrations from the north.

A first wave of migration, probably Indo-European, occurred around the III millennium BC. C. The stelae or menhir-type statuary are characteristic of this period, which frequently had engraved solar signs, apparently distinctive Indo-European signs. A second wave between the end of the III millennium and the beginning of the II millennium BCE C. led to the spread of populations associated with the Beaker and Bronze culture in the Padana plain, in Etruria, and in the coastal areas of Sardinia and Sicily. Around the middle of the II millennium BCE. C., a third wave, known as the Terramaras culture, brings together Italic peoples of the Latino-Faliscan group, who spread the use of iron and the cremation of the dead.

Towards the end of the II millennium and the first half of the I millennium BCE C., there is the fourth and main wave associated with the Culture of the urn fields, it is that of the Osco-Umbrian peoples (belonging to the same Italic group as the Latino-Faliscans), as well as Lepontians and Venetians. They are contemporaneous with the flourishing of the pre-Indo-European Villanovan culture, named after one of its main archaeological sites. It is also known that they cremated and cremated their dead, their necropolis being characterized by typical conical-shaped urns. They spoke the Italic languages, of Indo-European origin. They settled mainly to the north, next to the Po, in Emilia, and in the center of the peninsula (Umbria, Lazio and Abruzzo). Further south, although burial was the general practice, burials of this culture have also been found from Capua, in Campania, to Calabria.

From these cultures come most of the peoples who would inhabit the center, north and south of Italy in a hegemonic way since then. The Latins, whose main city was Alba Longa, would eventually give way to Rome. The Sabines, who gave the region its name Sabinia, lived nearby, in nearby cities such as Reate (Rieti), Interocrea (Antrodoco), Falacrinum (Cittareale), Foruli (Civitatomassa), Amiternum and Nursia (Norcia). The Osci, who include the Samnites, settled in Campania and the rest of southern Italy, as well as the Lucanians, among others. The Umbrians give their name to Umbria and lived in central Italy, in cities such as Perugia, Interamna Nahars (Terni), Fano, Osimo, Fermo and San Severino Marche, among others.

The Etruscans

The Etruscans were a pre-Indo-European-speaking people whose historical center was Tuscany, to which they gave their name (they were called Τυρσηνοί (tyrsenoi) or Τυρρηνοί (tyrrhenoi) by the Greeks and tuscii and then etruscii by the Romans; they called themselves rasena or rašna).

For a long time the origins of the Etruscans were believed to be unknown, due to which three theories arose that tried to explain this problem:

- The Orientalist theory, proposed by Herodoto, which believes that the Etruscans came from Lidia to the centuryXIIIa. C. To demonstrate it is based on the supposed oriental characteristics of his religion and customs, as well as on the fact that it was a very original and evolved civilization, compared to its neighbours.

- The indigenous theory, proposed by Dionisio de Halicarnaso, which regarded the Etruscans as the origins of the Italian peninsula. To argue, this theory explains that there is no indication that Etruscan civilization has been developed elsewhere and that the linguistic stratum is Mediterranean and not Eastern.

- Theory of a “Nordic” origin, defended by many at the end of the centuryXIX and first half XX.It was based only on the similarity of its self-determination (rasena) with the denomination that the Romans gave to certain Celtic villages that inhabited the north of the Alps, in what is currently the East of Switzerland and West of Austria: the ræthii or rhetic, such origin supposed only in parophonies is already discarded.

However, modern research on the origin of the Etruscans, carried out by a group of geneticists and coordinated by Guido Barbujani, a member of the Department of Biology and Evolution at the University of Ferrara (Italy), came to the conclusion that, genetically, the origin of the Etruscans corresponds to the second theory, that is, that of Dionysius of Halicarnassus, thus confirming the autochthonous origin of this people from the Italian peninsula.

From Tuscany they spread to the south, towards Lazio and the northern part of Campania, where they clashed with the Greek polis of Magna Graecia (southern Italy); towards the north of the Italian peninsula they occupied the zone around the valley of the river Po, until the south of the current region of Lombardy. They became a great naval power in the Western Mediterranean, which allowed them to establish factories in Sardinia and Corsica. However, around the V century B.C. C. its power began to deteriorate strongly, to a large extent by having to face, almost at the same time, the invasions of the Celts, from the north, and the competition of the Carthaginians for maritime commerce, from the south.

Their definitive defeat, by the Romans, was facilitated by such confrontations and by the fact that the rasena (or Etruscans) never formed a solidly unified State, but a kind of weak Confederation of medium-sized cities. Some of its main cities were: Veii, Chiusi, Tarquinia, Caere, Valathri, Felsina (Bologna), Aritim (Arezzo), Volsinios (Orvieto) and Vetulonia, among others.

From the IV century B.C. C., Etruria (name of the territory of the Etruscans), was gradually conquered and absorbed by the Roman Republic and, the Etruscans, like the other Italics, federated by the Romans, thus becoming an integral part of Roman Italy.

In a certain way predecessors of Rome and heirs of the Hellenic world, their culture (they were outstanding goldsmiths, as well as innovative shipbuilders) and superior military techniques, made this people the masters of the north and center of the Italian peninsula, from the 8th century b.c. C. until the arrival of Rome. Etruscan art, influenced by the Greek, would mark later Roman art. They are exponents of the same: the Apollo of Veii, the Mars of Todi, the Chimera of Arezzo or the Pediment of Talamone, among others. His influence reached such a point that the first kings of Rome were Etruscans.

Celts and Illyrians

From the XII century BC. C. developed, in Central Europe, the cultures of Hallstatt and its successor of La Tène, from which the Celtic peoples that spread throughout a good part of Europe derive. Their southward expansion led them to settle in northwestern Italy, in the area between the Alps and the plain north of the Po River, with constant pressure to the south of the peninsula, facing the Italic peoples.

The bullfighters settled in the area of what is now Turin, which was its capital. One of the branches of the great tribe of the Boyos reached what is now Bologna, whose place name is of Celtic root, accompanied by Lingones and Senones (which give Senigallia its name). The Padana Plain and the northern part of the current Marches region would be called Ager Gallicus for this reason. Other tribes include the Insubrians, who settled in the western part of Lombardy, and the Cenomani, who settled in the eastern part of the same region. In many cases an assimilation or amalgamation took place between the Celts and the pre-existing Ligurian peoples, thus giving life to a Celto-Ligurian culture.

Similarly, the Illyrians, pushed by the previous ones, found themselves displaced to the south, populating some areas of Veneto (whose name comes from the Italic people of the Veneti), Istria (by the Istrians) and the southern coasts of the Adriatic sea. Some defend that the Messapians, who occupied Apulia, are of Illyrian origin, although others give them a Hellenic or Illyricized Italic origin.

Magna Graecia

Since the 8th century B.C. C. the southern part of the Italian peninsula received a strong Greek influence. Discontent with the ruling class, population growth, lack of land, and the desire to create new trading factories led the ancient Greeks to create numerous colonies abroad. Its proximity, as well as its relative little resistance to this phenomenon, made southern Italy one of the main areas of Greek settlement.

Several of the main Greek polis (cities) were located between the arc formed by the Gulf of Taranto (where Greek cities such as Taras, Síbari, Metaponto, Kalipolis, etc. stood out) and the Gulf of Naples (where there were Greek colonies such as Parténope, Pitecusas, Cumae, Poseidonia, etc.), in the eastern part of Sicily and, to a lesser extent, in certain areas of the Adriatic coast. The group of these powerful Greek polis of southern Italy was known as Magna Graecia (Greater Greece) and its peninsular inhabitants were known as italiotes (that is, southern Greeks). of Italy or Italics of Greek language and culture and, in the same way, the inhabitants of the Greek polis of Sicily were known as Sicilians).

The Euboeans and Rhodians founded Cumae, Reggio Calabria, Naples, Giardini-Naxos and Messina; the Corinthians Syracuse (which in turn would be a focus for further colonies in Italy, such as Ancona); the Megarians, Lentini; the Parthenians-Spartans, Taranto; the Phocians, Elea and the Achaeans Síbari, Metaponto, Turios, Caulonia and Crotona, among others. Meanwhile, Heraclea of Lucania and Locri Epicefiris were slightly later.

This colonization marked the first contact of the Italic peoples with classical Greek culture. The colonies were not mere commercial enclaves, but were also landmarks of the nascent Hellenic civilization: Pythagoras lived in Crotona, Archimedes and Theocritus were natives of Syracuse, Parmenides was a native of Elea... Not surprisingly, the Greeks knew the region like Magna Graecia. They were also the first democracies in Italy. The contrast with the local populations favored in many cases an acculturation of the Italics close to the colonies.

Greek colonization reached its limits in the island territories surrounding the peninsula. In the case of Sicily, the Greeks settled in the northern area, near the Strait of Messina, and on the eastern coast, where cities such as Syracuse played an important role in the Greek world. It collided there, however, with Carthaginian imperialism. The Sicilian Wars between the Greeks and the Punics did not have a winner, although the island ended up divided into two spheres of influence:

- The eastern zone, with Syracuse, Agrigento, Mesina, was under Greek control.

- The western zone, where the Carthaginian colony of Panormos (Palermo) stood out... was under the control of the public.

Something similar happened with the Greek attempts to establish colonies facing the Tyrrhenian Sea. Although the beginnings in Corsica and Sardinia were promising, with the founding of Alalia and the establishment of a base in Olbia (Sardinia), the defeat against the Etruscans and Punics at the Battle of Alalia left Corsica and Sardinia in Carthaginian hands. The new masters of the western Mediterranean concentrated in the south of Sardinia, creating the Punic colonies of Cagliari, Nora, Sulcis and Tharros.

The new Greek colonies imported the government of polis (city-states), often competing or even facing each other. Thus the rich Síbari was defeated by Taranto, which became one of the powers of the peninsula. It was not infrequent that other Greek powers were asked for help to fight enemy colonies or the Italic peoples, highlighting campaigns such as those of Archidamus II or that of Alexander of Epirus. But the largest Greek colony would be Syracuse, which, ruled under a series of tyrants such as Dionysius I, became the great power of Sicily, repelling an Athenian expedition in 415 BC. C., despite Athens being at the height of her power and leading the fight with the Punics.

From the IV century B.C. C., in the same way as the Etruscans, the Italiotes of Magna Graecia, like all the Italic peoples of southern Italy, were gradually conquered, absorbed and federated by the Roman Republic, thus becoming an integral part of Roman Italy..

Later, this population movement from Greece to Italy would be repeated at other times in history, given the proximity between the two countries. In the Middle Ages, during the centuries of Byzantine rule and the subsequent Greek emigrations due to the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans, new waves of Greeks arrived who found in southern Italy a brother people with common roots and, sometimes, Greek-speaking (see: grikos from southern Italy). Naples, especially, would be for centuries one of the largest ports in the Mediterranean and a focus of Greek culture.

Rome

Origins

In 753 B.C. C. was founded, on the banks of the Tiber river, in the central part of the Lazio region, in central Italy, a key city for the history of humanity: Rome.

Based exclusively on its legendary origin: Roman mythology links the origin of Rome, and its monarchical institution, to the Trojan hero Aeneas, who, fleeing the destruction of his city, sailed into the western Mediterranean until he reached Italy after a long journey. There, after marrying the daughter of the king of the Latins, a town in central Italy, he founded the city of Lavinium .

Later, his son Iulo, would found Alba Longa, a city from whose royal family the twins Romulus and Remus would descend, sons of Rhea Silvia and the god Mars, who, after having been abandoned in the Tiber river by their mother, Saved and nursed by a wolf named Luperca, and raised by the shepherds Faustulo and Acca Larentia, they settled between the Palatine and Aventine hills, where they had a violent argument and, after Remus was murdered by his brother Romulo, this Last, on April 21, 753 B.C. C, he founded Rome.

According to contemporary historiography and archaeology, the real origin of Rome is due to some settlements of Italic tribes of Latins, Sabines (hence the legendary episode of the kidnapping of the Sabine women) and Etruscans, who, between the X and VIII a. C., settled at the point of Latium Vetus that would become Rome, between the seven hills and the confluence between the Tiber river and the Via Salaria, 28 km from the Tyrrhenian Sea. In this place the Tiber has an island where the river can be crossed. Due to the proximity of the river and the ford, Rome was at a crossroads of traffic and commerce. Around the 8th century BC. C. the settlements were unified in what is known as Roma Quadrata.

The Roman Monarchy

The Roman monarchy (in Latin, Regnum Romanum) was the first political form of government of the then city-state of Rome, from the legendary moment of its foundation, on April 21, 753 to. C., until the end of the monarchy, in 510 a. C., when the last king, Tarquinio the Proud, was expelled, establishing the Roman Republic.

The origins of the monarchy are imprecise, although it seems clear that it was the first form of government for the city, a fact that archeology and linguistics seem to confirm. Mythologically, it is rooted in the legend of Romulus and Remus. In any case, after Romulus and the Sabine Numa Pompilius, Tullius Hostilius came to power, expanding Rome's port of call on the coastal salt route, at the expense of its neighbors, transforming Rome into the most influential city in Lazio.

After the reign of Ancus Marcius, a dynasty of Etruscan origin, the Tarquins, rose to power, under which Rome further expanded its power in the region. However, the excesses of Tarquinio the Proud were the source of internal disputes, to which was added the coalition of Etruscans and Latinos threatened by the city, leading to the expulsion of the king thanks to the intervention of Lucio Junio Bruto and Lucio Tarquinio Colatino. Rome lost most of its power to the Etruscans led by the king of Chiusi, Lars Porsenna, to which was added the humiliation of a sack by Celts led by Breno, who devastated several Italian cities.

The Roman Republic

The Republic (509 BC-27 BC) was the next stage of ancient Rome in which the city of Rome and its territories maintained a republican system of government. Under unclear historical circumstances, the Roman monarchy was abolished, in 509 BC. C., and replaced by the Republic.

A characteristic of the change was that the administration of the city and its rural districts became regulated in the right to appeal to the people against any decision of a magistrate concerning life or legal status. The executive administration was endowed with Imperium or all-encompassing power which had a religious origin that stemmed from the god Jupiter himself. The magistrates endowed with imperium were the consuls, praetors and, eventually, the dictators. However, the imperium was only exercised extra pomoerium, that is, outside the walls of Rome. Consequently, it had an essentially military character. In the city, and in their civil functions, the magistrates were subject to legal limitations and mutual controls.

Over the years, the city conquered its Latin, Sabine and Etruscan neighbours, whom it would group into the Latin League, and recovered its former power in Lazio. Expansion continued south and, accepting a request for protection from the Capuan Samnites from their mountainous neighbours, he became involved in the Samnite wars, which he would eventually win Campania. The Greek city of Naples reached a similar agreement. To secure the conquered territory, Roman colonies were founded in various parts of Italy, such as Ostia, Urbinum Mataurense (Urbino), Aruminium (Rimini), Cremona, Placentia (Piacenza) or Mediolanum (Milan). One by one the various Italic peoples were conquered and federated, Rome imposed a protectorate over the southern Greek colonies, headed by Taranto, which despite the campaign of King Pyrrhus of Epirus, ended up in the same way as the other Italics under the Roman yoke..

With this, Rome completed the conquest of peninsular Italy which, from now on, will remain as an enlarged extension of the ancient Ager Romanos, that is, as a metropolitan territory of Rome itself, politically differentiated from any other territory outside of it, which will be the provinces.

The request for help from the Mamertines, a group of mercenaries who had taken over Messina, caused the Roman advance to continue towards Sicily, where it collided with the Carthaginians. After winning the first Punic war, three-way between Rome, Carthage, and Syracuse, Rome annexed most of the island. It was soon followed by Sardinia and Corsica, given the weakness of Carthage during the War of the Mercenaries, and Syracuse itself, after the fall of its tyrant Hieron II of Syracuse, and his famous siege. Having become one of the main powers in the Mediterranean, along with Carthage and the Hellenic kingdoms, Rome practiced an increasingly important foreign policy. The Illyrian Wars, in the Adriatic, and the first serious clashes with Macedonia and the tribes of Gaul date from that time.

The Carthaginian rearmament, led by Hamilcar Barca, led to the Punic occupation of much of the Iberian Peninsula and a new period of rivalry with Rome. With the excuse of the siege of the Roman allies of Sagunto, Hamilcar's son and successor, Hannibal, would invade Italy through the Alps. During this second Punic war, Hannibal inflicted historic defeats on the Romans, culminating in Cannae, but finally the victorious campaign of Publius Cornelius Scipio prevailed in Iberia, which ended up transferring the war to North Africa and led to the final victory of the Romans in Zama.

Rome was, from then on, the greatest Mediterranean power. He annexed the Carthaginian provinces in the Iberian Peninsula, which he expanded through various wars in the following two centuries, during his conquest of Hispania, despite setbacks such as the Siege of Numancia or the resistance of Viriato. Rome began to intervene in Greece and Macedonia, during the Macedonian wars, conquering them after a victory at Pydna. After a third Punic war, long sought after by the most conservative sector of the Senate and its spokesman, Marco Porcio Cato, with which he definitively destroyed his old Carthaginian enemies, Rome thus set foot in Africa, in what is now Tunisia.

The inheritances of King Attalus III in Asia and Nicomedes in Bithynia gave him new territories in Anatolia, which led to another war with Mithridates VI of Pontus and Tigranes I of Armenia, with which his domain was extended to Syria and Turkey, while conquering its former Numidian allies, led by Yugurtha, who had turned against Rome. The same would happen with the kingdom of Cyrene, together with Egypt, bequeathed to Rome by its last king, Ptolemy Apion. The need to maintain the routes that connected these territories led to campaigns against pirates and to occupy Cilicia, to ally and make protection pacts with cities such as Marseille or Rhodes, and to the conquest of Gaul Narbonensis. Publius Clodius Pulcher would eventually lead the occupation of Cyprus, a remote Egyptian province subjected to the ups and downs of Mediterranean politics. The construction of Roman roads facilitated communications, both in Italy and in the provinces.

This incombustible expansionism of the Republic had important social consequences, mainly due to the fact that the Roman army was not designed for long overseas campaigns. The absence of their homes had harsh consequences for the Italic confederates who made up the base of the Roman army, both among the Italics with citizenship (who made up the legions) and, and above all, among the Italics socii (the allies, still without citizenship and who made up the alae sociorum, the majority base of the Roman army).

This led to the Italic rebellion of the socii (allies), dissatisfied for not having received citizenship yet despite the fundamental contribution offered for the conquest of the provinces, as well as for the quarrels with the other Italics already citizens, triggering the Social War (or Allies' War), that is, the war between Rome and the other Italic cities already provided with citizenship against their Italic allies without citizenship, which led to the granting of the full Roman citizenship for all Italics, through the Lex Plautia Papiria; event that further highlighted the differentiation of status between Italy (already a metropolitan territory of Rome exempt from provincial taxes and, after the aforementioned Social War, inhabited entirely by Roman citizens with full rights) and the provinces (the remaining territories outside Italy). Italy).

In the same period, Metellus's army had been assigned to the senior consul, Lucius Cassius Longinus, to drive out the Cimbri, who were again threatening Italy from the Alps. Key Mario introduced a series of important reforms.

Mario crushed the Germans in the battle of Vercelae and became the first man in Rome of his time, consul five times in a row, but at the cost of a greater degree of political confrontation. Mario, of humble origin, represented the success of the popular classes against the traditional Roman aristocracy, which opposed him, aggravating a confrontation between social classes that dated from the very origins of the city.

The demands of the poorest classes, who since the attempts at agrarian reform by the brothers Tiberio and Cayo Sempronio Graco aspired to the distribution of public lands as a result of the conquests that benefited the landowners, and the new army, which depended on the power of his general to obtain land upon graduation, gave rise to a series of conflicts and internal drives. Lucio Cornelio Sila, Mario's former lieutenant who confronted him in his last years leading the patrician aristocracy, restored peace after a personal dictatorship, but over time his measures were annulled. It is one of the most famous periods in the city, with the oratory of Marco Tulio Cicero in the Senate, the coup attempt by Lucio Sergio Catilina or the slave revolt of Spartacus.

The power accumulated by the triumvirate of Pompey, Julius Caesar and Crassus stands out, who shared public office in Italy and the government of its provinces. Crassus was defeated by the Parthians in the East at the Battle of Carrhae, but Caesar won immortal fame by conquering the warlike Gauls and setting foot in Britain and Germany.

The enmity between the politician and general who had conquered Gaul and amassed unprecedented power, and most of the aristocracy, led to a bloody succession of civil wars when they tried to dispossess him of command of his troops, prior alliance with his former ally Pompey. Caesar then crossed the Rubicon River, imposing himself in Italy, and persecuting those who opposed him through the domains of Rome. He won the key battle of Pharsalus and finally achieved absolute power, but was assassinated by a plot led by Marcus Junius Brutus that reinitiated the partisan struggle.

In the new civil war, the Caesarians persecuted what was left of their opponents while they disputed among themselves the succession. After a struggle with Caesar's former lieutenants Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Julius Caesar's adoptive son and successor, Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, seized power from the Caesar faction and Rome, ending the civil wars..

The Roman Empire

The birth of the empire is preceded by the expansion of its capital, Rome, which extended its control around the Mediterranean Sea, and the long succession of internal conflicts that marked the end of the Republic.

After Augustus's final victory, a lasting peace was finally established, characterized by the concentration of power in the hands of the aforementioned, first as Princeps and later as Domine. At the same time, internal pacification and external expansion continued, seeking what is known as Pax Romana, a long period of stability and peace that Europe, North Africa and the Middle East experienced under the Roman yoke. Augustus sought to consolidate and rationalize the borders and create an administration that would manage the already extensive territories under Roman power. For this he had the support of loyal collaborators such as the wealthy Cayo Maecenas or the general Marco Vipsanio Agrippa.

Succeeded by Tiberius, adoptive son of Augustus, the transmission of imperial power began in a single family, although successions were often given to adoptive sons, such as Augustus and Tiberius themselves. Tiberius turned out to be a tough and effective emperor, although somewhat unstable with a season absent on the island of Capri. He was succeeded by his adoptive son Caligula, natural son of the great general Germanicus. Initially acclaimed by all, he was soon famous for his megalomania, his follies and his excesses. Ultimately assassinated by a plot involving the Praetorian Guard, he was succeeded by his uncle Claudius, who was considered incapable but earned a reputation as a good ruler for his doing. In his last years he was marked by his wife and probable murderer of his, who managed to place Nero, Claudius's adopted son. Nero turned out to be a new Caligula, and after his death, in another coup, the year of the four emperors took place, which shows how fragile the imperial dynasty could be in the face of the army. Vespasian, a skillful general and politician, would finally prevail, replacing the Julio-Claudian dynasty with the Flavia.

His sons succeeded him, first the beloved Titus and then the cruel Domitian, who died in another conspiracy. After him came the so-called five good emperors, who took Rome to its territorial, economic and power culmination: Nerva; Trajan, who extended the borders of the Empire; Hadrian, beloved emperor who carried out great reforms and visited numerous provinces; Antonino Pío and Marco Aurelio, thinker as well as defender of the borders. The latter was succeeded by his natural son, Commodus, with whom many of the problems previously present in terms of successions and instability would reappear.

The year of the five emperors was followed by the new Severan dynasty, with emperors of provincial extraction such as Septimius Severus, who was an able general who reestablished the empire after the neglect of Commodus. He was succeeded by his son Caracalla, of military habits and a good general although unpopular for having killed his brother Publius Septimius Geta, and who was assassinated on campaign. For a couple of years the general who had assassinated him, Macrinus, held power with his son, but the Severa dynasty finally prevailed with Heliogábalo, a controversial worshiper of the Sun. So controversial was it that his own family supported his cousin and respected General Alejandro Severo. The new emperor, calm and peaceful, would end up leaving power in the hands of his mother and grandmother, who dedicated themselves to repairing the mistakes made during Heliogábalo's administration. He ended up being killed. It was the last civil government of Rome and the end of the Severan dynasty: with his death, in 235, fifty years of military anarchy began in the Empire. It is the so-called Crisis of the III century.

The Roman Empire was the greatest cultural, artistic, literary, philosophical, scientific, military, and technical focus of its time. The culture of Ancient Rome is not only relevant for the Law or the assumption of Christianity as the dominant religion; also, it was especially fruitful in the field of civil engineering; the first European road network was built when the Roman roads spread throughout the empire; Among the civil works, the bridges and aqueducts to carry water from the aquifers to the cities stood out. Roman urban culture allowed the development of extremely complex cities, both in Italy and outside of it.

Rome took over from Greek culture. Notable authors such as Virgil (author of the Aeneid, the main Roman epic poem), the historians Pliny the Younger, Pliny the Elder, Tacitus, Titus Livio and Suetonius, the poet Horace, the comedian Plautus or the philosophers and orator Cicero. The romanization of the occupied territories, both due to cultural superiority, military conquest and the creation of colonies, led to the spread of Latin throughout Europe and being the seed of the Romance languages.

Inversely, the Romans imported numerous knowledge from other peoples: Hellenistic philosophy, the Egyptian calendar... Roman syncretism imported numerous cults from everywhere such as the Anatolian Cybele, the Greek-Egyptian Serapis or the Phoenician Melkart. Towards the last years of the empire, oriental sects and cults such as Judaism, its Christian split, Mithraism or the cult of Sol Invictus gained importance.

The capital of Italy and of the entire Empire, Rome, became the largest city in the world of its time, and the first metropolis in history, with inhabitants coming from all the Roman provinces and numerous triumphal arches, such as those of Titus, Augustus or that of Trajan, columns like those of Trajan and Constantine and votive temples for military victories; numerous obelisks were brought from Egypt.

Foreign peace, security, and the communications network that included roads and maritime routes, boosted trade and the economy. Agriculture and livestock in ancient Rome continued the late republican process of concentration of land ownership in latifundia thanks to the distribution of conquered lands and the ruin of small farmers. Slavery was key in the exploitation of these large estates and another reason for Roman militarism. Roman engineering made it possible for the first time to exploit mines on a large scale in Hispania and Britain. With guilds primitive industries such as Roman glass, garum or purple were born. The existence of a series of states organized throughout Eurasia allowed the creation of the Silk Road, which linked the West with the Chinese Empire and India.

Under the imperial period, the domains of Rome continued to increase. Augustus, after the wars that brought him to the throne pitted him against Cleopatra, conquered Egypt, incorporated the former Roman protectorate of Galatia, and in his attempt to create a cohesive empire. he completed the conquest of Hispania against the Cantabrians and Astures, that of Noric and Rhetium north of the Alps, and the Danube basin (Panonia, Moesia and Thrace). Tiberius would incorporate Cappadocia as a province, which since the time of the Republic had depended on Rome to survive among the empires of the region. Caligula, in one of his excesses, assassinated the King of Mauritania and annexed the country. Claudius, trying to gain fame, invaded Britain, which would finally be conquered after several campaigns. Titus is famous for having conquered Judea, since the time of Caesar, an ally or Roman protectorate. The struggle with Rome marked many national milestones in those countries, such as the rebellion of the British queen Boudica, the campaigns against the Picts led by Gnaeus Julius Agricola or the last Jewish resistance at Masada. The empire reached its greatest extent during the reign of Trajan, conqueror of Dacia (present-day Romania) after the Dacian Wars, of Petra and Assyria, of Mesopotamia and Armenia after a war with the Persians.

The Roman Empire stretched from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the shores of the Black Sea, the Red Sea, and the Persian Gulf in the east, and from the Sahara desert in the south to the forested lands on the banks of the Rhine and Danube rivers and the Caledonian border to the north. Its estimated maximum area would be about 6.14 million km².

Over time the borders became more stable. The defeat before the Germans of Arminio in Teotoburgo, in times of Augustus, ruined the conquest of Germany projected by the emperor. The constant wars with the Parthian Empire in the east marked the final limit for the East, having to fight many wars with Persians or rebellious states such as Palmyra to preserve what was conquered. The difficulties in managing the already immense imperial territory led to the construction of limes, or fortified borders, to defend an empire that was beginning to show signs of exhaustion.

Trajan's successor, Hadrian, abandoned some of his conquests in the Middle East to better manage the empire and created Hadrian's Wall in front of the Scottish Picts. Marcus Aurelius spent a good part of his reign fighting in the Marcomannic wars against the Sarmatians in the East and the Marcomannics on the Danube, as the pressure of the Huns pushed these and other tribes (Goths, Alans...) against the borders of the Empire.

The Late Empire and the decline

The period known as the Lower Empire (284-395) begins with Diocletian, who was Emperor of Rome from 284 to 305. Diocletian, to facilitate the administration of the Empire, devised the Tetrachy, dividing the Empire between West and East. He inaugurated the Constantinian dynasty (305-363), named after the most important of his emperors. After her, the Valentinian dynasty (364-395) and the Theodosian dynasty followed.

Since Diocletian, the empire was united and separated again on various occasions, following the rhythm of civil wars, usurpers and distributions between heirs to the throne until, on the death of Theodosius I the Great, who made Christianity non-Arian the official religion, was definitively divided.

The wave of eastern peoples ended up pushing the Germanic tribes, pushed to the West, which several times penetrated an increasingly weak Roman Empire. The borders gave way for lack of soldiers to defend them, after Caracalla had extended Roman citizenship to the entire Empire in the 3rd century span>, letting Italy (and with it Rome itself) gradually lose its differentiation with the provinces.

On many occasions border provinces were ceded to the Germans in exchange for them defending them from their compatriots (establishing foedus with them), since military service had been abolished among the Italians. Other times it was seen how generals proclaimed themselves emperors in Gaul or Britain, a province that was finally abandoned to concentrate the troops on the continent. The Empire, sophisticated and rich as few in history, was already decadent, and in the III and IV, its last glories came from generals of barbarian origin such as Aetius, who defeated Attila in the battle of the Catalaunic Fields and Stilicho, who managed to the last victories against the Germans.

In the Middle East, Zenobia's rebellion in Palmyra and the wars with the Sassanids put the Empire in trouble several times. The Rhine border was crossed by the Franks one day when the river froze and the Danube border yielded to the Goths, who caused a historic defeat to the last legions in the battle of Adrianople. At the height of weakness, Italy itself was attacked. The glorious city of Rome was sacked by the Visigoths of Alaric I in 410. Attila attacked the peninsula, devastating Aquileia (whose fugitives were the seed of the thriving Venice since then) and reached Rome, which, however, did not attack after a parliament with Pope Leo I the Great.

At the same time, the capital had been displaced first to Milan, and later to the easily defendable Ravenna, while various provinces were being conquered by various Germanic peoples or directly abandoned by the central power. The richer and militarily stronger eastern part became the great focus of power in the Mediterranean, the nascent Byzantine Empire, at the cost of reducing the resources of Italy and the West. Christianity, once persecuted, became the official religion thanks to Constantine I the Great's edicts in Milan in 313, which proclaimed religious freedom, and Theodosius I the Great's in Thessaloniki, which made Christianity official in 380. Bishop of Rome, the pope, began to gain political importance and to be one of the main Christian leaders. The cities decayed, producing an emigration to the countryside, with the consequent negative effect on commerce, culture and science.

The Emperor of Rome no longer controlled the Empire, so in the year 476, a barbarian chief, Odoacer, deposed Romulus Augustulus, a 10-year-old boy who was the last Western Roman Emperor and sent the Imperial regalia to Zeno, Eastern Roman Emperor.

High Middle Ages (5th to 12th centuries)

The Ostrogothic Kingdom

The Ostrogoths were a group of Goths who had been subjugated by the Huns. After their liberation from those, they chose Teodomiro as king and settled under Byzantine protection in Pannonia, on the Danube. He was succeeded by his son Theodoric the Great, who with the blessing of the Eastern Emperor led his people to Italy in 488.

The Heruli Odoacer ruled the peninsula after deposing the last Roman emperor in 476. After a campaign in the north of the peninsula, Theodoric took the capital, Ravenna, killing Odoacer in 493 and establishing himself as lord of the country. His reign was remembered for maintaining the Roman administration, which he protected, managing to maintain the stability of the West. Regent of his Visigothic cousins as grandfather of the young king, Theodoric, he came for a time to seem capable of rebuilding the old Western Empire. He ordered the construction and decoration of jewels such as the Archiepiscopal Chapel of Ravenna, the Arian Baptistry or his mausoleum, a masterpiece of Ostrogothic art in Italy.

However, in 526, Theodoric's death ended this period of peace, and Italy was inherited by his grandson, Athalaric. The Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy collapsed, with Theodoric's nephew, Theodatus, murdering Atalaric, the great king's grandson and heir, and starting a civil war. The excesses of Theodatus broke with the support of the Eastern Roman Empire to the Ostrogrodo domain and led to a Byzantine invasion parallel to the noble struggles.

The Byzantine Exarchate

Under Justinian I, the Byzantine Empire began a series of campaigns with the aim of rebuilding Mediterranean unity, and mainly with the attempt to recover Italy, center of the old Empire. The weakness of the Ostrogothic kingdom, and the Byzantine desires to recapture the city of Rome, made Italy a target. The Ostrogothic civil war gave him the opportunity to intervene in the Gothic war, for which he sent his best general, Belisarius.

In 535, Belisarius, had invaded Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, within his campaigns against the Vandals, and from there he marched across the peninsula, entering Reggio di Calabria, taking Naples (where the Ostrogothic usurper Theodato fell). and reaching Rome in 536. Blocked there, he had to hold the position until the arrival of reinforcements, which landed at Rimini, turned the tables. He proceeded north and took Mediolanum (Milan) and Ravenna, in 540 killing the new Ostrogothic king, Vitiges. An agreement with the Ostrogoths, who retained a kingdom in northwestern Italy, brought peace.

Belisarius was then called to the East, where the Persians threatened the borders. His successor, John, failed to maintain control at a time when the Byzantine Empire was short of resources, and in 541 the Goths were at odds with Byzantium again, led by an energetic king named Totila who had recaptured Northern Italy and taken Rome. The return of Belisarius allowed Rome to be recovered, only to lose it again not long after.

In 548, the eunuch Narses replaced Belisarius. Totila was killed in 552, and the army of the last Gothic king, Teias, was defeated in 553. By 561 the Byzantines had pacified the area.

The Byzantines controlled Italy from their capital at Ravenna, under the Exarchate of Ravenna. Byzantine art left significant traces in Italy such as the churches of San Nicola in Carcere and Santa Maria in Cosmedin in Rome; the church of San Vital in Ravenna or the basilica of San Apollinare in Classe in the same city. The group of late Roman, Ostrogothic and Byzantine buildings in the city of Ravenna is today a World Heritage Site.

The Lombard Kingdom

Among the different Germanic peoples who had abandoned their former home to live in better lands, there were the Lombards (or Longobards), whom Justinian I had allowed to settle in Pannonia, on condition that they defended the border. Attracted by the wealth of Italy and the pressure of the Avars, they crossed the Alps, occupying the current regions of Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy and Veneto, without much opposition. Milan, the center of northern Italy, fell in 569. It was succeeded by the fall of Tuscany, Spoleto in the center, and Benevento in southern Italy. Longobardia Maior is called the area of northern Italy, where they established their capital, Pavia (the Lombardy region is still called that way today), while Spoleto and Benevento, their outposts in central and southern Italy, were known as Longobardia Minor.

The new lords of Italy organized their possessions into Lombard Duchies, such as the Duchy of Friuli, the Duchy of Tuscia, the Duchy of Spoleto or the Duchy of Benevento, under the authority of a king in Pavia. The lack of a central authority during the rule of the dukes made possible the fragmentation of Italy into thirty-six quasi-independent duchies, separated by strips of territory in the hands of the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna. Although the Lombard kingdom once again had a king, the central power was always weak.

Thus, while facing the opposition of the territories of the Byzantine Empire in the East, and that of the Franks, a rising power in the West, the Lombards managed to recompose a common elective monarchy, traditionally Germanic. It is worth noting the reign of Agilulfo who abandoned Arianism and converted to Catholicism, generating religious persecutions between both confessions.

While the iconoclastic conflicts occupied Byzantium and made it antagonistic to the Pope (since the position of the Emperor of the East also governed his Italian lands), the Lombards increased their domains, under the pretext of helping the Pope. In 750 Aistolf took the imperial city of Ravenna.

From this period of the High Middle Ages, and with the diffusion among the people of the Romance languages (of the Italo-Romance languages and Gallo-Italic, in the case of Italy), the Italian demonym takes the place of the old Italic demonym, used until then.

The Franks and the Kingdom of Italy in the Carolingian Empire

The pressure of the Lombards on the pope caused the king of the Franks, Pepin the Short, to carry out repeated campaigns in northern Italy between 756 and 758. The pope, in gratitude, confirmed him as king of the Franks (despite having usurped the title) and granted the rank of patrician to the family that had seized the Merovingian throne in France.

The situation escalated after Pipino's death. The Frankish kingdom was divided among his sons, again increasing Lombard pressure on the papacy. However, the reunification of the Franks under Charlemagne led to a new intervention in Italy in 774. After a brief battle, Charles seized the kingdom of Lombardy, which, while maintaining its autonomy, was integrated into the Carolingian Empire, which with time would unite most of Western Europe. Charlemagne fostered a cultural renaissance and a political and religious unity, which crystallized with his coronation as Emperor of the West by Pope Leo III, in the year 800. His new empire was considered the heir to the Western Roman Empire., being the emperor the highest temporal authority in Europe and in charge of watching over Christianity.

Since then, northern Italy was part of the Carolingian territories, under the name of the Kingdom of Italy.

The Papal States

Since the time when Constantine I made Christianity the official religion, the power of the Church had been increasing in Italy. The Donation of Constantine, a historical forgery, was the basis for the pope's claims to temporal power over the city of Rome, which gained strength as the emperors abandoned it. As an example, Attila parleyed with Pope Gregory I the Great when approaching the city. Already in Byzantine times and in the midst of iconoclastic confrontations, the duchy of Rome was eliminated, winning the city Gregorio II, with recognition of his government by the Lombard king Liutprando. It was the Patrimony of San Pedro.

Given the occupation of the territory by the Lombards, the help of Charlemagne and the Franks to Leo III was vital. Thus began Caesaropapism, a close relationship between the Pope and the Emperor. Part of the lands seized from the Lombards were ceded to the Pope, who then created a State in the center of Italy, the Papal States, the historical seed of the current Vatican City. These were administered directly by him or through vassals.

The government of these territories went through a key phase during the period known as pornocracy. This period is characterized by numerous struggles for power in the Church, Rome, and central Italy; among intriguers often motivated by courtesans and nobles (particularly the lords of Spoleto). It begins in the year 904 with Sergio III and his lover Marozia and dates to the imprisonment in 935 of John XI by the Duke of Spoleto Alberico II, both sons of Marozia.

The southern context and the rise of the Kingdom of Sicily

The southern Lombard duchies were never conquered by Charlemagne, who had to march north to fight the Saxons, and they were not part of his empire. The Lombard dukes of Benevento maintained their independence, eventually becoming the Principality of Benevento and pushing the Byzantines south. However, the assassination of Duke Sicardo de Benevento divided the state between his brother, Siconulfo de Salerno, who was proclaimed Prince of Salerno, and his assassin, Radelchis, who seized power in Benevento. The division allowed nobles in Gaeta, Capua and Amalfi to gain autonomy, who formed their own principalities and duchies. The remaining southern territories, such as Naples, Sicily and the southernmost part of the Italian peninsula (Apulia and Calabria), remained a Byzantine province.

At the same time, southern Italy came into contact with Islam, initially as a victim of raids from North Africa. Sardinia was occupied by the Arabs in 710 after being left to its fate by the Byzantines, but 70 years later, taking advantage of the distance from the Arab bases, an island revolt took place that established local governments known as giudicati. Corsica also suffered Muslim attacks, combined with Frankish, Lombard interventions and the Marquis of Tuscany Bonifacio II, to secure the border.

In 826, a Byzantine defector offered Sicilian territory to the Muslim Emir of Ifriquiya, which would lead to a series of wars. By 965 the island had been converted into the Emirate of Sicily, from which attacks were launched on the ports of the peninsula. The Byzantines reformed their possessions in the southern part of the peninsula after repelling one of the Muslim attacks on Bari in 876, creating the Catapanato of Italy, at war with Muslims and Lombards.

The situation changed with the arrival of the Normans. Various legends surround their arrival, the most famous being the one that describes them as pilgrims from the north who offered themselves as mercenaries to the Lombards. Initially they served these, but in the words of Amatus of Montecassino:

The Normans never wanted any of the Lombards to win a decisive victory, which would have left them at a disadvantage. But supporting one and then helping another prevented anyone from being totally ruined.

Soon they were lords of positions conquered from the Byzantines and Lombards, leading to the Norman conquest of Southern Italy, with the Norse establishing a State in Naples led by Roberto Guiscardo. From there they crossed the Strait of Messina and managed to reconquer Sicily from the Muslims, which would form part of a unified kingdom when Roger II of Sicily united both thrones in the Kingdom of Sicily in 1130. The kingdom would be a cultural amalgamation of Latin, Lombard, Greco-Byzantine and Norman substratum, like its art, exemplified in the Cathedral of Cefalù, the Palatine Chapel of Palermo and the Cathedral of Monreale.

At the end of the 12th century the kingdom passed to the Imperial German Hohenstaufen dynasty, when Emperor Henry VI claimed the throne in 1212 for being his wife Constance I of Sicily, heiress to the kingdom.

Late Middle Ages (12th to 15th centuries)

Guelphs and Ghibellines, the Holy Empire and the Lombard League

The death of Charlemagne and the struggles to retain his empire divided among his various sons began a period of civil wars that did not stabilize until the creation, at the beginning of the century X, of the Kingdom of France and the conglomerate of the Holy Empire in what is now Germany, northern and central Italy, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and other eastern territories of its former domains. The absence of a strong central power meant the atomization of these regions into principalities, bishoprics, counties and cities that were practically independent and often at odds with each other. This was particularly important in Italy, where the wealthy northern cities emerged as quasi-independent trading city-states. The emperor was chosen by the main nobles, which facilitated this climate of confrontation that had Italy as a battlefield on numerous occasions.

In the X century, a new element of contention was introduced: the confrontation between the Church and the Empire, which it was known as the Investiture Complaint of 1073, which started a series of conflicts over the primacy of the pope or the emperor in Christendom and the Holy Empire. Both discussed the theoretical submission of imperial temporal power to papal religious power or vice versa, and the right to appoint bishops. The struggle divided Italy between Guelphs (for the Welfen of Bavaria), who supported the pope, and Ghibellines (for the Hohenstaufen of Waiblingen), the defenders of imperial power. As a result of this, various emperors confronted the pope and invaded Lombardy, supporting antipopes when it suited them. In response, various emperors were excommunicated, while the Papal States rejected the temporal power of the emperor and promoted pro-church factions.

Cities such as Florence, Milan, and Mantua embraced the Guelph cause, while others such as Forli, Pisa, Siena, and Lucca joined the imperial cause. It was generally a struggle for autonomy, where the cities that feared the power of the emperor tried to counteract it with papal influence, and those close to Papal Lazio sought an imperial authority that would guarantee their freedom. Other times, it was the internal fights between rival cities that turned local quarrels into new episodes of this confrontation: the Guelph Florence put up a battle with the Ghibelline league of the other Tuscan cities (Arezzo, Siena, Pistoia, Lucca and Pisa), causing a long conflict that had as its greatest exponents the battles of Montaperti, in 1260, (which is celebrated in the famous festival of the Palio di Siena) and that of Altopascio, in 1325. However, many times, within a city both coexisted tendencies alternating according to the one that was stronger at the moment. Over time, sub-factions even developed within each group.

Enrique IV, began the lawsuit when confronting Gregory VII. He came to appear barefoot and in penance before him during the Paseo de Canossa in 1077, to get his excommunication lifted, but then he returned to support Antipope Clement III against Gregory and his brother-in-law Rodolfo de Suabia. The following popes failed to defuse the conflict, until Calixto II achieved peace with the son and successor of Henry IV, Henry V, with the Worms Concordat. Its terms differentiated between the canonical coronation of the emperor by the pope and the secular, and the authority of the emperor over the Church in Germany was admitted, after Henry's invasion of Italy in 1110.

After the Enriques, Lotario II ruled, defeated by Rogelio II of Sicily and faced Conrad III. This nobleman was the first Hohenstaufen family that began to accumulate power in Germany. Probably the greatest confrontation between pope and emperor occurred with his son Federico I Barbarossa, emperor between 1155 and 1190, whose active Italian policy accentuated imperial intervention. Northern Italian cities became involved in the war, frequently changing parties. The Lombard League was an alliance established on December 1, 1167 between 26 Opposing Cities in northern Italy, including Milan, Cremona, Mantua, Bergamo, Brescia, Piacenza, Bologna, Padua, Treviso, Vicenza, Verona, Lodi, Parma and Venice. Four more cities were later joined, making a total of 30. The initial purpose of the League was to combat the Italian policy of Federico I, who at that time claimed full control over northern Italy. The imperial response was expressed in the Diet of Roncaglia, and was carried out with the invasion of 1158 and then again in 1166. The League received the unconditional support of Pope Alexander III and his successors, eager both to be freed from the influence imperial as well as to increase its power in the Italian peninsula. In the battle of Legnano (May 29, 1176), the imperial troops were defeated, and Federico was forced to sign a truce of six years (1177-1183). The situation was resolved at the end of this, when both parties signed the Treaty of Constance, according to which the Italian cities recognized the sovereignty of the Emperor of Germany, but in turn he was forced to recognize the jurisdiction of each city over itself. and its surrounding territory, which meant the recognition of its de facto independence.

After Barbarossa, his son Henry VI would reunite both the German kingdom and that of Sicily, by his marriage to Constance I of Sicily. The Guelph Otto IV would rule briefly (1208-1218), leaving the Duchy of Spoleto under papal rule in 1213, but he ended up turning away from the papacy and trying to restore imperial authority in Italy, only to fall to the Ghibelline Frederick II Hohenstaufen, King of Sicily and son of Henry VI. With Frederick II, Stupor Mundi (the astonishment of the world), the Hohenstaufen regained the German imperial throne. Federico II regrouped some Abruzzo towns to found the city of L'Aquila in 1254, reorganized the Kingdom of Sicily with the Constitutions of Melfi, and founded the University of Naples. The pope's attempt to rally the Guelph cities against him triggered a new imperial invasion in 1229, which was followed by further fighting and even an excommunication of Frederick in 1239. Toward the end of his life, Pope Innocent IV succeeded without however a victory at the Battle of Parma. His death in 1250 marked an interregnum on the imperial throne, as his son Conrad IV and his grandson Conradin of Hohenstaufen faced the pope in Germany and Italy.

Henry VIII ended the interregnum when he was elected emperor in 1308, and despite belonging to a different dynasty, he once again clashed over Italy with the Church. The pope, Clement V, this time had the support of Sicily, which, despite the dispute with the Crown of Aragon, was in the hands of the pro-ecclesiastical Anjou of France. In 1314 Louis IV of Bavaria was elected, who welcomed theologians opposed to the pope such as Marsilio de Padua or Miguel de Cesena, and faced Pope John XXII. He supported the antipope Nicholas V against him, while the pope supported Charles IV of Luxembourg as King of the Romans. He acceded to the throne in 1355, with the support of the pope. His son, Wenceslaus of Luxembourg, had to face the growing independence of the Italian nobles and the Western Schism from the beginning of his reign as King of the Romans in 1376. In 1400, he was deposed by Robert of the Palatinate, who was defeated by Gian Galeazzo Visconti when he tried to impose his authority on Milan. Sigismund of Luxembourg came to power in 1410, reverting to the title of emperor, and reigned until, in 1437, Frederick III of Habsburg began the since unbroken succession of emperors from the Austrian Habsburg family.

Italian City-States: Comuni and Signorie

Thus, these continuous conflicts gave the opportunity to forge autonomous city-States, governed by republics (Comuni) or by local noble rulers (Signoria), which thanks to the confrontation between the great powers of the time, they were not subservient to anyone. Contemporary historians often associate the Signorie with the failure of republics to maintain law and order. It was not uncommon for a city to offer itself to a powerful leader to guarantee its prosperity: Pisa later did so with Charles VIII of France and Siena with César Borgia under pressure from their Florentine enemies. Each city maintained its peculiar balance between one government and another with different power of the rulers. Sometimes a nominal republic masked the control of a small aristocracy or even a single family. Florence was a republic controlled however by the Medici family, the richest in the city. In others, directly the hereditary rights of a family were part of the right of the city as in modern monarchies.

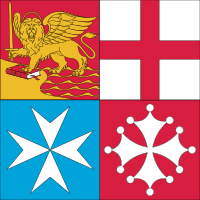

The delicate balance between the Church, the local nobility, and a fluctuating petty bourgeoisie, with conflicts allowed the establishment of republics such as the Republic of Pisa, whose sea laws are recognized by the pope in 1077, the Republic of Lucca, born in 1119, or the Republic of Siena in 1125, all three in the Tuscany region. Bologna, seat since 1088 of the oldest university in the West, also had a republic, alternating with times under the orbit of Milan or the papacy. Coastal cities such as Venice, Genoa, Ancona or Amalfi, created a particular subtype of republics, the maritime republics, strongly linked to international trade. In a way that was not sustained over time, many other Italian cities alternated noble governments with revolutions and republics of different durations.

Particularly key was the evolution of Milan, which would become the greatest power in northern Italy. The lordship of Milan was in the hands of the Della Torre family, who lost it when confronting the city's archbishop, Otto Visconti. With the rise of Otto and his nephew, Mateo I Visconti, head of his armies, in 1277 the reign of the Visconti began. They supported the emperor in northern Italy, eventually besieging Genoa in 1318. Azzone Visconti would conquer the papal cities of Bergamo, Cremona, and Lodi, expanding his power in the region.

Other dynasties also took advantage of the events to found states in northern Italy. The House of Savoy, a Burgundian family that had unified the March of Turin and the County of Savoy, achieved the ducal title of Emperor Sigismund in 1416. The Montefeltro family controlled Urbino and Pesaro from 1213, being awarded the title of dukes in 1443 from Urbino. Ravenna, which was under papal rule, fell in 1218 to the Traversari, who were replaced in 1270 by the Da Polenta. Rimini fell into the hands of the Malatesta family in 1239, who from 1285 also ruled Pesaro and temporarily occupied Ancona. Camerino, destroyed in 1256, was since its reconstruction, in 1262, led by the Varano, who turned it into the Duchy of Camerino. The Gonzaga family took control of Mantua in 1328 under Luigi Gonzaga, which they eventually converted into a marquisate and duchy. The House of Este, vicars of the pope in Ferrara since 1332, received the government of the Duchy of Modena from Emperor Frederick III of Habsburg in 1452, and the Duchy of Ferrara from Pope Paul II in 1471. The Baglioni controlled, except for interludes, the city of Perugia since 1393.

Many of these noble estates were, at various times, subdued or annexed by the Milanese (both in the Visconti and Sforza eras), who became the main power in Lombardy. Pavia, Alessandria, Lodi and Parma became dependent on the Duchy of Milan. Various members of the Visconti family intervened in Sardinia. The zenith of this domain was the reign of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, who reached the maximum territorial expansion after the wars against the lords of Padua, in Veneto, and Florence in Tuscany. He conquered Verona, Vicenza, Bologna and temporarily Padua. He bought the title of Duke of Milan in 1395 for one hundred thousand florins from the Emperor Wenceslaus, and defeated his successor Robert when he tried to end his power.

After his death, however, the decline of the Visconti began, as they gradually lost territory. Venice, which had begun its expansion in Veneto, eroded Milan's possessions in eastern Italy. The attempt of his son, Filippo Maria Visconti, to conquer Romagna in 1423, made him confront the emperor and lose Bergamo and Brescia. When, with his death, the Visconti dynasty came to an end in 1447, Milan became the Ambrosian Republic, despite the claims of the duke of Orleans, legitimate heir. Orleans was unable to take possession of the inheritance from him, but the Republic was short lived. The adventurer Francesco Sforza, married to a daughter of the last Visconti, took Milan in 1450 and proclaimed himself duke, in confrontation with the French claimants.

Like most of Europe, Italy was ravaged at the time by the Black Death, which in 1348 caused serious demographic damage, wiping out a third of the country's population. Culturally, this troubled era laid the foundations for the following cultural splendor, highlighting the poet Dante Alighieri and his Divine Comedy, one of the classic works of the Italian language, dating from these times.

Sicilian Vespers and the rise of the Kingdom of Naples

On the death of Conradin of Hohenstaufen in 1266, the papacy maneuvered to place Charles of Anjou, brother of the King of France, on the Neapolitan throne, in order to end the Ghibelline imperial influence in the kingdom. This papal interference was opposed by Manfred I of Sicily, the king's son, who achieved some initial successes in his fight, but was definitively defeated – and killed – in the battle of Benevento. Opportunity led the Aragonese king, Pedro III, to claim the kingdom, his wife being his daughter of the last representative of the legitimate dynasty. Carlos was unpopular for his taxes and his administration, and this, in 1282, earned him a fierce popular revolt known as the Sicilian Vespers. Pedro then went to support the Sicilian rebels, winning the throne of the insular part of the Kingdom of Sicily. In 1302 the Peace of Caltabellota left the island to the Aragonese dynasty, while the continental part of the Kingdom of Sicily until then – now known as the Kingdom of Naples – to the Anjou. As was typical in the Crown of Aragon, the new insular territory ended up in the hands of a minor branch of the royal family, Pedro being succeeded by his second son, Jaime II of Aragon. In Naples, the Anjou reorganized the administration and protected the universities and culture.

On the death of Roberto I of Naples there was a war for the succession between Juana I of Naples and Carlos de Durazzo, who gave a brief government to Luis II of Anjou and finally gave the throne to Ladislao I, who would impose his authority to central and northern Italy. With the death of Ladislao, in 1414, Naples lost its conquests and left a queen without heirs.

Following a concession by Pope Boniface VIII, who tried to reunify the Sicilian kingdom in 1295 with the Peace of Anagni, giving James II of Aragon Corsica and Sardinia in exchange for his resignation from Sicily, the Aragonese intervention began in Sardinian and Corsican territories. The Sicilian opposition to the Anjou caused the Aragonese to continue on the Sicilian throne with Federico II of Sicily. On the other hand, the Aragonese domain over Sardinia and Corsica was disputed by maritime powers such as the Republic of Pisa (whose bishop had also received Sardinia from Gregory VII as a donation during the Investiture War) and the Republic of Genoa, whose commercial interest clashed with the previous ones. Effective domination meant long wars and dynastic conflicts. Corsica, which was not effectively occupied by the Crown of Aragon, ended up being handed over to the Republic of Genoa in 1347 in exchange for protection.

It was Pedro IV of Aragon, the Ceremonious, who again managed to unite Majorca and Roussillon to the main trunk, and pacify Sardinia. His son and successor, Martin I of Aragon, reunited Sicily and Aragon with his marriage to Eleanor of Sicily. In addition, his victory in the battle of Sanluri meant the suppression of the last Sardinian attempt at independence.

The adoption of Alfonso V of Aragon by the last Angevin queen, Juana II of Naples, gave him justifications to inherit and claim the Neapolitan throne. Supported by the Duchy of Milan, Alfonso conquered the kingdom in 1442, which he bequeathed to his son, his bastard Ferrante, who turned out to be a seasoned ruler.