Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the set of myths and legends belonging to the culture of Ancient Greece, dealing with their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, the origins and meaning of their own cults and ritual practices. They were part of the religion of Ancient Greece, whose object of worship was basically the Olympic gods. Modern researchers turn to myths and study them in an attempt to shed light on the religious and political institutions of ancient Greece and its civilization, as well as to better understand the nature of the myths' own creation.

Greek mythology appears explicitly in an extensive collection of stories and implicitly in figurative arts such as painted pottery and votive offerings. Greek myths attempt to explain the origins of the world and detail the lives and adventures of a wide variety of gods, heroes, and other mythological creatures. These stories were originally spread in an oral poetic tradition, although today the myths are mainly known from Greek literature.

The oldest known literary sources, the epic poems of the Iliad and the Odyssey, focus on the events surrounding the Trojan War. Two poems by Homer's near-contemporary Hesiod, the Theogony and the Works and Days, contain accounts of the genesis of the world, the succession of divine rulers and human epochs, and the origin of human tragedies and sacrificial customs. Myths were also preserved in the Homeric hymns, in fragments of epic poetry of the Trojan cycle, in lyric poems, in the works of the playwrights of the 5th century BC. C., in writings by researchers and poets of the Hellenistic period and in texts from the time of the Roman Empire by authors such as Plutarch and Pausanias.

Archaeological finds provide an important source of detail about Greek mythology, with gods and heroes featured prominently in the decoration of many objects. Geometric designs on pottery from the 8th century BC. C. represent scenes from the Trojan cycle, as well as adventures of Heracles. In the subsequent Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic periods mythological scenes from Homer and various other sources appear to supplement existing literary evidence.

Greek mythology has exerted a wide influence on the culture, art, and literature of Western civilization and remains a part of Western cultural heritage and language. Poets and artists have found inspiration in it from ancient times to the present day and have found contemporary significance and relevance in classical mythological themes.

Sources of greek mythology

Greek mythology is known today primarily from Greek literature and mythical representations on plastic media dated from the Geometric period (about 900-800 BC) onwards.

Literary sources

Mythical stories play an important role in almost all genres of Greek literature. Despite this, the only conserved general mythographic manual from Greek antiquity was the Mythological Library of Pseudo-Apollodorus. This work attempts to reconcile the conflicting stories of the poets and provides a great summary of traditional Greek mythology and heroic legends. Apollodorus lived between c. 180-120 BC C. and wrote on many of these subjects, but nevertheless the Library discusses events that took place long after his death, and hence the name Pseudo-Apollodorus.

Among the oldest literary sources are Homer's two epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Other poets completed the 'epic cycle', but these later minor poems are almost entirely lost. Apart from its traditional name, the Homeric hymns have no direct relation to Homer. They are choral hymns from the oldest part of the so-called lyrical age.

Hesiod, a possible contemporary of Homer, offers in his Theogony ('Origin of the gods') the most complete account of the first Greek myths, dealing with the creation of the world, the origin of the gods, the Titans and the Giants, including elaborate genealogies, folktales, and etiological myths. Hesiod 's Works and Days, a didactic poem on agricultural life, also includes the myths of Prometheus, Pandora, and the four ages. The poet gives advice on how best to succeed in a dangerous world made even more dangerous by his gods.

Lyric poets often took their themes from myth, but the treatment became less narrative and more allusive. Greek lyric poets, including Pindar, Bacchylides, and Simonides, and bucolics, such as Theocritus and Bion, recount individual mythological events. Additionally, myths were crucial to classical Athenian drama.

The tragic playwrights Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides took most of their plots from the Age of Heroes and the Trojan War. Many of the great tragic stories (such as Agamemnon and his sons, Oedipus, Jason, Medea, etc.) took their classical form in these tragic plays. The comic playwright Aristophanes also used myths, in The Birds and The Frogs.

The historians Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus and the geographers Pausanias and Strabo, who traveled throughout the Greek world and collected the stories they heard, provide numerous local myths and legends, often giving little-known alternative versions.

In particular, Herodotus searched for the various traditions that presented themselves to him and found the historical or mythological roots in the confrontation between Greece and the East, trying to reconcile the origins and mixtures of different cultural concepts.

The Fabulae and De astronomica of the Roman writer known as Pseudo-Hyginus are two important non-poetic compendiums of myths. Two other useful sources are the Pictures of Philostratus the Younger and the Descriptions of Callistratus.

Finally, Arnobius and several Byzantine writers provide important details of myths, many of them from earlier Greek works now lost. These include a lexicon of Hesychius, the Suda, and the treatises of John Tzetzes and Eustathius.

- Main authors

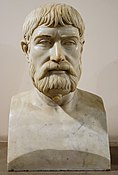

Bust of Homer, author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, two epic works whose writings narrate the interaction of gods and humans.

Bust of Homer, author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, two epic works whose writings narrate the interaction of gods and humans.The historian Herodotus, considered the father of History, and whose Histories are preserved, written during the 5th century BC. c.

Hesiod, author of the Theogony (8th century BC), a genesis of the origin of the cosmos and the gods

Hesiod, author of the Theogony (8th century BC), a genesis of the origin of the cosmos and the gods Pindar, lived during the sixth century BC. C. he It was he who advised "sow with hands full, not bags full"

Pindar, lived during the sixth century BC. C. he It was he who advised "sow with hands full, not bags full"

The moralizing point of view about the Greek myths is summed up in the saying ἐν παντὶ μύθῳ καὶ τὸ Δαιδάλου μύσος en panti muthōi kai to Daidalou musos ('in every myth there is the desecration of Daedalus'), about which the Suda alludes to the Daedalus' role in satisfying Pasiphae's "unnatural lust" for Poseidon's bull: "Since the origin and blame of these evils were attributed to Daedalus and he was hated by them, he became the subject of the proverb.

Under the influence of Homer the heroic cult led to a restructuring of the spiritual life, expressed in the separation of the realm of the gods from the realm of the dead (heroes), that is, the chthonics from the Olympians. In the Works and daysHesiod makes use of a scheme of four ages of man (or races): golden, silver, bronze and iron. These races or ages are separate creations of the gods, the golden age corresponding to the reign of Cronus and the following races being the creation of Zeus. Hesiod inserts the age (or race) of the heroes right after the Bronze Age. The last age was the iron age, during which the poet himself lived, who considered it the worst and explained the presence of evil through the myth of Pandora, who poured out of the jar all the best human characteristics except hope . metamorphosis Ovid follows Hesiod's concept of the four ages.

We must also mention the contribution of the poetry of the Hellenistic and Roman eras, although they were works composed as literary rather than cultural exercises. However, they contain many important details that would otherwise have been lost. This category includes works by:

- The Greek poets of late antiquity Nonus, Antoninus Liberal, and Quintus of Smyrna.

- The Greek poets of the Hellenistic period Apollonius of Rhodes, Callimachus, Pseudo-Eratosthenes and Parthenius.

- Ancient novels by Greek and Roman authors such as Apuleius, Petronius, Lollian, and Heliodorus.

- The Roman poets Ovid, Statius, Valerius Flaccus, Seneca, and Virgil, with Servius' commentary.

Archaeological sources

The discovery of the Mycenaean civilization by the German amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann in the 19th century and the discovery of the Minoan civilization on Crete by the British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans in the 20th century helped to explain many existing questions about Homer's epics and provided archaeological evidence for many of the mythological details about gods and heroes.

Unfortunately, the evidence for myth and ritual at the Mycenaean and Minoan sites is quite monumental, as the Linear B inscriptions (an ancient form of Greek found in both Crete and Greece) were used primarily to record inventories, although the names of gods and heroes have dubiously been revealed.

Geometric designs on pottery from the 8th century B.C. They depict scenes from the Trojan cycle, as well as the adventures of Heracles. These visual representations of the myths are important for two reasons: on the one hand, many Greek myths are attested on vessels rather than in literary sources (for example, from the twelve works of Heracles only the adventure of Cerberus appears in a contemporary literary text), and on the other the visual sources sometimes represent myths or mythical scenes that are not collected in any preserved literary source.

In some cases, the first known representation of a myth in geometric art predates its first known representation in late archaic poetry by several centuries. In the Archaic (c. 750–500 BC), Classical (c. 480–323 BC) and Hellenistic Homeric scenes and several others appear to supplement existing literary evidence.

Mythic chronology

Epic poetry created historical cycles and consequently developed a mythological chronology. In this way Greek mythology unfolds as a phase in the development of the world and man. Although the self-contradictions of these stories make an absolute timeline impossible, an approximate chronology can be discerned. The mythological history of the world can be divided into three or four great periods:

- The myths of origin or age of the gods (theogony, 'births of the gods'): myths about the origins of the world, the gods and the human race.

- The Age When Men and Gods Mixed Freely: Stories of the Early Interactions Between Gods, Demigods, and Mortals.

- The age of heroes (heroic age), where divine activity was more limited. The last and greatest heroic legends are those of the Trojan War and its aftermath (considered by some researchers to be a separate fourth period).

While the age of the gods has often been of more interest to contemporary mythologists, Greek authors of the archaic and classical eras had a clear preference for the age of heroes, establishing a chronology and recording human achievement with the ages of the heroes. to answer questions about how the world was created. For example, the heroic Iliad and Odyssey dwarfed the Theogony and the Homeric hymns in both length and popularity.

Origin of the cosmos and the gods

Cosmogony and cosmology

The "origin myths" or "creation myths" represent an attempt to make the universe understandable in human terms and to explain the origin of the world. The most widely accepted version at the time, albeit a philosophical account of the beginning of things, is the collection by Hesiod in his Theogony. It begins with Chaos, a deep emptiness. From this emerged Gaia (the Earth) and some other primordial divine beings: Eros (Love), the Abyss (Tartarus) and Erebus.

Without male help, Gaia gave birth to Uranus (Heaven), who then fertilized her. From this union the Titans were born first: Oceanus, Ceo, Crius, Hyperion, Iapetus, Tea, Rhea, Themis, Mnemosyne, Phoebe, Tethys and Crono. After this, Gea and Uranus decreed that no more titans would be born, so that the one-eyed Cyclopes and the Hecatonchires or Centimanos followed. Cronus, "the youngest, twisted-minded, most terrible of Gaia's sons", prompting Gaea's complaints, he castrated his father and became ruler of the gods with his sister and wife Rhea. as his consort and the other Titans as his court. Generally, the Greek tradition indicates that from this castration, Aphrodite arose, emerging from the sea, after her father's testicles fell into the ocean.

The theme of father-son conflict was repeated when Cronus clashed with his son, Zeus. Having betrayed his father, Crono feared that his offspring would do the same, so every time Rhea gave birth to a child, he kidnapped and swallowed them. Rhea hated him and tricked him by hiding Zeus, the last of his sons, and wrapping a stone in swaddling clothes, which Cronus swallowed. Rhea raised Zeus on Mount Ida in Crete, being fed by a goat, when Zeus grew up, he gave his father a poison that forced him to vomit his brothers and the stone, which had remained in Crono's stomach all the time..

Titanomachy and division of powers on Earth

Zeus fought against his father, Cronus, for the throne of the Earth, for which a war of gods against titans was unleashed. Along with his brothers Poseidon and Hades and sons (later members of the Olympian pantheon) with the help of the Cyclops (whom he freed from Tartarus) who gave each brother a weapon, Zeus and his brothers achieved victory, condemning Cronus and the Titans imprisoned in Tartarus, the center of the Earth.

In this way they ensured control over the Earth, which was divided into three kingdoms: the trinity consisted of Heaven for Zeus, the ocean for Poseidon, and the underworld for Hades, who guards the Titans from leaving Tartarus.

Zeus suffered the same concern and, after it was prophesied that his first wife Metis would give birth to a god "greater than himself", he swallowed her. However, Metis was already pregnant with Athena and this saddened him until she sprouted from her head, adult and dressed for war. This "rebirth" of Athena was used as an excuse to explain why he was not overthrown by the next generation of gods, while also explaining her presence. It is likely that the cultural changes already in progress absorbed the entrenched local cult of Athena in Athens into the shifting Olympian pantheon without conflict because it could not be overthrown, since he and his brothers and his children fought together.

Ancient Greek thought about poetry regarded theogony as the prototypical poetic genre—the prototypical mythos — and attributed almost magical powers to it. Orpheus, the archetypal poet, was also the archetypal singer of theogony, which he used to calm seas and storms in Apollonius's Argonautics, and to stir the stony hearts of the gods of the underworld on their descent into Hades. When Hermes invents the lyre in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, the first thing he does is sing the birth of the gods.

Hesiod 's Theogony is not only the most complete surviving account of the gods, but also the most complete surviving account of the archaic role of the poets, with its long preliminary invocation of the Muses. The theogony was also the subject of many now-lost poems, including those attributed to Orpheus, Museo, Epimenides, Abaris, and other legendary seers, which were used in private purification rituals and mystery rites.

There are indications that Plato was familiar with some version of the Orphic theogony. However, silence about these religious rites and beliefs was expected, and members of the sect would not speak about their nature as long as they believed in them. After they ceased to be religious beliefs, few knew about these rites and rituals. There were often allusions, however, to aspects that were quite public.

There were images on ceramics and religious works that were interpreted or more likely misinterpreted in many different myths and legends. A few fragments of these works are preserved in quotes from Neoplatonic philosophers and recently unearthed papyrus fragments. One of these fragments, the Derveni Papyrus, now shows that at least in the 5th century BC. C. there was a theogonic-cosmogonic poem of Orpheus. This poem attempted to supersede Hesiod's Theogony and extended the genealogy of the gods with Nix (Night) as a definitive beginning before Uranus, Cronus and Zeus. Night and Darkness could be equated with Chaos.

The early philosophical cosmologists reacted against, or sometimes drew on, popular mythical conceptions that had existed in the Greek world for some time. Some of these popular conceptions can be deduced from the poetry of Homer and Hesiod. In Homer, the Earth was seen as a flat disk floating on the river of Oceanus and dominated by a hemispherical sky with sun, moon, and stars.

The Sun (Helios) crossed the heavens like a charioteer and sailed around the Earth in a golden cup at night. Prayers could be addressed and oaths sworn by the sun, the earth, the sky, the rivers and the winds. Natural fissures were popularly considered entrances to the subterranean abode of Hades, home of the dead.

The greek pantheon

According to classical mythology, after the overthrow of the Titans, the new pantheon of gods and goddesses was confirmed. Among the main Greek gods were the Olympians, residing on Olympus under the aegis of Zeus. Among the most important, in addition to Zeus, are Poseidon, Hades, Apollo, Athena, Artemis, Aphrodite, Ares, Dionysus, Hestia, Hermes, Hephaestus and Hera.

When these gods were alluded to in poetry, prayer, or worship, it was by a combination of their name and epithets, which identified them by these distinctions from the rest of their own manifestations. Alternatively the epithet may identify a particular or local aspect of the god.

Most of the gods are related to human and specific aspects of life (mostly include the western zodiac). For example, Aphrodite was the goddess of love and beauty, while Ares was the god of war, Hades the god of the dead, and Athena the goddess of wisdom and strategy. Some deities such as Apollo (god of music) and Dionysus (god of wine), revealed more complex personalities and various functions, while Hestia literally means 'home'.

Apart from these, the Greeks worshiped various gods, considered secondary. The muses of Apollo, linked to knowledge and the fine arts. The rustic demigod Pan, the nymphs, naiads (who lived in the fountains), dryads (in the trees) and nereids (in the sea), oceanids, satyrs and others.

In addition, there were dark powers from the underworld, such as the Erinyes (or Furies), who were said to persecute those guilty of crimes against kin. To honor the ancient Greek pantheon, poets composed the Homeric hymns (a set of 33 songs). Gregory Nagy regards "the longest Homeric hymns as mere preludes (compared to the Theogony), each of which invokes a god".

In the wide variety of myths and legends that make up Greek mythology, the deities that were native to the Greek peoples were described as essentially human but with ideal bodies.

According to Walter Burkert, the defining characteristic of Greek anthropomorphism is that "the Greek gods are persons, not abstractions, ideas, or concepts." Regardless of their essential forms, the ancient Greek gods have many fantastic abilities, the most important being that they are immune to disease and can be injured only under highly unusual circumstances.

The Greeks considered immortality as a distinguishing characteristic of the gods; immortality that, like his eternal youth, was ensured through the constant use of nectar and ambrosia, which renewed the divine blood in his veins.

Each god descends from his own genealogy, pursues different interests, has a certain area of his specialty, and is guided by a unique personality; however, these descriptions emanate from a multitude of archaic local variants, which do not always coincide with each other.

The most impressive temples tended to be dedicated to a limited number of gods, who were the center of large Pan-Hellenic cults. It was, however, common for many regions and populations to dedicate their own cults to lesser gods. Many cities also honored the better-known gods with distinctive local rites and associated strange myths unknown elsewhere. During the heroic age, the cult of heroes (or demigods) supplemented that of the gods.

The Age of Gods and Mortals

Bridging the age when the gods lived alone and the age when divine interference in human affairs was limited was a transitional age when gods and mortals mixed freely. These were the early days of the world, when groups mixed more freely than they would later. Most of these stories were later recounted by Ovid in The Metamorphoses and are often divided into two thematic groups: love stories and punishment stories.

Love stories often included incest, the seduction or rape of a mortal woman by a god, resulting in heroic offspring. These stories generally suggest that relationships between gods and mortals are something to be avoided, even consensual relationships rarely having happy endings. the goddess lies with Anchises conceiving Aeneas.

The second type of stories (those of punishment) deals with the appropriation or invention of some important cultural artifact, such as when Prometheus steals fire from the gods, when he or Lycaon invents sacrifice, when Tantalus steals nectar and ambrosia from the table of Zeus and gives them to his own subjects, revealing to them the secrets of the gods, when Demeter teaches agriculture and the Mysteries to Triptolemus, or when Marsyas invents the aulos and engages in a musical contest with Apollo. Ian Morris considers the adventures of Prometheus "a point between the history of the gods and that of man."An anonymous papyrus fragment, dated to the 3rd century BC. C., vividly portrays Dionysus's punishment of the Thracian king Lycurgus, whose recognition of the new god came too late, resulting in horrific punishments that extended into the afterlife. The story of Dionysus' arrival to establish his cult in Thrace it was also the subject of an Aeschilian trilogy. In another tragedy, Euripides' Bacchantes, the king of Thebes, Pentheus, is punished by Dionysus for having been disrespectful to him and spied on the Maenads, his worshippers.

In another story, based on an ancient folkloric theme and reflecting a similar theme, Demeter was searching for her daughter Persephone after having taken the form of an old woman named Doso and received a hospitable welcome from Celeus, the king of Eleusis in Attica. As a gift to Celeus for his hospitality, Demeter planned to make her son Demophon immortal, but was unable to complete the ritual because his mother Metanira surprised her by putting the child in the fire and shrieked in fright, angering Demeter, who lamented that the stupid mortals did not understand the ritual.

The heroic age

The time in which the heroes lived is known as the heroic age. Genealogical and epic poetry created cycles of stories grouped around particular heroes or events and established the family relationships between the heroes of the different stories, thus organizing the stories into sequence. According to Ken Dowden "there is even a saga effect: we can follow the fates of some families in successive generations".

After the appearance of the heroic cult, gods and heroes constitute the sacred sphere and are invoked together in oaths, prayers addressed to them. In contrast to the age of the gods, during the heroic the relationship of heroes lacks a fixed and definitive form.; great gods are no longer born, but new gods can always arise from the army of the dead.

Another important difference between hero worship and god worship is that the hero becomes the center of local group identity. The monumental events of Heracles are considered the beginning of the age of heroes. Three great events are also ascribed to it: the Argonautical expedition and the Theban and Trojan wars.

Heracles, Perseo

Some researchers believe that behind the complicated mythology of Heracles there was probably a real man, perhaps a chieftain-vassal of the kingdom of Argos. Others suggest that the story of Heracles is an allegory of the sun's annual passage through the twelve constellations of the zodiac. Still others point to earlier myths from other cultures, showing the story of Heracles as a local adaptation of well-established heroic myths. Traditionally Heracles was the son of Zeus and Alcmene, granddaughter of Perseus.His fantastic solo exploits, with their many folk themes, provided much material for popular legends. He is portrayed as a sacrificer, mentioned as the founder of the altars and imagined as a ravenous eater, a role in which he appears in the comedies, while his unfortunate end provided much material for the tragedies: Heracles is considered by Thalia Papadopoulou "a play of great importance for the examination of other Euripidean dramas.In art and literature Heracles was depicted as an enormously strong man of moderate height, his characteristic weapon being the bow but also frequently the club. Painted vessels demonstrate Heracles' unrivaled popularity, with his fight with the lion appearing many hundreds of times.

Heracles also entered Etruscan and Roman mythology and worship, and the exclamation mehercule became as familiar to the Romans as Herakleis was to the Greeks. In Italy he was worshiped as a god of merchants and commerce, although others they also prayed to him for his characteristic gifts of good luck and rescue from danger.

Heracles achieved the highest social prestige through his position as the official ancestor of the Dorian kings. This probably served as legitimation for the Dorian migrations to the Peloponnese. Hilo, the eponymous hero of a Dorian tribe, became a Heraclidae, a name given to the many descendants of Heracles, including Macaria, Lamos, Manto, Bianor, Tlepolemus, and Telephus. These Heraclidae conquered the Peloponnesian kingdoms of Mycenae, Sparta, and Argos, claiming according to legend the right to rule over them due to their ancestry. His rise to power is often referred to as the "Dorian invasion." The Lydian and later the Macedonian kings, as rulers of the same rank, also became Heraclidae.

Other members of the first generation of heroes, such as Perseus, Deucalion, and Bellerophon, have many traits in common with Heracles. Like him, his exploits are solo, with fantastic and metaphorical overtones, since they faced and killed monsters like Chimera and Medusa. The latter had the ability to petrify her enemies with her gaze, so each god provided Perseus with a particular element to defeat her. Sending a hero to certain death is also a frequent theme in this early heroic tradition, as in the cases of Perseus and Bellerophon.

The Argonauts. Jason, Theseus, Minotaur

The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the Argonautics of Apollonius of Rhodes (epic poet, researcher and director of the Library of Alexandria) recounts the myth of the journey of Jason and the Argonauts to retrieve the Golden Fleece from the mythical land of Colchis. In the Argonautics Jason is pushed to search for him by King Pelias, who receives a prophecy about a man with a sandal who would be his nemesis. Jason loses a sandal in a river, reaching the court of Pelias and thus starting the epic. Nearly every member of the next generation of heroes, apart from Heracles, went with Jason on the Argo.to search for the golden fleece. This generation also included Theseus, who went to Crete to slay the Minotaur, the heroine Atalanta, and Meleager, who once had an epic cycle of his own that rivaled the Iliad and the Odyssey. Pindar, Apollonius, and Apollodorus endeavored to give complete lists of the Argonauts.

Although Apollonius wrote his poem in the 3rd century BC. C., the composition of the story of the Argonauts predates the Odyssey, which shows a familiarity with the exploits of Jason (the exploits of Odysseus may have been partially based on them). In ancient times the expedition was considered a fact historical, an incident in the opening of the Black Sea to Greek trade and colonization. It was also extremely popular, constituting a cycle to which many local legends were attached. In particular, the story of Medea captured the imagination of the tragic poets.

Theban cycle. Oedipus, Cadmus, Atreus

Between the Argo and the Trojan War there was a generation known primarily for its heinous crimes. These include the events of Atreus and Thyestes in Argos. Behind the myth of the house of Atreus (one of the two main heroic dynasties together with the house of Labdacus) is the problem of the return of power and the way of ascension to the throne. The twins Atreus and Thyestes with their descendants played the leading role in the tragedy of the devolution of power at Mycenae.

The Theban cycle deals with the events related especially to Cadmus, the founder of the city, and later with the events of Laius and Oedipus in Thebes, a series of stories that led to the final sack of the city at the hands of the seven against Thebes and the Epigones. (It is not known if they figured in the original epic.) As for Oedipus, ancient epic accounts seem to allow him to continue to rule in Thebes after the revelation that Jocasta was his mother, and then marry a second wife who she became the mother of his children, which is very different from the story we know from tragedies (for example, Sophocles' Oedipus Rex) and later mythological accounts.

The Trojan War. Achilles, Paris, Helen and the Amazons

Greek mythology culminates in the Trojan War, the struggle between the Greeks (Achaeans) and the Trojans, including its causes and consequences. In Homer's plays the main stories have already taken shape and substance, and the individual themes were elaborated later, especially in the Greek dramas. The Trojan War also attracted great interest in Roman culture due to the story of the Trojan hero Aeneas, whose journey from Troy led to the founding of the city that would one day become Rome, recorded by Virgil in the Aeneid (whose Book II contains the best known account of the sack of Troy). Finally there are two pseudo-chronicles written in Latin which passed under the names of Dictis Cretense and Dares Frigio.

The Trojan War cycle, a collection of epic poems, begins with the events that triggered the war: Eris and the golden apple 'for the fairest' (kallisti), the trial of Paris, the kidnapping of Helen, and the sacrifice of Ifigenia in Aulide. To rescue Helen, the Greeks organized a great expedition under the command of Menelaus's brother, Agamemnon, king of Argos or Mycenae, but the Trojans refused to release her from her. the iliad, which is set in the tenth year of the war, tells of Agamemnon's dispute with Achilles, who was the greatest Greek warrior, and the subsequent deaths in battle of Achilles' friend Patroclus and Priam's eldest son Hector. After his death, two exotic allies joined the Trojans: Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons, and Memnon, king of the Ethiopians and son of the dawn goddess Eos.Achilles killed them both, but Paris then managed to kill him with an arrow to the heel, the only part of his body vulnerable to human weapons. Before they could take Troy, the Greeks had to steal from the citadel the wooden image of Pallas Athena (the Palladium). Finally, with the help of Athena they built the Trojan horse. Despite the warnings of Priam's daughter Cassandra, the Trojans were convinced by Sinon, a Greek who had faked his desertion, to bring the horse inside the walls of Troy as an offering to Athena. The priest Laocoön, who tried to destroy the horse, was killed by sea serpents. At nightfall the Greek fleet returned and the warriors on horseback opened the gates of the city. In the complete plunder that followed, Priam and his remaining children were killed, passing the Trojan women to be slaves in various cities of Greece. The adventurous return journeys of the Greek leaders (including the wanderings of Odysseus and Aeneas, and the murder of Agamemnon) were chronicled in two epics, theReturns (Nostoi, now lost) and Homer's Odyssey. The Trojan cycle also includes the adventures of the sons of the Trojan generation (for example Orestes and Telemachus).

The Trojan cycle provided a variety of themes and became a major source of inspiration for ancient Greek artists (for example, the Parthenon metopes depicting the sack of Troy). This artistic preference for themes from the Trojan cycle indicates their importance to ancient Greek civilization. The same mythological cycle also inspired a number of later European literary works. For example, medieval European Trojan writers, unaware of Homer's work, found in the Trojan legend a rich source of heroic and romantic stories and a suitable framework into which to fit their own courtly and chivalric ideals. Twelfth-century authors, such as Benoît de Sainte-Maure (Poem of Troy, 1154-60) and José Iscano (De bello troiano, 1183) describe the war while rewriting the standard version they found in Dictis and Dares, thus following Horace's advice and Virgil's example: rewrite a Trojan poem instead of telling something entirely new.

Greek and Roman conceptions of myths

Greek mythology has changed over time to accommodate the evolution of its own culture, of which the mythology is an index, both expressly and in its implicit assumptions. In the surviving literary forms of Greek mythology, as it stands at the end of progressive changes, it is inherently political.

Mythology was at the heart of everyday life in ancient Greece. The Greeks considered mythology a part of their history. They used myths to explain natural phenomena, cultural differences, enmities, and traditional friendships. It was a source of pride to be able to trace one's leaders back to a mythological hero or god. Few doubted the factual basis for the account of the Trojan War in the Iliad and the Odyssey. According to Victor Davis Hanson and John Heath, the profound knowledge of the Homeric epic was considered by the Greeks to be the basis of their acculturation. Homer was the "education of Greece" (Ἑλλάδος παίδευσις) and his poetry "the Book".

Philosophy and mythology

After the rise of philosophy, history, prose and rationalism at the end of the 5th century BC. The fate of the myths became uncertain, and mythological genealogies gave way to a conception of history that attempted to exclude the supernatural (such as the Thucydidian story). While poets and playwrights were reworking the myths, historians and philosophers Greeks were beginning to criticize them.

A few radical philosophers like Xenophanes of Colophon were already beginning to label the stories of the poets as blasphemous lies in the 6th century BC. C.: Xenophanes had complained that Homer and Hesiod attributed to the gods "everything that is shameful and disgraceful among men: theft, the commission of adultery, and mutual deceit". This line of thought found further expression. drama in The Republic and the Laws of Plato, who created his own allegorical myths (such as that of Er in The Republic) attacking traditional accounts of divine deceit, theft, and adultery as immoral and opposing their central role in literature.Plato's critique was the first serious challenge to the Homeric mythological tradition, referring to the myths as "old women's chatter". theologians were only concerned with what seemed plausible to them and had no respect for us... But writers who boast in the mythological style are not worth taking seriously; As for those who proceed to prove their claims we must re-examine them.

However, not even Plato managed to wean his society from the influence of myths: his own characterization of Socrates is based on the traditional Homeric and tragic patterns used by the philosopher to praise his master's righteous life:Perhaps some of you, inside, are reproaching me: "Aren't you ashamed, Socrates, to see yourself involved in these troubles because of your occupation, which is taking you to the point of endangering your own life?"To these he would reply, and very convinced by the way: «You are completely wrong, my friend; a man with a minimum of courage should not be worried about those possible risks of death, but he should only consider the honesty of his actions, if they are the result of a just or unjust man. Well, according to your reasoning, the lives of those demigods who died in Troy would have been unworthy, especially the son of the goddess Tethys, for whom death counted so little, if one had to live shamefully; he despised danger so much that, in his ardent desire to kill Hector to avenge the death of his friend Patroclus, he ignored his mother, the goddess, when she said to him: "My son, if you avenge the death of your companion Patroclus and you kill Hector, you yourself will die, for your fate is linked to his.” Unlike, he had little time for death and danger and, fearing living cowardly much more than dying to avenge a friend, he replied: "I prefer to die right here, after having punished the murderer, than to remain alive, the object of ridicule and contempt, being useless load of the earth, dragging me along with the concave ships”. Was he worried, then, about dangers and death? »

Plato,

Apology 28b–d.

Hanson and Heath estimate that Plato's rejection of the Homeric tradition was not received favorably by the base of Greek civilization. The old myths were kept alive in local cults and continued to influence poetry and form the main subject of painting and painting. the sculpture.

More sportingly, the writer of tragedies of the V century a. C., Euripides, frequently played with the old traditions, mocking them and instilling notes of doubt through the voice of his characters, although the themes of his works were taken, without exception, from the myths. Many of these works were written in response to a predecessor's version of the same or similar myth. Euripides primarily contests the myths about the gods, and begins his criticism of them with an objection similar to one previously expressed by Xenocrates: the gods, as traditionally depicted, are too callously anthropomorphic.

Hellenistic and Roman rationalism

During the Hellenistic period, mythology acquired the prestige of elitist knowledge that marked its possessors as belonging to a certain class. At the same time, the skeptical turn of the classical age became even more pronounced. The Greek mythographer Euhemerus founded the tradition of seeking a real historical basis for mythological beings and events. Although his original work (Sacred Scriptures) has been lost, much is known about her from what Diodorus Siculus and Lactantius recorded.

Rationalizing hermeneutics of mythology became even more popular under the Roman Empire, thanks to the physicalist theories of Stoic and Epicurean philosophy. The Stoics presented explanations of the gods and heroes as physical phenomena, while the Euhemerists rationalized them as historical figures. At the same time, the Stoics and Neoplatonists promoted the moral meanings of the mythological tradition, often based on Greek etymologies. Through his Epicurean message, Lucretius had sought to expel superstitious fears from the minds of his fellow citizens. Livy was also skeptical of the mythological tradition and claimed that he did not attempt to prosecute such legends (fabulae).The challenge for Romans with a strong apologetic sense of religious tradition was to defend that tradition while conceding that it was often a breeding ground for superstition. The antiquarian Varrón, who considered religion a human institution of great importance for the preservation of good in society, dedicated rigorous studies to the origins of religious cults. In his Antiquitates Rerum Divinarum (which is not extant, although Augustine 's City of God indicates his general approach) Varro argues that while the superstitious man fears the gods, the truly religious person reveres them as fathers. In his work he distinguished three types of gods:

- Gods of nature: personifications of phenomena such as rain and fire.

- Gods of poets: invented by unscrupulous bards to incite the passions.

- Gods of the city: invented by wise legislators to reassure and enlighten the people.

The Roman scholar Gaius Aurelius Cotta ridiculed both literal and allegorical acceptance of myths, stating flatly that they had no place in philosophy. their institutions. It is difficult to know how far down the social scale this rationalism extended. Cicero asserts that no one (not even old women and children) is foolish enough to believe in the terrors of Hades or the existence of Scylla, centaurs, or other creatures. but otherwise the speaker complains the rest of the time about the superstitious and credulous character of the people. De natura deorum is Cicero's most exhaustive summary of this line of thought.

Syncretic trends

In Ancient Rome a new Roman mythology appeared thanks to the syncretization of numerous Greek gods and those of other nations. This was because the Romans had little mythology of their own and the heritage of the Greek mythological tradition caused the major Roman gods to adopt traits from their Greek counterparts. The gods Zeus and Jupiter are an example of this mythological overlap. In addition to the combination of two mythological traditions, the relationship of the Romans with Eastern religions led to further syncretizations.For example, the cult of the Sun was introduced to Rome after Aurelian's successful campaigns in Syria. The Asiatic divinities Mithras (i.e. the Sun) and Baal were combined with Apollo and Helios into a single Sol Invictus, with conglomerate rites and composite attributes. Apollo could increasingly be identified in religion with Helios or even Dionysus, but the texts recapitulating their myths seldom reflected these developments. Traditional literary mythology was increasingly dissociated from actual religious practices.

The collection of Orphic hymns and the Saturnalia of Macrobius, preserved from the second century, are also influenced by rationalist theories and syncretic tendencies. The Orphic hymns are a set of pre-classical poetic compositions, attributed to Orpheus, himself the subject of a renowned myth. In reality, these poems were probably composed by several different poets, and contain a rich body of clues about prehistoric European mythology. The Saturnalia 's stated intention is to convey the Hellenic culture that he had gained from his reading, even though much of his treatment of the gods is contaminated by Egyptian and North African mythology and theology (also affecting Virgil's interpretation). In theSaturnalia mythographic comments influenced by the Euhemerists, Stoics and Neoplatonists reappear.

Modern interpretations

The genesis of the modern understanding of Greek mythology is considered by some researchers to be a double reaction at the end of the 18th century against «the traditional attitude of Christian animosity», in which the Christian reinterpretation of the myths as a «lie» or fable it had been preserved. In Germany, around 1795, there was a growing interest in Homer and Greek mythology. At Göttingen Johann Matthias Gesner began to revive Greek studies, while his successor, Christian Gottlob Heyne, worked with Johann Joachim Winckelmann and laid the foundation for mythological research both in Germany and elsewhere.

Comparative and psychoanalytic approaches

The development of comparative philology in the nineteenth century, together with the ethnological discoveries of the twentieth century, founded the science of mythology. Since Romanticism all the study of myths has been comparative. Wilhelm Mannhardt, Sir James Frazer and Stith Thompson used the comparative approach to collect and classify the subjects of folklore and mythology. In 1871 Edward Burnett Tylor published his Primitive Culture, in which he applied the comparative method and attempted to explain the origin and evolution of religion.Tylor's approach to bringing together the cultural, ritual, and mythical material of widely separated cultures influenced both Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell. Max Müller applied the new science of comparative mythology to the study of myths, in which he detected the distorted remnants of Aryan nature worship. Bronisław Malinowski emphasized the ways in which myths fulfilled common social functions. Claude Lévi-Strauss and other structuralists have compared the formal relationships and patterns in myths from around the world.

Sigmund Freud presented a transhistorical and biological conception of man and a vision of myth as an expression of repressed ideas. The interpretation of dreams is the basis of the Freudian interpretation of myths and his concept of dreams recognizes the importance of contextual relationships for the interpretation of any individual element of a dream. This suggestion would find an important point of rapprochement between the structuralist and psychoanalyst views of myths in Freud's thought. Carl Jung extended the transhistorical and psychological approach with his theory of the "collective unconscious" and archetypes ("archaic" inherited patterns), often codified in the myths, that arise from it.According to Jung, "the structural elements that form myths must be presented in the unconscious psyche." Comparing Jung's methodology with Joseph Campbell's theory, Robert A. Segal concludes that "to interpret a myth Campbell simply identifies the archetypes in it. An interpretation of the Odyssey, for example, would show how Odysseus' life fits into a heroic pattern. Jung, by contrast, regards the identification of archetypes as merely the first step in the interpretation of a myth." Károly Kerényi, one of the founders of modern studies of Greek mythology, abandoned his earlier views on myths for apply Jung's archetypal theories to Greek myths,as the reinterpretation of Achilles and Patroclus.

Theories about its origins

There are several modern theories about the origins of Greek mythology. According to the scriptural theory, all mythological legends come from accounts in the sacred texts, although the actual events have been modified. According to the historical theory, all the people mentioned in mythology were once real human beings and the legends about them are additions. of later times. Thus, the story of Aeolus is supposed to have arisen from the fact that he was the ruler of some islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea. The allegorical theory assumes that all ancient myths were allegorical and symbolic. While the physical theoryadheres to the idea that the elements of air, fire and water were originally objects of religious worship, so that the main deities were personifications of these powers of nature. Max Müller tried to understand a Proto-Indo-European religious form by determining its manifestation " original". In 1891, he stated that "the most important discovery that has been made in the nineteenth century regarding the ancient history of mankind [...] was this simple equation: Dyeus-pitar Sanskrit=Zeus Greek=Jupiter Latin=Tyr Norse", although the equivalent of Zeus in the Viking religion is Thor or Odin, it is usually syncretized.In other cases, close parallels in character and function suggest a common heritage, although the absence of linguistic evidence makes it difficult to prove, as in the comparison between Uranus and the Sanskrit Varuna or the Moirai and the Norns.

On the other hand, archeology and mythography have revealed that the Greeks were inspired by some civilizations of Asia Minor and the Near East. Adonis seems to be the Greek equivalent—more clearly in the cults than in the myths—of a Near Eastern 'dying god'. Cybele has its roots in Anatolian culture while much of Aphrodite's iconography stems from Semitic goddesses. There are also possible parallels between the older divine generations (Chaos and her children) and Tiamat in the Enûma Elish. According to Meyer Reinhold, "Near Eastern theogonic concepts, including divine succession through violence and generational conflicts over power, found their way... into Greek mythology'.In addition to Indo-European and Near Eastern origins, some researchers have speculated on Greek mythology's debts to pre-Hellenic societies: Crete, Mycenae, Pylos, Thebes, and Orchomenus. Historians of religion were fascinated by various configurations of myths apparently ancient related to Crete (the god as a bull, Zeus and Europa, Pasiphae lying with the bull and giving birth to the Minotaur, etc.). Professor Martin P. Nilsson concluded that all the great classical Greek myths were tied to the Mycenaean centers and anchored in prehistoric times. However, according to Burkert the iconography of the Cretan palace period has given virtually no confirmation to these theories..

Greek mythology in Renaissance art

When the Roman Empire issued the Edict of Thessalonica in the 4th century AD. C. as a compulsory adoption of Christianity as the official religion, the popularity of Greek mythology was definitively curbed: the original cults of the peoples that had been conquered by Rome were prohibited. This gradually returned, a thousand years later with the rediscovery of classical antiquity in the Renaissance, in the fifteenth century, under suspicion by the clergy. There then, the poetry of Ovid became a major influence on the imagination of poets, playwrights, musicians, and artists. From the early years of the Renaissance, artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael portrayed the pagan themes of Greek mythology (as well as Christianity),where poets such as Petrarch, Boccaccio and Dante stood out in Italy.

In Northern Europe, Greek mythology reached importance in the visual arts, such as Rubens, Ferdinand Bol, Rembrandt, Bertel Thorvaldsen, Johan Tobias Sergel, Gyger Hinterglasbild. Greek mythology caught the English imagination of Chaucer and John Milton and continued through Shakespeare to Robert Bridges in the 20th century. Racine in France and Goethe in Germany revived Greek drama, reinterpreting ancient myths. Although a reaction against Greek myths spread throughout Europe during the Enlightenment, they remained an important source of material for playwrights, including playwrights. from the librettos of many operas by Händel and Mozart.By the end of the 18th century, Romanticism saw a surge of enthusiasm for all things Greek, including mythology. In Britain, new translations of Greek tragedies and the works of Homer inspired contemporary poets (such as Alfred Tennyson, Keats, Byron, and Shelley) and painters (such as Lord Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema). Gluck, Richard Strauss, Offenbach and many others brought Greek mythological themes to music. Nineteenth-century American authors such as Thomas Bulfinch and Nathaniel Hawthorne argued that the study of classical myths was essential to an understanding of English and American literature.In more recent times, classical themes have been reinterpreted by playwrights Jean Anouilh, Jean Cocteau, and Jean Giraudoux in France, Eugene O'Neill in the United States, and TS Eliot in Britain, and by novelists such as James Joyce and André Gide.

Contenido relacionado

Neoptolemus

Mu (lost continent)

Erinyes