Greek language

The Greek (in ancient Greek: Ἑλληνική ɣλῶσσα or Ἑλληνική ɣλῶττα; Ελληνική γλώσ>sαpan title="sαpan Representation in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA or IPA)" class="IPA">[eliniˈci ˈɣlosa] or Ελληνικά [eliniˈka] in modern Greek; in Latin: Lingua Graeca) is a language native to Greece, which belongs to the Greek branch of the Indo-European languages. It is the Indo-European language with the longest documented history, since it has more than 3,400 years of written evidence. The writing system that it has used for most of its history and up to the present day is the Greek alphabet. Previously, he used other systems, such as Linear B or the Cypriot syllabary. The Greek alphabet derives from the Phoenician, and in turn gave rise to the Latin, Cyrillic and Coptic alphabets, among others.

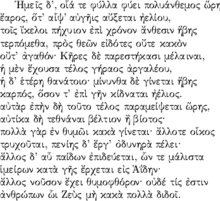

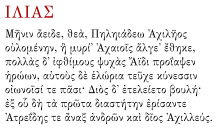

Greek occupies an important place in the history of Europe, the so-called Western civilization and Christianity. The canon of ancient Greek literature includes works of monumental importance and influence for the future Western canon, such as the epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey. Many of the founding texts of Western philosophy, such as the Platonic dialogues or the works of Aristotle, were also written in Greek. The New Testament of the Bible was written in koine Greek, the language in which the liturgy of various Christian denominations (especially the Orthodox Church and the Byzantine rite of the Catholic Church) continues to be celebrated. Together with the Latin texts and the traditions of the Roman world, profoundly influenced by ancient Greek society, it forms the discipline of classical studies.

Modern Greek, as it is known today, derives from ancient Greek through medieval or Byzantine Greek and is the official language of Greece and Cyprus, as well as being one of the official languages of the European Union. The current linguistic standard was developed after the Greek War of Independence (1821-1831) and is based on the popular language (the dimotiki), although with considerable influence from the archaic learned language developed over the years. from the 19th and 20th centuries (the katharévousa), which was the official norm until 1976. Minorities of Greek speakers exist in southern Albania and southern Italy, where Griko is spoken (or Greco-Calabrian) and Grecanic (or Greco-Salentine). Around the Black Sea there are still minorities of speakers of the Pontic dialect. In addition, since the end of the xix there have been Greek-speaking communities descended from emigrants in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Chile, Venezuela and Mexico.

Historical, social and cultural aspects

History

The Greek languages or dialects together constitute the Hellenic branch or subfamily of the Indo-European family. With a written record of some 3,400 years, Greek is one of the languages (properly a group of languages) whose historical development can be followed over a longer period, surpassed only by those written in the Chinese, Egyptian, and Hittite languages. The Greek language can be divided into at least seven stages:

- Origins: the prehistory of the Greek language has advanced mainly due to the theories of the indo-European developed since the mid-centuryxix. The Greek, like the languages of the Indorian and Armenian group, derives linguistically from the dialects spoken by peoples that probably moved to the mid-iv millennia. C. from the northern steppes of the Black Sea (or Ponto Euxino) to the lower valley of the Danube River. From this region the protohelénic speakers moved southward, towards the Balkan peninsula.

- Archaic Greek: it is estimated that around the ii millennium a. C. came to the Peloponnese and some islands of the Aegean Sea the first wave of Greek dialect speakers. They have been identified as the φχάιοι (akháioiHomer and the ahhiyawa from the Hittite sources. The talk of the aqueos seems to be the basis of the later Ionian-Attic dialects. The prehelmenic inhabitants of the peninsula (pelasgos) were displaced or absorbed by the Greek speakers, although they left a patent substratum above all in toponymy. It also left a certain linguistic substrate the non-indo-European language of the minoids, which has been preserved in linear A, although it has not yet been deciphered. The aqueos gave rise to micenic civilization, from which inscriptions have been preserved in linear writing B, derived from linear writing A minoica. The language of these inscriptions in bustrófedon is clearly a form of Greek, quite uniform throughout its entire domain, which is known as a micenic Greek. In the xith century B.C., micenic civilization came to an end because of the invasions of another Greek group, speakers of doric dialects. Linear B ceased to be used and began a "dark time" without direct written testimonies. Between the centuries xi and I saw a. C. Homerical poems were written, based on an earlier oral tradition dating back to the micenic era. These poems were written in a mixture of eolite dialects and Ionic dialects and an alphabet based on a Phoenician model, which would eventually result in the classical Greek alphabet.

- Ancient Greek ()ρχαία)λληνικх): the so-called classic Greek is a standardized literary form based on the talk of Athens, an attic dialect with a strong Ionic influence. In Antiquity there were always other Greek variants commonly called dialects for more than they should really be conceived as Greek languages other than the Greek attic, although closely related to it. The Greek who is often studied as a model is the attic dialect, as in it they wrote most of the great Greek authors. They wrote, among others, the philosopher Aristotle, the historian Polibio and the moralist Plutarco. The different ancient dialects were five:

- Griego panfilio (σαμφυλιακς). It was an ancient Greek dialect, isolated and undocumented, spoken in Panfilia, on the south coast of Asia Minor. Also considered semi-bárbaro by the Greeks of the motherland and effectively contaminated by the influences extracted from the non-Greek language.

- Greek Northwest and Draric (Δωρικ διάλεκτος). Speaking in the northwest of Greece, mainly much of the Epiro, Molosia and Macedonia, as well as the peninsula of the Peloponnese, the southern part of the coast of Asia Minor, the islands of Crete and Rhodes and much of the Magna Greece.

- Elic (Axiολικος). Speaking on the north side of the coast of Asia Minor, on the island of Lesbos, Tesalia and Beocia.

- Arcadio-chipriota (Yρκαδοκυπριακ διάλεκτος): Speaking in Arcadia and the island of Cyprus. It was replaced by the common language (koiné) to later give way to the present Greek-chipriota.

- Ionical-attic. Dialectal group consisting of:

- Jónico ()ωκ) διάλεκτος). Speaking in Eubea, on the Aegean Islands and in Jonia (the coastal region of Anatolia that includes the cities of Esmirna, Ephesus and Mileto. This dialect is the basis of the language of Homer, Hesiod and Herodotus.

- Dialecto homérico (OMμηρικά ελλικά). Epic language, which is based primarily on the Ionian dialect, with characteristics taken from the eolio dialect. Alterna archaic and classic forms and was employed by Homer in the Iliad and the Odyssey.

- Penthouse ().τικ).).λληνικх). Speaking in Athens and the peninsula of the Atica.

- Jónico ()ωκ) διάλεκτος). Speaking in Eubea, on the Aegean Islands and in Jonia (the coastal region of Anatolia that includes the cities of Esmirna, Ephesus and Mileto. This dialect is the basis of the language of Homer, Hesiod and Herodotus.

- Hellenistic Greek (Κοιν): אλίσα): Given the commercial and cultural importance of Athens, especially since the Hellenistic period (323-31 BC), it was the dialect that served as a model for the later common language or language. koinè glôssa, He became a literary language throughout Greece and spread with the conquests of Alexander the Great to the East. Although the attic dialect lost its original purity, it evolved and enriched with the contributions of the different spoken languages the territories that formed the vast empire of Alexander the Great, from Rome to some enclaves in India, passing through Egypt. It is the main dialect of the biblical Greek, both of the Old Testament translations and the writing of the New, with an important amount of lexicon loans of semitic languages, such as Aramaic and Hebrew. The koiné became the official language of the Roman Empire along with the Latin and, after the fall of the western part of the empire, remained the official language of the Roman Empire of the East or Byzantine.

- Aticism ()τικισμός): It was a rhetorical and literary movement, which began in the post-classic era, during the first quarter of the 1st century BC. Literally means follow-up to the attics. Euclides and other authors of the time of the Greek koiné tried to return to the purity of the modern attic. It was characterized by the correctness, simplicity, delicacy and elegance of the Athenian writers and speakers of classical Greece, trying to imitate the classic attic dialect.

- Medieval Greek (MMεσαιωνικς Ελλικς): Although the official language of the Byzantine Empire (395-1453) was the koiné (κοιν dialogue), it continued to evolve to give rise to what is known as medieval or Byzantine Greek. As was the case in the western part of the empire with the Latin, a situation of diglosia was created in which the written language remained the ancient koiné, while the oral language was accusing more and more differentiated phonetic, lexicon and grammatical traits.

- Modern Greek (non-severalα Ελληνικς): simple form derived from the common Greek or koiné. It is conventionally adopted the taking of Constantinople by the Ottomans (1453) as the date of appearance of the modern Greek, although its main features already appeared in the medieval Greek. With the loss of officiality, the popular language became even more distasteful of the cultured language, which accentuated the pre-existing diglosia. In 1831, with the emergence of the nation State in the Kingdom of Greece, the Greek is established as an official language. However, this fact was marked by the Greek linguistic issue, a debate around the adoption as an official language of an arkizing variety inspired by the koiné (καθαρεςσα) or the δ Cristianμοτικς (dimotikí), the popular language. This dispute was resolved in 1976 with the official adoption of the demotic Greek by the hellenic government; however, the standard modern language is considerably influenced by the kathévousa. It is a more analytical and synthetic language and its grammar differs significantly from the classic Greek, so much so that it is not so easily understandable for a contemporary Greek. Mention apart deserves the dialect spoken in Cyprus, the Greek Cypriot, whose pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary, differ significantly from the standard demotic Greek spoken in Greece, so much that a Greek speaker might find it difficult to understand a Cypriot.

Historical continuity

It is common to emphasize the historical continuity of the various stages of the Greek language. Although Greek has undergone morphological and phonological changes comparable to those of other languages, there has been no time in its history since classical antiquity when its cultural, literary, or orthographic tradition has been interrupted to the point that it can be easily determine the emergence of a new language. Even today Greek speakers tend to regard ancient Greek literary works more as part of their language than a foreign language. Furthermore, it is often claimed that the historical changes have been relatively small compared to other languages. According to Margaret Alexíou, "Homeric Greek is probably closer to Demotic than xii English is to current oral English". The perception of historical continuity is also reinforced by the fact that Greek has very little divided into several daughter languages, as has happened with Latin. Along with Standard Modern Greek (in both its katharévousa and demotic registers), the other varieties derived from Greek are Pontic Greek, Eastern Peloponnesian Tsakonian (today highly threatened), Griko (or Greco-Salentine) and Grecanic (or Greco-Calabrian).) from southern Italy.

Geographic distribution

Greek is the official and majority language of Greece and Cyprus. As a minority language it has been present for more than two thousand years in southern Albania and southern Italy. In Italy it is found in southern Apulia (in Salentina Greece), where Griko is spoken, and also in southern Calabria (in Bovesia), where Grecanic is spoken. Likewise, there have been Greek minorities for more than two thousand years in territories today occupied by Turkey, mainly in present-day Istanbul, Izmir, other areas of Eastern Thrace and the Anatolian coasts of the Aegean Sea and the Sea of Marmara. Similarly, the small Greek-speaking communities in some coastal sites in the Republic of Georgia (including Pitiys on the coast of Abkhazia), in Ukraine (particularly on the Crimean peninsula and in the southern part of the historical region of Zaporozhia) are very old.), and off the coasts of Bulgaria and Romania.

Since the late 19th century there have been some Greek-speaking communities descended from emigrants in France, Germany, England, Australia, the United States, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, Venezuela and Mexico. It is, therefore, a language with a large area of dispersion and great historical and philological importance in world culture, since the most important European languages today have thousands of words in common use with Greek etymons. All in all, it is considered that Greek was usually spoken by about sixteen million people in 2006.

Linguistic description

Phylogenetic classification

Modern Greek, Greek Cypriot, Greco-Italian dialects, Cappadocian, Pontic, and Tsakonian are now the sole survivors of the Greek branch of the Indo-European languages. Other important but already disappeared languages of this branch were Mycenaean Greek, Attic Greek and Hellenistic Greek, extended thanks to the conquests of Alexander the Great and from which all current varieties derive, with the exception of Tsakonic.

Phonology and writing

Phonology

Throughout its history, the syllabic structure of Greek has changed little: Greek displays a mixed syllabic structure, allowing complex syllabic attacks but restricted codas. It has only oral vowels and a fairly stable series of consonantal contrasts. The main phonological changes took place during the Hellenistic period and included at least four changes:

- The shift from the tonal accent to the prosodic accent.

- The simplification of the vocal and diptongo system, with the loss of the distinction of vocálica length, the monoptongation of the majority of diptongos and the transformation of a good number of vowels in /i/ (iotacism), which resulted in only five vocálic phenomas: /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/ and /u/.

- The evolution of deaf occluent consonants /ph/ and /th/ in the deaf cold /f/ and /θ/ respectively. Perhaps later a similar evolution took place /kh/ a /x/. However, these phenological changes were never reflected in the spelling: both phenomas and others have been written with φ, θ and χ.

- The possible evolution of sound occluent consonants /b/, /d/ and /// to its corresponding sound frictions /β/ (after /v/), /ð/ and /.

Writing

The alphabet used by modern Greek is practically the same as that of classical Greek; only the sound of some letters has been modified. Instead, some dialectal or archaic letters used around the vii and vi a. C. such as the double gamma or digamma (approximate phonetic value [w]), the qoppa ([k]), the sampi ([ss], [ts]) and the san ([s]). A way of writing the letter sigma used in Alexandrian Koine and Byzantine Greek whose grapheme was C, also fell into disuse, a letter that has remained as a legacy in the Cyrillic alphabet with the phonetic value of s.

| letter | Name in Spanish | classical pronunciation | Current pronunciation |

| α | alpha | [a], [a devoted] | [a]; αι [e]; αυ [av], [af] |

| VAL β | beta | [b] | [v] |

| ↓ | gamma | [g]; ∞ [ng] | [o], [o], [u]; [;] ante [e], [i]; [ng]; [g] at the beginning of the word, [σ de] in the middle |

| Δ δ | delta | [d] | [δ] |

| Ε ε | Epsilon | [e]; ει [e development] | [e]; ει [i]; ευ [ev], [ef] |

| φ ה | dseta | [zd], [dz], [z] | [z] |

| H λ | eta | [chuckles]▪] | [i]; . [i]; θ [iv], [if] |

| θ | zeta | [chuckles]th] | [θ] |

| ONE | iota | [i] [i devoted] | [i], [j] |

| K κ | kappa | [k] | [k], [c] |

| λ | lambda | [l] | [l], []] |

| M μ | my | [m] | [m], [m;]; μπ [b] at the beginning of the word, [mb] in the middle |

| No. | and | [n] | [n], [;]; ντ [d] at the beginning of the word, [nd] in the middle |

| ・ | xi | [ks] | [ks] |

| WOMAN: | omicron | [o]; ONE [;i]; ♪ [u], [u devoted], [o devoted] | [o]; ONE [i]; ♪ [u] |

| π | piss | [p] | [p] |

| ro | [chuckles]♥], [r]; [ fliph], [rh] | [chuckles]♥], [r] | |

| σ, ς | sigma | [s] | [s], [ь]; |

| Τ Δ | tau | [t] | [t]; Δ [dz]; τσ [ts] [ts] |

| YES | ípsilon | [u], [u destined] 한 [y], [y devoted]; ## [and knock] | [i]; ## [i] |

| φ | fi | [chuckles]ph] | [f] |

| χ | ji | [chuckles]kh], γχ [GUEkh] | [x] ante [a], [o], [u]; [ç] ante [i, e]; γχ [^] or [. |

| ψ | psi | [ps] | [ps] |

| Ω Δ | omega | [chuckles]ː] | [o] |

Morphology

At all its stages, Greek morphology shows a great variety of derivational affixations, a limited but productive system of composition, and a rich inflectional system. While the morphological categories have remained stable over time, the morphological changes have been notable, especially in the nominal and verbal systems. The main change in nominal morphology was the loss of the dative, whose functions were replaced mainly by the genitive. In verbal morphology, the main change was the loss of infinitives, which led to a consequent increase in new periphrastic forms.

Nominal morphology

Pronouns show marks of person (first, second, and third), number (singular, dual, and plural in ancient Greek; singular and plural in later stages), and gender (masculine, feminine, and neuter), as well as declension with cases (from six cases in the archaic forms to four in modern Greek). Nouns, articles, and adjectives mark all of these distinctions except person. Both attributive and predicative adjectives agree with the noun.

Verb morphology

The inflectional categories of the Greek verb have remained relatively stable throughout Greek history, although with significant changes in terms of the number of distinctions in each category and their morphological expression. Greek verbs have synthetic inflectional forms for:

| person | Ancient: first, second and third |

| Modern: first, second and third; second person | |

| Number | Ancient: singular, dual and plural |

| Modern: singular and plural | |

| time | Ancient: present, past, future |

| Modern: present and not present (the future is peripheral) | |

| appearance | Ancient: imperfect, perfectivo (traditionally aoristo), perfect |

| Modern: perfective and imperfective | |

| mode | Ancient: indicative, subjunctive, imperative, optional |

| Modern: indicative, subjunctive and imperative | |

| voice | Ancient: active, medium and passive |

| Modern: active and medium-passive |

Syntax

Many aspects of Greek syntax have remained constant: verbs only agree on the subject, the use of the remaining cases is almost intact (nominative for subjects and attributes, accusative for direct objects and after almost all prepositions, genitive for possession), the article precedes the noun, appositives are generally prepositional, relative clauses follow the noun they modify, relative pronouns are positioned at the beginning of their proposition, etc. However, the morphological changes also had their equivalents in syntax, and there are therefore significant differences between ancient and modern syntax. Ancient Greek very frequently used participle and infinitive constructions, while modern Greek lacks an infinitive and instead uses a wide variety of periphrastic constructions, using participles more restrictedly. The loss of the dative led to an increase in indirect objects marked by a preposition or with a genitive. The old word order tended to be SOV, while the modern is SVO or VSO.

Lexicon

Most of the Ancient Greek lexicon is inherited, but includes a number of borrowings from the languages of the populations that inhabited Greece before the arrival of the Proto-Greeks. Words of non-Indo-European origin have been identified as early as Mycenaean times, with place names standing out in number. Most of the modern Greek lexicon, on the other hand, has been directly inherited from ancient Greek, albeit with semantic changes in quite a few cases. Borrowings have been taken mainly from Latin, Venetian, and Turkish. Generally, borrowings taken before xx adopted the Greek declension, while later borrowings, especially those borrowed from French and English, they are indeclinable.

Contenido relacionado

Glyph

Catalan language

Historical eruptions of Tenerife