Heraldry

The heraldry comes from the masculine name herald, that is, the one who announced and described the knights entering the tournament, the one who announced the facts, the one who led declarations of war as a public official in the Middle Ages. In addition to being an adjective, heraldry is a noun that denotes the science that helps us understand and properly compose coats of arms, or the code of rules that allows us to correctly represent and describe coats of arms.

Strictly defined, it denotes what belongs to the office and duty of a herald, whose visible head was the king of arms; that part of his work dealing with coats of arms is properly called armory, but in general usage heraldry has come to mean the same thing as armory. a discipline related to the design, display, and study of coats of arms, as well as related disciplines, the study of ceremony, rank, and pedigree

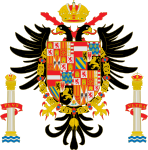

The branch of armory refers to the design and transmission of heraldic achievement. This includes a coat of arms, helmet, and crest, along with any accompanying ornaments and items, such as supports (or tenant), heraldic banners, mottos, or war cry.

Origin

The heraldry was developed during the Middle Ages throughout Europe until it became a coherent code of identification of persons, progressively incorporated by estates of feudal society such as the nobility and the Catholic Church for genealogical identification (and where the coat of arms can be transmitted by inheritance, translating the degree of kinship) and members of the hierarchy, being equally adopted by other human groups, such as guilds and associations, in addition to being adopted for the identification of cities, towns and territories.

It was also a unique emblematic system at a time when recognition and identification rarely happened through a written document. Appearing in the XII century, aimed at male members of the aristocracy, it quickly spread throughout Western society: women, clergy, villagers, bourgeois and communities. Consequently, they have also served to represent cities, regions, countries and professional groups.

Stages of heraldry

Ancient heraldry

The earliest depictions of different peoples and regions in Egyptian art show the use of banners topped with the images or symbols of various gods. The kings' names appear on emblems known as serekhs, which represent the king's palace. They are generally crowned with a falcon that represents the god Horus. Similar emblems and representations are found in ancient Mesopotamian art from the same period, and the forerunners of heraldic beasts such as the griffin can also be found.

Greek and Latin writers frequently describe the shields and symbols of various heroes, and units of the Roman army were sometimes identified with distinctive markings on their shields (see Notitia dignitatum ).

Until the 19th century it was common for heraldic writers to cite examples such as these and metaphorical symbols such as the Lion of Judah or the Eagle of the Caesars, as evidence of the antiquity of heraldry itself, and infer from this that the great figures of ancient history carried weapons that represented their noble status and ancestry. The Book of St Albans, compiled in 1486, states that Christ himself was a knight in armor. These claims are now regarded as the fantasy of medieval heralds, as there is no evidence of a distinctive symbolic language similar to that of heraldry. during this early period; not many of the shields described in antiquity are very similar to those of medieval heraldry; there is also no evidence that specific symbols or designs were passed down from one generation to the next, representing a particular person or line of descent.

Medieval heralds also attributed weapons to various knights and lords throughout history and literature. Notable examples include the toads attributed to Pharamond, Edward the Confessor's cross and mertle, and the various weapons attributed to the Nine of Fame and the Knights of the Round Table. These too are easily dismissed as fanciful inventions, rather than evidence of the antiquity of heraldry.

Modern heraldry

The use of heraldic emblems began in Western Europe, specifically in the English Channel area, as a sign to identify the knights and leaders of the hosts on the battlefields —usually hidden in their helmets and armor—and it spread immediately throughout the continent, adapting to the peculiar circumstances of the different cultures it encountered in its path.

The development of the modern heraldic language cannot be attributed to a single individual, time, or place. Although certain designs now considered heraldic were evidently in use during the 11th century, most accounts and depictions of shields up to the early 12th century contain little or no evidence of their heraldic character. For example, the Bayeux Tapestry, illustrating the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, and probably commissioned around 1077, when Bayeux Cathedral was rebuilt, depicts a series of shields of various shapes and designs, many of which are simple., while others are decorated with dragons, crosses or other typically heraldic figures. However, no individual is depicted twice with the same arms, nor are the descendants of the various people depicted to the handed down devices resembling those on the tapestry.

Similarly, an account of French knights at the court of Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos in the early 12th century describes their polished metal shields, devoid of heraldic design. A Spanish manuscript of 1109 describes simple and decorated shields, neither of which appears to have been heraldic.

The Basilica of Saint-Denis contained a window commemorating the knights who embarked on the Second Crusade in 1147, and was probably made shortly after the event; but Montfaucon's illustration of the window before it was destroyed shows no heraldic design on any of the shields.

In England, from the time of the Norman Conquest, official documents had to be sealed. From the XII century, the seals assumed a clearly heraldic character; several seals dating between 1135 and 1155 appear to show the adoption of heraldic devices in England, France, Germany, Spain, and Italy.

A notable example of an early armor seal is attached to a charter granted by Philip of Alsace, in 1164. Seals from the latter part of the century XI and early XII show no evidence of heraldic symbolism, but by the late XII, the seals are uniformly heraldic in nature.

Heraldic Achievement

| Generic weapons shielding with the highest number of external supports and ornaments in heraldic |

A heraldic achievement consists of a coat of arms, stamp, brackets, motto and/or war cry, and other heraldic exterior ornaments.

More elaborate achievements sometimes display the full coat of arms under a canopy, ornate tent, or canopy of the type associated with medieval tournament, though this is only very rarely found on English achievements or arms or Scottish

Elements inside the shield

The term coat of arms technically refers to the shield or blazon itself, but the phrase is commonly used to refer to all achievement >. The only indispensable element of a coat of arms is the escudo. Many of them, the oldest, do not consist of anything else, but there is no achievement or armor without a coat of arms.

The main elements of a shield/blazon are:

- Heraldic partition: La partition It's the division in various geometric zones of a field, a figure or an element of a previous partition.

- Headquarters: Each of the blazons or divisions of which is composed a shield in general.

- Composite weapons: It's a meeting of several shields on one.

- Geometric attribute

- Field: The field is what is within the Shield, which has various parts or variations.

- Enamels (Colors, Metals and Forros): It is called enamel from the shield to any of the colors, metals or linings of it. Enamels and metals, being represented in black and white or on engravings, are subject to conventions to distinguish them.

- Field composition: It is the repetition and filling of the shield field.

- Seed: Representation of identical elements, usually figures, within the shield field, or of the field of certain elements, on whose edges only the halves of the repeated elements are represented.

- Heraldic figures: The figure is all that is put on ornate stew over a raso shield.

- Location of the heraldic figures Heraldic pieces: The pieces are geometrical charges or figures, limited to the stroke by geometric lines that separate them from the field.

- List of Heraldic Furniture Parts: Furnitures are figures that are placed on the shield and which is not a piece or part thereof, it is what adorns, loads or accompanies the field or division of a shield.

- List of furniture

Elements within the timbre

From a very early date, illustrations of weapons were often adorned with Helms placed on top of shields. These in turn came to be decorated with sculptural or fan-shaped crests, often incorporating elements of the coat of arms; as well as a crown or Burelete, or sometimes a small crown (coroneta), on which the Lambrequin depended.

- Cimera. The chimera rests on a Yelmo which in turn rests on the most important part of achievement: the shield.

- Yelmo

- Crown

- Burelete

- Lambrequin

Motto and rallying cry

- The slogan armor is a phrase or collection of words intended to describe the motivation or intent of the person or entity, which is shown in a tape, usually under the shield.

- The War scream is a simple word or phrase, to encourage you to join the struggle or action, to your members or followers that is placed on a slate on the shield.

Tenante, support, support and exterior ornaments

The tenants are human, animal, or architectural figures that accompany each side of the coat of arms with the action of support. Those that are made up of animal figures (real or imaginary) are called supports, while the figures of vegetables and inanimate objects are called supports.

Historical examples

Contenido relacionado

Parthenon

Dadaism

Osamu tezuka

![Ejemplo de armorial del rey Enrique III y sus principales nobles, en el Libro de las adiciones de Matthew Paris, de 1259.[16]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/MatthewParis_BookOfAdditions_BritishLibrary.jpg/104px-MatthewParis_BookOfAdditions_BritishLibrary.jpg)