Heinz guderian

Heinz Wilhelm Guderian (Chełmno, German Empire, June 17, 1888 - Schwangau, West Germany, May 14, 1954) was a German soldier, colonel general (generaloberst) of the Wehrmacht and Chief of the General Staff of the Army High Command (OKH), after the war, became a successful memoirist. A pioneer and advocate of the concept of modern blitzkrieg (lightning warfare), he played a central role in the development of the Panzer Division concept. In 1943 he became inspector general of the Armored Troops.

At the start of World War II he led an armored corps in the invasion of Poland. During the invasion of France he commanded armored units that charged through the Ardennes forest and overwhelmed the Allied defenses at the Battle of Sedan. He led the 2nd Panzergruppe during Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. The campaign ended in defeat after Operation Typhoon failed in its main objective of capturing Moscow, after this failure and for disobeying Hitler's orders not to back down he was dismissed.

In early 1943 Adolf Hitler appointed him to the newly created position of Inspector General of Armored Troops. In this role he had broad responsibility for rebuilding and training new armored forces, but he had limited success due to Germany's deteriorating war economy. Guderian was appointed chief of the General Staff of the Army High Command, immediately after the attempt on July 20, 1944 to assassinate Hitler and from that moment on, he became Hitler's personal adviser for the eastern front, at which time he closely associated with the Nazi regime.

Guderian was placed in charge of the "Army Court of Honor" by Hitler which, in the aftermath of the plot, was used to expel suspected conspirators from the army so they could be tried at the Volksgerichtshof (people's court) and executed. During Operation Barbarossa the troops under his command carried out the Order of the Commissars and the Barbarossa Decree and he was implicated in committing reprisals after the failed Warsaw uprising of 1944.

He surrendered to US troops on May 10, 1945, and was interned in a prison camp in England until 1948, when he was released without charge and retired to write his memoirs, Memories of a Soldier (German: Erinnerungen eines Soldaten), published in 1950, which quickly became a bestseller, widely read to this day. In his memoirs, he promoted several widespread postwar myths, including the myth of the innocent Wehrmacht and further described himself as the sole creator of the German panzer force; he omitted any mention of his relationship with Hitler and the Nazi regime or of the war crimes committed by troops under his command during the invasion of Poland and the Soviet Union. He died in 1954 and was buried in Goslar.

Biography

Childhood and youth

Heinz Guderian was born on June 17, 1888 in Kulm at the time in West Prussia part of the German Empire (present-day Chełmno, Poland), the son of Friedrich and Clara (née Kirchhoff). His father and grandparents were Prussian officers and he grew up in garrison towns surrounded by the military. In 1903 he left home and enrolled in a military college as a cadet. He was a capable student, though he did poorly on his final exam. He entered the army as an officer candidate in February 1907 with the 10th Battalion, Hanover Light Infantry, under his father's command. He became a second lieutenant in January 1908. On October 1, 1913 he married Margarete Goerne with whom he had two sons, Heinz Günther (1914-2004) and Kurt Bernhard (1918-1984).

At the outbreak of World War I, he served as a communications officer and commander of a radio station. In November 1914 he was promoted to first lieutenant. Between May 1915 and January 1916 he was in charge of signals intelligence for the 4th Army. He fought in the Battle of Verdun during this period and was promoted to captain on 15 November 1915, then posted to the 4th Infantry Division before becoming commander of the 14th Regiment's 2nd Infantry Battalion. On February 28, 1918, he was appointed member of the General Staff of the Army Intelligence Corps, where he specialized in telecommunications. At the end of the war he was assigned as an operations officer in occupied Italy. Despite the dramatic situation in which both the German army and Germany itself were located, he did not agree with that country signing the Armistice of November 11, 1918, because he believed that the German Empire should continue the war.

Prewar

In early 1919 he was selected as one of the four thousand officers allowed by the Versailles Treaty to the Reichswehr restricted to 100,000 men. He was assigned to serve on the staff of the central command of the Eastern Border Guard Service, which was intended to control and coordinate independent freikorps units in the defense of Germany's eastern borders against German forces. Polish and Soviet forces engaged in the Russian Civil War. In June 1919 he joined the Iron Brigade (later known as the Iron Division) as its second staff officer.

In the 1920s he was introduced to armored warfare tactics by Ernst Volckheim, a World War I tank commander and prolific writer on the subject. He studied leading European experts on armored warfare and between 1922 and 1928 he wrote five articles for "Military Weekly", a magazine of the armed forces. Although the topics covered in these articles were mundane, he related them to the theme "Germany has lost World War I", a highly controversial issue at the time and thus raised his profile within the military. Some test tank maneuvers were carried out in the Soviet Union, of which Guderian was in charge of academically evaluating the results. At this time Britain was also experimenting with armored units under General Percy Hobart and kept abreast of Hobart's writings.In 1924 he was appointed instructor and military historian at Stettin (present-day Szczecin).

In 1927 he was promoted to major and in October assigned to the transport section of the Truppenamt, a clandestine form of Army General Staff, which had been expressly prohibited by the Treaty of Versailles. By the fall of 1928 he was a leading speaker and writer on tank-related topics; However, he did not set foot in one until the summer of 1929 when he briefly drove a Swedish Stridsvagn m/21-29 tank. In October 1928 he was transferred to the Motorized Transport Instruction Staff to dedicate himself mainly to teaching tasks. In 1931 he was promoted to Oberstleutnant and became chief of staff of the Inspectorate of Motorized Troops under the command of Generalmajor Oswald Lutz. This placed Guderian at the center of the development of mobile warfare and armored forces in Germany.

In the 1930s he played an important role in the development of both the Panzer Division concept and a mechanized offensive warfare doctrine later known as blitzkrieg. Guderian's 3rder motor transport battalion became the model for the future force German armored However, his role was less central than he later claimed in his memoirs and what many Western historians repeated in the postwar period. He and his immediate superior Lutz had a symbiotic relationship, both working tirelessly with the shared goal of creating a powerful panzer force. Guderian was the public face advocating mechanized warfare, and Lutz worked behind the scenes in the background.

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, he approached the Nazi regime to promote the concept of the panzer force, attract support, and secure the necessary resources for its development. In early 1934, he demonstrated the concept of warfare. armored to Hitler himself, when he saw the experimental tanks available to Germany at that time in operation he exclaimed: "That's what I need! That's what I want to have!" Guderian's vision of blitzkrieg seemed guaranteed.

Lutz cajoled, cajoled, and compensated for Guderian's often arrogant and argumentative behavior toward his peers. In this regard, Italian historian Pier Battistelli wrote that it is difficult to determine exactly who developed each of the ideas behind the panzer force. Many other officers, such as Walther Nehring and Hermann Breith, were also involved in its conception. However, Guderian is widely accepted as a pioneer in the development of the communications system for panzer units. However, the central principles of blitzkrieg – independence, mass and surprise – were first published in mechanized warfare doctrinal statements by Lutz.

During the fall of 1936 Lutz asked Guderian to write Achtung-Panzer! He requested a polemical tone promoting Mobile Troop Command and strategic mechanized warfare. In the resulting work, he blended academic lectures, a review of military history, and armored warfare theory based, in part, on the book Der Kampfwagenkrieg (Tank Warfare) of 1934 by Austro-Hungarian General Ludwig von Eimannsberger. Although limited, the book was successful in many respects. It contained two important questions that would require answers if the army were to be mechanized. How will the army be supplied with fuel, parts and replacement vehicles? And how to move large mechanized forces, especially by road? He answered his own questions in discussions on three general areas: refueling; separate parts; and access to roads.

In 1938 Hitler purged the army of personnel who did not sympathize with the Nazi Party, for which reason Lutz was fired and replaced by Guderian. In the spring of that same year, he had his first experience of commanding a panzer force during the annexation of Austria. The mobilization was chaotic, the tanks ran out of fuel or broke down and the combat capacity of the formation was practically nil. If there had been any real fighting, he would certainly have been defeated. He joined the Führer in Linz as he was on his way from Germany to Austria to celebrate the annexation. Subsequently, he set out to remedy the many problems he had encountered in the panzer force. In the last year, before the outbreak of World War II, he fostered an increasingly close relationship with Hitler. She attended the opera with him and received invitations to dinner. When British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, in his policy of appeasement, ceded the Czechoslovak region of Sudetenland to Hitler through the Munich Agreement, the region was occupied by the XVI Motorized Corps under Guderian.

World War II

Invasion of Poland

On April 3, Hitler issued detailed orders for an attack on Poland, an operation to take place at some as-yet-undetermined time in early September 1939. On April 23, in a long speech to his top officers, explained the general lines of his plan. Among other things, he said that the solution to the main problems of Germany involved the need to expand the Lebensraum (living space) and this was impossible "without invading other countries or attacking the properties of other peoples.". On August 23 (barely a week before the attack on Poland), he signed the German-Soviet Pact with the Soviet Union, which guaranteed him a calm eastern border in the event, more than likely, that the Western Allies carried out their threats and invaded Germany from the west.

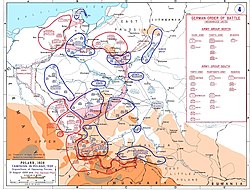

The September campaign was devised by the generalsː Franz Halder, Chief of the General Staff and, mainly, by Walther von Brauchitsch, Army Commander-in-Chief of the Army High Command (Oberkommando des Heeres Apr. OKH). 18th of September. With these troops he formed two groups with the following tasksː

Army Group A (generaloberst Gerd von Rundstedt) stationed to the south in Silesia, was to launch its spearhead, formed by the 10th Army (General der Artillerie Walter von Reichenau), on the Wielun-Warsaw axis. Their flanks would be covered, on the right, by Wilhelm List's 14th Army, and on the left, by Johannes Blaskowitz's 8th Army. To accomplish this task von Rundstedt had thirty-five divisions, including four armored divisions, two motorized divisions, and two motorized S.S. regiments.

Army Group B (generaloberst Fedor von Bock) stationed to the north in Pomerania and East Prussia, initially had to destroy the Polish troops stationed in the so-called "Polish corridor", to later advance towards Warsaw and the Vistula, with the primary objective of preventing the Polish forces from escaping and forming a defense line east of the Vistula. Von Bock had two armies: General der Artillerie Günther von Kluge's 4th Army, which would attack from Pomerania, consisting of six infantry divisions, two motorized divisions and one armored division. And the 3.er Army of General der Artillerie Georg von Küchler, which would attack from Prussia, with eight infantry divisions and one armored division.

In August 1939 Guderian assumed command of the newly formed XIX Motor Corps, integrated into von Kluge's 4th Army. Upon assuming this command he received orders from the OKH that he was to lead the northern grouping of the invasion of Poland, which was to begin on September 1. Under his command, the corps had one of the six panzer divisions that Germany had at that time; The motorized corps controlled 14.5 % of Germany's armored fighting vehicles. His task was to advance through the former territory of West Prussia (which included his birthplace of Kulm), to then advance through East Prussia before heading south towards Warsaw. Guderian used the German concept of "leading forward". », which required commanders to move to the front lines and assess the situation in person. He made extensive use of modern communication systems by traveling in a specially equipped radio command vehicle with which he kept in constant contact with corps command and its forward units.

On 5 September XIX Corps joined German forces advancing west from East Prussia. Guderian had achieved his first operational victory and gave a tour of the battlefield to Hitler and Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, during the tour, when Hitler saw a destroyed Polish artillery post he exclaimed "Did our bombers do that?" "No, our panzers," he replied.The next day, he moved his corps through East Prussia to participate in the advance on Warsaw. On 9 September his corps was reinforced with the 10th Panzer Division and continued its advance inland into Poland, his rapid offensive taking him as far as Brest-Litovsk, where the campaign ended. In ten days, the XIX Motorized Corps had covered 330 kilometres, sometimes against strong Polish resistance. The Panzer divisions had proven to be a powerful weapon, with only eight tanks destroyed out of 350 employees. On September 16, he launched an attack on Brest Litovsk; The next day, the Soviet Union invaded Poland, at which point, they issued an ultimatum to the city's garrison: they had to surrender to the Germans or the Soviets, the garrison capitulated to the Germans. The Soviet Union's entry into the war shattered Polish morale and Polish forces began to surrender en masse. At the end of the campaign, he was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.

Historian Russel Hart wrote that Guderian supported the invasion because "he despised the Polish Catholic Slavs who now occupied parts of his beloved native Prussia." Foremost on his mind was the "liberation" of his old family estate in Gross-Klonia; he ordered the advance on Gross-Klonia at night and through fog, causing what he later admitted were "severe casualties".

During the invasion the German army mistreated and killed Polish prisoners of war, ignoring both the Geneva Convention and their own military regulations. Guderian's Corps withdrew before the SS began its campaign of ethnic cleansing (see German war crimes in Poland). Even so, he found out about the operations of murder and deportation of Jews in Nazi ghettos thanks to his son, Heinz Günther Guderian, who had witnessed some of them. There is no record that he made any protest.

Invasion of France, Belgium and the Netherlands

Later, he participated in the strategic discussions that preceded the invasion of France and the Netherlands. The plan was being developed by his classmate at the 1907 War Academy, Erich von Manstein. The plan the latter developed, later known as the Manstein Plan, shifted the weight of armored formations from a frontal attack through the Netherlands to a flank attack through the heavily forested Ardennes region. Guderian expressed confidence in the feasibility of moving tanks through a region with such difficult terrain, and was later informed that he might have to spearhead the attack himself. He then complained about the lack of resources until he was assigned seven mechanized divisions with which to carry out the task. The plan established a force for the penetration of the forest that included the largest concentration of German armor to that date: 1,112, out of the total of 2,438 that Germany had at that time.

Guderian's corps led the attack through the Ardennes and over the Meuse River. He led the attack that broke through the French lines at the Battle of Sedan. His panzer group led the so-called "rush to the sea", which ended with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and French forces trapped at Dunkirk. A British counter-attack at Arras on 21 May slowed the German advance and allowed the BEF to establish strong defenses around the evacuation points, while Hitler, who feared possible French counter-attacks and was reluctant to allow the use of armor without infantry support in the urban fighting, ordered a halt to the advance. A general resumption of the attack was decided on on 26 May, but by then the Allied forces had regrouped, allowing them to put up a stiff resistance. On 28 May, with his losses mounting, he advised abandoning the armored assault in favor of a traditional artillery-infantry operation. He later attacked eastern Paris and was then ordered to advance towards the Swiss border. The offensive began on the Weygand Line on June 9 and ended on June 17 with the encirclement of the Maginot Line defenses and the remaining French forces. Their tanks moved so fast that the French were overwhelmed, and even the High German command expressed doubts when reported that it was on the Swiss border.

Despite the success of the invasion, French defeat was not inevitable; the French had more and better military equipment, and were not overwhelmed by superior numerical or technological military force. In fact, the French defeat was due to other factors, such as low army morale, an outdated military strategy, an inoperative High Command, and a lack of coordination among the Allied troops. Hitler and his generals became overconfident after their historic victory and came to believe that they could defeat the Soviet Union, a country significantly better endowed with natural resources, manpower, and industrial capacity.

Invasion of the Soviet Union

In his book Achtung - Panzer! In 1937 he wrote that "the time has passed when the Russians had no instinct for technology" and that Germany would have to face "the Eastern question more seriously than ever in history". Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union, had become optimistic about the alleged superiority of German weapons. In May 1941 he had accepted Hitler's official position that Operation Barbarossa was a pre-emptive strike, he had even accepted some central elements of National Socialism: such as the Lebensraum concept of territorial expansion and the destruction of the supposed threat of Judeo-Bolshevism.

Guderian's 2nd Panzergruppe began its offensive on June 22 by crossing the Bug River and advancing towards the Dnieper. The combined forces of the 2nd and 3rd Panzergruppe closed the Minsk Pocket, capturing 300 000 prisoners before advance towards Smolensk. He was awarded the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves on 17 July 1941. Following the conclusion of the Battle of Smolensk on 15 July which ended with the encirclement and destruction of the 16th, 19th and 20th. In the Soviet armies, the Germans were only 200 miles from Moscow and the Red Army had barely a handful of decimated divisions to stop their advance, which is why Generaloberst Franz Halder, OKH chief of staff, argued in favor of an all-out attack on Moscow.

On August 18, Halder sent a detailed attack plan against Moscow to Hitler, which he rejected. But Halder did not give in, he went to the Headquarters of Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock commander of Army Group Center, in the surroundings of Minsk, where he met with the main commanders subordinate to von Bock. At that meeting, at Halder's proposal, it was decided to send Guderian to the Führer's Headquarters to change Hitler's "unchangeable decision" to divert troops south to conquer Kiev and the western part of Ukraine. Hitler's close relationship with Guderian, with whom he had gone to the opera several times before the war, made him ideally suited for this mission. At the meeting with Hitler, Guderian, who had recently vehemently opposed the plan Hitler for the turn to the south, unexpectedly sided with the dictator. This abrupt change of heart so enraged Halder that in a telephone conversation with von Bock, he complained bitterly that he had left them "in the lurch."

The version that Guderian later told his commanding officers, Kurt von Liebenstein and Fritz Bayerlein, was diametrically opposedː «There was nothing I could do, gentlemen. I faced the solid front of the High Command. Everyone present agreed with every sentence the Führer said, and I did not receive any support for my ideas. He then he added «Now we can't start crying about our plans. We have to fulfill our new task". Halder subsequently attempted once more to dissuade Hitler from diverting armored troops from the attack on Moscow but Hitler had made his decisionː "enemy or no enemy, or no other consideration, the Führer is not interested right now in Moscow; All he cares about is Leningrad,' Halder noted angrily in his diary. Following Hitler's orders the 2nd Panzergruppe would advance southwest towards kyiv and Hermann Hoth's 3rd Panzergruppe was to divert its tanks north to aid the capture of Leningrad.

By 15 September German forces including 1st Panzergruppe (Ewald von Kleist) and 2nd Panzergruppe (Heinz Guderian) had completed the encirclement largest in history, the battle of Kiev. Due to the southward turn of 2nd Panzergruppe during the battle, the Wehrmacht destroyed the entire Southwestern Front east of Kiev, inflicting more than 600 000 losses to the Red Army before September 26. However, the campaign had been costly; German forces had only half as many tanks as they had three months earlier, had suffered 522 800 casualties mainly in infantry units, many of them which only had a third of its authorized force, the Luftwaffe barely had 1,005 operational aircraft on September 6 and the situation was much worse in the case of trucks, ammunition and, above all, fuel. The 2nd Panzergruppe had suffered the most losses; only 21 % of their tanks were operational. In mid-September Hitler ordered it to make a new turn, north towards Moscow, retracing its way to the Smolensk area. "At last the preliminary conditions have been achieved that allow us to execute a last and powerful blow that will lead to the annihilation of the enemy before winter", said the new directive of the Führer. "Today begins the last great battle of this year." This turn to the north involved a huge logistical effort that consumed a large amount of fuel of which the Wehrmacht was very short.

The advance towards Moscow

Time was running out for the Germans by the end of September, frequent rains and icy nights heralding the bitter winter to come. Guderian was the first to attack on 28 September when he sent his XXXXVIII Motorized Corps on a probing attack against the Soviet Bryansk and Southwestern fronts. This first attack was repulsed by the Soviets after a series of savage counter-attacks, forcing Guderian's spearhead, the 25th Motorized Division, to withdraw after suffering heavy losses.

However, the main attack was delayed until October 2. After a brief artillery preparation, supported by a series of devastating air strikes, the 4th Panzergruppe succeeded in breaking through the Soviet lines, enveloping the southern flank of the Soviet 43rd Army in its advance. At the same time the 3rd Panzergruppe penetrated between the 19th and 30th Armies northwest of Viazma. The two armored vanguards continued to advance until, on 8 October, they linked up east of Viazma encircling most of the Soviet 19th, 20th, 24th and 32nd Armies in a large pocket. Although in this case most of the encircled troops were able to escape in small groups after destroying their heavy equipment. The surviving Soviet troops fell back to the next line of defense established around Mozhaisk and Kaluga just 110 kilometers west of Moscow.

Further south, on October 2, 2nd Panzergruppe had penetrated the lines of defense of the Soviet 13th Army under Avksenti Gorodnianski and, the next day, occupied Orel. Just north of Guderian's armored advance, Maximilian von Weichs' German 2nd Army encircled the Soviet 13th and 50th Armies in two large pockets around Briansk, however Guderian was more interested in continuing. their advance towards Moscow than in cooperating with the 2nd Army in destroying the encircled Soviet troops, which is why large numbers of Soviet soldiers were able to infiltrate between the German lines and withdraw to a new Soviet line of defense in Mtsensk. On October 7, Hitler authorized Guderian to continue his attack on Moscow. However, muddy roads, fuel shortages, and an increasingly resolute Soviet defense slowed, almost stopped, the German advance.

On October 4th the 4th Panzer Division, part of the 2nd Panzergruppe suffered a severe setback at Mtsensk, near Oryol, when its troops faced a counterattack by a Soviet unit equipped with T-34 tanks, for the first time German casualties exceeded Soviet ones. Guderian demanded an inquiry into the realities of tank warfare on the Eastern Front, eventually suggesting in November that major tank designers and manufacturers Germans that the quickest solution was to produce a direct copy of the Soviet tank. Even Guderian himself was forced to admit that his enemies were learning.

On October 28, Hitler sent new orders to the 2nd Panzergruppeː to send "fast units to seize the bridges over the Oka River east of Serpukhov" an objective that was more than 120 kilometers away away at a time when Guderian's troops could barely advance at an average of ten miles a day. On November 13, Halder met at Orsha halfway between Minsk and Smolensk, the headquarters of Army Group Center, with the top German commanders. Most of them agreed that the offensive had to stop, General Kurt Freiherr von Liebenstein, chief of staff of the 2nd Panzergruppe, speaking for Guderian, exclaimed that the rapid advance of the panzer divisions in spring weather could not be doubled in bad weather. One important exception was Fedor von Bock commander of Army Group Center who expressed his opinion that the advance should continue. In any case, Halder had arrived at the meeting with a new directive from the Führer ordering to resume the advance on Moscow. "It is the Führer's wish," he said laconically.

New OHK orders called for a pincer attack on Moscow. Thus the 3rd and 4th Panzergruppe were to attack towards Klin, then they would cross the Moscow-Volga canal and surround Moscow from the north. In the center the 4th Army under Günther von Kluge would make a frontal attack on the city, while Guderian's 2nd Panzergruppe would attack from the southwest towards Tula and Kashira to link up with the panzer vanguards of the 3rd and 4th Panzergruppe somewhere east of Moscow.

By November 15, the ground had frozen sufficiently for the Germans to resume their offensive; although the cold brought new miseries to the invaders, ill-equipped to withstand the harsh Russian winter. The attack by 2nd Panzergruppe in the direction of Tula and Kashira, 125 kilometers south of Moscow, began on 18 November but achieved only limited success. Guderian had concentrated most of the forces. tanks, which he still had available, in a brigade under the command of Oberst Heinrich Eberbach who was to lead the offensive. Eberbach advanced slowly in an attempt to encircle Tula from the east before attacking Moscow. Lieutenant General Ivan Boldin's Soviet 50th Army, defending Tula, launched repeated counterattacks against the limping German advance. Due to persistent Soviet counter-attacks, enormous logistical difficulties, and a harsh winter with temperatures well below freezing, the German advance slowly slowed to a halt, without Tula being captured.

In the center, on December 1, von Kluge's German 4th Army, after considerable delay, attacked east along the Minsk-Moscow highway and ran into a series of well-placed Soviet defensive lines. fortified and equipped with abundant material. At the same time, Mikhail Efremov's Soviet 33rd Army struck the German advance on the flanks, forcing the 4th Army to a complete halt, on 5 December, well short of its intended objectives.

Guderian blamed the slow engagement of the 4th Army in the attack for the German failure to reach Moscow. This assessment vastly overestimated the combat capability of Kluge's remaining forces, severely lacking in armor support and severely weakened after months of heavy fighting. He He, too, failed to appreciate the reality that Moscow was a metropolis where German forces lacked sufficient numbers to encircle or capture in a frontal assault. In the aftermath of the German defeat, he refused to transmit Hitler's order to "stand firm" and had serious clashes with Günther von Kluge, the new commander of Heeresgruppe Mitte (Army Group Center). On the night of December 5 he withdrew his main units to a more defensible line south of Tula and ordered them to dig in, thus disobeying Hitler's orders. That same night the 4th Panzergruppe and the 3rd Panzergruppe also suspended their attacks and began to withdraw. "The Führer's order," wrote General Liebenstein, chief of staff of the 2nd Panzergruppe, "does not correspond in any way to reality. Despite all the requests and reports, those at the top have not understood that we are too weak to even defend ourselves." On December 20, he flew to Rastenburg to explain his situation to Hitler and to insist that his forces should be evacuated to more defensible positions.. On December 25, 1941 after a new discussion with Kluge, he was relieved of command.In addition to Guderian, Generals Hoepner, Brauchitsch, Rundstedt and Bock were also relieved, more than thirty generals in all.

German formations on the Eastern Front ubiquitously implemented the Order of the Commissars and the Barbarossa Decree. For all divisions within Guderian's panzer group where files are kept, there is evidence of illegal reprisals against the civilian population. In his memoirs he denied having transmitted the Order of the Commissioners to his troops. However, General der Panzertruppe Joachim Lemelsen, commander of the XLVII Motorized Army Corps included in the 2nd Panzergruppe, assured that he is documented saying that “the prisoners, who it could be shown that they were commissars they should be removed immediately and shot" and that the order came directly from Guderian. It is also documented that in a communication with the OKW he reported that his panzer group had "removed" 170 commissars at the beginning of August.

Inspector General of Armored Troops

On March 1, 1943, the German defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad and the poor state of the panzer divisions prompted Hitler to bring Guderian out of forced retirement and appoint him to the newly created post of inspector general of the Armored Troops. In view of the convoluted German bureaucracy, he insisted on reporting only to Hitler, which meant they had wide latitude to develop their ideas on the development of the panzer weapon.

Guderian's new responsibilities included both authority in tank production and in the organization, doctrine and training of the Panzerwaffe including panzer units attached to the Waffen-SS and the Lutfwaffe (in the latter case basically the Hermann Göring Division). In view of an adequate fulfillment of his obligations, he established a close collaboration relationship with Albert Speer, at the time Minister of Armaments and War Production, mainly with respect to the manufacture and development of new armored fighting vehicles. Despite His efforts The military failures of 1943 prevented him from restoring the combat power of the armored forces to any significant degree. He also had limited success designing new and improved tank destroyers and repairing the many design flaws found in the third generation tanksː the Panzer V Panther, Panzer VI Tiger, and the Elefant heavy tank destroyer.

In the spring of 1942 the first panzer divisions to receive the first Panther models discovered a series of design errors, especially in the steering gear. All 325 Panthers available at the time had to be sent back to the factory for reconditioning. Approximately two hundred of these Panthers returned to their units, however as of June 16, 1943 Guderian reported that 65 of those tanks were still in trouble. In the case of the Panzer VI Tiger the situation was similar, its manufacture was so complicated that more than 300 000 man-hours of work were needed at a cost of 800 000 Reichmarks to make each tank, which is why only 178 were available for the July 1943 offensive. Furthermore, the tank was so complex that it required a constant maintenance, his speed was only 27 km/h, which is why he was included in independent armored battalions, since he was unable to keep up than the fast Panzer IV and Panzer V Panther. The Tiger was so heavy that the bridges and railway platforms were unable to support its enormous weight of sixty tons, so the Germans had to build special bridges and platforms. All these factors greatly limited the usefulness of these new tanks.

Operation Citadel, the last major German offensive operation in the east, was an attempt by the German army to regain the initiative in order to prevent defections among its satellite countries and to raise the morale of the German troops and civilian population When finding any limited targets, the Germans focused on the Kursk salient. Salient that had formed after the Soviet offensive in February and March 1943. If the Germans removed this salient they could destroy large numbers of Soviet troops, shorten the front and free up troops for future operations. Guderian was opposed to the offensive, he wished to stay on the defensive for the rest of 1943 to rebuild the panzer gun, badly depleted after the last fighting. On 3 May 1943 Hitler attended a meeting in Munich to discuss the details. of the offensive. At that meeting Walter Model, commander of the 9th Army, advised against attacking because of the elaborate defenses the Soviets had built at the main German attack points, which clearly showed that the Soviets were aware of the upcoming German offensive.. Erich von Manstein, commander of Army Group South agreed with Model and also advised against attacking, but Günther von Kluge, commander of Army Group Center and Kurt Zeitzler, chief of the OKH General Staff, advised to continue with the operation. Zeitzler argued that the new tank models would give the Germans a clear technological advantage, but Guderian and Albert Sperr objected that severe technical problems, especially those associated with the Panthers, would limit this supposed technological superiority.

A week after the Munich meeting, in a private conversation with Hitler before the offensive, Guderian said: "Why are we attacking in the East this year?" Hitler replied: "You are right, when I think about the attack my stomach turns." Guderian concluded: “Then you have the right attitude towards this situation. Let it run". The Battle of Kursk was a costly failure that considerably depleted the already scarce resources available to the Wehrmacht, especially serious were the losses suffered by panzer units estimated between 760 and 1,200 tanks and assault guns. The Soviet losses were greater but thanks to its superior industrial capacity and its larger population it was able to recover in a relatively short time. Even the recent German industrial mobilization, fueled by slave labor provided by millions of citizens of the occupied countries and led by such efficient and cruel men as Guderian, Speer, or Fritz Sauckel, was barely enough to patch up existing units. Despite new, technologically advanced models of aircraft and tanks being designed, Germany was unable to produce, equip, and refuel enough to counter the enormous industrial capacity of the United States and the Soviet Union.

Chief of the General Staff of the Army

After the failed attack on Hitler on July 20, 1944, Guderian led a military occupation of Berlin with his tanks, took control of the Bendlerblock in order to definitively discourage the Putsch attempt. On July 21, 1944 Hitler appointed him chief of the Army General Staff (Chef des Generalstabs des Heeres) of the OKH with the responsibility of advising the Führer on the Eastern Front. The reason for his appointment over other more capable officers and with more experience, it is simple he was the only general who enjoyed Hitler's confidence and had not been injured or killed in the attack. He replaced general der infanterie Kurt Zeitzler, who had left office on July 1, after losing faith in Hitler's trial and suffering a nervous breakdown. Five days after the attack and already in his new position, eager to gain Hitler's trust, he addressed the state officials Army major using an esc a rite with a great political charge and where his position on the attack was clearly reflected.

The great confidence that Hitler had in Guderian was decisive for him to put him, on August 4, 1944, in charge of the Army Court of Honor, together with Gerd von Rundstedt and Wilhelm Keitel, The general der infanterie Walter Schroth and Karl Kriebel were also part of this court; General der infanterie Wilhelm Burgdorf and Generalmajor Ernst Maisel attended the deliberations as Hitler's observers. >Wehrmacht to those suspected of involvement in the armed forces plot, only to be handed over to the Volksgerichtshof (People's Court) run by the infamous judge Roland Freisler created to try the alleged conspirators. The defendants were tortured by the Gestapo and executed by hanging. Some conspirators were hung from a thin hemp rope on Hitler's direct order. Guderian and the other members of the tribunal expelled a first group of twenty-two officers, without hearings or review of the evidence, basing their decision solely on a brief statement by Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Head of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) and in the minutes of the interrogations carried out by the Gestapo. In total, more than fifty officers were expelled from the Wehrmacht during the months of August and September. Kluge, who would commit suicide weeks later. Guderian himself denied being involved in the plot; however, he had unexpectedly retired to his estate on the day of the assassination attempt.

After the war, he claimed that he had tried to escape this "duty" and found the court sessions "repulsive." He In fact he had applied himself to the task with the vigor of an ardent Nazi supporter, perhaps due to a desire to divert attention from himself. In this regard, the American historian Russell Hart wrote in his book Guderian: Panzer Pioneer or Mythmaker? that he fought to save Rommel's chief of staff, Hans Speidel, because he could have implicated him in the plot..

As head of OKH he faced the pressing problems of staff work being affected by arrests, which between OKH staff and their families eventually numbered several hundred. he had to fill important gaps, such as the one created by the suicide of General Eduard Wagner, the quartermaster general, in July. Even after filling all the vacancies, a key problem remained: too many staff members were new to their roles and lacked institutional knowledge, including Guderian himself. He had great confidence in Colonel Johann von Kielmansegg, who was the most experienced staff officer in the OKH, but he was arrested in August. The situation was not improved by his confrontation with the General Staff, which he blamed for having opposed his attempts to introduce modern armored doctrine into the army in the 1930s. The last months of 1944 were marked by fighting every between the OKH and the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) as the two organizations competed for dwindling resources, especially in the run-up to the Battle of the Bulge. After the war he blamed Hitler for wasting the last German reserves on the operation; yet the strategic situation in Germany was such that even twenty or thirty more divisions would not have made any difference.

After the failed assassination attempt on Hitler, Guderian completed the full Nazification of the army staff with an order on 29 July requiring all Wehrmacht officers to join the NSDAP (National Socialist Workers' Party). German). He demanded the resignation of any German officer who did not fully support the ideals of the NSDAP and made the Nazi salute compulsory in all the armed forces. He supported the politicization of the military, despite all these deeply political measures, he did not understand why the other officers considered him a Nazi. As OKH chief of staff, he did not oppose the orders issued by Hitler and Himmler during the brutal suppression of the Warsaw uprising or the atrocities committed against the city's civilian population. Lest there be any doubt about his evident alignment with Nazism, in November 1944, in a speech at a Volkssturm rally, he said that there were "95 million National Socialists who back Adolf Hitler."

By the Soviet Vistula-Oder Offensive of early 1945, the Red Army had lined up large numbers of men and weapons along the Vistula front, outnumbering their enemies. The intelligence chief of the Foreign Armies Department of the East (German: Fremde Heere Ost, abr. FHO) in the General Staff of the German Army, Generalmajor Reinhard Gehlen, gave Heinz Guderian his impressions of the nature of the Soviet attacking force. He presented the data to Adolf Hitler, who dismissed the apparent real strength of the adversary as "the greatest impostor since Genghis Khan". Since the divisions that had participated in the failed German Ardennes Offensive on the Western Front could not be directed Quickly to Poland, Guderian proposed to evacuate what was left of Army Group North trapped in the Courland pocket towards Germany and thus reinforce this front, something that Hitler flatly rejected. In addition, Hitler ordered Sepp Dietrich's 6th SS-Panzer Army, which had also participated in the Ardennes offensive, to move into Hungary to support the Lake Balaton offensive.

As Guderian was about to leave the meeting, Hitler remarked: 'The Eastern Front has never had such a powerful reserve as it does right now, and that was their doing. Thank you". "The Eastern Front," replied Guderian, "is like a house of cards, it is enough to break it at one point and it will collapse in its entirety." Curiously, Goebbels had used the same simile in 1941 on the eve of the German invasion of the Soviet Union to refer to the Red Army.

After the war he claimed that his actions in the final months of the war as head of OKH were driven by a search for a solution to Germany's increasingly bleak prospects. This was supposedly the rationale behind Guderian's plans to turn major urban centers along the Eastern Front into so-called fortress cities ("Feste Plätze"). This fantastic plan had no hope of success against the mobile operations of the Red Army. In view of its enormous material and manpower superiority, the Red Army could afford to continue its advance and leave behind the corresponding contingents of infantry troops, to subsequently destroy Guderian's 'strongholds'. He knew that these fortresses were doomed to failure, since the lack of fuel and aircraft suffered by the Luftwaffe made it impossible to supply them by air, and his policy deprived the weakened Wehrmacht of a large number of experienced troops.

In March 1945 after the Vistula-Oder Offensive, the Soviet advance towards Berlin had come to a halt along the Oder River. However, Marshal Georgy Zhukov's First Ukrainian Front had occupied two bridgeheads around Küstrin (Nikolai Berzarin's 5th Shock Army to the north and Vasily Chuikov's 8th Guards Army to the south) about fifty miles to the south. East of Berlin. Therefore, Hitler ordered to launch a counteroffensive against the southern Chuikov pocket, in order to help the German garrison surrounded in the city.

On March 27, the 9th German Army launched the projected counterattack, with four divisions from Frankfurt on the Oder, against the southern flank of Chuikov's 8th Guards Army. The offensive surprised the Soviets and reached the suburbs of Kustrin. However, Chuikov quickly recovered from the initial surprise and the Germans were decimated in the open field, mainly by Soviet artillery and aircraft, and were forced to withdraw to their initial positions after suffering heavy casualties. Guderian defended against Hitler the actions of the commanders involved in the failed operation, Generals Theodor Buse and Gotthard Heinrici. On March 28, he was granted leave "due to ill health" and was replaced by General der Infanterie Hans Krebs, who would eventually become the Army's last Chief of General Staff.

Guderian cultivated close personal relationships with the most powerful people in the regime. He had an exclusive dinner with Himmler on Christmas Day, 1944. On March 6, 1945, shortly before the end of the war, he participated in a Holocaust-denying propaganda broadcast; despite the fact that the Red Army in its advance had just liberated several death camps. Despite the general's later claims to be anti-Nazi, Hitler likely found Guderian's values to be closely aligned with Nazi ideology, which is why he brought him out of retirement in 1943 and was especially appreciative of the orders he issued after the failed plot.

Postwar

Guderian and his staff surrendered to American forces on May 10, 1945. He avoided conviction as a war criminal at the Nuremberg trials because there was no substantial documentary evidence against him at the time. He answered questions of the Allied forces and denied being an ardent supporter of Nazism. In 1945 he joined the US Army Historical Division. For this reason, the Americans refused continuous requests from the Soviet Union and Poland for his extradition. Even after the war, he maintained a clear affinity with Hitler and National Socialism. While he was interned by the Americans, his conversations were secretly recorded. In one of those recordings, while conversing with former Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb and former General der Panzertruppen Leo Geyr von Schweppenburg, he opined that: «The fundamental principles of Nazism they were fine."

He was released from captivity without trial in 1948, although many of his comrades were not so lucky, for example Erich von Manstein was sentenced to eighteen years and Albert Kesselring to life imprisonment. The reasons for this soft treatment are simple: he had reported on his former colleagues and cooperated with the Allies, which had helped him evade prosecution. After his release he retired to Schwangau near Füssen in southern Bavaria and began writing his memoirs, his most successful book being his autobiography Memories of a Soldier (German: Erinnerungen eines Soldaten) published in 1950. He eventually died on May 14, 1954 at the age of 65 and was buried at Friedhof Hildesheimer Straße in Goslar.

Writings and mythology

Myth of the Panzer Leader

Guderian's postwar autobiography, Recollections of a Soldier, was a hit with the reading public. In this autobiography he presented himself as an innovator and the "father" of the German armored arm, both before the war and during the blitzkrieg years. envisioning himself as the master of blitzkrieg between 1939 and 1941; however this was an obvious exaggeration. Guderian's German memoirs were first published in 1950. At that time they were the only accessible source on the development of panzer forces, as German military records were either inaccessible or lost. Consequently historians based their interpretation of historical events on Guderian's highly egocentric autobiography. Later biographers supported the myth and embellished it. In 1952 Guderian's memoirs were reprinted in English. British military theorist and journalist Liddell Hart, after gaining access to a group of Wehrmacht generals imprisoned in POW Camp No 1 at Grizedale Hall in northern England due to As a lecturer for the Department of Political Intelligence participating in the Re-education Program, in an effort to use his privileged access to Guderian and other German officers he asked Guderian to say that he had based his military theories on those of Liddell Hart, with the in order to enhance his own reputation as a military theorist and commentator; he accepted. Liddell Hart, for his part, became an enthusiastic advocate of West German rearmament and the myth of the innocent Wehrmacht.

In more recent scholarship, historians began to question Guderian's memoirs and criticize the myth they had created. Battistelli, examining Guderian's record, said that he was not the father of the panzerwaffe, but merely one of several innovators. The reasons why he stood out from his arguably more capable compatriot Lutz were basically two: in firstly, he sought to be the center of attention and, secondly, he fostered a close relationship with Hitler and the Nazi regime. By presenting himself as the father of blitzkrieg and ingratiating himself with the Americans, he avoided being handed over to the Soviet Union and Poland, whose extradition they persistently requested to answer for war crimes committed by troops under his command. in those countries. Battistelli wrote that his most remarkable ability was not as a theorist or commander but as an author. His books Achtung-Panzer! and Recollections of a Soldier were a critical and commercial success upon publication and continue to be discussed, researched and analyzed sixty years after his death.

Guderian was a capable tactician and technician, leading his troops successfully in the invasion of Poland, the battle of France and during the early stages of the invasion of the Soviet Union, notably the battle of Smolensk and the battle from Kiev. Hart wrote that most of his success came from positions of such strength that he could hardly lose: he "could never achieve victory from a position of weakness." Hart added that his strengths were outweighed by his shortcomings, such as deliberately creating animosity between his armored force and other military weapons, with disastrous consequences. His memoirs omitted to mention his military mistakes and his close relationship with Hitler. James Corum wrote in his book The Roots of Blitzkrieg: Hans von Seeckt and German Military Reform that he was an excellent general, a first-rate tactician, and a man who played a central role in the development of the Panzer divisions, regardless of their memories.

Myth of the innocent Wehrmacht

Battistelli wrote that Guderian rewrote history in his memoirs, but notes that the biggest rewriting in history occurs not in his alleged paternity of the panzer force, but in the cover-up of his culpability for war crimes committed during the war. Operation Barbarossa. Units under his command carried out the infamous Order of the Commissars, which involved the assassination of Red Army political officers. He also played an important role in the commission of reprisals after the Warsaw uprising of 1944.

Like other generals, Guderian's memoirs emphasized his loyalty to Germany and the German people; however, he neglected to mention that Hitler bought this allegiance with bribes, including landed property and a monthly payment of 2,000 Reichsmarks. Guderian wrote in his memoirs that he had been given a Polish inheritance as a retirement gift, worth 1, 24 million Reichsmarks, the estate covered an area of 2,000 acres (809.4 ha) and was situated in Deipenhof (present-day Głębokie, Poland) in the Warthegau area of occupied Poland (Wartheland Reichsgau). The owners had been evicted and the estate requisitioned. He also did not mention that he had initially applied for an estate three times as large, a request that was refused by Arthur Greiser the local Gauleiter, with Himmler's support. The Gauleiter was reluctant to give such an opulent estate to someone who only held the rank of Colonel General.

In 1950 he published a pamphlet entitled Can Western Europe Be Defended? (German: Kann Westeuropa verteidigt werden?) where he lamented that the powers Westerners had chosen the wrong side to ally themselves during the war, even as Germany "was fighting for its very existence" as "the defender of Europe" against the supposed Bolshevik threat. Guderian issued an apologetic for Hitler in which he wrote: "Because one can judge Hitler's acts however one likes, in retrospect his fight was for Europe, even if he made terrible mistakes and mistakes." He claimed that only the Nazi civilian administration (not the Wehrmacht) was responsible for the atrocities committed against Soviet civilians and made Hitler the scapegoat and the Russian winter the sole reason for the military setbacks of the Soviet Union. Wehrmacht, as he did later in his autobiographical book Memories of a Soldier; furthermore, he wrote that six million Germans died during their expulsion from the territories of Eastern Europe by the Soviet Union and its allies, while also writing that the defendants executed at the Nuremberg trials (for war crimes such as the Holocaust) were "defenders of Europe".

Historians Ronald Smelser and Edward J. Davies, in their book The myth of the eastern front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture, conclude that Guderian's memoirs are full of « egregious falsehoods, half-truths, and glaring omissions" as well as outright "nonsense." Guderian claimed, contrary to historical evidence, that the commissars' criminal order was not carried out by his troops because "it never reached [his] panzer group of his." He also lied about the Barbarossa Decree preemptively exempting German troops from prosecution for crimes committed against Soviet civilians, claiming that it was not carried out either. He claimed to have been solicitous to the civilian population, that they strove to preserve Russian cultural objects, and that his troops had "liberated" Soviet citizens.

British historian David Stahel wrote that English-speaking historians too easily presented a distorted picture of German generals in the postwar era. In his book Operation Barbarossa and Germany's defeat in the East, wrote:

The men who controlled Hitler's armies were not honorable men, who fulfilled their orders as obedient servants of the state. With resolute support for the regime, the generals certainly waged a war of aggression after another, and once Barbarosja began, they voluntarily participated in the genocide of the Nazi regime.

In July 1976 the leading American war gaming magazine, Strategy & Tactics, selected him in the featured game of the month called Panzergruppe Guderian. The magazine's cover featured a photo of him in military attire, with his Knight's Cross and binoculars, suggesting a command role. The magazine featured a glowing profile of Guderian where he was identified as the creator of blitzkrieg and praised for his military achievements. Following post-war myths, the profile posited that such a commander could "work in any political climate and remain unaffected by it." Guderian thus presented himself as a consummate professional who stayed out of the crimes of the Nazi regime.

Writings

- - (2007). Memories of a soldier (1st edition). Unpublished Editors. ISBN 978-84-96364-80-6. OCLC 433647706.

- - (2011). Achtung-Panzer!: the development of the armoured, their combat tactics and their operational possibilities. Tempus/ Books of Atril S.L. ISBN 978-84-92567-35-5. OCLC 1010979777.

- - (1942). Mit Den Panzern in Ost und West [chuckles]With the Panzers in East and West] (in German). Volk & Reich Verlag. OCLC 601435526.

- - (1950). Kann Westeuropa verteidigt werden? [chuckles]Can Western Europe be defended?] (in German). Göttingen: Plesse-Verlag. OCLC 8977019.

Contenido relacionado

Sepulveda

Annex: Municipalities of Michoacán

Jean Seberg