Guatemalan history

The history of Guatemala is the chronology of events that occurred from the beginning of the first human settlement in the current territory of the Republic of Guatemala to the present day. This begins with the first groups of people to inhabit the region, of which the Mayan civilization stands out. The Spanish conquerors arrived in Guatemala in 1523. Nicolle Valle named the city of Guatemala, in her writing letter addressed to Carlos V, dated in Mexico on October 15, 1524. Cortés refers to "some cities that many days had I have news that they are called Ucatlán and Guatemala». The region became the General Captaincy of Guatemala, attached to the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

In the 19th century, the Creoles of the Captaincy General of Guatemala achieved their independence from the Spanish Empire and the region was renamed the Central American Federation, the which was annexed for a time to the empire of Agustín de Iturbide in Mexico. After the separation of Mexico, the wars began between the conservatives —that is, the Creoles with the highest ancestry and who lived in the federation's capital, also known as the Aycinena Clan, and the regular clergy of the Catholic Church— and the liberals, that they were creoles of a lower category that were dedicated to agriculture on a large scale and lived in the rest of the General Captaincy. The struggle led to the disintegration of the Central American Federation, from which emerged the five Central American republics, including present-day Guatemala.

A State of the Central American Federation governed by conservatives such as Mariano Aycinena and later by the liberal Mariano Gálvez, the modern Republic of Guatemala was founded on March 21, 1847, during the conservative government of General Rafael Carrera, and thus it began to have diplomatic and commercial relations with the rest of the nations of the world. Under Carrera's command, Guatemala resisted all invasion attempts by its liberal neighbors.

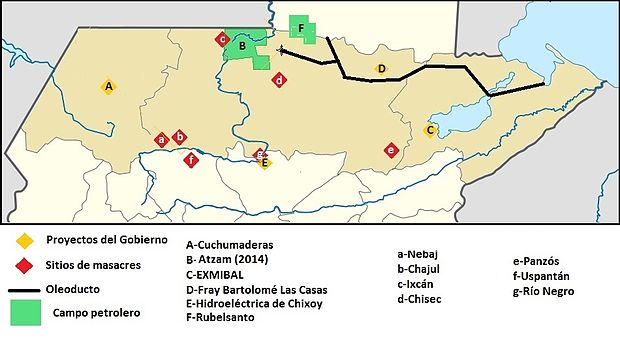

In 1871, six years after Carrera's death, the Liberal Reform triumphed and liberal regimes of a dictatorial nature were established. Coffee became the country's main crop. In 1901, during the government of lawyer Manuel Estrada Cabrera, the meddling in state affairs of North American corporations began, such as the United Fruit Company (UFCO), the main company in the country. Guatemala went on to become a banana Republic, where the rulers were placed or removed by the UFCO, depending on economic needs and from which it obtained considerable concessions. In 1944, in the midst of World War II, the October Revolution took place, which overthrew the then military regime and began ten years of elected governments that tried to oppose the greengrocer and impose social reforms, but were overthrown in 1954 when the UFCO interests were affected by these reforms. The counterrevolution of 1954. He maintained some of the reforms of the revolutionary regimes, including the dignity of the Army, but he returned to protect the interests of the North American fruit company, arguing that the revolutionary regimes were communist. In 1960, within the framework of the Cold War, the civil war began and a period of political instability, with coups d'état and fraudulent elections. The armed conflict left a balance of more than 250,000 victims —between deaths and disappearances— according to data from the Commission for Historical Clarification, according to which more than 90 percent of the massacres were committed by the Guatemalan Army and pro-government paramilitary groups.. After the transition to a democratic system in 1985, and after extensive negotiations with the guerrillas, the Peace Accords were signed in 1996, a new era began in Guatemala.

Paleoindian and Archaic Period

The Paleoindian, also called Paleoamerican, began with the arrival of man in the New World, which is currently placed by most researchers at at least 14,000 BC. C. In the Central American region, there were more emerged lands compared to today, since the sea level was much lower, during the ice age; the temperatures were below 4 to 7 °C, and the annual rainfall, from 30 to 50 percent; there was snow and even glaciers in the volcanic mountains; and the concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere were weaker, limiting the development of vegetation. The Central American ecosystems were home to a varied American megafauna, now extinct.

The earliest sure evidence of human activity is the Clovis and Folson industries, around 10,000 to 9,000 BCE. C., which indicate nomadic populations that subsisted on the hunting of megafauna. In Mesoamerica the information of this period is very scarce; In the Guatemala region, there is relatively abundant evidence of human occupation towards the final period of Paleoindia, between 10,000 and 6,500 BC. C. Multiple hunting tools of various styles have been found in several paleoindian sites such as La Piedra del Coyote, Los Tapiales and Chajbal, in the valleys of Guatemala, Chichicastenango and Quiché. Among these sites it has been found that there was already specialization in the production of hunting tools. The most common style of tools found is that of grooved tips, native to the Central American region; the second most common style is the fluted Clovis type, which has a high affinity with the Clovis points of eastern North America.

During the Archaic period, the domestication of different agricultural species occurred in several regions of Mesoamerica and America in general, which would later exchange knowledge. Corn was domesticated around 6,000 B.C. C. in the Tehuacán valley. In Cerro de las Conchas, Chiapas, there was an important human occupation around 5,500 BC. C. In Sipacate, Escuintla, possible evidence of teosinte or corn pollen contemporary to that of the occupation of Cerro de las Conchas has been found. Around 3,500 B.C. C. human activities intensify on the South Coast of Guatemala.

Pre-Hispanic period

Different groups of people populated Guatemala during pre-Hispanic, also known as pre-Columbian, times, the most important being the Mayan civilization, which flourished in most of what is now Guatemala and its surrounding regions for approximately two thousand years before the arrival of the Spanish. Its history is divided into three periods: Preclassic, Classic and Postclassic.

Most of the large Maya cities in the Petén region and the northern lowlands of Guatemala were abandoned around 1000 B.C. The late Postclassic states of the central highlands—such as the kingdom of the Quiché at Q'umarkaj (Utatlán)—were still thriving upon the arrival of the Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado between 1523 and 1527.

Native settlers of the Guatemalan highlands, such as the Kakchiquel, Mam, Quiché, and Tzutujil, and the Kek'chi in the northern Guatemalan lowlands form a significant part of the Guatemalan population. In the southeast The country was dominated by the Xincas who are not linguistically related to any other Mesoamerican people.

Maya Civilization

The Mayan civilization excelled in various scientific disciplines and arts such as architecture, writing, advanced time calculation through mathematics and astronomy; The Mayan calendar is very precise and, unlike the Gregorian calendar —which is based on corrections based on leap years—, it does not have a correction mechanism and resorts to linking two originally independent cycles, known as the "haab" through an astronomical fact. » and the «long count». They were hunters, farmers, practiced fishing, domesticated animals such as turkeys and ducks; they used canoes to navigate the rivers and to travel to nearby islands. They also excelled in painting, sculpture, goldsmithing and copper metallurgy, weaving cotton and agave fiber and developing the most complete writing in pre-Hispanic America. Among the sports they practiced, the ball game stands out, which was more of a ceremony than a game.

| Period | Division | Years | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arcaico | 8000–2000 a. C. | ||

| Preclass | Early preclass | 2000–1000 a. C. | |

| Medium preclassic | Preclassic early | 1000–600 a. C. | |

| Preclassic half late | 600-350 a. C. | ||

| Preclassic late | Initial late preclassic | 350 a. C. –1 d. C. | |

| Lateral preclassic | 1 d. C. – 159 d. C. | ||

| Preclassic Terminal | 159–250 d.C. | ||

| Classic | Early Classic | 250-550 d.C. | |

| Classical Late | 550–830 d.C. | ||

| Classic Terminal | 830–950 d.C. | ||

| Postclassic | Early postclass | 950-1200 d.C. | |

| Late postclassic | 1200–1539 AD. | ||

| Colonial | 1511–1697 AD. | ||

Their development in engineering was monumental, they built great metropolises from the Preclassic Period such as the sites of San Bartolo, Cival, Nakbé, El Mirador, in the Mirador Basin, Uaxactún, Tikal, Ceibal, Río Azul, Yaxhá, Dos Pilas, Cancuén, Machaquilá, Aguateca, in the northern lowlands, located in the department of Petén and Kaminal Juyú, in the highlands of the central highlands, as well as Takalik Abaj in the department of Retalhuleu, located in the coastal zone of the ocean Pacific.

Postclassic Period

Lowlands

At the beginning of the Late Postclassic, Chichén Itzá, Mayapán and Izamal were the main Mayan cities in the Yucatán peninsula; After a war between the inhabitants of Chichen Itzá and those of Izamal, the former were expelled from the peninsula and had to settle in the Petén region, in Guatemala —specifically on the modern Isla de Flores—.

With the departure of the Itzáes, the Cocom family of Mayapán became the most powerful lineage in the region and demanded that all the leaders of the allied provinces live in Mayapán; In this way, the Mayapán League was created with sixteen provinces or city states. But in 1441, there were uprisings against the Cocoms and their leaders were sacrificed, ending the League. Thereafter, the sixteen provinces engaged in a series of civil wars that lasted until the arrival of the Spanish in the early 16th century.

It is not fully elucidated where the Itzá originated from. The proposals range from Toltecs, Mexicanized Mayas, Mayanized Toltecs, Putunes or Chontales who could have come from the Tabasco coast, from Chakanputun, Campeche, from Petén, from somewhere in the Usumacinta basin or even from the island of Cozumel. However, Erik Boot carried out an in-depth epigraphic study and discovered that the first reference to this group –so far– is found in a vessel from the Early Classic (250-600 AD) which was dedicated to a son of a itza' ajaw; and the mention on Stela 2 of Motul de San José of Ju’n Tzahk T’ok’ k’uhul itza’ ajaw who visited and supervised an unknown activity at said site; While the title of Kaaneek' –associated with the Itzá from the Late Postclassic of Lake Petén Itzá– can be located on some stelae from Xultún, Pusilhá and Ucanal, which may indicate that the Itzá originated possibly from the Central Lowlands and migrated north sometime in the VI century, this is probably why in the indigenous chronicles of Yucatán refer to them as "those who speak our language badly", since their mother tongue was Cholano and not Yucatecan. According to the Chilam Balam of Chumayel, the Itzá migrated to the Bakhalal region (present-day Bacalar), coming from Chacnovitan where they founded some cities. Centuries later they arrive at Chichén Itzá, where they had founded the lineages of Uc and Abnal.

There is a great discrepancy about the historical genesis of the city of Chichén, since it is assumed that the Itzá were the founders upon their arrival in the region, as Sylvanus G. Morley had indicated in 1946. On the other hand, Eric Thompson –based on the chronicles of Chilam Balam's books– suggested that it was conquered and taken by the Itza around 918 AD. C. Then the Itzáes would maintain a hegemony over the Yucatan Peninsula towards the Early Postclassic. It can be indicated that there is no firm evidence that can confirm that Chichén Itzá conquered the great centers of the eastern part of the peninsula -Ek Balam and Cobá-, there is no deliberate destruction of monuments or buildings, nor an abrupt change in material culture and both settlements continued to be populated at dates when Chichén Itzá had already lost its pre-eminence.

According to Fray Diego de Landa, there is a legend that the foundation of Mayapán and Chichén Itzá were closely related. indicates that Mayapán was founded by the Itzá following Chichén Itzá itself as a model, located 90 kilometers to the east. According to the Chilam Balam of Chumayel and Landa's main informant, Gaspar Antonio Chi Xiú, the settlement was established during the k’atuun 13 Ajaw (1007 - 1027 AD). However, archaeological investigations carried out by the Carnegie Institution of Washington during the 1950s revealed a small occupation around the Late Preclassic (400 BC - 100 AD), and recent radiocarbon dating yielded a possible date for the Middle Preclassic (ca. 820 - 540 BC). But it was not until the Terminal Classic when the masonry buildings began to be built in a modest way in the vicinity of the Itzmal Ch'en and X-Coton cenotes, whose style is associated with the Puuc. In the middle of the 12th century monumental architecture began to be built, and by the XIII the physiognomy of the city was as it is seen today. The great importance of this settlement is due to its peculiar political organization known as muultepal. According to the study of several colonial documents, it has been determined that the Mayapán regime was under the command of the most powerful lineages of the peninsula. Presumably the muultepal was established from the XII century and was headed by Itzá lineages – of which only the Cocom is known–, and later others of different affiliation were integrated, until its disintegration in the middle of the XVth century of our era.

The heyday of the city was during the XII century to the XV century of our era, which more or less coincides with the decline of Chichén Itzá. Several researchers link the fall of the Itza capital to Hunnac Ceel. According to Chuyamel's Chilam Balam, sometime before the beginning of katun 8 Ahau, Hunac Ceel Cauich was thrown in a ceremony into the Itza pit at Chichén Itzá, which was considered the entrance to the underworld. But he returned alive and proclaimed himself a messenger of the gods, wanting to be named Ahau of Mayapán. With the backing of the cocomes, Hunac Ceel Cauich became Halach Uinik of Mayapán. Eventually, Hunac Ceel and Chac Xib Chac, chief of the Itzáes, came into conflict; the cause of this confrontation is described in the Chilam Balam as a "betrayal" by Hunac Ceel towards the Itzá leader. In 1194, Hunac Ceel attacked Chichén Itzá with an army composed of cocomes and Chontal mercenaries, which was commanded by seven chiefs; Ah Sinteut Chan, Tzontecum, Taxcal, Pantemit, Xuchueuet, Itzcuat and Calcatecat.

According to Roys, Hunnac Ceel's betrayal consisted of the fact that he gave Chac Xib Chac a flower to smell –sak nikte'o flor de mayo– which, due to its aphrodisiac effects, caused him to fall in love with the fiancée of Ulil lord of Izamal. She was kidnapped during the wedding banquet which brought the ruler of Chichén Itzá to shame. And during this moment of weakness, the Hunnac Ceel attacked the city, forcing the Itzá to abandon it. Another version is that Izamal declared war on Chichén Itzá, and Chac Xib Chac, seeing that Ulil's armed forces were greater than his own, decided to escape together with his people to a distant place. After Hunnac Ceel took Chichén Itzá, the Chilam Balam of Chumayel agrees that the Itzá went to Chakanputun and then went into the jungle to an unknown place called Tan Xuluk Mul, where they founded the city of Saklactun Mayapán, that is, Taj Itza' – known as Tayasal or Noj Peten, on Lake Petén Itzá, Guatemala– in a k'atuun 8 Ajaw.

Ironically, Mayapán also had a violent end just like its predecessor, again in the Chilam Balam it is reported that the Itzá together with Ah Ulmil Ahau besieged Mayapán as revenge: “4 Ahau two score years; and then the land of Ich Paa Mayapán was taken by the Itza men who left their homes, together with the ajaw Ulmil and by the people of Izamal because of the betrayal of Hunnac Ceel". The end of the city occurred in the k'atuun 8 Ajaw (1441 - 1461 AD) according to the Chilam Balam of Chumayel, as always the data is somewhat confusing but makes it clear that an attack was the main cause: "from there it was taken the land of Ich Paa Mayapán, by those behind the wall, by reason of the multepal within Mayapán, by the Itza men and the ahau Ulmil". Although it is not known with certainty who conquered Mayapán, there is firm evidence of the war since the Carnegie Institution of Washington explored it in the middle of the last century. Buildings razed and burned, caches looted, as well as skeletons of individuals who suffered a violent death were reported.

Highlands and South Coast

K'iche' (K'iche' Winak)

In the early Late Postclassic, the K'iche' He stood out among the highlands, through an aggressive expansionist policy, he subdued the neighboring populations first and then almost the entire highlands. The noble houses of the K'iche' they legitimized their supremacy in the origin in the origin of their Tollan ancestors. However, Robert Carmack traces its origin to the later incursion of Toltequized Chontal-Nahua speakers from the Gulf coasts between Veracruz and Tabasco. According to the Popol Vuh, the three K'iche' Confederates, the Nimak'iche', the Ilokab', and the Tamub' were led by the four founding fathers of the K'iche' (B'alam Kitze', Balam Aq'ab, Majukutaj and Ik'i B'alam) to the Chujuyub' (circa 1200, according to Carmack), in the central highlands, where they settled and first fought for political supremacy. The most important of these was the battle of Jakawitz, the mountain considered the first K'iche' settlement, where the confederation subdued the preceding population known as 'the deer men'. According to documentary sources, Jakawitz was the starting point of sovereign Tz'ikin's military campaigns against Rabinal (to the east) and Iqomaq'i (in the Cubulco area). The K'iche' They gradually developed their military power, whose objective was to subdue other groups and turn them into vassals who had to pay tribute to them. Prisoners and members of subjugated groups were sacrificed to Tojil, the god of lightning and thunder.

For nearly 300 years they managed to keep expanding their territories. Around 1350, they consolidated their power between the Choxoy and Motagua rivers. Four generations after the battle of Jakawitz, they moved their capital from the mountains of Chujuyub' to Ismachi (or Pismachí), 15 km to the southwest. The Confederation continued to expand its rule under the leadership of the nimak'iche'.

The supremacy of these became a point of contention between the confederate groups and in the time of King Q'uq'kumatz, the dissolution of the community took place. The nimak'iche' they settled in Q'umarkaj and ended up becoming the K'iche' more powerful. Located on a plateau with difficult access, which was only reached by well-controlled roads, Q'umarkaj was an impregnable fortress, in which the members of the great houses of the K'iche' they were safe from enemy attacks. At the beginning of the 15th century, the eighth ruler of the K'iche', Q'uq&# 39; Kumatz began a policy of radical expansion and subjugated neighboring towns. With the conquests of his successor, K & # 39; iq & # 39; ab & # 39;, supported militarily by his Kaqchikel allies, the power zone of the k & # 39; iche & # 39; it reached its maximum extent in the middle of the 15th century.

The K'iq'ab'ab' and the dispatch of representatives of the dynasty to the conquered regions demanded the reorganization of Q'umarkaj society. As the largest military force in the system, the Kaqchikeles were exonerated in their status as vassals, they integrated into the system of power as a social group and with Chiawae Tz'upitaq'aj they obtained their own capital. The Kaqchikeles rose up against K'iq'ab' around the year 1470 and that they tried to kill him. As a result of that revolt, the Kaqchikeles abandoned Q'umarkaj and Chiawar Tz'upitaq'aj and founded a new capital, Iximché, also surrounded by ravines. The K'iche' They made several attempts to defeat the Kaqchikeles, but they failed. In a major battle, the K'iche' in his attempt to attack Iximché he was annihilated, resulting in the slaughter of thousands of K'iche' warriors, the capture and sacrifice of their leaders and the Tohil idol. Among the K'iche' and the tz'utujil also broke out the enmity that was increasing in a series of wars that resulted in the death of the regent k'iche' Tekum, son of K'iq'ab, late 15th century.

Spanish conquest

Advancement and governance of Guatemala

In 1523 the Spanish conquistadors arrived from the west from Mexico under the command of Captain Pedro de Alvarado, with the intention of exploring and colonizing the territories of present-day Guatemala. They first faced the K'iches and then briefly allied with the Kaqchikeles, founding their first settlement on July 25, 1524 in the vicinity of Iximché, capital of the Kaqchikeles, a town that received the name "Santiago de los Caballeros". Guatemala" in honor of the Apostle Santiago el Mayor. It is important to note that a soldier sick with smallpox arrived in Mexico and started the devastating plagues that devastated the native populations of the American continent.

On November 22, 1527, that city was transferred to the Almolonga Valley —the modern neighborhood of San Miguel Escobar in Ciudad Vieja, Sacatepéquez— due to the constant siege it suffered due to attacks by the natives. In that year, Pedro de Alvarado traveled to Spain to meet with Emperor Carlos V, who finally gave him the titles of Governor, Captain General and Adelantado of Guatemala, on December 18, 1527.

This second city was destroyed in the early morning of September 11, 1541 by an avalanche of mud and stones that descended from the top of the Agua volcano, or Hunahpú volcano as the natives called it, burying the then capital of the region and burying the city with most of its inhabitants. Among them was Governor Beatriz de la Cueva, widow of Pedro de Alvarado. All of this forced the city to be moved again to the nearby Panchoy valley, some six kilometers downstream, where the modern city of Antigua Guatemala is located. On March 10, 1543, the city council held its first session there and the city retained the same coat of arms granted in the town of Medina del Campo by royal decree on July 28, 1532, and on March 10, 1566, King Felipe II awarded it with the title of "Very Noble and Very Loyal City".

Conquest of the Cuchumatanes

In the ten years after the fall of Zaculeu, the Spanish tried to invade the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes to conquer the Chuj and Q'anjob'al peoples and to search for gold, silver and other riches; however, the remoteness and difficult terrain made their conquest difficult.

After the Spanish conquered the western part of the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes, the Ixils and Uspantecos (uspantek) managed to evade them; These towns were allies and in 1529 Uspantec warriors were harassing Spanish forces trying to foment rebellion among the Quiché. Gaspar Arias, a Guatemalan magistrate, entered the eastern Cuchumatanes with an infantry of sixty Spanish soldiers and three hundred indigenous allied warriors and by early September had succeeded in temporarily imposing Spanish authority in the area occupied by the modern towns of Chajul and Nebaj. Then, as he was marching east to Uspantán, Arias received word that the acting governor of Guatemala, Francisco de Orduña, had removed him as magistrate and he had to return to Guatemala, leaving the inexperienced Pedro de Olmos in command. Olmos launched a disastrous frontal assault on the city, where the Spanish were ambushed from the rear by more than two thousand Uspantec warriors; the survivors who managed to escape returned, harassed, to the Spanish garrison at Q'umarkaj.

A year later, Francisco de Castellanos led a new military expedition against the Ixils and Uspantecs, with eight corporals, thirty-two mounted men, forty Spanish soldiers on foot, and hundreds of indigenous allied warriors; On the highest slopes of the Cuchumatanes, in the area occupied by the modern municipality of Sacapulas, they faced almost five thousand Ixil warriors from Nebaj and nearby settlements. Spanish forces besieged the city and their indigenous allies managed to scale the walls, penetrate the fortress and set it on fire; the survivors were branded as slaves to punish them for their resistance. The inhabitants of Chajul, learning of this, immediately surrendered and The Spanish continued towards Uspantán where there were ten thousand warriors, coming from the area occupied by the modern municipalities of Cotzal, Cunén, Sacapulas and Verapaz; the deployment of the Spanish cavalry and the use of firearms decided the battle in favor of the Spanish who occupied Uspantán and again branded all surviving warriors as slaves. The surrounding towns also surrendered and in December 1530 the conquest of the Cuchumatanes ended.

Requirement for Palacios Rubios, parcels and repartimientos

There were three mechanisms of colonization that the Spanish conquerors used to appropriate the lands and labor of the natives: the requirement of Palacios Rubios, the encomiendas, and the repartimientos.

The requirement of Palacios Rubios was a legal prerequisite for any armed action of conquest; by this mechanism, the indigenous people were required —by reading a manifesto or ultimatum prepared by the jurist Juan López de Palacios Rubios— to convert to Christianity and practice obedience to the royal authority. However, the mechanism was quickly perverted, coming to be read symbolically several kilometers from the next village to be taken. Not to mention that the reading was done in Spanish, which the indigenous people did not know, who, in any case, were not willing to convert for the mere fact of reading a letter. On other occasions, a few indigenous people were read, who were asked to explain it to their compatriots and were given enough days to accept the proposal; after the days, if there was no response, the conquerors attacked the towns. In other circumstances, the requirement was read from the ships before docking or from the top of hills far from the towns and a notary certified that it had been read to the natives.

The encomienda and the repartimiento were systems instituted by Christopher Columbus in the recently discovered Antilles. The repartimiento consisted of distributing land and groups of indigenous people as labor to work them while the encomienda consisted of delivering groups of indigenous people to Christianize them, who were put to work as slaves until their annihilation.

Cortés in the Petén

In 1525, after the conquest of the Aztec empire, Hernán Cortés led an overland expedition to Honduras and traversed the Itzá kingdom in what is now the Petén department of Guatemala. His goal was to put down the rebellion of Cristóbal de Olid, whom he had sent to the conquest of Honduras and who had established himself independently upon reaching that territory. Cortés's expedition had one hundred and forty Spanish soldiers, ninety-three of them mounted, three thousand Mexican warriors, one hundred fifty horses, a herd of pigs, artillery, ammunition and other supplies. He was also accompanied by six hundred Chontal Mayan bearers from Acalán. On March 13, 1525, the expedition members reached the north shore of Lake Petén Itzá.

After learning that Olid's rebellion had been put down, Cortés returned to Mexico by sea; there were no other formal contacts between the Spanish and the Itzá until the arrival of Franciscan priests in 1618, when apparently the cross left by Cortés was still standing in Nojpetén. Several unsuccessful military attempts to conquer the Lacandones— who remained free until 1697—although the Dominicans undertook a peaceful conversion in the "War Lands" of Tezulutlán.

Dominicans in Verapaz

In November 1536, friar Bartolomé de las Casas, O.P. settled in Santiago de Guatemala. Months later Bishop Juan Garcés, who was a friend of his, invited him to move to Tlascala. Later, he moved back to Guatemala. On May 2, 1537, he obtained from the licensed governor Don Alfonso de Maldonado a written commitment ratified on July 6, 1539 by the Viceroy of Mexico Don Antonio de Mendoza, that the natives of Tuzulutlán, when they were conquered, would not be entrusted but that they would be vassals of the Crown. Las Casas, along with other Dominican friars, sought out four indigenous Christians and taught them religious songs where basic issues of the Gospel were explained. Later he led a procession that brought small gifts to the natives and impressed the cacique, who decided to convert to Christianity and be a preacher to his vassals, and was baptized with the name of Juan. The natives consented to the construction of a church but another cacique named Cobán burned the church. Juan and his men, accompanied by Las Casas and Pedro de Angulo, went to talk to the indigenous people of Cobán and convinced them of their good intentions.

Las Casas, Fray Luis de Cáncer, Fray Rodrigo de Ladrada and Fray Pedro de Angulo, O.P. They took part in the reduction and pacification project, but it was Luis de Cáncer who was received by the chief of Sacapulas, managing to carry out the first baptisms of the inhabitants. The cacique "Don Juan" took the initiative to marry one of his daughters to a principal of the town of Cobán under the Catholic religion.

Las Casas and Angulo founded the town of Rabinal, and Cobán was the head of Catholic doctrine. After two years of effort, the reduction system began to have relative success, as the indigenous people moved to more accessible lands and towns were founded in the Spanish way. The name of "Land of War" was replaced by that of "Vera Paz" (true peace), a name that became official in 1547.

Foundation and transfers of the capital city

The capital city of Guatemala was founded by Pedro de Alvarado in 1524 on the feast day of Santiago, for which reason it was known as Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala. Saint Cecilia was also considered the patron saint of the city, Because in 1526 the Kakchikel kings revolted until they were finally subdued on the day this saint of the Catholic Church is celebrated.

On September 9, 1541, Pedro de Alvarado died and the city council appointed his widow, Mrs. Beatriz de la Cueva, as governor in his place; but he could only hold the position for two days, because on September 11 the flooding of the city occurred: heavy rains loosened the earth on the highest slopes of the Agua Volcano and from there a landslide occurred that destroyed everything in its path. At first it was decided to move the city to the Tiangues valley in Chimaltenango, but finally, the engineer Juan Bautista Antonelli indicated that the Panchoy valley was better. Bishop Francisco Marroquín and Francisco de la Cueva, Beatriz's brother, were elected as new governors. They governed until May 17, 1542, when Alonso de Maldonado, envoy of the viceroy of Mexico, arrived.

As a consequence of the Capitulations of Tezulutlán, King Carlos I promulgated on November 20, 1542 the New Laws that prohibited the slavery of the indigenous people and ordered that all be freed from the encomenderos and placed under the direct protection of the Crown.

In 1543 the city was moved to the Panchoy valley; the new city had a rectilinear layout and land was given around the central square for the town hall and the cathedral; the rest went to residents and religious orders. The engineer Antonelli was in charge of the layout.

The first Audiencia that was established in the Kingdom of Guatemala was the «Audiencia de los Confines», named for being between the confines of New Spain and Peru. It was founded in the New Laws of 1542, it was established in Gracias a Dios in Honduras and its first president was Mr. Alonso de Maldonado; the territory of the Audiencia was Yucatan, Chiapas, Soconusco, Central America and Panama. On June 16, 1548, the Audiencia moved to the city of Antigua Guatemala, with Alonso López de Cerrato arriving as president. There were many problems between the Audiencia of the representatives of the Crown and the council of the conquerors of Guatemala, to the point that the Audiencia was suppressed in 1565.

In 1551, the city's cathedral was invested with all the privileges and indulgences of the Church of Santiago in Galicia by Pope Julius III.

With the new "Audiencia de Guatemala" established in 1570, the colonial era proper began, and the highest authorities of the Kingdom of Guatemala were the Catholic archbishop and the president of the Royal Audience. For its part, the city de Santiago de los Caballeros reached such splendor that it was considered one of the most beautiful in the New World.

Timeline of the conquest

| Summary Chronology of the Conquest of Guatemala | ||

|---|---|---|

| Date | Success | Modern Department (or Mexican state) |

| 1521 | Tenochtitlan conquest. | Mexico |

| 1522 | Allies of the Spaniards explore the region of Soconusco and receive delegations from the k'iche' and the kakchiqueles. | Chiapas, Mexico |

| 1523 | Pedro de Alvarado arrives in Soconusco. | Chiapas, Mexico |

| February-March 1524 | The Spaniards defeat the k'iche'. | El Quiché, Quetzaltenango, Retalhuleu Such,itepéquez y Totonicapán |

| 8 February 1524 | Battle of Zapotitlán, Spanish victory over the k'iche'. | Suchitepéquez |

| 12 February 1524 | First battle of Quetzaltenango that ends with the death of Tecún Uman, legendary commander k'iche. | Quetzaltenango |

| 18 February 1524 | Second battle of Quetzaltenango. | Quetzaltenango |

| March 1524 | The Spaniards in charge of Pedro de Alvarado root Q'umarkaj, the capital of the k'iche'. | The Quiché |

| 14 April 1524 | The Spaniards enter Iximché and join the kakchiqueles. | Chimaltenango |

| 18 April 1524 | The Spaniards defeat the Tzu'tujiles in a battle on the shores of Lake Atitlán. | I just... |

| 9 May 1524 | Alvarado defeats Panacal or Panacaltepeque pipils near Izcuintepeque. | Escuintla |

| 26 May 1524 | Alvarado defeats the Xincas of Atiquipaque. | Santa Rosa |

| 27 July 1524 | Iximché is declared the first colonial capital of Guatemala. | Chimaltenango |

| 28 August 1524 | The kakchiqueles leave Iximché and break the alliance with the Spanish. | Chimaltenango |

| 7 September 1524 | The Spaniards declare war on the kakchiqueles. | Chimaltenango |

| 1525 | The poqomam capital falls into the hands of Pedro de Alvarado. | Guatemala |

| 13 March 1525 | Hernán Cortés arrives at Lake Petén Itzá. | Petén |

| October 1525 | Zaculeu, the capital of the Mam people, surrenders to Gonzalo de Alvarado and Contreras after a prolonged siege. (see: Expedition to the territory of the Mames) | Huehuetenango |

| 1526 | The Chajoma people rebel against the Spaniards. | Guatemala |

| 1526 | Spanish captains sent by Alvarado managed to conquer Chiquimula. | Chiquimula |

| 9 February 1526 | Spanish deserters burn Iximché. | Chimaltenango |

| 1527 | The Spanish leave their capital in Tecpán Guatemala. | Chimaltenango |

| 1529 | St. Matthew Ixtatan is entrusted to Gonzalo de Ovalle. | Huehuetengo |

| September 1529 | The Spaniards are defeated in Uspantan. | The Quiché |

| April 1530 | Rebellion in repressed Chiquimula. | Chiquimula |

| 9 May 1530 | The kakchiqueles surrender to the Spanish. | Sacatepéquez |

| December 1530 | Ixiles and uspantecos surrender to the Spanish. | The Quiché |

| 2 May 1537 | The Chapters of Tezulutlán, the agreements signed by Fray Bartolomé de las Casas and Alonso de Maldonado to peacefully conquer the territories of Tezulutlán (formed by what would later be Alta Verapaz) and the Lacandona Jungle (Chiapas) | Alta Verapaz y Chiapas |

| 1543 | Coban Foundation. | Alta Verapaz |

| 1549 | First reductions of the Chuj and q'anjob'al villages. | Huehuetenango |

| 1555 | The Mayas of the lowlands kill Francisco de Vico. | Alta Verapaz |

| 1560 | Reduction of Topiltepeque and of the Lacandon ch'oles. | Alta Verapaz |

| 1618 | Franciscan Missionaries arrive at Nojpetén, the capital of the itza'. | Petén |

| 1619 | Other missionary expeditions to Nojpetén. | Petén |

| 1684 | Reduction of San Mateo Ixtatán and Santa Eulalia. | Huehuetenango |

| 29 January 1686 | Melchor Rodríguez Mazariegos departs from Huehuetenango, leading an expedition against the lacandons. | Huehuetenango |

| 1695 | The Franciscan friar Andrés de Avendaño tries to convert the itza'. | Petén |

| 28 February 1695 | Spanish Expeditions against the Lacandon people simultaneously depart from Coban, San Mateo Ixtatán and Ocosingo. | Alta Verapaz, Huehuetenango and Chiapas |

| 1696 | Fray Andrés de Avendaño is forced to flee from Nojpetén. | Petén |

| 13 March 1697 | Nojpetén surrenders to the Spaniards after a fierce battle. | Petén |

Colonial period

During this colonial period, which lasted almost three hundred years, Guatemala was a captaincy general that in turn depended on the Viceroyalty of New Spain, modern Mexico. It stretched from the Soconusco region—now in the state of Chiapas, Mexico—to Costa Rica. Although this region was not as rich in minerals and metals as Mexico and Peru, it stood out mainly in agricultural production, especially sugar cane, cocoa, precious woods, and indigo ink for dyeing textiles.

17th century

Doctrines of native Guatemalans

The Spanish crown focused on the catechization of the indigenous people; the congregations founded by the royal missionaries in the New World were called "indian doctrines" or simply "doctrines". Originally, the friars had only a temporary mission: to teach the Catholic faith to the indigenous people, to later make way for secular parishes. such as those established in Spain; to this end, the friars should have taught the gospels and the Spanish language to the natives. Once the indigenous people were catechized and spoke Spanish, they could begin to live in parishes and contribute to the tithe, as the peninsulares did.

But this plan was never carried out, mainly because the crown lost control of the regular orders as soon as the members embarked for America. On the other hand, protected by their apostolic privileges to help the conversion of the indigenous, the missionaries only attended to the authority of their priors and provincials, and not to that of the Spanish authorities or to those of the bishops. The provincials of the orders, in turn, only rendered accounts to the leaders of their order and not to the crown; once they had established a doctrine, they protected their interests in it, even against the interests of the king and in this way the doctrines became Indian towns that remained established for the rest of the colony.

The doctrines were founded at the discretion of the friars, since they had complete freedom to establish communities to catechize the indigenous people, in the hope that these would pass over time to the jurisdiction of a secular parish that would be paid the tithe; in reality, what happened was that the doctrines grew without control and never passed to the control of parishes. The collective administration by the group of friars was the most important characteristic of the doctrines, since it guaranteed the continuation of the community system in case one of the leaders dies.

Events that occurred in the city of Santiago de los Caballeros in Guatemala

Pedro de San José Betancur, or Santo Hermano Pedro, arrived in Guatemala in 1650 from his native Tenerife; upon disembarking he suffered a serious illness, during which he had the first opportunity to be with the poorest and most disinherited. After his recovery he wanted to carry out ecclesiastical studies but, unable to do so, he professed as a Franciscan tertiary in the Convent of San Francisco. He founded shelters for the poor, natives and homeless people and also founded the Order of the Brothers of Our Lady of Bethlehem in 1656, in order to serve the poor. Santo Hermano Pedro wrote several works, among them: Instruction to brother De la Cruz, Crown of the Passion of Jesus Christ our good or Rules of the Betlemite Confraternity. On the other hand, he was the first American literacy and the Order of the Betlemites, in turn was the first religious order born in the American continent. Pedro de San José Betancur was a man ahead of his time, both in his methods for teaching the illiterate to read and write and in his treatment of the sick.

In 1660, the printer José de Pineda Ibarra arrived in Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala, hired by the Guatemalan ecclesiastics. He worked in printing, binding, and buying and selling books; He died in 1680, inheriting the printing press from his son Antonio, who continued to operate it until his death in 1721.

On January 31, 1676, by Royal Decree of Carlos II, the Royal and Pontifical University of San Carlos Borromeo was founded, the third university founded in America, where many important figures of the country studied, among them Fray Francisco Ximénez, discoverer of the Popol Vuh manuscript —and who also partially translated it into Spanish— and Dr. José Felipe Flores, an eminent Guatemalan protomedician and personal physician to the King of Spain.

During the 1690s, due to Guatemala's location on the American Pacific coast, it became a commercial node in the trade between Asia and Latin America when it emerged to become a supplanting trade route for the Manila Galleons.

In the art of the 17th century, the master painter Pedro de Liendo and the master sculptor Quirio Cataño stand out.

Conquest of Petén

The Itza had resisted all attempts at Spanish conquest since 1524. In 1622 a military expedition led by Captain Francisco de Mirones, accompanied by Franciscan friar Diego Delgado, left Yucatán; this expedition became a disaster for the Spanish who were massacred by the Itzaes. In 1628 the Manché Chols in the south were placed under the administration of the colonial governor of Verapaz as part of the Captaincy General of Guatemala. In 1633, the Manche Chol rebelled unsuccessfully against Spanish rule. In 1695 a military expedition that left Guatemala tried to reach Lake Petén Itzá; this was followed by missionaries who left Mérida in 1696, and in 1697 by the expedition of Martín de Ursúa y Arizmendi, which left Yucatán and which resulted in the final defeat of the independent kingdoms of central Petén, and their incorporation into the Spanish Empire.

Castle of San Felipe de Lara

The Castillo de San Felipe de Lara is a fortress located at the mouth of the Río Dulce with Lake Izabal in eastern Guatemala. It was built in 1697 by Diego Gómez de Ocampo to protect Spanish colonial properties against attacks by English pirates. The Río Dulce connects Lake Izabal to the Caribbean Sea and was exposed to repeated pirate attacks between the 16th century and the xviii. King Philip II of Spain ordered the construction of the fortress to counter looting by pirates. In 2002 it was inscribed on the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

18th century

The San Miguel Earthquakes

The strongest earthquakes that the city of Santiago de los Caballeros experienced before its final transfer in 1776 were the San Miguel earthquakes in 1717. At that time, the domination of the Catholic Church over the vassals of the Spanish Crown was absolute and this meant that any natural disaster was considered a divine punishment. In the city, the inhabitants also believed that the proximity of the Fuego Volcano was the cause of the earthquakes; the chief architect Diego de Porres went so far as to affirm that the earthquakes were caused by the eruptions of the volcano.

On August 27, there was a very strong eruption of Volcán de Fuego, which lasted until August 30; The residents of the city asked for help from the Holy Christ of the cathedral and from the Virgen del Socorro, who were the sworn patrons against the volcano's fire. On August 29, the Virgen del Rosario came out in procession after a century without going out and there were many more processions of saints until September 29, the day of San Miguel; the first earthquakes in the afternoon were slight, but at around 7 pm there was a strong tremor that forced the residents to leave their houses; The tremors and rumblings continued until four in the morning. The neighbors went out into the street and shouted confessing their sins, thinking the worst.

The earthquakes in San Miguel damaged the city considerably, to the point that the Royal Palace suffered damage to some rooms and walls. There was also a partial abandonment of the city, a shortage of food, a lack of labor, and much damage to the city's buildings; in addition to numerous deaths and injuries. These earthquakes made the authorities think about moving the city to a new settlement less prone to seismic activity; the residents of the city strongly oppose the transfer, and even took over the Royal Palace in protest of it. In the end, the city did not move from its location, but the number of elements in the Dragon Battalion to keep order was considerable. The damage to the palace was repaired by Diego de Porres, who finished it in 1720; although there are indications that there were more works by Porres until 1736.

The inhabitants of the city of Santiago de los Caballeros feared earthquakes, but not as much as smallpox epidemics, since they occurred approximately every fifteen years and caused more deaths than earthquakes. The earthquakes were responsible, yes, for the change in the architectural style of the city and for the loss of valuable altarpieces and paintings.

Rafael Landívar

The Church of the Great Father Augustine, new at the expense of the generosity of N. Catholico Rey D. Phelipe V (who enjoys God) has become worse, than if he were on the ground, for the PPs need. of much cost to bring them down, and of arbitious ingenuities, so that the workers do not sin; to this it is added, that the Convent is uninhabitable, and its inhabitants in rare discomfort, and added poverty. I saw through my eyes the ruin caused by the Church, and the Convent of Nrah. Mother and Mrs. de las Mercedres, and I can't stop in silence when it came to the ruin of the Church... Today the Sacred Image is placed in the Portería with the Venerable, and Holy Image of Jesus Nazarene, which is venerated there, which suffered; for though the Bobeda of his Chapel is completely destroyed, he stood. —Agustín de la Caxiga y Rada: A brief account of the regrettable estrago, which suffered this city of Santiago de guathemala, with the quatro day earthquake of March, this year of 1751. |

The poet and priest Rafael Landívar began his academic training at the age of eleven at the Colegio Mayor Universitario de San Borja, which at the same time was a Jesuit seminary. In 1744 he enrolled in the Royal and Pontifical University of San Carlos, where he was awarded a bachelor's degree in philosophy in 1746, when he was not yet fifteen years old. A little over a year later, in May 1747, he obtained the degrees of Licentiate in Philosophy and Master. In 1749 he moved to Mexico to enter the religious order of the Society of Jesus and was ordained a priest in 1755. Upon his return to Guatemala, he served as rector of the San Borja school.

On March 4, 1751, a new earthquake ruined the city of Santiago de los Caballeros, although the damage was not enough to consider moving the city. In 1767, due to the Pragmatic Sanction against the Jesuits by the King Carlos III of Spain, Landívar was banished from the American lands and together with all his companions of the order, he went first to Mexico, and then to Europe, settling in Bologna, Italy. It is there that he published his book "Rusticatio Mexicana" (Through the Fields of Mexico), in Latin, as well as his "funeral prayer" on the death of Bishop Figueredo y Victoria, benefactor of the Society of Jesus.

The Bourbon Reforms

In 1754, by virtue of a Royal Decree part of the Bourbon Reforms, all the parishes of the regular orders were transferred to the secular clergy. In 1765 the Bourbon reforms of the Spanish Crown were published, which sought to recover royal power over the colonies and increase tax collection. With these reforms, tobacconists were created to control the production of intoxicating beverages, tobacco, gunpowder, cards and the patio of roosters. The royal treasury auctioned the tobacconist annually and an individual bought it, thus becoming the owner of the monopoly of a certain product. That same year, four sub-delegations of the Royal Treasury were created in San Salvador, Ciudad Real, Comayagua and León and the political-administrative structure of the Kingdom of Guatemala changed to fifteen provinces:

In addition to this administrative redistribution, the Spanish crown established a policy tending to diminish the power of the Catholic Church, which until then was practically absolute over the Spanish vassals. The church's de-empowerment policy was based on the Enlightenment.

Problems of the Catholic Church

In America, relations between the Spanish Crown and the Catholic Church began to break down in the 18th century; but there were also problems between the secular clergy and the regular clergy, since the doctrines of the regular clergy were being secularized. In other words, the priests who did not belong to the religious orders and who came from the lower classes of society were left with the parishes that until then had belonged to the powerful religious orders, made up of members of the elite classes of colonial society..

In the 17th century there was a rise of the secular clergy, with a considerable increase in priestly ordinations that managed to satisfy the demand for parish priests in the Kingdom; The Dominicans, for example, lost almost all their parishes, except those of La Veparaz; For their part, the Franciscans and Mercedarians were stripped of most of their doctrines in the Kingdom of Guatemala. By 1768, when Archbishop Pedro Cortés y Larraz arrived in Guatemala, the powerful orders of yesteryear were only in charge of 34 of the 289 parishes in the archdiocese.

After a strong conflict in Paraguay between the Jesuits and the Spanish authorities for control of the missions, and after other difficulties in Europe, the Jesuits were expelled from Spanish territories in 1767.

The Earthquakes of Santa Marta

By 1773, the Kingdom of Guatemala was vast, with a jurisdiction spanning more than 2,400 kilometers in length, bounded by the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean to the south; It had three suffragan bishoprics, eleven cities, many towns, and approximately nine hundred towns, divided into twenty-four governments and mayoralties dominated by the Royal, Pretorial Audience, presided over by the president, the council, and the regiment. Among the dependencies of the Audiencia were: land courts, deceased property courts, crusade courts, sealed paper and community property courts, provincial ordinary, court of accounts, and those of the respective real income. For their part, the Guatemalan Creoles opposed the real power of the City Council, which was made up of two ordinary mayors, thirteen aldermen, a trustee and mayordomo. And finally, the ecclesiastical power —which was directed by the archbishop and the superiors of the regular orders—had nine prebendaries, five dignitaries, two rector priests, eight religious convents, five nuns, three devouts, and two schools.

The transfer of the capital caused Guatemala City to lose importance and political force before the provinces of the Kingdom of Guatemala, since Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción never had the beauty and grandeur of Santiago de los Caballeros and when it was declared Independence in 1821, the city was half built and failed to hold its own as the capital of the Central American Federation.

19th century

The region continued to flourish. Industries such as cocoa and sugar cane flourished throughout Guatemala's colonial period, creating great wealth and allowing the development of other industries, whose boom lasted until the end of the century xviii. The last decades of the 18th century meant for the Spanish Crown an immense waste of human and economic energy destined to support and bring to fruition repeated war projects in the that was involved The result of expansionist jealousy, as well as political-economic advances, had placed Spain in a rather difficult situation: it was not feasible to succumb to the power of neighboring powers, but facing such warlike undertakings meant innumerable human and economic sacrifices.

On the other hand, his vast overseas possessions were in themselves another great undertaking in which he had to invest such energies and resources, albeit in different ways; as well as watching over them as a valuable treasure on which their own and foreign eyes were set. An important aspect that deserved obligatory care on the part of the high Spanish royal bureaucracy, as well as the efforts and investments already indicated, was the commercial-maritime traffic that sustained the metropolis and its colonies. Through it, the pulse and rhythm of relations between the two continents could be detected.

This real concern about the maintenance and conservation of a continuous relationship in the commercial field can be explained by the factors that constituted it, such as, on the one hand, the wealth in precious metals and raw materials that America provided, as well as the consumer market that she herself meant for peninsular genres and products. This exchange, most of the times unequal for the overseas colonies, represented a considerable line in the peninsular real economy. Hence its constant vigilance and protection, manifested in a whole series of royal provisions that for almost three centuries kept a clear line of thought: the exclusive conservation of trade with the colonies as something inherent and imaginable only for the Spanish Crown, without contemplating the interference in said relationship, of other nations. The war with England in the last years of the 18th century posed difficult problems for that commercial relationship, since the English forces were well acquainted with the neuralgic points of the Spanish economy and attacked them frontally.

Conjuration of Bethlehem

In 1811 José de Bustamante y Guerra was appointed captain general of Guatemala, at a time of great independence activity; and initially he developed an enlightened reformist policy. However, before the revolution of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla and José María Morelos in Mexico, he prepared troops in Guatemala and created the "Fernando VII volunteer corps" and from his position he faced the local constitutionalists, harshly repressing the independentistas. He also opposed the liberal constitution of 1812.

Since October 28, 1813, and after the election of the rector of the Royal and Pontifical University of San Carlos Borromeo, several meetings had been held in the priory cell of the Convent of Belén, organized by Fray Juan Nepomuceno de la Concepción in order to overthrow Captain General Bustamante y Guerra and achieve the independence of the region. In November there was another meeting at the home of Cayetano and Mariano Bedoya, younger brothers of Doña Dolores Bedoya de Molina, and brothers-in-law of Pedro Molina Mazariegos Among the conspirators there were various members of both the regular and secular clergy, demonstrating the interest of the different factions of the Catholic Church in the uprising against Bustamante and Guerra.

On December 21, 1813, Bustamante y Guerra learned that seditious people were meeting in the convent of Belén to attempt an uprising due to a denunciation of José Prudencio de La Llana, and he issued an order so that Captain Antonio Villar and his assistant, Francisco Cáscara, will arrest the religious of that monastery. Several conspirators would be imprisoned in the attack. This resolution was communicated by the mayor of the town hall on the 24th; from then on, until the following month, others would be arrested. An arrest warrant was also issued against councilor José Francisco Barrundia, who managed to escape.

Upon finding himself discovered, the dragoon lieutenant Yúdice wrote to Bustamante and Guerra to ask for the king's clemency and give him names of the conspirators. Bustamante also commissioned his nephew. the Carmelite Fray Manuel de la Madre de Dios, in the post office, to open all correspondence that fell into his hands; all those captured were put on trial and sentenced to different penalties.

Bustamante y Guerra later denounced his successor named Juan Antonio de Tornos, mayor of Honduras, for alleged liberal tendencies and thus achieved his confirmation in his position by Ferdinand VII in 1814. He was dismissed in August 1817 and returned to Spain in 1819. That same year he once again became part of the Junta de Indias. In 1820 he was rewarded with the Grand Cross of the American Order of Isabella the Catholic and was appointed General Director of the Navy until 1822. In 1823 he was a member of the Board of Expeditions to America, and a year later, he returned again to the General Directorate of the Navy and worked in the Ministry of the Navy in Madrid until his death in 1825, his military position being that of lieutenant general.

Totonicapán uprising

By 1820, Atanasio Tzul was recognized as an unofficial representative of the Linkah, Pachah, Uculjuyub, Chiché and Tinamit partialities in Totonicapán; In the same year, with the representation described above and in view of the interest of his people in ending church taxes and tribute, Tzul joined forces with Lucas Aguilar and the Mayor of Totonicapán, Narciso Mallol. Together they fought against the power of the Spanish colony, led by the captain general of the Kingdom of Guatemala, the Archbishop of Guatemala Ramón Casaus y Torres, the local ladino elite and the chiefs of Totonicapán, who were differentiated from the rest of the indigenous population and they had certain privileges due to their support for the European conquest. Royal tributes had been abolished in 1811 by the Cortes of Cádiz, but were imposed again by King Ferdinand VII.

The political and military weakness of the Spanish empire, the first attempts for political autonomy and the competition between Spanish officers were key to the success of the uprising. Thus, the rejection of the tribute, the removal of the Mayor, and the José Manuel Lara de Arrese and the imposition of his own government.

For at least a few days between July and August 1820, Tzul acted as the most prominent representative of the indigenous government, though he was later flogged for nine days and imprisoned in Quetzaltenango, after the movement suffered repression at the hands of of around a thousand ladino militiamen. In March 1821, Tzul was released, after a demonstration by Totonicapense individuals and requesting a pardon. This uprising is especially remembered for the imposition of the Royal Attributes, where Atanasio Tzul put on his crown of Mr. San José and his wife, Felipa Soc, he put the crown of Santa Cecilia.

The proclamation of independence

In 1818 the implacable Bustamante left power and was replaced by Carlos Urrutia, a man of weak character and in whose government the independentistas gained ground. In 1820 the King of Spain Ferdinand VII was forced to reestablish the constitution of 1812, as a result of which freedom of the press was implemented in Central America. In that same year, Dr. Pedro Molina Mazariegos began to publish El Editor Constitucional, a newspaper that criticized the government of the colony, defended the rights of Central Americans, and promoted independence.

In Mexico, the revolution obtained a complete triumph and through the Plan of Iguala declared its total independence from Spain on February 24, 1821. This news disconcerted the Spanish authorities in Guatemala and at the same time served as a stimulus to the independence cause. On March 9, under pressure from the pro-independence liberals, Captain General Carlos de Urrutia —an infirm character with a weak character— left his post to be filled by Army Deputy Inspector Gabino Gaínza, who had recently arrived in Guatemala. Gainza He was liked by the independentistas, because in addition to being a man of a very advanced age, he was also weak and fickle. Under his command, Central America experienced intolerable levels of social unrest that forced the provincial council to ask Gainza for a meeting to discuss the difficult issue of independence.

Independence and the United Provinces of Central America

By the year 1820, the Constitution of Cádiz was put back into force, due to the events provoked by Rafael del Riego in the month of January; In addition, the deputations of Guatemala and León were reinstated on July 13 of that year. José Matías Delgado was a member of the Provincial Advisory Board together with José Simeón Cañas, Mariano Beltranena, José Valdez, José Antonio Rivera Cabeza de Vaca, and José Mariano Calderón, prior to the establishment of the constitution in the region on the 26th of that month.

However, by the year 1821 news was received in the Kingdom of Guatemala of the proclamation of the Plan of Iguala in the Viceroyalty of New Spain in the month of February, in which independence from the Spanish Empire was declared. Ciudad Real de Chiapas also declared itself independent in August. Given the facts, Gabino Gaínza, who was in charge of the General Captaincy of Guatemala, was pressured by the Central American Creoles to proclaim independence immediately.

Captain General Gaínza then, responding to this call, assembled a board of notables made up of the archbishop, deputies, military chiefs, the prelates of the religious orders, and treasury employees. In that meeting chaired by Gainza himself, those present freely expressed their opinion. Mr. José Cecilio del Valle took the floor and demonstrated the necessity and justice of Independence, stating that, in order to proclaim it, the vote of the Provinces must first be heard. However, the Creoles who had gathered in the Plaza de Armas called out for independence, and it was proclaimed that same day, September 15, 1821. Del Valle wrote that document, as well as the manifesto published by Captain General Gainza on independence. and the formation of the constitution.

It was also determined that the election of representatives be made by the same electoral boards that had elected deputies to the courts of Spain, observing the previous laws for the election procedure; that the Constituent Congress meet on March 1, 1822; that the Catholic religion be preserved "in all its integrity and purity"; and, finally, that while the country was being constituted, Chief Gabino Gaínza would continue to lead the government, acting in accordance with a Provisional Consultative Board.

Upon learning of the events in San Salvador, on October 27 the Advisory Board appointed José Matías Delgado as Mayor of the province, to calm down the spirits and assume "political command and act in the military as required by the circumstances". On his way through Santa Ana, he released the Arce, Rodríguez and Lara who were being taken prisoner to Guatemala, and upon arriving in San Salvador, Barriere left command of the province, and the royalist volunteer troops They were disarmed and discharged. The Salvadorans decided to organize themselves as a Provincial Council according to the Constitution of Cádiz, with Delgado as mayor-president.

Annexation to the Mexican Empire

Despite the new political situation, there was indecision among the authorities of the Central American provinces, since some advocated total independence and others adopted the Iguala Plan and submission to the Mexican Empire of Agustín de Iturbide. Precisely, Gaínza learned of Iturbide's invitation on November 27 for the Kingdom of Guatemala to form, together with Mexico, "a great empire", since Guatemala, according to Alejandro Marure, "was still powerless to govern itself." ". He also announced the approach of a "protection army", whose mission was "to protect with arms... the lovers of their homeland".

In fact, the annexationist faction to the Mexican Empire, made up of the Creoles of Guatemala City and members of the regular orders of the Catholic Church, wanted to maintain hegemony in the region after independence, and began to assert itself in Guatemala, since they feared that the Central American congress stipulated by the independence act of September 15, which should "decide the point of general and absolute independence", would be contrary to their interests. By consulting the open councils, on January 5 the annexation was decreed by the Consultative Board, which was later dissolved. However, only the councils of San Salvador and San Vicente fully expressed their opposition, and they would later become a bulwark of the Central American Liberal Party.

Days before, and in view of the unstable situation in the provinces, the government headed by Delgado had sent an invitation to the Provinces of León and Comayagua on December 25, 1821 to join San Salvador and thus form a kind of "tripartite entity". In the same way, the city council of San Salvador had expressed its position of resolving its fate through a Central American national congress, as the only one empowered to resolve the matter.

The offensive from Guatemala to subdue San Salvador began with the deployment of troops under the command of Sergeant Major José Nicolás de Abós y Padilla, who engaged in battle with the Salvadoran armies commanded by Manuel José Arce, who triumphed in the battle of Plain the Thorn. Another offensive under the command of Manuel Arzú, despite reaching San Salvador, was unable to consolidate the occupation. To cease hostilities, an agreement was signed on October 10, 1822 between Salvadoran representatives and the Mexican Empire, a pact in which the will of the provinces that had submitted to Mexico and also those that wished to submit to San Salvador was recognized. In the end, the agreement was left to the discretion of Iturbide, who took the conduct of San Salvador as dissent and ordered its submission.

Vicente Filísola commanded the Mexican imperial troops over San Salvador, but on November 12 the Salvadoran government agreed to incorporate it into the Mexican Empire. as well as the erection of the episcopal chair was recognized. In addition, they would maintain the weapons and would depend on a central government. Filísola interpreted this as a delay, for which reason he declared the resolution null and claimed jurisdiction from the Empire; given the facts, the Salvadorans declared the incorporation into the Mexican Empire null and agreed to the incorporation into the United States on December 2. The declaration did not stop Filísola, who after occupying Mejicanos, on February 9, 1823, took San Salvador. There he had contact with Salvadoran leaders, including Delgado, who ended up confined to one of his farms. Despite the events, Iturbide abdicated the throne on March 19, so Filísola decided to convene the congress established in the minutes of September 15.

Central American Civil War

After Filísola's call, the Salvadoran province appointed its representatives. For San Salvador, José Matías Delgado and José Antonio Jiménez y Vasconcelos were elected as proprietary deputies, and Pedro José Cuellar and Juan Francisco Sosa as substitutes. On June 24, 1823, the Constituent Assembly of Central America was installed and the same Delgado was elected as its president with a total of thirty-seven votes. The first session was held on June 29, and Delgado gave a speech that reads in part:

In addition, Delgado, together with José Simeón Cañas, Pedro Molina Mazariegos, Francisco Flores and Felipe Vega, had issued the opinion regarding the absolute independence of the provinces of the Kingdom of Guatemala. Absolute Declaration of Independence of Central America, which at its beginning proclaims the name of "the United Provinces of Central America...";

However, in the new States the system that would govern the new Central American republic was debated, that is, between a federal or a centralized one. The prevailing opinion in the provinces, with the exception of Guatemala, was the federal system similar to that of the United States. The soldier and historian Manuel Montúfar y Coronado attributed the definitive adoption of this system to priest Delgado, accusing him of seeking personal benefit to erect the episcopal chair in San Salvador, although Meléndez Chaverri stressed that the attitude of Salvadorans "in their struggles libertarians was more than mobile enough for the adoption of a system for which they dreamed since 1811".

Delgado, Pedro Molina Mazariegos, José Francisco Barrundia, and Mariano Gálvez participated in the drafting of the Bases of the Federal Constitution published on December 17, 1823. With the installation of the Federal Republic of Central America, General Salvadoran Manuel José Arce was elected as its president for the year 1825. But in October 1826 the president of the Federal Republic of Central America, Manuel José Arce dissolved Congress and the Senate and tried to establish a unitary system by allying with the conservatives, so he was left without the support of his party, the liberal. Thus began a civil war in the region from which the dominant figure of Honduran General Francisco Morazán emerged.

Mariano de Aycinena y Piñol was appointed on March 1, 1827 as governor of the state of Guatemala by the president of the Federation of the United Provinces of Central America, Manuel José Arce. His governance was of a dictatorial nature; he prohibited the freedom of the press and the entry of liberal-type books into Guatemala. He also decreed the death penalty with retroactive effect and formed the fatal decree of 1827 for summary trials. As a member of the Conservative Party, he reinstated the obligatory tithes for the secular clergy of the Catholic Church.

Miniature portraits by the artist Francisco Cabrera of the ladies who belonged to the Aycinena Clan date from this period.

Ladies of the Aycinena Clan portrayed by Cabrera in the 1820s

Liberal invasion of Morazán in 1829

Morazán kept fighting around San Miguel, defeating each platoon sent by Arzú from San Salvador until he left Colonel Montúfar in charge of San Salvador and went to personally deal with Morazán; when the Honduran became aware of Arzú's movements, he left for Honduras to recruit more troops. On September 20, General Arzú was near the Lempa River with five hundred men in search of Morazán, when he learned that his forces they had capitulated in Mejicanos and San Salvador.

Meanwhile, Morazán returned to El Salvador with a respectable army. General Arzú, feigning illness, fled to Guatemala, leaving his troops under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Antonio de Aycinena. The colonel and his troops were marching towards Honduran territory, when they were intercepted by Morazán's men in San Antonio. On October 9, Aycinena was forced to surrender. With the capitulation of San Antonio, El Salvador was finally free of federal troops. On October 23, General Morazán made his triumphal entry into the Plaza de San Salvador. A few days later, he marched in Ahuachapán, to organize the army with a view to removing the aristocratic and ecclesiastical conservatives from power in Guatemalan territory and to establish a constitutional order similar to the Central American Federation that the liberals aspired to.

Upon learning of these facts, Mariano de Aycinena tried to negotiate with Morazán, but since he was determined to end the hegemony of the Guatemalan aristocrats and ecclesiastics, he did not accept any deal. Aycinena, seeing that he could not find a peaceful solution, wrote to his fellow citizens:

COMPATRIOTATIONS: With the greatest feeling, I see the need to announce to you: that all the efforts of the supreme national government, and of the authorities of the State, for the restoration of peace, have been useless: those who carry the voice and have taken over the command in S. Salvador, have an interest in prolonging the war; for it serves their personal views, and cares very little about the fate of the peoples. Inspiring to the domination of the whole republic, and to the increase of its own fortune, they want to dye the privileged soil with blood, and to destroy all the sources of the wealth of the nation and the particular owner. —Mariano de Aycinena y Piñol Manifesto of the Head of State to the peoples 27 October 1828 |

In Ahuachapán, Morazán did his best to organize a large army. He asked the government of El Salvador to provide him with four thousand men, but had to settle for two thousand. When he was able to act in early 1829, he sent a division under Colonel Juan Prem to enter Guatemalan territory and take control of Chiquimula. The order was carried out by Prem despite the resistance offered by the enemy. Shortly thereafter, Morazán moved a small force near Guatemala City under the command of Colonel Gutiérrez to force the enemy out of their trenches and cause his troops to desert. Meanwhile, Colonel Domínguez, who had left Guatemala City with six hundred infantry to attack Prem, learned of the small force Gutiérrez counted. Domínguez changed his plans and Gutiérrez went after him. This opportunity was taken advantage of by Prem, who moved from Zacapa and attacked Domínguez's forces, defeating them on January 15, 1829. After these events, Morazán ordered Prem to continue his march with the 1,400 men under his command and occupy the post of San José, near the capital.

Meanwhile, the people of Antigua Guatemala organized against the conservative government of Aycinena in Guatemala which hastened Morazán's invasion of Guatemala with his "Protector of the Law Army"; The Honduran placed his men in the town of Pínula, near Guatemala City. On February 15, one of Morazán's largest divisions, under the command of Cayetano de la Cerda, was defeated in Mixco by federal troops, so Morazán lifted the siege of the city and concentrated his forces in Antigua. A division of federal troops had followed him from the capital under the command of Colonel Pacheco, in the direction of Sumpango and Tejar with the purpose of attacking him in Antigua. But Pacheco extended his forces, leaving some of them in Sumpango. When he arrived at San Miguelito on March 6, with a smaller army, he was defeated by General Morazán,

After the victory at San Miguelito, Morazán's army grew when Guatemalan volunteers joined his ranks. On March 15, when Morazán and his army were on their way to occupy their previous positions, he was intercepted by Colonel Prado's federal troops at the Las Charcas ranch. Morazán, with a superior position, crushed Prado's army. The battlefield was left littered with corpses, prisoners and weapons. Subsequently, Morazán moved to recover his old positions in Pínula and Aceytuno, and again lay siege to Guatemala City. On March 18, 1829, Aycinena ordered that the death penalty be applied to anyone who helped the enemy, he made a proclamation in which he invoked the defense of the "sanctity of the altars" and issued a legal provision, by which the liberal leaders, including Dr. Pedro Molina Mazariegos, were declared enemies of the country; despite everything, he was defeated.

On April 12, 1829, he signed the Capitulation Agreement with Morazán and was sent to prison with his fellow government officials; Morazán, for his part, annulled the document on the 20th of the same month, since his main objective was to eliminate the power of the conservative Creoles and the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in Guatemala, whom the liberal crillos detested for having been under their domination. during the Spanish colony.

Government of Mariano Gálvez

After the separation of the Iturbide Empire, the Federal Republic of Central America was created, with Manuel José Arce as its first president. The Federal Republic was a political entity that included Guatemala, Comayagua, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica.

In 1837, an armed struggle began in the State of Guatemala against the person who governed the State of Guatemala, a liberal like Francisco Morazán, Dr. José Mariano Gálvez. Gálvez, a cultured and progressive liberal, had undertaken a series of social reforms aimed at undermining the power of the regular clergy, the main member of the Conservative Party along with the Aycinena Clan. He canceled the tithes, promulgated the divorce law and eliminated many of the privileges of the convents; Unsurprisingly, the secular clergy—who had not been expelled in 1829—presented the reforms not as an attack on the economic interests of the Church, but as an affront to the Christian faith, and stirred up the peasant population against the government. "heretic".

Pushed by liberal reforms and conservative propaganda, insurgent movements began in the mountains of Guatemala and Rafael Carrera y Turcios was their top leader; Among the rebellious troops were numerous indigenous people who fought for two years to achieve the Guatemalan secession from the federation, which was achieved in 1838 with the dissolution of the federation. The uprisings began by assaulting the towns, without giving them the opportunity to meet with government troops and propagating the idea of Gálvez's enemies, which consisted of accusing him of poisoning river waters to spread morbus cholera the population. This accusation favored Carrera's objectives, turning a large part of the population against Mariano Gálvez and the liberals; even the liberals themselves began to attack Gálvez for his violent military methods—including scorched earth tactics on uprising towns.

Independence of Los Altos

The Los Altos area was populated mostly by indigenous people, who had maintained their ancestral traditions and their lands in the cold highlands of western Guatemala. Throughout the colonial era there had been revolts against the Spanish government. independence, the local mestizos and criollos favored the liberal party, while the indigenous majority was in favor of the Catholic Church and, therefore, conservative.