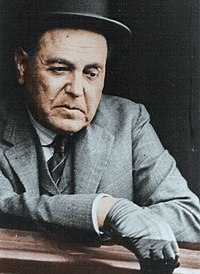

Hipólito Yrigoyen

Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen (Buenos Aires, July 12, 1852-ibidem, July 3, 1933), known as Hipólito Yrigoyen, was an Argentine politician and statesman, twice president of the Argentine Nation and a relevant figure within the Radical Civic Union. He was the first Argentine president elected by secret and compulsory male suffrage (the female vote was used for the first time in 1951) according to the Sáenz Peña Law of 1912.

His first term began in 1916, with which the period known as the first radical presidencies began, and he was elected again in 1928, without completing his term, interrupted by the coup d'état of 1930, the first of these anti-democratic movements in Argentina.

He was the nephew of Leandro N. Alem, founding leader of the Radical Civic Union, whom he admired but also strongly criticized. He was police commissioner for the Balvanera neighborhood and participated in the Revolution of 1874, led by Bartolomé Mitre. He worked as a teacher and Domingo Sarmiento named him president of the Balvanera School Council. He was elected provincial deputy on two occasions, for the period 1878 to 1880 and national deputy from 1880 to 1882, this last period interrupted by the federalization of Buenos Aires. He participated in the failed revolutions of 1890 and 1893, against the Roquista regime. He was one of the founders of the Civic Union in 1890 and the Radical Civic Union in 1893, under the leadership of Alem. Faced with electoral fraud, he maintained a policy of electoral abstention and in 1905 he led a third armed uprising that was defeated again. In 1910 he negotiated with President Roque Sáenz Peña the secret and compulsory male suffrage law, under whose rules he was elected President of the Nation in 1916.

His presidency put an end to a conservative hegemony of more than 40 years and meant access to political power for the socio-cultural sectors called the middle class. He was also the first to take a nationalist line. He enacted regulations to protect peasants and created retirement funds for public employees. He dictated measures for Argentina to control its transportation, energy deposits and its own currency. He regulated the rates of the railways operated by British capital, at the same time that state railway lines were created. In 1922 he founded Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF), a state company destined to exploit the country's oil wealth. The outbreak in 1918 of the student movement for University Reform was supported by his government, taking a series of measures in favor of the reformists. Despite the initiatives that favored working-class sectors and the media, his mandate was marred by the largest worker massacres in Argentine history: the Tragic Week, the La Forestal Massacre and the rebel Patagonia, with thousands of workers murdered by the forces of security to which he gave the order to repress and extreme right-wing parapolice groups whose leaders included members of the ruling party, against whom the government did not take measures to arrest them. In matters of international politics, Yrigoyen maintained a neutral position before the First World War and, after it, advocated equality between victorious and defeated nations, while defending the principle of non-intervention.

Yrigoyen was questioned by members of his own party for exercising a "personalist" leadership. He was succeeded in the presidency by Marcelo T. de Alvear, also a radical, during whose mandate the UCR split into two parties, one grouping the Yrigoyenists and the other the anti-personalists. The presidential election of 1928 was polarized between two radical parties: on the one hand, the Radical Civic Union with Yrigoyen at its head, and on the other, the Antipersonalist Radical Civic Union (a more conservative faction of the same) with the candidacy of Leopoldo Melo. Yrigoyen won for the second time with a large majority in an election that was known as "the plebiscite." During his second term, the Crack of 1929 occurred, the most serious global financial crisis up to that time. The government was unable to react to the crisis and was losing support. On September 6, 1930, he was overthrown by a coup led by General José Félix Uriburu. Shortly before his overthrow, his government came close to achieving the nationalization of oil, a fact that is considered one of the causes of the coup.

After the coup, he was stripped of his wealth as a rancher, and was confined to Martín García Island, where he shared a prison with various political prisoners. He died on July 3, 1933. His funeral was one of the most massive and surprising spontaneous demonstrations in Argentine history, directed to the pantheon of those who fell in the Parque Revolution, which is where it has remained since then. The political orientation of the Yrigoyen government gave rise to the appearance of "yrigoyenismo" as an ideological current within Argentine radicalism. Many Yrigoyenista leaders later joined the ranks of Peronism in the 1940s.

Biography

Childhood and youth

Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen was born, according to his baptismal certificate, on July 12, 1852, a few months after the battle of Caseros, although Félix Luna maintains that this date may be wrong and the day of birth would be July 13. He was baptized four years later, on October 19, 1856 in the church of Nuestra Señora de la Piedad. His father, Martín Yrigoyen Dodagaray, was a Basque-French immigrant who married Marcelina Alen Ponce in 1847, the daughter of his employer Leandro Antonio Alén (also father of Leandro N. Alem), a rosista mazorquero who would be shot and hanged in the Plaza de Mayo.

During his childhood, Yrigoyen lived in a house in the Balvanera neighborhood and had four siblings: Roque, Martín, Amalia and Marcelina. In 1861, at the age of nine, he entered the Colegio San José in Buenos Aires run by the Bayonnese parents, but continued his studies at the Colegio de la América del Sud, where his uncle Leandro N. Alem was a philosophy professor.. Yrigoyen was not an outstanding student among the others, although he did show an introspective personality. At first he had an inclination for priestly studies, but he left them soon after to pursue law. For some time Yrigoyen and Alem shared the same home, and the latter tried to introduce his nephew into Freemasonry.

At the age of fifteen, Yrigoyen interrupted his studies to help his father, who had acquired a fleet of cars to work in the port. He worked for a short time in a store and also had a job on the streetcar. At his young age he had already had extensive work experience, although always marked by dispersion.In 1867 he began working in the law firm shared by Leandro Alem and Aristóbulo del Valle.

According to research by Roberto Etchepareborda, his original last name —unlike that of Bernardo de Irigoyen— was Hirigoyen, which means "city on high." In the Basque-French country the "h" is aspirated as in English, while in the Basque-Spanish country it is not pronounced, therefore the surname Hirigoyen probably originates from France, while its variants Yrigoyen and Irigoyen do. in Spain. In 1965, after the investigation by Etchepareborda, the National Academy of History decided to name Yrigoyen, with the initial "y".

The radical leader used «Yrigoyen» and «Irigoyen» interchangeably. The use of "Yrigoyen" was a political use of the fourth decade of the XX century: Gabriel del Mazo, leader of FORJA, He recommended using the «Yrigoyen» as opposed to the «Irigoyen» used by the sectors that responded to Marcelo T. de Alvear.

Political career

When he finished high school in 1869, together with his uncle, Leandro N. Alem, they began their political life as members of the Autonomist Party, led by Adolfo Alsina, a grassroots party opposed to Bartolomé Mitre's National Party. Participation in the Electoral Club called for free suffrage, division of rural property, and reform of the judiciary, among other measures.

In 1870 he entered the public administration as a clerk for the General Accounting Office in the Balance Sheet and Information Office, but he did not stay in that job for long. Two years later, when Alem was elected provincial deputy, Yrigoyen, at the age of twenty, was appointed commissioner of Balvanera thanks to the influence of his uncle Leandro N. Alem, and took charge of section 14. At the same time, he continued with his studies in lawyer and in March 1874 he finished his fourth year, at the same time, he participated in the revolution that took place that same year, led by Bartolomé Mitre.

In 1877 Alem, Aristóbulo del Valle and Yrigoyen, in disagreement with Adolfo Alsina's approach to Mitrismo, formed the Republican Party, which proposed Aristobulo del Valle himself as its candidate and maintained an attitude of intransigent opposition to the agreements between leaders alsinistas and mitristas. The internal confrontation ended with the expulsion of Yrigoyen from his police functions in 1877. In 1878, at the age of 25, he was elected provincial deputy for the Republican Party and integrated the Budget Commission, but his term ended in 1880 as a result of the federalization of Buenos Aires. In that year he was appointed general administrator of Seals and Patents, but he did not stay in this job for long either. When Buenos Aires was federalized and faced with the arrival of Julio A. Roca to the presidency, Alem resigned from his seat as deputy in protest against the federalization and abandoned politics, while Yrigoyen, who did not oppose the new law, was elected national deputy. It was the first discrepancy that arose between the two.In 1878 he finished taking the subjects, but he never did his thesis. Three years later, a law was enacted that allowed obtaining a law degree without writing a thesis, so Yrigoyen processed and obtained his degree.

He began working as a professor of Argentine history, civic instruction and philosophy in 1880, at the Normal School of Teachers, but not before having been appointed president of the Balvanera School Council by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, then president of the National Council of Education. He taught these subjects for nearly twenty-four years, until he was expelled by order of President Manuel Quintana, a product of the 1905 revolution, led by Yrigoyen. He donated his salary of 150 pesos to the Children's Hospital and the Home for Destitute Children, despite the fact that their economic situation was not favourable. The testimonies of the time criticize his teaching method by which he placed the responsibility of the classes on his own students while he acted as an observer and moderator. Decades later this didactics would be known as: "centered teaching in the student". In 1882 Yrigoyen had completed the theoretical subjects of the Law degree at the University of Buenos Aires, remaining only to take the practical ones. At that time, and through the Spanish Krausists Julián Sanz del Río and Francisco Giner de los Ríos, he discovered the philosophical principles of Karl Krause, which greatly influenced his thinking.

During the 1880s, Yrigoyen dedicated himself to farming, from which he obtained significant income; he bought and leased fields in the provinces of Buenos Aires, Córdoba and San Luis, dedicating himself to fattening cattle for sale to meat packers. In total, his fields amounted to almost 25 leagues of land.Among other lands, he owned the El Trigo ranch, near Las Flores, Buenos Aires province, one of the best grazing areas in the country; la Seña in Anchorena, province of San Luis and El Quemado near General Alvear, province of Buenos Aires, in addition to leasing the fields of Santa María and Santa Isabel in the game of July 9, in Buenos Aires. Thanks to this experience Yrigoyen had direct contact with country people, Creoles or gringos, and learned about their problems and sensitivity. In a few years, Yrigoyen went from receiving a modest income to owning a considerable fortune, which he will allocate to his political projects.

He never received people or friends in his stays. She spent her time working in the fields with her laborers, and in free time he used to walk or read. When she was a more popular political personality, he used to seclude himself in one of his rooms as a way of rest. He advised his peons to buy small properties to support themselves in his old age. The workers of the Yrigoyen farms received higher salaries than usual at that time, and also received a share in the profits obtained, depending on the work and responsibility of each employee. It was common for him to give clothes and clothes to his laborers and, when he returned from his trips to the city, he also brought orders from his employees. Yrigoyen amassed a fortune of several million pesos, which he used almost entirely in political activity, through such an extent that, at the time of his death, his succession left a deficit.

The 1880s marked the consolidation of a landowning and commercial elite tied to a balance guaranteed by Julio Argentino Roca, first from the government and then from outside it. The agreement between different dominant sectors led to the exclusion of any organized opposition. In this framework, the opposition was united in a new party, after dissolving the Youth Civic Union, it was rearmed in the new Civic Union formed in 1890, emerged as a heterogeneous movement whose main ideology was suffragism and the fight against the regime. after the success of the meeting held in the Jardín Florida on September 1, 1889, a meeting that helped popularize Leandro N. Alem, who had retired from political life, among the youth of Buenos Aires since the 1880s, it also served as a kick-start to organize the Park Revolution.

Yrigoyen initially hesitated to join the movement, since he maintained that the fight was not against one person, President Miguel Juárez Celman, but against an entire system. But before the events of the 1990 Revolution, he hurried to join and was quickly appointed police chief of the provisional government, although the movement would be quickly put down by the government, and the pacts between the most conservative sectors of the Civic Union with the government ended up plunging the party into a deep internal crisis. Thus, the pacts with the conservatives would lead to the bankruptcy of the Civic Union, forming on June 26, 1891 two new parties: the National Civic Union headed by Bartolomé Mitre, a supporter of to negotiate with rockism, and on the other hand the Radical Civic Union headed by Alem, supporter of a radical opposition against rockism. During that year he was anointed as head of the Radical Committee of the province of Buenos Aires. In March 1881 He was appointed holder of the chairs of Argentine History and Civic Instruction at the Normal School for Teachers. The exercise of such a chair over five decades influenced him significantly, since the study and exposition of the history of his country gave him a global vision of the problems of his nation.

In 1889, Yrigoyen moved into his own house, in front of what is now Plaza Congreso in the City of Buenos Aires, on the street that currently bears his name, at the height of 1600. Shortly before moving, his brother Roque passed away after suffering a long illness. This fact caused him to lock himself even more in his muteness and he had to suffer a religious crisis. Little else is known of this due to the secretive nature of his life. During his brother's illness, he established a certain friendship with two of his friends, Carlos Pellegrini and Roque Sáenz Peña, who would have a lot to do with the institutional changes that ended up leading Hipólito Yrigoyen to the Presidency of the Nation.

Armed struggle

On April 10, 1892, there were presidential elections, which brought Luis Sáenz Peña to the presidency. A week before, President Carlos Pellegrini had declared a state of siege and, using the excuse of a radical conspiracy, ordered Leandro N. Alem to be jailed and practically all the radical leaders were imprisoned for two months, with the exception of Yrigoyen. In November of that year, the National Convention of the Radical Civic Union met, in which Alem read a report and Yrigoyen issued a statement calling to rise up in arms against the regime. Thus the Convention approved a manifesto that described the government as "arising from fraud and violence." Immediately afterwards, on November 17, the organic charter was sanctioned, the first document of its kind in the party's history.

This year began the successive events that led to a new radical revolution. On July 29, 1893, the government of San Luis was deposed by Juan Sáa, and on the 31st, after a day of bloody struggle, they took Rosario. Meanwhile, in Buenos Aires, Yrigoyen decided to put his plan into practice. Several leaders left the city to go to the interior of the province, each of whom had a specific task assigned to carry out the new rebellion. He gathered his friends and some of his laborers, some sixty people in all, at his ranch "El Trigo" (near Las Flores), and they headed for the Las Flores police station, which they took without resistance.

He arrived in Temperley on August 3 in the morning with 1,200 men and there he installed the headquarters of the revolution, directed and organized by Marcelo T. de Alvear. The camp came to house 2,800 armed citizens, who arrived in columns that came from taking neighboring towns. On August 4, the leader of the rebellion created several battalions to defend his settlement in Temperley, whose forces amounted to 4,500 men divided into eighteen battalions. Faced with this situation, the governor resigned that same day. Two days later, the Provincial Committee was formed, chaired by Yrigoyen, which met in Lomas de Zamora with the presence of some sixty members. Domingo Demaría asked that Yrigoyen be the provisional governor of the province, but he flatly refused, considering that he had participated in the revolution to end an illegal government, not to establish another. At the insistence of his co-religionists, he said: "Neither provisionally nor definitively."

After a crisis in the ministry that caused the resignation of several officials, Luis Sáenz Peña on July 3, 1893 called Aristóbulo del Valle -who had retired from political life after the division of the Civic Union- to reorganize it Del Valle first tried to invite the UCR Committee to participate in the new ministry, without success. He then tried to call some radical personalities to join some of the ministries, but they all flatly rejected the offer. He commanded a project to disarm the paramilitary forces that existed in some provinces that the governors used to retain their power in them. In addition, he sent Congress a series of interventions in the provinces of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, and San Luis, the provinces where power was largely controlled by the oligarchy. Given his position close to the government, del Valle could have carried out a coup. State against the government as Alem requested, but his legal convictions prevented him from taking such action even if it meant the failure of the revolution.

On August 8, a railway formation left Temperley to take La Plata. Colonel Martín Yrigoyen (Hipólito's brother) led 3,500 civilians who, after some war actions, evicted Governor Carlos Costa and took the city of La Plata. Colonel Yrigoyen's men were joined by reinforcements commanded by his brother, and around 4,500 people paraded through the streets of 13 and 44. Martín and Hipólito led the revolutionary troop, which was cheered by the people of La Plata. They decided to use the racetrack near the train station as a camp. Thus ended the takeover of La Plata, which took place peacefully. That same day the Province Committee met in Lomas de Zamora to elect the provisional governor, and Juan Carlos Belgrano was appointed, who elected Marcelo T. de Alvear to occupy the Ministry of Public Works. The provisional government would last only nine days. When the national government sent troops to intervene, Belgrano did not resist and handed over power to the inspector Eduardo Olivera.

The national government appointed Manuel Quintana Minister of the Interior, and he commanded a powerful military force in order to disrupt the revolution. On August 25, the Provincial Committee issued a manifesto laying down its arms. Alem insisted on ordering a new uprising throughout the country, but Yrigoyen refused as he thought that Quintana would use any means to stifle the revolution. And this is where the relationship between the two leaders begins to diminish. By October the revolution had been totally defeated. An emissary told Yrigoyen that they were going to arrest him and, when he was leaving his house at dawn, a police commission stopped him, thus he was arrested for the first time in his life. They transferred him to an old warship and later to a slightly flooded pontoon where several radicals were imprisoned, where he suffers dizziness due to poor hygienic conditions. Shortly after, the prisoners were deported to Montevideo, a city where he remained until December and which would be the only foreign land he knew in his entire life, and he would return to it many years later when he would be overthrown.

It was on the eve of this revolution that Yrigoyen met Alvear, more precisely when a police chief was being sought for the city of Buenos Aires. Aristóbulo del Valle proposed a relative of Alem's, who had been a commissioner. Thus he came into contact with Alvear and other personalities of civility such as Le Breton, Apellániz and Senillosa. Alvear and Yrigoyen continued to see each other at the Café de París and in committee meetings. He would always have a special appreciation for Alvear, even in the last years of the caudillo's life, when years before both radical leaders were in conflict.

As an anecdotal fact between both leaders, it can be mentioned that in 1897 Lisandro de la Torre challenged Yrigoyen to a fencing duel. Alvear had a few days to teach his friend some basic aspects of fencing, since he was unaware of that discipline while de la Torre was an expert. The duel took place on September 6 and Yrigoyen inflicted several cuts on de la Torre's face and emerged victorious. During his presidency he continued practicing fencing, a hobby that he would not abandon even as a septuagenarian. In 1897 he entered hockey Club and was there a few times, but after 1900 he did not set foot in the institution again, but he remained a member until his death.

On July 1, 1896, Leandro Alem committed suicide in the middle of the street. Aristóbulo del Valle had died prematurely in January of that year, so the leadership of the party fell even more to Yrigoyen. But, during the night of Alem's wake, he announced that the loss was too serious to be able to think of new projects, and asked those present to return to their provinces of origin until further notice.

When the National Convention of the UCR sanctioned on September 6, 1897 the so-called policy of the parallels to contest elections together with the mitristas, after a meeting of the provincial committee of the UCR on September 29 On September 1, at Alvear's house, they voted for the dissolution of said organization in order to thwart the strategy of the bernardistas. Since then, radicalism would enter a state of disorganization until the party reorganization of 1904.

He strongly disagreed with the pact with Mitrismo imposed by the president of the National Committee, Bernardo de Irigoyen, as a tactic to confront Julio Argentino Roca, when he was on his way to his second presidency in 1898.

Revolution of 1905

The first days of February 1905 had been designated for the beginning of the new radical revolution, and at the end of January the delegates left for their destinations to start the revolt. But both the Government and the police suspected that there were conspiracy plans, so they raided several buildings and, when civilians went to look for weapons, they ended up detained by the police. Alerted, General Smith went alone to the war arsenal and entered through the 10th Infantry Regiment. He quickly took charge of the unit, fortifying it with machine guns in the face of the possible revolutionary threat. Thirty-five unarmed people entered the barracks at 4 in the morning, when they asked for Martín Yrigoyen they were arrested. The failure to take over the arsenal ruined any revolutionary attempt, since the civilians were going to go there to provide themselves with weapons. Even so, the revolution continued its course: some 70 buildings were taken to convert them into cantons, some resisted many attacks, to the point that, for example, Bolívar and Brazil surrendered only when threatened with cannons.

At 3:45, President Manuel Quintana arrived at the Government House to urgently convene the cabinet, a state of siege was declared throughout the country. While there were uprisings in Bahía Blanca, Mendoza, Córdoba and Rosario, the capital was being successfully controlled by the government. Inside, the revolution had been successful: in Mendoza the garrison, the 1st artillery, the 1st cavalry and the 2nd cazadores' depot gave arms to the civilian groups. It was in the Government House where the strongest combat took place, since the soldiers who defended the governor resisted under a heavy firefight in the building until entering at noon. When the governor laid down his arms, after being threatened with the cannons of the 1st artillery, José Néstor Lencinas, head of the Revolutionary Junta, took charge of the provisional government. In Córdoba, the 8th Infantry had attacked the Police Department, after a strong attack a provisional government was established. Roca's son and several government leaders who happened to be in Córdoba. Del Valle tried to capture Roca, but he managed to escape to Santiago del Estero. In La Plata there was a series of suspicious movements, but the revolution did not break out. Several leaders escaped to Chile or Uruguay, but some like Del Valle were captured when they tried to leave the country, others turned themselves in. The civilian prisoners were confined in an army transport called Santa Cruz, totaling about seventy overcrowded and malnourished prisoners. As a means of entertainment, the detainees made two newspapers: El presionero and Don Hipólito. On March 5, the Executive Branch extended the state of siege for another seventy days, the military prisoners were promptly tried with sentences of up to eight years in prison, and on May 2 they were taken to the Patria transport bound for to Ushuaia.

Yrigoyen had remained anonymous during the last weeks of the uprising. It was announced that at the end of February he would appear in Federal Court. On February 28, a large crowd waited for him at the place, under a large police presence, but he did not appear, and the Government ended up exonerating him for "reasons of better service." Yrigoyen helped the exiles financially thanks to to subdivision and sale of their ranches. A few months after the end of the revolution, a civic association called "Asociación de Mayo" which started a pro-amnesty movement that had the support of the National Party of Uruguay. Yrigoyen took steps to have the arrested people released, but he ran into Quintana's inflexibility. But in March 1906 Quintana died and José Figueroa Alcorta, a member of the PAN modernist current, assumed the presidency, who promulgated an amnesty law, proposed among others by former president Carlos Pellegrini. and 1908 to urge him to promote fair elections, but with little success. Yrigoyen revealed these conversations at the 1909 Convention.

For the presidential elections of 1910, the National Autonomist Party chose as its candidate for president the leader of the modernist current, Roque Sáenz Peña. Sáenz Peña was in favor of establishing an electoral regime that would prevent fraud, and he was not only a friend of Yrigoyen, but also, thirty years earlier, both had been part of the group that founded the fleeting Republican Party.

Road to electoral reform

The beginning of the long-delayed political change occurred with the arrival to the presidency of Roque Sáenz Peña, an internal opponent of the National Autonomist Party. He focused all his government efforts on enacting a law to guarantee secret, universal and compulsory elections for all citizens. After overcoming the resistance of the conservatives who were most opposed to the exercise of full democracy, his project became the so-called Sáenz Peña law. The problem of suffrage was addressed with three laws, No. 4161 of December 29, 1902, which made it possible for the Socialist Party to have its first representation; No. 4578 of July 24, 1905, intended to calm the revolution of that year, and the famous Sáenz Peña Law (No. 8871), promulgated on February 10, 1912. Although this was predictable, it is noteworthy the attitude of President Roque Sáenz Peña, who responded to popular demands even knowing that this seriously affected conservative hegemony. However, it should be noted that the new law only covered elections for national offices, that is, for president and vice president, national deputies and national senators for the Federal Capital. Other elections continued to be held according to provincial laws. However, in 1912 federal intervention took place in the province of Santa Fe, and the controller organized the elections for governor and legislators in accordance with the new electoral reform. The UCR decided to participate and achieved victory. Thus, he took Manuel Menchaca to the governorship, the first governor elected by the law of secret elections.

At the beginning of March 1916, the National Committee of the Radical Civic Union met in order to convene a Convention, which took place on March 20 at the Casa Suiza with an attendance of 138 delegates. The session ended with the appointment of a commission made up of delegates Vicente Gallo, José Camilo Crotto, Pelagio Luna, José Saravia and Isaías Amado. At the same time, another commission was appointed, made up of Eudoro Vargas Gómez, Crotto, Luna and Marcelo T. de Alvear, to interview President Victorino de La Plaza with the aim of demanding a clean and free electoral act. The next day, while the first commission was debating about putting the Constitution into effect after years of institutional madness, the commission that went to interview De la Plaza did not return with encouraging news. This fact ended up dividing opinions within the body of delegates., so the session was adjourned to continue on March 22 at the Onrubia Theater, where the candidates for president and vice president were also to be elected.

Since eight in the morning the theater was full of people and nervousness reigned because, despite the fact that it was known that Yrigoyen would win by unanimous support, the delegates knew that he would renounce the candidacy. Regarding the vice presidency, there were demands by the "blue" group to integrate part of the binomial, and finally Pelagio Luna from La Rioja was appointed candidate for vice presidency. Voting began at 10:30 in the morning; Yrigoyen obtained one hundred and fifty votes, Leopoldo Melo two, and Alvear, Crotto and Gallo one each. Crotto rejected the vote they had given him, confirming that only Yrigoyen could be the indicated candidate. Then the vice-presidential candidate was elected, and Luna was elected with 81 votes against Gallo's 59, while Joaquín Castellanos y Melo they got one each. They went to an intermediate room to wait for the acceptance of the candidacies and, meanwhile, a demonstration gathered at Yrigoyen's house, but there were no signs that anyone was inside. Yrigoyen had gone to receive the Board of Directors of the Convention in Dr. Crotto's legal study on Avenida de Mayo, and there he expressed his intention to renounce his candidacy. Crotto then proposed forming a commission to interview Yrigoyen in order to convince him to accept the candidacy. The designated delegates Guido and Oyhanarte went, then, to the residence of Brasil 1039 and told Yrigoyen that, if he renounced such a candidacy, the fight would be terminated. Horacio Oyhanarte, present during that episode, recounts that:

In that short interval of time, all the foreheads pale, and upon the abrokish hearts transmigrated as a pilgrimage of lights and shadows, all our history... He was there, in the small room as a strife, as in the ranch of Tucumán; as in the old Colonial Cabildo, as in the Agora of Paraná; there he was solving the future destiny of the Republic. And when upon the emotion of all the spirits, which shone wet in the eyelids, he resonated the phrase to be left and that it was the sure advance of triumph: 'do from me what you want', the two-year blonds had just demarcated, the magna contend was determined, and the sacred banner, he beckoned by the arm of the strongest, he envalentonated all the breasts.Horatio Oyhanarte.

At half past seven in the evening the caudillo accepted. The news produced a congregation in front of the house at Brasil 1039.

1916 Presidential Election

The presidential elections of April 2, 1916 were the first in Argentine history to adopt the Sáenz Peña law, which guaranteed secret and compulsory voting for men, which is why it is considered the first democratic government in Argentine history, with the clarification that the first fully democratic government was the second presidency of Juan Domingo Perón in 1951, when women were able to exercise their right to vote and be voted for.

The first effects of the law were surprising for the reformists: radicals, socialists and league members prevailed in almost the entire modern strip of the country with the sole exception of the province of Buenos Aires, tightly controlled by the traditional political apparatus. The nucleated provincial parties that controlled the old regime failed to assemble a modern conservative political force. At the moment, the new norm did not introduce spectacular changes, neither in the electoral participation, nor in the campaigns or debates, while the new electoral practices coexisted with old norms. The electoral result was ambiguous since the composition of the Electoral College did not produce an undisputed winner when it met in 1916. Historian Luis Alberto Romero points out that something had truly changed when "some 100,000 people accompanied the new president on his way from Congress to Government House. The opponents were scandalized by the presence of the "rabble in espadrilles", a prejudice, certainly, but which testified to the beginning of a new era of democracy."

The Hipólito Yrigoyen-Pelagio Luna formula prevailed, beating the Conservative Party formula (Ángel Rojas-Juan Eugenio Serú) with 339,332 votes against 153,406 for the Conservative Party. He also won the electoral college with 152 votes. After taking an oath before the Legislative Assembly, the new president was literally taken by an avalanche of people to the Casa Rosada, without any type of personal custody. With thirteen voters missing to approve the triumph of radicalism, the conservatives went to Santa Fe to try to persuade voters who were at odds with the party authority. When asked about this fact, Yrigoyen said the famous phrase: "May a thousand governments be lost before violating our principles." Congress was made up of 45 radicals and 70 opponents in the Chamber of Deputies, while in the Senate there were only 4 radicals and 26 opponents. A total of eleven provinces were still represented by members of the previous regime.

The ambassador of Spain in Argentina attended on behalf of his country and wrote the following lines for the newspaper La Época:

In my diplomatic career I have attended famous celebrations in different European courts; I have witnessed the ascension of a president in France and a king of England; I have seen many extraordinary popular shows for his number and his enthusiasm. But I do not remember anything comparable to that master scene of a president who surrenders himself in the arms of his people, led between the cranks of the electrified crowd, to the high sitial of the first magistratura of his homeland (...). But all this was to be pale in the face of the reality of the immense square, of the human ocean mad of joy; of the man president delivered in body and soul to the expressions of his people, without guards, without army, without polyzonts.

Yrigoyen had suggested at the time to President Figueroa Alcorta the intervention of fourteen federal states where the fraud was still located, a practice still in force after the creation of the League of Governors, whose main mentors were Miguel Juárez Celman and Julio Argentino Rock. Federal interventions, called "civic hygiene," were carried out slowly by decrees of the executive branch in times of legislative recess. With the exception of the provinces governed by radicals, who had legitimately obtained power, the rest were intervened. The purpose of the intervention was to call legal elections and whatever the result, the winner would obtain the governorship. In many districts radicalism triumphed; However, in provinces such as Corrientes and San Luis, the conservatives prevailed, and in those cases the popular decision was respected. Nor had the provinces of Santa Fe, Buenos Aires and Jujuy been intervened.

The electoral triumph meant that, for the first time, a broad social sector previously excluded from public leadership positions came to lead different state spheres. These were middle sectors, without great economic resources, or connections with the upper classes. The presence of officials "without a last name" was one of the favorite topics for jokes by the conservative press. During the first years of his government, Yrigoyen managed by means of decrees, since many of the initiatives that he sent to Congress did not prosper due to the still prevailing conservative majority. Only after the legislative elections of 1918 did the radicalismo obtain a majority in the lower chamber.

During Yrigoyen's first government, radicalism was in the minority in Congress: in the Chamber of Deputies, 101 members were radicals and 129 were opponents, while in the 58-member Senate only 2 were radicals. Even in the minority, Yrigoyen maintained an attitude that was not very prone to dialogue and negotiation, not only with the traditional conservative parties that controlled the Senate, but also with the new popular parties that gained prominence from the secret vote: the Socialist Party and the Progressive Democrat. He conceived of radicalism as a "redemptive religion" for "the Argentine liberation", he did not see himself as a boss but as an "apostle"; and he thought that the Radical Civic Union was not just another party but "the homeland itself":

I have guided everyone, and no one, guided me, at no time or in any circumstances. That is why I could give the Radical U.C., that is, to the homeland itself, a spirit and a strong conduct and the safe orientation of its path.Hippolyte Yrigoyen, My life and my doctrine.

Legislative elections of 1918 and 1920

In the legislative elections held in 1918, the UCR obtained 367,263 votes, while in those held in 1920 the total number of votes was 338,723. Despite the fact that the UCR won a considerable number of seats in the national legislature, the constitutional slowness in renewing the upper house prevented it from representing what the electorate had chosen. The death of Pelagio Luna in June 1919, who exerted a notable influence on the body, and the fact that several radical senators were not within the government line, were some of the factors that led to several government initiatives being stopped in the Senate..

First Presidency (1916-1922)

He was the first president to maintain a nationalist line, convinced that the country had to manage its own currency and its credit, and, above all, it should have control of its transportation and its energy and oil exploitation networks. For this, he projected a state Central Bank, in order to nationalize foreign trade, managed by the cereal exporters, founded YPF and issued controls to the concessions of foreign companies that managed the railways. The historian of radicalism Gabriel del Mazo says that the government de Yrigoyen was characterized by his "Land and Oil Plan". In addition to defending the national patrimony, Yrigoyen tried to contain the expansionism of the large foreign economic groups that operated in the country. Faced with the aggressive interventionist policy of the United States in Latin America, he defended the principle of non-intervention, going so far as to order in one case that the Argentine warships salute the flag of the Dominican Republic and not that of the United States, which they had hoisted. his on the island in the framework of the 1916 invasion.

In terms of railways, rigorous controls were imposed on the railways in the hands of the British, especially with regard to tariffs and the establishment of capital accounts. The work of the State Railways was also promoted, seeking the exit to the Pacific to facilitate the transport of productions from the northwest and southwest -center- of the country to reach Peru, Chile and Bolivia.

The initial impulse to conquer democratic rights was slowed down, since the UCR did not control the Senate or the governorship of many of the provinces. Yrigoyen resorted in several cases to federal intervention, which deepened the confrontation with the conservative sectors. During his first presidency there were twenty interventions in the provinces; only five were by law, and ten interventions were in provinces governed by radicals. The government argued that those provinces whose government had been chosen through elections prior to the electoral reform had illegitimate governance.

Economic policy

The economic expansion that Argentina experienced during the period known as the radical republic (1916-1930), with an average annual expansion of 8.1%, continues to be one of the cycles of greatest economic growth in the country to this day. Argentine history. However, Yrigoyen had to face the problems derived from the First World War in Argentina. His policy was to maintain neutrality, which implied in economic terms to continue supplying the allies, traditional customers. The warring nations demanded cheap food, such as some industrial items such as blankets and canned meat, whose exports tripled during the period. 1914 to 1920. On the other hand, exports of corn and refrigerated meat (better quality than canned) stagnated. At the same time, imports of industrial manufactures that were previously produced in Europe were stopped, since the countries participating in the war focused their resources on the war industry. This fact led to the emergence of industries to produce those products that were previously imported. Between 1914 and 1921 trade with the United States grew, since England and the other European countries had nothing to offer Argentina.

When the Great War began, President Victorino de la Plaza ordered the suspension of the delivery of gold in exchange for banknotes made by the Currency Board in 1889, as a palliative for the "banking panic" and to avoid capital flight. This allowed the Argentine currency to maintain a fixed support with respect to gold. Fourteen million pesos in gold that came from legations in Paris and London were repatriated, where it had been deposited as payment that European merchants delivered on behalf of Argentine exporters. Thanks to this, the Argentine peso came to have 80% gold backing for the purposes of the first Yrigoyen government. The government tried unsuccessfully to create the Bank of the Republic in 1917, a financial entity whose objective would be to regulate the economy and the national finance. During the five years, no debt titles were issued, and the external debt was reduced to 225,000,000 pesos, for which several public jobs were left vacant in order to reduce public spending. Congress did not go so far as to sanction the income tax, whose sanction the government requested in 1919. National Department of Labor, and also made up of a representative of each party in conflict, to reach a viable understanding between workers and employers. Also in 1919, a law was brought to Congress that regulated work in obrajes and yerbatales, since the conditions of the workers were inhumane. Thus, Law No. 11,728 was approved during the following Radical administration in 1925, but it would end up being vetoed by Marcelo T. de Alvear at the insistence of Congress.

International market prices began to decline very slowly from 1914, while the manufactured products that Argentina imported began to cost more in relation to the price of cereals. Thus, an increasingly difficult situation was created that led to a general economic crisis, whose greatest exponent was the year 1929, at the same time as the international crisis. An industry with little development, created during the First World War but compressed afterwards, a fiscal organization that obtained almost all its resources through customs duties, and an almost normally deficit budget characterized, among other aspects, the Argentine economy during the radical period of 1916 to 1930.

Railroads

During the period of Conservative hegemony, the concessions to the British railways were in many cases abusive, since many managers of these companies were important politicians and legislators. Concessions were secretly agreed upon in London for 40 years.

In railway matters, rigorous controls were imposed on the railways in the hands of the British, especially with regard to rates and fixing of capital accounts, since these companies maintained false accounting that allowed them to declare low profits and high costs. In addition, the work of Ferrocarriles del Estado was given impetus, seeking the exit to the Pacific to facilitate the transport of productions from the northwest and southwest —center— of the country to reach Peru, Chile and Bolivia. The concession was annulled in;km of roads under construction. Following the railway strike of 1917, the employers advised Yrigoyen to replace workers with machinists from the navy, but the president refused.

The railway businessmen decided to carry out a parliamentary maneuver so as not to lose part of their interests, and said initiative was the creation of a mixed railway company.

Education

The arrival of a democratically elected government instilled in the student body the idea that the old structures of the existing universities would be reformed according to the new democratic spirit that now presided over the country. The manifestos of the Córdoba Library and the Colegio Novecentista de Buenos Aires, the severe criticisms that the Ateneo Universitario de Buenos Aires formulated since 1916 against the current university state, were gestating a nascent reformist movement, which finally broke out in Córdoba with La university reform. For this reason, on June 15 a number of people, who had already been constituted in the University Federation of Córdoba since May, evicted the professorial congregation, proclaiming a general strike, occupying the university and launching the "manifesto to the free men of South America", which was written by Deodoro Roca, where the rupture of the last chain of colonialism, the last mental servitude of America, is announced.

The climate of student agitation soon spread to other houses of study. The Argentine University Federation (FUA) founded on April 11, 1918, convened the first National Congress of University Students that deliberated in Córdoba from July 20 to 31. In support of the Cordovan movement, a student strike was held throughout the country. In August, at the request of the Cordoba University Federation and the Argentine University Federation, the Executive Power intervened the University of Córdoba, the intervener being the Minister of Public Instruction. The movement was supported by personalities such as José Ingenieros, Alejandro Korn, Alfredo Palacios and Ricardo Rojas. And so, with the pressure in the environment, the Superior Council of the University of Buenos Aires carried out certain reforms that satisfied the desires of the reformist movement, although in a relative way. On July 31, Yrigoyen sent to Congress an organic bill for Public Instruction, which places the universities "within the new spirit. of the Executive Power to the sanction of the new reformist norms. A month later Yrigoyen decreed the reform of the Cordovan statutes. At the University of La Plata the process was more tedious, by June 1920 the claims of the students had not yet been resolved, there were some violent episodes as a consequence of the resistance of their authorities to the reform. It is noteworthy that the new statutes were drafted by the presidents of the La Plata University Federation (FULP) and the Argentine University Federation, and adopted practically verbatim by the Executive Power.

In 1919, Law 10,861 was sanctioned by the President, creating the National University of the Litoral, responding to a long desire of young people who wanted to be educated in that area. The statutes were written in consultation with the student unions, and they were approved in April 1922. For this reason, this new university on the Litoral became known as the "universidad de la reforma". In Tucumán, the weak provincial institution was nationalized by means of Law 11,027 in 1920 at the request of the Argentine University Federation, which thereby complied with a resolution of the Congress of Córdoba. The act of Constitution of the Northern University was signed by the students, and a young reformist was appointed in charge of it: shortly after, statutes similar to those of the Universidad del Litoral were approved for his government. The movement expanded in some American universities too.

The Reformation was the starting point of an American generation who with that banner could feel strong enough to create a cultural order that was attentive to the earth, opening the university to the people and understanding the need to resist the oppression of imperialism and dictatorships to promote social structures free from injustice [...] The youth born to the heat of the Reformation was the vanguard of the American peoples against the dictatorships that infested our America at that time.Felix Luna.

But due to the measures promoted by the government tending to favor the student sectors, the reformists continued to view the popular government of Yrigoyen with suspicion, and even contributed to its fall in 1930.

On June 23, 1918 at the University of Córdoba, legislator Alfredo Palacios led a mobilization of ten thousand students called by the University Federation of Córdoba, which demanded changes in the study programs, resignation of teachers, modernization of the university system and a tripartite government made up of professors, students and graduates, a movement known as university reform, to which the University of La Plata joined shortly after. Yrigoyen viewed this movement sympathetically, which is why he created new houses of study so that the middle classes had greater access to the university. The reform implemented a student co-government to prevent abuses by the authorities. On April 11, 1918, the Argentine University Federation (FUA) was created, made up of students from cities such as Tucumán, Santa Fe, Córdoba, La Plata and Buenos Aires, and that same day Yrigoyen received the delegation of representatives elected by the students.. As Gabriel del Mazo explains:

His government belonged to the new spirit, which was identified with the fair aspirations of the students and that the University should be leveled with the state of consciousness achieved by the Republic.Gabriel del Mazo.

The president appointed José Nicolás Matienzo as controller, who was in charge of transforming the statutes of the University of Córdoba and established the election of new authorities. However, Dr. Nores, who was opposed to the reform, won, which provoked the opposition of the students and, given the failure of Matienzo's intervention, the students decided that the strike would be for an indefinite period. On June 21, 1918, a manifesto titled The Argentine youth of Córdoba was distributed to the free men of South America. In July 1918, the radical government sent a law to the National Congress that established the three levels of instruction. The University of the Coast was created, at the request of the National Congress of University Students, and the University of Tucumán was nationalized.

The university reform was projected in other Latin American countries. Precisely in the middle of 1920, Gabriel del Mazo, who presided over the FUA, signed an agreement with his counterpart from the Federation of Students of Peru in which they promised to fight for the support of popular universities, and the same thing happened in Mexico and Chile.

In the city of Buenos Aires, thirty-seven secondary schools and twelve arts and crafts institutes were founded. In addition, 3,126 primary schools were built throughout the entire Argentine territory. During the six years of government, school enrollment increased by more than four hundred thousand children. Illiteracy was reduced from 20% to 4%. The nocturnal baccalaureate was introduced, with a great concurrence of the working class. In this period the white overall was implemented, to socially equalize the students.

Oil Policy

When the First World War ended in 1918, an expansive period began for the nascent Argentine oil industry. Peace made it possible to normalize international trade and financial relations; Thus, it was possible to achieve greater availability of materials, equipment, freight and capital. At that time the internal combustion engine appeared, which caused a second industrial revolution and increased the demand for fuels. The expansion of automobiles as a means of transportation augured a sustained demand for petroleum products, mainly fuels, oils, and greases. In the aforementioned period, American and European companies also began to expand in search of reserves; these actions were endorsed by the government, concerned about having the much-required strategic mineral.

The government of Hipólito Yrigoyen announced the Land and Oil Plan, which gave the State a decisive intervention role. During his government, the largest company to exploit and market oil was created in 1922: YPF (Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales), and the recently elected president Marcelo T. de Alvear offered the leadership of this new company to the general and engineer Enrique Mosconi., who was the director of YPF between 1922 and 1930 and promoted the idea that: "The ownership of the subsoil is an inalienable right of the country." Mosconi set out to break with the trusts when, exercising the from the Army Aeronautics Service in 1922, West India Oil (a subcompany of Standard Oil of New Jersey) asked him to pay in advance for gasoline for airplanes. Some cities such as Comodoro Rivadavia, in Chubut, Plaza Huincul, in Neuquén, Las Heras, Cañadón Seco and Caleta Olivia, in Santa Cruz settled due to the proximity of the deposits.

Two months after assuming the presidency, the government requested authorization from Congress to make a loan of one hundred billion pesos for various measures, including promoting the exploitation of YPF. In 1919, the president sent Congress a thirteen-chapter project detailing the legal, technical, economic, and financial regime of oil. The purpose of the project was the principle of state ownership of the deposits. Days later, another project was added to this project that declared all the elements necessary for the exploitation of oil to be of public utility. But these initiatives would be blocked for a time in Congress. In 1921 the Executive Branch sent a message to Congress insisting that the aforementioned projects be sanctioned, but the message did not work. Given this, Yrigoyen issued a decree that created the General Directorate of YPF as a dependency of the Ministry of Agriculture. Despite his remarkable oil work, Yrigoyen failed to nationalize hydrocarbons, but he laid the foundations to avoid agreements that would negatively affect independence local economy.

In 1919 the following speech by the president was read in Congress:

It is therefore reserved for the state, because of the incorporation of these oil mines into its private domain, the right to monitor any exploitation of this source of public wealth, in order to prevent the particular interest from wasting it, that ignorance or precipitation perjudged it, or negligence or economic incapacity to leave it unproductive, for which provisions are adopted in the project that establish and guarantee a minimum of work and guarantee. With the same concept, the potential disruptive action of large monopolies is hindered.Hippolyte Yrigoyen, Congress of the Nation, 1919.

By 1914, the fuel pumping stations were distributed mainly between the Energina and Wico companies, English and American respectively, and in that same year the first pump was installed in Plaza Lorea. The installation of these foreign companies was enabled by an ordinance of December 1915, which prohibited two pumps from being placed within four hundred meters. However, by 1917 there was a monopoly of the American company West India Oil Company (WICO)., which sold 95% of the kerosene and 80% of the gasoline, in addition to having a monopoly on the supply of pumps in the city of Buenos Aires.

Social Policy

The union organizations, persecuted during the previous regime, were now hierarchical and collaborated with the authorities to solve workers' claims. Yrigoyen did not accept the Marxist concept of class struggle, but rather thought that they could work together for the good of the Nation. In most cases the strikes were respected, not repressed, and in many cases the demands of the protesters were met. When the railroad strike of 1917 occurred, the bosses advised the president to replace the workers with machinists from the navy, but the president refused and accepted the right to strike. He promoted the sanction of labor laws and sent Congress in 1921 a draft Labor Code, in a sense that coincides with the claims that the socialists and the labor movement had been making for decades. He also acted as a mediator in numerous labor conflicts, promoting the negotiation of agreements based on social justice. But, on the other hand, it maintained very conflictive relations with the Socialist Party, which had an important parliamentary representation, and with the majority sector of the labor movement, to which it denied its right to represent the Argentine workers in the act of constitution of the ILO. in 1919, for which the Argentine government was seriously reprimanded by the international organization.

In 1920 the labor unions, especially the Argentine Regional Workers' Federation of the IX, sent delegates to conciliation commissions and helped to dissipate the tension in certain strikes thanks to the request of the authorities. This modality of the FORA gave it support from the working class, which in 1915 had 51 unions and 20,000 pesos in annual contributions, a figure that in 1920 had risen to 734 unions with contributions of 700,000 pesos. The agricultural workers were organized by FORA, which in 1920 held an act in solidarity with the Argentine Agrarian Federation. The yerbatales workers who were victims of exploitation carried out their first strikes between 1918 and 1919, and managed to obtain labor improvements such as an 8-hour day and Sunday rest. The labor reforms of the first radical government produced an improvement in the average wage, which in 1916 was 3.60 pesos and in 1921 had risen to 6.75. The working day, which in 1916 was almost 9 hours, was reduced in 1921 to eight hours. The sum of the payments for compensation for work accidents was 282,000,000 in 1916, and 1,328,000,000 in 1921. Also, while the insured workers in 1916 were 200,000, this figure reached 465,000 in 1921.

During the first radical administration, union members increased exponentially. Whereas in 1916 there were only 70 guilds, four years later the number had risen to 750; As for the affiliates, from 40,000 at the beginning of the Yrigoyen government, it rose to 700,000 in 1920. Since 1915, the FORA of the Ninth Congress and the FORA of the Fifth Congress dominated the labor organizations. Between 1914 and 1918 it was greater the number of emigrants than the number of immigrants, since many returned to their homelands to fight in World War I. By 1919 many of those people who had gone to Europe returned to the country. The enormous influx of agricultural colonies, the proliferation of farms, the intensification of crops by the system of sharecroppers, the urban location of commerce and incipient industries made it necessary to address various interlinked rural and urban problems: agrarian reform and labor issues.

The Ministry of Agriculture reorganized the administration of public land, and several studies of the concessions of large areas of land by previous governments were initiated. Agronomist technicians were hired who toured and examined the national territory, checking property titles, and cataloging the exploitation possibilities of each lot. As a result of this study, by 1921 concessions had been revoked in an extension of almost eight million hectares. By means of a decree, those who had obtained land illegally were required to vacate it within a non-extendable period of two years, in addition to having to pay a fee for the period during which they had used the land illegally.

In certain sectors there were shortages as a result of commercial speculation. For this reason, the government sent Congress a regulation to expropriate 200,000 tons of sugar from hoarders, with the aim of distributing it to the population at normal prices. The law was approved in the Senate after arduous debates.

Retirement funds were created for workers and employees of public services such as gas, electricity, telegraph and telephone as well as for railway workers, and by means of Law No. 11,110 the retirement system for employees and workers of private utility companies. In 1921, thanks to Law no. general. With Law 10,505 enacted in 1918, home work was regulated, while Law No. 10,903 created the Board of Minors and the regime for the protection of minors. In 1917, Law no..

Although he tried unsuccessfully to promote a series of agrarian reforms —as was the case of the Banco Agrícola— some notable policies did materialize. Public lands had been the greatest desire of the Argentine oligarchic class. Railroad owners had profited by acquiring land around their railroads under an 1862 law, and then reselling it at higher prices to land companies that were nothing more than side companies. Yrigoyen was opposed to continuing to sell public land, as he wanted to protect this source of wealth for the State. Thus, the government forced the owners who had illegally occupied the land to return it, in addition to paying a fee for the time they had used it. The Banco Agrícola was created to safeguard the interests of farmers, but the initiative did not prosper; instead, the interests of the farmers were left in charge of the National Mortgage Bank, which achieved unusual development. The branches of Banco Hipotecario Nacional grew from twenty-two branches and four agencies at the beginning of the government to forty branches and forty-one branches by the end of the Yrigoyen government. Deputies Francisco Beiró and Carlos J. Rodríguez presented a project known as the Land Law Idle, which made them lose the right to those lands that had not been used in fifteen years, thus preventing the upper classes from having large fields in their possession for long periods of time. But the regulations did not prosper either. Law no. 11,170 on the rural lease regime was also sanctioned in 1921, based on the modifications introduced in the Civil Code by law no. 11,156. This regime would be modified in 1933 to ensure the protection of the lessee.

Shortly after the first government of Yrigoyen began, the socialist revolution broke out in Russia, and this historical event had a great effect on the worker sectors, who saw the perspective of a global transformation of the relations between capital and labor. Strikes began to occur more frequently, due to layoffs that occurred in industrial sectors due to the compression of emerging industries during World War I. The Patagonia workers' strike, harshly repressed by Héctor Varela, made an impression on the working classes, despite the poor news that came through the newspapers. Another general strike that broke out in Buenos Aires in 1919 shocked the country due to the unusual seriousness of the events. The strike, carried out by metallurgical workers, was harshly suppressed by police forces and extreme right-wing groups such as the Argentine Patriotic League and the Labor Association, events known as the tragic week. Real wages fell until 1918, which caused the number of strikes to increase, which went from 80 in 1916 to 367 the following year, to drop to 206 in 1920. The number of strikers was 24,000 in 1916, while in 1919 it reached 308,000 and fell to 134,000 in 1920.

During Yrigoyen's five years, public liberties as well as the freedom of public opinion as an expression of citizenship were never harmed. This is how the newspapers, despite the fact that they were mostly opponents (and critics of the president) never suffered acts of censorship or defamation. Ricardo Balbín would say about it: "Sometimes I reread them and I shudder to think that a citizen could say under his signature, in the newspapers of the Republic, things against the president, without being persecuted or accused."

Worker massacres

Tragic week

The economic consequences of World War I produced hundreds of strikes and violent confrontations during the Yrigoyen government. A series of long stoppages affected the national economy, especially in the railway, port and metallurgical areas. In 1919, in the Vasena metallurgical workshops, one of the bloodiest confrontations in history took place, the well-known tragic week, when a strike began in December over wage demands and working hours.

On December 3, 1918, a strike was declared at the Talleres Vasena metallurgical company, the largest in the country. The bosses' intransigence in negotiating with the union and union militancy extended the strike for several weeks, with a large number of armed confrontations between strikers and strikebreakers. Many of its adherents were immigrants returning from Europe after World War I.

On January 7, 1919, the police repressed the strikers at the corner of Pepirí and Amancio Alcorta, murdering five people, and unleashing the town known as the Tragic Week. The following day, the FORA of the V Congress declared a general strike for January 9, in order to attend the burial of the dead, with the adhesion of unions from both centrals and the Socialist Party.

On January 9, the procession of the dead took place, from the places where they were held in Nueva Pompeya, to the Chacarita Cemetery. At various points along the way there were bloody clashes between workers, police officers and vigilante agents of the National Labor Association. During the confrontations, the radical leader Elpidio González, appointed by Yrigoyen two days earlier as police chief, tried to speak personally with a group of strikers, who responded by making him get out of their vehicle and burning his car. A platoon of soldiers and policemen had installed themselves in the cemetery and fired into the crowd, preventing the burial from taking place. The sources estimated the death toll that day at several dozen, with no casualties among the security forces. That same afternoon, Yrigoyen appointed General Luis Dellepiane as military governor of the city of Buenos Aires. The government announced that it had uncovered a conspiracy led entirely by foreigners labeled "extremists" seeking to take over the government, led by Jewish journalist Pinie Wald, who was savagely tortured. The government's announcement was later found to be false. The government also applied the Residence Law in the name of "social defense" and compliance with Law No. 7029 was adjusted.

That day, to repress the strikers, radical and military leaders organized an extreme right-wing parapolice shock force, made up of upper-class youth, which over the days would adopt the name of the Argentine Patriotic League and which, Backed by the police and military forces, they persecuted workers and Jews, murdering, raping and burning houses. There was looting of armories, destruction of churches and seizure of workshops. General Dellepiane commanded the troops to repel the rebellion, which lasted until January 14. In the course of the repression, the security forces and parapolice carried out the only pogrom in the Once neighborhood. (killing of Jews) carried out in the American continent.

According to the government, there were around 65 civilian deaths and 4 from the armed forces, although it never presented a list of them. According to the opposition and the historians who investigated the event, more than 700 people were killed, several dozen disappeared, including several children, and tens of thousands of detainees. It all ended when FORA decided to end the strike on January 14, after the government's decision to release the prisoners and reopen the union premises, and the owners of the Vasena Workshops accepted the union's list of demands.

Rebel Patagonia

Another act of extreme violence is known as Rebel Patagonia, when, in a rebellion in the province of Santa Cruz, Argentine Patagonia, between 1920 and 1921, a strike was organized against the exploitation of the workers by their employers, to demand labor improvements. In November 1920, the Sociedad Obrera de Río Gallegos, under the leadership of the anarchist Antonio Soto (influenced by the 1917 Russian Revolution), declared a strike for better wages and housing for rural laborers. Soon after, the strike spread to the entire province of Santa Cruz. The lands were occupied by activists, who took their employers hostage, without using violence, although pitched battles with the police were fought. Within this framework, the government sent Lieutenant Colonel Héctor Benigno Varela at the head of the regiment to try to mitigate the conflict. Héctor Benigno Varela spoke with the workers to reach an agreement, which normalized the situation. However, at the end of 1921 there was a sharp decline in the price of wool, which caused a significant amount of accumulated stock and caused a significant decrease in the price of the product. The biggest problem was that the workers had an upcoming shearing, which made the situation worse. To avoid this, the workers took over the ranches again, again cautiously and without violence. Some owners even joined the claim as fair. But the strike ended up being repressed by the army under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Varela in command of two cavalry regiments.

Varela managed to capture ten Chilean policemen who were fighting alongside the strikers and were shooting at the Argentine soldiers; It should be noted that Patagonia was largely occupied by Chilean citizens. Varela demanded that the strikers return to their activities, promising improvements for them and their families; If they did not do so within a day, Varela said that he would force them and that he would shoot whoever shot his troops, and issued a resolution in which he said that any armed worker would be shot without further treatment. After the workers' negative response, hundreds of workers were shot, partly because Varela had not received precise instructions from the government. Hundreds of other workers were captured and imprisoned.

Dr. Viñas met with the president to tell him what happened in Patagonia and ask him to prosecute those responsible. But Yrigoyen did not want to do it since he thought that this would bring discredit to the armed forces and that the faith of the people in the institutions had to be saved even at the cost of impunity for some guilty parties.

International politics

Yrigoyen's international policy was the subject of strong discussions, even within radicalism. His policy basically defended the self-determination and equality of nations against the great powers.[citation needed] He followed the line of Victorino de la Plaza while maintaining neutrality in the First World War Worldwide, but with claims to the belligerent countries on both sides. When the steamer Curamalan was captured in Cardiff, he filed a claim with the French authorities, and the same thing happened when German ships and submarines damaged or even sank Argentine ships. Yrigoyen tried to convince other Latin American countries not to break relations with other nations without an important reason. For this reason, he called a conference of nations that was held in 1917 to pronounce themselves in favor of neutrality. But US opposition, added to the fact that Brazil had already broken relations with Berlin, made the attempt fail. Only Mexico and Colombia accepted the call of the Argentine government.

Yrigoyen sent a bill to cancel the debt that Paraguay had brought from the Triple Alliance war, but it did not prosper. The following radical government would return to deal with the issue.

In 1917, a group of protesters stormed and vandalized the German Club, the German Delegation, and the German Transatlantic Electricity Company. These facts, added to the news that the German minister in Buenos Aires, Karl von Luxburg, had sent secret telegrams in which he recommended sinking Argentine ships "without leaving traces" and in which he included insulting phrases towards Foreign Minister Honorio Pueyrredón, made Public opinion, like many radical leaders, pressured Yrigoyen to break diplomatic relations with Germany. But the president maintained neutrality. When German submarines sank the freighter Toro, near Gibraltar, and the merchant ship Monte Protegido, the Socialist deputies voted in Congress for Argentina to enter the war, but Yrigoyen refused. remained adamant.

Faced with the Treaty of Versailles and the creation of the League of Nations, the Argentine position was to maintain the separation between both acts: the Treaty was a matter that should be limited to the countries that had fought, while the League of Nations, on the contrary, it should be an egalitarian and voluntary association of all the nations of the world. In addition, Yrigoyen commissioned the Argentine representatives before the League of Nations to request that both victorious and defeated nations be treated equitably despite the opposition of some members of the league, such as Marcelo T. de Alvear and Fernando Pérez. The rejection of the Argentine position, fundamentally promoted by the European imperial nations, at a time when the peoples of Africa and Asia were still subject to European colonialism, led to the withdrawal of the Argentine delegation from the Society.

Yrigoyen tried to contain the expansionism of the large foreign economic groups that operated in the country. Faced with the aggressive interventionist policy of the United States in Latin America, he defended the principle of non-intervention; He even went so far as to order that the Argentine warships salute the flag of the Dominican Republic and not that of the United States, which had raised its flag on the island during the 1916 invasion.

1922 elections and activities after the first presidency

When the issue of a name for the 1922 presidential election arose, and the list of names was already becoming too long within the party, Yrigoyen decided to support Marcelo T. de Alvear. The election did not arouse major resistance within the party. Despite the fact that Alvear had had "rebellious" attitudes in the past, such as the episode in Geneva, Yrigoyen always showed appreciation for Alvear; In addition, he had shown great personal commitment in the radical revolutions of the past, contributing his efforts and fortune to the radical cause.

In February 1922, the National Committee was formed, arising from the reorganization carried out during the previous year. David Luna, national senator for La Rioja, was elected president, the former governor of Córdoba, Eufrasio Loza, first vice president, second vice president Eudoro Bargas Gómez, secretaries Santiago Corvalán and Jacinto Fernández, and Luis Catalá as treasurer. It was resolved to convene the National Convention for March 10 in order to proceed with the election of the presidential formula that the party would hold in the April 2 elections. In the interval between the meeting of the National Committee and the National Convention, a dissident faction that manifested itself as anti-yrigoyenista took shape.

On March 10, 1922, the UCR National Convention met at the Casa Suiza under the provisional presidency of David Luna. The following day the election was held at the Teatro Nuevo before an enthusiastic crowd. The first term of the presidential formula did not throw up major surprises, but instead there was some uncertainty in the second. The final scrutiny yielded 139 votes for Alvear over Fernando Saguier, who had 18. The vice presidency was won by Elpidio González by 102 votes against 28 for Ramón Gómez. Alvear was immediately informed by telegram of the results of the vote, since he was ambassador in Paris. The presidential elections were held on April 2, 1922, with a large victory for the radical candidate by 406,000 votes., against 123,000 votes for the conservative candidate.

On October 12, Yrigoyen hands over the sash and cane to Alvear at the Casa Rosada, with the face-to-face support of a large crowd gathered in the Plaza de Mayo. Yrigoyen wished the new ruler success and then, accompanied by his ministers and some of his friends, left for his house on Calle Brasil. Another large crowd of people showed up at his home to wait for him, making it somewhat difficult for him to get out of his car and get to his house. At night he was visited by Alvear. Alvear made a government with a different political content than Yrigoyen, both politically and administratively: Alvear gave his ministers more freedom, in an attempt to lead a government "a the European". In some specific cases, he took measures contrary to those of his predecessor Hipólito Yrigoyen, and appointed several of the main anti-Rigoyenist leaders as ministers, although he also maintained his autonomy when the anti-personalist radicals repeatedly asked him to intervene in Buenos Aires to win in 1928., and Alvear rejected the proposal.