Historiography

The term historiography comes from «historiographer», and this from the Greek ἱστοριογράφος (historiográphos), being a conjunction of ἱστορία —history (or "history")— and γράφος (gráphos), from the root of γράφειν/gráphein ("to write"); which means "the one who writes (or describes) the story".

Historiography is the art of writing it, but it is also the science that studies history. The emphasis on its condition as "art" (τέχνη tékhnē) or "science" (ἐπιστήμη epistḗmē) is one of the most important objects of methodological debate among historians, with abundant participation of intellectuals who have reflected on it, given its central position in culture. For a part of them, one cannot even speak of "history" singular, since the narrative condition of its products turns them into "stories" in the plural. For most contemporary historians, on the other hand, the scientific condition of history is inalienable, or at least the aspiration to such a condition ("science under construction"), and even The vision that does not perceive both features (science and art) as strictly incompatible but rather as complementary is widespread.

The different disciplines that are used for historiographical study are grouped under the name of «historiographical sciences and techniques» (paleography -which would include epigraphy and papyrology-, documentation or documentary sciences, sigilography, diplomatics, codicology, numismatics, etc.).

A historian specializing in historiography is called a historiographer.

Historiography as meta-history

If history is a science whose object of study is the past of humanity, an issue in which most but not all historians agree, it must be submitted to the scientific method, which although it cannot be applied in all extremes of the experimental sciences, it can do so at a level comparable to the so-called social sciences.

A third confluent concept when defining history as a source of knowledge is the «theory of history», which can also be called «historiology» (a term coined by José Ortega y Gasset). Its role is to study "the structure, laws and conditions of historical reality", while "historiography" is, at the same time: the story itself, the art of writing it, and the scientific study of its sources, products and authors.

It is impossible to end the polysemy and the overlapping of these three terms, but simplifying as much as possible it can be defined:

- history as the facts of the past,

- Historiography as the science of history,

- Historiology as his epistemology.

The philosophy of history is the branch of philosophy concerned with the meaning of human history, if any. It speculates on a possible teleological end to its development, that is, it questions whether there is a design, purpose, guiding principle, or finality in the process of human history. It should not be confused with the three previous concepts, from which it is clearly separated. If its object is the truth or what should be, if history is cyclical or linear, or there is the idea of progress in it, these are matters alien to history and historiography itself, which this discipline deals with. An intellectual approach that does not contribute much to understanding historical science as such is the subordination of the philosophical point of view to historicity, considering all reality as the product of a historical evolution: that would be the place of historicism, a philosophical current that can be extended to other sciences, such as geography.

Once the merely nominal issue has been cleared up, the analysis of written history, the descriptions of the past, therefore remains for historiography; specifically of approaches to narrative, interpretations, worldviews, use of evidence or documentation, and methods of presentation by historians; and also the study of these same subjects and objects of science.

Historiography, more simply, is the way in which history has been written. In a broad sense, historiography refers to the methodology and practices of history writing. In a more specific sense, it refers to writing about history itself.

Historiographic sources and their treatment

To investigate and interpret societies, historians turn to historical sources, that is, to written or material testimonies, which allow historical events to be reconstructed.

It is important to distinguish the raw material of the historians' work (primary source) from the semi-finished or finished products (secondary source and even tertiary source). A primary source comes directly from the time being investigated, or what is the same, they must have been produced parallel and contemporaneously to the facts. They are first-hand testimonies, that is, laws, treaties, memories etc A secondary source has been produced after the period studied. Secondary sources are books, articles, maps, etc., that rework information obtained with primary sources.

It is equally important to denote the difference between source and document and the study of documentary sources: their classification, priority and typology (written, oral, archaeological); their treatment (meeting, criticism, contrast), and maintaining the respect due to the sources, fundamentally with their faithful appointment. The originality of the work of historians is a delicate matter.

Historiography as historiographic production

The term Historiography is equivalent to each part of the historiographical production, that is, to the set of writings by historians about a specific topic or historical period. For example, the phrase "historiography on daily life in Japan in the Meiji era is very scarce" means that there are few books written on the subject because up to now it has received no attention from historians, not because its object of study is not very relevant or because there are few documentary sources that provide historical documentation to do so.

The word historiography is also used to talk about the group of historians of a nation, for example, in sentences similar to this: «Spanish historiography opened its arms and its archives from the 1930s to the French and Anglo-Saxon Hispanists, who They renewed their methodology.

It is necessary to differentiate the two terms used above: «historiographical production» and «historical documentation», although in many cases it coincides that historians use as historical documentation precisely the previous historiographical production.

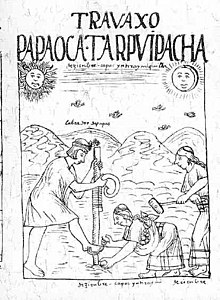

For example: in addition to a set of archival documents from the Casa de Contratación in Seville that were produced perhaps only to keep accounts; or some archaeological material found in an excavation in Peru, and that was deposited without intention that no one would find it; an Americanist historian will have to use the Very Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies, which was written by Bartolomé de las Casas with an undoubted historical desire, as well as for the purpose of defending an interest or its own point of view. With the latter we see another insurmountable characteristic of history that distinguishes it as a science: no historian, no matter how objective he claims to be, is oblivious to his own interests, ideology or mentality, nor can he escape his particular point of view. At most you can try intersubjectivity, that is, take into account the existence of multiple points of view. In the case that serves as an example, contrasting the sources of Bartolomé de las Casas with the other voices that were heard in the Valladolid Junta, among which that of his rival Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda stood out, or even with the so-called "vision of the vanquished", which is rarely preserved, but sometimes it is, as is the case with the New Chronicle and Good Government of the Inca Guaman Poma de Ayala

Reflection on the possibility or impossibility of an objective approach leads to the need to overcome the opposition between objectivity (that of a non-existent "pure" science that is not contaminated with the scientific one) and subjectivity (implicated interests, ideology and limitations of the latter) with the concept of intersubjectivity, which forces us to consider the task of the historian, like that of any scientist, as a social product, inseparable from the rest of human culture, in dialogue with other historians. and with the whole society.

Historiography and perspective: the object of history

History has no choice but to follow the trend towards specialization that any scientific discipline has. Knowledge of all reality is epistemologically impossible, although the effort of transversal, humanistic knowledge of all parts of history is required of whoever truly wants to have a correct vision of the past.

So history must be segmented not only because the historian's point of view is contaminated with subjectivity and ideology, as we have seen, but because he must necessarily opt for a point of view, just like a scientist, if he wants to observe his object, you must choose whether to use a telescope or a microscope (or, less crudely, what kind of lens to apply). With the point of view, the selection of the part of historical reality that is taken as an object is determined, and that will undoubtedly give as much information about the object studied as about the motivations of the historian who studies. This biased vision can be unconscious or conscious, assumed with more or less cynicism by the historian, and it is different for each era, for each nationality, religion, class or area in which the historian wants to place himself.

The inevitable loss that segmentation entails is compensated by the confidence that other historians will make other selections, always biased, which must be complemented. The claim to achieve a holistic perspective, as claimed by the total history or the history of Civilizations, does not replace the need for each and every one of the partial perspectives such as those discussed below:

Temporal biases

The temporal biases range from the classic periodizations Prehistory, Ancient Age, Middle Ages, Modern Age or Contemporary Age, to the histories by centuries, reigns, etc. Classical periodization (see its justification in «Division of historical time») is debatable both because of the need for transition periods and overlaps, and because it does not represent coincident periods for all the countries of the world (for which it has been accused of being Eurocentric)..

The annals were one of the origins of fixing the memory of historical events in many cultures (see in his article and below in Historiography of Rome). The chronicles (which already in their name indicate the intention of the temporal bias) are used as a reflection of the notable events of a period, usually a reign (see in his article and below in Historiography of the Middle Ages and Medieval and modern Spanish Historiography). The archontology would be the limitation of the historical record to the list of names that occupied certain positions of importance ordered chronologically. In fact, the same chronology, an auxiliary discipline of history, was born in many civilizations associated with the computation of past time that is fixed in the memory written by the names of the magistrates, as was the case in Rome, where it was more common to cite a year per year. be that of the consuls such and such. In Ancient Egypt, the dating of time was done by years (Palermo Stone), years, months and days of the pharaoh's reign (Royal Canon of Turin), or dynasties (Manetho). It is very significant that in non-historical cultures, which do not fix the memory of their past through writing, it is very common not to consider the specific duration of past time beyond a few years, which can be even less than the duration of a human life. Anything that happens outside of it would be "a long time ago", or in "time of the ancestors", which happens to be a mythical, ahistorical time.

The chronological treatment is the most used by most historians, since it is the one that corresponds to the conventional narration, and the one that allows linking the past causes with the effects in the present or future. However, it is used in different ways: for example, the historian always has to opt for a synchronic or diachronic treatment of his study of the facts, although many times they successively do one and the other.

- Treatment diachronic studies the temporal evolution of a fact, for example: I would study the formation of the working class in England over the centuries. XVIII and XIX)

- Treatment synchronous is fixed on the differences that the historical fact studied has at the same time but on different planes, for example: it would compare the situation of the working class in France and England at the juncture of the revolution of 1848 (both examples are taken from E. P. Thompson)

Periods or moments that are especially attractive to historians end up becoming, due to the intensity of the debate and the volume of production, true specialties, such as the history of the Spanish Civil War, the history of the French Revolution, the Soviet Revolution or the american.

The different conceptions of historical time are also worth considering, which according to Fernand Braudel range from long duration to punctual event, passing through conjuncture.

Methodological biases: unwritten sources

| Prehistory | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stone Age | Age of Metals | |||||||

| Paleolithic | Mesoly | Neolithic | Age of Copper | Age of Bronze | Age of Iron | |||

| P. Inferior | P. Media | P. Senior | Epipa-leolithic | Proto-neolithic | ||||

In the case of the prehistoric period, the radical difference in sources and methods (as well as the bureaucratic division of university chairs) make it a very distant science from what historians do, especially when such sources and methods are prolong, giving primacy to the use of archaeological sources and the study of material culture in periods for which there are already written sources, speaking then not of Prehistory, but rather of archeology with its own periodizations classical archaeology, medieval archaeology, even industrial archaeology. Less difference can be found with the use of oral sources in what is known as oral history. However, we must remember what has already been said (see above temporal biases) about the primacy of written sources and what these determine historiographical science and the consciousness of history itself in its protagonist —which is all humanity.

Spatial biases

Such as continental history, national history, regional history, or local history. The role of national history in the definition of the nations themselves is undeniable (for Spain, for example, from the medieval Chronicles to the history of Father Mariana (see nationalism, Spanish nation). It can also be seen, in this same article (history of history), how historians are grouped separately by nationality, as well as by era or trend.

Geography has concepts that are not more powerful but less arbitrary, which have allowed the construction of the prestigious branch of regional geography. Local history is undoubtedly the one with the easiest justification and universal validity, as long as it exceeds the level of simple scholarship (which at least will always serve as a primary source for works of greater explanatory ambition).

Thematic biases

They are the ones that would give way to a sectoral history, present in historiography since ancient times, as is the case with

- political history, reduced to evenemencial history or categorized in the history of institutions, the history of political systems, the history of law or military history;

- economic history, sometimes besieged with social history, which, however, can also be understood as a history of the workers' movement or a more universal history of social movements;

- the history of the Church, as old as herself, or the history of religions, born by the need to make her study comparative;

- the history of art, with precedents in classical Antiquity with the valuation of its artistic production and that of its past, but properly established in the Renaissance and above all with Neoclasicism;

- more recent than these, but encompassing them in a certain way, the history of ideas, which can include beliefs, ideologies or the history of science and technique and with them subdividing to infinity: the history of economic doctrines, the history of political doctrines...

One way of asking what the object of history is is to choose what deserves to be preserved in memory, which are the memorable events. Are they all, or are they only those that each historian considers transcendental? In the previous list we have the answers that each one can give.

Some of these denominations contain not a simple division, but opposing or divergent methodological visions, which have multiplied in the last half century. History is today more plural than ever before, divided into a multitude of specialties, so fragmented that many of its branches do not communicate with each other, without seeing a common subject or object:

- the microhistory, which is interested in the specificity of social phenomena from a perspective that has been compared to the magnifying magnifying magnification;

- the history of everyday life, which from a similar selection of the object, then opens the field of vision seeking generalization;

- history from below, centered on disadvantaged social groups, invisited in most of the usual historical records;

- the history of women or so-called gender studies, such as many cross-sectional stories, which can sometimes be encompassed as minority history, or thematically spread as the history of sensitivity, the history of sexuality, etc.;

- changes in economic history such as the lyliometry or history of the company;

- cultural history, which has a new impetus after several decades;

- the history of the present time, created in the 1980s and interested in the great ruptures of our time;

- climatology and genetics together with other disciplines, are being noticed more recently in the historiographic debate, through environmental or eco-history history, the increasingly used population genetic studies;

- the natural history to refer not only to geology and paleontology but also to many other Natural Sciences—the borders between the field to which this term refers and that of prehistory and archaeology are imprecise, through paleoanthropology—as well as Cosmology, and which is intended to be updated with the so-called Great History.

Auxiliary or related sciences of history

The fragmentation of the historical object can lead, on some occasions, to a very forced limitation of the historiographical perspective. Taken to an extreme, history can be reduced to the auxiliary science that is used to find an explanation for the events of the past, such as the economy, demography, sociology, anthropology, ecology, geography, etc.

On other occasions, the limitation of the field of study actually produces a historiographic genre:

Historiographical genres

It can be pointed out that there are historiographical genres that participate in history but can distance themselves more or less from it: one extreme would be occupied by the fields of fiction occupied by the historical novel, whose unequal value does not diminish its importance. Another extreme would be occupied by biography and an adjoining, systematic and extraordinarily useful genre for general history such as prosopography. Linked to history from the beginning of the written record, one of the main concerns in fixing the data was what we now call archontology (lists of kings and rulers).

Historiographic currents: the subject of history

In a more declared way, the historiographical currents tend to make their methodology explicit in a combative way, such as providentialism of Christian origin (we must not forget that in addition to the Greek historiographical tradition of Herodotus or Thucydides, the origin of Western historiography is strongly linked to sacred history), or Historical Materialism of Marxist origin (which triumphed in European and American intellectual and university environments in the mid-20th century AD, remaining dormant at least since the fall of the Berlin Wall).

Sometimes the labeling of currents is the work of their detractors, with which the historians classified in them may or may not be satisfied with the way in which they are defined. Such a thing could be said of providentialism itself, but it would be more appropriate for more modern currents, such as positivism, the eventual history (of events), etc.

Interpreting historiography as part of the intellectual environment of the time in which it arises is always necessary. All cultural production is dependent on the existing cultural model, call this fashion, style or the dominant paradigm in art or philosophy; and it is evident that the record of history is a cultural production. Deconstruction, weak thinking or postmodernity, concepts from the end of the XX century d. C., have been the incubator of the present deconstruction of history, which for some is only a narrative. A good way to distinguish the interpretation of history that a historiographical current has is to ask what it considers to be the historical subject or the true protagonist of history.

Historian groups

Groups of historians who share a methodology (and self-promote together with the powerful publication-citation mechanism) sometimes arise around journals, such as the French School of Annales (see in this article), the English Past and Present or the Italian Quaderni Storici; research groups or the university chairs themselves, which are the apex of the reproduction of the historiographical elites, through patronage and peer review.

Historiography as a science

History of history

The appearance of history is equivalent to that of writing, but the awareness of studying the past or leaving a record of memory for the future is a more complex elaboration than Sumerian temple annotations. The commemorative stelae and reliefs of battles in Mesopotamia and Egypt are already somewhat more approximate.

The rest of the Asian civilizations achieve writing and history at their own pace, compiling their theological sources in the form of holy books - sometimes with historical parts (the Hebrew Bible) or chronological sophistications (the Hindu Vedas) - record his own Annals and finally his own historiography, particularly the Chinese one, which has its Herodotus in Sima Qian (Historical Memoirs, 109 BC–91 BC) and reached a classic definition of standardized and official history, with the Ban Gu's Book of the Han (1st century AD), which set a pattern successively repeated by historians of subsequent periods in twenty-five "typified stories", up to 1928, in which the last of such a monumental series appeared.

In pre-Columbian America, outside of the Mayan civilization there are no texts in any way comparable. Both in this case and in sub-Saharan Africa, oral sources have traditionally been a priority. Attempts to construct an African historiography. Even so, there are some exceptional cases, such as the Timbuktu manuscript libraries, connected with North African travelers and conquerors, some of Andalusian origin such as León el Africano, well-known author of History and description of Africa and the extraordinary things it contains (1526).

However, the development and variety that historiography has reached in Western Civilization is of a different level from all of them.

Ancient Greece

The first Greek chroniclers, who were mainly interested in origin myths (the logographers), already practiced the recitation of events. His narration could be supported by writings, as was the case of Hecataeus of Miletus (second half of the VI century AD.. C.). In the V century d. C.a. C., Herodotus of Halicarnaso differs from them by his will to distinguish the true from the false; that is why he carries out his & # 34; investigation & # 34; (etymologically: "history"). A generation later, with Thucydides, this concern transformed into a critical spirit, based on the comparison of various oral and written sources. His History of the Peloponnesian War can be seen as the first true historiographical work.

The followers of the new literary genre of Herodotus and Thucydides were very numerous in Ancient Greece and include Xenophon (author of the Anabasis), Posidonius, Ctesias, Apollodorus of Artemis, Apollodorus of Athens, Aristobulus of Cassandrea (see Greek literature and Hellenistic historiography)

In the II century B.C. C., Polybius, in his Pragmateia (also translated as "History"), perhaps trying to write a work on geography, addresses the question of the succession of political regimes to explain how your world has entered the roman orbit. He is the first to search for intrinsic causes in the development of history rather than evoking external principles. At those heights of the Hellenistic period, the Library and the Museum of Alexandria represented the height of the Greek desire to preserve the memory of the past, which implies its appreciation as a useful tool for the present and the future.

Ancient Rome

Roman civilization has, like Homer and Hesiod the Greeks, origin myths collected by Virgil and poeticized in the Aeneid as an element of the ideological program designed by Augustus. Also, at least since the Republic, he maintained special care for the compilation of facts in Annals, written legislation and archives linked to the sacredness of temples. Until the Punic wars, the compilation of the main events that occurred was in charge of the pontiffs, in the form of annual chronicles.

The first complete Latin historical work is The Origins of Cato (III century AD. C. a. C.).

Rome's contact with the Mediterranean world, first Carthage, and above all Greece, Egypt and the Orient, was essential to broaden the vision and usefulness of its historical genre. Historians (whether Roman or Greek) will accompany armies on military campaigns, with the stated purpose of preserving their memory for posterity, collecting useful information, and justifying their actions. The cultured language, Greek, will be used for this genre along with the more sober Latin.

Sallustius, the Roman Thucydides, writes De Coniuratione Catilinae (the Conjuration of Catiline, of which he is a contemporary, 63 BC). He makes an extensive account of the distant causes of the conspiracy, as well as the ambitions of Catilina, portrayed as a degenerate and unscrupulous nobleman. In Bellum Ingurthinum (King Jugurtha's War of the Numidians, 111 BC to 105 BC), he denounces a colonial scandal. Historiae was his most ambitious and mature work, partially preserved, covering in five books the twelve years since Sulla's death in 78 BC. C. until 67 a. C. It is not the historical precision that interests him, but the narration of some events with their causes and consequences, as well as the possibility of clarifying the development of the process of degeneration in which the Republic was immersed. Apart from the individual, the object of his observation focuses on social classes and political factions: he idealizes a virtuous past, and detects a process of decadence that he attributes to moral vices, social discord and the abuse of power by the different political factions.

Julius Caesar with his Commentarii Rerum Gestarum, about two of the greatest wars he carried out: the Gallic War (58 BC-52 BC) (De Bello Gallico) and the civil war (49 BC-48 BC) (De Bello Civili).

Tito Livio (59 BC-AD 17), with the 142 books of Ab Urbe Condita, divided into groups of ten books known as &# 34;decades", most of which have been lost, writes a great national history, whose only subject is Rome ("fortuna populi romani") and whose only actors are the Senate and the people of Rome ("senatus populusque romanus" or SPQR). The general purpose of it is ethical and didactic; His methods were those of the Greek Isocrates of the IV d. C.a. C.: It is the duty of history to tell the truth and be impartial, but the truth must be presented in an elaborate and literary form. He uses the first analysts and Polybius as a source, but his patriotism leads him to distort reality to the detriment of the exterior and to have little critical spirit. He is a cabinet historian, he does not travel or personally know the scenes of the events that he describes.

Publius Cornelius Tacitus (55-120 AD), the great historian of the Empire under the Flavians, is above all an investigator of causes.

The list of historians from the Roman period is very extensive, both in Latin (Pliny the Elder, Suetonius...) and in Greek (Strabo, Plutarch).

During the decline of Rome, Christianity came to give a radical methodological change, introducing the providentialism of Augustine of Hippo. An example is Orosio, a Hispanic priest from Braga (Historiae adversum paganus).

Middle Ages

Medieval historiography is written mainly by hagiographers, chroniclers, members of the episcopal clergy close to power, or by monks. Genealogies, dry annals, chronological lists of events that occurred in the kingdoms of their sovereigns (royal annals) or succession of abbots (monastic annals) are written; lives (biographies of an edifying nature, such as those of the Merovingian saints, or later of the kings of France), and stories that tell of the birth of a Christian nation, exalt a dynasty or, on the contrary, they lash out at the wicked from a religious perspective. This story, which is shown by Moses of Corene (History of Armenia, V century d. C.), Isidore of Seville (Etymologies and Historia Gothorum, VII century AD), Venerable Bede (Ecclesiastical History of the English People, 8th century AD), Paul the Deacon (Historia gentis Langobadorum, 8th century AD), Eginhardo (Vita Karoli Magni, IX century AD) or Nestor the Chronicler (First Russian Chronicle, XI to XII); it is providentialist, of Augustinian inspiration, and inscribes the actions of men in the designs of God. We must wait for the XIV century d. C. so that chroniclers such as the French Froissart or the Florentine Matteo Villani are interested in the town, largely absent from the production of this period.

The Egyptian Ibn Abd al-Hakam wrote Futuh Misr wa'l-Maghrib ("Conquests of Egypt and the Maghreb"), where he compiles the sources of the VII to IX. Other medieval Arab historians included Al-Jahiz, Al-Hadani, and Al-Masudi (whom he compared to Herodotus). From an emigrant Andalusian family, the Tunisian Ibn Khaldún (end of the XIV century AD, beginning of the XV) has been highly valued by as a precedent for the philosophy of history and its innovative approaches in the fields of economics and sociology of its Al-Muqaddimah ("Prolegomena" or "Introduction" to his work, posed as a universal history).

For Spanish historiography, both Christian and Muslim, see his section.

Modern Age

During the Renaissance, humanism brought a renewed taste for the study of ancient, Greek or Latin texts, but also for the study of new supports: inscriptions (epigraphy), coins (numismatics) or letters, diplomas and other documents (diplomatic). These new auxiliary sciences of modern times contribute to enriching the methods of historians: in 1681 Dom Mabillon indicated the criteria that make it possible to determine the authenticity of a document by comparing different sources in De Re Diplomática. In Naples, more than two hundred years before, Lorenzo Valla at the service of Alfonso V of Aragon had managed to demonstrate the falsehood of the pseudo-Donation of Constantine. Giorgio Vasari with his Lives of Artists offers us both a source and a historiographical method for the history of Art.

At this time, history was no different from geography or even from the natural sciences. It was divided into two parts: general history (what we would call history today) and natural history (natural sciences and geography). This broad sense of history is explained by the etymology of the term (see History#Etymology).

The question of the unity of the kingdom raised by the religious wars of France in the XVI century d. C. give rise to works by historians who belong to the current called perfect history, which shows that the political and religious unity of modern France is necessary, as it derives from its Gallic origins (Etienne Pasquier, Recherches de la France). The providentialism of authors such as Bossuet (Discourse on Universal History, 1681), tends to devalue the significance of any historical change.

In parallel, history is shown as an instrument of power: it is placed at the service of princes, from Machiavelli and Guicciardini to Louis XIV's panegyrists, including Jean Racine.

Medieval and modern Spanish historiography

This was nothing new, and Spanish historiography is perhaps the most complete example of a secular effort to maintain the continuity of the written memory of the past, which gave such good service since the medieval Chronicles that justified the Reconquest, to consolidate the power of kings in the different Christian kingdoms.

The Chronicles

For Asturias, León and Castilla are linked successively in a very complete set, which really begins with two chronicles written in Andalusian territory:

- the Byzantine-Arabic Chronicle (741) and Chronicle Mozárabe (754), which precede a lost chronicle of the reign of Alfonso II and establish its continuity with those of Alfonso III at the end of the centuryIXd. C. (Albeldense Chronicle, Prophetic Chronicle, Chronic Rotense and Chronicle Sebastianense);

- the one of Sampiro (of the reign of Bermudo II, near 1000);

- of the centuryXIId. C. (Silence Chronicle around 1110, that of Pelayo, bishop of Oviedo, the Emperor Alfonso VII Chronicle and that of the anonymous monk of Nájera, these three at the end of the century;

- those of the reign of Fernando III the Holy (Chronicon mundi of Luke, bishop of Tuy, Latin Chronicle of the Kings of Castile of John, bishop of Osma and De rebus Hispaniae of the Archbishop of Toledo Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada;

- those of Alfonso X el Sabio (Estoria de España, edited by Ramón Menéndez Pidal with the title First General Chronicleand the Great and General Estoria);

- arriving at the centuryXIVd. C., highlighting the Chronicles of Pedro López de AyalaChronicle of King Don Pedro, that of Henry II, that of John I and the unfinished of Henry III), more sober and glued to the facts than the contemporary Europeans, although his primordial purpose was the self-justification of his author, Chancellor of Castile, who also composed a Rimado de Palacio where he describes his contemporaries.

In the 15th century d. C. the chronicle collection multiplied:

- Amount of Spanish Chroniclesby Pablo García de Santa María (up to 1412);

- Chronicle of John II (on facts from 1406 to 1434) by Álvar García de Santa María (h.1370-1460), Paul's brother; it is resumed with the name of Halconero Chronicle by Pedro Carrillo de Huete, being consolidated by Lope de Barrientos;

- Alfonso Martínez de Toledo (Arcipreste de Talavera) wrote in 1443 a Watchtower of the Chronicles;

- the Alvaro de Luna Chronicle (1453) is attributed to Gonzalo Chacón;

- Diego de Valera writes Abbreviated Chronicle of Spain or Valerian Chronicle (1482), which concludes in the reign of John II, the Memorial of various feats for Henry IV (1486-1487) and Chronicle of the Catholic Kings (up to 1488).

In the other peninsular Christian kingdoms, the chronicle literature is somewhat later, but produces the first general history of Spain in a Romance language: the Liber regum, written between 1194 and 1211 in Aragonese, which tells the story of the different Christian kingdoms from the mythical origins of peninsular history. In 851 the County of Aragon produced the Passio beatissimarum birginum Nunilonis atque Alodie. And from the later kingdom we have the Annals of San Juan de la Peña, from the 12th century d. C., which were copied in the Chronicle of the same name. A Brief Ribagorzana history of the kings of Aragon dates from the same century. the Historia de rebus Hispaniae.

For the Crown of Aragon, after the Gesta veterum Comitum Barcinonensium et Regum Aragonensium (starting in the century) XII AD and continued until the XIV), the Llibre dels feits or Chronicle of Jaime I the Conqueror; the Chronicle of San Juan de la Peña or Pedro the Ceremonious; that of Ramón Muntaner, which covers the period 1207-1328, including the famous expedition of the Almogávares, in which he participated; and that of Bernat Desclot Llibre del rei En Pere d'Aragó e dels seus antecessors passats (second half of the century XIII AD).

Completing the panorama of the peninsula is the Chronicle of the Kings of Navarre (1454) of the Prince of Viana (composed to justify his aspiration to the throne) and the Annales Portugaleses Veteres (987-1079).

16th century

After the unification of the Catholic Monarchs, already in the Modern Age, the monumental Historia de España by Father Mariana (De Rebus Hispaniae libri XX) explicitly continues with the same function. i>, 1592, increased to thirty books in his own Spanish translation in 1601), famous on the other hand for his defense of tyrannicide in De Rege et regis institutione written for the education of Felipe III. Other chroniclers of the 16th century d. C. are Florián de Ocampo and Ambrosio de Morales (continuing the General Chronicle in five books started by him); Jerónimo Zurita (Annals of the Crown of Aragon) and Esteban de Garibay (History compendium of the chronicles and universal history of all the kingdoms of Spain).

17th century

Baroque historiography includes fanciful historical manipulations, such as the lead figures from Sacromonte or the false chronicles of Ramón de la Higuera and Antonio Lupián Zapata. Fray Prudencio de Sandoval continued the chronicle of Ocampo and Morales and wrote a History of the life and events of Emperor Carlos V; Pedro de Salazar y Mendoza an Origin of the Secular Dignities of Castilla y León, and Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola the Anales de Aragón.

At the end of the XVII century d. C., the reflection on historiography itself arises in Spain as a necessity derived from the accumulation of such a huge chronicle corpus, its first attempt being the News and judgment of the most important historians of Spain, by Gaspar Ibáñez. de Segovia, Marqués de Mondéjar (published after his death in 1708).

Other historiographical genres

Other historiographical genres have also been cultivated since the Middle Ages, such as the treatment of an isolated figure (the Cid cycle), and already in the XV d. C. the memoirs (Leonor López de Córdoba, circa 1400), the biography (El Victorial by Gutierre Díez de Games, Generaciones y Semblanzas by Fernán Pérez de Guzmán) and the account of a specific event, such as the Book of the Honorable Passage of Suero de Quiñones, by Rodríguez de Lena. Travel books such as Pedro Tafur's or Ruy González de Clavijo's (who was ambassador to Tamerlán) provide very valuable information.

Al-Andalus

Muhammad al-Razi performs (in the first half of the X century AD, IV of the Hegira) the first general history of the Iberian Peninsula, Ajbar Mutuk al-andalus which was continued by other al-Razi: his son Ahmad (called in Spanish the Moor Rasis) and his son (Isa ben Ahmad). This story was spread in the Christian kingdoms under the name Crónica del moro Rasis and was used by Jiménez de Rada.

Aríb de Córdoba, secretary of al-Hakam II, wrote a Chronicle of his government, and in the same reign Muhammad al-Jusaní (died 361/971) the Kitáb al-qudá bi-Qurtuba, history of the cadíes (judges) of Córdoba.

In Almanzor's time, a very controlled history was written, such as that of Ibn Asim, significantly titled al-Ma'atir al-camiriyya (Amiri deeds), a work that we only know by reference.

Among historians of the 11th century d. C. (V of the Hegira), the golden age coinciding with the decomposition of the caliphate and the taifa kingdoms, the Cordovan Ibn Hazm (Fisal or Critical history of religions, sects) stand out and schools) and Ibn Hayyan (Muqtabis the Matin).

In the 13th century d. C., the alcireño Ibn Amira wrote the Kitab Raih Mayurqa (Book of the Kingdom of Mallorca).

Already outside the period of Muslim presence in Al-Andalus, Al-Maqqari completes the classical Islamic historiography, with his Nafh al-Tib (centuries XVI-XVII), which brings together many older fonts. Muslim sources are generally less well known, and would include post-Reconquista sources such as the little-known Historia of Ibn Idhari (XVI AD).

The Chroniclers of the Indies

The first works on the history of America, from the relationships of Christopher Columbus himself, his son Hernando and many other discoverers and conquerors such as Hernán Cortés or Bernal Díaz del Castillo (True History of the Conquest of New Spain), have a clear justifying character. The contribution to the contrary by Bartolomé de las Casas (A brief account of the destruction of the Indies) was so transcendental that it gave rise to the controversy of the just titles, in which Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda replied.; and even to the so-called Black Legend when it spread throughout Europe as anti-Spanish propaganda. The vision of the indigenous people, who saw their documents and material culture looted and destroyed, was made possible by some exceptional cases, such as the Inca Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala.

Officially, the position of Chronicler of the Indies began with the documentation gathered by Pedro Mártir de Anglería, which was passed on in 1526 to Fray Antonio de Guevara, Chronicler of Castile; and with Juan Gómez de Velasco who does the same with the papers of the major cosmographer Alonso de Santa Cruz, to which he adds the position of chronicler. Antonio de Herrera is appointed Senior Chronicler of the Indies in 1596, and between 1601 and 1615 he publishes the General History of the Castilian Facts on the Islands and Mainland of the Ocean Sea, known as Decades . Antonio de León Pinelo (raised in Lima, who had compiled the Laws of the Indies), Antonio de Solís and Pedro Fernández del Pulgar filled the position during the 20th century XVII d. C.. In the 18th century d. C. the institution is refounded with the creation of two others, very important for the maintenance of memory and Spanish historiography: the Royal Academy of History and the General Archive of the Indies. He still had time to highlight the figure of Juan Bautista Muñoz ( History of the New World , which he did not complete).

Illustration

In the 18th century d. C., a fundamental change took place: the intellectual approaches of the Enlightenment on the one hand, and on the other the discovery of alterity in other cultures outside of Europe (exoticism, the myth of the noble savage), aroused a new critical spirit. (although in fact, they are similar circumstances to those that could be seen in Herodotus). Cultural prejudices and classical universalism are questioned.

The discovery of Pompeii renews interest in classical antiquity (Neoclassicism) and provides materials that inaugurate a nascent science of archaeology. European nations far from the Mediterranean look for their historical origins in myths and legends that are sometimes invented (James Macpherson's Ossian, who pretended to have found Celtic Homer).

French Fenelon, Voltaire (History of the Russian Empire under Peter the Great and The Century of Louis XIV, 1751) and Montesquieu are also interested in national customs., who theorizes about it in The spirit of the laws. In England, Edward Gibbon writes his monumental History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776-1788), where he makes precision an essential aspect of the historian's job.

The limits of the historiography of the XVIIIth century d. C. are the submission to morality and the inclusion of party judgments, with which its object remains limited.

In Spain, the España Sagrada of the Augustinian father Enrique Flórez stands out, a collection of documents on ecclesiastical history, exposed with ultra-conservative criteria (1747 and continued after his death until the XX AD) and the Critical History of Spain of the exiled Jesuit Juan Francisco Masdeu; from a more enlightened perspective we would have the royalist Melchor Rafael de Macanaz, the critic Gregorio Mayans y Siscar (one of his disciples, Francisco Cerdá y Rico, tried to emulate Lorenzo Valla by discussing the veracity of the medieval vow of Santiago), and later in the century Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos himself, Juan Sempere y Guarinos, Eugenio Larruga y Boneta (Political and economic memoirs) , and the splendid compilation document that is the Journey to Spain by Antonio Ponz. Intermediate between both tendencies is the case of Juan Pablo Forner, casticista in his famous Apologetic Prayer for Spain and his literary merit (1786) and reformist in other works, published after his death..

19th century: history, erudite science

It is a period rich in changes, both in the way of conceiving history and in the way of writing it.

In France, it has been considered an intellectual discipline distinct from other literary genres since the turn of the century, when historians became professional and founded the French national archives (1808). In 1821 the Ecole nationale des Chartes was created, the first major institution for teaching history.

In Germany, this evolution had occurred before, and was present in the universities of the Modern Age. The institutionalization of the discipline gives rise to vast corpora that systematically gather and transcribe the sources. The best known is Monumenta Germaniae Historica, from 1819. The story gains a dimension of erudition, but also of actuality. It intends to compete with other sciences, especially with the great development that these are having. Theodor Mommsen contributes to giving scholarship a critical foundation, in his Römische Geschischte (History of Rome) 1845-1846, as well as collaborating on the aforementioned Monumenta Germaniae historica and Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum.

In France, since the 1860s, the historian Fustel de Coulanges writes history is not an art, it is a pure science, like physics or geology. However, history is involved in the debate of its time and is influenced by the great ideologies, such as the liberalism of Alexis de Tocqueville and François Guizot. Above all, he allows himself to be influenced by nationalism and even racism. Coulanges and Mommsen transfer the confrontation of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 to the historiographical debate. Each historian tends to find the qualities of his people (the & # 34; genius & # 34;). The great national histories are founded.

Romantic historians, such as Augustin Thierry and Jules Michelet, maintaining the quality of reflection and critical exploitation of the sources, are not afraid to expand on style and maintain it as an art. The methodological progress does not prevent contributing to the political ideas of his time. Michelet, in his History of the French Revolution (1847-1853), also contributed to the definition of the French nation against the Bonaparte dictatorship, as well as to anti-Prussian revenge (he died shortly after the battle of sedan). With the Third Republic, the teaching of history became an instrument of propaganda at the service of the education of citizens, and it will continue to be so throughout the century XX d. C..

Another of the founders of historiography in the XIX century d. C. was Leopold Von Ranke, who was very critical of the sources used in history. He was against analysis and rationalization. His adage was to write history as it was. He wanted eyewitness accounts, emphasizing his point of view. Important German historians of the 19th century d. C., who did not participate in his claim to objectivity, were Johann Gustav Droysen (he established the concept of Hellenism ) and Heinrich von Treitschke (of important political activity, who coined the anti-Semitic motto The Jews are our misfortune!). Hans Delbrück developed military history.

The epistemological role of the science of history is subject to the great intellectual schemes that are built from philosophical currents such as positivism and historicism. Historicism is dominant among Ranke's followers in Germany, with a marked idealistic component: ideas are the roots of the historical process when embodied in men or institutions. Positivism is dominant in France (Coulanges, Hippolyte Taine), where historiography is more analytical than narrative, avoiding transcendental explanations and seeking the ultimate explanation of the facts in the very nature of things. In England there was an eclectic and moderate synthesis of positivism and historicism (Lord Acton, John B. Bury, both Cambridge dons).

Wilhelm Dilthey's proposal for the separation of fields between the objective natural sciences; and the spiritual sciences, subjective, placed history among them. His desire was to overcome both erudition understood as mere collection of individual facts, as well as the use of methods from sciences alien to history, for which he opted for psychological laws to guarantee the scientific nature of the interpretation of events.

Hegel and Marx introduce social change into history. Previous historians had focused on the boom and bust cycles of rulers and nations. A new emerging discipline brings analysis and comparison on a large scale: sociology. From the history of art, studies such as Jacob Burckhardt's on the Renaissance become the reference for understanding cultural phenomena. Archeology puts myth in contact with historical reality, both in Egypt and in Mesopotamia and Greece (Heinrich Schliemann in Troy, Mycenae and Tiryns, and later Arthur Evans in Crete); all this in a romantic and adventurous atmosphere that is refined to become scientific, although it does not disappear, as evidenced by the late contribution of Howard Carter (Tutankhamun) and the popular image of archaeologists that perpetuates the cinema (Indiana Jones). Anthropology applied to the explanation of myths produced the monumental work of James George Frazer (The Golden Bough), from which historians were able to reconsider their point of view on the relationship of human societies between all ages with magic, religion and even science.

During the 19th century d. C., Spain maintains at least its documentary heritage with the creation of the National Library and the National Historical Archive, but it is not distinguished by a great renewal of its historiography that, apart from the Arabism of Pascual de Gayangos or the economic history of Manuel Colmeiro, appears split between a liberal current (Modesto Lafuente y Zamalloa, Juan Valera), and another traditionalist one, whose top, the scholar and polygraph Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo (History of the Spanish heterodox) , is a worthy continuation of the tradition that began with Saint Isidoro and passed through the History of Father Mariana and the Sacred Spain of Father Flórez.

20th century

History is establishing itself as a social science, a scientific discipline involved in society. At the beginning of the XX century d. C., history had acquired an undeniable scientific dimension, a leading role in education and a solid institutional structure. To the Academies, university departments and specialized magazines, professional associations were added, such as the American Historical Association, founded in 1884.

History, between positivism and essayism

Installed in the world of teaching, erudite, the discipline is influenced by an impoverished version of Auguste Comte's positivism. Claiming objectivity, history limits its object: the isolated fact or event, at the center of the historian's work, is considered the only reference that correctly responds to the imperative of objectivity. Nor does it deal with establishing causal relationships, substituting rhetoric for the discourse that was claimed to be scientific.

Simultaneously and in contrast, related disciplines tend to generalize, such as cultural history or the history of ideas, with Johan Huizinga (The Autumn of the Middle Ages) or Paul Hazard (The crisis of European consciousness) among its initiators. Essayists such as Oswald Spengler (The Decline of the West) and Arnold J. Toynbee (A Study in History) in famous controversy, publish profound reflections on the very concept of civilization that Along with the Rebellion of the Masses or Invertebrate Spain by José Ortega y Gasset, they were extraordinarily popular, as they reflected the intellectual pessimism between the wars. Closer to the historian's method, and no less profound, is the work of his contemporaries, the Belgian Henri Pirenne (Mohammed and Charlemagne) , or the Australian Vere Gordon Childe (father of the Neolithic Revolution concept)..

However, the main transformation of the history of events comes from foreign contributions: On the one hand, Marxist-inspired historical materialism, which introduces the economy into the historian's concerns. On the other hand, the disturbance caused in historiography by the political, technical, economic or social developments that the world knows, without forgetting world conflicts. New auxiliary sciences appear or develop considerably: archaeology, demography, sociology and anthropology, under the influence of structuralism.

The Annales School

Around the journal Annales d'histoire économique et sociale, founded by Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch in 1928, a current of thought arose (the so-called Annales school) that enlarged the field of the discipline by requesting the confluence of other sciences, particularly sociology; and more generically, it transformed history by expanding its object beyond the event and inscribing it in the long duration (longue durée). After the hiatus of the Second World War, Fernand Braudel continued the magazine and for the first time resorted to geography, political economy and sociology to prepare his thesis on world-economy (a classic example is The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean world in the time of Felipe II).

The role of historical testimony changes: it remains at the center of the historian's concerns, but it is no longer the object, rather it is considered as a tool to construct history, a tool that can be obtained in any domain of knowledge. A constellation of authors more or less close to Annales participate in this methodological renewal that fills the middle decades of the XX century d. C. (Georges Lefebvre, Ernest Labrousse).

The vision of the Middle Ages changes completely after a critical rereading of the sources, which have their best part precisely in what they do not mention (Georges Duby).

Privileging the long duration over the short time of the history of events, many historians have proposed rethinking the field of history since Annales, among them Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie or Pierre Goubert.

Alternatives to Annales

Other French historians, outside Annales, Philippe Ariès, Jean Delumeau and Michel Foucault, the latter on the frontiers of philosophy, describe the history of subjects of daily life, such as death, fear and sexuality. They want history to write about every topic, and every question answered.

From a completely opposite orientation (the Catholic right), Roland Mousnier made a decisive contribution to the social history of the Old Regime, denying the existence of class struggle and even class struggle, for the benefit of what he describes as a society of orders and client relationships.

Third generation of Annales: "new history" or "new cultural history"

"New Story" It is the denomination, popularized by Pierre Nora and Jacques Le Goff (Making History, 1973), which designates the historiographical current that animates the third generation of Annales. The new history tries to establish a serial history of mentalities, that is, of the collective representations and mental structures of societies.

Also located within the third generation of the Annales school, the historiographical current called "new cultural history" It begins in 1966 and still persists today. Its clear reference is the new anthropological history, a branch of anthropology, whose greatest exponents of the subject were Bronislaw Malinowski and Clifford Geertz. Like the first two generations of Annales, this current handles interdisciplinarity with other social sciences; In addition to having anthropology, it also has the collaboration of sociologists, psychologists, linguists, etc.

Among its most significant representatives are Peter Burke, Roger Chartier, Robert Darnton, Patrice Higonnet, Lynn Hunt, Keith Jerkins and Sarah Maza. Its object of study focuses on cultures throughout history, meaning "cultures" according to the definition of Clifford Geertz in his method of "thick description", to the symbolic dimension of action as a set of inherited meanings and symbolically expressed in the habits of daily life. Cultural history considers that all past societies have had culture, without making value judgments in considering some better or worse than others. Another key principle of this historiographical current is to apply the concept of "otherness", that is, to see the "other" from "the other" to other cultures. They consider that there is no homogeneous culture, but that there are "subcultures" inserted in turn, within other cultures, civilizations or regions. Culture is conceived as the tradition received and modified by those who have inherited it, and who, in turn, have made a "symbolic construction" of the companies.

French historiography rethinks its Revolution

It has been said that each generation has the right to rewrite history. In the academic field, the revision of the ways of understanding the past is part of the task of the professional historian. The extent to which this revision is scientifically posed, as a distortion of previously established certainties (Karl Popper) and not pseudoscientifically, as would be done by what is pejoratively called historiographical revisionism, is difficult to assess. A touch test would be to detect if the revisionist is an outsider of the academic world, who is dedicated to the political use of history, which on the other hand is a common vice: history has always been used as a weapon in social transformation, and academic media have never been an exception. In historiography, social science, it is difficult to see if we are facing a paradigm shift like the ones studied by Thomas Kuhn for the experimental sciences (History of scientific revolutions) , fundamentally because there is never such a universal consensus shared enough to understand that the deviation from it is a revolution.

One of the great revisionist controversies (in a good way) came with the second centenary of the French Revolution (1989). Authors with a structuralist tendency, close to Annales (François Furet or Denis Richet), synthesized the studies of the 1970s and 1980s in what was intended to be a new interpretative paradigm alternative to the Marxist one that had dominated history period: Albert Soboul, Jacques Godechot, and more recently Claude Mazauric, Michel Vovelle or Crane Brinton (Anatomy of the Revolution). Far from both tendencies, Simon Schama and the new narrativists make a cultural history of the political and very narrative, anti-structuralist and tendentially conservative overtones (initiated by Richard Cobb already in the 1970s). He also keeps his distance from René Rémond's nouvelle Histoire Politique. Arno Mayer laments that the revision has given way to a political use of history in which revolutions are condemned a priori as inherently evil.

A subgenre: commemorations

On the other hand, the use of history to celebrate events that celebrate "round" (centennials, decades old, etc.) is an opportunity for historians to shine professionally, to bring the discipline closer to the general public and to provide an alibi for different types of justifications. The bicentennial of the United States (1976) had been a difficult precedent to overcome in terms of media impact and economic cost. The last ones that we remember for Spain were that of the Spanish Civil War (1976, with the innovative exhibition of the Palacio de Cristal in the Jardines del Retiro curated by Javier Tusell; 1986, the fiftieth anniversary that was also used to remember particularly Antonio Machado, and García Lorca with the left in power; 1996; 2006, with the debates on historical memory), Carlos III (1988, in emulation of the parallel preparation of the French bicentennial), the Fifth Centenary of the Encounter between two Worlds (1992), Cánovas (1998), the Year of Quixote (2005). There is even a State Society for Cultural Commemorations, which maintains a busy schedule.

Without the need to commemorate anything more concrete than its own timelessness, but with the same justifying desire (in which it has millennia of advantage) the Spanish Catholic Church has carried out the most remarkable set of exhibitions: The Ages of Man , thematic review of religious affairs successively illustrated with different historical-artistic supports exquisitely selected and exhibited (books, music, sculpture...) traveling through the cathedrals of Castilla y León, which in themselves already justified the visit. The same format and curator had Immaculate, which commemorated the 150th anniversary of the dogma (Cathedral de la Almudena, Madrid, 2006) and which served to compensate for the recent inauguration of the building, whose taste and decoration were discussed. Inspired by them, the Navarrese government organized the exhibition The Ages of a Kingdom (Pamplona 2006, coinciding with the centenary of San Francisco Javier in Javier).

Anglo-Saxon Historiography

The United States is prodigal in experimenting with new methodological approaches, such as

- the quantitativeity of lyliometry or new economic history (new economic history) American, by Robert Fogel and Douglass North, 1993 Nobel Prize in Economics (of the few historians who have received the Nobel Prize, with the literature of Theodor Mommsen and Winston Churchill).

- the case-studies (since the 1970s). A case study is a particular method of qualitative research. Rather than using large databases and rigid protocols to examine a limited number of variables, this method involves a longitudinal examination of a case: a single fact. History approaches the experimental method.

- The call World History (since the 1980s), which compares differences and similarities between regions of the world and comes to new concepts to describe them (consider Arnold J. Toynbee a precursor).

The role of the United States as a recipient of European intellectuals before and after the Second World War is also noteworthy, as was the case of Mircea Eliade, the greatest innovator of the history of religions or history of beliefs (The sacred and the profane, The myth of the Eternal Return).

But the main contributions of English historians, who have publications comparable to Annales (Past and Present) are at the center of the mainstream of historiographical production, in the case of this magazine, with a Marxist tendency, among which are authors of the stature of E. P. Thompson, Eric Hobsbawm, Perry Anderson, Maurice Dobb, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, Paul Sweezy, John Merrington... who in no way we must understand it as a unitary tendency, since, after the years of the Second World War and its post-war (in which many of them functioned as the Group of Historians of the Communist Party of Great Britain) they were moving away from each other and from orthodox Marxist positions, giving rise to what has come to be called the Marxian tendency. The polemics between them and with non-Marxist authors, such as H. R. Trevor-Roper, became deservedly famous.

Each author must be seen through his personal position, such as the Americans John Lukacs, Gertrude Himmelfarb, Peter Gay (psychological perspective) or Immanuel Wallerstein (from the field of economic and social history, who has developed a concept of world system along the lines of Fernand Braudel); the British Steven Runciman (essential medievalist for the Crusades), E. H. Carr or Lawrence Stone; Canadians Donald Creighton or Bruce Trigger (ethnohistorian and archaeologist); or the aforementioned Arno Mayer, Richard Cobb, Crane Brinton or Simon Schama.

Italian historiography

Around the magazine Quaderni Storici, a group of Italian historians developed from the end of the century XX d. C. an innovative extension of social history that they called Microhistory (Giovanni Levi, Carlo Ginzburg). With some approximation to this method, Carlo M. Cipolla mainly makes an economic history of great importance, as well as interesting methodological reflections (the parody Allegro ma non troppo).

German historiography

The introspection of German intellectuals before their role in the face of Nazism and the different degrees of responsibility of the nation, the people or the German ruling classes on the two world wars and the convulsive period between the wars that witnessed the rise of Nazism was object of the attention of historians of very different tendencies, such as Gerhard Ritter Hans-Ulrich Wehler or Karl Dietrich Bracher. The so-called historians' controversy of the eighties between the philosopher Jürgen Habermas (who maintained the constant presence of Nazism) and historians such as Ernst Nolte and Joachim Fest (who sought to distance themselves from " that past that does not pass" analyzing issues as thorny as the Holocaust from a perspective that seemed almost justifying to his opponents, equating Nazism and communism) presided over the eighties, prior to the German reunification of 1989.

The Hispanists

The availability of documentary raw material in Spanish archives attracts professionals trained in European or North American universities, in a kind of upside-down brain drain that renewed the methodology and perspectives of Spanish historians.

Maurice Legendre was one of the initiators of French Hispanism through the House of Velázquez, followed by an impressive roster: Marcel Bataillon (with his essential Erasmus in Spain), Pierre Vilar (Catalonia in Modern Spain and his brief but influential Historia de España), Bartolomé Bennassar (model of how local history can be integrated into the mainstream of avant-garde historiography with his Valladolid in the Golden Age),Georges Demerson, Joseph Pérez (authority for the Communities, the Inquisition, the Jews...), Jean Sarrailh (example of synthesis of a period with Illustrated Spain in the second half of the XVIII century AD)...

One of the deans of Anglo-Saxon Hispanicism is Gerald Brenan (observer of The Spanish Labyrinth from his vantage point in the Alpujarras), seconded by a list no less impressive than the French: Hugh Thomas (for a long time the most cited author in his specialty with Spanish Civil War), John Elliott (who with El Conde-Duque de Olivares has shown how a biography can reflect an era), John Lynch, Henry Kamen, Ian Gibson (Irish nationalized Spanish, author of essential biographies of the cultural giants of the XX century AD), Paul Preston, Gabriel Jackson, Stanley G. Payne, Raymond Carr, Geoffrey Parker, Edward Malefakis...

Contemporary Spanish historiography

Meanwhile, Spanish universities are emptying out due to the civil war and internal and external exile. In the middle of the XX century d. C. a large group of individuals could be seen spread all over the world: Ramón Menéndez Pidal, Américo Castro, Claudio Sánchez Albornoz, Julio Caro Baroja, José Antonio Maravall, Jaume Vicens Vives (to whom we owe, among other contributions, the creation of the Index Historical Spanish in 1952), Antonio Domínguez Ortiz, Luis García de Valdeavellano, Ramón Carande and Thovar...

In the postwar period, the CSIC was created, whose organization chart included history departments. The requisition of papers by the winning side for repressive purposes and their concentration will allow the operation of a section of the National Historical Archive in Salamanca specialized in the Spanish Civil War (since 1999 called the General Archive of the Spanish Civil War). It was the center of a controversy that transcended the field of the historiographical to fully enter the field of the political, very intense between 2004 and 2006, for the return to the Generalitat of Catalonia of the originators of this institution and other Catalans (the so-called Salamanca papers), which can be considered as part of the simultaneous controversy surrounding the so-called recovery of historical memory.

In the second half of the XX century d. C. there is an intense methodological renewal in all branches of historical science, and university departments multiply. Some historians return from exile, where they had remained as referents for a way of making history that was not subject to censorship. This is the case of Manuel Tuñón de Lara, concerned with methodological reflection (historical materialism) while maintaining a militant position in policy. It is worth noting the work carried out, also in France, by the Ruedo Ibérico publishing house, whose books were distributed semi-clandestinely, as well as some in Mexico (Fondo de Cultura Económica).

There is a clear division between a minority of conservative historians (Luis Suárez Fernández, Ricardo de la Cierva) and a majority open to new trends, who do not form a united historiographical current. See Gonzalo Anes, Julio Aróstegui, Miguel Artola, Ángel Bahamonde, Bartolomé Clavero, Manuel Espadas Burgos, Manuel Fernández Álvarez, Emiliano Fernández de Pinedo, Josep Fontana, Jordi Nadal, Gabriel Tortella, Javier Tusell, Julio Valdeón Baruque...

The prominent figures in specific fields of study are noteworthy: Francisco Tomás y Valiente and Alfonso García-Gallo in the history of Law, Emilio García Gómez in Arabism, Guillermo Céspedes del Castillo in Americanism, the Antonio García y Bellido and Antonio Blanco Freijeiro in archaeology, those of Pedro Bosch Gimpera, Luis Pericot, Juan Maluquer or Emiliano Aguirre in prehistory (that of the latter linked to the beginning of the exceptional site of Atapuerca, whose study is continued by Juan Luis Arsuaga, Eudald Carbonell and José María Bermúdez de Castro who have placed Spanish prehistory at the center of world attention).

Eccentric story. Faking history

You cannot fail to refer to what could be called the eccentric story, or one that is far from the "consensus" or central field of work for "official" historians. There has always been similar literature, and a notable example could be remembered, such as Ignacio Olagüe and his book The Islamic Revolution in the West, which sought to prove the non-existence of an Arab invasion in the VIII d. C., and which obtained some echo in the 1960s and 1970s.

Currently, the debate surrounding the Second Spanish Republic, the October Revolution of 1934 and the Spanish Civil War, which even affects issues as seemingly strange as what date to take as its beginning, is filling the shelves from supermarkets with a literature that some call historical revisionism, due to its parallelism with Holocaust denial. The need for certain historiographical affirmations or denials to be subject to criminal sanction is the subject of debate.

Spanish is not the only historiography that has to deal with eccentricity: the most striking case in recent years has surely been that of the attribution of the discovery of America to the Chinese admiral Zheng He.

To cross the border of eccentric history is to enter fully into historical fraud, in which there are egregious precedents: from the Donation of Constantine (which justified the temporal power of the popes) to the Protocols of the Wise Men of Zion (which fueled anti-Semitism and is at the origin of the Judeo-Masonic Conspiracy). The most bizarre recent case (without reaching the success of the previous ones, so that at most it can be compared to the failed attempts to falsify history, such as the Sacromonte bullets), is that of the famous (and false) Hitler Diaries. published by Stern magazine in 1983, with which a historian as serious as Trevor Roper was fooled or allowed himself to be fooled. The last to be revealed, for the moment, is that of the falsified documents introduced into British archives that supported the books where Martin Allen revealed strange conspiracies during World War II.

The use of historiography to falsify history is as old as the discipline itself (one would have to go back at least to Ramses II and the battle of Kadesh), but in the XX d. C. the capacity reached by the State and the mass media (called fourth power) allowed totalitarian regimes to play with the possibility of changing history, not only towards the future, but also towards the past. George Orwell's novel 1984 (1948) is testimony to how plausible this was. Retouched photographs were a specialty not only of Stalin against Trotsky, but of Francisco Franco himself with Hitler. Winston Churchill himself was clear, even from democracy, that "History will be kind to me, because I intend to write it". Reflecting on whether history is written by the victors is a task more typical of the philosophers of history.

The truth is that in history everything changes, nothing is permanent, and much less its concealment, as evidenced by the debate on the rising auction of malignancy between left and right, which will still lead to many books such as that of Stéphane Courtois (The Black Book of Communism, 1997) and its response The Black Book of Capitalism.

Contenido relacionado

Ernst Bloch

University of Vienna

Etymology of Peru