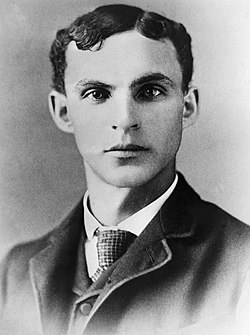

Henry ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863, Dearborn, Michigan - Ib., April 7, 1947) was an American businessman and entrepreneur, founder of the company Ford Motor Company and father of modern production lines used for mass production. At the same time he was an extremely racist, anti-Semitic and white supremacist person. His ideas, in this regard, greatly inspired Nazism and Adolf Hitler, who was a fanatical admirer of the ideas of racial hatred expressed by Henry Ford.

The introduction of the Model T to the automobile market revolutionized transportation and industry in the United States. He was a prolific inventor who obtained 161 registered patents in this country. As the sole owner of the Ford company, he became one of the best known and richest people in the world.

He is credited with Fordism, a system that spread between the late 1930s and early 1970s, which he created by manufacturing large numbers of low-cost automobiles through mass production. This system entailed the use of specialized machinery and a large number of workers on staff with high salaries.

His global vision, with consumerism as the key to peace, is the key to his success. His intense commitment to cost reduction led to a host of business and technical inventions, including a franchise system that established a dealership in every city in the United States and Canada and in major cities on five continents.

Ford left much of his vast fortune to the Ford Foundation, but he also made sure that his family controlled the company permanently.

Early Years

Henry Ford was born on a farm to a very poor family in a rural town west of Detroit (the area in question is now part of Dearborn, Michigan). His parents were William Ford (1826-1905) and Mary Litogot (c. 1839-1876). They were of English descent, but had lived in Ireland, in County Cork. He had several siblings: Margaret (1867-1868), Jane (c. 1868-1945), William (1871-1917), and Robert (1873-1934).

During the summer of 1873, Henry first saw a self-propelled machine; a stationary steam engine that could be used for agricultural activities. The operator, Fred Reden, had mounted it on top of wheels to which he had attached a chain. Henry became fascinated with the machine, and Reden over the next year taught the young man how to start and operate the engine. Ford later said that it was this experience that "taught him that he was by instinct an engineer."

Henry brought this passion for engines into his own home. His father gave him a wristwatch in his early teens. At 15 he had a good reputation as a watch repairman, having dismantled and reassembled the watches of friends and neighbors dozens of times.

His mother died in 1876. It was a heavy blow that left the young man devastated. His father hoped that Henry would eventually take over the family farm, but Henry hated that job. On the other hand, with his mother dead, there was little to tie him to the farm. He later said, "I never had a particular love for the farm. She was the mother on the farm that he loved."

In 1879 he left home for Detroit to work as a machinist's apprentice, first at James F. Flower & Bros., and later the Detroit Dry Dock Co. In 1882 he returned to Dearborn to work on the farm, operating the Westinghouse portable steam engine until he became an expert. This led to his being hired by the Westinghouse Company to service their steam engines.

During his marriage to Clara Bryant in 1888, Ford supported himself by farming and operating a sawmill. They had a son, Edsel Bryant Ford (1893-1943).

In 1891, Ford got a job as an engineer at the Edison Company, and after his promotion to chief engineer in 1893 he began to have enough time and money to devote to his own experiments with gasoline engines. These experiments culminated in 1896 with the invention of his own self-propelled vehicle called the quadricycle, which made its first successful test run on June 4 of that year. After several tests, Ford began to develop ideas to improve it.

Detroit Automobile Company and the Henry Ford Company

Following this successful start, Ford joined Edison Illuminating in 1899 along with other inventors, and they formed the Detroit Automobile Company. The company soon went bankrupt because Ford continued to improve prototypes instead of selling cars. He would race his own car against those of other manufacturers to demonstrate the superiority of his design. With this interest in racing cars he created the Henry Ford Company. During this period he personally drove one of his cars in victory over Alexander Winton on October 10, 1901.

In 1902, Ford continued to work on his racing car, to the detriment of his investors. They wanted a model ready for sale and brought in Henry M. Leland to carry it out. Ford resigned in the face of this infringement of his authority, later saying, I resigned determined never to place myself under anyone's orders again. The company was reorganized under the new name of Cadillac.

Ford Motor Company

Henry Ford only succeeded in his third business venture, launched in 1903: the Ford Motor Company, founded on June 16 with 11 other investors and an initial investment of US$28,000. In a newly designed car, Ford put on a display in which the car ran the mile distance on frozen Lake St. Clair in 39.4 seconds, breaking the land speed record. Convinced by this success, the famous race car driver Barney Oldfield, who named this model Ford 999 after one of the racing cars of the time, drove the car across the country, making the new brand Ford was known throughout the US Ford was also an early promoter of the Indianapolis 500.

Ford stunned the world in 1914 by offering its workers wages of $5 a day, which at the time was more than double what most such employees were paid. This tactic paid off immensely when Detroit's top mechanics began switching to Ford, bringing their human capital and experience with them, increasing productivity and lowering training costs. Ford called it "wage motivation." The company's use of vertical integration also came in handy, when Ford built a gigantic factory where raw materials went in and finished cars went out.

The "T" Model

The T-Ford appeared on the market on October 1, 1908 and featured a host of innovations. For example, it was left-hand drive, something that the vast majority of other companies soon copied. The entire engine and transmission were enclosed, all four cylinders were housed in a solid block, and the suspension was powered by two semi-elliptic springs. The car was very easy to drive and, more importantly, very cheap and easy to repair. It was so cheap that, costing US$825 in 1908 (the price dropped every year), by 1920 the vast majority of drivers had learned to drive in the Model T Ford.

Ford also took care to install massive advertising in Detroit, making sure that stories and advertisements about their new product appeared in every newspaper. Their local dealership system made the car available in every city in the US. For their part, the dealers (independent businessmen) were getting richer and helped to publicize the very idea of motoring, beginning to develop automobile clubs to help drivers and to go beyond the city. Ford was delighted to sell to farmers, who saw the vehicle as just another invention to help them with their work.

Sales skyrocketed. For several years the records of the previous year were being broken. Sales exceeded 250,000 vehicles in 1914. For its part, always on the lookout for cost reduction and greater efficiency, Ford introduced moving assembly belts to its plants in 1913, which allowed for an enormous increase in production.

While Ford is often credited for this idea, contemporary sources indicate that the concept and its development began with employees Clarence Avery, Peter E. Martin, Charles E. Sorensen, and C. H. Wills. By 1916 the price had fallen to $360 for the basic car, with sales reaching $472,000. At the same time, Ford is mistakenly credited with being the first to apply the concept of line production. assembly, when in fact Ransom Eli Olds was the first to apply it in the year 1900, to produce his Oldsmobile Curved Dash model. Despite this, Ford went down in history for having perfected that system, achieving a larger-scale production range than with the system applied by Olds.

By 1918 half the cars in the US were Ford Model Ts.[citation needed] Ford wrote in his autobiography that "any customer can have the color car you want as long as it's black." Until the assembly line application, in which the color used was black because it had a shorter drying time, there were Ford Ts in other colors, including red. The design was fervently promoted and defended by Henry Ford, and production continued until the end of 1927. Final total production was 15,007,034 units, a record that stood for the next 45 years.

In 1918 US President Woodrow Wilson personally asked Henry Ford to run for the Michigan State Senate as a representative of the Democratic Party.

Although the nation was at war, Ford was a political pacifist and supporter of the League of Nations. In December 1918 Henry Ford passed the company presidency from him to his son, Edsel Ford.

Henry, however, maintained his authority over the final decisions and occasionally modified some of his son's decisions. Henry and Edsel bought out all the remaining shares from the other investors, bringing the company outright ownership to the family.

The Model A and Ford's late career

In 1926, the drop in sales of the T-Ford finally convinced Henry that it was convenient to create a new model of automobile. Henry embarked on the project focusing on the design of the engine, chassis and other mechanical needs, while leaving the design of the body of the car to his son. Edsel also managed to overcome some of his father's initial objections and include some technical designs such as the gearbox. The result was the Ford A, which appeared in December 1927 and was built until 1931 with a total production of about four million cars. The company adopted a model of annual product modifications similar to what is done today.

The Death of Edsel Ford

In May 1943 Edsel Ford died of stomach cancer, vacating the presidency of the company. Henry Ford championed Harry Bennett, his partner of many years, to take that position. For her part, Edsel's widow, Eleanor, who had inherited Edsel's voting rights, wanted her son Henry Ford II to take over the company. The issue was settled for a time when Henry, at the age of 79, took over the presidency personally. Henry Ford II was released from his navy duties and became executive vice-president, while Harry Bennett took a position on the board as head of personnel, labor relations and public relations. The company hit a rocky patch over the next two years, losing $10 million a month. By 1945 Henry Ford's senility was already evident, and his wife and his daughter-in-law forced his resignation in favor of his grandson, Henry Ford II.

Ford's work philosophy

Henry Ford was a pioneer of the welfare state through the consumer society. He sought to improve the standard of living of his workers and reduce their turnover. Efficiency meant hiring and keeping the best workers. On January 5, 1914, Ford announced his $5-a-day compensation program. This revolutionary program also included the reduction of the working day from 9 to 8 hours a day, 5 days a week, as well as the aforementioned increase from $2.34 a day to 5 for skilled workers.

Ford was criticized by Wall Street for beginning the implementation of the 40-hour week and for establishing a minimum wage. However, he showed that such a payment allowed his workers to buy the same cars they produced, and was therefore good for the economy. Ford called this increase in wages a form of profit sharing. The $5 salary was offered to men over the age of 22 who had worked at the company for six months or more and, more importantly, led a life that was approved by the "Sociology Department." They did not approve of excessive drinking or gambling. The department used 150 investigators and supported bosses to uphold employee standards. A large percentage of employees managed to qualify to receive this part of the benefits.

Ford was completely against unions in its factories. To stop this type of activity he promoted Harry Bennett, a former Navy boxer, to head the Service Department. Bennet used various intimidation tactics to crack down on union organizing. The most famous incident, in 1937, was a bloody fight between the security forces and trade unionists in front of the media.

Ford Aviation Company

Ford, like other car companies, entered the aviation business during World War I, building Liberty engines. After the war it returned to its own manufacturing until 1925, when Henry Ford acquired the Stout Metal Airplane Company.

Ford's most successful aircraft was the Trimotor, commonly called the Tin Goose. It used a new alloy called Alclad that combined the corrosion resistance of aluminum with the hardness of duralumin. The aircraft was similar to the Fokker V.VII-3m, and some say[who?] that Ford engineers measured the aircraft and then copied it. The Trimotor first flew on June 11, 1926 and was the first successful airliner, seating about 12 passengers fairly comfortably. There were several variants that were used by the army. In total about 200 of these devices were built until the company closed due to the fall in sales caused by the Depression.

Ford's Tin Goose Trimotor is considered to be the forerunner of the current Fokker 50, Dash 7+, ATR 72, Antonov 24, Avro-HS748, etc. These planes were international aviation successes and tri-engines still exist in flight in some places.

Messenger of Peace

In 1915 he financed a trip to Europe, where World War I was taking place, for himself and 170 other peace leaders. He spoke to President Wilson about the trip, but received no government support. The group headed to neutral Switzerland and the Netherlands to meet with peace activists. Ford, the object of much ridicule, left the mission as soon as he arrived in Switzerland.

An article written by British writer G. K. Chesterton on December 11, 1915 for the Illustrated London News shows why his efforts are being mocked. Referring to Ford as "the American comedian", Chesterton notes that Ford had gone so far as to say that "I think the sinking of the Lusitania was deliberately engineered to get this country, the USA, into the war. It was planned by those who finance the war. Chesterton expressed his "difficulty in believing that bankers would swim under the sea to cut holes in the bottoms of ships", and asked why, if what Ford said was true, Germany had accepted responsibility for the sinking and "defended what that I hadn't done." According to him, Ford's efforts posed a problem for "more plausible and presentable" pacifists.

On the Other Side H. G. Wells, in his science fiction novel The Shape of Things to Come, devoted an entire chapter to to Ford's peace ship, stating that "even though he was unsuccessful, his effort to stop the war will be remembered while the generals and their battles and senseless massacres will be forgotten." Wells accused the US arms industry and banks—which made huge profits selling munitions to warring European nations—of having spread lies, in order to cause Ford to fail in his peace efforts. However, he pointed out that when the US entered the war in 1917, Ford himself made considerable profits from munitions sales.

Anti-Semitism

In 1918, one of Ford's closest associates and personal secretary, Ernest G. Liebold, bought a weekly newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, so that Ford could publish his views. By 1920 Ford had become an anti-Semite and in March of that year he began an anti-Jewish crusade in the pages of his newspaper. The newspaper continued to function for eight years, from 1920 to 1927, during which time Liebold was the editor. The newspaper published The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which was later discredited by an investigation by The Times of London. The Jewish Historical Society of America describes the ideas that appeared in the newspaper as anti-immigration, anti-unionism, anti-alcohol and anti-Jews. In February 1921 the newspaper New York World published an interview with Ford in which he said that «The only comment I will say about the Protocols is that they fit what is happening ». During this period Ford emerged as "a respected spokesman for far-right and religious prejudice" eventually commanding around 700,000 readers of his newspaper.

Along with the Protocols other anti-Semitic articles were published in The Dearborn Independent. A four-volume compilation called The International Jew, the World's Foremost Problem was published in the 1920s. Vincent Curcio writes of these publications that "they were very widely distributed and had great influence, particularly in Nazi Germany, where none other than Adolf Hitler read and admired them. Hitler hung Ford's photo on the wall, and based several sections of Mein Kampf on his writing: what's more, Ford is the only American mentioned in his book. According to Lacey "no American contributed as much to Nazism as Henry Ford". Steven Watts wrote that Hitler "revered" Ford, proclaiming that "I will do what I can to put his theories into practice in Germany", and modeling the Volkswagen, the people's car, after the Ford T". In Mein Kampf (written in the mid-1920s) Hitler expressed his opinion that, “It is the Jews who rule the forces of the Stock Market in the American Union. Every year he turns them more and more into the masters who control the producers of a nation of 120 million. But to their fury, only one man, Ford, still maintains complete independence."

It was denounced by the Anti-Defamation League (a Jewish organization founded and directed by the B'nai B'rith), although the articles explicitly condemned violence against Jews (Volume 4, chapter 80), although they preferred to blame the Jews for causing the episodes of violence. However, these articles were not actually written by Ford, who wrote virtually nothing according to his testimony at trial. Friends and business associates of his said they warned him about the contents of the Independent and that Ford would probably never read it (he claimed he only read the headlines). In any case, one of the witnesses in the trial brought by one of the newspaper's targets claimed that Ford did know the contents of the Independent prior to its publication.

A lawsuit by Aaron Sapiro (a Jewish San Francisco lawyer who organized a cooperative farm), in response to the magazine's anti-Semitic comments, led to Ford closing the Independent in December 1927. The news then said that he had been surprised by the content and did not know its nature. During the trial, the editor of Ford's "own page", William Cameron, testified that Ford had nothing to do with the editorials even though they were even under his byline. He also testified that he had never discussed its content or asked for Ford's approval. On the other hand, investigative journalist Max Wallace said that whatever credibility this absurd claim might have had was soon undermined when James M. Miller, a former employee of the newspaper, said under oath that Ford had told him he intended to go for Sapiro.

Michael Barkun observed that Cameron would have continued to publish such controversial material without Ford's explicit instructions seemed unthinkable to those who knew both. Mrs. Stanley Ruddiman, an intimate of Ford's family, remarked that she "did not believe Cameron would write anything for the publication without Ford's approval". According to Spencer Blakesle

The Anti-Defamation League mobilized prominent Jews and non-Jews to publicly oppose Ford's message. They formed a coalition of Hebrew groups for the same purpose, and made constant complaints in the Detroit press. Before leaving the presidency early in 1921, Woodrow Wilson joined other U.S. leaders in an assertion that challenged Ford and others for their anti-Semitic campaign. A boycott against Ford's products by liberal Jews and Christians also had its impact, and Ford closed the paper in 1927, putting his vision in an open letter to Sigmund Livingston of the Anti-Defamation League.

Ford later became associated with the notorious anti-Semite Gerald L.K. Smith, who commented after their meeting in the 1930s that he was "less anti-Semitic than Ford." Smith also stressed that in 1940 Ford showed no remorse for the anti-Semitic views of the Independent and "hoped to publish The International Jew again later". Later that year Ford commented in The Guardian that "Jewish international bankers" were responsible for World War II.

In 1938 the German consul in Cleveland awarded Ford the Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle, the highest decoration Nazi Germany could award to a foreigner.

Distribution of International Jew was discontinued in 1942, although extremist groups often recycle the material, which still appears in anti-Semitic and neo-Nazi information and websites.

Ford's business worldwide

Ford's philosophy of international economics was one of economic independence from the United States. Its Rouge River plant in Michigan would become the largest industrial complex in the world, even capable of producing its own steel. Ford's goal was to produce a vehicle from scratch without relying on foreign trade. He believed that international trade and cooperation lead to international peace and used the Model T production line to demonstrate this.

It opened production plants in the United Kingdom and Canada in 1911 and soon became the largest producer of automobiles in those countries. In 1912 Ford cooperated with Fiat's Agnelli to launch the first Italian production lines. The first plants in Germany were built in the 1920s with the support of Herbert Hoover and the Department of Commerce, who agreed with Ford's theory that international trade was essential to world peace.

During the 1920s Ford also opened plants in Australia, India and France and by 1929 had dealers on five continents. Ford experimented with a commercial rubber plantation in the Amazon jungle called Fordlândia which was one of his few failures. In 1929 he accepted Stalin's invitation to build a model plant (NNAZ, today called GAZ) in Gorki, a city later renamed Nizhny Novgorod, and sent American engineers and technicians to help run it, including the future union leader. Walter Reuther.

Technical assistance agreement between Ford Motor Company, VSNH, and Amtorg (as purchaser) concluded at 9 years and was extended on May 31, 1929 signed by Ford, Vice President Peter E. Martin, V. I Mezhlauk, and Amtorg Chairman Saul G. Bron. With whichever nation the US had peaceful diplomatic relations with, the Ford Motor Company would do business. By 1932, Ford was producing a third of all world automobile production.

Ford's image transfigured Europeans, especially Germans, provoking "fear for some, romantic vision for others and fascination for all". Germans who discussed Fordism often believed that it represented something quintessentially American. They saw size, time, standardization, and the philosophy of production as demonstrating that Ford worked as a national service: an "American thing." » that represented US culture. Supporters and critics alike insisted that Fordism was the epitome of capitalist development, and that the automobile industry was the key to understanding economic and social relations in the United States. One German explained that "automobiles have changed so much the American way of life that today one can hardly imagine being without a car. It is difficult to remember what life was like before Mr. Ford began to preach his doctrine of salvation ». For many Germans, Henry Ford embodied the essence of the American dream.

The races

Ford began his career as a racing driver and maintained his interest in racing. From 1909 to 1913, Ford took the Model T to racing, finishing first (though later disqualified) in a cross-country race in 1909, and setting the one-mile speed record at Detroit in 1911 with the driver Frank Kulick. In 1913, Ford tried to put a new Model T in the Indianapolis 500, but was told that regulations required about 1,000 pounds of weight to be added to the car to enter the race. Ford withdrew from the race and soon left racing permanently, citing dissatisfaction with the rules of the sport and the demands of the time.

The Ford Foundation

Henry Ford and his son, Edsel, founded the Ford Foundation in 1936 with the broad objective of promoting the welfare of the people. Ford divided his capital into a small number of voting shares, which he divided among his family, and a large number of non-voting shares, which he gave to the Foundation. The Foundation grew immensely and, by 1950, it already had an international scope. He gradually sold all his shares on the market from 1955 to 1974, and lost his connection to the Ford Motor Company and the Ford family.

Death

When Edsel Ford, president of the Ford Motor Company, died of cancer in May 1943, the elderly and ailing Henry Ford decided to assume the presidency. At this point, Ford, who was in his late 80s, had had several cardiovascular events (cited as heart attacks or strokes), and was mentally inconsistent, suspicious, and generally unfit for such immense responsibilities.

Most of the directors didn't want to see him as president. But for the past 20 years, though he had been without any official executive title, he had always had de facto control over the company; he had never been seriously challenged by the board and management, and this moment was no different. The directors chose him and he served until the end of the war. During this period, the company began to decline, losing more than $10 million a month ($147,750,000 today). President Franklin Roosevelt's administration had been considering a government takeover of the company to ensure continued war production, but the idea never progressed.

As his health failed, Ford turned over the company presidency to his grandson, Henry Ford II, in September 1945 and retired. He died on April 7, 1947, of a brain hemorrhage on Fair Lane, his Dearborn estate, at the age of 83. He was given a public viewing in Greenfield Village, where up to 5,000 people an hour passed the coffin. Funeral services were held at Detroit's Cathedral Church of St. Paul and he was interred at Ford Cemetery in Detroit.

Appearances in artistic works

- It is mentioned in the book of Aldous Huxley: A happy world

- It is mentioned in the book of Yevgueni Zamiatin: We

- It's one of the characters in the documentary series. Gigantes de la Industria

- In Assassin's Creed II it is mentioned that he was the leader of the Temporary Order and one of the founders of Abstergo Industries.

- Philip Roth's "The Conjure Against America" dystopia is part of Hitler's fascist government partner.

Works

- The Case Against the Little White Slaver ("The Case Against the Small White Slave"), 1914

- The Jewish question: a selection of articles (1920-1922) published by the weekly The Dearborn Independent and reprints later under the general title The International Jewish

- The International Jew: The First Problem of the World, 1920

- My life and work ("My Life and Work"), Garden City, NY, Doubleday, Page & Company, 1922

- Today and Tomorrow ("Today and Tomorrow") together with Samuel Crowther, 1926

- My Philosophy of Industry ("My Industry Philosophy") together with Ray Leone Faurote, 1929

- Edison As I Know Him ("Edison as I know him"), together with Samuel Crowther, 1930

Contenido relacionado

Portuguese economy

Nihonshoki

Paleolithic