Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegarde of Bingen (German: Hildegard von Bingen; Bermersheim vor der Höhe, Holy Roman Empire, 16 September 1098-Monastery Rupertsberg, September 17, 1179) was a German polymath and Benedictine saintly abbess, active as a composer, writer, philosopher, scientist, naturalist, physician, mystic, monastic leader, and prophetess during the Middle Ages. Also known as the Rhine sibyl and Teutonic prophetess, she is also one of the most famous composers of sacred monophony, as well as the most recorded in modern times. In addition, she is recognized for many experts as the mother of natural history.

Considered one of the most influential, multifaceted and fascinating personalities of the Late Middle Ages and Western history, she is also one of the most illustrious figures of female monasticism and perhaps the one who best exemplified the Benedictine ideal, being endowed with unusual intelligence and culture, committed to the Gregorian reform and being one of the most productive writers of her time.

Hildegarde's convent elected her as magistra (mother superior) in 1136. She founded the monasteries of Rupertsberg, in 1150, and of Eibingen, in 1165. In her production are theological, botanical and medicines, as well as letters, hymns, and antiphons for the liturgy. He wrote poems and supervised miniature illuminations in the Rupertsberg manuscript of his early work, Scivias. More chants of his composition survive than by any other composer throughout the Middle Ages, and he is one of the few composers known to have written both music and lyrics. One of his works, the Ordo Virtutum, is an early example of a liturgical drama and is probably the oldest surviving example of morality. He is also known for the invention of a constructed language known as Lingua Ignota.

Although the history of her canonization is complex, various branches of the Church have recognized her as a saint for centuries; On October 7, 2012, at the opening mass of the XIII Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops, Pope Benedict XVI granted her the title of Doctor of the Church together with Saint John of Avila., in recognition of "his holiness of life and the originality of his teachings". In the words of the philologist Victoria Cirlot:

[...] going through the wall of times his words have remained, even his sound, and the images of his visions.

Biography

His Early Years

Hildegarde was born in Bermersheim, in the Rhine Valley (present-day Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany), during the summer of 1098, into a wealthy German noble family. She was the youngest of Hildebert's ten children de Bermersheim, knight in the service of Meginhard, Count of Spanheim, and his wife, Matilda de Merxheim-Nahet, and for this reason she was considered a tithe to God, given as an Oblate and consecrated from birth to religious activity, according to the medieval mentality. In this way, she was dedicated by her parents to religious life and given for her education to Countess Judith of Spanheim (Jutta), daughter of Count Stephen II of Spanheim and, by as noble as she, who instructed her in reciting the psalter, in reading Latin —although he did not teach her to write it or, at least, not expertly—, in reading Sacred Scripture and in the Gregorian singing.

For some years teacher and student lived in the castle of Spanheim. When Hildegarda turned fourteen, they both cloistered themselves in the Disibodenberg monastery. This monastery was male, but it housed a small group of cloistered women in an adjoining cell, under the direction of Judith. The solemn closing ceremony was held on November 1, 1112 and Hildegarda, Judith and another cloistered woman participated in it, also an infant. In 1114, the cell was transformed into a small monastery, in order to accommodate the growing number of vocations. In that same year, Hildegard made her religious profession under Benedictine rule, receiving the veil from Bishop Otto of Bamberg, thus continuing her rudimentary monastic education directed by Judith.

Judith died in 1136, with a reputation for holiness after having led a life of great austerity and asceticism, which included long fasts and corporal penance. Hildegard, despite her youth, was elected abbess (magistra) unanimously by the community of nuns.

Visionary and writer

Since she was a child, Hildegarda had a weak physical constitution, suffered from constant illnesses and experienced visions. In a later hagiography written by the monk Theoderic of Echternach, the testimony of Hildegard herself was recorded, where she recorded that from the age of three she had a vision of "a light such that my soul trembled". These events continued even during the years in which he was under the instruction of Judith who, apparently, had knowledge of them. She experienced these episodes consciously, that is, without losing consciousness or suffering ecstasy.She described them as a great light in which images, shapes and colors were presented; They were also accompanied by a voice that explained what she saw and, in some cases, music.

In 1141, at the age of forty-two, a more powerful episode of visions occurred, during which she received a supernatural order to write down whatever visions she had from then on. From then on, she wrote down her experiences, which resulted in the first book, called Scivias (Know the ways), which was not completed until 1151. For this purpose, he hired one of the monks of Disibodenberg named Volmar and, as a collaborator, one of his nuns, named Ricardis de Stade.

Nevertheless, he continued to have reluctance to make his revelations and the texts resulting from them public, so to dispel his doubts he turned to one of the most prominent men with the greatest spiritual reputation of his time: Bernardo de Claraval, to whom he addressed a heartfelt letter asking for advice on the nature of his visions and the relevance of making them common knowledge. In said letter, sent around 1146, he confessed to the illustrious Cistercian monk that he had seen him in a vision "as a man who saw direct to the sun bold and without fear", and, at the same time that he attributed to himself "weakness", asked his advice:

[... ]Father, I am deeply disturbed by a vision that has appeared to me through a divine revelation and that I have not seen with my fleshly eyes, but only in my spirit. I have seen great wonders since my childhood that my tongue cannot express, but that the Spirit of God has taught me that I must believe. [...]

Through this vision, which touched my heart and soul as a burning flame, I was shown deep things. However, I did not receive these teachings in German, in which I have never had instruction. I can read at the most elementary level, but not fully understand it. Please give me your opinion on these things, for I am ignorant and without experience in material things and have only been instructed internally in my spirit. That's where my speech is hesitant. [...]Hildegarda to Bernardo, Abbot of Claraval.

Bernardo's response was neither very extensive nor as eloquent as the letter sent by Hildegarda, but in it he invited him to "recognize this gift as a grace and to respond to it eagerly with humility and devotion [...]». In addition, it seems that the abbot of Clairvaux later intervened with Pope Eugenio III in favor of Hildegarda, since he had personal contact with the bishop of Rome because he was also a Cistercian and a former disciple of his.

Precisely, Archbishop Enrique de Mainz, under whose jurisdiction the Disibodenberg monastery was located, and who was aware of Hildegarda's visions and prophecies, sent a commission to Pope Eugene to find out what happened and get him to declare about it. the nature of such gifts. The pope was in Trier at that time to preside over the synod that was held in that city between 1147 and 1148.

In 1148, a committee of theologians, headed by Alberus of Chiny-Namur, Bishop of Verdun, studied and approved, at the request of the pope, part of the Scivias. The pope himself publicly read some texts during the Synod of Trier and declared that such visions were the fruit of the intervention of the Holy Spirit. Upon approval, he sent a letter to Hildegard, asking her to continue writing his visions. With this, not only the canonically approved literary activity began, but also the epistolary relationship with multiple personalities of the time, both political and ecclesiastical, such as the aforementioned Bernardo de Claraval, Federico I Barbarossa, Henry II of England or Eleanor of Aquitaine., who asked for his advice and guidance. Such was her recognition that she became known as the Sibyl of the Rhine.

Founder

Also in 1148, and without having finished writing Scivias, a vision made her conceive the idea of leaving Disibodenberg and going to a place "where there was no water and where nothing was pleasant"., thus inspiring her to found a monastery on St. Rupert's Hill (Rupertsberg), near Bingen, west of the Rhine River, at the mouth of the Nahe, to move the growing community and emancipate her from the monks of Disibodenberg.

However, Kuno, then abbot of Disibodenberg, opposed her departure, which greatly annoyed the nun, to the point of causing her physical disorders, which were attributed to divine causes:

They said she had been deceived by vanity. When I heard it, my heart was afflicted, my flesh and my veins dried up, and for many days I lay in bed.Vita II, V

Faced with this situation, the Marchioness Ricardis de Stade (Richardis von Stade), mother of the nun who served as Hildegarda's secretary, intervened, who managed to convince Henry I, Archbishop of Mainz (1142– 1153), that he gave the authorization for the departure of the nuns and the foundation of the new monastery. About 1150, she moved to Rupertsberg with about twenty of her nuns, obtained the permission of Count Bernard of Hildesheim, owner of the chosen land, and founded the Rupertsberg monastery, of which she became abbess.

Around this time, her assistant and secretary Ricardis abandoned her to become abbess of the convent of Bassum in Saxony. This caused Hildegarda's sadness and opposition, which she would later reflect in serious letters of protest to Archbishop Hartwig of Bremen, Ricardis's brother, who had influenced her to obtain her abbatial position; he even appealed to the pope, without getting the nun to return. Ricardis died a year after the separation.

One year after the transfer, he finished Scivias, and his two books on natural sciences (Physica) and medicine (Cause et cure), in which he exposed a large amount of knowledge about the functioning of the human body, herbology and other medical treatments of his time based on the properties of stones and animals. He also began the collection of songs that titled Symphonia harmonie celestium revelationum, which he composed to meet the liturgical needs of his community. According to some chronologies, the start of the Liber vite meritorum would also date from 1150.

Around 1163, as a result of his constant visions, he began to write the Liber divinorum operum, the third of his three most important works and which would take around ten years to complete. However, the abbess herself alternated the contemplative and writing life with that of preaching and founding, since in 1165 she founded a second monastery in Eibingen, which she regularly visited twice a week.

Preaching and political intervention

The fame of the abbess as a saint and a prophetess was such that, in 1150, Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa himself invited her to meet with him in his palace in Ingelheim. The mutual appreciation generated by this interview, manifested in the subsequent letters, reached such a degree that, thirteen years later, the sovereign granted an edict of imperial protection in perpetuity to the Rupertsberg monastery.

Hildegarda's work as a writer was interrupted many times by preaching trips. Although her cloister in her time was not as rigid as it would be after Boniface VIII, she did not cease to surprise and admire her contemporaries that an abbess left her monastery to preach.

The content of his preaching revolved around the redemption, conversion and reform of the clergy, harshly criticizing ecclesiastical corruption, as well as firmly opposing the Cathars; By condemning their doctrines, he proposed combating their errors through preaching and the edification of the clergy.

In total there were four preaching trips he made: the first between 1158 and 1159, in which he traveled to Mainz and Wurzburg. In 1160 he carried out the second to Trier and to Metz. In his third preaching, between 1161 and 1163, he traveled up the Rhine to Cologne. In the last of his travels, between 1170 and 1171, he preached in the Swabian region.

In addition to these preaching tours, Hildegard used letters to make her point known to notable people. On the occasion of the schism caused by the election of the antipope Victor IV with the support of the emperor Barbarossa, against the Roman Pope Alexander III, prolonged to the death of Victor IV with the election of the also antipopes Pascual III and Calixto III, Hildegarda issued serious admonitions prophetic to the first of these, as well as to the emperor himself.

In the year 1173, shortly before concluding the Liber divinorum operum, the monk Volmar, her closest collaborator and secretary, died, which forced her to seek help from the monks of the abbey of Saint Eucharius of Trier to finish said work. For some time the monk Godfrey of Disibodenberg served as his scribe, while he began writing a biography of the prophetess, but he too died shortly afterwards, in 1176. The last of His secretaries found him in Guibert de Gembloux, a Flemish monk, with whom he had had an epistolary conversation initiated by his interest in the way in which Hildegarde had her visions.

Last Stand

The last critical situation Hildegard had to face occurred in 1178, when her community buried a supposedly excommunicated nobleman in the convent cemetery. Due to the imposition of this ecclesiastical penalty, canon law prohibited her burial on sacred ground. Hildegarda was asked to exhume her body. She refused and even made any trace of the burial disappear so that no one could search for it. She maintained that she had been reconciled to the Church before she died. The prelates of Mainz, in the absence of Archbishop Christian, who was in Rome, questioned the monastery. By him the use of bells, instruments and songs in the life and liturgy of Rupertsberg was prohibited. Hildegarda defended herself by writing a letter of rich doctrinal content, where she collected the theological meaning of music. When the archbishop returned in March 1179, witnesses came forward to support Hildegard's version and the interdict was lifted.

Death and veneration

A few months after the interdict was lifted, on September 17, 1179, Hildegarda died at the age of eighty-one. The hagiographic chronicles say that at the time of her death, two very bright arcs of different colors appeared that formed a cross in the sky.

Between 1180 and 1190, the monk Theoderic of Echternach wrote Hildegard's Vita (Life), collecting autobiographical passages that the nun had left and recounted. Gregory IX opened the canonization process in 1227, although it was not concluded. It was reopened by Innocent IV in 1244, without it being completed on this occasion either. However, due to the spread of her cult, she was inscribed in the Roman Martyrology, also including her name in some litanies; relics were removed from his grave; his liturgical feast was celebrated; miracles were attributed to him and pictorial and sculptural representations of him began to be venerated.

Her relics were kept in the Rupertsberg convent until its destruction in 1632, during the Thirty Years' War. They were then taken to Cologne and later to Ebingen, where they were deposited in the parish church, where they still rest.

In 1940 its celebration was officially approved for local churches. On the occasion of the 800th anniversary of her death, John Paul II referred to her as a prophetess and saint. In the same way, in 2006, Pope Benedict XVI also referred to Hildegard as a saint and praised her as one of the great women of Christianity along with Catherine of Siena, Teresa of Ávila and Mother Teresa of Calcutta.

In 2010, Pope Benedict XVI dedicated the General Audiences of September 1 and 8 to Hildegarda, within the framework of a series of catecheses on Christian writers, being the first woman to be featured in these catecheses; He recalled, among other things, that Hildegard's contemporaries regarded her with the title of "Teutonic prophetess" and pointed out the theological value of her writings and teachings.

In December 2011, Pope Benedict XVI announced his decision to grant Saint Hildegard the title of "Doctor of the Church". On May 10, 2012, he proceeded to inscribe her in the catalog of the saints and extend their liturgical worship to the universal Church, in an equivalent canonization. On May 27, 2012, during the Regina Caeli prayer on the day of Pentecost, the pope determined the date for the proclamation as a doctor. October 2012, during the opening Mass of the Synod of Bishops in Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome, the official proclamation was made by which she was granted the title of "Doctor for the Universal Church" together with Saint John of Avila. by Pope Benedict XVI.

Hildegarde is also venerated by some of the Churches that make up the Anglican Communion, including the Church of England and the Scottish Episcopal Church. In both the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion she is celebrated on 17 September.

Hildegarde's religious iconography is sparse, probably because her cult was local for quite some time. She is portrayed with the proper attributes of an abbess of the order of Saint Benedict: abbatial staff and Benedictine habit with a black and white veil; her oldest representations reproduce the way she appears in the miniatures of her writings: seated with a stylus in her hand in an attitude of writing on a pair of tablets or dictating to a monk, with five flames around her head representing divine vision. She later changes her style to a quill, with some scroll or book in hand—commonly the Scivias —and some musical instrument.

Work

The works of this nun from the 12th century were written —like most of the writings of her time— in Medieval Latin, except for certain annotations and words that can be found in some of his letters and mainly in his works related to Lingua ignota, which appear in medieval German typical of the Middle Franconian-Rhineland region/ Moselle. In her work, she herself accused on various occasions her little preparation in Latin, but from her own confessions and her hagiographers it is known that her writing method began by writing her visions and then passing them on to a secretary who corrected the errors and polished the writing Two of them —Volmar and Gottfried— were monks from Rupertsberg and the third, of Flemish origin —Guibert de Gembloux— was a monk from Gembloux Abbey, hence all of them were well prepared in ecclesiastical Latin.

He used various styles of writing: theological treatise, epistolary, hagiographic and medical treatise; but his visionary works stand out, in which he makes a constant and fruitful use of ethical-religious allegory, which, although it was quite common in his time, came to use infrequent symbols.

Regarding the influences received and his way of writing, undoubtedly the Holy Scriptures stand out through the Vulgate, with special attention to the prophets and the New Testament; in the latter, the importance that the Gospel of Saint John and the Apocalypse had on her stands out, since even in some autobiographical narratives recorded in the Vita she came to compare her spiritual gifts with the inspirations of the evangelist John added to the apocalyptic tone of the final parts of Scivias.

Knowledge of some works of Latin patristics is also attributed to him, among which the influence of Saint Augustine and Saint Isidoro of Seville has been detected; The influence and similarity with the Shepherd of Hermas and Boethius as sources of the allegorical identification as women that Hildegard makes of the Church and of some virtues in the Scivias have been especially pointed out. In addition, despite the fact that the abbess described herself as "uneducated", a great classical cultural background from Cicero, Lucan and Seneca has been detected in her works; she and Galen agree on some medical theories about humors; in the Scivias and the Ordo virtutum she represents the constant struggle of the virtues against the vices through her personification as women adorned with the attributes corresponding to the moral attitude they embody, combating each virtue against the vice opposite to it. This allegorical tradition is common to other medieval writers and can be traced back to Prudentius' Psychomachia in the fourth century .

Fonts

Her works were bequeathed to posterity thanks to the interest of the monks who admired her and helped her write them, led by Guibert de Gembloux, who after her death finished transcribing the works of the abbess, compiled them and illustrated them with miniatures. Among the most important medieval manuscripts that have been preserved, where the written and musical works of the Teutonic prophetess are contained, are:

Riesencodex

The Wiesbaden codex, known in German as the “Riesencodex” (Giant Codex) due to its large size (46 x 30 cm) and weight (15 kg), is a medieval manuscript of 481 pages, dating from the last years of Hildegard's life to some years after her death, the latest date being the year 1200. Originally, it was kept in Rupertsberg, but its artistic richness has led some researchers to doubt that it was created there or in Eibingen.

When the Rupertsberg convent was destroyed in the 17th century, the manuscript was transferred to the Eibingen monastery together with the relics of the saint In 1814, it was brought to the Wiesbaden Library (now the University and State Library of Rhein-Main). During World War II, the original manuscript was nearly destroyed, but its contents were preserved thanks to photocopies and facsimiles extracted during the first decades of the century XX.

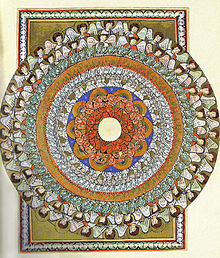

Contains a version of his three main mystical works: Scivias, Liber vite meritorum and Liber divinorum operum. It is also the source of all his musical compositions, his works on the Lengua ignota, hagiographic works (Vita sancti Ruperti), some letters, homilies and the Vita written by the monk Theoderic, making it the largest and most important source of the work of the medieval nun. Contains illustrations of the visions described by the abbess, inspired by those that illustrated her original manuscripts.

Other codices

- Ghent, University of Ghent Library, Cod. 241. It is the oldest manuscript known, whose creation dates from 1170 to 1173. It was probably written in the monastery of Rupertsberg. He went through a Benedictine monastery in Tréveris and then to Ghent, where he was guarded at the library of the University of Ghent. Contains a copy of Liber divinarum operum.

- Lucca, State Library, Ms. 1942. Dated to the centuryXIII in Renania. It is the source of the illustrations of Liber divinarum operum.

- Dendermonde, St.-Pieters & Paulusabdij Klosterbibliothek, Cod. 9. Known as Codice Villarenser or DendermondeIt is located in the library of the Abbey of Saint Peter and Paul. You think it was written about 1175. Contains a copy of the Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum, the Ordo virtutum and various songs; it is also one of the sources of Liber vite meritorum.

- Troyes, Municipal Library of Troyes, Ms. 683. Although with origins in the centuryXIIseveral stages of creation have been recognized. Its earliest parts are believed to come from Rupertsberg. It is related to the manuscript of Ghent, of which it appears to be a copy. It's another source of Liber divinarum operum.

- Berlin, Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Cod. theol. lat. Known as Berlin Codex or Codex CheltenhamensisIt is located at the Berlin State Library. Datable in the centuryXII or early 13th, contains some of the letters of the saint (Epistole), the Liber vite meritorum and its treaties on Lygua ignota.

Literary works

Of the religious works that Hildegarda wrote, three of a theological nature stand out: Scivias, on dogmatic theology; Liber vite meritorum, on moral theology; and Liber divinorum operum, on cosmology, anthropology and theodicy. This trilogy forms the largest corpus of her works and her thoughts.

The name Scivias is a shortened form of the Latin "Scito vias Domini", meaning "Know the ways of the Lord". This work was inspired by a vision that he was forty-two years old, that is, around 1141, in which he claimed to have attended a theophany that ordered him to write what he perceived:

Oh fragile human being, ash of ashes and rottenness: speak and write what you see and hear.Scivias (Protestificatio)

Divided into three books, in this work he describes the twenty-six visions he had, which are illustrated in the preserved manuscripts, serving as an allegory and a means of explaining the main dogmas of Catholicism and the Church in a more or less systematic. After the description of each vision loaded with complicated symbolism, the heavenly voice goes on to explain its meaning. In this way he covers the themes of "divine majesty, the Trinity, Creation, the fall of Lucifer and Adam, the stages of the history of salvation, the Church and the sacraments, the Last Judgment and the future world".

Liber vite meritorum

The Book of the Merits of Life, whose full title is Liber vite meritorum, per simplicem hominem a vivente lucem revelatorum, was written between 1158 and 1163. It is a work of a moral nature in which, starting from the vision of God as a cosmic man who sustains and vivifies the universe, Hildegarda came to an exposition of the main spiritual vices and their opposite virtues. This systematization corresponds natural aspects of the world and of man with the passions of the human soul. Said vision is explained throughout five books and is complemented by a sixth that details the description of the penalties that in the afterlife will correspond to each vice. In this way, the Liber vite meritorum becomes a catalog of thirty-five vices, described under the symbolic figure of allegorical beings made up of parts of beasts and humans.

The work offers one of the earliest historical representations of Christian purgatory, where each soul must atone for its debts before ascending to heaven. The descriptions given about the torments to be suffered are often grotesque and terrible, emphasizing the moralizing aspect of the work as a guide to conduct and virtue.

Liber divinorum operum

The Liber divinorum operum or Book of Divine Works was created between 1163 and 1173, when Hildegard was already in her sixties. It is the description of ten visions, where he makes a cosmology that structures the universe in correspondence with human physiology, and that converts the acts of man in parallel to the acts of God, through his active cooperation in the construction and order of the cosmos.

Thus, he also developed an explanation of the creative work of God, center of the universe, which unfolds in human time having its manifestation in the nature of the world and in history, with its maximum expression in the incarnation of Christ, Verb divine.

Unknown language

Another of her main works is the creation of her Lingua ignota, the first artificial language in history, for which she was named patron saint of Esperantists.

This language was exposed in his writing Ignota Lingua per simplicem hominem Hildegardem prolata, which has survived to this day integrated with other works in the Riesencodex, on folios 461 v–464v, as well as in that of Berlin, folios 57r–62r. The work is a glossary of 109 words written in that language with their meaning in German, including that of some plants and terms used in her medical works.

In both manuscripts there is also a small work known as Littere ignote (Unknown Letters), in which he presents twenty-three new letters, constituting a hitherto unknown alphabet, that although they bear some resemblance to the features of the Greek and Hebrew alphabet, Hildegard is not considered to have attempted to emulate them.

It has been proposed that its creation was mystical in nature, perhaps some kind of glossolalia. However, many of the words in that language seem to tend towards scientific interest. But there is no clear reason why he was created.

Scientific work

From the lavenderThe lavender is hot and dry, as it has a little sap. It does not serve the man to eat though he has a strong smell. The man who has many lice, if he smells lavender frequently, the lice will die. Its smell clarifies the eyes, because it contains in itself the virtues of the strongest spices and the bitterest. That's why it also takes away so many bad things and evil spirits get terrified by it. - Bingen's throat. PhysicaBook I, Cap. XXXV (Migne, PL. CXCVII, 1143) |

He also wrote works of a scientific nature: Liber simplicis medicine or Physica, is a work on medicine, divided into nine books on the corresponding curative properties of plants, elements, trees, stones, fish, birds, animals, reptiles and metals. The most extensive of such chapters is the first, dedicated to plants, which indicates that Hildegard had extensive knowledge in the therapeutic application of it from a holistic perspective. In this book she applies the widespread medieval medical theory of the humors, which she relates to the idea that the constitution of beings based on the divine plan is carried out through four constituent elements, whose balance determines the individual's health or illness.. Thus, each plant is given the corresponding qualifier of its quality: robustus, siccus, calidus, aridus, humidus, etc.

In turn, the Liber composite medicine, or Cause et cure, deals with the origin of diseases and their treatment.

Other writings

The authorship of around three hundred letters has been verified, where he touches on the most varied topics: theology, spirituality, politics, healing remedies, advice on monastic and clerical life, among other matters that he was consulted. The style in his letters is, at times, just as symbolic as in his visionary writings, as he comes to provide advice with the same authority and in the name of the divine voice that dictated his visions.

Regarding his hagiographical writings, there is the Vita sancti Disibodi (Life of Saint Disibodo), written around 1170 at the request of Helenger, abbot of the Disibodenberg Monastery, where he deals with the life and work of the Irish hermit Disibodo, who spent his last years in the vicinity of the monastery that he presided over. Around the same time he wrote the Vita sancti Ruperti , in which he documents the life of the patron saint of the monastery founded on the hill where the relics of Rupert of Bingen supposedly rested.

He also wrote an explanation of the rule of Saint Benedict (Explanatio regule s. Benedicti) and another of the Athanasian Symbol (Explanatio symboli s. Athanasii).

Musical works

The prolific nature of Hildegard's musical work allows us to establish the importance that music and singing had for the Rhine sibyl. Such importance was revealed in the letter written to the curia of Mainz, issued after the interdict filed on the occasion of the conflict derived from the abbess burying a man supposedly excommunicated and for which his community was prohibited from singing the psalter. and have mass.

In said letter, after declaring herself willing to obey the measures imposed and based on a quote from Psalm 150, Hildegarda explains that singing is a manifestation of the divine spirit in man, which with it vaguely recalls the blessedness of Adam in the paradise, who participated in the voice and song of the angels in praise of God. The prophets, to whom God bestowed an extraordinary grace, had composed songs and created instruments, glimpsing the beatific past of humanity. In fact, musical instruments, when played with the fingers, reminded Adam himself created by the "finger of God."

Praise to God within the Church has its origin in the Holy Spirit and is in accordance with heavenly harmony:

The body is true dressed in the spirit, which possesses a living voice, that in this way the body with the soul may use its voice to sing the praises of God.Ep. XXIII, PL CXCVII, Migne, 1855.

Although it uses the monophonic technique, the melisma and the notation typical of its time, Hildegard's music is differentiated by the use of wide tonal ranges, which require the singer or the choir to rise to intense treble while being in an intermediate note or low. Contracts melodic phrases that prompt the voice to be faster and then slow down. He also uses fourth and fifth intervals, when the singing of his time rarely went beyond thirds.

All of the musical works of the Teutonic prophetess were created for the liturgical needs of her own community, as well as for theological-moral didactics, in the case of the Ordo Virtutum.

Hildegarde composed seventy-eight musical works, grouped into Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum (Symphonia of the harmony of heavenly revelations): forty-three antiphons, eighteen responsories, four hymns, seven sequences, two symphonies (with the proper meaning of the XII century), one hallelujah, one kyrie, one piece and an oratory (fascinating, as the oratory was invented in the 17th century). In addition, she composed an auto sacramental set to music called Ordo Virtutum (& # 34; Order of the Virtues & # 34;, in Latin), about the virtues.

|

|

|

|

Visions

All the symbolic baggage and originality of Hildegarda's works finds its origin in the supernatural inspiration of her visionary experiences, hence the explanation of said enigmatic source of knowledge has been the cause of interest and research even during the life of the abbess.

Precisely, one of the most important sources on the origin and description of her visions is found in the letter with which Hildegard responded to the epistolary questions made in 1175 by the Flemish Guibert de Gembloux on behalf of the monks of the abbey de Villers, about the way she had her visions. From these answers it is known that her visions began from her very early childhood and that in them she did not mediate sleep, nor ecstasy, nor loss of senses:

I do not hear these things, nor with the bodily ears, nor with the thoughts of my heart, nor do I perceive anything for the encounter of my five senses, but in the soul, with open outer eyes, so that I have never suffered the absence of ecstasy. I see these things awake, both day and night.Hildegarda to the monk Guibert. Ep. CIII.

Similarly, she explains that this supernatural knowledge that she acquires occurs at the same time as having the experience, as she herself writes: "I simultaneously see and hear and know, and almost at the same moment I learn what I know."

Such visions were always accompanied by manifestations of light; in fact, the divine mandates he received came from a luminous theophany which he names "shadow of living light" (umbra viventis lucis) and is this light that he names in the introduction to Scivias and Liber divinorum operum as the one that takes voice to order him to write down what he experiences.

«O little form, [...] entrust these things that you see with the inner eyes and that you perceive with the inner ears of the soul, to the firm writing for the usefulness of men; that men also may understand their creator through it and do not refuse to venerate it with worthy honor.»Introduction to Liber operum divinarum.

This divine light showed him the visions that he describes in his works and that were later illustrated, which have come down to the present thanks to surviving manuscripts, which show a symbolism whose interpretation is not so obvious. He then goes on to explain their deeper meaning and the teachings derived from such visions. Ordinarily these visions were accompanied by physical disorders for the abbess such as weakness, pain and, in some cases, muscle stiffness.

The above has led some scholars to search for neurological, physiological and even psychological causes for the visions, being one of the most widespread medical responses that suffering from a chronic migraine, the latter theory proposed by the historian of medicine Charles Singer and popularized by Oliver Sacks.

Theology

The theological value of Hildegard's teachings has been recognized since ancient times by the Catholic Church in a tradition that continues to the present. Proof of this was the inclusion of her life and her works in the famous historical compilation of theologians published in 1885 by Jacques Paul Migne, the Patrologia Latina , which dedicates its volume CXCVII to this writer. To this is added the modern study and consideration of her, of which the mention of her in public statements and homilies of Benedict XVI is proof of her, as well as the recognition of her as a Doctor of the Church.

Modern interpretations of her writings, such as those made by Barbara Newmann or Sabina Flanagan, have emphasized the feminine character of Hildegard's theology, claiming a gender character to her teachings.

God

The Hildegardian conception of God is not different from the medieval Catholic theological conceptions, nuanced by the peculiarities of their visions. The Trinity, in the book of Scivias, appears as a light in which, in turn, a «most serene light» (splendidissimam lucem) can be distinguished. i>), which represents the Father, a sapphire-colored human figure (spphirini coloris speciem hominis), which symbolizes the Son, and a “softest sparkling fire” (suavissimo rutilantem igne), as a manifestation of the Holy Spirit, images that retain their differentiation by sharing the same unique nature: «in such a way that it was a single light in a single force», « inseparable in His Divine Majesty” and “inviolable without change”.

God is also presented as the source of all strength, life and fertility. In the Liber vite meritorum he is represented as a male (vir) precisely because in him resides the vigor that he communicates to what exists, not only through the act of creation, but even through the immanence of his power that sustains the world, granting fecundity (viriditas) to nature and spirit.

Man and the world

As in the rest of the medieval theological culture, Hildegard considers man as the center of the world created by God and a participant in the redemptive work. According to Liber divinorum operum , man, made in the likeness of God, has a resemblance to another of the great works of the Almighty: the cosmos. This resemblance is reflected even at the body level, since in the body one can distinguish aerial, watery, winter, cloudy, warm parts, etc. Man and cosmos interact and are ordered according to the divine plan. That is why the cosmos can be read as a lesson to teach man to love his creator and keep proper morals. Both one and the other are destined for their final reintegration to God, but man with his free will can choose to rebel.

The moral quality of man has been injured since the fall of Adam and Eve because of sin, however, God chooses that same weakness to grant salvation through his son Jesus Christ, who takes flesh to rescue man, who in turn must tend towards God with his thoughts and actions, choosing virtues over vices.

Christ and the Church

The Word of God, made flesh in the figure of Jesus Christ, thus possesses the double divine and human nature, in the same way that the Church, the sacraments and the virtues possess supernatural and mundane realities.

The Abbess of the Rhine shares the patristic vision of the Church as the new Eve issued from the rib of Christ, guardian of salvation in the world and prefigured in the Virgin Mary. It is opposed to the Synagogue, which represents the enemies of the faith and of God. /i>", crowned and dressed in splendor, with her belly pierced through which a multitude of dark-skinned men enter who are purified as they exit through her mouth.

A common image in Christian theology is not alien to Hildegard's ecclesiology, that of the "betrothal of the Church." The Church, as mystical bride, marries Christ through his passion: «Flooded by the blood that flowed from his side, she was united to him in happy betrothal by the superior will of the Father, and remarkably endowed by his flesh and by his blood”, thus becoming a mediator of the sacraments that update the life of Christ over time.

Hildegarda of Bingen in modern culture

Her figure and her work left their influence felt even outside of Germany and reached the present with indisputable validity, which has led the world of culture to pay various tributes to the German saint.

The parish church of Eibingen, where the relics of this saint rest, was largely rebuilt in 1932 after a fire, after which it was adapted to a more contemporary style by the Rummel brothers. The main altar is adorned by a mosaic that reproduces Hildegard's vision of the Trinity found in Scivias, II, 2; This work was designed in 1965 by the German expressionist Ludwig Baur, who also designed the stained glass windows of the church, which also represent some visions of the abbess.

St. Hildegard's Abbey in Rüdesheim am Rhein is a Benedictine abbey rebuilt between 1900 and 1908 on the original ruins of one of Hildegard's foundations. The reconstruction was ordered by Prince Carl Henry of Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg in a neo-Romanesque style. The main nave of the abbey church is adorned with frescoes depicting visions of the abbess, and in its arches there are others showing scenes from Hildegard's life, painted in the style of the Beuron school of art, by Desiderius Lenz. under the direction of Paulus Krebs. This abbey is part of the Cultural Landscape of the Upper Middle Rhine Valley, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2002.

In the town of Bingen am Rhein, a museum has been dedicated to the life and work of this saint, where contemporary documents of hers are exhibited as well as some remains of the constructions led by the abbess. A first impression from 1533 of her work Physica is also on display, also having an adjoining garden where the plants described in her naturalist works are found.

In cinematography, the film A Beautiful Mind, winner of the Oscar for best film in 2001, used one of Hildegarda's songs titled Columba aspexit within the soundtrack, for which he also received a nomination for said award. In 2009, the German director Margarethe von Trotta filmed the film Vision: The Story of Hildegard von Bingen (Vision. Aus dem Leben der Hildegard von Bingen), based on the life of this saint, played by the German actress Barbara Sukowa. It was released in Spanish on August 27, 2010. In the 2009 Italian film Barbarossa (translated into English as Sword of War), based on the life of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, Hildegarda de Bingen has an appearance, in which she is played by the Spanish actress Ángela Molina.

The figure of Hildegard has also had a certain presence on television: in 1994 the BBC in London produced the documentary Hildegard of Bingen for English television; German television also produced the documentary Hildegard von Bingen - Eine Frau des 12. Jahrhunderts (Hildegard of Bingen. A 12th-century woman) and dedicated a chapter of the series Die Deutschen (The Germans) to this Benedictine nun.

The discography generated from his music is abundant. Since 1979, around thirty-five records have been produced with performances of the religious songs composed by her, highlighting the performances by Gothic Voices, Emma Kirkby, the Oxford Camerata under the direction of Jeremy Summerly, Garmarna and Anonymous 4.

On April 14, 1998, the German government issued a commemorative coin for the 900th anniversary of Hildegard of Bingen's birth. The edition consisted of a total of 4.5 million 10-mark coins, made of 925 thousandth sterling silver, where the effigy of the saint can be seen writing the divine messages together with a band that reads Liber Scivias Domini and the years of his birth and death.

In astronomy, the asteroid (898) Hildegard, discovered by German astronomer Max Wolf on August 3, 1918, is named after this German mystic.

Similarly, the modern consideration of the relevance of the figure of Hildegard in the Middle Ages as well as for the history of the Church, has led ecclesiastical and secular feminist groups to take her as a relevant example of claiming the role of women in history and its importance in opening up traditionally masculine roles to the feminine gender.

Also, musician Devendra Banhart paid homage to this Saint in his video Für Hildegard von Bingen, which was released in October 2013, showcasing Hildegard's artistic side.

Cuban writer Daína Chaviano dedicated her novel El hombre, la hembra y el hambre (Azorín Novel Award 1998) to this nun, whose figure plays a fundamental role in the plot. Although the novel revolves around a Cuban jinetera or prostitute, this character's interaction with a friendly nun serves as the basis for commenting on Hildegarda's mystical life and her musical contributions.

On the other hand, the lunar crater Hildegard has been named after her since February 2016.

Image gallery

Of his works

Frescoes in St. Hildegard's Abbey in Rüdesheim am Rhein

Contenido relacionado

Harvard Medical School

Eisenach

History of iraq