Guadalquivir

The Guadalquivir River (from Arabic الوادي الكبير al-wādi al -kabīr, «the big river»)[citation needed], formerly called river Betis, is a river in Spain, whose course runs through Andalusia.

Since ancient times its source has been located in the Sierra de Cazorla, province of Jaén. Its hydrographic basin covers territories of the provinces of Almería, Jaén, Córdoba, Seville, Huelva, Cádiz, Málaga, Granada, Murcia, Albacete, Ciudad Real and Badajoz. It flows into the Atlantic Ocean in a wide estuary between Almonte (Huelva) and Sanlúcar de Barrameda (Cádiz province). Between Seville and the estuary there is a large wet area, the Guadalquivir marshes; Part of these marshes are within the Doñana National Park.

It is the fifth river by length of the Iberian Peninsula. It has 657 km from the Sierra de Cazorla to Sanlúcar. On its route through Andalusia from east to west, it crosses cities such as Andújar, Córdoba or Seville. Since pre-Roman times it was known as Baetis or Betis, and was called Wad al-Kibir by the Arabs from the 11th century.

Historical names

The second name he adopted was Baetis or Baitis. This name is of uncertain pre-Roman origin, and may have been formed from a Celtic, Iberian, or Ligurian root. The root baet or baes was present in Spain, France and Belgium. Through this root place names, names of tribes and names of gods were formed. Among these terms were Baeturia, Baetulo, Baetera, Baetorix, Baetasii, Baesisceris, Baesadines, Basippo, Besilus, Besaro, Baesula, Baecila, Baesucci, Baesella, Baeserte, etc. From this root come some current place names widely known as Baeza, Béziers, Besós, Bailén, Besalú and Úbeda. Some studies hold that the Phoenicians named the river Betsi, which is a Canaanite word.

Around VII century B.C. C. Greek navigators began to arrive who called it the Tharsis River, in reference to the kingdom of Tartessos. However, the Tartessians themselves continued to call their central river Baetis. The Romans would later conquer the region from the Carthaginians and the name remained, without any modification, Baetis or Betis. And, although the name remained unchanged since pre-Roman times, some authors referred to the river by other names, such as Stephen of Byzantium, who called it Perkes or Perci, or Tito Livio, who called it Certis.

According to another theory, Baetis would not be the true Tartessian name of the river, but what Tharsis would be, Baetis being a Greco-Roman transliteration resulting from confusing the Tartessian T and R with the Greek beta and delta, visually very similar. This would have resulted in Badsis, later corrupted to Baitis.

Although the Arabs were relatively respectful of local names, when the capital was established in Córdoba the river was called Nahr Qurtuba (Córdoba River) since the time of Rasis. In the XI century, the revolutionary fitna sank the Caliphate of Córdoba and this name began to decline and The classic Arabic word to refer to a river (nahr) is being replaced by a more current one: wad. Wad comes from wed, which was what the large boulevards were called in the Sahara and in the Maghreb. Then it came to be called the Grande River, which is Wad al-Kabir. Al-Kabir comes from a well-known Spanish-Arabic phenomenon like the "imāla", which turns Kibir into Kabir. When Ferdinand III arrived in Seville in the XIII century, the river was already known as Guadalquebir or Guadalquibir, which in the current spelling it is Guadalquivir.

Curiously, Idrisi, on his world map of 1154, names the river Nahr Agtam. On the other hand, other Arab authors such as Ibn Abd Rabbihi or Ibn al-Khatib call it the "Seville river".

Tributaries

The main characteristic of the tributaries of the Guadalquivir is the great difference between those on both banks, which are an expression of the considerable geographical differences that exist between the Sierra Morena and the Betic mountain ranges.

The tributaries of the Guadalquivir on the left bank have much more distance than those on the right bank, in fact the Genil is the longest tributary in Spain. In general, they have a southeast-northwest orientation and run through the Baetic mountain ranges to the great collector, crossing wide countryside.

On the right bank, the tributaries, known as mariánicos, present a loosely articulated network. Rather, they are independent courses with a certain equidistance that run towards the same collector. They start from peniplanadas summits of the Iberian massif and descend by the flanks of Sierra Morena with a channel very embedded in its hard materials.

Fluvial regime

The rainfall regime in the headwaters has a maximum in winter that is general throughout the basin. Snowmelt in the mountains, which takes place in spring, also contributes a significant amount of water to the river flow. The irregularity is 5.1 at the head and 3.40 at the mouth.

The floods of the Guadalquivir have caused problems throughout history, especially in the province of Seville, in the middle of the alluvial plain. In Seville, the river often overflowed its banks, flooding large areas of the old town and the Triana neighborhood. In the XX century alone, the Guadalquivir overflowed 18 times: 1902, 1910, 1912, 1915, 1917, 1920, 1924, 1926, 1927, 1929, 1930, 1932, 1934, 1936, 1937, 1939, 1940 and 1947, so it was finally decided to divert the river and leave the old channel as a dock. Thus, the problem of flooding has been resolved in the Andalusian capital, but not in Córdoba and other towns in the basin such as Andújar, Montoro and Lora del Río, affected by floods in December 1996, December 1997 and February and December 2010. The strongest flood of the 20th century was that of February 1963 with a flow of 5,400 m³/s in Córdoba and 6,700 m³/s in Seville. The regulation of the river, as well as all its tributaries, has prevented flows of this magnitude from being reached again. After the construction of the large reservoirs, the floods of December 1996 and 1997 stand out, in which Seville reached 3,810 m³/s and 3,234 m³/s respectively. More recently, in the February 2010 flood, the Guadalquivir reached 2,400 m³/s in Córdoba and 3,174 m³/s in Seville. In December 2010, due to the flood of its main tributary, the Genil, which exceeded 1,000 m³/s, the flow in Seville was 3,584 m³/s.

Reservoirs

There are 57 reservoirs in the Guadalquivir basin. Those that house more than 100 hm³ are the following:

| Embalse | Rio | Location/en | Province | Capacity (hm3) | Year of construction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aracena | Rivera de Huelva | Puerto Moral, Aracena and Zufre | Huelva | 127 | 1969 |

| Arenous | Arenous | Montoro | Córdoba | 167. | 2008 |

| Baby | Baby | Hornachuelos | Córdoba | 342 | 1963 |

| The Paint | Viar | Cazalla de la Sierra | Sevilla | 213 | 1948 |

| Giribaile | Guadalimar | Ibros and Vilches | Jaén | 475 | 1996 |

| Guadalén | Guadalén | Arquillos y Vilches | Jaén | 168 | 1958 |

| Guadalmellato | Guadalmellato | Adamuz, Obejo and Córdoba | Córdoba | 147 | 1928 |

| Guadalmena | Guadalmena | Chiclana de Segura, Segura de la Sierra y Orcera | Jaén | 347 | 1997 |

| Huesna | Huéznar | Constantine and El Pedroso | Sevilla | 135 | 1990 |

| Iznájar | Genil | Rute y Cuevas de San Marcos | Córdoba | 981 | 1969 |

| Jandula | Jándula | Come on. | Jaén | 322 | 1932 |

| José Torán | Guadalbarcar | Lora del Río | Sevilla | 113 | 1991 |

| Breña II | Guadiato | Almodóvar del Río | Córdoba | 823 | 2009 |

| La Fernandina | Guarrizas | Vilches | Jaén | 245 | 1991 |

| Montoro | Montoro | Solana del Pino and Mestanza | Ciudad Real | 105 | 2008 |

| Black | Guadiana Menor | Freila | Grenada | 567 | 1984 |

| New bridge | Guadiato | Villaviciosa de Córdoba | Córdoba | 282 | 1972 |

| Rumblar | Rumblar | Bathrooms of the Encina | Jaén | 126 | 1941 |

| San Clemente | Guardal | Huéscar | Grenada | 118 | 1990 |

| San Rafael de Navallana | Guadalmellato | Córdoba | Córdoba | 157 | 1991 |

| Tranco de Beas | Guadalquivir | Santiago-Pontons and Hornos de Segura | Jaén | 498 | 1948 |

| Yeguas | Yeguas | Montoro and Marmolejo | Córdoba | 229 | 1989 |

| Zufre | Rivera de Huelva | Zufre | Huelva | 175 | 1991 |

Course of the river

The Guadalquivir runs its course from east to west, turning south in the province of Seville. Most of the 657 km in length run through flat terrain called the Guadalquivir depression. The width of the river is about 10 m in Úbeda, 60 m in Córdoba and 330 m in its final stretch.

High Course

Most of the authors of Roman antiquity agreed that the Guadalquivir was born in the Sierra de Cazorla. A medieval tradition says that the Guadalquivir is born in the Cañada de las Fuentes within the Sierra de Cazorla, in municipality of Quesada, east of Jaén. In the XIX century, the politician and writer Pascual Madoz argued that the It was at the source of the Guadiana Menor. In the XX century, the historian Vicente González Barberán subscribed to the theory that the Guadalquivir was born where the Guadiana Menor, specifying its origin in the Cañada de Cañepla, Almería, near the border with Granada and Murcia. in the municipality of Peal de Becerro), which is indeed close to the source in Quesada.

Always in a NNE direction it crosses the Cerrada de los Tejos, El Raso del Tejar, La Espinareda, the Cerrada de los Cierzos and the Herrerías bridge. After passing by the Vadillo Castril, it pools briefly in the small reservoir of the Cerrada del Utrero at about 980 m s. no. m. It loses height in the Cerrada del Utrero and passes next to Arroyo Frío (La Iruela), crosses the bridge of Hacha and La Herradura to border the Cabeza Rubia hill and downstream receive the Borosa river on the right bank and a little further down the river Aguamulas, also by the same margin. It pools again in the extensive reservoir of the Tranco de Beas reservoir at 650 m s. no. m., where it turns to the west crossing the Sierra de Las Villas, next to Charco del Aceite it receives the María stream on the left and about three kilometers further down the Chillar stream also on the left, shortly after leaving the natural park of the Sierras de Cazorla, Segura and Las Villas.

After leaving this mountainous area, it reaches plains of olive groves 15 km from Úbeda. In this area it receives water from the Guadiana Menor and Jandulilla rivers. The Guadiana Menor flows into the Doña Aldonza reservoir and the Jandulilla between it and the Pedro Marín reservoir, next to the village of El Donadío (Úbeda). Upstream is the Puente de la Cerrada reservoir. These three reservoirs, the mouth of these two tributaries and the Guadalquivir are part of the Alto Guadalquivir Natural Area, which has 663 hectares. This Natural Area also covers part of the Sierra San Pedro and some agricultural land. The wetlands of this Natural Area are close to the Laguna Grande. It continues bordering La Loma to the south, and after the Puente del Obispo district (Baeza) it receives the river on the left bank Torres and further down to the right to the Guadalimar river.

The upper course, from its source to Mengíbar, has an extension of about 212 km and an average slope of 6.7 thousandths.

Intermediate course

Turning northwest, it passes next to Mengíbar, where it receives the Guadalbullón River on the left and next to Espeluy, after which it receives the Rumblar River on the right. Bordering Sierra Morena to the south, it passes next to Villanueva de la Reina and Andújar, after which it receives the Jándula river on the right. It passes next to Marmolejo and on the border of the province with Córdoba it receives the river Yeguas on the right.

To the north of the river is Sierra Morena. The fertile plains and countryside are much more extensive to the south and end in the Betic cordilleras.

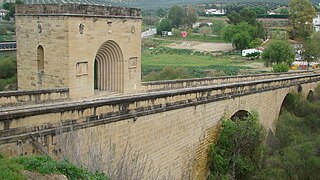

Later, the Guadalquivir meets Villa del Río and Montoro, after which it receives the Arenoso, Pedro Abad, El Carpio and Alcolea rivers on the right. Shortly before the latter, it receives the Guadalmilla River on the left, crosses Córdoba and receives the Guadajoz River on the left. In Almodóvar del Río it receives the Guadiato River on the right, passes through Posadas and receives the Bembezar River on the right. In Palma del Río it receives the Retortillo rivers, on the right, and the Genil rivers, on the left.

The middle course goes from Mengíbar to Peñaflor. This route is 247.8 km long and has an average slope of 0.73 thousandths

There is a region called Valle Medio del Guadalquivir that goes from Montoro to Alcalá del Río.

Low Course

The Guadalquivir river enters the province of Seville and passes through Peñaflor, Lora del Río, Alcolea del Río, Tocina and Cantillana, next to which it receives the Viar river from the right. It goes through Villaverde del Río, Brenes, Alcalá del Río, La Rinconada and La Algaba under which it receives the Rivera de Huelva river on the right and the artificial Tamarguillo riverbed on the left.

It passes through the west side of Seville. To the east, the river has a large basin where the Port of Seville is located and, at the end of it, there is a plug of land in the San Jerónimo neighborhood. It continues through Aljarafe, where it leaves Camas, San Juan de Aznalfarache and Gelves on the right, a town where there is a marina, and later on, it receives the Guadaíra river on the left.

Leaving Coria del Río and La Puebla del Río to the right, it is divided below these into several arms and semi-swampy areas called the marshes of the Guadalquivir, through which it passes through the last city of the province of Seville: the town of Lebrija. It enters the province of Cádiz through Trebujena, where the Esteros del Guadalquivir have been declared an Ecological Reserve. To the west is the Doñana National Park. Forming the dividing line between the provinces of Cádiz and Huelva, it flows into the Atlantic Ocean next to the municipalities of Almonte and Sanlúcar de Barrameda.

Works in the riverbed of the Lower Guadalquivir

From 1717 to 1815 the estuary was in charge of a Royal Consulate. In 1794 the Consulate obtained authorization from the Government to undertake some works. In 1795 the first cutting of the river was carried out, that of the Merlina. This was a project directed by Scipión Perosini. This cut was just over 500 meters and with it the Merlina lathe, about 10 km long, and the dangerous lowlands between Coria del Río and Dos Hermanas were avoided.

In 1815 the Guadalquivir Company was created and in 1816 work began on the Fernandina cut, to avoid the Borrego lathe, located upstream of Isla Menor. Its length was 1,700 meters and its layout was slightly curved, which reduced the riverbed by 16 km. The Company also has among its merits the creation of the first steamship in Spain, the Real Fernando Betis. After a series of unsuccessful projects by the Company, the Government decided to abolish it in 1852 and directly assume control of the projects. To do this, they commissioned a study to improve the estuary to the civil engineer Canuto Corroza, which was completed in 1857 and approved by the government in 1859. Although Corroza's study was not without erudition, it erred in the methods of execution, and The 4 years of works to carry it out greatly harmed the estuary and commerce, in addition to involving hard and useless work that generated great social unrest. However, from 1863 Manuel Pastor y Landero was in charge of the works, that he did act effectively, and after five years of work he managed to make the river reach a navigable draft of 5.18 meters.

In 1870 the government approved the Decree for the constitution of the Board of Works of the Port of Seville and the Guadalquivir river. In 1871 the regulations of this organization were approved by Royal Order. Its main work, until the beginning of the century XX, was to conserve and complete the facilities and projects. In 1880 the Jerónimos felling was finished, which was a straight alignment of 5230 meters and that replaced a winch of 13 km of development.

In 1902, the Basque engineer Luis Moliní Uribarri, then director of the Junta de Obras, drew up a project for the river to have a depth of 7 meters and to be a more effective way for ships to go from the ocean to the interior. For this, it was necessary to carry out works to improve the port, the estuary and the mouth. The works around the city would be the most ambitious. From 1909 to 1916 the Tablada cut was built, which reduced the route that the ships had to take to reach the port.

In 1926 the new route of the river was inaugurated by Alfonso XIII aboard the Argentine cruise ship Buenos Aires, where the crew of the seaplane Plus Ultra, who had crossed the river, were traveling. Atlantic.

Starting in 1929, the works plan of engineer José Delgado Brackenbury was put into operation. This would consist of creating a stopper in Chapina and letting the living river flow from the north, passing next to the San Jerónimo neighborhood and north of the Triana neighborhood. This produced a division between the neighborhood of Triana and the Cartuja. The works of the Brackenbury Plan were carried out in two phases: from 1929 to 1933 and from 1946 to 1950.

Works in the first half of the 20th century had turned the river as it passed through the center into a basin, although the new layout made it possible for San Jerónimo and Triana to be flooded, for which reason a long defense wall was also built.

Also in 1953, the government entrusted the port management with a preliminary project to improve the access channel to the Port of Seville. Three options were proposed, the third being an ambitious project. It consisted of digging a maritime channel located on the banks of the Guadalquivir to definitively abandon the natural course of the river for merchant ships. The channel would join the Port of Seville with a mouth in Bonanza. The Sevilla-Bonanza Canal project was drawn up in 1961, approved by the government in 1964 and construction began in December 1968, with completion expected in 1975. At this beginning, the Olivillos and La Isleta fellings were carried out. However, the project did not continue and currently appears to be off the table.

In 1983 an official was arrested for having stolen 10 million pesetas from the Junta de Obras.

In the works prior to the 1992 Universal Exposition, some fluvial works were carried out. The plug in Chapina was removed so that the basin would continue to the San Jerónimo park, where a new plug was found, and the live river now ran completely parallel to the basin to the west of the city. La Cartuja would be, in turn, almost surrounded by the dock and by the river, with a land connection to the south, in Triana, and another to the north, next to the north of the SE-30 or Ronda Supernorte, in the surroundings of the park of Saint Jerome.

Flora and fauna

Flora

Trees

Throughout the Guadalquivir basin, the southern holm oak (quercus rotundifolia), the black pine (pinus nigra), and the white poplar (populus alba). On the right bank and in the Betic mountain ranges, the strawberry tree (arbutus unedo) is common. The cork oak (quercus suber) is a tree present throughout Andalusia, although the large forests of this variety become more frequent from the middle channel and extend over large areas of Western Andalusia. In the upper channel, the Santa Lucía cherry (prunus mahaleb), the ash tree (fraxinus angustifolia) the chestnut tree (castanea sativa). the miera juniper (juniperus oxicedrus) is common. The hackberry (celtis australis) is a common tree around the Guadalquivir as it passes through the provinces of Córdoba and Seville. The jacaranda (jacaranda mimosifolia) is a species common throughout the Guadalquivir basin. Cinnamon (melia azedarach) is a very common species in the Guadalquivir basin from the middle channel.

The wild olive (olea europaea silvestris), the stone pine (pinus pinea), the black poplar (populis nigra), the false pepper tree (schinus molle), the ficus (phicus macrophylla), the palm (phoenix dactilifera), the acacia (acacia dealbata), the false acacia (robinia pseudoacacia), the plane tree (platanus hispanica) and the banana tree ( platanus) are trees that are present throughout Andalusia, including the Guadalquivir basin.

The olive tree is present throughout Andalusia. The orange tree (citrus aruantium) is present in Andalusia in the provinces of Huelva and Seville (sometimes next to the Guadalquivir) and in the province of Grenada.

Shrubs and Herbs

In Andalusia, and therefore in the Guadalquivir basin, the following species are frequent: rockrose (cistus ladanifer),, rosemary (rosmarinus officinalis), Maidenhair maidenhair (adiantum capillus-veneris), speedwell (veronica filiformis), marjoram (thymus mastichina), hawthorn (crataegus monogina) dandelion (taraxacun dens leonis), buckthorn (rhamnus alaternus) bramble (rubus fruticosus), sunflower (hielanthus annuus) gayomba (spartium junceum), yellow jasmine (jasminum fruticans),, lantana (lantana camera), snake (echium plantagineum), lady of the night (cestrum nocturnum), and carnation (dianthus caryophyllus).

The matagallo shrub is very frequent in the Guadalquivir basin from the middle channel, as well as throughout the Andalusian coast. Although the cow jaguar (cistus salvifolius) is present in several places in Andalusia (like Sierra Morena), as far as the Guadalquivir basin is concerned, it is only frequent in the sierra of its upper channel. Wild garlic (allium suaveolens) is present in the Guadalquivir basin from from the middle channel. The durillo shrub (viburnum tinus) is present in several places in Eastern Andalusia, and as far as the Guadalquivir basin is concerned, it is present in the upper and middle channels.

The cornicabra shrub (pistacia terebinthus) is present in the provinces of Jaén, Córdoba, Málaga and Granada. Its presence in the provinces of Jaén and Córdoba places it in the upper and middle channels of the Guadalquivir. in the middle course. It is also present in the mountains of Huelva and Málaga. On both sides of the middle and lower courses, and far from the channel, there are spaces where walling (anagallis arvensis) are common. typha latifolia) is very common in the lower riverbed and extends along the Cadiz and Huelva coasts. Heather (erica arborea) is present throughout Andalusia, with the exception of of the highest mountainous areas. The common mallow (malva silvestris) is present throughout Andalusia, except in mountainous areas and on the coasts.

The bindweed (convolvulus althaeoides) is present throughout the Guadalquivir basin, except in the areas closest to the mouth. In Andalusia, the spring grass (primura vulgaris) and saxifraga (saxifraga biternata) and the rascavieja shrub (adenocarpus decorticans) are present in the mountainous areas of the upper and middle sections of the Guadalquivir and, Outside of these environments, they can also be found in the Sierra de Málaga. In Andalusia, the blue flax (linum narbonense) is found far from the river in the upper and middle reaches, as well as in the east of the province of Almería. The common violet ( viola adorata) is present in the more mountainous areas that are left on the sides of the Guadalquivir and in the Sierra de Málaga. The tamarisk (tamarix africana) can be found throughout the basin of the river and throughout the Andalusian coast, with the exception of the coast of the province of Granada.

The oleander (nerium oleander) grows in Andalusia in the upper and middle channels of the Guadalquivir, as well as in Sierra Morena and in the Sierra de Huelva. It has been a species widely used in gardening.

Radicchio (cichorium intybus), meadow clover (trifolium pratense), and honeysuckle (lorichera perychemenum) They can be found throughout Andalusia, excepting only the east of the province of Almería.

The plumed hyacinth (muscari conosum) can be found south of the middle channel of the Guadalquivir and in the province of Almería. The rock bell (campanula velutina) It can be found throughout the north of Andalusia and throughout the east of the province of Jaén (which includes the upper reaches of the Guadalquivir), the north of the province of Granada and the west of the province of Almería.

Herba de vaca (vaccaria hispanica) is present in a wide strip that covers the north of the provinces of Seville, Cádiz and Málaga, the southeast of the province of Huelva, and the south of the province of Córdoba and the southwest of the province of Jaén.

In addition to the named species, other shrubby or herbaceous species typical of the Mediterranean climate can be found in the Guadalquivir basin.

Wildlife

Mammals

In the Doñana National Park and in the entire mountainous environment of the north of the Guadalquivir there are specimens of the Iberian lynx. In mountainous areas of the upper course and in the Sierra Morena, the ibex lives. mouflon. Throughout the northern part of Andalusia, including the part of the upper channel, there are weasels. In the upper and middle channel, as well as in the mountainous areas of northern Andalusia, the genet is present. The otter has its Habitat throughout the riverbed, although there are few specimens. In the upper riverbed the wolf is present. In the middle and upper riverbed the squirrel is present. In Doñana and in the upper and middle riverbeds the roe deer, the fallow deer and wild boar.

Birds

The Guadalquivir basin is a common place for observing different species of birds.

There are some species that, in this basin, can practically only be found in Doñana, such as the imperial eagle, the Malvasia, the flamingo and the stilt. The basin also includes endangered species, such as the aforementioned eagle imperial, the marbled teal, the Eurasian coot, the squacco heron, and the brown pochard. The griffon vulture, present in the basin, was in danger of extinction in the 1990s, but its population seems to have recovered in the entire peninsula.

The Eurasian Bittern was thought to be extinct as a breeder in the Lower Guadalquivir, although nests have been discovered since 2002.

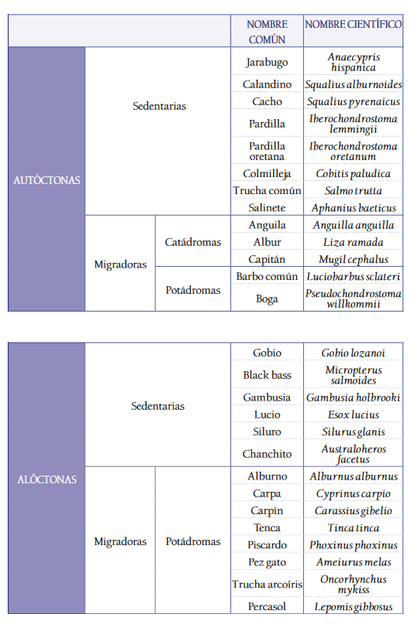

Fish

Among the best-known fish are the barbel and the river bream. In Andalusia we can find the barbel in the Guadalquivir and Guadiana basins. The shad is also found in the Guadalquivir and the Guadiana, although it is less frequent in the latter river. The river boga is a fish that can be found in many rivers and reservoirs in Andalusia and can reach about 24 centimeters.

The fartet, the saltpeter, the sturgeon, the sea lamprey and the jarabugo are practically extinct in this river.

The presence of various foreign species has reduced the number of endemic species in the Guadalquivir.

Economy

Trade

The Guadalquivir is an outlet from Western Andalusia to the Atlantic. Tartessos exported tin, which was shipped along the Andalusian coast and in the Guadalquivir., very good. Likewise, it exports wax, honey, fish, a lot of kermes and reddish.

In ancient times it was navigable up to its middle course. However, according to Strabón, from the current Alcalá del Río navigation had to be by boat. In Roman times trade was carried out on the river with amphoras full of different products. Wine and olive oil transported by this river reached other parts of the Empire. It was common for wine and oil to be taken to the ports of Puteoli and Ostia. In addition to the main port of Hispalis, there were also some docks and piers in the estuaries of Asta Regia (Mesas de Asta) and Nebrissa (Lebrija). The minerals extracted from Almadén, Río Tinto and Aznalcóllar were shipped on the Guadalquivir to Rome.

This trade with Rome, which peaked in the first and second centuries, declined from the III century, because of imperial decline. Exports from the Guadalquivir continued to decline as the High Middle Ages entered, until the Visigothic period.

With Fernando III, a body of boatmen was created that transported goods from Seville to Córdoba. These were known as the "barqueros de Córdoba". This was a group of about forty people who had their headquarters in Seville. oars that were between 7 and 10 meters long and shallow. Ferdinand IV, Alfonso XI and Pedro I established that those who owned mills (aceñas) and dams (azudas) on the Guadalquivir had to give way to boatmen. However, the tax privileges for the boatmen of Córdoba ceased with Pedro I. In addition, the nobles closed some fluvial canals built in their dominions. This, together with the difficulty of land communications, reduced trade between Córdoba and Seville. However, some shipments between Córdoba and Seville by boat continued during the century XV.

Between the 13th and XV Cereals, oil, wine, chickpeas, broad beans, scarlet, wool, skins, saffron, dyes, tanning substances, soaps, various metals and luxury objects were exported through the Port of Seville. carried out by Sevillian, Genoese, Biscayan, Catalan and Burgos merchants. The most exported product was oil, which was obtained in the countryside or in Aljarafe, put into barrels and taken to England, Flanders, Genoa, Lisbon, Chios and other places. The soap, produced in the Reales Almonas in Seville, was sent to Antwerp. Andalusian and Extremaduran wool was sent to Genoa. The wine produced in the Sierra Norte de Sevilla, the Alcores and the Aljarefe was sent to Ireland, Normandy and Brittany. The metal from Almadén was exported to Bruges, Genoa, Florence, Chios and Syria. In the 15th and 16th centuries the proportions of the shipments changed, as the population of Seville increased and the need to supply the ships that went to the Indies increased grain exports.

The royal asiento that gave Seville the monopoly of trade with the Indies between 1503 and 1717 increased the commercial volume of the port. The ships that arrived from America unloaded precious metals, pearls, leather, sugar, tallow, sarsaparilla, cotton, brazilwood, guayacán, indigo, precious woods, and other merchandise.

19th century is a project to create a channel for the river, never realized

Between the 1940s and the 1970s there was a great increase in trade with the Port of Seville, which is the only inland commercial port in Spain and is located 80 km from the mouth. Between 1941 and 1970, the Port of Seville imported and exported quantities of more than 100 tons with practically all the American and European countries with access to the sea, as well as with Australia, Japan and southern Africa. In the early 1960s exceeded 2,000,000 t with Europe. In 1946 it exceeded 150,000 t with Asia (although in the 1970s it had decreased to around 50,000 t). Since the 1940s, trade with America has only increased, reaching more than 1,300,000 tons in 1970. Trade with Africa increased from the 1940s from 100,000 t to 800,000 t in the 1960s, although in the 1970s it decreased to 600,000 t. Trade with Australia went from very low levels in the 1940s to over 3,000 tons in 1970.

The port of Seville has continued to grow at the end of the XX century and beginning of the XXI, both in infrastructure and in trade volume. In 2016 it reached 2.3 million tons. Among the shipments, those of cereals, flour and metals stand out.

Transportation of passengers and cruise ships

At the beginning of the XIX century, in 1817, the first steamship built in Spain was built in Triana, the Real Fernando, to link Seville with Sanlúcar de Barrameda, which reduced the navigation between the two towns from between eight and nine days due to the difficulty of sailing the Guadalquivir to only nine hours.

In the middle of the XIX century, thanks to the steamship, lines of passenger ships began to be created. These companies include Segovia, Cuadra y Compañía (to Marseille) (1858, refounded in 1892 as Compañía Sevillana de Navegación a Vapor), Ibarra y Compañía (to Bilbao) (1860), Vinuesa, Alcón y Compañía (to Marseille) (1861), Juan Cunningham y Compañía (to London) (1861), M. Sáenz y Compañía (to Liverpool) (1872), Casanovas y Compañía (Algeciras-Ceuta-Tetuán) (1863) and Ricardo Trías y Compañía (to Cádiz) (1871).

Currently, Seville is a stopover for tourist cruises.

Fishing

Historically (with data from the XIII century) the following species have been fished in the Guadalquivir: lamprey, tarpon, shad, picón, machuelo, alguila, zafio, snook, sollo (sturgeon), silverside and albur.

The construction of the Alcalá del Río dam in 1931 made it impossible for the reproductive migration upstream of anadromous species (salmonids, acipenserids and clupeids) that seek clean, oxygenated and running water to spawn, or those that live in the river during the pre-reproductive period (eel and silverside), which have been trapped upstream of the dam forming relict populations. The construction of this dam led to the virtual disappearance of the soll in the river in the 1970s. species was fished to obtain caviar in Coria del Río. At present, the Corianos continue to fish for the albur, flourishing around this fishing, a rich local gastronomy.

Between 1965 and 1966, black-bass or American perch were introduced into the basin for sport fishing, which transformed the fish community in the area.

At the end of the XX century, fishing for eel, red crab and shrimp. In 2011 the authorities prohibited the capture of eel because it is an endangered species. The red crab was introduced in 1974 and is an important source of income for Isla Mayor. In addition, it serves as food for many fishing birds.

In 2010, the endangered eel (Anguilla anguilla) was protected from illegal fishing, although its consumption is allowed.

Agriculture

In 2013 there were 883,083 hectares of irrigated crops in the Guadalquivir basin. Olive groves are widespread. In the Lower Guadalquivir, rice cultivation is frequent, of which there are more than 35,000 hectares.

In literature

The Guadalquivir is the most important river in Andalusia due to its length, its flow and the surface of its basin. For this reason, it has served as an inspiration for some writers who have passed through southern Spain.

Anacreon (560-478 BC) mentions the river in a stanza. -transform:lowercase">IV AD), Marcus Valerius Martial (I century AD).), Al Kutandi, Alfonso X el Sabio (13th century), Fray Luis de León (1527-1591), Juan de la Cueva (1606), the Marquis of Santillana (1388-1458), Gutierre de Cetina (1520–1554), Gonzalo Argote de Molina (1548-1608) and Juan de Mal Lara (1525-1571).

In the 15th century Jorge Manrique wrote Coplas on the death of his father, probably in Segura de la Sierra, which is a town linked to the upper course of the Guadalquivir. The best-known verses of this work say:

Our lives are the riverswho are going to stop the sea

that is to die

In the 17th century, Francisco de Quevedo wrote:

Naces Guadalquivir of pure sourceWhere your crystals, light the flight,

After he threw himself in hard rock

It twists the groundFrancisco de Quevedo

Also in the Golden Age, Luis de Góngora y Argote dedicated a couple of stanzas to it. In one of them he wrote:

Arroyo, what's to stop

so long and die,

you for being Guadalquivir,

Guadalquivir for being a sea?Fragment of the letrilla Against a private

Oh great river, great king of Andalusia,

Noble sands since not golden!Fragment of A Cordoba

In the XIX century it is mentioned in poems by Carlos Fernández Shaw and Adriano del Valle. In 1898 he was the inspiration for a poem called El Río by Vicente Aleixandre. In the XX century the river continued to be a source of inspiration for authors such as: Juan Rejano (1900), Mario López (1918), Fernando de los Ríos (1921), Antonio Luis Baena (1932), Arcadio Ortega Muñoz (1938), Pío Gómez Nisa, Manuel Lozano Hernández and Concha Lagos (1916). On a tombstone in Cañada de las Fuentes is written a poem by the Álvarez Quintero brothers that says:

Stop here traveler! Between these rocksHe is born and will be King of the rivers

That they ruin their birth and rough breñas

Between giant pines and gillsHermanos Álvarez Quintero

Antonio Machado, born in Seville, wrote several verses about the Guadalquivir, among which are the following:

Oh Guadalquivir!I saw you in Cazorla born;

Today, in Sanlúcar to die.A clear water borbollion,

under a green pine,

It was you, you sounded good!Like me, near the sea,

You dream of your spring?

Saloon River,Of the «Proverbs and Songs» of the book New songs

Image gallery

Administration

The management is in charge of the Guadalquivir Hydrographic Confederation, dependent on the State Government. The 2007 Statute of Autonomy gave the Junta de Andalucía the management of the river. However, this contravened the state regulations on hydrographic basins that covered several autonomous communities. For this reason, in 2011 the Constitutional Court annulled that article of the statute and the management returned to be in charge of the Guadalquivir Hydrographic Confederation.

Since 2009, 53 of the 57 reservoirs in the basin have been managed by the Junta de Andalucía. The Fresneda and Montoro reservoirs (both in the province of Ciudad Real) would remain in the hands of the State. The Jándula and Pintado reservoirs are jointly managed by the State and the Board. In 2010, the Board, due to lack of financial solvency, returned management to the State of La Breña II and Arenoso. With the 2011 ruling, all the reservoirs they were again in charge of the Guadalquivir Hydrographic Confederation.

Expansion Dredging

Dredging to extend the depth of the Guadalquivir River was planned between 2001 and 2013, although it was not finally carried out.

In 2001, the Seville Port Authority sent the complete file of the work to the General Directorate of Quality and Environmental Assessment. This matter was taken by the environmental organization WWF-Adena to the Administrative Litigation Chamber of the TS, which ordered a more detailed study. In general terms, the expansion of the dredging of the river consists of the deepening and widening of practically the entire navigable section of the Guadalquivir (86 kilometers, from Punta del Verde to the lower Salmedina). Currently the average draft of the river is 6.5 meters, but after this action it would be between 7.6 and 8 meters, depending on the sections. In other words, the bottom of the canal would be deepened by 1.5 meters. The base project also contemplates maintenance dredging for a period of 20 years.

An increase in the river's capacity could lead to an increase in the salinity of the channel, which could harm the crops of the Lower Guadalquivir. This was the main reason why the Ministry of Agriculture decided in 2013 not to undertake this expansion dredging.

Pollution

Starting in 1963, the WWF organization made a collection to buy land in Doñana (in the Lower Guadalquivir) and give it protection. Biologist José Antonio Valverde helped in the process of creating a national park. However, there is now an abundance of illegal wells.

Although great advances have been made since the end of the XX century, in 2007 it was recorded that 30% of the discharges that were made to the Guadalquivir were unrefined. Most of these discharges come from small municipalities or organic waste from the agricultural industry. The Guadalquivir Hydrographic Confederation processes many fines a year for this reason to municipalities and industries.

Environmental groups say that the mining and gas pipeline projects proposed in the area could constitute an attack against this environment. Guadalquivir caused an ecological catastrophe, which came to be called "the Aznalcóllar Disaster". Cleaning that environment cost 89 million euros, of which Bolidén ignored. For this reason, in the case of reopening the Aznalcóllar mine, the contract specifies that there is no sludge pool., which has ended in a judicial conflict.

Illicit trafficking

The Lower Guadalquivir is an entry point for hashish from North Africa. This has led the authorities to set up a checkpoint at the Port of Chipiona, next to the mouth.

Contenido relacionado

Antananarivo

Moscow

Annex: Municipalities of the province of Valladolid