History of Equatorial Guinea

The history of Equatorial Guinea is based on the roots of loosely organized medieval tribal kingdoms, which arose from the influence of more advanced proto-state structures that developed in parallel in the area: the Oyo Empire, the Kingdom of Dahomey, the Kingdom of Benin, the Kingdom of Loango, the Kingdom of Congo, the Benga kingdom of Mandj Island (later called Corisco), the organization of the Bubi clans on the island of Bioko, and the villa-states of the mainland fang clans.

There is a possibility that the Gulf of Guinea area was visited by Hanno the Navigator, a Carthaginian general who made a voyage along the coast of Africa towards the end of the 6th century B.C. C. or beginning of the 5th century B.C. c.

Pre-colonial period

Río Muni ethnic groups

The continental part of the territory of Equatorial Guinea, known as Río Muni (Mbini), and currently divided into 4 provinces (Litoral, Centro Sur, Kié-Ntem and Wele-Nzas) was populated from times much older than the islands. All the known historical peoples of these territories are Bantu peoples although they belong to branches of the Bantu language family, suggesting a complex history of populations, repopulations and movements between peoples. The main ethnic group is that of the Fang who occupy the most interior region and whose language, the Fang language, is a dialectal variety of Beti and is currently the majority ethnic group in Equatorial Guinea. Other ethnic groups located basically on the coast are:

- the molengues (kele group)

- People who speak Sawabantu languages, whose origin seems to be the coast of Cameroon. Among these groups are:

- the ndowés who speak kombe or ngumbi.

- The batangas, whose tongue the noho.

- the bengas whose tongue the benga.

- the ngumba, the kwasio, the gyele and the mabi, all speak kwasio (Makaa-njem group) that seem to proceed from the southeast of Cameroon.

Colonization of the island of Corisco

During the Iron Age (50 BC - 1400 AD) the island of Corisco was heavily colonized. The most important evidence of human occupation comes from the Nanda area, near the eastern coast of the island, where dozens of prehistoric burials have been excavated. These finds mainly belong to two different periods: Iron Age (50 BC). C. - 450 AD) and the Middle Iron Age (1000-1150 AD). During the first period, the islanders deposited, for example, piles of human bones and iron objects (axes, bracelets, spears, spoons, iron coin) in shallow pits dug in the sand. Ritual burial tombs from the second period have been documented.

The island was apparently abandoned around the 14th century century. After more than three centuries of abandonment, during which European and African sailors sporadically visited the island, Corisco was once again permanently occupied by clans of the Benga people, who stretched there from the coastal area of the Muni River in the second half of the 18th century, attracted by the prospects of trade with European navigators.

Colonization of the island of Bioko

Regarding the human colonization of the main island of present-day Equatorial Guinea, Bioko, it occurred between the V and VI AD. C. approximately, by small expeditions from different points of the Gulf coast, and configuring over time a socio-cultural group differentiated from their Bantu origins, the Bubi clans. Within popular mythology, the name of Momiatú has survived as the legendary leader of the first establishments. The clan structure that will be configured over time will maintain regular but weak communications with the continent. The island was given the name Etulá by the ancient Bubí settlers.

Portuguese rule (1471 - 1777)

Portuguese navigators were the first Europeans to truly explore the Gulf of Guinea in 1471. That year, the Portuguese Fernão do Pó (who was looking for a route to India) placed the island of Bioko on European maps. He christened her & # 34;Formosa & # 34; (beautiful). However, it was soon known by the name of its discoverer.

Around 1493, Don Juan II of Portugal added Lord of Guinea and first Lord of Corisco to the series of his royal titles. The Portuguese began colonizing the islands of Bioko, Annobón and Corisco in 1494, which became "factorías" or posts for the slave trade.

At the beginning of the XVI century (1507), the Portuguese Ramos de Esquivel made a first colonization attempt on the island from Bioko. He established a factory in Riaba and developed sugarcane plantations, but hostility from the Bubi island people and disease quickly put an end to this experience. The island's rainy weather, extreme humidity, and temperature swings killed most of the European settlers within weeks, and it would be centuries before the next attempt to establish a colony.

With the arrival of the Portuguese explorer Fernando Po, the life of the Bubi natives changed drastically. Some sources claim that up to 80% of the boobies died from diseases brought by the Europeans. Other sources suggest that the high death rate is the result of genocide. For several centuries the Europeans tried to penetrate the island of Bioko. However, they were met with great resistance and alleged savagery on the part of the Bubis. A merchant from the Brandenburg colony of Costa de Oro wrote "The island of Fernando Pó is inhabited by a savage and cruel people", and that the Europeans did not dare to land on it. its beaches for fear of surprise attacks by natives armed with bows; attacks on explorers and settlers were a common phenomenon at this time. In fact, the bubis had a social hierarchy that depended largely on how many rivals a man had killed stealthily or through subterfuge. Because of this, the Bubi were not conquered by European imperialism until the early 20th century. Led by their kings, the Bubi were aware of the slave trade in the region and, for centuries, kept out of reach of outsiders. This deliberate isolation would be reduced when the island's leaders began to trade with the Europeans, so that they were able to infiltrate the socio-political structures of the island.

Colonization of the island of Annobón (1592)

The Portuguese oceanic expedition led by João de Santarém and Pêro Escobar rediscovered the island of Annobón on January 1, 1475, seeking safe ports of call for the slave trade and the road to the Indies bordering southern Africa. Ano Bom, which they called "Ilha do Annobom" (or "Island of the Good Year"), had already been discovered in the reign of John II, hypothetically in 1484 by Diogo Cão. On December 21, 1474, João de Santarém discovered the island of Santo Tomé and Pêro Escobar discovered the island of Príncipe on January 17, 1475.

In 1525 the Spanish expedition led by García Jofré de Loaísa made a stop on the island of Annobón, which they named "San Mateo". In 1592 the Portuguese sent a junior governor of the governor of the island of São Tomé to Annobón, along with a schoolteacher and some Africans whom they called semi-civilized. In 1656, Diego Delgado, a resident of Santo Tomé of Spanish origin, tried unsuccessfully to establish sugar cane plantations on the island of Annobón.

Today, Annobonese Creole (fa d'Ambu), which is a Portuguese-based creole, is still spoken by some 5,000 people on the island of Annobón.

Dutch presence (1641-1648) and return of the Portuguese (1648-1777)

In 1641 the Dutch East India Company established itself without Portuguese consent on the island of Bioko, temporarily centralizing the Gulf of Guinea slave trade from there. Between 1642 and 1648, while Portugal was fighting Spain to maintain its independence, the Dutch took possession of the islands in the Gulf of Guinea. The Portuguese returned to make an appearance on the island in 1648, replacing the Dutch Company with one of their own, the Corisco Company, dedicated to the same type of trade. To this end, they built one of the first European buildings on the island, the Punta Joko fort.

Portugal sold slave labor from Corisco with special contracts to France (to whom it contracted up to forty-nine thousand Guinean slaves), Spain and England between 1713 and 1753, the main collaborators in this trade being the Bengas, a dedicated people to razzias or human captures, and that they had good relations with the European colonial authorities (who, in turn, did not intervene in the internal politics of the country, which undoubtedly helped), and that they also owned its own slave economic system, generally being its private servants the pamues and the nvikos.

Throughout this same century XVII an embryonic kingdom made up of the Bubi clans slowly took shape, especially after the action in this sense of some local chiefs such as Molambo (approx. 1700-approx. 1760) during a period of severe slavery in the area at the hands of the Portuguese, a situation that forced the Bubi clans to abandon their coastal establishments and settle in the interior of the island.

Spanish rule (1778-1968)

Beginning of the Spanish presence (1778-1827)

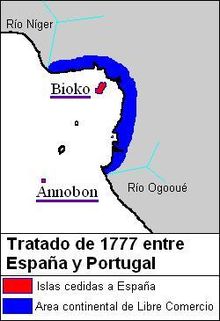

The continental territory and the islands that currently make up Equatorial Guinea remained in Portuguese hands until March 1777, after the treaty of San Ildefonso (1777) and El Pardo (1778) between Queen María I of Portugal and King Carlos III of Spain, by which the islands of Ano Bon and Fernando Pó (renamed Annobón and Fernando Poo respectively by the Spanish) were ceded to Spain, together with slave trade and free trade rights in a sector of the coast of the Gulf of Guinea, between the Niger and Ogooué rivers, together with the disputed Colonia del Sacramento, in Uruguay, in exchange for the area of the island of Santa Catarina, next to the Laguna de los Patos area, and the recognition of the Amazon as Portuguese territory, which became part of the Portuguese colony of Brazil. With this Spain intended to gain access to the source of slaves from which the British had been supplying the Spanish dominions in America.

From that moment on, the Spanish territory of Guinea was part of the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata (founded in 1776), until its final dismemberment with the May Revolution (1810) since the last concern of the First Governing Board in Buenos Aires was to assume political responsibility for the territory of Equatorial Guinea, given the host of problems it was facing and the lack of a concrete relationship between Buenos Aires and that region.

On April 17, 1778, an expedition made up of the frigates Santa Catalina and Soledad and the brig Santiago left Montevideo to take possession of of Fernando Poo and the rest of the territories on behalf of Spain, led by the Spanish brigadier Felipe de Santos Toro, VII Count of Argelejo, with the charge of receiving and taking possession of Equatorial Guinea from Portuguese hands on behalf of the Spanish crown and establish their government, subject to the authority of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. In the bay of Boloko (Bioko), the Count of Argelejo disembarked on October 24, 1778, taking possession of the place in the name of Carlos III, thus building the small town of San Carlos (current San Carlos de Luba). From that moment on, the island was administratively part of the Governorate of Fernando Poo y Annobón, integrated, together with the rest of the Spanish territories of Guinea, in the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata; from October 1778 to November 1780 a Spanish governor will be established.

The Count of Argelejo died on November 14, 1778 in Annobón, leaving Joaquín Primo de Rivera in command until an uprising of his troops on October 31, 1780 (of which 80% of the men had died from diseases) took him prisoner, leaving the mutineers the establishment of Concepción, first and provisional administrative center and moving to the island of Santo Tomé, belonging to Portugal.

From this event the two islands remained abandoned by Spain, which had doubts about their usefulness and decided not to invest in them, being instead visited and occupied by the British. However, although Spain decided not to colonize Fernando Poo and Annobón for now, it did continue to use them as a center from which to direct the slave trade on the nearby continental coasts with the support of British merchants.

In Bioko and during this period, the figure of a local chief stands out diffusely, Lorite (circa 1760 - 1810), who will be succeeded by Lopoa (circa 1810 - 1842). The latter's period of hegemony over the different clans on the island would include (or partially coincide in time with) the British intervention. At the beginning of the 19th century Bioko was a vital point for the transfer of slaves from Africa to the Americas. However, the flow of humans on the island was constantly intervened by indigenous groups that organized to steal and free as many slaves as possible. The island would be closed to human trafficking by the British government during the first half of that same century, occupying it militarily for a decade and a half.

British presence (1827-1843)

Unwilling to invest in the development of Fernando Poo, from 1827 to 1840 the Spanish allowed the United Kingdom to establish a base in the Malabo area due to the latter's interest in establishing a base in the region to control the Atlantic trade of slaves. Spain's decision to abolish slavery in 1837 at the insistence of Great Britain greatly diminished the perceived value of the colony to the authorities, making giving up naval bases an effective way to earn revenue in an otherwise worthless colony. Already in 1801 Spain had granted the right to the United Kingdom to use the island of Annobón as a port for freshwater supplies, building a small fort on it.

The British therefore occupied the island of Bioko between 1827 and 1840 under the formal pretext of "fighting the slave trade" (even though the British position in decades earlier had been prone to such trafficking). Thus, in 1827 and without Spanish permission, the headquarters of the Mixed Commission for the Suppression of Traffic was moved from Sierra Leone to Fernando Poo for the capture of slave ships and the persecution of traffickers, until it was transferred again to Freetown after a agreement with Spain in 1843.

In 1827 the settlement of Port Clarence (later Santa Isabel and today Malabo) was founded, named after the Duke of Clarence. A post was also established in the San Carlos de Luba area. Both were placed under the supervision of William Fitzwilliam Owen. During his three-year tenure, his forces claimed to have stopped twenty ships and freed 2,500 kidnappers to work as slaves, many of them settling in Port Clarence.

In 1841 the United Kingdom, interested in dominating Fernando Poo and Annobón, proposed to the Spanish government the purchase of the islands for sixty thousand pounds sterling. The sale of the colony was frustrated by the opposition of public opinion and the refusal of the Chamber of Commerce to allow the initiative to go ahead.

Restoration of the Spanish presence (1843-1900)

To strengthen the rights of Spain, the expedition of Juan José Lerena y Barry was sent, which in March 1843 raised the Spanish flag in Port Clarence (Malabo), renaming it Santa Isabel and receiving the formal submission of several local chiefs, establishing the administrative life of the colony, which he named "Spanish Territories of the Gulf of Guinea", and leaving the British John Beecroft as governor (who, in 1851, would leave Santa Isabel for the reduction of Lagos, thus marking the first British incursion into Nigeria having previously been appointed British consul in Benin and Biafra). Also, the Benga kingdom of the island of Corisco and the area of Cabo San Juan established a protectorate agreement with Spain in 1843 as a result of an arrangement between Juan José Lerena y Barry with the Benga king Bonkoro I, who died in 1846. Previously, in 1836 the Spanish navigator José de Moros had already visited the island of Annobón, ruled by King Pedro Pomba, reaffirming Spanish sovereignty over the island. Finally, in 1844 the United Kingdom abandoned its claims to the island of Fernando Poo in favor of Spanish sovereignty.

Due to the terrible epidemics that devastated the area, Spain still did not commit to developing the colony through financial subsidies for the arrival of settlers, which is why it would take another decade to carry out this direct control. The capital, Santa Isabel, already had more dynamism and the Protestant religious missions were having great success. Both elements helped to change Spain's attitude, in addition to the internal reasons already mentioned. For this reason, on September 13, 1845, the Royal Order was made public by which Queen Isabella II authorized the transfer to the region of all free blacks and mulattoes from Cuba who voluntarily so wished, believing that black people had a greater resistance to tropical diseases. On June 20, 1861, the Royal Order was published, converting the island of Fernando Poo into a Spanish prison; In October of the same year, the Royal Order was issued by which, since emancipated blacks from Cuba did not offer themselves voluntarily to immigrate to Guinea, it was provided that, if they did not present themselves, two hundred and sixty blacks would be shipped without their consent. Cubans, who will later be joined by political reprisals. The following year, in 1862, an outbreak of yellow fever killed many of the white settlers who had settled on the island. Even so, throughout the last third of the 19th century the number of plantations established by private citizens would continue to grow.

During the British period, they brought some two thousand freed and Sierra Leonean slaves to Bioko, who would end up establishing their own plantations and forming a black Creole elite that would dominate the insular society together with the Europeans: the Fernandinos. Limited immigration from West Africa and the West Indies had continued after the departure of the British. For this reason, during the entire XIX century most of Fernando Poo's plantations were mostly in the hands of this Creole elite. A number of freed Angolan slaves, Luso-African Creoles, and immigrants from Nigeria and Liberia also began to settle in the colony, where they quickly became part of Fernandina society. Several hundred Afro-Afro were also added to the ethnic mix. Cubans, 218 Filipino rebels (of whom only 94 would survive), and several dozen Spanish intellectuals and politicians deported to Fernando Poo for political reasons and other crimes, plus a small number of volunteer settlers. There was also a constant immigration of escaped slaves and fortune seekers from the neighboring Portuguese islands of São Tomé and Príncipe.

In 1870 the living conditions of the whites on the island improved thanks to the recommendation that they move to the highlands, and by 1884 much of the sparse colonial administration and large plantations had been transplanted to the Basilé Peak, hundreds of meters above sea level. Henry Morton Stanley called Fernando Poo "a jewel that Spain does not polish" for refusing to apply more aggressive colonization policies. Despite the increased chances of survival for Europeans on the island, Mary Kingsley, who spent time on the island, described it as "an uncomfortable form of execution" for the Spanish sent there.

A freedman from the West Indies relocated to Sierra Leone named William Pratt was the first to establish a cocoa plantation at Fernando Poo, thus sowing the seeds of the colony's economic future. At the end of the 19th century Spanish, Portuguese, German and Fernandino landowners began to develop large cocoa plantations. With the population Bubi Indian decimated by disease and resisting forced labor, the economy became dependent on imported farm laborers.

During these years, Spanish power gradually established itself among the natives as well, often with bad consequences. Starting in 1855, there was a hectic period of internal struggles in the Benga society of Corisco and Cabo San Juan over the issue of local chiefdoms caused by Spanish influence, struggles that ended in 1858 with the arrival of the first Spanish governor, Carlos de Chacón and Michelena, who appointed Munga I lieutenant governor of Corisco, faced Bonkoro II. Between 1859 and 1875 there was a Spanish garrison on the island, which would later be transferred to the island of Elobey Chico. It would not be until 1906 that the Benga kingdoms of Corisco and Cabo San Juan would reunify during the reign of Santiago Uganda after multiple civil wars between supporters of the Spanish and their detractors. Within this same policy of interventionism, in 1864 Governor Ayllón named the local chief Bodumba king of Elobey Grande.

Meanwhile, in Bioko the Bubi natives, who had historically managed to keep foreigners out and safeguard themselves from slavery and exploitation at European hands, came under increasing pressure from the Spanish administration and plantation owners. Madabita (approx. 1842-1860) and Sepoko (1860-1874/1875) will be the main local leaders in this period of growing Spanish intervention. Finally, in the second half of the s. In the XIX century, the unification of all the Bubi clans took place under King Moka (1875-1899) as a defense measure against colonialism, a situation that would not last long due to the growing Spanish colonial interventionism. During the period 1887-1897, several Spanish representatives established relations with King Moka of Bioko. They will be followed by Sas Ebuera (1899-1904) and Malabo (1904-1937), the latter king being imprisoned by the Spanish authorities in 1937, dying that same year and thus ending the monarchy, which since his accession to the throne in 1904 had had a merely symbolic role and subordinated to the Spanish authorities.

In turn, the continental region of the Gulf of Biafra will be widely explored by explorers such as Manuel de Iradier and Bulfy, who, in charge of two expeditions (in 1875 and 1884), will have the mission of putting down the uprisings of various villas-fang state and ensure their submission with the aim of establishing a Spanish presence in equatorial Africa, which will lay the foundations that will eventually give rise to the colony of Río Muni, although for the moment Spain will not ratify the protection agreements signed by Iradier with local bosses by establishing a stable presence in the region.

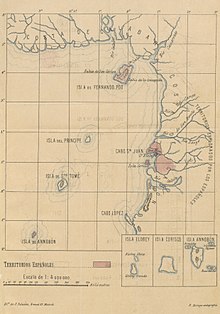

Territorial expansion by the Treaty of Paris (1900-1926)

Spain had not taken measures to occupy the large area of the Gulf of Biafra that corresponded to it according to the Treaties of El Pardo and San Ildefonso, and, instead, France had been colonizing the areas claimed by Spain. Madrid had not reinforced the explorations of men like Manuel Iradier, who had signed protection treaties with tribal chiefs for large territories in Cameroon and Gabon, leaving most of these lands without effective occupation under the terms stipulated in the Berlin Conference of 1885. Subsequent events in Cuba and the Philippines and the war against the United States in 1898 distracted the Spanish government from the colonial enterprise at a critical time. What little support there was for the annexation of territories in continental Africa was due exclusively to public opinion and the need for manpower for Fernando Poo's plantations. During the last third of the century XIX and since 1885 the towns on the Equatoguinean continental coast that signed treaties with Spain were under its protectorate, and in 1900 the area under Spanish control would be officially united as a colony. Similarly, in 1903 the colony of Elobey, Annobón and Corisco would also be created.

The eventual Treaty of Paris of 1900 defined and established the precise limits on the borders between the French and Spanish territories in Western Sahara and in the Gulf of Guinea, leaving Spain with a meager enclave centered around the Muni River in a mere 26,000 km² of the 300,000 he had initially claimed as far east as the Ubangui River. Spaniards had considered that it belonged to them based on their rights and the Treaty of El Pardo. The humiliation of the Franco-Spanish negotiations, combined with the Spanish-American War of 1898, led the head of the Spanish negotiating delegation and governor of Río Muni, Pedro Gover y Tovar, to commit suicide on the return trip to Spain on October 21, 1901. Iradier himself died in ignominy in 1911 and it would not be until decades later that his achievements would be taken into account by Spanish popular opinion when the city of Cogo was renamed Puerto Iradier in his honor.

According to the text of the 1900 Treaty, the territories exchanged with the delimitation established in the text would be transferred of administration on March 27, 1901, or earlier if possible. In this regard, the political-administrative structure of the colonial territories involved in the Treaty was theoretically sustained by the survival of traditional pre-Western structures rooted in the society of the time and based on clans:

Art. 9. - The two contracting Powers undertake to treat with benevolence the Chiefs who, having concluded Treaties with one of them, remain under this Convention under the sovereignty of the other.Convention between Spain and France

(Gaceta of 30 March 1901)

The early years of the 20th century saw a new generation of Spanish immigrants. The land regulations approved in 1904-1905 favored the Spanish, and most of the large plantations created since then were owned by Spanish settlers. All this put the Fernandinos on the defensive. At that time most of the plantations were still owned by them, and although a handful of Fernandinos were Catholic and Spanish-speaking, about nine out of ten were still Protestant and English-speaking at the start of World War I, and a pidgin of English was the language. of the island, which is why they often showed their opposition to the control that the Spanish colonial administration tried to establish over the island and made Spain's colonizing task even more difficult. The Sierra Leoneans had a particularly entrenched position as plantation owners, while the recruitment of braceros in present-day Côte d'Ivoire continued thanks to their good connections and continued contact with their relatives there, so they were not affected by the problem. of the constant labor shortage. The Fernandinos proved to be good traders and intermediaries between the natives and the Europeans.

On the island of Bioko and the rest of the territories, the exploitation of its wealth began and a true colonial government was established. The great problem of the colony was, as always, the chronic lack of manpower. Pressed inland and decimated by alcoholism, forced labor, venereal disease, smallpox, and sleeping sickness, the indigenous Bubi population had always done everything possible not to work on the plantations. Working on their small cacao farms gave them a considerably greater degree of autonomy and allowed them to earn a subsistence income without needing to be exploited. Furthermore, the bubis had been protected from the demands of landowners since the late s. XIX by the Spanish Claretian missionaries, who had great influence in the colony and who eventually organized the Bubis into small theocratic missions similar to the famous Jesuit reductions of the 17th-18th centuries in Paraguay and the Banda Oriental, in Spanish America, where the Jesuits acted in a similar way with the indigenous Guarani.

Catholic penetration was reinforced by the armed resistance of the Bubi to the conscription of forced labor for the plantations. Among these, the 1898 rebellion led by Sas-Ebuera stands out, who formed nationalist and anti-colonialist militias. He was captured by the Spanish forces and his refusal to accept the authority of the colonial governor led him to maintain a hunger strike, dying on July 3, 1904. Also Malabo Lopelo Melaka (king between 1904 and 1937), Moka's son, will initiate a moderate demand for their rights, with the last confrontation of the Bubis against the Spanish colonizers in 1910 in the San Carlos region, which began after the murder of the Spanish corporal León Rabadán and two indigenous policemen. In that event, about 1,500 bubis died,[citation needed] between civilians and rebels. Immediately after the 1910 insurrection, colonial forces pressured King Malabo to influence local chiefs to prevent further confrontation. Finally, in 1917 the Spanish disarmed the Bubis, leaving them totally dependent on the missionaries.

Due to the lack of manpower, a contract was signed with the Republic of Liberia in 1914, by which about fifteen thousand Liberian workers were transported to the Spanish colonies over sixteen years, transport that ran to by the German shipping company Woermann-Linie. This greatly favored the large landowners, as it gave them easy access and at low prices to the always scarce workforce, and the increasing exploration and colonization of Río Muni through the model of plantations and its territory much larger than that of Fernando Poo but with a small population made the agreement with Liberia even more beneficial for the settlers. In 1940 it was estimated that only 20% of local cocoa production came from land owned by Africans, and, in turn, of this 20%, almost all the land was in the hands of the Fernandinos, who had been displaced from their land. niche of power after the arrival of large numbers of Spaniards. However, the agreement was canceled in 1930 after an International Labor Organization commission discovered the slave-like conditions in which Liberian imported workers were held, revelations that brought down the government of Liberian President Charles D.B. King.

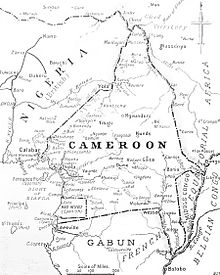

From the Franco-German agreements of 1911 to solve the second crisis in Morocco, Río Muni had been completely surrounded by the German colony of Kameroon and not far from French Equatorial Africa. In those years the Spanish presence was almost purely token, limited almost entirely to the coast and concentrated in the capital, Bata (founded in 1900 by the French as a trading post before the territory passed into Spanish hands by the Treaty of Paris and which in 1914 had a population of only a few dozen white settlers), the troops of the colonial guard barely numbered two hundred men, and the mainland was inhabited by the Fang tribes who were still in the process of being converted. submit.

World War I

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914 (in which Spain declared itself neutral), when fighting began between colonial troops, there was fear on the part of the Spanish authorities that this fighting would move to Río Muni. To solve the problem, Governor Ángel Barrera had four very simple military posts (Mibonde, Mikomeseng, Mongomo and Ebibeyín) installed (without radio stations or machine guns and with very few soldiers), but which were enough to show the symbolic limits of the Spanish sovereignty and fulfilled their function, avoiding the extension of the war towards Continental Guinea. These bases later became centers of commercial growth and from there attacks were launched against the fang who resisted colonization. Although there were fears for the integrity of the colony given the possibility that the fighting would cross the borders between the German and Spanish colonies, this did not come to pass. At that time Río Muni was beginning to be explored and Spanish control was slowly asserting itself in the inland territories.

With the German defeat in Cameroon in February 1916, a contingent of about a thousand Germans, including soldiers and civilians, and forty-six thousand indigenous people, including askari soldiers, porters, and the civilian population, took refuge in Bata, making the Spanish colonial authorities serious. lodging and food problems, as well as enormous difficulties in organizing their repatriation. The two hundred Spanish soldiers found themselves overwhelmed, although the Germans surrendered and surrendered their weapons peacefully, so Governor Barrera decided to return twenty-five thousand of the Cameroonians to the other side of the border, leaving some twenty-seven thousand refugees in his territory. Of the more than 25,000 people left in Guinea, between 800 and 1,000 were Germans (only half of them soldiers), 6,000 were askaris, and the rest were service personnel (such as porters, butlers, or interpreters) and civilians (mainly women). families of soldiers). Under pressure from France and the United Kingdom, who feared that the soldiers would rejoin the fight, half of the refugees (including all the Europeans) were transferred to Fernando Poo, placing them in camps near Santa Isabel. About a thousand people died from the poor conditions in the refugee camps. During their stay in Fernando Poo, the Cameroonian natives served to temporarily alleviate the shortage of labor in the cocoa plantations.

In the end, on December 30, 1916, Spain sent an expeditionary company of Marine Infantry to take care of the German and Cameroonian refugees. The bulk of Cameroonians returned to their country in 1917, although some remained to live on the island, while German civilians were transferred to the Iberian Peninsula and German officers remained in the Spanish colony until the end of the war. During this period there were some confrontations with the local Fang population from the mainland, such as those that gave rise to the punitive expedition of Río Muni in 1918, or those caused by forced labor imposed by Lieutenant Julián Ayala Larrazábal.

Spanish Guinea (1926-1968)

Colony of Spanish Guinea (1926-1956)

Both the insular and mainland territories were united in 1926 as the colony of Spanish Guinea. Around this time, the previous traditional structures of the tribal kingdoms ended, consolidating the European-style administration imported by the Spanish, under the nominal reign of King Malabo in Bioko, between 1904-1937, the latter year in which the king was imprisoned by the Spanish authorities.

However, Spain lacked the necessary wealth and interest to develop a significant economic infrastructure during the first half of the 20th century. Nonetheless, Spain developed large cocoa plantations on the island of Bioko with thousands of peons imported from neighboring Nigeria.

In the 1930s, Equatorial Guinea remained faithful to the Second Spanish Republic until September 1936 when, after the Spanish Civil War had already started, it joined the Uprising against the Republic. In 1942, during the Second World War (in which Spain declared itself non-belligerent), the so-called Operation Postmaster took place in Equatoguinean territory.

Gulf of Guinea Province (1956-1959)

Until 1956, the islands of Bioko, Annobón and Corisco together with the mainland (Río Muni), formed part of the Territory of Spanish Guinea. On August 21, 1956, these territories were organized into a province with the name of Province of the Gulf of Guinea.

During this period, the first independence movements began to emerge timidly in the country, such as the one led by Acacio Mañé Ela.

Provincial Councils of the Equatorial Region (1959-1968)

In 1959 the Spanish territories of the Gulf of Guinea acquired the status of overseas Spanish provinces, similar to that of the metropolitan provinces. By the law of July 30, 1959, they officially adopted the name of the Spanish Equatorial Region and was organized into two provinces: Fernando Poo and Río Muni.

As such, the region was governed by a Governor-General exercising all civil and military powers. The first local elections were held in 1960, and the first attorneys in Equatoguinean courts were elected. In September 1960, the Provincial Council of Fernando Poo (chaired by Alzina de Bochi) and the Provincial Council of Río Muni (chaired by José Vedú) were constituted. Fernando Poo) and Federico Ngomo (Río Muni).

Autonomous Region of Equatorial Guinea (1963-1968)

On December 15, 1963, the Spanish government submitted to a referendum between the population of these two provinces a draft Bases on Autonomy, which was approved by an overwhelming majority. Consequently, these territories were endowed with autonomy, officially adopting the name of Equatorial Guinea, with bodies common to the entire territory (General Assembly, Government Council and General Commissioner) and bodies belonging to each province. Although the general commissioner appointed by the Spanish government had broad powers, the General Assembly of Equatorial Guinea had considerable initiative in formulating laws and regulations. Its first and only president was Bonifacio Ondó Edú. For its part, the Equatoguinean General Assembly was chaired by Enrique Gori from 1964 to June 1965, when he handed over the post to Federico Ngomo.

In November 1965, the IV Committee of the UN Assembly approved a draft resolution asking Spain to set the date for the independence of Equatorial Guinea as soon as possible. In December 1966 the Council of Ministers of the Spanish Government agreed to prepare the Constitutional Conference. Said Conference was inaugurated in October 1967, chaired by Fernando María Castiella, Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs; At the head of the Guinean delegation was Federico Ngomo.

Independent state (1968-present)

Proclamation of Independence (1968)

In March 1968, under pressure from Equatorial Guinean nationalists and the United Nations, Spain announced that it would grant independence. A Constitutional Convention was formed which produced an electoral law and a draft constitution. After the second phase of the Constitutional Conference (April 17 - June 22, 1968) the consultation was held. The referendum on the constitution took place on August 11, 1968, under the supervision of a United Nations observer team. Some 63% of the electorate voted in favor of the new constitution, which provided for a government with a General Assembly and a Supreme Court with judges appointed by the president.

On September 22, the first presidential elections were held and none of the four candidates obtained an absolute majority. A week later, Francisco Macías Nguema was elected president of Equatorial Guinea; His immediate follower in the election was Bonifacio Ondó Edú.

In September 1968, Francisco Macías Nguema was elected the first president of Equatorial Guinea with the support of nationalist movements such as IPGE (Popular Idea of Equatorial Guinea), part of MONALIGE (National Movement for the Liberation of Equatorial Guinea) and the Bubi Union. The independence of Equatorial Guinea was proclaimed on October 12, 1968. The country adopted the name of the Republic of Equatorial Guinea. She was admitted to the UN as the 126th member of the Organization.

Crisis of 1969

In January 1969, the leader of the opposition to Macías, Bonifacio Ondó Edú, who was under house arrest, was assassinated. Instability in the country increased.

In March 1969, Macías announced that he had mastered a coup attempt headed by the opposition Atanasio Ndongo (versions vary: although some authors claim that it had never existed, others affirm that the attempt actually took place). The Equatoguinean president took advantage of this pretext to put an end to all the opposition and establish a sinister dictatorship. Atanasio Ndongo's followers were arrested or killed. The failed coup or false coup generated a wave of anti-Spanish popular indignation (stimulated by the government), for which the Spanish community felt threatened. All this situation resulted in a diplomatic crisis between Spain and Equatorial Guinea.

On March 28, 1969, the Spanish troops stationed in Río Muni re-embarked. The same will happen on April 5, leaving the island of Fernando Poo. The Spanish presence in Equatorial Guinea had ended.

The Macías dictatorship (1968-1979)

Macías did not take long to concentrate in his person all the powers of the State and in July 1970 he created a single party regime, the PUNT (Partido Único Nacional de los Trabajadores); the People's Republic of China sent 400 experts (doctors, engineers and builders) to the country, along with financial assistance. The Soviet Union sent weapons material and military advisers, receiving in return fishing rights and rights to use the port of San Carlos de Luba. In May 1971 crucial parts of the Constitution were repealed. An educational cooperation agreement was signed with Cuba at the end of 1971, and North Korea began to send military instructors for the militias created by Macías and for the National Guard. The uniform of the PUNT Militias and Youth became similar to that of the Maoist Red Guards and the president ordered the burning of all books published in the West, as well as libraries dating from the colonial era in an imitation of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966 - 1976); and in July 1972 he proclaimed himself president for life.

At the beginning of 1973, all Catholic and Protestant priests, foreigners or not, were placed under house arrest, also beginning a persecution of believers in those religions, under the form of subversion, punishable by a fine of 1000 Guinean pesetas and the obligation to make a declaration affirming that “God does not exist”.

1973 Constitution

In July 1973, he promulgated a new Constitution (the second in the country), tailor-made for him, which created a unitary State, annulling the previous status of federation between Fernando Poo and Río Muni. He carried out a relentless crackdown on his political opponents. These were liquidated in prisons by means of simple and brutal beatings. Because of his dictatorial methods, more than 100,000 people fled to neighboring countries; at least 50,000 of those who remained in the country died, and another 40,000 were sentenced to forced labor.

On June 13, 1974, Radio Malabo and Radio Ecuatorial Bata announced the news of a plot prepared from Bata with material and financial help from abroad and of acts by the subversive prisoners after breaking the prison walls. At the same time, the official government spokesman appealed to the population to report any suspect. The authorities made Estanislao Ngune Beohli and a group called the Equatorial Guinea Liberation Crusade for Christ the main responsible for the alleged plot, pointing out Pelagio Mba, Antonio Edjo, Lucas Ondo Micha, Manuel Ncogo Eyui, Expedito Rafael Momo Bocara as their collaborators., Manuel Combe Madje, Lorenzo May, Ricardo Mba Mangue, Terencio Borico, Patricio Meco Nguema and Felipe Aseko, all of them tried by a Popular Military Court chaired by Fortunato Okenve Mituy and sentenced to death (except three of them, with sentences of between 17 and 29 years in prison).

The Macías regime was characterized by the abandonment of all government functions with the exception of internal security. Due to theft, ignorance and negligence, the country's infrastructure - electricity, water supply, roads, transport and health - fell into ruin. Schools were closed in 1975. Nigerian indentured laborers, who carried out the bulk of the work on the Bioko cocoa plantations, were deported en masse in early 1976. foreigners left the country. At the end of 1976 there was also another coup attempt.

Catholic worship finally banned in June 1978. Nguema implemented a toponymic Africanization campaign, superficially imitating the socio-cultural movement of negritude, replacing colonial names with native names: the capital Santa Isabel became Malabo, the island of Fernando Poo was renamed "Isla de Masie Nguema Biyogo" in memory of the dictator himself, and Annobón became Pagalú. As part of the same process, the entire population was ordered to change their European names to African names. The dictator's own name underwent several transformations, so that at the end of his government, he was known as Masie Nguema Biyogo Ñegue Ndong.

The regime of Teodoro Obiang (1979-present)

The "Freedom Strike" and the Supreme Military Council (1979-1982)

On August 3, 1979, Macías was overthrown by a coup led by a group of officers from the Zaragoza Military Academy, including Eulogio Oyó Riqueza, and led by Macías' nephew, Lieutenant General Teodoro Obiang, who had been warden of the Black Beach prison. This group became a Revolutionary Military Council chaired by Obiang himself.

The islands were renamed Bioko (formerly "Isla de Macías Nguema Biyogo") and Annobón (formerly "Isla de Pagalú"). The new regime had an enormous task before it: the state coffers were empty and the population was barely a third of what it was at the time of independence.

On August 25, the PUNT was dissolved and the Revolutionary Military Council was renamed the Supreme Military Council. Macías was tried, sentenced to death, and executed on September 29, 1979. The Constitution of Equatorial Guinea of 1973 was also abolished.

On October 12, 1979, Teodoro Obiang proclaimed himself president of the country. Spain and the African country signed a Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation in October 1980.

1982 Constitution

In July 1982, the Supreme Military Council appointed Obiang President of the Republic for a period of seven years, while a new constitution (the third in the country) was promulgated, approved in a referendum (August 15, 1982). The Supreme Military Council was dissolved on October 12, 1982.

On December 19, 1983, Equatorial Guinea joined the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) and the Central African Customs and Economic Union (UEDAC), and shortly after the Economic Community of the Central African States, so in January 1985 it adopted the CFA franc as its currency.

Elections of 1983 and 1988

In 1983 and 1988 parliamentary elections were held, attended by a single list of candidates. In 1987, Obiang had announced the formation of the Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea (PDGE) with a view to the presidential elections to be held in 1989. Obiang was re-elected as the only candidate. However, he did not manage to get the country out of the deep economic crisis in which he found himself plunged.

In July 1988, single-list legislative elections were called for the House of People's Representatives. On June 25, 1989, presidential elections were held.

1991 Constitution

In 1991 a timid democratization began, essential for the continued economic aid from Spain, France and other countries. In November, a new constitution (the country's fourth) was approved in a referendum that established a system of parliamentary representation for legalized political parties. Given the announcement of this timid opening, many political opponents returned to the country, only to be imprisoned by Obiang (January-February 1992).

1993 Elections

Months later, various opposition political formations were legalized. However, in the 1993 legislative elections, ten of the fourteen registered parties were banned, which resulted in around 80% abstaining from voting. The official results gave the PDGE the winner, with which Obiang continued in power as head of state and government. After these elections, not only was the regime not democratized, but in 1995 the opposition leader Severo Moto Nsá was imprisoned on charges of corruption and slander. Likewise, a repression was carried out against the political opposition population on September 17, 1995 in the town of Miboman in Ebebiyín.

1996 Elections

The year 1996 was a crucial year for the future evolution of the country. That year, the American multinational Mobil began extracting oil in Equatoguinean territory, which would result in a considerable increase in income for the country (monopolized by Obiang and the ruling clique).

The presidential elections of 1996 were strongly questioned internationally. The candidate of the Joint Opposition Platform (POC), Amancio Nsé, was not allowed to participate in them, using an electoral law tailored to the president. Consequently Obiang was re-elected with 98% of the vote. To counter the criticism, Obiang appointed a new government in which opposition figures held some minor positions. In 1998 a trial was carried out without any procedural guarantee against 117 members of the Bubi ethnic group (the Nguema family belongs to the fang, the majority in the country) close to the opposition group MAIB (Movement for Self-Determination of the Island of Bioko), allegedly involved in an assassination attempt. The mock trial ended with fifteen death sentences. That same year, a constitutional law was approved, modifying article 4 of the Fundamental Law of the State, and establishing that the official languages of the Republic of Equatorial Guinea are Spanish and French, and recognizing the autochthonous languages as members of the national culture. (Constitutional Law No. 1/1998 of January 21).

The legislative elections of March 1999 saw a new landslide victory for the president's party, the PDGE (which went from 68 to 75 seats in a chamber of 80). The main opposition parties, the Convergence for Social Democracy (CPDS) and the Popular Union (UP), which won four and one seats respectively, refused to take possession of them.

The local elections of May 2000 marked another overwhelming victory for the PDGE, which thus controlled all the important municipalities in the country. The main opposition parties described the elections as rigged and boycotted them.

Elections 2002

On December 15, 2002, all four of Equatorial Guinea's main opposition parties withdrew from the country's presidential election. Despite allegations of fraud by the opposition, Obiang won the elections and was re-elected, revalidating his mandate for another seven years (until 2009). These elections were widely considered fraudulent by members of the Western press.

In 2003, an Equatorial Guinean Government in Exile was formed, led by Severo Moto. Apparently, they hired a company based in the Channel Islands to overthrow the Obiang government. In March 2004, 64 suspected mercenaries were detained at Harare airport (Zimbabwe) after they withheld information about their cargo and crew. In 2004, the son of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Mark Thatcher, was arrested in South Africa on charges of aiding a failed coup attempt.

That same year, 2003, President George Walker Bush resumed diplomatic relations with the Equatorial Guinean government, which had been interrupted in 1995 when President Bill Clinton's ambassador, wanting to promote the cause of human rights, was threatened with death and ordered to leave the country. A year later there was an attempted coup in Equatorial Guinea in 2004.

Equatorial Guinea was accepted as an associate observer in July 2006 in the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), and in July 2007, Teodoro Obiang announced his government's decision to make Portuguese the co-official language of Equatorial Guinea, to satisfy the requirements to request full membership of the CPLP.

In March 2008, several members of the opposition Progress Party were arrested, including the former secretary of Severo Moto (the party's president), Gerardo Angüe Mangue. One of them, Saturnino Nkogo, died during his detention under strange circumstances. Six other PP activists, Cruz Obiang Ebele, Emiliano Esono Michá, Juan Ecomo Ndong, Gumersindo Ramírez Faustino and Bonifacio Nguema Ndong were tried together with Simon Mann, a citizen who had helped organize a coup attempt in 2004. Members of the group were sentenced to between one and five years in prison each. Their imprisonment was protested by the US State Department and Amnesty International. A few months later, legislative elections were held.

In September 2008, the Equatorial Guinean ambassador to Cameroon, Florencio Mayé Elá, was involved in the kidnapping of political opponent Cipriano Nguema Mba, after which the ambassador was declared persona non grata.

2009 Elections

In December 2007 and February 2009, the Nigerian group Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta was blamed for carrying out armed incursions into the country for the purpose of looting, including an attempt to assault on the presidential palace. For the attempted assault on February 17, 2009, José Abeso Nsue, Manuel Ndong Anseme, Jacinto Micha Obiang and Alipio Ndong Asumu were arrested, accused of attempted coup d'état.

In October of the same year there was a diplomatic incident with Cameroon, the Government of Yaoundé prohibited Equatorial Guinean airlines from traveling to its territory, two weeks after Malabo suspended the flights of a Cameroonian company to Equatorial Guinea, and in parallel to the meetings held for the delimitation of the maritime border between the two countries.

In November 2009, presidential elections were held, with Teodoro Obiang remaining in power. In July 2010, he requested to be a full member of the CPLP, without success, and in 2011 the Obiang government introduced reforms to make Portuguese official. In 2011 the government announced the creation of a new capital for the country, Djibloho. On July 20, 2012, the CPLP again rejected Equatorial Guinea's request to be considered a full member.

2010s

In 2011, a constitutional referendum was held, in which reforms such as the reinstatement of the position of Vice President, the creation of the Senate, and the limitation of the presidential mandate to two periods were approved.

In the 2013 legislative elections, the PDGE won 69 of 70 seats in the Senate and 99 of 100 parliamentarians in the Chamber of Deputies. The CPDS denounced the elections as fraudulent.

On April 24, 2016, new presidential elections took place, in which Obiang obtained 93.5%.

In 2017, the prominent cartoonist and opponent of Obiang Ramón Esono Ebalé was arrested and imprisoned in the Playa Negra Prison. That same year, Vice President Teodorín Nguema Obiang was sentenced in Paris to a suspended sentence of three years in prison for corruption.

The 2017 legislative elections resulted in a new victory for the PDGE, which obtained all the senators and 99 of the 100 deputies, with the remaining seat corresponding to the Ciudadanos por la Innovación (CI) party. This party was shortly after accused of organizing a coup and 146 of its militants were put on trial in February 2018. The verdict of the trial was announced on February 26. 36 defendants (including party deputy Jesús Mitogo Oyono) were sentenced to 26 years in prison (it was initially erroneously reported that the sentences were 44 years). the sentence included the banning of CI. CI announced its intention to appeal the sentence, which it finally materialized by filing a cassation appeal before the Supreme Court of Justice. In an official statement from Spain, the Party Popular, the Spanish Socialist Workers Party, Unidos Podemos, En Comú Podem, Ciudadanos, and the Basque Nationalist Party denounced the persecution of the opposition party and demanded "respect for human rights, public liberties, and the elementary norms of the democracy". The Spanish government contacted Gabriel Nsé Obiang (CI leader) and assured that they would maintain a constant dialogue with the Guinean opposition to promote democracy. In March 2018, the Senate or Spaniard Carles Mulet García de Compromís drafted a question in the Spanish Senate, answered by the Spanish Government in May of the same year, alluding to the events related to CI that occurred in Equatorial Guinea. In contrast, the PDGE justified the sentences, which was disowned by CI.

Regarding the case of Ramón Esono, in the first session of the trial held on February 27, 2018, the prosecution withdrew all charges against Esono as it did not find sufficient evidence to incriminate him. The witness of In charge, National Police Corporal Trifonio Nguema Owono Abang, was unable to sustain his accusations in court and acknowledged that he was "following orders" when accusing Esono Ebale. The artist was released on March 7.

In April 2018, Equatorial Guinea organized the so-called "International Colloquium on Human Rights and Civil Society", in which ambassadors, international experts and heads of diplomatic missions participated. This event was criticized by opposition parties such as CI, given the political situation in the country. On May 2, 2018, the trial of the appeal filed by the party to revoke its illegalization began. Fabián Nsue and Ponciano Mbomio. The final sentence was handed down on May 7, and confirmed both the banning of CI and the convictions of its militants. CI disagreed with the verdict and accused the Guinean judicial system of being manipulated by the government. The banning of CI was also condemned by the Convergence for Social Democracy (CPDS). On May 17, CI Secretary General María Jesús Mene Bopabote traveled to Brussels and was received by the ins institutions of the European Union, presenting a file on the violations of human rights committed by the government.

On May 23, President Obiang met with a Spanish delegation led by the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Ildefonso Castro López, who conveyed the desire of the Spanish Government to accompany the authorities and the people of Equatorial Guinea in the 50 anniversary of its independence. Castro also met with opponents Andrés Esono Ondó (leader of the Convergence for Social Democracy) and Avelino Mocache (leader of the Center Right Union), with whom he discussed the political situation in Equatorial Guinea.

In June 2018, the International Court of Justice agreed to determine whether the expropriations of several properties belonging to Vice President Nguema Obiang by the French authorities were correct, during his judicial process. On June 7, CI filed an an appeal for amparo before the Constitutional Court on the grounds that the sentence ratified against him violated the Fundamental Law of Equatorial Guinea.

On June 11, Obiang convened a National Dialogue Table (the sixth in the country's history) for the month of July and in which all legal and non-legalized political parties in the country could participate, as well as opposition formations in exile. This call was received with optimism by CI (although it criticized the government for not explaining the content of the project) and with skepticism by CPDS. The process was called by presidential decree on June 13. established the period between July 16 and 21 as the date for the event. CI and CPDS set the release of political prisoners, the participation of civil society and the presence of the international community as a condition for participating in the process The Obiang government agreed to this last point by inviting foreign personalities to the Dialogue, however it did not allow CI's participation, arguing that it had previously been outlawed. CI condemned in a statement the attitude of the government. For its part, the Progress Party of Equatorial Guinea described the National Dialogue as a "deception" of Obiang. The Union for Democracy and Social Development (UDDS) and the Republican Democratic Force (FDR) set a series of conditions to participate. The National Coordinator of Civil Society Organizations congratulated Obiang for the call, as did the United Nations, an organization that also announced that it would send an observer to the event. The CORED Coalition, a formation in exile, expressed its intention to participate by videoconference.

On July 4, the Obiang government announced a general amnesty for all political prisoners with a view to the Dialogue Table convened by the government weeks before. CI, the CPDS and the FDR welcomed the measure, but they denounced the arbitrariness of the regime. The Government of Spain and Amnesty International spoke similarly. The Guinean government criticized the Spanish government for an attitude that it described as "interference". Days after the amnesty decree was sanctioned, the opposition denounced that it had not yet been put into practice. CPDS also criticized the organization of the Dialogue Table, which in their opinion excluded opposition parties. The National Dialogue began on July 16 at the Sipopo Conference Center with the participation of 17 political parties (including CPDS) and the absence of CI, which regretted its exclusion. On the eve of the start of the event, the European Union asked participate as an observer. During the event, the opposition parties again denounced the breach of the amnesty and the imprisonment of several Supreme Court magistrates, one of whom died in prison. The CPDS even requested the resignation of the Government and the establishment of a transitional government, a proposal that was rejected by the Executive. The Dialogue Table was finally extended until July 23, waiting for the participants to close agreements. After the closing of the process, agreements were reached such as greater respect for human rights, projects on cultural affairs and construction of public schools. The Government positively assessed the Dialogue Table, and President Obiang declared that he was satisfied and encouraged by its result. However, opposition parties such as the CPDS and the Center Right Union (UCD) considered the process fruitless and refused to sign the final agreement document. held a meeting between the government and political parties in which the authorities unsuccessfully tried to convince CPDS and UCD to sign the document. CI also assessed the results of the Dialogue Table as a failure, as did the opposition in the exile.

In October 2018, on the eve of the 50th anniversary of Equatorial Guinea's independence, all CI prisoners were pardoned, including its elected deputy Jesús Mitogo. Its leader Gabriel Nsé declared that he hoped to regain the party's parliamentary seat. However, CI also denounced that the detainees were not immediately released. On October 22, they were finally released, an attitude that was congratulated by the Spanish government and the opposition both at home and in exile. However, the leadership of the formation noted that several released showed signs of torture. Likewise, the authorities prevented the party from recovering its parliamentary seat.

On October 12, 2018, Equatorial Guinea celebrated 50 years of independence. The government held a massive event that was even attended by several heads of state from the African continent. For its part, the opposition in exile held a rally protest in front of the Equatorial Guinean embassy in Spain and the government of this country congratulated Equatorial Guinea on its independence anniversary, although it urged the Obiang government to stop the political repression.

In May 2019, following a controversial trial, more than 130 people were sentenced to prison for their role in the 2017 coup attempt.

Thanks to oil revenues, whose production has increased tenfold in recent years, Equatorial Guinea has experienced growth rates of 33%. However, such an influx of wealth is not serving to improve the economic conditions of the population, but has served to grant certain "legitimacy" the regime with visits by representatives of the US and Spanish governments, among others, pressured by the US oil industry (present in Equatorial Guinea with Exxon Mobil, ChevronTexaco and Triyo Energy), the United States resumed diplomatic relations (2003), interrupted since 1995. Not surprisingly, Equatorial Guinea is the third largest producer of crude oil in sub-Saharan Africa (after Angola and Nigeria).

The government of Teodoro Obiang Nguema is considered one of the most repressive in the world, according to international human rights organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.[citation needed] Specifically, the disappearances of activists, torture, the lack of press freedom, the lack of real legal guarantees, the manipulation of electoral processes and the extremely unequal distribution of the country's wealth have been denounced.[citation required]

2020s

On March 7, 2021, there were ammunition explosions at a military base near the city of Bata that caused 98 deaths and 600 people were injured and treated in hospital.

In November 2022 Teodoro Obiang was re-elected in the 2022 Equatorial Guinea general elections with 99.7% of the vote amid accusations of fraud by the opposition.

Contenido relacionado

Gothic art

Methodism

Barceo