History

The history is the narration of the events of the past; generally those of humanity, although, it may also not be human-centric. It is also an academic discipline that studies such events. Science or academic discipline is also called historiography to distinguish it from history understood as the objective facts that occurred. It is a social science due to its classification and method; but, if it does not focus on the human, it can be considered as a natural science, especially in an interdisciplinarity framework; In any case, it is part of the classification of science that includes the previous two, that is, a factual science (also called factual).

Its purpose is to find out the events and processes that occurred and developed in the past and interpret them according to criteria of the greatest possible objectivity; although the possibility of fulfilling such purposes and the degree to which they are possible are in themselves objects of study of historiology or theory of history, such as epistemology or scientific knowledge of history.[citation required]

The person in charge of the study of history is called a historian. The professional historian is thought of as the specialist in the academic discipline of history, and the non-professional historian is often referred to as a chronicler.

Etymology

The word history derives from the Greek ἱστορία (read history, translatable as «investigation» or «information», knowledge acquired by investigation), from the verb ἱστορεῖν («to investigate »). From there it passed into Latin historia, which in Old Castilian evolved into estoria (as attested by the title of the Estoria de España by Alfonso X the Wise, 1260-1284) and was later reintroduced into Spanish as a cultism in its original Latin form.

The remote etymology comes from the Proto-Indo-European *wid-tor- (from the root *weid-, «to know, to see» —hypothetical construction—) also present in the Latin words idea or vision, in the Germanic words wit, wise or wisdom, Sanskrit veda, and Slavic videti or vedati, and in other languages of the Indo-European family.

The ancient Greek word ἱστορία was used by Aristotle in his Περὶ τὰ ζῷα ἱστορίαι (read Peri ta zoa jistória, Latinized Historia animalium, translatable as History of the animals [the Greek title is plural and the Latin is singular]). judge"). Uses of ἵστωρ can be found in the Homeric hymns, Heraclitus, the oath of the Athenian ephebes, and in Boeotian inscriptions (in a legal sense, meaning similar to "judge" or "witness"). The aspirated feature is problematic, and does not occur in the Greek cognatic word εἴδομαι ("to appear"). The form ἱστορεῖν ("to inquire"), is an Ionic derivation, which spread first in classical Greece and later in the Hellenistic civilization.

Definition

In turn, the past itself is called «history», and one can even speak of a «natural history» in which humanity was not present,[citation required] used in opposition to social history, to refer not only to geology and paleontology, but also to many other natural sciences—the boundaries between the field to which this term traditionally refers and that of prehistory and history. archeology are imprecise, through paleoanthropology—, and which is intended to be complemented with environmental history or ecohistory, and updated with the so-called "Great History".

This use of the term "history" makes it equivalent to "change over time" In this sense, it opposes the concept of philosophical equivalent to essence or permanence (which allows us to speak of a natural philosophy in classical texts and in today, especially in Anglo-Saxon academic circles, as equivalent to physics). For any field of knowledge, you can have a historical perspective —the change— or a philosophical one —its essence. In fact, this can be done for history itself (see historical time) and for time itself. In this sense, all past in relation to the present alludes to time and its chronology, and therefore to have history.[citation required]

Study

As science

Within the popular division between sciences and letters or humanities, history tends to be classified among the humanistic disciplines along with others social sciences (also called human sciences), or it is even considered as a bridge between both fields, by incorporating the methodology of these to those.

Not all historians accept the identification of history with a social science, considering it a reduction in its methods and objectives, comparable with those of art if they are based on the imagination (a position adopted to a greater or lesser extent by Hugh Trevor -Roper, John Lukacs, Donald Creighton, Gertrude Himmelfarb or Gerhard Ritter). Supporters of its scientific status are most of the historians of the second half of the XX century and of the XXI (including, among the many who have made explicit their methodological concerns, Fernand Braudel, E. H. Carr, Fritz Fischer, Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Bruce Trigger, Marc Bloch, Karl Dietrich Bracher, Peter Gay, Robert Fogel, Lucien Febvre, Lawrence Stone, E. P. Thompson, Eric Hobsbawm, Carlo Cipolla, Jaume Vicens Vives, Manuel Tuñón de Lara or Julio Caro Baroja). Many of them did it from a multidisciplinary perspective (Braudel combined history with geography, Bracher with political science, Fogel with economics, Gay with psychology, Trigger with archaeology), while the others mentioned did so in turn with the previous ones and with others, such as sociology and anthropology. This is not to say that they have reached a common position among themselves on the methodological consequences of history's aspiration to scientific rigor, much less that they propose a determinism that (at least since the Einsteinian revolution at the beginning of the century XX) do not even propose the so-called hard sciences.

For their part, the historians less inclined to consider their activity scientific do not defend a strict relativism that would make knowledge of history and its transmission totally impossible, and in fact, in a general way, they accept and submit to institutional mechanisms, academics and scientific practice existing in history and comparable to those of other sciences (research ethics, scientific publication, peer review, debate and scientific consensus, etc.).[citation required]

The use that history makes of other disciplines as instruments to obtain, process and interpret data from the past allows us to speak of auxiliary sciences of history with a very different methodology, whose subordination or autonomy depends on the purposes to which they are applied. apply.[citation required]

As an academic discipline

The record of annals and chronicles was in many civilizations a trade linked to a public institutional position, controlled by the State. Sima Qian (called father of History, in Chinese culture) inaugurated in that civilization the bureaucratized official historical records (century II BC). The criticism of the Muslim Ibn Khaldun (Muqaddima —Prolegomena to Universal History—, 1377) of the traditional way of making history had no immediate consequences, and was considered a precedent. of the renewal of the methodology of history and of the philosophy of history that did not begin until the XIX century, fruit of the evolution of historiography in Western Europe. Meanwhile, the official Castilian and Indies chroniclers gave way in illustrated Spain in the XVIII century to the founding of the Royal Academy of the history; Similar institutions exist in other countries.

The teaching of history in compulsory education was one of the bases of nation building since the XIX century, simultaneous process to the proliferation of history chairs in universities (initially in the faculties of Letters or Philosophy and Letters, and over time, in their own faculties or of Geography and History —disciplines whose proximity scientific and methodological is a characteristic of the French and Spanish academic tradition—) and the creation of all kinds of public and private institutions (historical clubs or historical societies, very usually medievalist , responding to their own historicism of romantic taste, engaged in the search for elements of national identification); as well as publications dedicated to history.

In high school in most countries, history programs were designed as an essential part of the curriculum. In particular, the aggregation of history present in the French lycées since 1830 acquired over time a social prestige incomparable with similar positions in other educational systems and which characterized the elitism of the secular republican school until the end of the XX century.

This institutionalization process was followed by the specialization and subdivision of the discipline with different temporal biases (of questionable application outside of Western civilization: ancient, medieval, modern, contemporary history -the latter two, common in French historiography or Spanish, are not usually subdivided in Anglo-Saxon historiography: modern era—), spatial (national, regional, local, continental history —of Africa, Asia, America, Europe, Oceania—), thematic (political, military, institutional, economic and social history, social movements and political movements, civilizations, women, daily life, mentalities, ideas, culture), stories sectors linked to other disciplines (history of art, music, nature, religions, law, science, medicine, economics, political science, political doctrines, technology). ology), or focused on any type of particular issue (history of electricity, democracy, the Church, unions, operating systems, the —literary forms of the Bible—, etc). Given the atomization of the field of study, different proposals have also been made that consider the need to overcome these subdivisions with the search for a holistic perspective (history of civilizations, total history or universal history) or its reverse approach (microhistory); without forgetting the new academic and interdisciplinary field of Big History as "the attempt to understand in a unified way, the History of the Cosmos or Universe, the Earth, Life and Humanity", covering history from the Big Bang to the History of the Present World. Examines long-lasting times using a multidisciplinary approach based on the combination of numerous disciplines of science and the humanities that study the past, the Historical-Sciences, and explores human existence in the context of a broader panorama, which in relation to the present alludes to time and chronology, being taught in universities and schools.

The National History Award (from Chile —biannually, to a personality— and from Spain —to a work published each year—) and the Prince of Asturias Award for Social Sciences (to a personality in the field of history, the geography or other social sciences) are the highest recognitions of historical research in the Spanish-speaking world, while in the Anglo-Saxon world there is one of the versions of the Pulitzer Prize. The Nobel Prize for Literature, which can go to historians, was only awarded twice (Theodor Mommsen, in 1902, and Winston Churchill, in 1953). From a perspective more typical of the current consideration of history as a social science, the Nobel Prize in economics was awarded to Robert Fogel and Douglass North in 1993. On the other hand, the Pfizer Prize of the History of Science Society was established in 1958. The prize consists of a medal and a cash amount. This award is given in recognition of an extraordinary book on the history of science. Every year, a hundred authors compete for this prize, which is considered the most important for books on the history of science.

The International Prize for Historical Sciences is the most prestigious international prize in History awarded by the International Committee of Historical Sciences (International International Committee of Historical Sciences / Comité international des sciences historiques), the international association of Historical Sciences founded in Geneva on May 14, 1926, which since 2015 awards the CICH International History Prize, Jaeger-LeCoultre, to the " historian who has distinguished himself in the field of history by his works, publications or teaching, and has contributed significantly to the development of historical knowledge". Considered the "Nobel Prize" in Historical Sciences, the CISH Council jury, which has 12 members from different countries, selects the winner from a pool of excellent and highly qualified candidates. Only the collective members of the CISH (its national committees or its international affiliated organizations) can present candidates.

Historian

Perspectives: justification, importance and objective

Nor should the supposed teleological ends of man in history be confused with the ends of history, that is, the justification of history itself as a memory of humanity. History, being a social science, cannot be abstracted from why it is in charge of studying social processes: explaining the facts and events of the past, either through knowledge itself, or because they help us understand the present.

Cicero baptized history as teacher of life, and like him Cervantes, who also called it mother of truth.

Benedetto Croce highlighted the strong involvement of the past in the present with his all history is contemporary history. History, by studying the events and processes of the human past, is useful for understanding the present and raising possibilities for the future.

Sallustio went so far as to say that among the different occupations that are exercised with ingenuity, the memory of past events occupies a prominent place due to its great utility.

A widely spread cliché (attributed to Jorge Santayana) warns that peoples who do not know their history are doomed to repeat it, although another cliché (attributed to Karl Marx) indicates that when it repeats itself once as a tragedy and the second time as a farce.

The radical importance of this is based on the fact that history, like medicine, is one of the sciences in which the research subject coincides with the object to be studied. Hence the great responsibility of the historian: history has a projection into the future due to its transforming power as a tool for social change; and to the professionals who manage it, the historians, what Marx said about the philosophers is applicable (until now they have been in charge of interpreting the world and what it is about is transforming it). No From another perspective, however, a disinterested inquiry is intended for objectivity in historical science. Although getting to know the facts as they were, as Leopold Ranke claimed, is impossible, yes, it is an imperative for historical research to get as close as possible to that objective, and also to do so with a perspective that places the facts in their context, so that the understanding of what really happened; and although it is inevitable that biases of all kinds alter the way in which such an understanding is produced, at least be aware of what they can be and to what degree they work.

Branches

Historiography

Historiography is the set of techniques and methods proposed to describe the historical events that occurred and were recorded, understood as the science that is in charge of the study of history. The correct praxis of historiography requires the correct use of the historical method and submission to the typical requirements of the scientific method. Historiography is also called the literary production of historians, and the schools, groups or trends of historians themselves.

The identification of the concept of history with the written narration of the past produces, on the one hand, its confusion with the term historiography (history is simultaneously called the object studied, to the science that studies it and to the document resulting from that study); and on the other, it justifies the use of the term prehistory for the period before the appearance of writing, reserving the name history for the later period.

According to this restrictive use, the majority of humanity remains out of history, not so much because they do not have personal access to reading and writing (illiteracy was the common condition of the vast majority of the population, even for the ruling classes, up to the printing press), but because those reflected in the historical discourse have always been very few, and entire groups remain invisible (the lower classes, women, the discrepant who cannot access the written record), with which the reconstruction of the vision of the defeated and history from below has been the object of concern of some historians.

The same thing occurs with a large number of peoples and cultures (those considered primitive cultures, in a terminology now outdated from ancient anthropology) that have no history. The topic idealizes them by considering that they are happy peoples. They enter it when their contact, usually destructive (acculturation), with civilizations (complex societies, with writing) occurs. Even at that time they are not properly the object of history but of protohistory (history made from the written sources produced by what are generally their colonizing peoples in opposition to the indigenous peoples). However, regardless of whether historians and anthropologists ideologically have an ethnocentric tendency (eurocentric, sinocentric or indigenist >) or, on the contrary, multiculturalist or cultural relativist, there is the possibility of obtaining or reconstructing a reliable account of the events that affect a human group using other methodologies: archaeological sources (material culture) or oral history. To a large extent, this difference is artificial, and not necessarily novel: Herodotus himself cannot but use this type of documentary sources when writing what is considered the first History, or at least he coined the term, in Greece in the V century a. C. so that time does not destroy the memory of the actions of men and that the great undertakings undertaken, whether by the Greeks or by the barbarians, do not fall into oblivion; it also gives reason for the conflict that put these two towns in the fight. Thus begins his work entitled Ἱστορίαι (read históriai, literally «investigations», «explorations», Latinized Historiae —«Historias», in the plural—), seminal for historical science, and which is usually called in Spanish The nine books of history. The fight mentioned is the medical wars and the barbarians, Persians.

Historiology

The historiology or «theory of history» is the set of explanations, methods and theories about how, why and to what extent certain types of historical events and sociopolitical trends occur in certain places and not in others. The term was introduced by José Ortega y Gasset and the DRAE defines it as the study of the structure, laws and conditions of historical reality.

Branches of other related sciences

Philosophy of history

The philosophy of history should not be confused with historiology or historiography, from which it is clearly separated. The philosophy of history is the branch of philosophy concerned with the meaning of human history, if it has one. Originally, he speculated if a teleological end to its development was possible, that is, he wonders if there is a design, purpose, guiding principle or finality in the process of human history. Currently, there is more discussion about the function of historical knowledge within knowledge and its implications. There has also been a discussion about whether the object of history should be a historical truth, it should be, or if history is in some sense cyclical or linear and historical development departs indefinitely from the starting point. It has also been discussed whether it is possible to speak of the idea of positive progress in it.

Areas of study by geographic region

Universal history

Traditional Periodization

There is no universal agreement on the periodization of history, although there is an academic consensus on the periods of the history of Western civilization, based on the terms initially coined by Cristóbal Celarius (Ancient, Middle and Modern Ages), which it put the classical Greco-Roman world and its Renaissance as the determining facts for the division; and that it is currently of general application. The accusation of Eurocentrism that is made to such periodization does not prevent it from being the most used, because it is the one that responds precisely to the development of the historical processes that produced the contemporary world.

Regarding the division of prehistoric time into the Stone Age and the Metal Age, it was proposed in 1836 by the Danish archaeologist Christian Jürgensen Thomsen.

Technological evolution presents two great caesuras in the past of humanity: the Neolithic revolution and the industrial revolution, which allows us to speak of three great periods: the one characterized by the exclusivity of hunter-gatherer societies, the pre-industrial and the industrial (Sometimes the adjective post-industrial is used for the most recent period of history.)

The problem with any periodization is to make it coherent in synchronic and diachronic terms, that is to say: that it is valid both for the passage of time in a single place, and for what happens at the same time. same time in different spatial fields. Fulfilling both requirements is difficult when the phenomena that cause the beginning of a period in one place (especially the Near East, Central Asia or China) take time to spread or arise endogenously in other places, which in turn may be more or less close and connected (like Western Europe or sub-Saharan Africa), or more or less distant and disconnected (like America or Oceania). To respond to all this, periodization models include intermediate terms and periods of overlap (juxtaposition of different characteristics) or transition (gradual appearance of novelties or mixed characteristics between the period that begins and the one that ends). The teaching of history is often helped by different types of graphic representation of the succession of events and processes in time and space.

| Prehistory | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stone Age | Age of Metals | |||||||

| P a l e o l í t i c o | Mesoly | N e o l í t i c | Age of Copper | Age of Bronce | Age of the Lord | |||

| P a l e o l í t i c o i n f e r i o r | P a l e o l í t i c o m e d | Upper Palaeolithic | Epi-Paleolithic | Proto-neolithic | ||||

| History of Europe | ||||||||||||

| Protohistory | Old age | Age | 18th century | Modern Age | 18th century | Contemporary Age | ||||||

| Classical antiquity | Late age | High Age | Lower Middle Ages | |||||||||

| Middle Ages | Crisis | centuryXVI | XVII century | centuryXIX | centuryXX | centuryXXI | ||||||

- Prehistory. From the appearance of man (difference of different species of gender Homo, subtribution hominine, superfamily Hominoida, order of the primates), of uncertain dates, more than two million years ago; until the appearance of the writing, around the fourth millennium a. C.. It is considered an academic field or specialty very linked to Archaeology.

- Paleolithic (etymologically) Old Stone Ageby the carved stone. The most decisive facts are those linked to human evolution, in the physical, and to primitive cultural evolution (use of tools and fire and development of different types of primitive social collaboration and conduct; notably language). Social groups would not exceed the size of hordes, with a population density less than one inhabitant per square kilometer. The economy was limited to a relationship predator with the environment (hull, fishing and harvesting), which did not prevent a remarkable impact (first humanization the natural landscape and extinctions caused by the pressure of human activity in the ecosystems where it is introduced.

- Lower Palaeolithic. First modes of legal size of instruments (Olduvayense or mode 1 and Achelense or mode 2), associated with fossil remains of hominids: Australopitecus, Homo habilis and Homo ergaster (South-East Africa), Homo erectus (extended throughout the Old Continent); Homo antecessor and Homo heidelbergensis (specifics from Europe—atapuerca’s foundation).

- Paleolithic medium. Linked to changes in material culture (Musteriense or mode 3) and in the species of hominids (Man of Neanderthal in Europe, Homo sapiens archaic in Africa—Men of Kibish—), from 13,000 years ago to approximately 35,000 years ago.

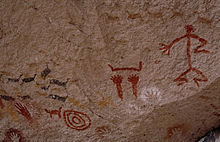

- Upper Palaeolithic. Linked to material culture associated with Homo sapiens modern: the mode 4 (Auriñaciense, Gravetiense, Solutrense, Magdaleniense—in Europe—, Clovis and Monte Verde—in America, where for the first time there are hominids—); from 35 000 years to about 10,000 years ago. There are no significant changes for paleoanthropology in the fossil record; variations between different groups are much more subtle: those traditionally studied by physical anthropology and known as human racesand that modern population genetics study with renewed methodologies (molecular genetics). Along with the paleo-linguistics it intends to rebuild primitive migrations.

- Mesoly/Epipaleolithic/Protoneolithic. Transition period, linked to the changes that led to the end of the last glacier. From the 10th millennium to C. to the 8th millennium B.C., approximately. In areas where it meant a transition to the neolyticism is called mesoly, while in the rest, in which it only means a phase of continuation of the paleolithic, is called epipaleolithic.

- Neolithic (etymologically "new age of stone", by the rotten stone: mode 5). From the 8th millennium B.C. to the 4th millennium B.C. approximately. Its beginning in each area is linked to the development of the so-called Neolytic Revolution: replacement of the economy (hull, fishing and harvesting) economy (agriculture and cattle breeding), which extraordinarily increased population density (limited growth—old demographic regime) and impact on the environment. Appearance of ceramics, substitution of nomadism by sedentarism (stable settlements or villages). It took place from the 8th millennium B.C. in the fertile growth of the Middle East, and spread to the north of Africa and Europe (in Spain from the 6th millennium B.C.) and Asia. The emergence of agriculture and livestock was endogenous in other parts of the world (safely in America, less clearly in other areas).

- Age of Metals. From the fourth millennium to C. (or later, according to the area), which although it is an already historical era in the Near East, is still prehistoric in most parts of the world. Technological innovations of gradual diffusion (metalur, wheel, plow, candle). Some villages are walled and increase in size until they become cities. The economy and society becomes more complex (experience, long-distance trade, specialization of work, social stratification with a leading elite characterized by the display of wealth in the form of weapons and funeral monuments). Transit to history will be given when the formation of complex societies (civilizations) with institutionalized state and religion is completed, which will produce writing.

- Calcolytic or Age of Copper (III millennium B.C. approximately, in Western Europe).

- Age of Bronze (II millennium B.C. approximately, in Western Europe).

- Age of Iron (I millennia a. C. approximately, in Western Europe, until romanization).

- Paleolithic (etymologically) Old Stone Ageby the carved stone. The most decisive facts are those linked to human evolution, in the physical, and to primitive cultural evolution (use of tools and fire and development of different types of primitive social collaboration and conduct; notably language). Social groups would not exceed the size of hordes, with a population density less than one inhabitant per square kilometer. The economy was limited to a relationship predator with the environment (hull, fishing and harvesting), which did not prevent a remarkable impact (first humanization the natural landscape and extinctions caused by the pressure of human activity in the ecosystems where it is introduced.

- History. Development of writing as a result of the appearance of the first states. IV millennium B.C. in Sumeria.

- Protohistory. Period of overlap: the civilizations that develop writing leave written record not only of themselves, but of other peoples who have not. Usually the colonizing peoples are the ones that give historical testimony of their relationship to the indigenous peoples (e.g., the pre-Roma peoples).

- Old age

- Birth of civilization in the Old Near East (sometimes called Early antiquity). First states (times, cities-states, hydraulic empires) in Mesopotamia (Sumeria, Acad, Babylon, Assyria), Ancient Egypt, Levante Mediterranean (Fenicia, Ancient Israel) and the rest of the Eastern Mediterranean (anatholic civilizations—hitites—, and egeas—minoica and micenica—); with very little relation to those nuclei in India (doxy culture of the Indo-Chine valley),

- Classical antiquity: Between the centuryVIIIa. C. and the centuryII. Restricted validity to the Greek and Roman civilizations, characterized by classical culture (the term of great ambiguity, which in its spatial and temporal aspect can be considered extended to the entire Near East by the Hellenism behind the Empire of Alexander the Great and the Western Mediterranean by the Helenized Roman Empire; or restricted to the classical period of Greek art — centuryVa. C. and centuryIVa. C.—; or even tighter than century of Pericles — mid-century AthensV—), and early concepts of freedom, democracy and citizenship that were paradoxically based on the submission of other peoples and the intensive use of the slave labour force. Both civilizations counted their eras from the time of the centuryVIIIa. C. (the first Olympic or the foundation of Rome, respectively). Simultaneously, the Persian Empire developed, which occupies the intermediate space and puts in contact the Mediterranean civilizations with Asian civilizations, especially the Hindu, while the civilizations of the Far East, such as the Chinese, develop in a practically independent way, and the Americans in total disconnection.

- Late age: Restricted validity to the West is a transition period, from the crisis of the third century to Carlomagno or the arrival of Islam to Europe (sixteenth centuryVIII), in which the Roman Empire falls into decay and suffers the impact of German invasions, new monotheistic religions (Christianism and Islam) are imposed as dominant religions and the mode of slave production is replaced by feudal mode of production. In the East survives the Reviving Byzantine Empire.

Two Greek warriors in singular combat. After them there are chariots of war. Fragment of a crather of black figures, Selinunte, centuryVIa. C. (contemporaneous to the reforms of Clístenes). The military equipment for fighting body-to-hand (casco, spear) is similar to that used by the hoplitas, but they fight grouped in phalanges, and the shield will be designed to protect both the liner and the one who takes it..

Sarcophagus Ludovisi, about 250. The Roman legions struggle against the gods, which in the following centuries (period of barbaric invasions) will contribute decisively to both the continuity and the Fall of the Roman Empire, after which some of the most important Germanic kingdoms of the High Middle Ages will be established.

Chac Mool (Chichén Itzá, Mayan city founded in the centuryVI). Mesoamerican civilizations developed a peculiar culture linked to the ritualized war between rival cities-states, which included the sacrifice of prisoners to guarantee the cosmological order, in addition to a anthropophagia of debated consideration.

- Age: Restricted validity to the West, from the fall of the Roman Empire of the West (sixteenth century)Vuntil the fall of the Roman Empire of the East (sixteenth century)XV). In such a prolonged period there were very complex dynamics, which have little to do with the topics of isolation, immobile and obscurantism with which it was defined from the perspective of the modernitythat undervalued it as a parenthesis of backwardness and discontinuity between a mythified old age and its rebirth in the modern.

- High Age: centuryV to the centuryX. One Dark age due to the scarcity of written sources, due to the backwardness of urban life and the breakdown of political power that characterize feudalism. The Church, especially through the monastic, becomes the only continuity of intellectual tradition. The nobility and the clergy, linked familiarly, are the Gentlemen. that exercise political, social and economic power over the peasants subjected to servitude. Castles and monasteries are imposed in a landscape of forests, baldness and small villages almost incommunicado.

- Lower Middle Ages: From the centuryXI to the centuryXV. Sometimes it is restricted to the centuryXIV and the centuryXVsuch as Crisis of the Middle Ages or Crisis of the Fourteenth Century;XI to the centuryXIII as Plenitude of the Middle Ages. It produces a Urban revolution and an increase in the commercial and artisanal activity of an emerging bourgeoisie, while strengthening the power of the feudal monarchies. Universal powers (Pontified and Empire) face and fall into crisis. The Crusades demonstrate the capacity of European expansion towards the east of the Mediterranean, while the Christian kingdoms of the northern peninsula were imposed in Al-Ándalus (Muslim Spain). The medieval university reworked ancient knowledge through scholastics (revolution of the 12th century). In the final centuries the features that will characterize the entire period of the Old Regime: an economy in transition from feudalism to capitalism, a stallary society and an authoritarian monarchy in transition to the absolute monarchy.

- Modern Age: From the middle or the end of the centuryXV in the middle or the end of the centuryXVIII. (For the English speakers, Early Modern Times, that is, "First Modern Age" or "Modern Age"). It is taken as milestones that mark its beginning the Print, the taking of Constantinople by the Turks or the discovery of America; as a final, the French Revolution, the Independence of the United States of America or the Industrial Revolution. It is for the first time a period of almost global validity, since for the majority of the world (with the only partial exception of China or Japan—which after first contacts opt to close to the foreign influence to a greater or lesser extent—or of conditons of America, Africa and Oceania—colonized in the centuryXIX—), it meant the imposition of Western civilization and the so-called world economy. It began with the era of the discoveries and expansion of the Spanish and Portuguese empire, while the world of ideas was experiencing the innovations of the Renaissance, the Protestant Reform and the Scientific Revolution; counterbalanced by the Counter-Reformation and the Baroque. While in the France of Louis XIV succeeded absolutism, in other parts of North-West Europe the first bourgeois revolutions that challenged the Old Regime (Netherlands revolution, English revolution) and in the south and east of the continent a process of refeudalization was observed. The axis of civilization shifted from the Mediterranean basin to the Atlantic Ocean. The crisis of the 17th century and the Westphalia treaties rebuilt a new European equilibrium that prevented Spanish or French hegemonies, and which remained during the centuryXVIIIintellectually characterized by the Enlightenment. Throughout the period the modern concepts of nation and state are being developed.

- Contemporary Age. From the middle or the end of the centuryXVIII to the present. (For the Anglo-speaking Later Modern Timesthat is, "Second Modern Age" or "Modern Age Tardy". An initial of revolutions (industrial revolution, bourgeois revolution and liberal revolution) ended the Old Regime and took place in the second half of the centuryXIX the triumph of capitalism that extends with imperialism to the whole world, while being answered by the workers' movement. Napoleonic wars gave way to a period of British hegemony during the Victorian era. The beginning of the demographic transition (first in England, soon afterwards on the European continent and later on in the rest of the world) produces a real demographic explosion that radically alters the social and man's balance with nature, especially from the second industrial revolution (pass of the was coal and steam machine to the was oil and explosion engine and the was electricity). The first half of the centuryXX. It was marked by two world wars and a period of wars in which the liberal democracies facing the 1929 crisis are challenged by the Soviet and fascist totalitarianisms. The second half of the centuryXX. was characterized by the balance of terror between the two superpowers (the United States and the Soviet Union), and the decolonization of the Third World, in the midst of regional conflicts of great violence (such as the Arab-Israeli) and an acceleration of technological innovation (third industrial revolution or scientific-technical revolution). Since 1989, the fall of the Berlin wall and the disappearance of the socialist bloc led to the present world of the centuryXXI chaired by the globalization of both the economy and the political, military and ideological presence (soft power) of the only superpower, as well as its allies (classical powers—European Union, Japan—), partners or potential rivals (emerging powers—China) and opponents (minor powers, such as some Islamic countries, and sometimes expressed movements in terrorism—11-S).

National History

Contenido relacionado

1982

Condition

Oware

![Chac Mool (Chichén Itzá, ciudad maya fundada en el siglo VI). Las civilizaciones mesoamericanas desarrollaron una cultura peculiar ligada a la guerra ritualizada entre ciudades-estado rivales, que incluía el sacrificio de los prisioneros para garantizar el orden cosmológico, además de una antropofagia de debatida consideración.[36]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Maya_Chac_Mool_by_Luis_Alberto_Melograna.jpg/141px-Maya_Chac_Mool_by_Luis_Alberto_Melograna.jpg)