Golden age

The Spanish Golden Age is a historical period in which Castilian thought, art and letters flourished, and which coincided with the political and military rise of the Spanish Empire of the House of Trastámara and of the House of Austria. The Golden Age is not framed in specific dates, although it is generally considered that it lasted more than a century, between 1492, the year of the end of the Reconquest, the Discovery of America, and the publication of the Castilian Grammar by Antonio de Nebrija, and the year 1659, in which Spain and France signed the Treaty of the Pyrenees. The last great writer of the Golden Age, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, died in 1681, a year also considered the end of the Spanish Golden Age.

Name

It is Hesiod who speaks for the first time of the five epochs or Ages of man in Works and days: golden, silver, bronze, heroic and the current iron age, each more and more degraded. The term, then, Golden Age, was conceived in the likeness of this myth to celebrate a time of excellence in all orders. According to Juan Manuel Rozas, the denomination arose in Alonso Verdugo's admission speech in the RAE (1736), and Ignacio de Luzán took it for the third chapter of his widely publicized Poetics (1737); What's more, the following year the scholar Gregorio Mayáns y Siscar used it in the dedication of his Life of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1738), with which it was already authorized for use by the literary critic eighteenth-century Luis José Velázquez, Marqués de Valdeflores (1722-1772) in 1754 in his work Origenes de la poesía castellana, although to refer exclusively to the period between the Catholic Monarchs and the death of Felipe III, that is, the late fifteenth century, the entire XVI century and the seventeenth no later than 1621. They were thus excluded Pedro Calderón de la Barca and other important authors. Subsequently, the definition was expanded, encompassing the entire classical period or the heyday of Spanish culture, essentially the Renaissance of the XVI century and the Baroque of the XVII century. For historiography and modern theorists, then, and sticking to specific dates of key events, the Golden Age spans from the publication of Nebrija's Gramática castellana in 1492 until Calderón's death in 1681.

Currently, the concept of the Golden Age tends to be defined comprehensively simply as relative to the cultural process of art, literature and thought that logically cannot be dismembered or explained in a biased way, as has been claimed too many times. As a basic postulate, a statute for the Golden Age without the School of Salamanca is not conceivable.

Introduction

At the end of the 18th century, the expression «Golden Age» had already become popular (created in 1736, and which soon caught on) which aroused the admiration of Don Quixote in his famous speech on the Golden Age. But the extension of its limits fell to Casiano Pellicer, who in 1804 extended it to Calderón and his school in his Historical treatise on the origin and progress of comedy... . In the 19th century, the American Hispanist George Ticknor finished consecrating it in his History of Spanish literature; However, it was not necessary to include Luis de Góngora and his followers, which was taken care of at the beginning of the XX century by Alfonso Reyes and the Generation of 27. Helmut Hatzfeld divided, on the other hand, the literary Golden Age into four aesthetic periods: Renaissance (1530-1580), Mannerism (1570-1600), Baroque (1600-1630) and Baroque (1630-1670). José Antonio Maravall interprets the baroque as "a historical concept" and delimits it between 1600 and 1670-80. Ángel del Río and Fernando Rodríguez de la Flor, for their part, estimate that the Baroque would cover the hundred years between 1580 and 1680.

With their dynastic union, the Catholic Monarchs had outlined a politically strong State, consolidated later, whose successes were envied by some contemporary intellectuals, such as Nicholas Machiavelli. The Jews who did not become Christianized were expelled in 1492 and dispersed, founding Hispanic colonies throughout Europe, Asia and North Africa, where they continued to cultivate their language and write literature in Spanish, in such a way that they also produced notable figures such as José Penso de la Vega., Miguel de Silveira, Jacob Uziel, Miguel de Barrios, Antonio Enríquez Gómez, Juan de Prado, Isaac Cardoso, Abraham Zacuto, Isaac Orobio de Castro, Juan Pinto Delgado, Rodrigo Méndez Silva or Manuel de Pina, among others.

In January 1492, Castilla conquered Granada, thus ending the Muslim political period on the peninsula, although a Moorish minority inhabited it more or less tolerated until the time of Philip III. In addition, in October Columbus arrives in America and the warrior desire cultivated during the medieval wars of the Reconquista will be projected on the new lands. Conquistadors, missionaries and adventurers are the protagonists, with their risky expeditions and their thirst for gold and evangelization, "the most extraordinary epic in human history" according to the historian Pierre Vilar. However, and about Around the middle of the XVI century, erasmians and Spanish Protestants were persecuted or had to emigrate, among them the translators of the Bible in Spanish, such as Francisco de Enzinas, Casiodoro de Reina and Cipriano de Valera, as well as the Protestant humanists Juan Pérez de Pineda, Antonio del Corro or Juan de Luna, among others.

During the cultural and economic heyday of this era, Spain achieved international prestige throughout Europe. Everything that came from Spain was often imitated; and the learning and study of the language is extended (see Hispanism).

The most cultivated cultural areas were literature, plastic arts, music and architecture. Knowledge accumulates in the prestigious universities of Salamanca and Alcalá de Henares.

The most important cities of this period are: Seville, for receiving the colonial riches and the most important European merchants and bankers, Madrid, as the seat of the Court, Toledo, Valencia, Valladolid (which was the capital of the Kingdom at the beginning of the century XVII) and Zaragoza.

In the field of the humanities, its cultivation was more extensive than deep and more informative than erudite, despite the fact that philology offered eminent testimonies such as the Biblia poliglota complutense (1520) or the Antwerp Polyglot (1572), and the numerous grammars and vocabularies of newly discovered indigenous languages, the work of the many missionary friars who evangelized the newly discovered continent.

Also in the scientific field there were important advances that, for example, in agronomy, came to constitute a revolution. Well, if the Old World contributed to the New the sugar cane, the wheat and the vine; the New brought potatoes, corn, beans, cocoa, tomato, pepper and tobacco to the Old. Linguistics developed remarkably with authors Francisco Sánchez de las Brozas (Minerva). For geography and cartography, the cosmographer Martín Cortés de Albacar discovered the magnetic declination of the compass and the magnetic north pole, which he then located —it moves throughout history— in Greenland, and developed the nocturnal lip; His disciple Alonso de Santa Cruz would invent the spherical letter or cylindrical projection. In anthropology and natural sciences (botany, mineralogy, etc.) the discovery of America provided information about new peoples, species, and phenomena. There were also eminent figures in mathematics, such as Sebastián Izquierdo and his calculation of combination and permutation; Juan Caramuel, responsible for calculating probabilities; Pedro Nunes, discoverer of the loxodrome and inventor of the vernier; Antonio Hugo de Omerique, Pedro Ciruelo, Juan de Rojas y Sarmiento, Rodrigo Zamorano and others.

In the field of medicine and pharmacology, it is worth mentioning the botanist Andrés Laguna; as well as the discovery by the Countess of Chinchón (1638) of the properties against fevers and malaria of quina, predecessor of quinine. In psychology and pedagogy, it is worth mentioning Juan Luis Vives and Juan Huarte de San Juan (Examen de ingenios para las ciencias, 1575); while philosophy saw the rise of Rationalism with Francisco Sánchez the Skeptic and exponents of the School of Salamanca such as Francisco Suárez. Likewise, due to the great impact that the discoveries of new peoples had, natural law and the law of nations were developed, with figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas, influential precursor of human rights and defender of natural law in his De regal potestate; or Francisco de Vitoria.

The Golden Age encompasses two aesthetic periods, corresponding to the Renaissance of the XVI century (Catholic Monarchs, Carlos I and Felipe II), and the Baroque of the XVII century (Felipe III, Felipe IV and Carlos II). The axis of these two epochs or phases can be placed in the Council of Trent and the Counter-Reformation.

Literature

Spain produced in its classical age some characteristic aesthetics and literary genres that were highly influential in the subsequent development of universal literature. Among the aesthetics, the development of a realistic and popularizing style was fundamental, as it had been forging throughout the peninsular Middle Ages as a critical counterpart to the excessive, chivalrous, and noble idealism of the Renaissance: genres as naturalistic as the Celestinesque (Tragicomedy of Calisto and Melibea, Segunda Celestina, etc.), the picaresque novel (The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes, Guzmán de Alfarache , La vida del Buscón or Estebanillo González), or the protean modern polyphonic novel (Don Quixote de la Mancha ), which Cervantes defined it as "unleashed writing".

This literary vulgarization corresponds to a subsequent vulgarization of humanistic knowledge through the popular genres of miscellanies or silvas of various lessons, widely read and translated throughout Europe, and among whose most important authors were Pedro Mejía, Luis Zapata or Antonio deTorquemada.

This anti-classical trend also corresponds to the formula of the new comedy created by Lope de Vega and disseminated through his New art of making comedies in this time (1609): an incomparable explosion of creativity Dramatically accompanied Lope de Vega and his disciples (Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, Tirso de Molina, Guillén de Castro, Antonio Mira de Amescua, Luis Vélez de Guevara, Juan Pérez de Montalbán, among others), who like him broke the Aristotelian units of action, time and place. All the playwrights in Europe then went to the Spanish classical theater of the Golden Age in search of arguments, a rich auction and quarry of modern themes and structures whose polish will offer them works of a classical nature.

At the end of the XVI century, mysticism was notably developed by Juan de la Cruz, Juan Bautista de la Concepción, Juan de Ávila or Teresa de Jesús; and the ascetic, with authors such as Luis de León and Luis de Granada, to decline into the XVII century after a last current innovative, the quietism of Miguel de Molinos.

Many of the literary themes of the 16th century came from the rich and multicultural tradition of the Middle Ages, Arabic and Hebrew, from the romancero and of the Italianate imprint of Spanish culture —because of the political presence of the Spanish kingdom in the Italian peninsula for quite some time—. On the other hand, dramatic genres such as the hors d'oeuvre and the courtly novel also introduced realistic aesthetics in the comedy theaters, and even the swashbuckling comedy had its popular representative in the figure of the funny person.

This current of popularizing realism was followed by a Baroque religious, noble and courtly reaction that also made notable aesthetic contributions, but which already corresponded to a time of political, economic and social crisis. To the clear and popular language of the XVI century, the living Castilian, creator and in perpetual boiling of Bernal Díaz del Castillo and Santa Teresa the darkest, most enigmatic and courtly language of the Baroque will follow. And thus the paradox results that the Spanish literature of the Renaissance of five centuries ago is clearer, more legible and understandable than the literature of the Baroque of only four centuries ago.

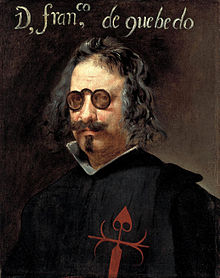

In effect, the literary language of the XVII century becomes rare with the aesthetics of conceptismo and culteranismo, whose purpose was elevate the noble over the vulgar, intellectualizing the art of the word; Literature is transformed into a kind of scholasticism, into a game or a courtly show, although the moralizing and extremely ingenious productions of Francisco de Quevedo and Baltasar Gracián distort the language, giving it more expressive flexibility and a new source of words (cultisms). The lucid Pedro Calderón de la Barca created the formula of the auto sacramental, which supposes the anti-popular and splendid vulgarization of theology, in deliberate antithesis with the hors d'oeuvre, which, however, is still ongoing; for these authors are still indebted to and admirers of the authors of the XVII century, whom they consciously imitate, although in order not to repeat themselves they refine their formulas and courteously stylize what others have already created, in such a way that themes and dramatic formulas already used by other previous authors are perfected. The Calderón school will continue with this model, which they will continue and definitively close, at the beginning of the XVIII century, José de Cañizares and Anthony de Zamora.

Poetry

Spain experienced a great wave of Italianism that invaded literature and the plastic arts during the 16th century, which constitutes one of the identity traits of the Renaissance: Garcilaso de la Vega, Juan Boscán and Diego Hurtado de Mendoza introduced verse Italian hendecasyllabic and the strophism and the themes of Petrarchism; Boscán wrote the manifesto of the new school in the Epístola a la duquesa de Soma and translated The courtier by Baltasar de Castiglione, the ideal of the Renaissance knight, in perfect Castilian prose. Against these rose a nationalist current headed by the nostalgic Cristóbal de Castillejo, resident in Vienna, or Ambrosio Montesino, both supporters of the octosyllable, of the Castilian couplets and of popular inspiration; all were, however, Renaissance.

In the second half of the 16th century, the Italian and the native Castilian tendencies coexisted and ascetics and mystics developed, reaching peaks such as those represented by Saint John of the Cross, Saint Teresa of Jesus and Luis de León, among many others. others that would deserve a long review; Ignacio de Loyola creates the Society of Jesus, which will instruct great scholars throughout Europe in all fields of knowledge and will also promote the study of classical languages. Petrarchism continued to be cultivated by authors such as Fernando de Herrera, and a group of young new authors began to develop a new Romancero, sometimes with a Moorish theme: Lope de Vega, who also developed a cult of traditionalism to through its various songbooks (Rhymes, Sacred Rhymes, La Circe, La Philomela, Human Rhymes and divine...) Luis de Góngora and Miguel de Cervantes, among others; The best learned epic poem in Spanish was composed at this time by Alonso de Ercilla: La Araucana, which narrates the conquest of Chile by the Spanish. In 1584, the year of publication of La Araucana, Francisco Hernández Blasco gave birth to another extensive epic poem in ranches on evangelical subjects, the Universal redemption, which would have numerous subsequent editions and remarkable success. Among the exceptional figures of poetry are poets as interesting as Francisco de Aldana, Andrés Fernández de Andrada, author of the serene and meditative Epístola moral a Fabio, the brothers Bartolomé and Lupercio Leonardo de Argensola, Fernando de Herrera, Francisco de Medrano, Francisco de Rioja, Rodrigo Caro, Baltasar del Alcázar or Bernardo de Balbuena, who in 1624 gave the world the second great learned epic in Spanish, El Bernardo o Victoria de Roncesvalles.

Later, during the XVII century, literary expression was dominated by the aesthetic movements of conceptismo and culteranismo, expressed the first in the poetry of Francisco de Quevedo, mainly satirical, moral and philosophical-existential, and the second in the lyric of Luis de Góngora (the Sonetos, the Fable of Polifemo and Galatea and especially its Soledades). Conceptism was distinguished by the economy in form, in order to express the maximum meaning in a minimum of words; this complexity was expressed above all in paradoxes and ellipses. The culteranismo, on the contrary, extended the form of a minimal meaning and was distinguished by its syntactic complexity, by the constant use of the hyperbaton, which makes reading very difficult, and by the profusion of ornamental and culturalist elements in the poem, that had to be deciphered like an enigma. Both seem, however, the sides of the same coin that tried to refine the expression to make it more difficult and courteous. Luis de Góngora attracted important poets with very marked personalities to his style, such as the Count of Villamediana, Gabriel Bocángel, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz or Juan de Jáuregui, while conceptism had more temperate followers, such as the Count of Salinas or imbued with a cultured traditionalism, such as Lope de Vega or Bernardino de Rebolledo.

Theater

In the Golden Age, the "monster of nature", as Cervantes called it, was Lope de Vega, also known as "the Phoenix of Wits", author of more than four hundred plays, as well as novels, epic and narrative poems and various collections of profane, religious and humorous lyric poetry. Lope stood out as an accomplished master of the sonnet. His contribution to the universal theater was mainly a prodigious imagination, from which his contemporaries, Spanish and European successors took advantage, extracting themes, arguments, motifs and all sorts of inspiration. His polymetric theater breaks with the units of action, place, time, and also with style, mixing the tragic with the comic. He expounded his peculiar dramatic art in his New Art of Making Comedies in This Time (1609). He relaxed the classicist norms of Aristotelianism to adapt to his time and thereby opened the doors to the renewal of dramatic art. He also created the mold for the so-called swashbuckling comedy. In palatal comedy, he was the author who most resorted to the setting in the Kingdom of Hungary, a resource that would become frequent in the literature of the time. Lope's cycle of Hungarian comedies consists of around twenty plays.

Along with him, his disciples Guillén de Castro stand out, who dispenses with the comic character of the funny and elaborates great chivalrous dramas about honor together with comedies of conjugal unhappiness or tragedies in which tyrannicide is dealt with; Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, who contributed his great ethical sense of criticism of social defects and great mastery in the characterization of the characters; Luis Vélez de Guevara, who was very good at great historical and honor dramas; Antonio Mira de Amescua, highly educated and prolific in philosophical ideas, and Tirso de Molina, a master in the art of diabolically complicating the plot and creating characters like Don Juan in The mocker of Seville and stone guest.

Representative masterpieces of Spanish golden theater include Numancia by Miguel de Cervantes, a sober national heroic drama; Lope's El caballero de Olmedo, a poetic drama on the very edge of the fantastic and full of heavenly resonances; Peribáñez and the Commander of Ocaña, antecedent of Spanish rural drama; The manger's dog, a delicious comedy where a noblewoman plays with the amorous intentions of her commoner secretary, The silly lady, where love perfects the beings it martyrs, and Fuenteovejuna, a collective honor drama, among many other pieces where there is always a great scene.

Las mocedades del Cid by Guillén de Castro, inspiration for the famous «Cornellian conflict» of Le Cid by Pierre Corneille; Reinar después de muerte by Luis Vélez de Guevara, on the theme of Inés de Castro, who became a European drama with this work; The Suspicious Truth and The Walls Hear, by Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, which attack the vices of hypocrisy and gossip and served as inspiration for Molière and other French playwrights; The Demon's Slave by Antonio Mira de Amescua, on the subject of Faust; Prudence in women, which explores the theme of repeated betrayal and where the strong character of the regent queen María de Molina appears, and The mocker of Seville, by Tirso de Molina, on the theme of the ladyboy and the legend of the stone guest.

The other great golden playwright to create his own school was Calderón de la Barca; His characters are cold reasoners and often obsessive; his versification consciously reduces Lope de Vega's metrical repertoire and also the number of scenes, because the dramatic structures are more careful and tend towards synthesis; he is also more concerned than Lope with the set elements and recasts previous comedies, correcting, deleting, adding and perfecting; he is a master in the art of syllogistic reasoning and uses an abstract, rhetorical and elaborate language that nevertheless supposes an understandable vulgarization of culteranismo; He especially stands out in the auto sacramental, an allegorical genre that matched his qualities and led to his perfection, and also in comedy.

Calderón's masterpieces include Life is a dream, on the themes of free will and destiny; The constant prince, where an existential conception of life appears; the two parts of The daughter of the air, the great tragedy of ambition in the person of Queen Semiramis; the great dramas of honor about characters driven mad by jealousy, such as The biggest monster in the world , The doctor of his honor or The painter of the dishonor of he . Among his comedies, The Goblin Lady stands out, and he also cultivated mythological dramas such as Céfalo and Procris , from which he himself drew the burlesque comedy of the same title; also, sacramental plays such as The great theater of the world or The great market of the world that captivated the imagination of the English and German romantics.

His disciples and imitators of these qualities were a series of authors who recast previous works by Lope or his disciples, polishing and perfecting them: Agustín Moreto, master of dialogue and courtly humor; Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla, as gifted for tragedy as for comedy; Antonio de Solís, also a historian and owner of a prose that is already neoclassical, or Francisco Bances Candamo, drama theorist, among others no less important.

Among his disciples we have the classic comedies of Agustín Moreto, such as the palatal comedy El desdén, con el desdén, the figurón one El lindo don Diego and the religious drama San Franco de Sena, which refers to El condenado por distrusto de Tirso de Molina; Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla with the figurón comedy Among bobos anda el juego, the honor drama None of the king below and the delicious and modern comedy Open your eye. By Antonio de Solís, El amor al uso and A fool makes a hundred; by Francisco Bances Candamo, the political tragedies The Slave in Golden Shackles and The Philosopher's Stone.

Another important theatrical genre, and sometimes neglected by critics, is the entremés, where Spanish society during the Golden Age can be better and more objectively studied. It is a comic piece in one act, written in prose or verse, which was inserted between the first and second day of the comedies. It corresponds to the European farce, and authors such as Luis Quiñones de Benavente and Miguel de Cervantes, among others, stood out in it.

Prose

Prose in the Golden Age boasts genres and authors that have gone down in the history of universal literature. The conquest of America gave rise to the Chronicles genre, among which we can find some masterpieces, such as those by Bartolomé de las Casas, the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas and Antonio de Solis. Some autobiographies of soldiers are also splendid, such as those of Alonso de Contreras or Diego Duque de Estrada. The first masterpiece was undoubtedly La Celestina, an unrepresentable and highly original theatrical piece by an unknown author and by Fernando de Rojas, which, along with its continuations by other authors (the so-called Celestinesque genre) or its free imitations (among them the prodigious La Lozana andaluza (1528), a masterpiece by Francisco Delicado) forever marked Realism in an essential part of Spanish literature, whose wealth also fertilizes chivalrous fictions as marvelous and fantastic like books of chivalry, less widely read today than they deserve, considering that novels such as Tirante el Blanco, written in Valencian, Amadís from Gaula or the Palmerín from England; a characteristic author of the genre was Feliciano de Silva.

The sentimental novel opens and closes in half a century with two masterpieces: Cárcel de amor (1492) by Diego de San Pedro and Proceso de letras de amores (1548), an epistolary novel by Juan de Segura (1548). Along with these, we must also mention two other masterpieces of the Moorish novel genre: the Historia del Abencerraje y de la hermosa Jarifa (1565) and Ozmín y Daraja by Mateo Alemán (1599).

The picaresque novel has among its greatest creations, masterpieces such as the anonymous Lazarillo de Tormes (1554), an anticlerical and stark satire of the airs of nobility and the sense of honor of the class high; Life of the rogue Guzmán de Alfarache (1599 and 1604) by Mateo Alemán, a pessimistic reflection on human destiny; the Life of the squire Marcos de Obregón (1618) by Vicente Espinel, filled on the contrary with the joy of life; The life of the Buscón (1604-1620) by Francisco de Quevedo, a masterpiece of humor and conceptual language, the anti-clerical Second part of the life of Lazarillo (1620) by the Protestant Juan de Luna, and the enigmatic work by Estebanillo González (1646), which offers a splendid vision of the decline of Spain on the European stage, and of the Thirty Years' War. The courtly novel provided the masterpieces that constitute the Exemplary Novels (1613) of Miguel de Cervantes, each one in itself a narrative experiment; his immortal Don Quixote de la Mancha (1605 and 1615), which would have to be written a separate chapter because of the richness of the content and issues it raises, which is the first polyphonic novel by European literature. The pastoral novel includes masterpieces such as the Dianas by Jorge de Montemayor (1559 and 1604) and Gaspar Gil Polo (1564), La constante Amaryllis (1607) by Cristóbal Suárez de Figueroa or Golden Age in the Jungles of Erifile (1608) by Bernardo de Balbuena. The Byzantine novel has examples such as The pilgrim in his homeland (1634) by Lope de Vega, who accomplished the feat of including all his adventures in the Peninsula, the Persiles (1617) by Cervantes or the Prodigious Lion (1634) by Cosme Gómez Tejada de los Reyes.

A philosophical novel related to this genre is the Criticón (1651, 1653 and 1657), by Baltasar Gracián, an allegory of human life. The doctrinal prose, in the making of essays, has exemplary authors such as Pero Mexía, Luis Zapata, Antonio de Guevara (Epístolas familiares, 1539, Relox de príncipes, 1539), Luis de León (Of the names of Christ), Saint John of the Cross (Comments to the Spiritual Song and other poems), Francisco de Quevedo (Marco Bruto and Providencia de Dios) and Diego Saavedra Fajardo (Literary Republic and Gothic Crown).

Transcendence

Jean Rotrou (1609-1650) and Paul Scarron (1610-1660) achieved great success translating or imitating Spanish authors, and they influenced major French dramatists such as Pierre Corneille and Molière, not to mention others of minor importance, such as Thomas Corneille, Alain René Lesage, John Vanbrugh etc. Spanish plays spread their influence by being translated, for example, in Holland (by Theodore Rodenburg) and England (John Webster, Fletcher, Dryden, etc.).

Philosophy

The philosophy of the Spanish Golden Age encompasses all the thought that goes from the first humanism to the establishment of rationalism in the 18th century. Despite the fact that three religions coexisted in Spain (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), it is true that a philosophy developed that would culminate in the Baroque period. In this way, the philosophy of the Golden Age is divided into two sections: that of the Renaissance and that of the Baroque.

During the Renaissance, we find Spain's first great humanist, Antonio de Nebrija, with his Spanish grammar. Nebrija managed to create the first rules of the language that would later be so widely disseminated with the subsequent founding of the Royal Spanish Academy (1713). On the other hand, the great patron during humanism was Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, who put his efforts into reforming clerical customs. In 1499 he founded the University of Alcalá de Henares, which surpassed in prestige and influence all others except that of Salamanca, his greatest rival.

Carlos I defended the new theories of Erasmus of Rotterdam and the new humanist current. A faithful follower of Erasmus was Juan Luis Vives. He became a reformer of European education and a moralist philosopher of universal stature, proposing the study of Aristotle's works in their original language and adapting his books for the study of Latin to students; he replaced the medieval texts with new ones, with a vocabulary adapted to his time and the way of speaking of the moment and made the first contributions to a science in germ, psychology.

The new discoveries in the New World and the Spanish colonization of the Indies led some thinkers to reflect on the treatment that the indigenous people deserved. The controversies were raised by the Dominican Fray Bartolomé de las Casas in his Brief account of the destruction of the Indies , where he described the Spanish colonization of America with horrific overtones and defended natural law. The content of the letter led to a dispute between 1550 and 1551 in Valladolid against his main opponent, Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, who defended customary law, the kindness of Spanish colonization and the law of war. This dispute came to be called the "Junta de Valladolid."

The University of Salamanca made a decisive contribution to universal political, economic and moral thought. The resurgence of the new spirit is seen embodied in the main figure with Francisco de Vitoria, Dominican theologian, professor of Salamanca, who rejected all arguments based on purely metaphysical considerations for being in favor of the study of the real problems posed by political and social life. contemporary. He was the first to establish the basic concepts of modern international law, based on the rule of natural law. He thus affirmed fundamental freedoms such as speech, communication, trade and transit through the seas, provided that nations and races did not harm each other.

Christianity in Spain gave its own thinkers and theologians, most of them orthodox through the Counter-Reformation, but also heterodox in a Reformation that could only take hold abroad. As for the Orthodox, Saint Ignatius of Loyola stands out, who wrote his Spiritual Exercises and founded the Society of Jesus, with which he wanted to achieve religious unity and who, with his network of schools, renewed the teaching classical languages. In poetry, very deep and personal movements of asceticism and mysticism developed. The lyric of the Renaissance is characterized by having a group of religious who transmitted their philosophy through poetry. It is worth noting Saint John of the Cross, Saint Teresa of Jesus and F as eminent figures among a large group of important figures.

The arrival of the Baroque completely changed the Renaissance mentality of humanism. The vision of life became pessimistic and all perspectives ended in disappointment. The philosophical prose shines with Luis de Molina, enlightened established in Rome. His doctrine, nicknamed Molinism, had a great impact and influence on Baroque thinkers and writers after him. His thought mixes the principles of religion with an elaborate moral philosophy. Molina fought determinism with free will. His works on freedom were widely followed by the thinkers of the following century.

The philosopher and physician Gómez Pereira rejects medieval concepts to defend the empirical methods on which the science of the following two centuries would be based. He is considered, along with the skeptic Francisco Sánchez, one of the forerunners of René Descartes and influenced his later works, being the first to suggest the automatism of beasts, the theory of human knowledge and the immortality of the soul. [citation required]

The University of Salamanca also contributed a lot to early Baroque thought. Melchor Cano wrote De Locis Theologicis, a work in which he established the ten sources for theological demonstration: Sacred Scripture, apostolic tradition, the authority of the Catholic Church, the authority of ecumenical councils, the authority of the Supreme Pontiff, the doctrine of the Fathers of the Church, the doctrine of scholastic doctors and canonists, rational human truth, the doctrine of philosophers and history.

In the transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque is Francisco Suárez, a man of extraordinary culture and wise in classical aspects. He continued the Thomistic doctrine in a versatile way. In his great philosophical and legal work De legibus ac Deo legislatore , very fruitful for the doctrine of natural law and international law, the idea of the social pact is already found. Suárez is one of the summits of European philosophy.

With anthropology great advances were made. The main figure was José de Acosta, who advanced the theory of Darwinian evolution by three centuries.

Plastic arts

Painting

In the plastic arts, painting stands out. Pedro Berruguete, Pedro Machuca, Luis de Morales, the Leonardesques Juan de Juanes and Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina correspond to a first phase. To the second, Juan Fernández de Navarrete, Alonso Sánchez Coello and El Greco, the main exponent of pictorial mannerism in Castile.

Diego Velázquez belongs to the Baroque, a painter of complex intellectualized compositions who delves into the mystery of harsh and intense light and aerial perspective; the Caravaggian tenebrists Francisco de Zurbarán (great painter of friars and still lifes), Francisco Ribalta and José de Ribera; In Seville, it is worth mentioning Francisco Herrera el Viejo and Francisco Herrera el Mozo, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo and Juan de Valdés Leal; while in Córdoba Antonio del Castillo stands out and in Granada Alonso Cano.

It is also worth mentioning Juan Bautista Maíno (painter of political allegories), Claudio Coello, Juan Carreño de Miranda, the Florentine Vicente Carducho, the portraitist Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, Luis Tristán (one of the few disciples of El Greco, who adds naturalist elements to the style of the master), Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo, Pedro Orrente, Bartolomé González y Serrano, the Carthusian Juan Sánchez Cotán (famous for his mystical still lifes), Eugenio Cajés, Antonio Pereda; Mateo Cerezo, the landscaper Francisco Collantes, Juan Antonio Frías y Escalante, José Antolínez, the Aragonese Jusepe Martínez and many others.

Sculpture

Regarding sculpture, we already have in the Pre-Renaissance and early years of the XVI century the foreign figures who worked in Spain: Domenico Fancelli, Pietro Torrigiano and Jacopo Florentino. The first generation of Spanish sculptors of the Renaissance in Castile was made up of Vasco de la Zarza (retrochoir of the Cathedral of Ávila), Felipe Vigarny (high altarpiece of the Cathedral of Toledo), Bartolomé Ordóñez (choir stalls of the Cathedral of Barcelona) and Diego de Siloé (tomb of Don Alonso de Fonseca y Acevedo in the Convent of Las Úrsulas in Salamanca); In the Crown of Aragon, the work of Damián Forment (main altarpiece of the Basilica del Pilar, 1509 and of the Poblet monastery, 1527), Gil Morlanes el Viejo (doorway of the church of Santa Engracia in Zaragoza) and Gabriel Yoly, who he carved in wood without polychrome the main altarpiece of the cathedral of Teruel in 1536.

In mannerism one must of course mention the correlate of asceticism and mysticism of the second half of the XVI century. The great Alonso Berruguete, the Galician Gregorio Fernández, the Italian classicist sculptors Leone Leoni and his son Pompeyo Leoni (who worked for the Royal Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial); the Baroque Francisco del Rincón and Pedro Vicálvaro, from the Castilian School, and Juan de Juni; from the Andalusian School Jerónimo Hernández, Andrés de Ocampo, Juan Martínez Montañés, Juan de Mesa, Francisco de Ocampo y Felguera, Alonso Cano. In the middle of the Baroque they already led to sculptors such as Pedro de Mena, Pedro Roldán, his daughter Luisa Roldán and his grandson Pedro Duque y Cornejo; Francisco Ruiz Gijón, José Risueño, Bernardo de Mora or his son José de Mora. From Guipúzcoa came Juan de Ancheta, in a Roman classicist style, whose work was carried out mainly in Navarra, La Rioja and Aragón. The theme dealt with is almost exclusively religious and monumental sculpture is only given in the area of the Court; mythological and secular themes are absent. Altarpieces are made, where free-standing and bas-relief figures appear. The wooden imagery of the Hispanic tradition stands out. In these works the stew technique is lost and polychromy will be used later. The figures are isolated: for churches, convents and for Holy Week processions.

Music

This was also the golden age for Spanish music. The work of courtly composers, who combined their work as a musician with that of a playwright and poet, has a good example in Juan del Encina in the century. XV and XVI; or in the 17th century Juan Hidalgo, who set music for Calderón de la Barca's zarzuelas, as did Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco. In the time of Charles V they composed Mateo Flecha the Elder, author of Las Salads (Prague, 1581), a genre that mixes verses in different languages. Cristóbal de Morales studied in Rome, where he published some masses in 1544. Other musicians were Pedro de Pastrana, Juan Vázquez or Diego Ortiz.

At the time of Felipe II correspond Francisco Gabriel Gálvez, Andrés de Torrentes, Juan Navarro or Rodrigo de Ceballos. Francisco Guerrero worked in Seville, who traveled to Italy and published his work between 1555 and 1589.

But even more important was the work of composers or, as they were called at the time, chapel maestros and organists who, based on Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina's Italian motet and madrigal, developed a great polyphony at the service, above all, of religious services, with a great emotional charge that distinguished it from the other three great polyphonic schools of the 15th to the 17th centuries, such as the Flemish, Venetian and Roman Schools, and which has been linked to the mystical passion of writers like Teresa de Ávila or Juan de la Cruz. The already mentioned figures of Cristóbal de Morales, Francisco Guerrero, and other previous ones such as Francisco de Peñalosa, Morales' teacher, and later ones, such as Alonso Lobo but above all that of the great Tomás Luis de Victoria, majestic, inspired and mystical, stand out. Its depth and ascetic emotion have been compared to the painting of El Greco, and today, thanks to the work of scholars and disseminators of his music such as Jordi Savall, he is recognized as one of the greatest composers of all time. In Rome, where he worked mainly, he published some 170 works—65 motets, 34 masses, 37 Easter offices, the Magnificat, and Psalms—since 1572. 1587 works for the Empress, at whose death he composed a famous Officium Defunctorum (1605) for six voices. His polychoralism (compositions for two choirs) and care for harmony, in the writing of flats and sharps, mark him as a precursor of the Baroque.

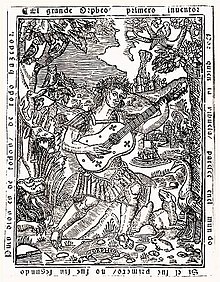

The Spanish vihuela school of the XVI century stands out. Great figures appeared, such as Esteban Daza, Luys de Milán (author of El Maestro, 1536, which includes fantasies, pavanas, tientos, villancicos, romances and original works in which the vihuela admits singing), Alonso Mudarra (with his Three books of encrypted music for vihuela, Seville, 1546), Luis de Narváez (El Delphín, 1538), Enríquez de Valderrábano (Silva de Sirenas, 1547), Diego Pisador (Libro de música de vihuela, 1552), Miguel de Fuenllana (Orphénica Lyra) and Gaspar Sanz, already in the last quarter of the XVII century, who gave a definitive boost to the guitar with his work Music Instruction on the Guitar Spanish.

For his keyboard work, Antonio de Cabezón from Burgos gained fame in the XVI century, and Juan Bautista Cabanilles and Francisco Correa de Arauxo, in the 17th century. The classic works in this regard are the Obras de música para tecla, harpa y vihuela (1578) by Antonio de Cabezón, prepared by his son, and El Libro de Cifra Nueva for keyboard, harp and vihuela (Alcalá de Henares, 1557) by Luis Venegas de Henestrosa: both show the versatility of these compositions to adapt to instruments or human voices.

All of them shaped a period of splendor for Spanish music, which, except for isolated figures, never again reached the heights reached at this time. However, much of this musical heritage has been lost and, for example, of the work of Francisco de Salinas, which so delighted Fray Luis de León, no sheet music has been preserved, only a theoretical treatise.

Architecture

In the 16th century there was a change from the Plateresque style of the Renaissance during the Catholic Monarchs to the more fully Renaissance style during the reign of Carlos I; later, during that of his son Felipe II, the Mannerism of Juan de Herrera emerged, creator of the Herrerian Style and the monumental monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial and the unfinished cathedral of Valladolid, and during the XVII dominates the Baroque and Churrigueresque.

In Spain, the Renaissance began together with Gothic forms in the last decades of the 15th century. The style began to spread mainly at the hands of local architects: it is the reason for a specifically Spanish Renaissance style, which brought together the influence of southern Italian architecture, sometimes coming from illustrated books and paintings, with the Gothic tradition and the local idiosyncrasy. The new style is called Plateresque, due to the excessively decorated facades, reminiscent of the intricate works of silversmiths. Classical orders and candlestick motifs (candelieri) are freely combined in symmetrical ensembles.

In this context, the Palace of Carlos V by Pedro Machuca, in Granada, was an unexpected achievement within the most advanced Renaissance of the time. The palace can be defined as an anticipation of mannerism, due to its mastery of classical language and its breakthrough aesthetic achievements. It was built before major works by Michelangelo and Andrea Palladio. His influence was very limited and misunderstood, Plateresque forms were imposed on the general scene.

As the decades passed, the Gothic influence disappeared and the search for an orthodox classicism reached very high levels. Although Plateresque is a term commonly used to define most of the architectural production of the late XV century and first half of the In the 16th century, some architects acquired a more sober taste, such as Diego de Siloé, Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón and Gaspar de Vega. Examples of Plateresque are the facades of the University of Salamanca, the Colegio Mayor Santa Cruz in Valladolid and the Hostal San Marcos in León.

The pinnacle of the Spanish Renaissance is represented by the Royal Monastery of El Escorial, carried out by Juan Bautista de Toledo and Juan de Herrera, in which an excessive adherence to the art of ancient Rome was overcome by the extremely sober style. The influence of the Flemish ceilings, the symbolism of the scant decoration and the precise cut of the granite established the base for a new style, the Herrerian style.

With a style closer to Mannerism, the century closed with architects such as Andrés de Vandelvira (Cathedral of Jaén).

When Italian Baroque influences reached Spain, they gradually replaced in popular taste the sober classicist taste that had been in fashion since the 18th century XVI. As early as 1667, the facades of the Granada Cathedral by Alonso Cano and that of Jaén by Eufrasio López de Rojas indicate the ease of his interpretation in the Baroque manner of the traditional motifs of Spanish cathedrals.

The local baroque maintains its roots in Herrera and in traditional brick construction, developed in Madrid throughout the XVII century (Plaza Mayor and Madrid City Hall).

Contenido relacionado

Kingdom of Navarre

Willem Kalf

1648