History of christianity

The history of Christianity refers to the Christian religion, its followers and the Christian Church, with its different denominations, since the I to the present. Christianity originated with the ministry of Jesus, a Jewish teacher and miracle worker who proclaimed the imminent arrival of the Kingdom of God and was crucified around AD 30-33. C. in Jerusalem, in the Roman province of Judea. His followers believe that, according to the Gospels, Jesus was the Son of God and that he died for the forgiveness of sins and was resurrected and exalted by God, and that he will soon return to heaven. beginning of the Kingdom of God.

The first followers of Jesus were apocalyptic Jewish Christians. The inclusion of "gentiles" (i.e., non-Jews) in the developing early Christian Church caused the separation of early Christianity from Judaism during the first two centuries of the Christian era. In 313, the Roman Emperor Constantine I promulgated the Edict of Milan legalizing Christian worship. In 380, with the Edict of Thessalonica promulgated under Theodosius I, the Roman Empire officially adopted Trinitarian Christianity as their state religion, and Christianity established itself as a predominantly Roman religion in the state church of the Roman Empire. Various Christological debates about the human and divine nature of Jesus consumed the Christian Church for three centuries, and seven ecumenical councils were convened to resolve these debates. Arianism was condemned at the Council of Nicea I (325), which supported the trinitarian doctrine expounded in the cre of Nicene-Constantinopolitan.

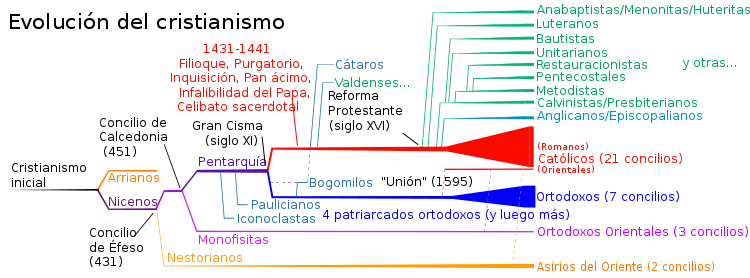

In the Early Middle Ages, missionary activities spread Christianity to the west and north (among the Germanic peoples); to the east (among the Armenians, Georgians, and Slavic peoples), in the Middle East (among the Syrians and the Egyptians), in East Africa (among the Ethiopians), and beyond, in Central Asia, China, and India. During the High Middle Ages, Eastern and Western Christianity drifted apart, leading to led to the East–West Schism of 1054. Increasing criticism of the Roman Catholic church structure and its corruption led to the Protestant Reformation and related reform movements in the XV and XVI, which ended with the European religious wars that unleashed the split from Western Christianity. Since the Renaissance era, with the European colonization of the Americas and other continents actively instigated by Christian churches, Christianity has spread throughout the world. Today, there are more than two billion Christians throughout the world, and Christianity has become the world's largest religion. Over the past century, as the influence of Christianity has progressively waned in the Western world, Christianity remains the predominant religion in Europe (including Europe). Russia) and the Americas, and has grown rapidly in Asia, as well as in the countries of the Global South and the so-called Third World, especially in Latin America, China, South Korea and much of sub-Saharan Africa.

Roots of Christianity

The religious, social, and political climate of I century Roman Judea and its neighboring provinces was extremely diverse and It was constantly characterized by sociopolitical turmoil, with numerous Judaic movements both religious and political. The ancient Roman-Jewish historian Josephus described the four most prominent sects within Second Temple Judaism: the Pharisees, the Sadducees, the Essenes, and a unnamed "fourth philosophy", which modern historians recognize as the Zealots and Hitmen. The I century a. C. and the I century d. C. had numerous charismatic religious leaders who contributed to what would become the Mishnah of Rabbinic Judaism, including the Jewish sages Yohanan ben Zakkai and Hanina ben Dosa. Jewish messianism, and the concept of a Jewish Messiah, has its roots in apocalyptic literature written between the II century B.C.E. C. and the I century B.C. C., which promised a future "anointed" leader (messiah or king) of the Davidic line to resurrect the Israelite Kingdom of God, instead of the foreign rulers of the time.

Judaic Roots

Jesus and his first disciples were Jews. Christianity continued to use the Hebrew scriptures, the Tanakh becoming what is known today as the Old Testament. Accepting many fundamental doctrines of Judaism, such as monotheism, free will and the Messiah, a Hebrew term usually translated as messiah in Spanish, and its equivalent Christ (Cristos "[the] anointed" in Greek).

Relations with the Hellenistic world

The Land of Israel was disputed by the ancient empires, due in large part to its geographic location. It was in the middle of two great trade routes: Egypt and Mesopotamia, Arabia and Asia Minor. Alexander the Great, who defeated the Persians and took over Palestine, when he was received in triumph in Jerusalem, was considered by many the long-awaited messiah. After the death of Alexander (323 BC), Ptolemy I took possession of Egypt, Seleucus I took possession of Assyria and Palestine was again in discord. Remembering Alexander's ideology, which was to unite all humanity under the same civilization with a markedly Greek tonality (fusion called Hellenism), this fusion combined Greek elements with others taken from the conquered civilizations, still varying from region to region. This gave a unity to the Mediterranean basin, which would serve the expansion of the Roman Empire and Christianity through the preaching of the Gospel. For the Jews, Hellenism was a threat to their religion, since Hellenistic philosophy was polytheistic. The pressure of Hellenism was constant and the fidelity of the Jews to their God and their traditions as well. This pressure unleashed a rebellion on the part of the Maccabean Jews, who rebelled against the Hellenism of the Seleucids, who tried to impose their ideals.

Later, the Roman Pompey is presented in 63 BC. C., who takes Palestine deposing the last of the Maccabees, Aristobulus II. Roman policy was tolerant of the religion and customs of the conquered peoples. Herod I, who was not of Jewish ethnicity but an Idumean, although a Jew by religion, did everything possible to introduce Hellenism, to such an extent that, to please the Romans, he tried to place an eagle at the entrance to the Temple of Jerusalem, thereby which provoked a rebellion again, which was put down with two thousand crucifixions.

During this time there were religious groups such as the Pharisees who were a party of the people and did not enjoy the material advantages granted by the Roman regime and watched over the law, believed in the resurrection and in the existence of angels. The Sadducees were the party of the aristocracy, whose interests led them to collaborate with the regime. They were aristocrats and conservatives, they did not believe in the resurrection or in angels. Zealots were militant extremists who were staunchly opposed to the Roman regime. Jesus and the apostles were closer to the Pharisees in doctrine (Jesus did not criticize them for being bad Jews, but because in their eagerness to fulfill the law they forgot human beings). All the parties and all the Jewish sects had something in common, they shared ethical monotheism and eschatological hope.

- Ethical monotheism: Belief in one God. God requires more than an appropriate service, requires "justice" among human beings (although justice interpreted by each group differently) and honor God with all life itself.

- Eschatological hope: They kept Messianic hope, they firmly believed that the day would come when God intervened in the history of Israel and to fulfill a "kingdom of Peace and Justice".

These were the foundations for Christianity, helping it spread throughout the Roman Empire.

Christianity also continued many of the patterns found in Judaism at the time of Jesus, such as the adaptation of the liturgical form of worship in the synagogue to the church or temple; the sentence; the use of the sacred scriptures; a religious calendar; the use of music in hymns and prayer; in addition to disciplines such as fasting. Christians initially adopted the Greek translations of the Jewish scriptures, known as the Septuagint, as their own Bible, later canonizing many of the New Testament books.

Ministry of Jesus

The main sources of information about the life and teachings of Jesus are the four canonical gospels and, to a lesser extent, the Acts of the Apostles and the Pauline epistles. According to the Gospels, Jesus is the Son of God, who was crucified in Jerusalem around the year 30-33. His followers believed that he had risen from the dead and had been exalted by God, announcing the coming of the Kingdom of God..

Early Christianity

Church historians consider early Christianity to begin with the ministry of Jesus (c. 27-30) and end with the First Council of Nicea (325). It is usually divided into two periods: the Apostolic Age (c. 30-100, when the first apostles were still alive) and the Pre-Nicene Period (c. 100-325).

Christianity began among a small number of Jews. About 120 are mentioned in the book of Acts of the Apostles 1:15. In the III century, Christianity grew until it became the dominant congregation in the north of the Mediterranean world. It also spread significantly to the eastern and southern Mediterranean. This section will examine those first 300 years.

The events that occurred in the early years of Christianity are recounted in the book of the Acts of the Apostles. The veracity of some of these accounts is currently questioned due to the great proliferation of false books on the Acts (or Acts) of the Apostles that abounded during early Christianity, but most have maintained the essence of the message, confirmed by archaeological evidence. recent.

The Early Christian Church

The concept of "early Judeo-Christians" is often used when discussing early Christianity. Jesus of Nazareth, his twelve apostles, the elders, and most of his followers were Jews. As well as the 3,000 converts at Pentecost following the crucifixion described in Acts of the Apostles 2, where all Jews, proselytes, and all converts to Christianity were non-Gentiles prior to the conversion of the Roman official Cornelius by Simon Peter in Acts 10, who is considered according to tradition as the first Gentile to be converted to Christianity. The biggest division in Christianity before that time was between Hellenistic and non-Hellenistic Jews or Greek-speaking and Aramaic-speaking Jews (Acts 6). However, after the conversion of Cornelius and his acceptance as a Christian, another group now existed, the Gentile Christians. As an eschatological move, they anticipated that the Gentiles would be transformed to the God of Israel as prophesied by Isaiah in verses 56:6-8. The New Testament does not use the term "gentile-Christian" or "Jewish-Christian". Instead, the Apostle Paul writes against those who, being circumcised, separated from the uncircumcised, or wanted to force uncircumcised adults to be circumcised in order to belong to the Christian community:

For in Christ Jesus, neither circumcision nor uncircumcision have value, but only faith that acts by charity.Epistle to Galatians 5, 6

Circumcised and uncircumcised are generally interpreted as Jews and Greeks respectively, with the latter predominating. However, this may be an oversimplification of the reality in the province of Judea in the I century: there were some Jews who did not They continued to be circumcised, and some Greeks (called proselytes or Judaizers) who did, as well as others such as Egyptians and Ethiopians.

End of the apostolic stage

Around the year 62, the high priest of Judaism, Ananias, had James, the head of the Jerusalem Church, arrested and executed. One of his brothers, Simon, was called to succeed him, but the political situation in Israel was getting worse and the internal conflicts within Judaism were growing every day. It is believed that Paul was beheaded and Peter was crucified upside down in Rome during the persecution by Nero. At the end of the I century, of the original Apostles there lived only John, who had moved to Ephesus, whose church is considered mother of many from Asia Minor and Greece, where Gnostic outbreaks were manifested.

With the emperor Vespasian, Christianity continued to spread, until in the year 90 with the empire under the emperor Nerva (of whom his biographer Xifilino says that "he did not allow anyone to be accused for having observed the ceremonies of the religion Judaica or having neglected the worship of the gods"), John was able to return to Ephesus, and a few years later he died at a very advanced age. With his death (around the year 100) the apostolic stage concluded.

The Didache and other writings of the Apostolic Fathers document the main practices of the early church, for example:

- Clement of Rome, third Episkopo from that city, writes his letter to the Corinthians about the year 96.

- Ignatius of Antioch writes seven letters shortly before his martyrdom in 107.

- Policarpo de Esmirna, disciple of the Apostle John, writes his epistle to the Philippians about 107.

Martyrs of the first century

- They were the first martyr.

- James the Chief Apostle.

- Paul of Tarsus, Apostle.

- Simon Peter, Apostle.

- Onesimo, disciple of Paul

- Ignatius of Antioch, disciple of Peter and first archbishop of Antioch after him.

- Iconium's key, Paul's disciple, which among women received the treatment of prototyping.

- Apollinating from Rávena, bishop.

- Feliciano de Córdoba.

- Pedro de Rates, Bishop of Braga.

- Martian of Syracuse, bishop.

The Apologists

- Justin Martyr, converted from Greek philosophy.

- Athenagoras of Athens

- Apolon

- Antioch Theophile

- Meliton of Sardes

- Lactancio

- Minucio Félix

The Writings

The early Christians produced throughout history many important canons and other literary works described within the organization of the Christian Church. One of the earliest of these is the Didache, which is usually dated to the late first or early second century.

The Records of the Martyrs collect the records of the judicial processes against the Christians, accounts of witnesses and various legends about the first Christian martyrs.

First Heresies

Doctrinal disputes began in the early days of Christianity. The Christian Church organized councils to settle these matters. Councils representing the entire Christian Church were called ecumenical councils. Some groups were rejected as heretics, such as:

- Simonianism

- Nicolaism

- Judaizers

- Gnosticism

- Marcionism

- Montanism

- Adoption

- Mandeanism

- Monarchism

- Nestorianism

- Apollinating

- Arrianism

- Twelveth

Arius (a disciple of Bishop Paul of Samosata) was a leader among Christians who had a very particular understanding of the trinitarian movement, reflecting the natural divinity of Christ. Although many of Arius's writings were destroyed by the Emperor Constantine, we can infer from Athanasius of Alexandria's arguments against Arius some basic concepts of the movement.

Arius's hypothesis was that Jesus was created by God (as in, "There was a time when the Son was not"), and therefore was "secondary" bye bye. His primary proof text was John 17:3. For its part, the position of traditional Christianity was that Jesus was and always has been divine, and that he has a divine nature together with the Father and the Holy Spirit: there is a holy and complete Trinity, likewise homogeneous, that is, the three persons they have the same range.

Gnosticism

A Greek philosophical-religious movement known as Gnosticism had developed around the same time as Christianity. Many followers of this movement were also Christians and taught a synthesis of the two belief systems. This produced a great controversy in the early church.

Gnostic interpretations differed from mainstream Christianity, as orthodox Christians take a literal interpretation of the gospels as correct, while Gnostics tend to read them as allegory.

Competing religions

Christianity wasn't the only religion seeking believers in the I century. Modern historians of the Roman world often take an interest in what they call "mystery religions" or "mystery cults" that began in the last century of the Roman Republic and increased during the centuries of the Roman Empire. Roman authors, such as Livio, comment on the importation of "foreign gods" among the streets of the Roman state. Judaism also welcomes believers and in some cases they actively proselytized. The New Testament reflects a class of people who are referred to as "believers in God" who are thought to be Gentile converts, perhaps those who had not been circumcised; Philo of Alexandria makes explicit the duty of the Jews to receive the new believers.

Manichaeism

Manichaeism was one of the major ancient religions. Although its organized form is almost extinct today, a revival has been attempted under the name of Neo-Manichaeism. However, most of the writings of its founder, the prophet Mani, have been lost. Some scholars argue that his influence continues subtly through Augustine of Hippo, who converted to Christianity from Manichaeism and that his writings continue to be highly influential among Catholic and Protestant theologians (remember that Martin Luther was an Augustinian monk).

The religion was founded by Mani, who is said to have been born in the western Persian Empire and lived from about 210 to 275. The name Mani is more of a title of respect than a personal name. This title was assumed by the founder himself and completely replaced his personal name in such a way that his precise name is not known. Mani was influenced by Mandeism and began preaching at a young age. He declared himself as the Paraclete, as promised in the New Testament: the Last Prophet and Seal of the Prophets who finalized the succession of man guided by God and included figures such as Zoroaster, Hermes, Plato, Buddha and Jesus.

Manichaeism gathers elements of dualist sects, as well as Mithraism. Its believers went to great lengths to include all known religious traditions in their faith. As a result, they preserved many Christian apocryphal works, such as the Acts of Thomas, that would otherwise have been lost. Mani insisted on describing himself as a "disciple of Jesus Christ," but the Orthodox Church rejected him as a heretic.

2nd and 3rd centuries

In the second century AD, numerous scholars began producing writings that help us understand how Christianity developed. These writings can be grouped into two broad categories, works directed at a broad audience of non-believing scholars, and works directed at those who considered themselves Christians. Writings for non-believers were usually called "apologetics" in the same sense as the speech given by Socrates in his defense before the Athenian assembly, called Apology whose word in Greek means "act of speaking in defense of someone"., as these authors are known, make a presentation to educated classes of Christian beliefs, often coupled with an attack on the beliefs and practices of pagans.

Other writings are intended to instruct and admonish fellow Christians. Many writings from this period, however, succumbed to the destruction of the early Catholic Church as heresy, or at variance with its message. Even so, writings such as the Gospel of Thomas in 1945 have been found today.

Origin and evolution of the hierarchy in the Christian Church

In the Church, after the first charismatic authorities in the form of apostles, when they disappeared, hierarchical structures emerged in Christian communities that resemble those of the societies from which they come. Two blocks are distinguished:

- In the communities of Hebrew origin, a school government of elders or presbyters was established, which followed the Jewish tradition, from the most important families or synagogues. This collegiation was in turn presided over by another elder, who in previous times, in Jerusalem became James, the brother of Jesus.

- In the most Gentile communities, the Church was governed by a college of bishops (episcopoiand deacons. The figures of the bishops as prototypes of authority and supervisors of the urban Christian population are those responsible for the administration, prefects and managers, while the deacons are the servants or servants.

This initial double hierarchical structure of Christianity slowly tended towards unification for all the churches, merging the bishops and the presbyters, although for a time they were called interchangeably. Finally, the conditions were established to be able to aspire to bishop, and likewise, for the lower rung of deacons, in their main assistance, administrative and auxiliary tasks of the bishops.

4th century

Many writings from this period were translated into the books of the Nicene and post-Nicene Fathers.

Development of the writing canon

Christians consider that the Bible contains the central nucleus of God's revelation, although the Catholic Church includes, as part of the revelation, Tradition. Over time, the Catholic Church determined which books are part of the Bible canon and which are not, distinguishing between inspired texts and texts not inspired by God. This explains why there are books that emerged in environments close to Christianity that are not considered part of the Bible by Catholics or other Christian groups: A gospel of Saint Thomas, another of Saint Peter, Acts of Saint Paul, others of Saint John., an Apocalypse attributed to Peter.

Originally, there was no official listing of New Testament books. Within primitive Christianity, only the "Scriptures" were taken into consideration, the sacred books of Judaism that were translated into Greek and included in the so-called "Septuagint" Bible. This compilation also included the so-called deuterocanonical books accepted by the Catholic Church and apocryphal by the Protestants. The LXX or Septuagint is what Saint Paul calls the "Scriptures" in his writings.

The process of conformation of what is currently known as the Bible is as follows: The Catholic Church gave the list of books that were considered inspired by the Holy Spirit, which was declared by the authority of the popes Damaso I, Siricius I and Innocent I , and by the following councils and synods: Roman Synod in the year 382, Council of Hippo in the year 393, III Council of Carthage in the year 397 and IV Council of Carthage in the year 419. This was the same new testament that they used Martin Luther and John Calvin.

Old Testament Canon

After Jesus Christ the Jews in Jamnia removed the deuterocanonicals from their Tanakh canon using anti-Christian criteria[citation needed]. This would imply that the Jews no longer had the authority to designate which books were inspired, but rather the early Church had accepted the LXX or Septuagint version. Furthermore, that the version that Saint Paul quotes in his epistles is the Septuagint and it is the one he refers to when he speaks of the Scriptures.

The LXX version (the Old Testament in Greek) is made up of 46 books:

Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, the two books of Samuel (I Samuel and II Samuel), the two books of Kings (I Kings and II Kings), the two books of Chronicles (I Chronicles and II Chronicles), Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Baruch, Ezekiel, Daniel, Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zacharias, Malachi. It also contains the deuterocanonical books of Tobias, Judith, Baruch, Sirach, I Maccabees, II Maccabees, and Wisdom, plus the Greek sections of Esther and Daniel that are not in the proto-canonicals.

The Jews had two canons for their holy books: the short or Palestinian and the long or Alexandrian. The brief is made up of 39 books and is divided into three parts: Torah (The Law), Nevi'im (Prophets) and Ketuvim (writings), the acronym of these three parts results in the word Tanak or Tanaj. These 39 books are known as the "proto-canonical" books. The Palestine canon was made in Jamnia, and is based on a Hebrew translation of the Bible made after Christ; They are not the original texts but a translation.

The Jews in Alexandria believed that God did not stop communicating with his people even outside of Israel, and enlightened his children in the new circumstances in which they found themselves.[<citation needed]

Jesus should have used the short or Palestinian canon, but the apostles, in taking the Gospel throughout the Roman Empire, used the Alexandrian canon. The early Church received this canon consisting of 46 books.

From the year 393 different councils were specifying the list of the "canonical" for the Christian Church. These were: the Council of Hippo in the year 393, the Council of Carthage in the years 397 and 419, the Council of Florence in the year 1441 and the Council of Trent in the year 1546.

Protestants admit as sacred books the 39 books of the Hebrew canon that was established after Christ by the Jews, without any Christian intervention. The first to deny the canonicity of the deuterocanonical books was Carlstadt in 1520, and later Luther in 1534 and Calvin in 1540. Although Luther seems to contradict himself, for in his Commentary on Saint John he said: "We are obliged to admit of papists that they have the Word of God, that we have received it from them, and that without them we would have no knowledge of it". This "papist" pronounced that the 73 books that make up the Old and New Testaments are revelation.

Bishop Melito of Sardis recorded the first known list of the Septuagint in AD 170. C. It contained 45 books, it seems that one is missing since the book of Lamentations was considered as part of Jeremiah.

New Testament

The New Testament is made up of 27 books, and is divided into four parts: the Gospel or Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, the Epistles, and the Apocalypse. Of these books, seven were called into question: Epistle to the Hebrews, Epistle of James, Second Epistle of Peter, Second Epistle of John, Third Epistle of John, Epistle of Judas, and Revelation. The doubt that they were inspired was based on their authenticity.

In the primitive Church, the rule of faith was found in the oral teaching of the apostles and the first evangelizers. As time passed, that generation began to die and the urgency was felt to record in writing the teachings of Jesus Christ and the most outstanding features of his life. This is the cause of the writings of the Gospels. On the other hand, according to the problems that were arising, the apostles fed their faithful spiritually through letters. This was the origin of the Epistles.

Late I and early <span style="font-variant:small-caps;text" century II, the collection of writings varied from church to church. Also in the II century, the ideas of the heretic Marcion, who claimed that only the Gospel of Luke and the ten epistles of Paul they had a divine origin; and Montanism, which sought to introduce Montano's writings as holy books, hastened the determination of the New Testament Canon.

In the time of Saint Augustine, the councils of Hippo in 393 and of Carthage in 397 and 419 (known as the African councils) recognized the 27 books, as well as the council of Trullo (Constantinople, in 692) and the Florentine Council in 1441.

Protestantism renewed old doubts and excluded some books. Dr. Martin Luther rejected Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation. At the Council of Trent held in 1546, the complete list of the New Testament was officially and dogmatically presented. The theological explanation was that the books had to be revealed by the Holy Spirit and faithfully transmitted by him. The main practical criteria were four: its apostolic origin or of the apostolic generation, its orthodoxy in doctrine, its liturgical use and its generalized use.

4th and 5th centuries: officialization of Christianity in the Roman Empire

Influence of Constantine I

Emperor Constantine I together with Licinius, promulgated the Edict of Milan in 313, decreeing freedom of worship throughout the Empire and thus ending the persecution of Christians.

It is difficult to discern how much Christianity Constantine embraced at this time, but his accession was a turning point for the Christian Church. He financially supported the Church, built several basilicas, granted privileges (for example, exemption from certain taxes) to the clergy He promoted Christians to some high offices and returned confiscated property. Constantine played an active role in the leadership of the Church. In 316, he acted as a judge in a North African dispute over the Donatist controversy. More significantly, in 325 he convened the Council of Nicaea, the first ecumenical council. In this way, he established a precedent for the emperor as responsible before God for the spiritual health of his subjects and, therefore, with a duty to uphold orthodoxy. He was to enforce the doctrine, eradicate heresy, and defend ecclesiastical unity.

The successor to Constantine's son, his nephew Julian, under the influence of his advisor Mardonius, renounced Christianity and embraced a Neoplatonic and mystical form of paganism, which shocked the Christian establishment. He began reopening pagan temples, modifying them to resemble Christian traditions, such as the episcopal structure and public charity (previously unknown in Roman paganism). Julian's brief reign ended when he was killed in battle with the Persians.

Arianism

Arius (250-336) proposed that Jesus and God were very separate and different entities: Jesus was closer to God than any other human, but he was born human, and had no previous existence, therefore he was not God; a person similar or similar to God, without necessarily being the same. On the other hand, God had always existed. Arius felt that any attempt to acknowledge the divinity of Christ blurred the line between Christianity and pagan religions. If Christianity recognized two separate gods, the Father and Jesus, it would become a polytheistic religion.

Nicene Creed

Within the Council of Nicaea, the assembly composed a creed to express the faith of the Christian Church declaring that Jesus was "of one substance" with God the Father.

Caesaropapism

Caesaropapism began when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, causing two effects: Church support for the State and vice versa, State support for the Church, which led to Caesaropapism, which supported the theory of the divine origin of kings and gave them absolute power over religion and government at the same time.

Revival of paganism by Rome in the fourth century

Struck by these developments, the Emperor Julian (called "the Apostate" because of his rejection of Christianity and his conversion to Mithraism and Neoplatonism) attempted to restore the former status among the empire's religions by eliminating the privileges given by ancient Roman emperors such as Constantine (tax exemption among Christian clergy, for example), forbidding different Christian denominations from persecuting each other and bringing back archbishops who had been outlawed by Arianism, encouraging Judaism and a luck of neopaganism.

Nicene Christianity opposes Byzantine emperors

- St. Athanasius exiled from his archbishop in Alexandria at least five times for opposing arianism.

- Saint John Chrysostom (patriarch of Constantinople) died in exile for criticizing the imperial court in his homilies.

Christianity becomes state religion

Julian's opposition was short-lived, emperors such as Constantine II repelled Julian's actions and encouraged the growth of Christianity. This state of affairs was finally reinforced by a series of decrees (such as the Edict of Thessalonica) by the Nicene Emperor Theodosius I, beginning in February 381, and continuing through his reign. Thus, at the end of the IV century, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire.

Other material from this era

- Ambrose of Milan (archbishop and saint).

- Pentarchy, organization of the church in 5 patriarchates.

First Christological controversies

Christological controversies include examination of questions such as: was Christ divine, human, a created angelic being, or beyond a simple classification into one of these categories? Did Christ's miracles really change physical reality or were they just symbolic? Did the body of Christ really rise from the dead or was the risen Christ a supernatural being not limited by physical laws?

- Arrio, Athanasius of Alexandria

- Diodoro de Sicilia, Teodoro de Mopsuestia

- Cyril of Alexandria and Nestorio

- The Council of Antinstorian Ephesus and the Council of Antimonophytic Chalcedon in 451.

- The search for reconciliation and heresy of one will (monotelism, the belief that Jesus Christ had a [divine] will as opposition to the two wills, one divine and one human). The Fifth Ecumenical Council condemned monotheism and failed to achieve the reconciliation desired by the Byzantine emperor.

5th century

The conversion of the Mediterranean world

- Agustín de Hipona

- Jerónimo de Estridón

Development of Christianity outside the Mediterranean world

Christianity was not restricted to the Mediterranean basin and its surroundings; At the time of Jesus a large proportion of the Jewish population lived in Mesopotamia, outside the Roman Empire, especially in the city of Babylon, where much of the Talmud was developed.

- Saint Thomas Christians are established in India possibly beginning in 52 and certainly until before 325.

- Christianity in Ethiopia.

- Christianity in the Sassanian Empire

- Christianity reaches the British islands.

- Christianity arrives in Ireland (traditionally given in 432) and the evolution of Celtic Christianity.

- Irish missionaries and the spread of Christianity to Britain and Northern Europe.

- The establishment of papal authority in Ireland after the Great Schism.

- Nestorian Christians travel along the silk road to establish a community in the Tang Dynasty with capital in Chang'an, building the Daqin Pagoda in 640.

Late Middle Ages (476–842)

The transition to the High Middle Ages was a gradual and localized process. Rural areas became centers of power, while urban areas were in decline. Although more Christians remained in the East (Greek areas), important developments took place in the West (Latin areas), each taking distinctive forms. The bishops of Rome, the popes, were forced to adapt to drastically changing circumstances. Maintaining only a nominal allegiance to the emperor, they were forced to negotiate balances with the "barbarian rulers" of the former Roman provinces. In the East, the Church maintained its structure and character and evolved more slowly.

Western Missionary Expansion

The gradual loss of dominance of the Western Roman Empire, replaced by the Foederati and Germanic kingdoms, coincided with early missionary efforts in areas not controlled by the declining empire. As early as the V, missionary activities from Roman Britain to Celtic areas (Scotland, Ireland and Wales) produced rival early traditions of Celtic Christianity, which were later reintegrated under the Church from Rome. The Christian saints Patrick, Columba, and Columbanus were leading missionaries of the day in northwestern Europe. The Anglo-Saxon tribes that invaded southern Britain some time after the Roman abandonment were initially pagan, but were converted to Christianity by Augustine of Canterbury on the mission of Pope Gregory the Great. It soon became a missionary center, and missionaries such as Wilfredo, Wilibrordo, Lulo, and Bonifacio converted their Saxon relatives to Germania.

The largely Christian Gallo-Roman inhabitants of Gaul (present-day France and Belgium) were invaded by the Franks at the turn of the V century . The native inhabitants were persecuted until the Frankish king Clovis I converted from paganism to Catholicism in 496. Clovis insisted that his nobles follow his example, strengthening his newly established kingdom by uniting the faith of the rulers with that of the ruled. After the rise of the Frankish kingdom and the stabilization of political conditions, the western part of the Church increased missionary activities, supported by the Merovingian dynasty as a means to pacify troublesome neighboring peoples. Following Wilibrordo's founding of a church in Utrecht, negative reactions ensued when the pagan Frisian king Radbod destroyed many Christian centers between 716 and 719. In 717, the English missionary Boniface was sent to Wilibrordo's aid, reestablishing churches in Friesland and continuing missions in Germania. In the late VIII century, Charlemagne resorted to mass slaughter to subdue the pagan Saxons. and force them to accept Christianity by force.

The Rise of Islam

Islam emerged on the Arabian peninsula in the 7th century century with the appearance of the Prophet Muhammad. In the VII and VIII centuries , the Muslims managed to expand their empire by seizing territories that ranged from the Iberian Peninsula in the west to India in the east, many of which were territories with a Christian majority.

Orthodox Caliphate (632–661)

During the orthodox caliphate (rashidun), while considered "People of the Book" in the Islamic religion, Christians under Muslim rule were subject to the status of dhimmi (along with Jews, Samaritans, Gnostics, Mandaeans and Zoroastrians), which was inferior to that of Muslims. Christians and other religious minorities thus faced discrimination and religious persecution, since they were prohibited from proselytizing (for Christians, it was prohibited evangelize or spread Christianity) in the lands invaded by Muslim Arabs on pain of death, they were prohibited from carrying weapons, practicing certain professions and forced to dress differently to distinguish themselves from Arabs. Under Islamic law (sharīʿa), non-Muslims were required to pay the taxes of the yizia and jarach, along with the heavy ransoms that Muslim rulers periodically charged Christian units to finance military campaigns, all of which brought a significant share of revenue to Islamic states and, in turn, reduced many Christians to poverty, and these financial and social hardships forced many Christians to convert to Islam. Christians who could not pay these taxes were forced to hand over their children to Muslim rulers as payment, who sold them as slaves to Muslim households where they were forced to convert to Islam.

According to the tradition of the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Muslim conquest of the Levant was a relief to Christians oppressed by the Western Roman Empire. Michael the Syrian, Patriarch of Antioch, later wrote that the Christian God had "raised from the south to the sons of Ishmael to deliver us for them out of the hands of the Romans." Various Christian communities in the regions of Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Armenia held grudges against the rule of the Western Roman Empire or with that of the Western Roman Empire. Thus they preferred to live in more favorable economic and political conditions as dhimmi under the Muslim rulers. However, modern historians also acknowledge that the Christian populations living in the lands invaded by the armies Muslim Arabs between the VII and X d. suffered religious persecution, religious violence and martyrdom at the hands of Arab Muslim officials and rulers on multiple occasions; many were executed under the Islamic death penalty for defending their Christian faith through dramatic acts of resistance such as refusing to convert to Islam, repudiation of the Islamic religion and subsequent reconversion to Christianity, and blasphemy towards Muslim beliefs.

Umayyad Caliphate (661–750)

According to the Ḥanafī school of Islamic law (sharīʿa), the testimony of a non-Muslim (such as a Christian or a Jew) was not considered valid against the testimony of a Muslim in legal matters or civilians. Historically, in Islamic culture and traditional Islamic law, Muslim women have been prohibited from marrying Christian or Jewish men, while Muslim men have been allowed to marry Christian or Jewish women. Muslims had the right to convert to Islam or any other religion, whereas a murtad, or an apostate from Islam, faced severe punishment or even hadd, which could include the penalty of Islamic death.

In general, Christians under Islamic rule could practice their religion with some notable limitations derived from the apocryphal Covenant of Omar. This treaty, supposedly promulgated in the year 717 d. C., prohibited Christians from publicly displaying the cross on church buildings, summoning congregants to prayer with the ringing of bells, rebuilding or repairing churches and monasteries after they had been destroyed or damaged, and imposed other restrictions. related to occupations, clothing, and weapons. The Umayyad Caliphate persecuted many Christian Berbers in the 7th and VIII d. C., who gradually converted to Islam.

In Umayyad al-Andalus (in the Iberian Peninsula), the Mālikī school of Islamic law was the most widespread. The martyrdoms of forty-eight Christian martyrs that took place in the emirate of Córdoba between 850 and 859 d. C. are collected in the hagiographic treatise written by the Christian scholar and Iberian Latinist Eulogio de Córdoba. The martyrs of Córdoba were executed under the government of Abderramán II and Mohamed I, and Eulogio's hagiography describes in detail the executions of martyrs for capital violations of Islamic law, including apostasy and blasphemy.

Abbasid Caliphate

Eastern Christian scientists and scholars of the medieval Islamic world (particularly Jacobite and Nestorian Christians) contributed to Arab Islamic civilization during the reign of the Umayyads and Abbasids, translating works of Greek philosophers into Syriac and, later, Arabic. They also excelled in philosophy, science, theology, and medicine. Likewise, the personal physicians of the Abbasid caliphs were often Assyrian Christians, such as those of the Bakhtishu dynasty, which served the caliphate for a long time.

The Abbasid Caliphate was less tolerant of Christianity than the Umayyad Caliphs. However, Christian officials continued to be employed in the government, and Christians from the Church of the East were often tasked with translating philosophy and Greek mathematics. Al-Jahiz's writings attacked Christians for being too prosperous, suggesting that they were able to ignore even state restrictions. By the end of the century IX, the Patriarch of Jerusalem Theodosius, wrote to his colleague the Patriarch of Constantinople Ignatius that "they are just and do us no harm or show us any violence".

Elijah of Heliopolis, transferred to Damascus from Heliopolis (Baalbek), was accused of apostasy from Christianity after attending a party held by a Muslim Arab, and was forced to flee Damascus for his hometown, returning eight years later, where he was recognized and imprisoned by the "eparch", probably the jurist al-Lait ibn Sa'd. After refusing to convert to Islam under torture, he was brought before the Damascene emir and relative of the caliph al-Mahdi (r 775-785), Muhammad ibn-Ibrahim, who promised good treatment if Elías converted. Faced with his repeated refusals, Elías was tortured and beheaded and his body burned, dismembered and thrown into the Crisorraso (Barada) river in the year 779. d. C.

According to the Synaxarion of Constantinople, the hegumen Michael of Zobe and thirty-six of his monks from the monastery of Zobe, near Sebasteia (Sivas), were killed in an assault on the community. The perpetrator was the 'emir of the Agarenes', 'Alim', probably Ali ibn-Sulayman, an Abbasid ruler who ravaged Roman territory in AD 785. C.. Bacchus the Younger was beheaded in Jerusalem in AD 786-787. Bacchus was a Palestinian, whose family, having been Christian, had been converted to Islam by his father. Bacchus, however, remained a Crypto-Christian and undertook a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, after which he was baptized and entered the monastery of Mar Saba. The reunion with his family led to their conversion to Christianity, as well as the trial and execution of Bacchus for apostasy under the ruling emir Harthama ibn A'yan.

Following the sack of Amorius in 838, hometown of Emperor Theophilus (r. 829-842) and his Amorian dynasty, the caliph al-Mu'tasim (r. 833-842) took more than forty Roman prisoners, who were taken to the capital, Samarra, where, after seven years of theological debates and repeated refusals to convert to Islam, they were sentenced to death in March 845 under Caliph al-Wáthiq (r. 842-847). A generation later they were venerated as the 42 martyrs of Amorio. According to his hagiographer Euodius, probably writing a generation after the event, the defeat at Amorius was to be blamed on Theophilus and his iconoclasm. According to some later hagiographies, including that of one of several Middle Byzantine writers known as Michael the Sinkellos, among the forty-two were Callistos, the doge of the theme of Colonea, and the heroic martyr Theodore Karteros.

During the 10th century phase of the Arab-Byzantine wars, Roman victories over the Arabs led to mob attacks on Christians believed to be sympathetic to the Roman state. According to Bar Hebraeus, the catholicus of the Church of the East, Patriarch Abraham III (r. 906-937), wrote to the Grand Vizier that "We Nestorians are friends of the Arabs and pray for their victories". Nestorians, "who have no king but the Arabs", he contrasted it with that of the Greek Orthodox Church, whose emperors, according to him, "had never stopped making war on the Arabs". Between 923 and 924 AD. In BC, several Orthodox churches were destroyed by mob violence in Ramla, Ashkelon, Caesarea Maritima, and Damascus. In each case, according to the Melkite Arab chronicler Eutychius of Alexandria, the Caliph al-Muqtádir (r. 908-932) contributed to the reconstruction of ecclesiastical assets.

Byzantine Iconoclasm

After a series of severe military setbacks against Muslims, iconoclasm emerged in the provinces of the Byzantine Empire in the early 8th century span>. In the 720s, the Byzantine Emperor Leo III the Isauric prohibited the pictorial representation of Christ, saints, and biblical scenes. In the Latin West, Pope Gregory III held two synods in Rome and condemned Leo's actions. The Byzantine iconoclastic council, held at Hieria in AD 754. C., ruled that the sacred portraits were heretical. The iconoclastic movement destroyed much of the early artistic history of the Christian Church. The iconoclastic movement was later defined as heretical in 787 AD. C. under the Council of Nicea II (the seventh ecumenical council), but had a brief revival between 815 and 842 d. c.

High Middle Ages (800–1299)

Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was a period of intellectual and cultural renaissance in literature, the arts, and biblical studies during the 8th centuries and IX under the rule of the Carolingian dynasty, mainly during the reigns of the Frankish kings Charlemagne, founder and first emperor of the Carolingian Empire, and his son Ludovico Pío. To deal with problems of illiteracy among the clergy and court scribes, Charlemagne founded schools and brought to his court the most learned men from all over Europe.

Monastic reform

From the 6th century century, most monasteries in the Catholic West belonged to the Benedictine order. Due to stricter adherence to a reformed Benedictine rule, Cluny Abbey became the main recognized center of Western monasticism from the turn of the century X. Cluny created a large federated order in which the administrators of the subsidiary houses acted as deputies of the abbot of Cluny and answered to him. The Cluniac spirit exerted a revitalizing influence on the Norman Church, in its heyday from the second half of the X to the early 10th century. XII.

The next wave of monastic reform came with the Cistercian movement. The first Cistercian abbey was founded in 1098, in the Cîteaux abbey. The dominant note of Cistercian life was the return to the literal observance of the Benedictine rule, rejecting the developments of the Benedictines. The most striking feature of the reform was the return to manual labor, and especially to field work. Inspired by Bernardo de Claraval, the main builder of the Cistercians, they became the main force for the advancement and technological diffusion of medieval Europe. By the end of the 12th century, Cistercian houses numbered 500, and at their height in the XV, the order claimed to have about 750 houses. Most of them were built in desert areas, and they played an important role in bringing those isolated areas of Europe into economic cultivation.

A third level of monastic reform was the establishment of mendicant orders. Commonly known as "friars," mendicants live under monastic rule with traditional vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, but emphasize preaching, missionary activity, and education, in an isolated monastery. Beginning in the 12th century, the followers of Francis of Assisi instituted the Franciscan Order, and later Saint Dominic began the Dominican Order.

Growing tensions between East and West

Tensions in Christian unity had begun to become apparent as early as the 4th century. These concerned two basic issues: the nature of the primacy of the Bishop of Rome, and the theological implications of adding a clause to the Nicene Creed, known as the Filioque clause. These doctrinal questions were first openly discussed in the patriarchate of Photius (858-867 and 877-886). The Eastern Churches considered Rome's conception of the nature of episcopal power to be directly opposed to the essentially conciliar structure of the Church and therefore considered both ecclesiologies to be antithetical.

Another issue that became a great irritation to Eastern Christendom was the gradual introduction into the Nicene Creed in the West of the Filioque clause—meaning "and of the Son"—as in "the Holy Ghost... proceeding from the Father and the Son", when the original creed, sanctioned by the councils and still used today by the Orthodox, simply says "the Holy Spirit,... who proceeds from the Father". The Eastern Church argued that the phrase had been added unilaterally and therefore illegitimate, since the East had never been consulted. In addition to this ecclesiological issue, the Eastern Church also considered the Filioque clause unacceptable for reasons dogmatic.

Schism of Photius

In the IX century, a controversy arose between Eastern (Byzantine, Greek Orthodox) and Western (Latin, Roman Catholic) which was precipitated by Pope Nicholas I's opposition to the Byzantine Emperor Michael III's appointment of Photius I (a layman) as Patriarch of Constantinople replacing Ignatius. Photius was denied an apology by the Pope for earlier points of contention between East and West. Photius refused to accept the supremacy of the pope in Eastern affairs or to accept the Filioque clause. The Latin delegation at the council of his consecration pressured him to accept the clause in order to secure his support. The dispute also concerned the eastern and western ecclesiastical jurisdictional rights in the Bulgarian church. Photius made a concession on the question of jurisdictional rights relative to Bulgaria, and the papal legates settled for his return of Bulgaria to Rome. This concession, however, was purely nominal, since Bulgaria's return to the Byzantine rite in 870 had already ensured it an autocephalous church. Without the consent of Boris I of Bulgaria, the papacy could not assert any of his claims.

Nicholas I excommunicated Photius in 867, declaring Ignatius the legitimate patriarch. This action together with the fact that Nicholas I meddled, sending his own missionaries, in the Christianization of Bulgaria that was being carried out by the Byzantines, caused Photius, supported by the emperor, in a synod also held in the year 867 in Byzantium, he excommunicated the pope and the entire western church, also taking the opportunity to reject the inclusion of the Filioque clause in the Nicene Creed. That same year, the influential courtier Basil I usurped the imperial throne from Miguel III and reinstated Ignatius as patriarch. After Ignatius' death in 877, Photius was reappointed, but an agreement between him and Pope John VIII prevented a second schism. Photius was deposed again in 886 and spent his last years in retirement condemning the West for his alleged heresy.

The central problem was the papal claim to jurisdiction in the East, not the accusations of heresy. The schism arose largely as a struggle for ecclesiastical control of the southern Balkans and a clash of personalities between the leaders of the two sees, both elected in 858 and whose reigns ended in 867. The Phocian schism arose This differed from what happened in the XI century, when the authority of the Pope was questioned because he had lost it due to heresy. The Photian schism helped polarize East and West for centuries, partly because of the false but widespread belief in a second Photian excommunication. This idea was eventually disproved in the 20th century, which has helped to rehabilitate Photius somewhat in the West.

Spread of Christianity in Central and Eastern Europe

- The Holy Cyril and Methodius translate the Bible and the liturgy into the ancient ecclesiastical Slave in the centuryIX.

- The Christianization of the Kyiv Rus in 988 spreads Christianity among the Eastern Slavs, establishing the Eastern Christian identity of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia.

Schism between East and West (1054)

The East-West Schism, also known as the "Great Schism", separated the Church into Western (Latin) and Eastern (Greek) branches, i.e. Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. It was the first great division since certain Eastern groups had rejected the decrees of the Council of Chalcedon (see Eastern Orthodox Churches) and it was much more significant. Although normally dated to 1054, the East-West Schism was actually the result of a long period of rift between Latin and Greek Christendom over the nature of papal primacy and certain doctrinal issues regarding the Filioque clause, but it intensified. based on cultural, geographic, geopolitical and linguistic differences.

The schism took a long time to develop; the main themes were the role of the pope in Rome and the Filioque clause. The "official" schism occurred in 1054, by the Roman excommunication of the Patriarch of Constantinople Michael I Cerularius, followed by the Constantinopolitan excommunication of the pope's representative. The excommunications were mutually rescinded by the pope and the patriarch of Constantinople in the 1960s, but even so the schism has not been completely eliminated.

The Great Schism occurred between Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. Both traditions emphasize apostolic succession, and both historically claim to be the only legitimate descent from the early Church. Each one, moreover, asserts that the tradition of the apostles is more correctly maintained and that the other has deviated. Roman Catholics often refer to themselves simply as "Catholics," which means "universal," and maintain that they are also Orthodox. The Eastern Orthodox refer to themselves simply as "Orthodox" which means "right worship," and they also call themselves Catholics. Initially, the schism was primarily between the East and the West, but today both congregations are spread throughout the world. They still refer to each other in those terms for historical reasons.

Claim of the investitures

The quarrel of the endowments, also called the quarrel of the secular endowments, was the most important conflict between the secular and religious powers that took place in medieval Europe. It began as a dispute in the 11th century 11th century between the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII over who should appoint bishops (investment). The end of lay investiture threatened to undermine the power of the Holy Roman Empire and the ambitions of the European nobility. Bishoprics being mere lifetime appointments, a king could better control his own powers and income than those of hereditary nobles. Better yet, he could leave the bishop's office vacant and continue to collect the revenue, theoretically in trust for the new bishop, or assign a bishopric as payment to a useful nobleman. The Catholic Church wanted to end the lay investiture to put an end to this and other abuses, to reform the episcopate and provide better pastoral care. Pope Gregory VII issued the Dictatus Papae, which declared that only the pope could appoint bishops. The rejection of the decree by Henry IV led to his excommunication and a ducal revolt. Finally, Henry IV received acquittal after a dramatic public penance, although the Great Saxon Revolt and the conflict over the investiture continued.

A similar controversy arose in England between King Henry I and Saint Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, over investiture and episcopal vacancy. The English dispute was resolved with the London Concordat (1107), in which the king renounced his claim to invest the bishops, but continued to require an oath of allegiance. This was a partial model for the Concordat of Worms (Pactum Calixtinum), which settled the imperial investiture controversy with a compromise allowing secular authorities some measure of control, but conceding the selection of the bishops to their cathedral canons. As a symbol of commitment, both the ecclesiastical and lay authorities invested the bishops with the ecclesial staff and ring, respectively.

The Crusades

Broadly, the Crusades (1095-1291) refer to the Papacy-sponsored European Christian campaigns in the Holy Land against Muslims to reconquer the region of Palestine. There were other Crusading expeditions against Islamic forces in the Mediterranean, mainly in southern Spain, southern Italy, and the islands of Cyprus, Malta, and Sicily. The papacy also sponsored numerous crusades against the pagan peoples of northeastern Europe to subdue and forcibly convert them to Christianity, against their political enemies in Western Europe and against heretical or schismatic religious minorities within European Christendom.

The Holy Land had been part of the Roman Empire, and therefore of the Byzantine Empire, until the Muslim Arab invasions of the 7th centuries and VIII. Thereafter, Christians were generally allowed to visit holy sites in the Holy Land until 1071, when the Seljuk Turks closed down Christian pilgrimages and attacked the Byzantines, defeating them at the Battle of Manzikert. Emperor Alexios I asked Pope Urban II for help against Islamic aggression. He probably expected the Pope to give him money to hire mercenaries. Instead, Urban II appealed to the knights of Christendom in a speech delivered at the Council of Clermont on November 27, 1095, combining the idea of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land with that of waging a holy war against the unfaithful.

The First Crusade captured Antioch in 1099 and then Jerusalem. The Second Crusade took place in 1145, when Edessa was captured by Islamic forces. Jerusalem remained until 1187 and the Third Crusade, after the battles between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin. The Fourth Crusade, launched by Innocent III in 1202, aimed to recapture the Holy Land, but was soon subverted by the Venetians, who used the troops to sack the Christian city of Zara. Innocent excommunicated the Venetians and the Crusaders. Eventually the Crusaders reached Constantinople, but due to fighting that broke out between them and the Byzantines, the Crusaders sacked Constantinople and other parts of Asia Minor, instead proceeding to the Holy Land, effectively establishing the Latin Empire of Constantinople in Greece. and Asia Minor. This was effectively the last crusade sponsored by the papacy; later crusades were privately sponsored. Five crusades to the Holy Land, culminating in the 1219 siege of Acre, essentially ended the Western presence in the Holy Land. Thus, although Jerusalem held for nearly a century and other Near Eastern strongholds would remain in Christian possession for much longer, the crusades in the Holy Land failed to finally establish permanent Christian kingdoms.

On the other hand, the crusades in southern Spain (the Reconquista), southern Italy and Sicily ended up causing the disappearance of Islamic power in those regions; The Teutonic Knights expanded Christian domains in eastern Europe in the so-called Livonian Crusade, and subjugated and forcibly converted the pagan Slavs of modern East Germany in the Wendic Crusade. Much less frequent crusades within Christendom, such as the Albigensian crusade against the Cathars of southern France, combined with the inquisition that followed, achieved their goal of maintaining doctrinal unity.

Christian Church and State in the Western Middle Ages

- Pope Gregory VII

- Medieval Inquisition and Inquisition

Late Middle Ages

- The Conciliation Movement

- Christian humanity

- End of the Byzantine Empire in 1453

- Witch hunt

Modern and Contemporary Age

Ancient America

- Conquerors

- Santería, a fusion of Catholicism with religious traditions of West Africa originally brought among slaves.

The Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation

- The role of Juan Gutenberg's printing press in the dissemination of the reformist texts.

- Martin Luther

- Juan Calvin and Calvinism

- Bible King James

- Council of Trent

- Thirty Years War

- Inquisition

- Radical Reform and Anabaptists

- Amish, Mennonites

Rise of the religious denominations of Protestantism

- Discuss the uprising of the greatest religious denominations after the Protestant Reform and the challenges faced by Catholicism.

- Baptist churches

- Presbyterian churches

- Church of England

- John Wesley and Methodism

- Francis Asbury, Thomas Coke and American Methodism

- First Great Wake

- Pentecostalism

- Luteranism

- Sisters of Christ

- The Puritans

- The Quakers

- Non-conformists

- The English Civil War

- Congress of Religions, 1893

19th century

- Catholic revival in Romantic Europe

- Anglo-Catholics or Oxford Movement in the Church of England

- Missionaries and Colonialism

- Friedrich Schleiermacher and Liberal Christianity

Anticlericalism and Atheistic Communism

In some revolutionary movements the Catholic Church was seen as an ally with the overthrown rulers, for which reason it was persecuted. For example, after the French Revolution and the Mexican Revolution there were actions of persecution and reprisals against Catholics. In the context of the communist world, Karl Marx condemned religion as the "opium of the people" [1] and the Marxist-Leninist governments of the 20th century were often atheistic; of these, only Albania officially declared itself an atheist state.

20th century

Christianity in the 20th century is characterized by accelerated fragmentation. The century saw the rise of both liberal and conservative groups, as well as a general secularization of Western society. The Catholic Church instituted many reforms to modernize itself. Missionaries made forays into the Far East, establishing a following in China, Taiwan, and Japan. At the same time, persecution in communist Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union brought many Orthodox Christians to Western Europe and the United States, increasing contact between Western and Eastern Christianity. In addition, ecumenism grew in importance, beginning with the Edinburgh Missionary Conference in 1910, although it is criticized that Latin America has been excluded because Protestant preaching in Latin America has often been anti-Catholic.

Catholic reforms

- Second Vatican Council

- Ecumenical initiatives

- Anatemas (excommunion) of the Great Schism revoked by the Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople (1960).

- Pope John Paul II

Other moves

Another movement that grew in the 20th century was Christian Anarchism, which rejects the Christian church, state or any power other than God's. They also believe in absolute non-violence. Leo Tolstoy's book The Kingdom of God is within you published in 1894 was the catalyst for this movement.

In the 1950s, there was an evangelical expansion in America. The post-World War II prosperity experienced in the United States also had religious effects, termed "morphological fundamentalism." The number of Christian temples increased, and the activities of the evangelical Churches grew expansively.

Within Catholicism, Liberation Theology (L.T.) formally emerged in the 1960s in Latin America, as a response to the malaise produced by the oppression and poverty characteristic of the peoples of this region. The Catholic Church does not officially accept the postulates of the TL, due to a possible close relationship with Marxism, although liberation theologians deny such a relationship, although they do accept the existence of concepts such as class struggle. However, the Catholic Church does accept some postulates of the same T.L. especially in relation to the need for freedom of the peoples in the world, but also generalizing the idea to freedom from other sins as well.

Another notable development in the 20th century within Christianity was the rise of Pentecostal movements. Although its roots date back to before the year 1900, its actual birth is commonly attributed to the 20th century. Sprouting from Methodist roots, they rose from meetings at an urban mission on Azusa Street in Los Angeles. From there they spread throughout the world, carried by those who experienced what they believe to be miraculous movements of God in that place. Pentecostalism, which started the charismatic movement within established denominations, continues to be a major force in Western Christianity.

Modernism and the Fundamentalist Reaction

The radical implications of the scientific and cultural influences of the Enlightenment were felt in the Protestant Churches, especially in the 19th century; liberal Christianity sought to unite the Churches together with the broad revolution that modernism represented. In doing so, new critical approaches to the Bible were developed, new attitudes became evident about the role of religion in society, and new thinking began to question the almost universally accepted definitions of orthodox Christianity.

In reaction to these events, Christian fundamentalism was a movement that rejected the radical influences of philosophical humanism as affecting Christianity. Targeting especially critical approaches to Bible interpretation, and trying to block inroads made into their Christian churches by atheistic scientific presumptions, fundamentalists began to appear in various denominations as numerous independent movements of resistance to the abrupt changes in historic Christianity.. Over time, evangelical fundamentalist movements had split into two branches, one labeled fundamentalist, while a more moderate movement preferred the label evangelical. Although both movements originated first in the Anglo-Saxon world, most Evangelicals are found everywhere.

The Rise of the Evangelical Movement

In the United States and in the rest of the world, there has been a marked growth of the evangelical sector of the Protestant denominations, especially in those that identify exclusively as evangelical, and a decline of those Churches identified with more liberal currents. In the interwar period (1920s), liberal Christianity was the fastest growing sector, something that changed after the Second World War, when more conservative leaders arrived in the ecclesiastical structures.

The evangelical movement is not an entity. Evangelical Churches and their followers cannot be easily classified. Most are not fundamentalists, in the strict sense that some give that term, although many continue to refer to themselves as such.

However, the movement has managed to manage in an informal way, to reserve the name Evangelical for those groups and believers who adhere to a profession of Christian faith that they consider historical, a Evangelical i>paleo-orthodoxy, as some call it. Those who call themselves "moderate evangelicals" point to staying even closer to those "historical" Christian foundations, and "liberal evangelicals" they do not apply this name to themselves in defining terms of their theology, but of their "progressive" in the civic, social or scientific perspective.

There is a great diversity of evangelical communities around the world, the ties between them are only apparent (several local and global organizations link them, but none to all), but most agree on the following beliefs: a " high esteem" of the Scriptures, belief in the deity of Christ, in the Trinity, in salvation by grace through faith, in the physical resurrection of Christ, to name just a few.

Evangelism in the 10/40 Window

Evangelicals define and prioritize efforts to reach the "unreached" late 20th century and early XXI by focusing on countries between 10° north and 40° south latitudes. This area is largely dominated by Muslim nations, many of which do not allow missionaries of other religions into their countries.

The spread of secularism

In Western Europe there is a general move away from religious observance and belief in Christian teachings and towards secularism. The "secularization of society", attributed to the time of the Renaissance and the following years, is largely responsible for this movement. For example, a study by Gallup International Millennium shows that only a sixth of Europeans attend regular religious services, less than half rate God as "most important," and only 40% believe into a "personal God". Although the vast majority consider that they "belong" to a religious denomination. The numbers show that the "de-Christianization" of Europe has slowly started to move in the opposite direction.

In North America, South America and Australia, the other three continents where Christianity is the dominant professed religion, religious observance is higher than in Europe. At the same time, these regions are often seen by other nations as conservative and "Victorian" in their social urbanity.

South America, historically Catholic, has experienced a great evangelical infusion in the last 80 years due to the influence of evangelical missionaries. For example, in Brazil, the largest country on the continent, it is the country with the largest number of Catholics in the world and at the same time the one with the largest number of Evangelicals. Some of the largest congregations in the world are in Brazil; also in Colombia, a country with a Catholic tradition is undergoing dramatic changes in its society since evangelical Christianity is growing exponentially, only in the capital city Bogotá are the churches in which they congregate in groups of 1000, 3000, 10000 and up to 50000.[citation needed]

Historiography

Historians of Christianity were:

- Eusebius of Cesarea

- Gregorio de Tours

- César Baronio

- Isaac Casaubon

- Edward Gibbon

Contenido relacionado

Annex: Municipalities of the province of Toledo

Sweden

Peseta