Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut, also known as Hatchepsut, was a queen-pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. The fifth ruler of said dynasty, she reigned from ca. 1513-1490 BCE C. She ruled under the name Maatkara Hatshepsut , and she became the longest-serving woman on the throne of the "Two Lands." She was the second historically confirmed female pharaoh after Sobekneferu.

Hatshepsut's name by which she is recognized today was originally a title meaning "First of Noble Ladies" or & #34;the chief lady of the nobility", who also presented herself in her full form as Hatshepsut Jenemetamun, that is, "The first of the noble ladies, united to Amun".

Hatshepsut was the only child of Thutmose I and his principal wife, Ahmose. Her husband Thutmose II was the son of Thutmose I and a secondary wife named Mutnefert, who bore the title of the king's daughter and was probably the daughter of Ahmose I. Hatshepsut and Thutmose II had a daughter named Neferura. After having her daughter, Hatshepsut was unable to have any more children. Tutmosis II with Isis, a secondary wife, would be the father of Tutmosis III, who would succeed Hatshepsut as pharaoh.

First Steps

Family

The exact moment of Hatshepsut's birth is unknown, although it is presumed that it happened in the then state capital, Thebes, at the end of the reign of Amenhotep I. Given the lack of descendants of the pharaoh, the designated successor was the Hatshepsut's father, the future Tutmosis I (Tutmose I), who in order to legitimize his imminent accession to the throne had had to marry Princess Ahmose.

This marriage brought into the world, apart from Hatshepsut, at least three other children, named Amenmose, Wadymose and Neferubity. Unfortunately, and due to the high rate of infant mortality, only Hatshepsut and her older sister, Neferubity (and this one only for a short time) would reach adulthood.

In addition to her siblings, Hatshepsut apparently had half-siblings on her father's side with secondary wives and concubines. The only record of which has come to us is that of her husband, Thutmosis II, son of Thutmosis I and a secondary wife, named Mutnefert.

Granddaughter, daughter and wife of pharaohs

Hatshepsut's father, Thutmosis I, had succeeded in expanding the Egyptian Empire in ways that had never been seen before in just thirteen years of his reign. This prodigious monarch would go down in history for leading his troops to the course of a huge river that, unlike the Nile, did not run from south to north, but vice versa: the Euphrates.

At the rather early death of Thutmose I, Hatshepsut was best placed to succeed him on the throne, as her male brothers were already dead. It is possible that even Thutmosis I himself tried while he was alive to associate her daughter to her throne, as evidenced by the fact that he named her Heiress . However, his wishes were not fulfilled, because apparently a palace conspiracy headed by the chaty and royal architect, the powerful Ineni managed to seat Tuthmosis II, born of a secondary wife, on the throne. Hatshepsut had to endure becoming the Great Royal Wife of her half-brother, and it is believed that this was a severe blow to her pride.

The young queen was a direct descendant of the great pharaohs who liberated the Hyksos and also held the very important title of God's Wife, which made her a bearer of the sacred blood of Queen Ahmose-Nefertari. It is logical that her pride was immense, and that she did not bear the idea of submitting to her husband very well. Thus, it is not surprising that while her weak and soft husband wore the double crown, Hatshepsut began to surround herself with a circle of followers who did not stop growing in power and influence: among them we especially highlight Hapuseneb and Senenmut. The great royal wife had become, to the fear of the vizier Ineni, a dangerous opponent. He was very aggressive with his family.

The third of the Tuthmosis

Thutmosis II had a very brief reign, dying in his youth when his only two known children were still in infancy. As had happened in the previous generation, the great royal wife Hatshepsut had not brought into the world a boy, but a girl, so a succession crisis began again. Once again, Ineni got the nobility to accept as the only feasible candidate a son of Thutmosis II and a simple concubine, who would be named king as Thutmosis III. However, the Dowager Queen Hatshepsut did not want history to repeat itself a second time, and the truth is that she modified it considerably.

Since Thutmose III was too small to rule, the great royal wife of Thutmose II assumed the regency and indefinitely postponed the marriage between the new king and his daughter, the princess royal Neferura, the only person who could legitimize his rise to power absolute. The situation was not rare, there were many cases of regency throughout Egyptian history, although never of a woman who was not the king's mother.

During the early years of Thutmosis III's reign, Hatshepsut was carefully preparing a "coup d'état" that would revolutionize the traditional Egyptian society. He removed Ineni from the political scene forever, and elevated his faithful Hapuseneb and Senenmut to the highest positions. It seems that the most important political figure of the time was Hapuseneb, who united for himself the positions of chaty and high priest of Amun. With such powerful allies, Hatshepsut now had the means and support to shock the world.

Hatshepsut, Pharaoh

Two pharaohs on the same throne

When she was strong enough, the until then great royal wife and wife of the god, Hatshepsut, in the presence of Pharaoh Thutmosis III, also proclaimed herself pharaoh of the Two Lands and firstborn of Amun, with the approval of the priests, headed by Hapuseneb. The coup d'état was masterful, and the inexperienced Thutmosis III could not do anything other than admit the superiority of his aunt and stepmother. Hatshepsut had become the third known queen-pharaoh in Egyptian history.

Hatshepsut assumed all the masculine attributes of her office except the title of "Almighty" making himself represented from then on as a man and wearing a false beard. He established an unusual co-regency with his nephew, although there was a very clear predominance of the first over the second, to the point of placing it in the background inappropriate for the future role that Thutmosis III would have in history. Such was the charisma and personality of this woman.

However, it is necessary to contextualize why we refer to Hatshepsut as pharaoh and not as queen-pharaoh or pharaoh. In ancient Egypt, the title of queen did not exist, since the sovereigns held, among others, the title of great royal wife and wife of the god, that is, the wife of the king. In no case can we refer to them as queens, since they lacked decision-making power and only had ritual functions. In fact, the closest title to queen in antiquity was Regent of the South and North, which alludes to unconfirmed temporal power.

Even so, Hatshepsut cannot be seen in any way as a usurper, a vision that some authors have transferred to our time. At least it was not seen that way in her time, because if it had been her case, Hatshepsut would have easily eliminated her adversaries or a civil war would have ensued. Thutmosis III was not locked up in the palace, as has come to be thought, nor did Hatshepsut avoid making any mention of her existence. The society of that time accepted the new situation without problems, and Hatshepsut enjoyed one of the most prosperous reigns in all of Egyptian history, thanks also to the support received by Hapuseneb and Senenmut.

Theogamy

Hatshepsut could not have even dreamed of accessing the throne without the support she gained among the clergy of the god Amun in Thebes while she was the wife of Thutmose II. The large donations and privileges that he granted to the priests, headed by the gray eminence of the regime, the vizier Hapuseneb, were a form of payment for the services rendered, for if it were not for the immense gift that Hatshepsut received from them, her legitimacy would have been less. And this valuable gift from the priestly caste to the queen-pharaoh was the famous Theogamy.

In Theogamy, Hatshepsut declares to the Egyptian people that their true father is not Thutmosis I, but the god Amun himself, who with his wise foresight visited the great royal wife Ahmose one night and allowed her to conceive the woman who was now sitting on the throne of the Two Lands with the approval of the entire pantheon. Hatshepsut therefore declared herself the firstborn of Amun, and her substitute and faithful delegate on earth, with which her figure became completely sacred.

It is necessary to highlight that very few pharaohs resorted to Theogamy to validate their right to the throne, and their status was little less than that of a living god. Hatshepsut's ruse and the high price she had to pay the priests for it, would ensure her a calm reign without dissent, although it would end up taking its toll on the dynasty ever since due to the increasingly growing and unstoppable influence of the priests of Amun..

Names

Like every king who acceded to the throne, Hatshepsut had the right to use up to five different names: Horus, Nebty, Horus of Oro, and the two main ones, commonly known as birth name and coronation name. The latter turned out to be that of Maat-Ka-Ra, that is, "The spirit of Ra is fair" and he always used it in conjunction with his birth name.

However, the latter name underwent a series of changes throughout Hatshepsut's reign. Although the original form of the birth name was Hatshepsut, in many monuments it appears in very different ways: adding the second part of the name and remaining as Hatshepsut-Jenemetamón, masculinizing it in partly as Hatshepsu or fully as Hashepsut. This is the only way to understand the surprise of the Egyptologists who discovered the existence of this woman who played in her apparitions, being represented as a man, with her names sometimes written such that she had been born a man or a woman. A curious game of exchanging the sexes that undoubtedly enhanced her divine character and concentrated in herself the duality that the Egyptian people so revered.

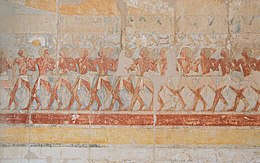

Iconographic representation

The iconographic representations of Hatshepsut have two important stages.

- First phase: In the first stage is represented Hatshepsut as a Pharaoh woman with her feminine body and with the typical headdresses of the Pharaohs such as the Nemes headdress, the skirt, the pharaonic pearl and the ureus but always with breasts, fine face and smiling slightly, in a stage was mostly represented in this form in statues and reliefs in closed spaces, this stage is taken into account from year V to VII of her reign.

- Second stage: In all the buildings and works (both sculptural and relief) in which it appears, Hatshepsut is represented in a masculine way, since the figure of the pharaoh could only be performed by a man, women had other kinds of functions and roles within the government such as that of Royal Bride and Great Wife of God. In the face of this situation, both to legitimize and to be accepted in spite of being a woman, she decides to represent herself in a male way, with the Nemes headdress, the faldellin, the edge and the characteristic ureus of the Pharaohs. On the other hand, he decides not to have offspring and to name his daughter Neferura Royal Bride and Great Wife of God, this stage takes place from the year VII until the end of his reign, Hatshepsut will be the first woman-faraon to be represented as a sphinx, as a Pharaoh or forehead and as the God of the underworld Osiris.

Building activity

Hatshepsut spent most of her reign beautifying the country and restoring the temples, with the blessing of her allies the priests. Egypt had suffered the last of its wars two generations ago, when the queen's grandfather, King Ahmose, drove out the Hyksos, a Semitic people who had managed to dominate the country for a hundred years. As her predecessors had done, Hatshepsut invested heavily in erasing all the damage caused by the war of liberation that had elevated his dynasty to the top.

He left his mark on the temple of Satet, on Elephantine Island, on the Speos Artemidos in honor of the goddess Pajet.

However, the queen's main center of action was her city, the thriving Thebes. He was involved in the enclosure of the sacred boats of Luxor, he built the so-called Red Chapel of the enormous temple of Amun in Karnak and, from the quarries of Aswan, he had the largest obelisks that had been erected in Egypt up to then made, and he took them to Karnak decorated with electrum, an alloy of gold and silver. The unfinished obelisk that can still be seen in Aswan today is believed to date from the reign of Hatshepsut, and if completed it would have been the largest in the country's history.

Although it was not in Karnak where Hatshepsut displayed all her imagery, but on the west bank of Thebes, the necropolis of that time. At that time, the pharaohs had built, in addition to his tomb, a mortuary temple somewhat away from it, which served at the same time to protect and remember the deceased. Hatshepsut chose the place of Deir el-Bahari to build her temple of millions of years, and entrusted the task to his favorite architect, Senenmut.

The final result was enviable, built next to the temple of Mentuhotep II, Hatshepsut's is one of the jewels of Ancient Egypt and one of the most visited destinations by tourists. Known at that time as the Dyeser-Dyeseru (the sublime of the sublime), its structure in the form of long terraces and gently sloping ramps, similar in style to that of Mentuhotep II, make it blend perfectly with the rock and the environment. One of the mysteries in this temple lies in a sector sealed like a box on the wall where Hatshepsut can be seen on one side in an attitude of love and Senenmut on the other side, as a recipient of the queen's love pose, which he deduces an intimate link (forbidden by his lineage) between the architect and the queen-pharaoh.

Military campaigns

Hatshepsut has gone down in history as a peaceful ruler who preferred to spend part of her treasure building temples instead of conquering territories, but the truth is that there were at least six campaigns during her 22-year reign. It should be noted that most of these did not go beyond mere skirmishes or deterrent activities whose sole purpose was to dissuade the always warlike border towns from attacking the Two Lands.

- First campaign. It was almost customary for a Pharaoh to die, the Nubian peoples attacked the southern borders and burned some of the fortresses of the place, as a tanteo of how the new monarch would react. Hatshepsut did not fall short and, although he was still only regent queen, he went to Nubia and led the attacks.

- Second campaign. In this case the enemies were tribes of Syria-Palestinian, whose continued attacks on the border posts made Egypt respond. The exact date of this war action is ignored, although it is very possible that it would happen when Hatshepsut had already been crowned. One thing that seems certain is that the queen did not travel to the front on this occasion.

- Third and fourth campaigns. The motive returns to Nubia. It is unknown why the Nubians were revolved so much in Hatshepsut, but the Egyptian troops were relentless. The third campaign was in the 12th and 4th year in the 20th, and both were solved without any problems. It is believed that Tutmosis III participated in the latter.

- Fifth campaign. Against the country of Mau, south of Nubia. It was immediately after the fourth campaign, perhaps due to a coalition of these two peoples. There are mentions of a rhinoceros hunt, and it is also likely that Tutmosis III would be in front of the army.

- Sixth campaign. Once again, Tutmosis III - anticipating his role as a warrior king that in his solo reign would eventually develop with excellent results- went to Palestine and conquered the city of Gaza, which had recently rebelled. The dates on this campaign date from the end of Hatshepsut's reign, perhaps immediately before the queen died. As you can see, his role was already merely representative, and Tutmosis III had become the dominant monarch of the curious real tandem.

The trip to Punt

Another relevant fact of Hatshepsut's reign was the double mission to Punt, the legendary country where the best frankincense and myrrh trees came from, which was probably in a region of present-day Somalia, approximately in the 15th year of her reign. Commanded by Nehesi, bearer of the royal seal, the expedition went both by land and by sea, and during it the Egyptian delegation not only engaged in trade, but also made a careful study of the fauna and flora of Punt, as well as of the political and social organization of the place.

This action must have been so important for Hatshepsut's position, that she did not hesitate to decorate a large part of the walls of the Dyeser-Dyeseru with scenes from that magical journey for which she would be remembered for a long time by the common people. Not only was it successful in importing the precious myrrh into Egypt, but it also brought in rare animal species never seen before and generous shipments of gold, ivory, ebony, and other precious woods that greatly enriched the royal and temple coffers.

Still, it is strange that Hatshepsut would go to such lengths to promote the trip to Punt, a country that had been known since the time of the pyramids, and can only be explained as one more part of the intense propaganda she distributed through the Dyeser -Dyeseru and other parts of the country with the sole purpose of legitimizing their position. Undoubtedly, by this time in his reign, with the inauguration of his beautiful temple and the return of the travelers from the Punt, Hatshepsut had reached the zenith of his rule.

Offspring

The only thing that is known for certain is that Hatshepsut was the mother of a daughter, whom she named Neferura and whose care she entrusted to her favorite architect, Senenmut. The true role of this man in the plot is unknown; there are not a few voices that say that he was the father of Neferura and not Thutmosis II, and that there was a torrid love story between the architect and royal chancellor and the queen, a story that despite being very interesting from the point of view fictional, remains unproven. In favor of all this there is some evidence, such as the fact that Senenmut and Neferura appear in a truly affectionate attitude, or an ostracon found near the temple of Deir el-Bahari where they were he sees a female pharaoh having sex with a man. Even so, although more and more voices are raised in favor of a romance between Hatshepsut and Senenmut, it is still thought that Neferura was the daughter of Thutmosis II.

There has also been much discussion about the possible motherhood of Meritra Hatshepsut, who would later be the great royal wife of Thutmosis III. Due to her name, she was always thought to be Hatshepsut's second daughter, but it was really strange that she was never mentioned to her during her presumed mother's lifetime, while Neferura appeared so often. Today it seems to have become clear that, despite bearing her name, Meritra Hatshepsut was actually the daughter of Lady Huy, a very influential woman at court at the time, and perhaps that nickname was meant to flatter the queen-pharaoh. Thus it could be understood why when Thutmosis III began to pursue the memory of his stepmother, his great royal wife chose to be called simply Meritra.

According to studies by the Cairo Museum, sponsored by the Discovery Channel and led by Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, Thutmose's offspring suffered from a variety of hereditary smallpox, from which no descendant escaped.

Disappearance

Death of Hatshepsut

However, it was after the completion of the Deir el-Bahari temple, around regnal year 15-16, that Hatshepsut's star began to wane in favor of Thutmose III's. The king was a young man who yearned more and more for power, and at any price. Thus, it is not surprising that in just one year the queen's two main supporters and her greatest supporters, Hapuseneb and Senenmut, died. And as if that were not enough, shortly after the great hope died, the queen's secret weapon, Princess Neferura.

The blows suffered by Hatshepsut around the 16th year of her reign were so great that from then on the queen partially withdrew from office and the other king, Thutmosis III, began to take the reins of government. Apparently Hatshepsut's ambition was even greater and she was not satisfied with being "pharaoh" on her own, but intended to inaugurate a true female dynasty of kings, and for that reason declared "Heir& #3. 4; to her beloved daughter Neferura. The death of the princess was so sudden and favorable to Thutmosis III that there are those who think that it was intentional, and that she achieved her objective, to overthrow the queen-pharaoh.

Hatshepsut died in her palace in Thebes after a long reign of 22 years, abandoned by all. The age of her death is unknown, but it is estimated that it should range between forty and fifty years. Years ago it was not known exactly how she died, whether it was a natural death or during a coup led by her stepson, Thutmosis III, who at that time was virtually the only king, since Hatshepsut had withdrawn from the fight.

According to National Geographic and archaeologist Zahi Hawass, the mummy was scanned and it was found that the queen had suffered in life from advanced osteoporosis and malignant cancer in the abdomen area that passed to her hip bone; In addition, she had contracted a septic abscess in her oral cavity that could have caused septic shock as a more probable cause of her death than an attempt on her life. According to these latest investigations, her death was preceded by long months of intense pain and fever.

His tomb is located in the Valley of the Kings and is listed as KV20. There are indications that he had her father's tomb enlarged to be used for her as well. The love and loyalty that her daughter professed to her father had to be so great that she wanted to stay with him forever.

Upon his death, Tutmosis III would become a great pharaoh who, emulating his grandfather Tutmosis I, carried out numerous campaigns and promoted Egypt to the rank of a great world power. But he would never have made it without the preparation his step-aunt put him through.

Hatshepsut's name and that of her faithful collaborator Senenmut were systematically erased from Egyptian annals and buildings, being victims of a "damnatio memoriae". For a long time it was believed that the late Tutmosis III had been the one who ordered the virtual "oblivion" of this energetic queen, but more and more Egyptologists support the theory that her name was erased for reasons of convenience rather than revenge. In Egypt there was a group of families identified with Hatshepsut, her family hers before marrying Thutmosis II. Upon the queen's death, Tuthmosis III may have erased his stepmother's name in order to legitimize his ascendancy to the throne, as royal heir to Tuthmosis II, and thus curb the claims of Hatshepsut's powerful family. This position is acquiring more and more strength, due to the archaeological evidence found in Deir el-Bahari. If there had been a revenge, her artistic and archaeological legacy would have been erased from Egypt. However, the queen was found in an excellent state of preservation with part of her grave goods.

The mummy of Queen Hatshepsut

In 2005 Zahi Hawass, director of the Egyptian Mummy Project and secretary general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, and his team focused on a mummy called KV60a, discovered more than a century earlier. At no time was this mummy believed to be important enough to be removed from the floor of a minor tomb in the Valley of the Kings as it was found without a coffin and without the treasures that distinguished the pharaohs, discovering many years later that it was the mummy of queen pharaoh.

Hatshepsut's mummy was unveiled to the public in June 2007, after a long period of uncertainty about its correct identification. Zahi Hawass, secretary general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Egypt, said that it was the most important archaeological discovery since the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen, in 1922.

Both mummies were discovered in tomb KV60 in the Valley of the Kings. This sepulcher was ordered to be built by Hatshepsut herself for her nurse, to whom she professed great affection, Lady Sitra. In it were found the bodies of a woman in her forties or fifties and an old woman over sixty, who had the peculiarity of having her left arm bent in the typical position of deceased queens. The discovery of the mummy prompted several questions: how did she get there, who was the lady in the sarcophagus, and why was the "real" mummy sore? she was on the ground

It is known that the mummy was found in the midst of a large number of linen canvases, naked, bald, obese, and with signs of having been moved from its original location. At first it was considered that the obese mummy was someone unimportant who did not deserve a large burial. When it was found, its discoverers paid no attention to the position of the arm, limiting themselves to writing about it that "she had enormous breasts that fell like pendulums." Afterwards, the discoverers of the KV60 limited themselves to tidying up the very messy tomb (according to them, there were many objects scattered all over the floor) and depositing the mummy in a new wooden coffin made in Cairo.

Much later, the identity of five unidentified female mummies began to be studied. One of those mummies was presumed to be that of Hatshepsut. Zahi Hawass ordered a CT scanner (donated by Siemens) to be brought to the Valley of the Kings, where high-resolution images of the mummies stored in KV60 were taken.

Before the identity of the mummy was verified, the mummified liver had already been discovered, which most certainly belonged to Hatshepsut. Next to the liver were the intestines and a molar with a single root; this piece was the key to its correct identification. The box of canopic jars was found in the cache of royal mummies DB320, which initially suggested that Hatshepsut's body would be one of those not identified in DB320.

A scan of the obese mummy's jaw revealed the absence of a molar piece, of which only a root remained. A forensic odontologist was immediately called in and determined that the root and tooth found in Hatshepsut's canopic jars were parts of the same tooth; both pieces matched perfectly. Based on this finding, the obese mummy was determined to be the body of Hatshepsut.

Hatshepsut in Literature

The interest that Hatshepsut has aroused in modern society is undeniable, and the positions regarding her that archaeologists, historians or simple readers have could not be more varied. Hatshepsut is currently turned into a Machiavellian usurper, into a political animal that does not back down in order to satisfy her ambition, into a woman who had to choose between love and her kingdom, into a lover of peace or a feminist model, or all this at the same time, depending on the person who thinks about it.

It is therefore not surprising that there is a wide range of books dedicated to Egypt, the New Kingdom or even to her altogether in which there are all possible points of view, and more. Nor is her presence missing in her novels, which usually paint her as a beautiful and ambitious woman who lived a life worth remembering, along with Thutmosis I, Tutmosis III or Senenmut, for some a pharaoh without a crown. Be that as it may, the charm emanating from Hatshepsut is indisputable, which can only be compared to that which surrounds other great figures of Egyptian civilization such as Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen, Ramses II or Cleopatra VII.

Degree

| Titulatura | Jeoglyphic | Transliteration (transcription) - translation - (references) |

| Name of Horus: |

| wsr t k)w (Useretkau) Powerful kas (spirits) (Deir el-Bahari) |

| Name of Nebty: |

| w) precursor t rnpwt (Uadyetrenput) Prosper years (Deir el-Bahari) |

| Name of Hor-Nub: |

| )w (Necheretjau) Divine appearance (Deir el-Bahari) |

| Name of Nesut-Bity: |

| (Maatkara) Just (Armonese) is the Ka (spirit) of Ra (Deir el-Bahari) |

| Name of Sa-Ra: |

| ḥ)t špswt (Hatshepsut) The first of the noble ladies |

| Name of Sa-Ra: |

| ḥ)t špswt ḥnmt θmn (Hatshepsut Jenemetamon) The first of the noble ladies. United to Amon |

Contenido relacionado

Algar

Stockholm

Napoleon (disambiguation)