Hatti

Hatti or Hittite Empire was an Ancient State that originated around the 17th century BC. C. and succumbed around the 12th century B.C. It was a dominant power in Anatolia, where its central political core and other peripheral territories were located. During the XIV centuries and XIII a. C., the Hittites incorporated a large number of Anatolian vassals in the West and controlled large areas of the Mediterranean Levant and upper Mesopotamia, reaching the Euphrates River. Their political-military organization was complex.

Their capital was Hattusa. They spoke an Indo-European language, written in hieroglyphics or cuneiform borrowed from Assyria. His kingdom brought together numerous city-states of very different cultures between them and came to create an influential empire thanks to its military superiority and diplomatic skill, making it the "third" power in the Near East at the time, along with Babylon. and Egypt. They perfected the light battle tank and used it with great success. They are credited with one of the first uses of iron in the Near East to make weapons and luxury items. After their decline, they fell into oblivion until the 19th century

Archaeology

Thanks to numerous excavations, some as important as the discovery of what would be similar to a "national archive" in Hattusa, and many references in texts of Assyrian and Egyptian origin, it has been possible to reconstruct its history and decipher its writing.

Hatti's name

It is not known for sure what they called themselves. The name of Hatti comes from the Assyrian chronicles that identified it as "Khati" (the country of Hatti), and on the other hand the Egyptians called them "Heta", which is the most common transcription of the hieroglyph "Ht" (Egyptian writing lacked vowels).

In Assyrian and Akkadian language URUHa-at-ti.

On the other hand, the Hatti were a non-Indo-European people who lived in the same region as the Hittites, before the first Hittite empire, and whose conquest by the latter caused the Assyrians and other neighboring states to continue using the name from hatti to denote the new occupants, coming to mean 'the land of the city of Hattusa'. The Hattic language of the Hatti continued to be used occasionally and for certain purposes within of the inscriptions in Hittite.

The term comes from Biblical references. This was called Hittim, which Luther would translate into German as Hethiter, the English turned it into Hittites, while the French first called them Héthéens to end up calling them the same way as the English, Hittites. "Hititas" is the general term used in Spanish ("hittites" has also been used, but it is infrequent and out of use). References in the Bible about the Hittites are found in Genesis (15:19-21 and 23:3), Numbers (13:29), Joshua (3:10) and Book II of Kings (7:6).

In the book of 2 Samuel (11:1-21), reference is made to Uriah the Hittite, a fighter in King David's armies and husband of Bathsheba. After taking her as a concubine while Uriah fought with the Ammonites, David, after impregnating Bathsheba, caused her death.

The discovery of the Hittites

Unlike the contemporary kingdoms of Babylon, Assyria or Egypt, whose memory has been present in successive civilizations, the Hittite Kingdom is part of those forgotten by the ancient history of the Near East. Like Sumerians, Elamites or Urartians, they left hardly a trace in the memory of the peoples who later occupied their lands. Bas-reliefs of the Hittites and their vassals, such as the one at the Karabel Pass in Kemalpaşa, have been well known since ancient and medieval times, but their attribution remained problematic until the late 19th century XIX.

In 1834 Charles Texier discovered the ruins of an ancient city near the Turkish village of Bogazköy (later identified as its former capital, Hattusa). In 1839, in his book Description de l'Asie Mineure he states that these ruins belonged to an unknown civilization.

In 1822, in Travels through Syria and the Holy Land, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt talks about finding a tombstone with unknown hieroglyphics, something that happened unnoticed at the time. But in 1863, the Americans Augustus Johnson and the director Jessup would follow Burckhardt's tracks in Hama until they found her again.

Between 1870-80 various remains were investigated by the Irish missionary Willian Wright, who moved some stones to Istanbul, and H. Skeene and George Smith, who discovered Karkemish and found remains of the "unknown script", the same script that would meet in 1879 Henry Sayce in Smyrna.

In 1880, Sayce stated in a lecture before the Society for Biblical Archeology that all these remains belong to the "Hittites" mentioned in the Bible. Four years later, William Wright provides new evidence for Sayce's thesis and publishes a controversial and daring treatise: The great Empire of the Hittites, with the decipherment of the Hittite inscriptions by Professor A.H. Sayce.

Around 1887, numerous Egyptian documents from the time of Akhenaten were discovered in Amarna, including abundant correspondence with the first direct allusions to the Hittites and the Jebusites. In 1888, Karl Humann and Felix von Luschan conducted excavations at Sendjirli and discovered a Hittite fortress with numerous bas-reliefs and tons of sculptures and clay pottery. Between 1891 and 1892 William Flinders Petrie finds tablets in the same "unknown language", which would first be called the "Arzawa language", due to the allusions made to the Arzawa territory. In 1893 the French archaeologist Ernest Chantre discovered in Bogazköy fragments of tablets in the same language.

But the greatest discovery was made by Hugo Winckler between 1905 and 1909 on an expedition to Bogazköy, where he found more than 10,000 tablets from what seemed to be a "national archive", among which there were bilingual texts, which allowed deciphering numerous documents. Winckler affirms that these ruins belong to the capital, which he ends up calling Hattusa. From then on, research between 1911 and 1952 focused on deciphering the Hittite language, whose greatest contributions were made by Johannes Friedrich who, in 1946, published a Hittite Manual and between 1952 and 1954 a Hittite language dictionary.

The highlight of the Hittite discovery comes during excavations led by Kurt Bittel at Bogazköy and Helmut Bossert's excavations at Karatepe, where new bilingual texts have been found that have helped definitively decipher Hittite writing and dating.

History

Hittite history spans approximately five hundred years, from the reign of Labarna to the early 17th century BCE. until the collapse of the kingdom at the end of the 13th century BC. C. or beginning of the XIIth century a. The history of the kingdom is divided into two major periods: the Old Kingdom (beginning with the reign of Labarna) and the New Kingdom (beginning with the reign of Tudhaliya I/II). Other divisions adapt the history of the Hittites to the scheme of the historiography of the kingdoms of the Ancient Near East and establish three periods: old, middle and new. However, in this case, there is no unity to define when one ends and the next begins.

Origins

The origin of the Hittites and their "relatives" Luwites and Palaites—all speakers of Indo-European languages—who settled in Anatolia in the second millennium BC. C., is the subject of a debate that is linked to the origins of the Indo-European peoples. One hypothesis proposes an autochthonous origin, so that the Hittites were an indigenous people of Anatolia. However, the prevailing opinion is that the origin of the Indo-Europeans is in the steppes of southern Russia from which the Hittites migrated: they crossed the Balkans, crossed the straits that separate Asia from Europe and settled in Central Anatolia. Current knowledge does not allow it to be determined whether the Hittites, Luwites, and Palaites arrived in successive waves or at the same time, or whether perhaps a people who would be their common ancestor split into several groups after their arrival in Anatolia. The dating of these migrations remains controversial, with some scholars proposing periods as far back as the third millennium BC. C.

Early Kingdoms

Whatever their origin, the earliest known Hittite texts are identified at the beginning of the second millennium BCE. C. in the archives of the Assyrian merchants of Central Anatolia where they established several commercial colonies. The most important was the one located in Kanes (present-day Kültepe) where most of the tablets have been found. His study revealed the presence of various principalities that shared Central Anatolia in the XIX a. C.: to the north were Hatti (around Hattusa) and Zalpa (near the Black Sea); to the south, Buruskhattum (the Puruskhanda of later Hittite texts, perhaps present-day Acemhöyük), Wahsusana, Mama, and especially Kanes, in a region where the Hittites were most concentrated. The importance of the latter city for Hittite origins is reflected in that it is from his name that the Hittites called their own language (nesili, the language of Nesa, another name for the city of Kanes).

The first 'Hittite' dynasty to exercise hegemony in Central Anatolia comes from the city of Kussara - whose location is unknown - under the leadership of two kings of the century XIX a. C.: Pitkhana and Anitta. They established their capital at Kanes and subdued the major Anatolian states, including Buruskhattum, Hatti and Zalpa. This dynasty did not outlive Anitta for many years and disappeared under unknown circumstances.

The appearance of the great Hittite kingdom

The great Hittite Kingdom, whose dynasty uninterruptedly dominated much of the Anatolian peninsula for more than four centuries, was formed in the last decades of the century XIX a. C. Its founders were probably related to the Kussara dynasty. The nature of the connection is still obscure. The founder of the dynasty seems to have been named Labarna. This name was later used to refer to the monarch, in the same way that the names Caesar and Augustus were used to designate the highest offices of the Roman Empire.

The first king whose deeds are known is Hattusili I, successor to Labarna and a Hittite model of a conquering king. He established his capital in Hattusa and provided the first period of territorial expansion for the Hittite kingdom by seizing cities in northern Anatolia (Zalpa) and, above all, in the south, since he managed to threaten the positions of Yamhad (Aleppo), the most powerful kingdom in Syria in those days.

His grandson and successor, Mursili I, continued this warfare by finally capturing Aleppo and successfully raiding as far as Babylon in 1595 BCE. C. He thus caused the fall of the two most important kingdoms of the time in the Ancient Near East, but they were ephemeral successes.He was assassinated by Hantili I, his own brother-in-law, after his return from the expedition Babylonian. This was the prelude to a period of court intrigues and border disturbances that led the Hittites to progressive territorial withdrawal.

The instability of the kingdom

Mursili I's successors failed to stabilize the royal court, regularly rocked by bloody intrigues for much of the 16th century to. C. The situation was restored by Telepinu through the proclamation of an edict in which he prescribed the succession rules of the kingdom -in order to avoid more bloodshed- and to instruct his subjects in the rules of good administration of the State. In foreign policy he signed a peace treaty with the Kingdom of Kizzuwadna, bordering northern Syria, which became the dominant power in southeastern Anatolia.

Succeeding kings strove to maintain peaceful relations with Kizzuwadna, but he swung into the orbit of the new dominant power in Syria: the Hurrian-ruled Kingdom of Mitanni, which became a rival to the Hittites for hegemony on the kingdoms of Eastern Anatolia. At the same time a threat arose from the north where the Kaska tribes occupied the Pontic mountains and led devastating raids into the Hatti heartland. Courtly intrigues continued until the end of the 15th century BC. C. when Tudhaliya I/II ascends the throne.

The chronology of this period—sometimes called the Middle Kingdom—is poorly established, and the number of rulers on the throne is still debated. Regardless, the kingdom was strengthened against its opponents. The threat of the Kaskas was contained by establishing a border area dotted with garrisons, some of which are well known from excavations and unearthed tablets (at Tapikka, Sapinuwa, Sarissa). To the south, the Kingdom of Mitanni was in trouble during this period by the Egyptian offensive that reached its southern border. Kizzuwadna left its orbit to return to the alliance with the Hittites. Other conflicts drive the Hittite kings to western Anatolia, where the rise of the Arzawa countries threatened Hittite hegemony in the region.

The reigns of Arnuwanda I and Tudhaliya III, during the first half of the XIV century B.C. In the north, the Kaskas stormed several strongholds before taking and sacking Hattusa, forcing the royal court to retreat to Samuha. In the west, the Hittites failed to permanently establish their authority and receded over time; meanwhile, the king of Arzawa sought recognition as a "great king" —which placed him on equal rank with the Hittite king— from Pharaoh Amenhotep III, as can be seen from the diplomatic correspondence of the Amarna letters. In the east, the kingdoms of Isuwa and Azzi-Hayasa threatened the Hittites. In the middle of the XIV century B.C. C. the great powers of the Ancient Near East seemed to be witnessing the end of the kingdom of the Hittites.

The Hittite Empire

Tudhaliya III appointed a prince of the same name, known as Tudhaliya the Younger, as heir. He was supplanted by Suppiluliuma I (c.1350-1322 BCE) , probably his half-brother. Suppiluliuma I was a military leader of great courage who undertook the first efforts to recover the Hittite kingdom from the catastrophic situation in which he found himself. He recaptured Arzawa and Isuwa and established the vassalage of Azzi-Hayasa. His most notable successes took place in Syria where he considerably extended his influence after inflicting two severe defeats on Mitanni, later sunk by succession intrigues. Syrian vassals of Mitanni rebelled against Hittite influence in the region, but were subdued and placed under the tutelage of Hittite viceroys. The capitals of these viceroyalties were Aleppo and Karkemish. Before starting an open conflict against Egypt, he attracted the loyalty of some vassals of Pharaoh Akhenaten such as Ugarit, Qadesh or Amurru. However, the prisoners deported to Hatti during the first clashes brought a plague epidemic that had, as its best-known victims, Suppiluliuma I himself and his successor Arnuwanda II.

The young Mursili II (c.1321-1295 BC) seized power under difficult circumstances. However, he had unparalleled military ability at the time that allowed him to complete the work of his father, Suppiluliuma I, by subduing the Arzawa countries and handing them over to various faithful vassals. He fought against the kaskas. Several vassal rulers of his father, both in Anatolia and Syria, rebelled against his authority, but were defeated. In the case of the Syrians, it was possible thanks to the actions of the viceroys of Karchemish, established as intermediaries of the authority of the great king.

Vassal revolts and the fight against Egypt, given a new impetus under the early 19th Dynasty kings, were the main military concerns of Muwatalli II (h.1295-1272 BC), the next king. The clash against Egypt occurred in the battle of Qadesh (h.1274 BC) where his troops and those of Ramses II will leave without a decisive victory for either side.

Muwatalli II's designated successor is his son Urhi-Tesub who ascended the throne as Mursili III (c.1272-1267 BC). His mother was a concubine, not the titular queen, so his legitimacy was undermined. His uncle, Hattusili III, a brilliant leader who distinguished himself in the war against the Kaskas, overshadowed him. The power struggle that ensued between the two sides favored Hattusili III (c.1267-1237 BC), who banished his nephew. Hattusili III's reign was marked by the desire to recognize his full legitimacy in the eyes of the other kings. He managed to conclude peace with Ramses II, who married two of the Hittite's daughters. The most formidable opponent for the Hittites during his reign was Assyria, which arose from the spoils of Mitanni and brought Upper Mesopotamia as far as the Euphrates under its rule.

The next king, Tudhaliya IV (c.1237-1209 BC), reigned with the support of his mother, the influential Puduhepa. He suffered a heavy defeat from Assyria, although it did not threaten his position in Syria as Tudhaliya IV held the Karchemish viceroyalty. The situation was more turbulent in Western Anatolia at the time that the kingdom of Alasiya (island of Cyprus) was subdued. The ruling dynasty saw its legitimacy questioned by the presence of a collateral branch of the royal family installed in Tarhuntassa, run by another secondary son of Muwatalli II, Kurunta, and his successors. Kurunta seems to have seized the Hittite throne. If so, he was displaced by Tudhaliya IV soon after. The reigns of Hattusili III and Tudhaliya IV were also marked by the embellishment of the capital Hattusa, abandoned by Muwatalli II, and by the cultural reform that led to a greater presence of Hurrian elements in the official religion, illustrated by the remodeling of the rock sanctuary of Yazilikaya.

The collapse of the Hittite kingdom and its vassal states

Arnuwanda III and later Suppiluliuma II succeeded Tudhaliya IV. Hattusili III's line of succession was maintained as the collateral branches of Karkemish and Tarhuntassa consolidated, perhaps contributing to a play of centrifugal forces that gradually weakened Hittite power. In this period, the main external threats appeared in western Anatolia and in the Mediterranean coastal regions where population groups arose that the Egyptians called Peoples of the Sea. The sources do not allow restoring a clear image of this period, but it is clear that the first years of the XII century a. C. saw the Hittite state overwhelmed by these new threats. Other factors may have contributed to the crisis, such as the persistent famine in Central Anatolia. Most of the Anatolian and Syrian sites from this period show signs of violent destruction. Hattusa was abandoned by the royal court before being destroyed. The fate of the last known Hittite king, Suppilulliuma II, is unknown. Those responsible for the destruction on the coasts of Syria seem to have been the Peoples of the Sea, but for the inland regions uncertainty continues to exist. The destruction of Hattusa is attributed to the Kaskas or the Phrygians who took over the place soon after. The descendants of the Hittite royal dynasty established in Karkemish and Arslantepe (modern Malatya) survived the collapse of the great kingdom and ensured the continuity of Hittite royal traditions.

The Neo-Hittite Kingdoms

The cultural and political landscape of Anatolia and Syria was highly turbulent during the late second millennium BCE. C. and the beginning of the next. The Hittite language stopped being spoken. The kingdoms that succeeded the great Hittite kingdom retained for official inscriptions the use of Hittite hieroglyphics which they actually transcribed in Luwian. The former country of Hatti was occupied by the Phrygians, a newly arrived people, who can perhaps be identified with the mushki mentioned in Assyrian texts. The latter still used the term Hatti to refer to the kingdoms established in Syria and southeastern Anatolia that modern scholarship calls Neo-Hittites because they continued Hittite traditions while crafting an original culture of their own.

The Neo-Hittite kingdoms were represented by the two branches descending from the Hittite kings established in Karkemish and Arlanstepe, as well as other dynasties in Gurgum, Kummuhu, Que, Unqi or in Tabal and even Aleppo. Most of Syria, however, remained under the control of a new Semitic group that emerged during this period of crisis: the Aramaeans, established in Samal, Arpad, Hamat, Damascus or Til Barsip. Therefore, the Neo-Hittite and Aramaic kingdoms should be considered a cultural and political mosaic that combines Aramaic and Luwian elements, among others. These states clashed from the IX century BC. C. to the expansion of the mighty Assyria to which they tried to resist requesting the help of Urartu, a new state that emerged in Eastern Anatolia. They were eventually overtaken and annexed to the Assyrian Empire during the second half of the VIII century BCE. C.

Foreign relations

Sphere of influence: vassals, viceroys and vassalage treaties

In addition to the territories directly administered by the Hittites, there were states subject to their authority that had their own administration. His sovereignty had to be approved by the Hittite king, who reserved the right to intervene in his business. Despite this, most vassals possessed considerable autonomy. In Anatolia, the main Hittite vassals were the countries of Arzawa (Mira-Kuwaliya, Hapalla, the country of the Seha River), Wilusa and Lukka (classical Lycia) to the west; Kizzuwadna and Tarhuntassa to the south; Azzi-Hayasa and Isuwa to the east; and, during certain periods, the kaskas to the north. In Syria, after the reign of Suppiluliuma I, the Hittites had several vassal states: Aleppo, Karkemish, Ugarit, Alalakh, Emar, Nuhasse, Qadesh, Amurru and Mitanni among the main ones. Among these kingdoms, some had a particular status because they had been given to members of the Hittite royal dynasty: Aleppo, Karkemish, and Tarhuntassa had their own collateral dynasties; others, such as Hakpis, entrusted to Hattusili III before his accession to the throne, only gained that status temporarily. The Karchemish Hittite dynasty played a special role during the last years of the kingdom. Their sovereign intervened in the affairs of other Syrian states to resolve disputes, a task that normally fell to the Hittite kings, but which they delegated to their viceroys to lighten their burden of tasks.

The relations between the Hittite kings and viceroys and their vassals are well reflected in the archives discovered in the excavations of Ugarit and Emar. The Hittite authorities had to resolve disputes between their vassals to guarantee peace and cohesion in Syria —border, marriage, and trade problems—, fix tributes, and supervise surveillance of possible external threats. Several decrees were issued to resolve such cases. The Ugarit and Emar texts show other representatives of the Hittite power—who are part of the "king's sons" group, the Hittite elite—sent near the vassals.

To formalize relations with their vassals, the Hittites had the custom of granting treaties (in Hittite, ishiul- and lingais-; in Akkadian, RIKSU/RIKILTU and MAMĪTU) and put them in writing, similar to other instructions intended for other servants of the kingdom. Several dozen of these treaties have been found in Hattusa in the area of the palace or in the great temple, where they were filed close to the divinities that guaranteed them. They maintain a stable model during the imperial period: a preamble in which the contracting parties are introduced followed by a historical prologue that reconstructs the past relations between them and justifies the vassalage agreement; Next, the obligations of the vassal are stipulated—generally, the requirement of loyalty to the Hittite king, the obligation to extradite people fleeing Hatti, some military obligations such as participating in military campaigns alongside the king or the protection of the Hittite garrisons and, sometimes, the fixing of the tribute to be paid or the regulation of border conflicts—; the final parts prescribe the number of copies of the treaty and, sometimes, the need to write on metal tablets (silver or bronze) and the places where it was to be deposited (palaces and temples); follows a list of the gods that guarantee the agreement and, finally, the last words are curses against the vassal who violates the treaty. Some vassals had a higher honorary status than others and established treaties called kuirwana, which are formally treaties between equals, because these vassals were descendants of kings of states that in the past were equal to Hatti: Kizzuwadna, before incorporation into the kingdom, and Mitanni.

The Hittite king and his "brothers"

Since the time of Anitta and Hattusili I, the Hittite kings took and saw recognized the title of «great king» (in Akkadian, šarru rābu, the diplomatic language of the time) that placed them in the very closed club of the dominant powers of the Ancient Near East. This rank was recognized in principle to the kings who had no lord, who had a powerful army and numerous vassals. They recognized each other as "brothers," except when relations between them were especially bad. They were, in addition to the Hittite kings, those of Babylon, those of Egypt and, in successive periods, those of Aleppo, Mitanni, Assyria, Alasiya (despite their low strength) and Ahhiyawa.

Diplomatic relations between the great kings of the second half of the second millennium BC. C. are known from the Amarna letters unearthed in the ruins of the ancient capital of Pharaoh Akhenaten and the correspondence of various Hittite kings found at Hattusa.

The exchange of messages was done through messenger ambassadors because there were no permanent embassies. However, some envoys might specialize in dealing with a particular court and stay there for months or years. These missives were generally accompanied by an exchange of gifts in accordance with the principle of donation and counter-donation. If the messages concerned political matters, many dealt with the relations between the sovereigns, who were the object of tensions related to the prestige between equals that they could lose —particularly regarding the magnificence and value of the gifts received or sent—, or of the marriage alliances that united them. Hittite kings married Babylonian princesses several times, as they were long allied with the Cassite dynasty that then ruled the Mesopotamian kingdom. Hattusili III, for his part, sent two of his daughters to marry Ramesses II. This reinforced the alliance between both courts and was the subject of long negotiations. International treaties concluded between great kings were also the subject of extensive negotiations. The only well-known case was a treaty between Hattusili III and Ramesses II.

War and the army for the Hittites

War was very present in all Hittite history, to the point that it is difficult to find an ideology of peace in the texts. The ideal state seems to have been the absence of internal conflicts in the kingdom and specifically in the royal court, potentially very destabilizing and destructive, rather than confrontation with external enemies that appear to be normal. The warfare was seen as the recreation of a divine trial —ordeal— in which the future winner had the divine powers on his side. A text describes a ritual that the sovereign had to perform before a campaign to begin it with good omens. On the other hand, the Hittite king is never presented as the instigator of the conflict, but always as the attacked one who had to react to restore order.

When he won the conflict, the Hittite king established formal relations with the defeated by entering into a written treaty, instead of relying on terror, which was supposed to guarantee stability in the region. This did not prevent that the war continued with destruction, looting and other looting as well as the deportation of prisoners of war and therefore it was a way of hoarding wealth.

The Hittite army was under the supreme command of the king, who was at the center of a network of advisers who informed him of all active and potential military fronts in the empire. This information was based on border garrisons and espionage practices. The king could lead his troops or delegate a general, especially when there were several simultaneous conflicts. This was a privilege of the princes —in the first place of the king's brothers (the head of the royal guard, MEŠEDI) and the eldest son—, of the high dignitaries such as the great steward and, each and more over time, of the viceroys, especially that of Karkemish. The lower rank was made up of the commanders of the different troop corps (wagons, cavalry and infantry), positions that were divided between a chief of the right and a chief of the left. Other important officers were the chiefs of the guard tower and the supervisors of the military heralds, who took care of the garrisons —mainly the border ones—, and could command the army corps. The military hierarchy descended from here to the officers who led the smaller units.

The heart of the army was made up of permanent troops stationed in garrisons. They were sustained by supplies collected from state stores and, perhaps also, from service land grants. According to the needs of certain conflicts, forced levies of troops were made among the population and the vassal kings had to provide fighters. In addition to the texts of instructions for the MEŠEDI and the chiefs of the guard tower, They know of other texts intended to guarantee the competence and, above all, the loyalty of the soldiers. There are instructions to officers, written down to ensure the reliability of those leading the troops, and a ritual of the military oath that soldiers and officers had to take when they entered service, swearing allegiance to the king and describing in detail a similar ritual of curses to which they were exposed in case of desertion or treason (acts that were, in any case, punishable by the death penalty).

Most of the troops in the Hittite army were infantry, equipped with short swords, spears, and bows, as well as shields. Contrary to popular belief, the metal for Hittite weapons was bronze, not iron. The infantry accompanied the elite troops, the chariots, known from Egyptian reenactments of the Battle of Qadesh showing their ability to launch a rapid offensive. Pulled by two horses, these chariots were usually ridden by a driver and a combatant armed with a bow, but in Qadesh performances they are accompanied by a third man carrying a shield. The cavalry was underdeveloped and served perhaps mainly for surveillance missions and express mail. According to Egyptian texts describing the Battle of Qadesh, the Hittite troops mobilized at that time—the height of the empire—numbered 47,000 soldiers and 7,000 horses, counting the troops of the vassals. However, the reliability of these figures has been questioned. During the later phase of the kingdom, they were also able to mobilize naval forces—particularly for the invasion of Alasiya—thanks to the ships of their coastal vassal states such as the kingdom of Ugarit.

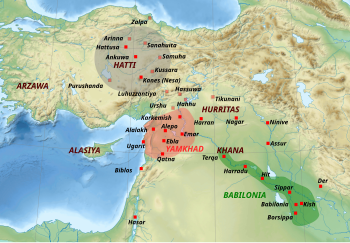

Geography

The heart of the Hittite Empire —commonly called Hatti Country— was located at the bend of the Kizil Irmak river (Marrasantiya in the Hittite language), where the capital Hattusa was located. This core bordered on the north with the Kaska tribes, on the south with Kizzuwadna, on the east with Mitanni and on the west with Arzawa. At the time of maximum Hittite expansion, Kizzuwadna, Arzawa and an important part of the Gasgan territory were incorporated into the Empire, which also included a good part (or all) of Cyprus and various territories in Syria, where the Hittite Kingdom limited the east with Assyria and south with Egypt.

Some major Hittite cities have been located, including Nesa and the capital Hattusa. There are still cities to find, such as Kussara, Nerik or Tarhuntassa. In Syria there were especially the cities conquered from the former Kingdom of Iamhan of Aleppo, Karchemish and Qadesh.

Culture

It is very probable that from graphisms, the Hittites would have come to develop their own script based mainly on pictograms, but although pictographs are found in the Hittite area, it is still not viable to relate them directly to Hittite culture nor is it possible for the moment qualify them as a systematized writing.

What is corroborable is that the Hittites adopted the cuneiform script used from the Sumerians. This script served them for their international trade, although it could be "dialectized" according to the Hittite language, although when used to a large extent in a way close to that of ideograms it was intelligible to neighboring allophone peoples.

The Hittite art that has come down to our days has been described since the time of the classical Greeks as a «cyclopean art» due to the magnitude of its stalls and the dimensions and relative coarseness of its bas-reliefs and a few bulk sculptures. These few bulk sculptures seem to have received some Egyptian influence, while the bas-reliefs show Mesopotamian influences, albeit with a typical Hittite style characterized by the absence of formal delicacies.

However, the most typical Hittite art can be seen in the few metallic elements (especially iron) that have survived to this day. Here one can also notice a "rude" and coarse art, although very suggestive due to a certain stylization and abstraction of a religious nature, in which quite cryptic symbols abound.

Hittite language

The Hittite language, also called Nesite, is the most important of the extinct Anatolian branch of Indo-European languages, the other members being Luwian (especially hieroglyphic Luwian), Palaic, Lydian, and Lycian. One of the great achievements of archeology and linguistics is having deciphered this extinct language, which is considered the oldest of all documented Indo-European languages. Precisely, being the oldest, it is interesting because of the elements it lacks and which are present in later documented languages.

One of its main characteristics is the large number of non-Indo-European words it contains, due to the influence of Near Eastern cultures, such as the Hurrian or the culture of the Hatti people, this influence being especially pronounced in the words of origin religious. It consists of most of the usual cases in an Indo-European language, two grammatical genders (common and neuter) and two numbers (singular and plural), as well as various verbal forms.

Although the Hittites appear to have had a system of pictographs, they soon began to use the cuneiform system as well.

Religion and mythology

An abundant pantheon

The Hittite religion became known as "the religion of a thousand gods." It had numerous divinities of its own and others imported from other cultures (especially from the Hurrian culture), among which stood out Tesub, the god of thunder and rain, whose emblem was a double-edged bronze ax (something similar, Although it may be coincidental, it is observed in the Minoan civilization, with its labrix), and Arinna, the goddess of the sun. Other important gods were Aserdus (goddess of fertility), Naranna, goddess of pleasure and birth and her husband Elkunirsa (creator of the universe) and Sausga (Hittite equivalent of Ishtar).

Temples, worship and celebrations

The king was treated as a human chosen by the gods and was in charge of the most important religious rituals, as well as safeguarding traditions. If something went wrong in the country, he could be blamed if he had made the slightest mistake during one of those rituals, and even the kings themselves shared this belief; Thus, for example, Mursili II attributed a great plague that devastated the Hittite kingdom to the murders that brought his father to the throne, and he carried out numerous acts and mortifications to ask for forgiveness before the gods.

Magic rituals

From numerous Hittite tablets, we know about magical rituals that aim to manipulate reality to summon and influence invisible forces (gods and others). These processes were used in a wide variety of cases: during rites of passage (birth, coming of age, death); during the establishment of bonds guaranteed by divine forces (engagement with the army, diplomatic agreements); to cure or expiate the various ills, to which a supernatural origin was attributed (diseases or epidemics that have their origin in a committed offense, spells due to the malice of a sorcerer or, more often, a witch, but also fights of partner, sexual impotence, a military defeat, etc.).

These rituals mobilized many specialists. In the first place to the «old women» (sumerogram, ŠU.GI; in Hittite, hassawa), who seem to have been the experts in rituals par excellence, but also to divination specialists, who completed their usual practices through magical rituals, and exorcist doctors (A.ZU, which could be translated as "physicist"). Indeed, Hittite medical practices combined remedies that to modern eyes would reveal scientific medicine with others that were of a magical order. This difference was not appreciated by people in ancient times.

The magical rituals of the Hittites could follow several rules:

- La analogy or sympathy which consisted of the use of objects with which activities were carried out that symbolized the effect of what they wanted to achieve, while reciting enchantments that guarantee their effectiveness. For example, during the ritual of entry into service of the soldiers, the wax was crushed to symbolize what would happen to them in the event of desertion; during the ritual against sexual impotence, the man gave in the ritual a huso and a rueca, which represented femininity (assimilated to impotence), and they found him a bow and arrows that symbolized the virility.

- The Contact It ensured the transfer of an evil from a person or object to another object or parts of a sacrificial animal. This was done only by touching or stirring the object that was supposed to capture the evil around the treated person; or by passing the latter between the parts of objects and animals that constituted a sort of symbolic portal that would allow to dispel the evil when it was crossed.

- La replacement It was a process that allowed to replace the person receiving evil by an object (often a clay figurine that represented it), an animal or even another person in the case of kings. The substitute was later destroyed, sacrificed or exiled (practice of the scapegoat) carrying with it evil.

Divination

The will of the gods was accessible to men through divination. This allowed the Hittites to know the origin of a disease or an epidemic, of a military defeat or of any evil. The information collected in this way should then allow the execution of the appropriate rituals. Divination could also be used to judge the timing of an action they wanted to perform (start a battle, build a building, etc.) in anticipation of whether they had divine consent, whether it would be performed at an auspicious or harmful moment, and, above all,, to know what was going to happen in the future.

There were various types of divination practices. Divination through dreams (oneiromancy), which seems to have been the most common, could be of two types: either the god addressed the sleeper himself, or he caused sleep (incubation). Astrology is attested in texts found in Hattusa. The other most common oracular divination procedures were reading the entrails of sheep (hepatoscopy), observing the flight of certain birds (augurs), the movements of a water snake in a basin, and an enigmatic process consisting of casting lots. objects that symbolized something (life, well-being of a person) supposedly to reveal the future.

Therefore, divination could be produced in men with the precise rituals, or it could emanate directly from the gods spontaneously and be imposed on the men who would then have to interpret the message. In all cases it was necessary to appeal to divination specialists. Some were specialized in certain specific practices, such as the BARU in hepatoscopy or the MUŠEN.DÙ for the interpretation of dreams. The "old woman" also performed many of these rituals.

Myths

A number of mythological tales have been unearthed in the ruins of Hattusa. The fragmentary state of most of them makes it impossible to know their outcome or even their main development. However, some pieces are among the most notable in Ancient Near Eastern mythology. Most of these myths do not have a Hittite origin: many seem to have a Hattian background; others have a Hurrian origin (perhaps more precisely from Kizzuwadna).

Among the myths of the first group, a recurring theme is that of the disappeared god, the best-known example of which is the myth of Telepinu. The eponymous god disappears, endangering the prosperity of the country, of which he was the guarantor. Barrenness strikes fields and animals; the water sources dry up; hunger and disorder reign. The gods investigate how to bring Telepinu back, but fail before a little bee sent by Hannahanna manages to find him and wake him up. The end of the text is lost, but it is evident that the return of the god and prosperity were narrated in it. Other myths are known that narrate the disappearance of other gods and that follow this same pattern. They refer to the moon god in the myth of the moon that fell from the sky, various storm gods such as Nerik, the sun god and many more. They are often only known from fragmentary stories or from the rituals in which the development of the myth is reproduced and which allow the return of the god and thus ensure the prosperity of the country. These myths are clearly related to the agricultural cycle and the return of spring. They symbolize the return of order in the face of disorganization, which can be guaranteed by applying the myths linked to it.

Another important Anatolian myth is that of Illuyanka. It is known by two versions and recounts the combat of the god of the storm against the gigantic serpent Illuyanka. The great god's victory comes despite initial setbacks and with the help of other gods. This myth falls within the theme of myths that have a sovereign deity confronting a monster that symbolizes chaos—as in the Baal cycle of Ugarit, the Babylonian creation epic. Like the latter, it was recited and perhaps performed during one of the great spring celebrations (the purulli celebration among the Hittites).

The last great myth, known from some Hattusa tablets, is the Kumarbi cycle, a myth of Hurrian origin divided into five unequally known «songs» (Sìr). Its theme is the declaration of the god Tesub (the Hurrian god of the storm) before several adversaries, in the first place Kumarbi who supplants him in the first story: Kumarbi's song. The rivalry between the two ends in Ullikumi's song in which Tesub must defeat a giant spawned by his mortal enemy. This mythic cycle is more general in scope than the preceding ones because it begins with a narrative of the origin of the gods and explains the creation of their hierarchy and, in particular, the primacy of the storm god. It is also the one that presents the greatest parallels with Greek mythology, since the narration of the generational conflicts of the gods is very close to that of Hesiod's Theogony.

Of the Hittite myths that have come down to us, we have humans as main characters, but also involving the gods. The myth of Appu tells the story of a wealthy childless couple who implores the Sun god to come to his aid. This ultimately allows them to have twins, one good and one bad, who will later become rivals following a pattern known in other ancient cultures (such as Cain and Abel in the Bible). The legend of Zalpa introduces a historiographical text that tells of the capture of this city by Hattusili I and undoubtedly serves to present the origin of the conflict. It recounts how the queen of Kanesh gives birth to thirty children that she pursues after her birth and who survive thanks to divine help to grow in Zalpa. Later, they are about to join the thirty daughters the Queen of Kanesh had borne next, at which point the story stops.

Death and the afterlife

Following the concepts that appear in several texts found in what was the country of Hatti, the Hittites divided the universe into Heaven —the upper world where the great gods lived— and a group formed by Earth and Hell — the subterranean world described as "dark land" -, to which the deceased arrived after death. It was accessible from the earth's surface through the natural cavities that lead into the depths: wells, swamps, waterfalls, grottoes and other holes (such as the two chambers of Nişantepe in Hattusa). These places could serve as spaces for rituals related to infernal deities. As its name suggests, the gloomy land was seen as an uninviting world where the dead led a grim existence.

Hittite texts appear to be heavily influenced by Mesopotamian beliefs in the afterlife, making it difficult to determine to what extent they reflect local folk beliefs. Like the inhabitants of the country of the two rivers, the Hittites placed the underworld under the protection of the Sun Goddess of Earth (the Sun Goddess of Arinna) who collects aspects of the ancient hatti goddess Wurusemu. She is associated with Lelwani, another great Hatti infernal divinity, and assimilated with her Sumerian and Hurrian equivalents Ereshkigal and Allani. The Anatolian infernal world was populated by other gods, servants of this queen of hell, in particular by some goddesses who spun the lives of men just like the moiras of Greek mythology or the Fates of Roman mythology.

Known funerary practices are mainly those concerning kings and members of the royal family who benefited from lavish funerals and the ancient cult of the dead. No royal tombs have been discovered. The sovereigns and their families were cremated and their remains were undoubtedly deposited in their funerary place of worship called hekur. Perhaps we have an example with chamber B of Yazilikaya, which would then have served for the funerary cult of Tudhaliya IV and whose bas-reliefs could represent infernal divinities. Regular sacrifices were offered to deceased kings and members of the royal family, and their mortuary temples were rich institutions endowed with land and staff, as in the great temples. This practice of ancestor worship probably existed among the people as well, with the to ensure that the dead did not return to haunt the living in the form of ghosts (GIDIM). If necessary, they could be expelled through exorcisms.

Anatolian cemeteries from the second millennium BC date mainly to the first half of this period, corresponding to the time of the Assyrian merchant colonies and the ancient Hittite kingdom. Few cemeteries from the period of the Hittite Empire have been brought to light. The most important is that of Osmankayasi located near Hattusa. These cemeteries document the burial practices of the lower and middle classes of Hittite society. Burial and cremation coexist, but the latter tends to increase over the course of the period. Burials could be made in cista tombs (certainly for the richest), in simple pits or in large jars called with the Greek word pithos (for the less wealthy). Most of the known tombs are located in necropolises, but some of them are found inside the city walls, below the residence of the deceased's family, as is also common in Syria and Mesopotamia.

Contenido relacionado

Halberd

Jean le Rond d'Alembert

Palencia