History of France

The history of France begins in sources written during the Iron Age, when Roman historians called the region Gaul. This was inhabited mainly by the Gauls, people of Celtic origin who did not maintain a political unit, they competed with each other and used writing marginally. The Gauls made several raids outside their original territories, including an invasion of Rome in the IV century BCE. c.

The Roman Republic conquered southern Gaul in the late II century BCE. C. and established the province of Galia Narbonense. Julius Caesar annexed the rest of the region during the Gallic War (58-51 BC). The conquest brought with it a fusion of Celtic and Roman cultures and finally the Romanization of the Gauls and the full integration of the territory within the Roman empire.

In the last years of the Roman Empire, Gaul was the scene of constant incursions by Germanic peoples, among which the Franks would come to dominate the territory from the 17th century V up to the 15th century. The first Frankish dynasty was that of the Merovingians, who with their king Clovis unified Gaul. The second dynasty, the Carolingians, founded in 751, built an empire in western Europe under Charlemagne in the 8th and centuries. style="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">IX. This empire would be divided among his grandchildren in 843 by the Treaty of Verdun, which separated West Francia from East Francia, which would become Germany's ancestor. The third Frankish dynasty, the Capetians, took power in Western Francia from 987. The Capetians, originally with little power over the feudal lords, increased it considerably through their military campaigns and their alliance with the Church. In the 12th century, Philip Augustus was the first to be named "king of France" instead of "king of the Franks". Philip IV (1268-1314), the most powerful Capetian king, achieved dominance over the pope and the Church.

On the death of the last of the direct Capetians in 1328, a succession crisis ensued between the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet. The first acceded to the throne and the second, of French origin but ruler in England, was also a pretender. The crisis led to the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), in which France was devastated. The Plantagenets dominated in the early part of the war, but the Valois managed to prevail in the final phase. In this war, Joan of Arc arose, a peasant teenager who managed to lead the French army and become a national heroine.

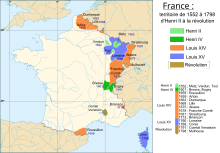

Between the 16th and XVIII, the power of the French kings was consolidated in the Old Regime. In the 16th century came the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation and with the latter, the Wars of Religion (1562-1598), which originated a new succession crisis and the coming to power of the House of Bourbon with Henry IV in 1589. France remained Catholic and the monarchy's alliance with the Church was consolidated. Beginning in the 16th century France began to forge a colonial empire with possessions in North America, the West Indies and India. At the same time, she was involved in numerous wars for hegemony in Europe, mainly against Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, and England. The rise of the Old Regime was reached with the absolutism of Louis XIV, known as the "sun king".

The monarchy was overthrown by the French Revolution (1789-1799), a series of events of universal impact that elevated the bourgeoisie to power and gave prominence to the masses. The first French republic was established in 1792 and the country was attacked by several countries. The first republic was abolished in 1804 with the proclamation of Napoleon Bonaparte as Emperor of France. Napoleon fought against the absolutist monarchies and achieved the submission of a large part of Europe thanks to his great military talent until he was defeated (1815).

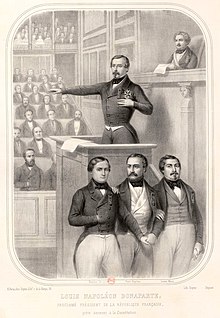

The monarchy returned in 1814, but without the previous privileges. A new revolution broke out in 1830 against what the liberals considered an attempt by the king to restore the Old Regime, and the result was the July Monarchy (1830-1848), a more liberal monarchical government. This increasingly authoritarian government was overthrown in 1848 by a third revolution, which gave way to a brief second republic and served as an example in several European countries. In 1852 President Louis Napoléon Bonaparte established the second French empire. During the 19th century France industrialized and pursued an imperialist policy. The Second Empire was defeated in 1870 by Prussia, a rising German nation and a rival to France. That year a republican system was started again. The third republic, parliamentary, secular and of freedoms, took root in society, at the same time that it conquered a vast colonial territory in Africa and Asia that rivaled the United Kingdom and especially Germany. France agreed with the United Kingdom on the Entente Cordiale, which would later become the Triple Entente with the accession of Russia. France and its allies fought against Germany and the Central Powers during World War I (1914-1918). Much of the war was fought in northern France, which despite being victorious suffered serious economic damage and more than 1.5 million deaths.

In World War II (1939-1945), France was invaded by Nazi Germany. The northern half of the country was occupied by German troops, while the southern half was ruled by the collaborationist Vichy regime. In the colonial empire, General Charles De Gaulle started the Free French movement, which led the resistance against the occupation and fascism. Northern France served as the landing site for numerous Allied armies during the offensive against Germany. France, in critical condition from the devastation, was liberated in August 1944.

After the war, France joined the Western bloc during the Cold War, and has since been part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) as well as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. United (UN). It received significant financial aid from the United States and its economy grew significantly during the thirty glorious years (1946-1975). The fourth republic (1946-1958) tried unsuccessfully to reissue the system of the third, but it was replaced by the fifth republic (1958-present), whose government system is semi-presidential. In 1960 France became the fourth country to develop nuclear weapons. The French colonial empire began to unravel during the Indochina War (1945-1954), the Algerian War (1954-1962), and the subsequent decolonization of its African territories in the 1960s. Its remaining colonies were integrated into departments and collectivities overseas. France was an important cog in the formation of the European Union in 1993. In the 21st century, France is still considered a power in the economic, military, political and cultural aspects.

Prehistory

Tools from the Acheulean industry of Homo erectus from 900,000 years ago have been found in the Le Vallonnet grotto, (Poor Clare's generation) in southern France.

Significant Lower Paleolithic remains exist in the Somme River and traditional Pyrenees (Neanderthal Man), as well as at La Chapelle-aux-Saints, Le Moustier and La Ferrasie. From the Upper Palaeolithic there are abundant remains of the Cro-Magnon, Grimaldi and Chancelade men, dated to about 25,000 years old, which are located in the Dordogne valley. Among the most famous cave paintings in the world are those of Lascaux and Font de Gaume, in the French Pyrenees.

In the Mesolithic, some agricultural activities gradually replaced caves in importance, and in the Neolithic (from the 3rd millennium BC) the megalithic culture emerged (using menhirs, dolmens and burials). From around 1500 B.C. C. the age of the bronze begins, developing commercial routes.

The Iron Age and Celtic cultures date back to the 1st millennium BCE. c.

Protohistory

The first Celts

Although there is little tangible evidence, there is a theory according to which the colonization of the future Gaul by the Celts originally from Central Europe began around 1300 BC. C., at the end of the Bronze Age, with the culture of the urn fields and ended around the year 700 a. Another theory suggests that the earliest Celtic peoples correspond to the archaeological Hallstatt culture (800-400 BC) which developed in Central Europe, including eastern France and corresponds to the early Iron Age. Towards the end of the VIII century B.C. C. iron metallurgy spreads and a warrior aristocracy is constituted thanks to the appearance of iron swords and combat on horseback. Celtic princes and princesses were buried with regalia weapons and chariots, as in the tomb of Vix (550 BC-450 BC), in the Côte-d'Or department.

According to Livy, the abundant warrior populations of the Biturigian, Arverni, Aedui, Ambarro, Carnuti and Aulerc tribes under the command of the legendary Biturigian Beloveso invaded the Po plain and joined the Insubres to found the city of Mediolanum (Milan) around 600 BC. c.

Pre-Roman Gaul (5th century - 51 BC)

Gaul, as defined by Julius Caesar, was the territory where the Gauls lived, and included the present-day territories of France, Belgium, Luxembourg, northern Italy, as well as parts of Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands. The Gallic peoples correspond to the archaeological culture of La Tène, which is considered the apogee of Celtic culture. The Gauls were a conglomerate of Celtic tribes that spoke dialects of a common language, but they did not form a political unit, but rather rivaled each other. In addition to the Gauls, the Romans identified two other peoples: the Aquitanians in the southwest of present-day France, and the Belgians in the northeast.

Celts from regions around the Rhine, the Danube, or the Hercynian Forest extended their authority over the rest of Gaul at the end of the century VI a. C. and beginning of the century V a. C. in the time known as the second iron age or period of the La Tène culture. This new period of expansion corresponds to economic and social transformations. The aristocratic warriors, few in number, were replaced by peasant soldiers regrouped around a clan chief. The iron share plow replaced the wooden plow and made it possible to till the heavy soils of central and northern France today. This largely explains the colonization of new lands, population growth, and the resulting new invasions.

At the beginning of 390 a. C., chief Breno took Gallic warriors (senones, cenómanos, lingones, among others) to northern Italy, where they joined other Celtic peoples (ínsubres, boyos and carnios). Rome was taken in 390 B.C. C. The Romans contained these invaders from the end of 349 a. c.

The Celts began trading with the Greek colonies in southern Gaul as early as the VII century BCE. C. as Massalia (Marseille). This trade was interrupted during the invasions of the 5th century BCE. C. but were vigorously retaken at the end of the IV century B.C. C. During this period, Greek coins are found throughout the Rhone Valley, the Alps, and even in Lorraine.

The Gallic civilization experienced a particularly flourishing period between 290 B.C. C. and 52 a. C. Characteristics of this civilization are the emergence of true fortified cities (oppida) of dimensions much larger than the fortresses of previous periods and the use of currency.

In the II century B.C. C. a relative Arverna hegemony characterized by a strong military power and great wealth of its chiefs is established. At the same time, the Roman influence in southern Gaul increased, which initially manifested itself in the commercial field. Archaeological investigations show that in the course of the II century B.C. C. Italian amphoras gradually replaced those from Greece in the Marseille trade. On several occasions, Marseille went to Rome to defend it from the threats of the Celto-Ligurian tribes and the pressures of the Arverni.

South-eastern Gaul, particularly the present-day regions of Languedoc and Provence, was conquered by Rome before the end of the century II a. C. and formed the Roman province of Galia Narbonense. This region, which ran from the Pyrenees to the Alps and crossed the Rhone Valley, was a strategic territory to unite Italy with Hispania, which had been conquered during the Second Punic War (late III B.C.) The conquest of Narbonne was achieved in 118 B.C. C. after the defeat of the Arverni and Allobroges and the alliance of Rome with the Aedui. After the fall of the Arverna hegemony under the pressure of the Romans, the great peoples of Gaul —particularly Aedui and Sequani— vied strongly among themselves.

In 58 B.C. C., Julius Caesar used the threat that the Germanic peoples represented for the Gauls to intervene in aid of the Aedui, allies of Rome. The Gallic war was long and in January 52 a. C., with the rise to power of Vercingetorix, the Arverni and their allies rebelled against the proconsul's army. Julius Caesar faced the determination of the Gauls, whose uprising was almost general. The war, which included sieges, burning of cities, scorched earth, massacres, and deportations into slavery, ended in 51 BC. C. with the Roman victory against the disorganized impetus of the Gauls.

Old Age

Greek Colonies

About 600 B.C. C., Ionian Greeks from the city of Phocea founded the colony of Massalia (present-day Marseille) on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, making Marseille the oldest city in France. At the same time, some Celtic tribes penetrated the eastern parts of present-day France, but this occupation spread to the rest of France only between the V and III a. c.

Massalia was a prosperous city that founded more cities in the Mediterranean, such as Agathe (Agde), Nikaia (Nice) and Antipolis (Antibes). Pytheas, originally from Massalia, explored northern Europe and reached the Arctic Circle around 325 BC. C. The Greek colonies maintained a lucrative trade with the Gauls, as evidenced by the presence of Greek coins and amphorae in various parts of Gaul. Greek coins influenced the style of Gallic coins, who used the Greek alphabet in what little evidence there is of their writing. The Greek colonies were constantly threatened by the Gallic tribes, so Massalia had to resort to an alliance with Rome. The city lost its independence to the Romans in 49 BC. c.

Roman Gaul

The Emperor Augustus organized Gaul into four provinces: to Narbonensis, sufficiently romanized to become a senatorial province, he added Gaul Aquitaine, Gaul Lyonnaise, and Gaul Belgium. The limits of the Gauls exceeded those of present-day France, mainly as far as Belgian Gaul was concerned, which surrounded the Rhine River. After the conquest of Gaul, the Romans forced displacements of natives to prevent them from becoming a threat, both within of the Gallic provinces as well as outside of them. In addition to the large number of natives, Gaul became the homeland of Roman citizens from other places and of Germanic peoples who migrated to the empire.

Culturally, a syncretism occurred between the Roman culture of the new ruling class and the native Celtic culture, giving rise to the Gallo-Roman culture. Religious practices were a combination of Roman and Celtic, with Celtic gods subject to interpretatio romana. Along with Latin, the Gauls continued to use their language, but switched from the Greek to the Latin alphabet and became considers that their language was used in France until the VI century. Some Celtic influences permeated the culture of the Roman Empire: the caracalla, a cloak that gave a Roman emperor a nickname; the cask, stronger than the Roman amphora, and the coat of mail, the Gallic imperial helmet and braccae, adopted by the Roman army. The Gauls became more and more integrated into the empire. For example, the generals Marco Antonio Primo and Cneo Julio Agrícola and the emperors Claudius and Caracalla were born in Gaul. Also the Emperor Antoninus Pius was from a Gallic family.

The Roman roads largely took over the Gallic roads, which were numerous and in good condition, which explains the great speed of movement of the Roman legions. The pacification of the Rhine and Britain favored the economic boom. Urbanization was widespread and numerous cities developed, organized on the model of the Italian municipia, which still survive, while the countryside was covered with villages (vici) and large farms (villae). Gaul, along with Egypt, was the most populous region of the Roman Empire, with an estimated population of 7 million. In 48, the Emperor Claudius gave access to the Roman Senate to Gaul notables, as shown in the table of Lyons.

Economic development brought about centuries of Pax Romana: vineyards were cultivated in Aquitaine, the Rhône, Saône and Moselle valleys, and Gallic wines competed with Italian wines. In imitation of the terra sigillata itálica, a sealed ceramic industry was created (for example in La Graufesenque). Gallic artisans also produced abundant wooden objects and woolen fabrics that were exported to the great centers of consumption in Italy, the Rhine and the upper Danube. The exchanges were not limited to material goods: in addition to the popular cult of the Gallic religion and its Roman syncretism, which is prohibited by Claudius (41-54), other religions of oriental origin appeared in the cities: the cult of Mithras, of Cibeles and finally Christianity.

Since the II century, there was already an important Christian community in Lugdunum (Lyon), where the first martyrs are from (177) and the first bishopric in Gaul, where Saint Irenaeus would exercise. Christianity, whose origins date back to the Jewish diaspora, spread through the cities thanks to merchants from the East and the army, and after the Edict of Milan spread through the towns, where the emblematic evangelizer is Saint Martin of Tours (316 -397), to whom the founding of monasticism in France is also attributed. Around 250, according to Cyprian of Carthage, Gaul had eight bishoprics (Lyon, Arles, Tolosa, Narbonne, Vienne, Reims, Paris and Trier) and with 120 at the end of the century IV. In 314 the Emperor Constantine convened the first council of Arles, the first held in Gaul.

Five centuries of Romanization left a deep mark on Gaul: languages derived from Latin (Occitan and French), a written law, cities, monumental architecture, the Catholic religion and daily customs, such as the consumption of bread and wine.

Germanic invasions

During the crises of the 3rd century, civil wars broke out on Gallic soil. In the middle of this century, Franks and Alemanni, both Germanic peoples, crossed the Rhine and plundered Gaul on several occasions. General Posthumous created the so-called Gallic Empire (260-274), independent of Rome. Gaul was affected by the Bagauda rebellions that would ravage the entire north of the region from the III century until the V. The Romans allowed the establishment of laeti (barbarian colonies) in Gaul in the IV and V. The defensive systems of the Rhine incorporated more and more Germanic contingents. Groups of Franks in Belgian Gaul and Alemanni in Alsace served as federated auxiliary troops, and certain Frankish officers led brilliant careers in the Roman Empire. A Celtic migration appeared in Armorica in the IV century, consisting of refugees from Britain, who remained independent from the rest of Gaul until 939..

On the night of December 31, 406, Vandals, Suevi, Alans and other Germanic peoples crossed the Rhine border, despite the defense of Frankish auxiliaries. In 412, the Visigoths crossed the Alps and reached Aquitaine. The Roman Empire ceded territories to them until their demise in 476. As the imperial structures fell apart, political power passed into the hands of barbarian kingdoms with their own laws and power. own religion, Arianism or polytheism. The danger posed by the Huns caused a temporary alliance of the occupiers of Gaul. In 451, the patrician and generalissimo Flavio Aecio was put at the head of a Gallo-Roman and Frankish coalition that stopped the incursions of the Huns commanded by Attila in the Catalaunic Fields.

In the midst of various barbarian kingdoms, Aetius was one of the last Roman soldiers to attempt the political reorganization of Gaul, as were the general Egidio and his son Siagrio. Aegidius, in alliance with the Franks, achieved some victories against the Visigoths and the Burgundians and in 457 managed to control militarily a territory between the Seine and the Loire, which history has called "the kingdom of Soissons" a kind of enclave of the Roman Empire that survived its fall. This "kingdom" it would endure with his son Siagrio, who styled himself "king of the Romans," but was finally conquered by Clovis, king of the Franks, in 486. Gallo-Roman noble elites, still present in the cities, maintained the local authority and appointed bishops, who were representatives and protectors of their communities and interlocutors of the Germanic kings and the last representatives of Roman culture. Among these we can mention Avitus of Vienne, Nicetus of Lyon, Remigio de Reims and Gregory of Tours.

Middle Ages

The nation of France only appeared very progressively over the centuries. Some consider that it is only possible to speak of France from the Treaty of Verdun, which would also be the origin of Germany; others that from the accession of Hugo Capeto to power and some others even later. The tradition of primary schools in France traces the origin of the country back to the unification of the Franks, so that today's France is heir to the Frankish kingdom of Clovis, and exists without discontinuity from the year 486 to the present day, where Franks, Burgundians (Burgundians), Vikings (Normans), and also Britons (Bretons), merged with the Gauls in the melting pot that is now called France.

The following dynasties reigned over the territories that made up France in the Middle Ages:

- The Merovingians, descendants of Meroveo and Clodoveo.

- The Carolingians, descendants of Carlos Martel.

- The Capetos, and their secondary branches the Valois and the Bourbons, descendants of Hugo Capeto.

The Merovingians

The kingdom of francs, in Latin Regnum francrumalso known (although less usually) as France (Latin work that did not refer to the present France), or simply the Franco Kingdom, are historiographic denominations that identify the Germanic kingdom of the francs established at the end of the centuryV taking advantage of the decay of Roman authority in the Galias, during the time of so-called barbaric invasions. Merovingia dynasty, the ruler of the francs since the mid-centuryV up to 751, it will establish the largest and most powerful kingdom in Western Europe after the fall of the empire of Theodorico the Great, a state that will exercise control over an extensive territory: the present Belgium, Luxembourg and Switzerland; the almost all of the Netherlands, France and Austria; and the western part of Germany. It was the first lasting dynasty in the territory of today's France.

Of all the tribes in which the francs were divided, were the Psalms—who had settled within the tribes of the limes (frontier) as a federated people occupying the Gaul Belgium—those who managed to eliminate all competition and secure the dominion for their leaders: first, they appear as "rules of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Galia; then, about 509, and headed by Clodoveo I, they had already unified all the French and Romans of the north under their rule; and finally, since their initial establishment in theDiocesis Viennensis and Diocesis Galliarum— previously occupied by other Germanic kingdoms: they defeated the Visigoths in 507 and the Burgundians in 534 and also extended their dominion to Raetia in 537. In Germania, the unromanized villages of alamanes, Bavarians, Turingians and Saxons accepted their dominion.

The dynastic name, in medieval Latin Merovingi or Merohingii ('sons of Meroveo'), it derives from an untested form, similar to the one accredited Merewīowing, of ancient English, being the final «–» a typical Germanic patronymic suffix. The name derives from King Meroveo, to whom many legends surround. Unlike the Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies, the Merovingians never claimed to descend from a god, nor is there evidence that they were considered sacred. The long hair of the Merovingians distinguished them among the Frank peoples, who generally cut their hair. The contemporaries sometimes referred to them as "long haired or scalp earrings" (in Latin reges criniti). A merovingio to whom the hair was cut could not rule, and a rival could be removed from the succession being tonsured and sent to a monastery.

The first known merovingian king was Childerico I (fallen in 481). His son Clodoveo I (r. 481-511), ally with the riparian francs, installed in the rivers Rin and Mosela, was the one who, with his military campaigns, truly enlarged the kingdom between 486 and 507 and joined all the francs, conquering most of the Galia. This expansion was made possible by its conversion to Orthodox Christianity (as opposed to the Arian heresy) and its baptism in Reims towards 496, which led him to the support of the Roman aristocracy and the Western Church. He installed the capital in Paris in 507. At his death the kingdom was divided between his four sons, according to the German custom: Clotary I, was king of Soissons (511-561) (and after Reims (555-561) and the Franks (558-561)); Childebert I, was king of Paris (511-558); Clodomiro, king of Orleans (511-524); and Theodorico I, king of Reims (511-564). The kingdom remained divided, with the exception of four short periods (558-561, 613-623, 629-634, 673-675), to 679. After that, it was only divided once again (717-718). The main divisions of the kingdom give rise to Austrasia, Neustria, Burgundia and Aquitaine.

During the last century of the Merovingian rule, kings, having no more land than to distribute among their warriors, were abandoned by these being increasingly relegated to a ceremonial role. Power will be exercised by the Franciscan aristocracy and above all by the stewards of the palace (major domus), a kind of prime ministers, officials of the highest rank under the king. In 656, Grimoaldom I tried to place his son Childeberto on the throne in Austrasia. Grimoaldo was arrested and executed, but when the Merovingia dynasty was restored his son ruled up to 662. The family of the Pipinosides, originally from Austrasia, took over the stewardships of the palace of Austrasia and later those of Neustria and again placed Provence, Burgundy and Aquitaine, regions then almost independent, within the merovingian orbit and began the conquest of Frisia, north of the kingdom. One of the most famous palace stewards, Carlos Martel, rejected in 732 a Muslim army not far from Poitiers, considered the decisive battle that prevented the conquest of all Europe. To reward his faithful, Martel entrusted immense territories to the Church and redistributed them. This allowed him to ensure the fidelity of his men without getting rid of their own property.

As King Theoderico IV died in 737, Martel was so sure of his power that he continued to rule the kingdoms without the need to proclaim a new king nominal until his death in 741. The dynasty was restored again in 743, but in 751 the son of Charles, Pipino the Breve, deposed the last Merovingian king, Childerico III, to whom he locked up in a convent, and made himself a king among the French warriors. Pipino took the precaution of being crowned in 754 by Pope Stephen II, in the royal abbey of Saint-Denis, an event that provided him with a new legitimacy, that of being chosen by God, inaugurating the caroling dynasty. It will be especially from the imperial coronation of Charlemagne in the year 800, when the usual historiographic denomination of the Frank kingdom will become of Carolingian Empire.

The Carolingians

Pepin the Short, the first Carolingian monarch, conquered the province of Aquitaine, which had become independent, and Septimania, which had become one of the five Muslim provinces of Al-Andalus between 719 and 759. He also intervened outside its borders and conquered Lombard lands, with which he would create the States of the Church, also known as the Papal States or "Patrimonio de San Pedro", as he donated them to the Pope and at the same time declared himself their guarantor. Upon his death, in accordance with Frankish tradition, he divided his kingdom between his two sons, Carloman and Carlos, but Carloman's early death allowed Carlos to reign over a unified Frankish kingdom.. The kingdom of the Franks experienced its greatest expansion during the reign of Carlos, better known as Charlemagne.

Charlemagne extended the borders of the Frankish kingdom, at the cost of twenty years of war, to Saxony, Brittany, Vasconia, Lombardy, Bavaria and the Avar kingdom. However, these conquests would not be definitive and the regions of Brittany and Vasconia were shaken by numerous rebellions. Charlemagne established territories known as "marcas", which were militarized zones that allowed to control the attacks of Bretons and Vascones. This policy of conquest, as well as the support it provided to the papacy, resulted in the coronation of Charlemagne as Roman Emperor on December 25, 800 by Pope Leo III in Saint Peter's Basilica. Until then, the Byzantine emperors were considered the sole heirs of the Roman Empire, so Charlemagne's coronation represented a conflict between the Frankish kingdom and the Byzantine Empire. After the Franks seized Byzantine territory in the Adriatic, Emperor Michael sent delegates to Charlemagne's court in Aachen in 812 to recognize him as Western Emperor. Contemporaries wanted to see in this circumstance the rebirth of the Western Roman Empire. However, the Carolingian empire was centered in the regions of Gaul and Germania and its lineage was of Germanic and not Roman origin.

The reigns of Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious witnessed two waves of invasions, but were also a period of strengthening royal power and a renaissance of arts and culture.

Louis the Pious, emperor between 814 and 840, renounced confiscating the Church's lands to donate them to his faithful as a reward. By doing this, he was forced to use his own assets and thereby weaken the power of the Carolingians. Louis held the empire together, but it would not survive his death. Two of his sons –Carlos el Calvo and Luis el Germánico– allied themselves against his brother Lotario in the oaths of Strasbourg. Finally, the three sons reached an agreement in the treaty of Verdun (843) and the empire was divided into three parts: West Francia for Carlos the Bald, Middle France for Lothair, and East Francia for Louis the German. This is the first time that the name of Gaul is replaced by that of western Francia. Lothair held the title of emperor, but in 869 his kingdom would be divided between his two brothers. In this way, two entities remained as heirs of the old Carolingian empire: Western Francia and Eastern Francia, which would be the germ of present-day France and Germany, respectively. The two Frances were briefly reunited between 884 and 887 under Charles the Fat. On his death, the Frankish kings lost the title of Roman Emperor.

During the IX and X, Western France was threatened with rupture. Brittany, under the leadership of Nominoe, reasserted its independence, and the reincorporation of Aquitaine into the kingdom was nothing more than something purely theoretical. The second wave of invasion by Vikings, Saracens and Hungarians accentuated the disintegration of royal authority. The sovereigns, powerless to defend their territories, resigned themselves to seeing power pass from their hands to those of powerful lords, who constituted principalities, vast semi-independent territories. To curb the Viking threat, King Charles the Simple was forced to cede Normandy to the Viking chieftain Rollo in 911.

The title of king became elective and the Carolingians had to cede the crown to Count Odo of Paris, between 888 and 898, to his brother Robert I between 922 and 923, and to Raul of Burgundy between 923 and 936. In 987 Hugh Capet, Duke of the Franks and descendant of Odo, was preferred as king to the Carolingian pretender Charles of Lower Lotharingia thanks to the active intervention of Archbishop Adalberon of Reims.

The Capetians

The Capetian (or Capetian) dynasty came to rule France, which successively became more and more subdivided, a feature that has been called "classical feudalism". Throughout this period the king had to continually confront the other nobles of his kingdom, in theory his vassals, but who sometimes acquired too much power to openly challenge royal authority. In this period the crusades and the Hundred Years War took place. France invented Gothic art, and there was a time when all of Europe fell victim to the bubonic plague, an epidemic that was called the "black plague". He also participated in humanism that would be a precursor to the Renaissance.

The authority of the early Capetians was limited to their royal domain, confined to an area between Beauvais and Orleans, a remnant of Robert I's duchy of France, while various vassals held much larger possessions. Thanks to a skilful policy of most of them, they were able to ensure the growth of their domains. Faced with their vassals, who were almost independent, the Capetian kings had the following advantages:

- They inherited their lineage by choosing and consecration of their children in life and associating them to the throne, a use that followed up to Philip Augustus.

- They were at the top of the feudal hierarchy and all the feudal lords of the kingdom were to pay tribute to him.

- Real consecration allowed them to acquire a divine right through anointing with the oil of the holy blister, which according to tradition was a gift of the Holy Spirit to the first Frank King, Clodoveo. Thus the king, whose power proceeded directly from God, had the covenant of the Church.

Several regions enjoyed a local authority comparable to that of a kingdom. Several dynasties of French origin even expanded their territories outside of France: the Normans, Plantagenet, Lusignan, Hauteville, Poitiers, and Toulouse. The most important of these conquests was the Norman Conquest of England by William the Conqueror. This event would keep England connected to France for the rest of the Middle Ages and would be a source of conflict between the two kingdoms. The kings of England would be the most powerful vassals of the king of France and would come to aspire to the French throne.

Early Capetians

The founding of the French state began with the election of Hugh Capet in Reims in 987. Capet, until then called "duke of the Franks". he became "king of the Franks". Hugo's territory stretched out in a small area of little relevance that contrasted with the territories of the barons who had elected him. The figure of Hugo Capeto is not well documented in history; His greatest achievement was surviving as king and defeating the Carolingian candidate, allowing him to establish what would become one of the most powerful royal dynasties in Europe centuries later.

Hugh's son, Robert II the Pious, was crowned king before his father's death. Hugh Capet decided so to ensure the succession. Robert II met Emperor Henry II on the border between the two kingdoms. The monarchs agreed to end mutual territorial claims. Although Robert II was a weak king, his efforts were considerable. He relied on the church to rule France to a much greater extent than his father did. Although he lived with a mistress and was excommunicated for it, he was seen as a model of piety; hence the nickname of him, the Pious. From Robert II, miraculous powers were attributed to the kings of France, who could cure scrofula with simple touch. His reign is also remembered for the peace and truce of God (which began in 989) and the Cluniac reform.

During the extraordinarily long reign of Philip I (1060-1108) the kingdom experienced a modest recovery. At this time the first crusade was launched to recover the Holy Land, which had fallen into Saracen hands. This expedition, which culminated in the conquest of Jerusalem and the founding of several Frankish states in the Middle East, involved the king's family, although he was not personally involved.

From the reign of Louis V (1108-1137), royal authority became more widely accepted. Louis VI was above all a warmongering king. His way of raising money by attacking his vassals made him an unpopular king, but on the other hand he strengthened the royal power. From 1127 the king had the assistance of Abbot Suger, an efficient statesman. Louis VI defeated many of his vassals both militarily and politically. He frequently called them to court and those who did not attend had their territories confiscated and military campaigns launched against them. This drastic policy imposed some royal authority in Paris and the surrounding areas. When Louis VI died in 1137 he had done quite a bit to strengthen the authority of the Capetians.

Thanks to the political advice of Abbot Suger, Louis VII (1131-1180) enjoyed greater moral authority than his predecessors. Abbot Suger arranged for Louis VII's marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, which took place in 1137. This made Louis VII Duke of Aquitaine and gave him considerable power. However, tensions soon surfaced in the couple. Through Eleanor's influence, the king went to war against the count of Champagne, a conflict in which more than a thousand people were burned alive in Vitry. The king, sorry for the event, did penance and traveled to the Holy Land. Later, he involved the kingdom of France in the second crusade, but his relationship with Eleanor did not improve. Her marriage was annulled by the pope, and Eleanor soon married Henry Fitzempress, Duke of Normandy. Louis VII now faced a much more powerful vassal than he, as Henry was the largest feudatory of France, holding Normandy and Aquitaine, and in 1154 he became King Henry II of England.

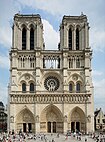

Abbot Suger was the architect of Gothic architecture, born in northern France, particularly in the Île-de-France and Picardy regions. This style, which spread, would be the standard for most European cathedrals in the Late Middle Ages.

Philip II Augustus

The reign of Philip II Augustus (1179-1223) was an important step in the history of the French monarchy, witnessing the expansion of royal power and influence. He laid the foundation for the rise of far more powerful monarchs, such as Saint Louis and Philip the Beautiful.

Philip II spent a significant part of his reign fighting the Angevin Empire, which included England and half the kingdom of France and was perhaps the greatest threat to a French king since the rise of the Capetian dynasty. Philip II allied with Richard the Lionheart against his father, Henry II of England, and together they launched a decisive attack on Henry's castle at Chinon and removed him from power. Richard replaced his father as King of England. Felipe and Ricardo fought together in the third crusade; however, their alliance and friendship broke down during the crusade. The two kings later clashed in France, and Richard came close to defeating Philip II.

In addition to their battles in France, both kings attempted to place their respective allies on the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. Philip II supported Philip of Swabia, of the House of Hohenstaufen, while Richard the Lionheart supported Otto IV, a member of the House of Welf. Otto IV crowned himself emperor, which meant a great danger for Felipe. The crown of France was saved thanks to Richard's death during a battle in the Limousin.

Philip II confiscated the possessions of Juan sin Tierra, Ricardo's successor, in France. John attempted to recover his possessions at the Battle of Bouvines (1214), where he was defeated. Felipe II was then able to annex Normandy and Anjou, in addition to capturing the counts of Boulogne and Flanders, although Aquitaine and Gascony remained faithful to the King of England. Following the Battle of Bouvines, John's ally Otto IV was overthrown from the Holy Roman Empire by Frederick II, an ally of Philip Augustus. The King of France has since played a crucial role in Western European politics in both England and France.

Philip Augustus founded the Sorbonne University and turned Paris into a city of learning. He also expanded the city walls, paved the roads, and built the Louvre castle.

Prince Louis (later Louis VIII, 1223-1226), became involved in the English civil war known as the First Barons' War (1215-1217). While the kings of France faced the Plantagenets both in France and abroad, the Church summoned them to the Albigensian crusade against the Cathars, a Christian movement rooted in southern France that was considered heretical. The war, which was fought between 1209 and 1244, ended with the eradication of Catharism and the expansion of royal domains in the south.

Saint Louis

Louis IX, known as Saint Louis, was only twelve years old when he became King of France. His mother, Blanca de Castilla, exercised power as regent. Blanca's authority met with strong opposition from the French barons, but she managed to stay in power until her son was able to rule for himself.

Under Louis IX, France became a centralized kingdom. St. Louis has often been seen as a representative of the Catholic faith and a reformer concerned with his government. However, his reign was far from perfect. In 1229, the king fought a strike at the University of Paris, causing damage to the city's Latin Quarter. Saint Louis also fought a war against the County of Tolosa and fought the resistance in Languedoc. Count Raymond VII of Toulouse signed the Treaty of Paris in 1229. His daughter, Juana, had no heirs, so the county passed into the hands of the King of France. King Henry III of England did not recognize the Capetian possession of Aquitaine and hoped to recapture Normandy and Anjou to restore the Angevin Empire. He landed in 1230 at Saint-Malo with a large army. Brittany and Normandy immediately surrendered. This English invasion evolved into the Saintonge War (1242). Finally, Henry III was defeated and had to recognize French rule, although the King of France could not take Aquitaine. Louis IX, in addition to holding the royal title, became the largest land owner in France, although he faced some opposition in Normandy. In those times the King's Council was founded, which would later become the parliament. After the conflict with the King of England, both established a cordial relationship.

San Luis was a patron of Gothic art. During his reign, the Holy Chapel of Paris was built, one of the masterpieces of radiant Gothic. He is also credited with the Morgan Bible. Saint Louis participated in two crusades. In the seventh crusade (1248-1250) he attacked Egypt and managed to conquer the city of Damietta, but was defeated and taken prisoner at Fariskur in 1250. The eighth crusade was launched against Tunis in 1270, where the French king died of illness that same anus.

Philip III and Philip IV

Philip III ascended to the throne on the death of Saint Louis in 1270. He was called "the daring" in reference to his skills in combat and horsemanship and not precisely because of his ability to govern or his temperament. Philip III took part in yet another Crusader disaster: the Aragonese Crusade, which cost him his life in 1285.

Philip IV (1285-1314) made several administrative reforms. He was responsible for the suppression of the Knights Templar, signed the Old Alliance with Scotland, and established the Parliament of Paris. Philip IV, unlike the early Capetians, was so powerful that he was able to appoint popes and emperors. The papal seat was transferred to Avignon and all contemporary popes were French.

The three male children of Philip IV who reached adulthood reigned in short successive periods between 1314 and 1328. None of his children had male children, so in 1328 the direct Capetian house became extinct.

The first Valois and the Hundred Years War

On the death of Charles IV, the last king of the direct childless Capetian house in 1328, there were two claimants to the French throne: Edward III of England, grandson of Philip IV of France, and Philip of Valois, grandson of Philip III of France. The assembly of notables of the kingdom chose Philip of Valois (Philip VI) because he was French, descended from the Capetians through the male route, and was older than his young English rival. Philip VI was the first king of the House of Valois, a collateral branch of the Capetians who would reign in France until 1589.

Tensions between the Plantagenet and Valois houses reached their peak in the so-called Hundred Years' War (actually a series of several armed conflicts between 1337 and 1453), in which the Plantagenets, rulers in England, claimed for himself the French throne. The war began when Edward III of England, Duke of Guyenne, invaded France through Flanders in 1337.

The war did not develop throughout the country, but wherever it occurred it brought desolation, death, looting, civil wars and epidemics. The bands of mercenaries, in the absence of a military quartermaster and a regular salary, looted the regions where they were stationed. During this interminable conflict, French territory was the field of fierce fighting between the kings of France and those of England. The English benefited from the tactical superiority of their army, particularly their archers, and inflicted two resounding defeats on the French cavalry – far superior in number – at Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356); in the latter King John II of France was taken prisoner by the black prince, Edward of Woodstock. The Dauphin Charles was forced to sign the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360, in which he granted the English a third of the kingdom of France and promised to pay a ransom of 3 million escudos – the equivalent of two years' royal income. – for the release of the king. He died in London in 1364 without the ransom having been paid in full.

Carlos V, son of Juan II, was a good strategist: peace allowed him to reconquer the ceded territories and entrusted great captains, such as Du Guesclin, with the reconquest of the territory, retaking the strongholds of the enemy one by one through a strategy of successive sieges. In 1377 the English controlled only Bayonne, Bordeaux, Brest, Calais and Cherbourg.

Recovery was provisional. The madness of Charles VI plunged the country into civil war between Philip II of Burgundy, the King's uncle, and Louis of Orleans, the King's brother. The latter took control of the State and allied himself with gentlemen from the southwest hostile to the King of England, known as the Armagnacs, who would fight the Burgundians. The Duke of Burgundy, also Count of Flanders, traded with the English in that region.

Taking advantage of the confusion of the civil war, the English launched a devastating chevauchée across France. After avoiding Paris they crossed Picardy to the port of Calais and met up at Azincourt with the cream of French cavalry in 1415. The French suffered another devastating defeat against a tired and outnumbered English army. Armagnacs were crushed. The Duke of Burgundy, Juan Fearless, took advantage of the situation to seize Champagne and later Paris. His son, Felipe el Bueno, forced King Carlos VI to sign the Treaty of Troyes on May 21, 1420, which stipulated: that the king's son, the dauphin Carlos, was disinherited; Henry V of England became regent of France and would marry Catherine, the daughter of the French king, and on the death of Charles VI, the kingdom of France would pass to the son of Henry V and Catherine.

On the death of Charles VI in 1422, France was divided into three: the north and the west under the control of Henry V's brother, John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford, as regent for the young English king, the future Henry VI; the northeast, where the Duke of Burgundy was semi-independent, and the region south of the Loire, where the dauphin takes the title of Charles VII, whose legitimacy is questioned by English propaganda.

The key to the conflict is then the nationalist awakening in the face of the suffering of the French people. The English, with their looting strategy, received the hatred of the people and were only supported by artisans and university students from the big cities. That nationalism would be embodied by Joan of Arc, a young peasant girl who would catalyze the desire to drive the English out of France by receiving command of the military campaigns. After a victorious campaign on the Loire, Joan liberated Orleans and crushed the English at the Battle of Patay. Later he rode to Reims, where he achieved the coronation of Charles VII on July 17, 1429. During the winter of 1429, Joan seized the town of Saint-Pierre-le-Moûtier, but failed in the village of La Charité-sur- Loire before being captured in Compiègne on March 24, 1430. The end of the conflict was near: Carlos VII sealed peace with the Burgundians in 1435 through the treaty of Arras. Deprived of their powerful ally, the English are expelled from France in 1453 after the Battle of Castillon.

After the war, the kings of France regained their prestige and authority. However, they maintained a rivalry with the dukes of Burgundy Philip the Good and Charles the Bold, who incorporated the Netherlands into their possessions and ranked among the most powerful sovereigns in Europe. On the death of the Bold, his possessions, which came from the Capetian family, were annexed by Louis XI, but the Netherlands passed into the hands of his daughter, Maria de Borgoña, who gave them to her husband Maximilian of Austria.. This partition of the Burgundian possessions was a source of conflict between the houses of France and Austria.

The Middle Ages ended with the end of the independence of the great principalities that were the Duchy of Burgundy (1482) and the Duchy of Brittany (defeated in 1488, reincorporated in 1491 and formally united to the kingdom in 1532).

Modern Age

Affirmation of royal power

From the end of the 15th century to the middle of the XVI, French foreign policy was dominated mainly by the wars in Italy. The Valois sought to assert the rights inherited from their ancestors over the Kingdom of Naples and the Duchy of Milan. In 60 years, the Valois conquered and lost Naples four times and the duchy of Milan six times. Ultimately, they abandoned their ambitions in Italy. There are several explanations for the usefulness of these expeditions that inevitably ended in failure, including the lure of the wealth and culture of prestigious Italian cities, as well as the desire to control routes that would threaten Habsburg interests in the south. In the 16th century, military strategies focused on the idea of the offensive frontier, which consisted of occupying support points to prevent the advance of the enemy rather than expand the territory of the kingdom.

In 1519, Carlos I, King of Spain since 1516, inherited the possessions of the Habsburgs (Austrian Empire, Netherlands, Franche-Comté). France was the obstacle to overcome to territorially unify her territories. The emperor also had inexhaustible reserves of gold and silver from the Spanish colonies in America. Francis I of France ran for election to the Holy Roman Empire in vain to limit Habsburg influence and also failed to forge an alliance with Henry VIII of England. Beginning in 1521, France went to war long and difficult in Italy, which began with the disaster of Pavia in February 1525, where Francis I was taken prisoner. The king was forced to sign the Treaty of Madrid in 1526, which amputated a third of the territory of France, but resumed the war once released. In 1529, in the peace of Cambrai, he relinquished the sovereignty of Flanders and Artois, two possessions of Charles V, while he renounced Burgundy. Although he fought the Protestant Reformation in his kingdom, Francis I allied himself with the German Protestant princes and even the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Suleiman the Magnificent, against the Habsburgs. Henry II continued his father's fight, and recaptured Boulonnais and pale de Calais from the English. In exchange for his support of the German Protestant princes, at war with Emperor Charles V, he obtained the right to occupy Calais, Metz, Toul, and Verdun. In 1559, the treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis finally established peace between France and Spain.

In the 16th century warfare was considerably transformed. Artillery, whose role was decisive in naval battles and sieges, began to be used in combat in the open field. France, in order to retain its power in the European game, not only had to maintain a standing army (the compagnies d'ordonnance created by Charles VII), but also possess solid artillery and build fortresses capable of to resist the new techniques of warfare.

The Italian Renaissance reached France through the Italian Wars. Francis I brought Leonardo da Vinci to his court. The Loire castles were built at this time: Blois, Chambord, Chenonceau and Montsoreau. French sculpture, painting and architecture are transformed under the influence of the Italian model and give rise to the French Renaissance, whose most recognized school would be the from Fontainebleau school. Francis I was the first king of France to understand that the artistic splendor of a country is an element of glory and power. Understanding the importance of colonial possessions, Francisco I financed distant expeditions. In 1534 the Breton Jacques Cartier discovered New France, which would later become Canada.

All of the above cost quite dearly. The size (tax) multiplied four times throughout the XVI century, going from 5 to 20 million pounds. However, fiscal resources were insufficient to finance the expenses. The kings of France resorted to loans –the debt doubled between 1522 and 1550–; to bankruptcy in 1558 and 1567, which made it possible to cancel certain debts, but above all to renegotiate payments, and the venality of charges. A position was a public function whose holders were immovable from 1467 and were sold in the name of the king. Although venality had existed since the 15th century, Louis XII and Francis I developed it systematically. With venality, the official inheritance was established little by little with the creation of the paulette in 1604, an annual tax that was 1/60 of the purchase value of the charge. The advantages were obvious in providing kings with quick inflows of money, but there were also drawbacks.

During the reign of Francis I, Auvergne was definitively incorporated into the royal domain. Henry IV acquired Bresse, Bugey, the country of Gex, which placed him in a position to interfere with communications between the Habsburg possessions. At first, he refused to unite his personal fiefs to the crown under the pretext of preserving the interests of his sister. The Parliament of Paris refused, in 1590, to register the letters that separated the patrimonial assets of the Navarre family and the royal domain. After the death of his sister, Henry IV accepted the integration of his fiefs into the royal domain. Also in the XVI century, the theory of the inalienability of royal domain was forged: the king could not give fiefdoms to the his minor children.

The Wars of Religion

The reigns of the three sons of Henry II, Francis II (1559-1560), Charles IX (1560-1574) and Henry III (1574-1589) were marked by religious wars between Protestants and Catholics. The reform had spread progressively in France from 1520, to the point that in 1562, the year the eight wars of religion began, one tenth of the population was Protestant. Calvinism, whose followers in France were called Huguenots, had their main strongholds in Normandy and the southwest of the country.

Henry II's sons were weak kings, and the widowed queen Catherine de' Medici assumed power as regent for the first two. She is credited with instigating the Saint Bartholomew massacre on August 24, 1572, and the following days, when Protestants were attacked in their own homes, resulting in several thousand casualties in Paris and the provinces. The civil war was also a great threat to territorial unity. The Protestants promised Elizabeth I of England to restore the Calais pale in exchange for her intervention, while the reaction of the Catholics, led by the Catholic League, obtained the support of Philip II of Spain. In addition, the agitation allowed the parties involved to arrogate parcels of the State's royalties. The Catholic princes were very powerful in the regions where they obtained the government, such as the Guises in Burgundy and the Montmorency in Languedoc. Beaulieu's edict of 1576 allowed Protestants to worship publicly except in Paris. They were able to occupy eight strongholds and benefited from parity chambers (chambres mi-parties, courts of justice with half Protestant and half Catholic magistrates) in parliaments. The Protestants were thus able to establish a Huguenot state within the French state.

The religious wars ended with the War of the Three Henrys. Duke Henry I of Guise, head of the Catholic League, confronted King Henry III over his agreements with the Huguenots. The power of Guise, an ally of Spain and with strong popular support, became a threat to the king, who ordered his assassination in 1588. In retaliation, the monk Jacques Clément assassinated the king six months later. The throne, without an heir from the Valois branch, then passed to a collateral branch, the Bourbons, in the person of Henry IV, once King of Navarre. However, being a Protestant, Henry IV was not recognized by the Catholics of the League, so he had to convert to Catholicism in 1593.

Consolidating his power, Henry IV put an end to the religious wars by promulgating the Edict of Nantes in 1598, which recognized Catholicism as the official religion of France, but granted civil rights and privileges to the protestants. Helped by his minister Sully, Henry IV strove to rebuild the kingdom, hard hit by the wars of religion. When Henry IV was assassinated by a fanatical Catholic in 1610, he bequeathed to his son Louis XIII a considerably strengthened kingdom.

The Great Century

Grand Century (Grand Siècle) refers to the XVII century, which constitutes one one of the richest periods in the history of France. With the end of the wars of religion, royal authority was reestablished. During this period, marked by absolute monarchy, the kingdom of France marked Europe in a lasting way thanks to its military expansion or its increasingly dominant cultural influence. The French language, art, fashion and literature spread throughout Europe.

Louis XIII

Louis XIII was only nine years old when his father Henry IV was assassinated in 1610. His mother, Marie de' Medici, ruled with her favorites and neglected the young king's education. Louis XIII removed his mother from power in 1617 by assassinating his favorite Concini. From 1624, Louis XIII reigned closely with his chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu, whom he supports against the intrigues of the nobles, who resented being excluded from power. Louis XIII led a policy of taming the great lords of the kingdom (for example, the affair of the Count of Chalais in 1626), of hardening towards the Protestants, from whom he managed to snatch the strongholds that the Edict of Nantes had granted them. He installed administrations of justice, police and finance in the provinces. Unlike the officers, the intendants had revocable charges. They were indispensable in border regions or in French-occupied areas, and they ensured order by fighting looting by French soldiers and winning the allegiance of nobles and cities. The king accentuated centralization by favoring the minting shop in Paris to the detriment of those in the provinces.

In 1620 religious conflicts continued. The Huguenots proclaimed a constitution for the "Republic of the Reformed Churches of France" and Minister Richelieu used all the force of the State to stop them. He forced the Protestants to dismantle their army and forts. This conflict ended with the siege of La Rochelle (1627-1628), in which the Huguenots and their English allies were defeated. The 1629 Peace of Alais confirmed religious freedom but dismantled the Huguenot military defenses.

Since 1635, Louis XIII and Cardinal de Richelieu entered the Thirty Years' War alongside the German Protestant princes in order to reduce the power of the Habsburgs, both in Spain, the leading European power at the time, as in Austria, the head of the Holy Roman Empire. To weaken the Habsburgs, the French occupied strongholds and secured the passes that connected them with their allies in Alsace, Lorraine, and Piedmont. The considerable increase in tax pressure due to the war led to numerous popular uprisings, such as the Saintonge-Périgord crocantes (1636-1637) and the Normandy va-nu-pieds (1639), severely suppressed.

Louis XIV

When Louis XIII died in 1643, his son Louis XIV was four years old. His mother Anne of Austria assumed the regency together with Cardinal Mazarin. The latter is the one who governed effectively until 1661, the date of his death, even after Louis XIV came of age. Mazarin continued the war effort started by Richelieu. French troops won decisive victories that brought the Thirty Years' War to an end in 1648. The Treaty of Münster of 1648 gave France almost all of Alsace, confirmed possession of the three bishoprics, and granted it three fortresses on the right bank of the Rhine: Landau, Philippsburg and Breisach. Mazarin also continued the policy of controlling the passes to the Holy Roman Empire. The conflict would continue with Spain until 1659. With the peace of the Pyrenees, the royal domain was extended with the acquisition of Roussillon, Artois and certain places in Hainaut, such as Thionville and Montmédy, the Pyrenees were established as the border between France and Spain and Louis XIV married the Spanish Infanta Maria Teresa of Austria. During the king's minority, the Fronde (1648-1653) took place, a series of rebellions caused by increased taxes that turned the government against princes, courts and most of the people. The Fronde was the last attempt by the nobility to counter the king's power, and its failure further strengthened the monarchy.

On Mazarin's death in 1661, Louis XIV declared that he would rule alone, that is, without a prime minister. He demanded strict obedience from his secretaries of state and forbade them to decide without him. To ensure the obedience of his ministers, he chose them from among the bourgeoisie, as is the case with Colbert and Le Tellier. The reign of Louis XIV marked an extreme centralization of royal power. The big decisions were taken by the superior council, which met two or three times a week and had no more than 3 to 5 ministers. The intendants became more than ever the voice of the king in the provinces. From the beginning of his personal reign in 1661, Louis XIV reinstated royal authority. The governors of the provinces, coming from the high nobility, no longer had an army at their disposal and had to reside in the courts, which made clientelism more difficult. With Colbert, the king undertook a judicial reform and had a series of ordinances or codes applicable throughout the kingdom drawn up. Not being sure of the fidelity of the officers who had hereditary charges, the king entrusted their functions to commissioners with revocable charges. This procedure ended up forcing the officials to obey the king. The nobility lost all political power and their main concern since then was to be noticed by the king. To do this, he had to spend excessively and request pensions from the king to ensure his lavish lifestyle.

Louis XIV believed that war was the natural vocation of a king. However, at the beginning of his reign the army was still a private enterprise monopolized by the nobility. Under Le Tellier and after Louvois, officers were controlled by civil administrators who applied strict regulations and stripped them of much of their power. Efforts to modernize and discipline the army enabled Louis XIV to win important victories in the early part of his personal reign. The War of Devolution (1667-1668) allowed him to conquer new strongholds in northern France, such as Dunkirk, Lille and Douai. The Treaties of Nijmegen in 1678 ended the Franco-Dutch War. Louis XIV was unable to defeat the Netherlands, but acquired the Franche-Comté of Spain. Through exchanges of strongholds, the northern border was regularized. In the years 1680 and 1681 Louis XIV carried out a & # 34; meeting policy & # 34;, through which he took over the rural areas that surrounded the strongholds acquired in treaties with other countries. During the period of peace, he annexed, among others, Nancy and Strasbourg. This policy involved France in two conflicts. After the War of the Reunions (1684-1685), France won Luxembourg from Spain and Strasbourg from the Holy Empire. The War of the League of Augsburg (1688-1697) confirmed French possession of Alsace, but France had to evacuate Luxembourg, Catalonia and the Palatinate.

On October 22, 1685, by the Edict of Fontainebleau, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes of 1598. Protestantism was outlawed in France, its churches and schools were destroyed, and its faithful had to convert to Catholicism or emigrate. Between 140,000 and 160,000 chose this option.

In 1701 the War of the Spanish Succession began. Louis XIV's grandson, Philip of Anjou, was designated heir to the Spanish throne as Philip V. Emperor Leopold opposed the Bourbons' extension of their power in Europe and claimed the Spanish throne for himself. Leopold counted on the alliance of England and the United Provinces of the Netherlands. The allies were victorious at the Battle of Blenheim (1704) and had some Pyrrhic victories at the bloody battles of Ramillies (1706) and Malplaquet (1709), where they lost too many men to continue the war. Commanded by Villars, the French recovered in battles such as Denain (1712). Finally, an agreement was reached with the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713. Philip of Anjou was confirmed as Philip V of Spain, but he renounced the throne of France.

The Age of Enlightenment

Louis XV

Louis XV reigned from 1715 to 1774. Having been five years old on the death of his great-grandfather Louis XIV, power was entrusted to a regency council led by Duke Philippe II of Orleans. This made the parliament of Paris annul the testament of the late king, which limited his power. In exchange, he restored to Parliament the right of reprimand, a power that Louis XIV had withdrawn from it and which Parliament would use throughout the XVIIIth century as a means of challenging the monarchy. The era was marked by the relaxation of morale, the economic boom and speculation. The taste for exotic products favored the development of Atlantic ports. Colonial product merchants, the monarchy, and slave traders made great fortunes, and colonists imported products made in France. At this time the port of Nantes developed and slave traders built imposing buildings in Nantes, Bordeaux and La Rochelle. Under the regency of the Duke of Orleans, France entered the War of the Quadruple Alliance against Spain. Philip V of Spain withdrew from the conflict, confronted with the reality that Spain was no longer a great power in Europe.

When the regent died in 1723, Louis XV relied on one of his ministers, Fleury, his former tutor and in whom he had complete confidence, until his death in 1743, the date on which the king took over the reins power. In his reign, France expanded. In 1735, after the War of the Polish Succession, Lorraine, a sovereign principality occupied several times by France, was donated to Stanislaus Leszczyński, father-in-law of Louis XV who had been expelled from the Polish throne by Russia and Austria. On his death in 1766, Lorraine entered the royal domain. Corsica, de facto independent since 1755, was symbolically ceded to France by the Republic of Genoa in 1768 and then subjugated militarily after the Battle of Ponte Nuovo in May 1769. Years earlier, in 1762, the Dombes region had also joined the royal domain. During the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI, a policy of simplification and regularization of the borders was carried out, with which places were exchanged with neighboring states to avoid French exclaves outside the borders and foreign enclaves in France. In 1789 there were only three foreign enclaves on French territory: Avignon and the Venetian County, which belonged to the pope, the principality of Montbéliard and the republic of Mulhouse.

In the 18th century the theory of France's natural borders was forged: the Atlantic Ocean, the Pyrenees, the Mediterranean, the Alps, the Meuse and the Rhine. However, this theory does not seem to have been the official doctrine of the State at that time, since Louis XV rejected the annexation of the Austrian Netherlands (present-day Belgium) several times, which remained within those limits.

In 1740, the War of the Austrian Succession broke out. The war raged in North America, India, and Europe, and inconclusive terms were agreed upon in the Treaty of Aachen (1748). Prussia was becoming a threat, since she had gained substantial territory at the expense of Austria. This led to the diplomatic revolution of 1756, in which the alliances of the previous war were mostly reversed. France was now allied with Austria and Russia, while Great Britain was allied with Prussia. This end of the conflict was not seen as a peace, but as a mere truce.

The Seven Years' War (1756-1763) pitted France against Great Britain. In North America, France had some temporary successes in alliance with various Amerindian peoples, but was defeated at the Battle of Quebec. In Europe, he tried in vain several times to subdue Hannover, and with her allies Russia and Austria he was about to destroy Prussia, but the Anglo-Prussian alliance was saved by the miracle of the House of Brandenburg. At sea, France suffered defeats at Lagos and Quiberon Bay in 1759, and a blockade forced French ships to remain in port. Peace was concluded in the Treaty of Paris (1763) in which France lost its empire with the loss of New France and India, where it only kept Yanaon, Chandernagor, Karikal, Mahé and Pondicherry, against its rival Great Britain.

The state's biggest problem is the chronic budget deficit, which makes the king dependent on financiers and money managers. Another source of paralysis was the opposition of the parliament, which is positioned as defender of the laws of the kingdom and as a counterbalancing power. By opposing any attempt to reform the kingdom, Parliament contributed to the crisis of the absolute monarchy during the reign of Louis XVI.

Louis XVI

Louis XV's grandson, Louis XVI, came to power in 1774. Shy by nature, he lived at a court permeated by intrigue and cabals. His reign was marked by fickle politics. Faced with pressure from the court, parliaments and the nobility, the king is incapable of taking the necessary measures to remedy an excessive public debt and budget deficit.

Having lost its colonial empire, France saw an opportunity to exact revenge on Great Britain by making an alliance with the Americans in 1778 and sending an army and navy to the Thirteen Colonies. Admiral Grasse defeated a British fleet in the Chesapeake Bay while the Comte de Rochambeau and the Marquis de Lafayette joined American forces in defeating the British at Yorktown. The war ended with the Treaty of Paris (1783) and American independence, but with large debts for France.

Despite attempts at administrative centralization, the country was not unified. There were internal customs between the provinces and there was no unit of weights and measures. All this hampered the economic development of France at a time when England was in full industrial boom. Taxes were not collected in the same way throughout the country, even when the mayors supervised the distribution and collection. Despite the efforts undertaken by Francisco I with the Villers-Cotterêts ordinance, the laws were not the same throughout the kingdom. The north was still governed by customary law (uses and customs), with just over 300 customs, while the south was governed by written law, inspired by Roman law. The Old Regime had the custom not to suppress anything, but to superimpose. In this way, in the 1780s there was a tangle of circumscriptions with different sizes and functions: dioceses of Antiquity, bailiwicks and stewards of the Middle Ages and generalities of the century XVI. For example, an inhabitant of Saint Mesnin resided in the bailiwick of Semur, paid his taxes at the Semur tax office, and was subject to the sub-delegate of Vitteaux and the Bishop of Dijon. If he had any business with waters or forests, he should go to Avallon; if he needed consular justice, his trip would take him to Saulieu. This confusion is explained by the manner in which the royal domain was formed. With each acquisition, the kings promised to respect the privileges and customs of the provinces and cities. At the dawn of the revolution, regional particularities were still very much alive.

The French Enlightenment

From the end of the XVIII century and throughout the following France would be the epicenter of intellectual trends known under the term of the Enlightenment, the prelude to the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution.

The "philosophers" they were French intellectuals who dominated the French Enlightenment and were influential throughout Europe. Their interests were diverse, and there were experts in science, literature, philosophy, and sociology. His goal was human progress. Concentrating on social and material sciences, they believed that a rational society was the only logical outcome of a free-thinking and congruent population. They also defended deism and religious tolerance. Many believed that religion had been a source of conflict since time immemorial and that logical and rational thought was the way forward for humanity.

In the first half of the 18th century the movement was dominated by Voltaire and Montesquieu, but the movement grew as the century progressed. In general, philosophers were inspired by the thoughts of René Descartes, the skepticism of the libertines and the popularization of science by Bernard de Fontenelle. Sectarian dissensions within the church, the gradual weakening of the absolute monarch, and Louis XIV's numerous wars allowed his influence to spread throughout Europe, in what is known as enlightened despotism. Between 1748 and 1751 the philosophers reached their most influential period, with Montesquieu (The Spirit of Laws, 1748) and Jean Jacques Rousseau (Discourse on the moral effects of arts and sciences, 1750).

The philosopher Denis Diderot was the chief editor of one of the greatest achievements of the Enlightenment, the Encyclopedia (1751-1752), a reference work with 72,000 articles that sparked a revolution in the Learning in the Enlightenment World.

Contemporary Age

French Revolution

It was a social and political process that took place between 1789 and 1799 whose main consequences were the abolition of the absolute monarchy and the proclamation of the Republic, eliminating the economic and social bases of the Old Regime. Although the political organization of France oscillated between republic, empire and monarchy for 75 years after the First Republic fell after Napoleon's coup, the truth is that the revolution marked the definitive end of absolutism and gave birth to a new regime where the citizenry, and sometimes the popular masses, became the dominant political force in the country.

National Assembly and Constituent Assembly (1789-1791)

Unable to establish a universal tax, Louis XVI convened the Estates General on 5 May 1789 at Versailles. The Third Estate managed to have double representation, but their votes were not double counted. Due to this situation, the third estate broke with the Estates General and with the support of some members of the clergy and the nobility decided to establish itself as the National Assembly, a legislative body erected as the representative of the nation.

Louis XVI closed the Estates room, in an attempt to prevent the Assembly from meeting. This, with the support of some members of the nobility and the clergy, managed to meet and proclaim the oath of the ball game in a nearby building in Versailles, on June 20, 1789, in which its members swore to stay together until endowing the kingdom. of a constitution. On July 9, the Assembly adopted the name of the National Constituent Assembly.

Faced with political instability and economic crisis, Paris fell into anarchy. The concentration of royal troops in Versailles, Paris and the surrounding area, and the dismissal of the economy minister Necker for having supported the Assembly raised fears that a coup d'état was being prepared. The Parisian voters met on July 13 to form bourgeois militias, whose symbol was the bicolor cockade, the traditional colors of Paris. The next day, July 14, 1789, the insurgents, supported by these militias, launched to take the Bastille prison, which served as a depot for weapons and ammunition and at the same time was a symbol of monarchical tyranny. This event is celebrated every year as the national holiday of France. The insurgents then targeted the Paris City Hall and executed its ruler, Jacques de Flesselles.

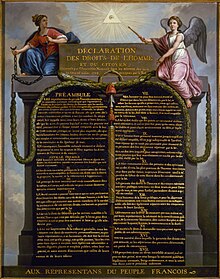

On July 15, Bailly, then president of the Assembly, is appointed the first mayor of Paris under a new government structure known as the Paris Commune. The bourgeois militias change their name to the National Guard, whose commander is Lafayette. The king accepted the new order born of the revolution when he visited the Assembly on July 16, 1789, and the following day the Paris City Hall, where he agreed to wear the cockade bicolor. On July 27, the bicolor cockade was changed to tricolor at the proposal of Lafayette, where the white stripe represented the king. This would be the antecedent of the flag of France. Despite peace being reached between the king and the insurgents, violent peasant rebellions called "the great fear" broke out in the interior of the country. In addition, various members of the nobility, the clergy and even the bourgeoisie Unwilling to accept the changes, they went abroad in search of support to fight the revolution: they are called émigrés. In August, the Assembly published several decrees, among which the recognition of the king and the abolition of privileges stand out., feudalism, serfdom and tithing, as well as the declaration of the rights of man and the citizen. In October 1789 a crowd led by women marched on the Palace of Versailles to protest the shortage of bread; after which the royal family and the Assembly were forced to settle in the Tuileries Palace in Paris.