Gnosticism

Gnosticism (from ancient Greek: γνωστικός gnōstikós, "to have knowledge") is a set of ancient religious ideas and systems that originated in the 1st century between Jewish and ancient Christian sects. These various groups emphasized spiritual knowledge (gnosis) over orthodox teachings and traditions and the authority of the church. Viewing material existence as flawed and malevolent, Gnostic cosmogony generally draws a distinction between a hidden, supreme God, and a malevolent, lesser deity (sometimes associated with Yahveh (Jehovah) in the Old Testament) who is responsible for creating the world. material universe. The Gnostics considered that the main element of salvation was the direct knowledge of the supreme divinity in the form of mystical or esoteric intuitions. Many Gnostic texts discuss not the concepts of sin and repentance, but those of illusion and enlightenment.

Some of these philosophical-religious syncretic currents came to blend with Christianity in the first three centuries of our era, finally becoming a thought declared heretical by the Church after a stage of certain prestige among some Christian intellectuals. Indeed, one can speak of a pagan Gnosticism and a Christian Gnosticism, although the most significant Gnostic thought was reached as a heterodox branch of primitive Christianity. According to this doctrine, the initiates are not saved by faith in forgiveness thanks to the sacrifice of Christ, but rather they are saved through gnosis, or introspective knowledge of the divine, which is knowledge superior to faith. Neither faith alone nor the death of Christ are enough to be saved. The human being is autonomous to save himself. Gnosticism is an esoteric mysticism of salvation. Orientalist beliefs and ideas of Greek philosophy, mainly Platonic, are syncretically mixed. It is a dualistic belief: good versus evil, spirit versus matter, the supreme being versus the Demiurge, spirit versus body and soul. The term comes from the Greek Γνωστηκισμóς (gnostikismós); from Γνῶσις (gnosis): 'knowledge'.

Gnostic writings flourished among certain Christian groups in the Mediterranean world until the mid-II century, when the early fathers of the church denounced them as heresy. Efforts to destroy these texts were generally successful, resulting in very little of the writings of Gnostic theologians surviving. However, ancient Gnostic teachers such as Valentine saw their beliefs as compatible with the Christianity. Christ is seen as a divine being who has taken human form to lead humanity back into the Light. However, Gnosticism does not refer to a single standardized system, and the emphasis on direct experience allows room for a wide variety. of teachings, including different currents such as Valentinianism or Setianism, or later currents such as Catharism. In the Persian Empire, Gnostic ideas spread even as far as China through the related movement called Manichaeism, while Mandeism is still alive in Iraq.

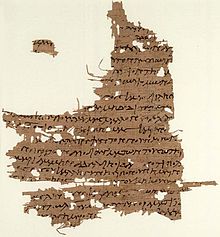

For centuries, most scholarly knowledge of Gnosticism was limited to the anti-heretical writings of orthodox Christian figures such as Saint Irenaeus of Lyons and Hippolytus of Rome. A renewed interest in Gnosticism occurred after the discovery, in 1945, of the Nag Hammadi Library in Egypt; a collection of rare and ancient Christian and Gnostic texts, including the Apocryphal Gospel of Thomas and the Apocryphon of John. An important issue in academic research is the description of Gnosticism as either an interfaith phenomenon or as an independent religion. Scholars have acknowledged the influence of sources such as Hellenistic Judaism, Zoroastrianism, and Platonism, and some have noted possible links to Buddhism and Hinduism, although evidence of direct influence from these latter sources is not conclusive.

Etymology

Gnosis refers to knowledge based on personal experience or perception. In a religious context, gnosis is mystical or esoteric knowledge based on direct involvement with the divine. In most Gnostic systems, the sufficient cause of salvation is this "knowledge of" ("familiarity with") the divine. It is a "knowing" interior, comparable to that invited by Plotinus (Neoplatonism), and differs from proto-orthodox Christian perspectives. Gnostics are "those who are oriented toward knowledge and understanding—or perception and learning—as a particular way of life." The usual meaning of gnostikos in classical Greek texts is "cult" (learned or educated) or "intellectual," as used by Plato in the comparison between "practical" (praktikos) and "intellectual" (gnostikos). The Platonic use of "cult" or "learned" It is typical of classical texts.

By the Hellenistic period, the term became associated with the Greco-Roman mysteries, becoming a synonym for the Greek term musterion. The adjective Gnostic is not used in the New Testament, but Clement of Alexandria speaks of the "cultured" (gnostikos) in glowing terms. The use of gnostikos in connection with heresy originates with the interpreters of Irenaeus. Some scholars consider that Irenaeus sometimes uses the word gnostikos to simply mean "intellectual," while the mention of him from the & # 34; intellectual sect & # 34; is a specific designation. The term "gnosticism" it does not appear in ancient sources, and was first coined in the 17th century by Henry More in a commentary on the seven letters from the Book of Revelation, where More uses the term "Gnosticisme" to describe the heresy at Thyatira. "intellectual") by Saint Irenaeus (c. 185) to describe the school of Valentine as "he legomene gnostike haeresis," the heresy called Learned (Gnostic)."

Origins

The origins of Gnosticism are obscure and still a matter of debate today. Proto-orthodox Christian groups called the Gnostics a heresy of Christianity, but according to modern scholars the origin of Gnostic theology is closely related to Jewish sectarian milieus and early Christian sects. Scholars debate whether the origins of Gnosticism have roots in Neoplatonism and Buddhism, due to similarities in their beliefs, but their origin is currently unknown. As Christianity developed and became more popular, so did Gnosticism, and proto-orthodox Christian groups and Gnostic Christian groups often coexisted in the same places. Gnostic belief was widespread within Christianity until proto-orthodox Christian communities ousted the group in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. Gnosticism thus became one of the first groups to be declared heretical.

Some scholars prefer to speak of “gnosis” to refer to the ideas of the I century that would later develop in the gnosticism, reserving the term “gnosticism” for the synthesis of these ideas into a coherent movement in the II century. From According to James M. Robinson, no Gnostic text clearly predates Christianity, and "pre-Christian Gnosticism as such is hard to find in such a way that the debate can be definitively closed." However, the Nag Hammadi Library contained hermetic teachings that can be disputed as to whether they date back to the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2686-2181 BCE).

Judeo-Christian origins

Contemporary scholars tend to agree that Gnosticism has Judeo-Christian origins, originating in the late I century in non-rabbinic Jewish sects and early Christian sects.

Many of the leaders of the Gnostic schools were identified by the early church fathers as Jewish Christians, and the Hebrew words and names of God were applied in some Gnostic systems. Cosmogonic speculations among Gnostic Christians were based at least partly in the Jewish mystical texts of the Maaseh Breishit and the Maaseh Merkabah. This thesis is proposed in particular by Gershom Scholem (1897-1982) and Gilles Quispel (1916-2006). Scholem found traces of Jewish gnosis in the imagery of the Merkabah, which can also be found in "Christian" Gnostic documents, for example in the being "taken" to the third heaven mentioned by the Apostle Paul. Quispel sees Gnosticism as an independent Jewish development, tracing its origins to the Alexandrian Jews, a group with which Valentine was also connected.

Many of the Nag Hammadi texts make reference to Judaism, in some cases with a violent rejection of the Jewish God. Gershom Scholem once described Gnosticism as "the greatest case of metaphysical anti-Semitism." Professor Steven Bayme he stated that Gnosticism should be better characterized as anti-Judaism. Recent research on the origins of Gnosticism shows strong Jewish influence, particularly from the Hekhalot literature.

Within early Christianity, the teachings of Paul and John may have been a starting point for Gnostic ideas, with increasing emphasis on the opposition between flesh and spirit, the value of charisma, and the disqualification of Jewish law. The mortal body belonged to the world of lower and mundane powers (the archons), and only the spirit or soul could be saved. The term gnostikos may have acquired greater meaning there.

Alexandria was of central importance to the birth of Gnosticism. The Christian ecclesia (i.e., congregation, church) was Judeo-Christian in origin, but also attracted Greek members, and various currents of thought were available, such as “Jewish apocalypticism, speculation about divine, Greek philosophy, and the Hellenistic mystery religions."

In relation to the angelic Christology of some early Christians, Darrell Hannah points out that:

“[Some] primitive Christians understood ontologically the pre-incarnated Christ as an angel. This chrysthology of the “true” angel took many forms and may have already appeared at the end of the 1st century, if in fact this is the perspective to which the first chapters of the Letter to the Hebrews. The Elcesaites, or at least the Christians influenced by them, paired the male Christ with the female Holy Spirit, seeing them both as two giant angels. Some Valencian Gnostics assumed that Christ assumed an angelic nature and could be the Savior of angels. The author of the Testament of Solomon He argued that Christ was a particularly effective ‘frustrating’ angel in the exorcism of demons. The author of De Centesima and the ‘Ebionitas’ of Epifanio argue that Christ has been the highest and most important of the archangels created first, a similar perspective in many respects to the equation made by Hermas of Christ and Michael. Finally, a possible exegetic tradition behind the Ascension of Isaiah and corroborated by the Hebrew master of Origen, can testify about another angelic Christology, as well as an angelic pneumatology. ”

The Christian pseudepigraphical text The Ascension of Isaiah identifies Jesus with angelic Christology:

[Christ the Lord is commissioned by the Father] And I heard the voice of the Highest, the father of my Lord when he told my Lord Christ who will be called Jesus, ‘Go and go down through all the heavens...’

The Shepherd of Hermas is a Christian literary work that was considered canonical writing by some of the early church fathers such as Irenaeus. Jesus is identified with angelic Christology in parable 5, when the author mentions a Son of God, as a virtuous man filled with a Holy "pre-existent spirit."

Neoplatonic influences

Gnostic connections with Neoplatonism were first proposed in the 1880s. Ugo Bianchi, who organized the 1966 Messina Congress on the origins of Gnosticism, also proposed Orphic and Platonic origins. Gnostics took up various ideas and important terms of Platonism, using Greek philosophical concepts throughout his texts, including concepts such as hypostasis (reality, existence), ousia (essence, substance, being), and demiurge (creator God). Both the Setian and Valentinian Gnostics seem to have been influenced by Plato, by Middle Platonism, and by the Neo-Pythagorean academies or schools of thought. The two schools attempted "an effort towards conciliation, even affiliation" with later ancient philosophy, efforts in which they were rejected by some Neoplatonists, including Plotinus.

Persian origins or influences

Early research on the origins of Gnosticism suggested Persian origins or influences, spreading to Europe and incorporating Jewish elements. According to Wilhelm Bousset (1865–1920), Gnosticism was a form of Iranian and Mesopotamian syncretism, and Richard August Reitzenstein (1861–1931) famously located the origins of Gnosticism in Persia.

Carsten Colpe has analyzed and criticized Reitzenstein's Iranian hypothesis, showing that many of his hypotheses are untenable. However, Geo Widengren (1907–1996) proposed that the origin of (Mandeist) Gnosticism lay in Zoroastrian Zurvanism (Mazdean), in conjunction with ideas from the Aramaic Mesopotamian world.

Buddhist Parallels

In 1966, at the Median Congress, the buddhologist Edward Conze noted phenomenological commonalities between Mahayana Buddhism and Gnosticism, in his article Buddhism and Gnosis, following an earlier idea advanced by Isaac Jacob Schmidt. The influence of Buddhism in any sense on either the gnostikos Valentin or the Nag Hammadi texts (III) has not received support in modern research, although Elaine Pagels (1979) called it a "possibility".

Features

Christian Gnosticism, pagan in its roots, came to present itself as a representative of its purest tradition. The Gnostic text of Eugnostos the Blessed seems to date from before the birth of Jesus of Nazareth.

The enormous diversity of doctrines and "gnostic schools" makes it difficult to speak of a single Gnosticism. Some common aspects of their thinking, however, could be:

- Its initiatic character, by which certain secret doctrines of Christ or the "ungido" were intended to be revealed to an elite of initiates. Thus, Christian Gnostics claim to constitute special witnesses of Christ, with direct access to the knowledge of the divine through the gnosis or introspective experimentation through which the knowledge of transcendental truths could be reached. La gnosis It was, therefore, the supreme form of knowledge, only within the reach of initiates.

- The same knowledge of the transcendent truths produced salvation. According to the various currents, the importance of practicing a Christian life could vary, being in any case something secondary.

- Its dualistic character, by which a sharp split was made between matter and spirit. Evil and perdition were linked to matter, while the divine and salvation belonged to the spiritual. For that reason there could be no salvation in matter or body. The human being could only access salvation through the little spark of divinity that was the spirit. Only through the consciousness of one's own spirit, of his divine character and of his introspective access to the transcendent truths about his own nature could he be freed and saved. This almost empirical experimentation of the divine was gnosis, an inner experience of the spirit. Here you can see in Plainism a clear antecedent of Gnosticism, both in its matter-spirit dualism, and in its instrospective form of accessing higher knowledge, being the gnosis a religious version of the Mayatic of Socrates. This dualism also prefigures the future manifoldism.

- His peculiar Christology: Being matter the anchor and origin of evil, it is not conceivable that Jesus Christ could be a divine being and be associated with a material body at once, since matter is contaminating. For that reason the doctrine of the Apparent Body of Christaccording to which the Divinity could not come in the flesh, but came in the spirit, showing to men a material "apparently" body (doceticism). Other currents hold that Jesus Christ was a vulgar man who at the time of his ministry was lifted, adopted by a divine force (adoptionism). Other doctrines affirm that the true mission of Christ was to transmit to human spirits the principle of self-knowledge that allowed souls to be saved by themselves by freeing themselves from matter. Other teachings even suggested that Jesus was not a divine being.

- Peculiar teachings on divinity. Among these was that every spirit was divine, including the spiritual part of man (the soul), who did not need anyone to save himself, being Christ sent to reveal that truth. On the other hand, the creator/orderer of matter (called Demiurgo), by multiplying with his creation matter, would be an evil and opposite to the true Supreme Being of which it arose.

- Very divergent ethical conclusions: Following the idea of condemnation of matter, some currents stated that the punishment and martyrization of the body was necessary to, through the suffering of the flesh, contribute to the liberation of the spirit, advocating an ascetic way of life. However, other currents claimed that, being the salvation dependent only on the gnosis of the soul, the behavior of the body was irrelevant, apologizing it from all moral bondage and freeing it to all kinds of enjoyments. Other teachings reproduced the multiplication of matter, thus procreation a condemnable act. There were also currents that, like Plainism and Eastern philosophies, believed in the cyclical return of souls to the prison of matter through reincarnation. The initiate also sought to break this cycle through gnosis (through enlightenment, in the Eastern religions).

- Allegorical interpretation of Christianity and scriptures. Thus, the stories of creation are reinterpreted in the gnostic light, etc. giving them philosophical meanings.

- Establishment of spiritual hierarchies: At the top of beings there is a God, a perfect and immanent being whose own perfection makes it unrelated to the rest of imperfect beings. It's immutable and inaccessible. Descending on a scale of beings emanating from that we reach the Demiurgo, antithesis and culmination of the progressive degeneration of spiritual beings, and origin of evil. In their iniquity, the Demiurgo creates the world, matter, chaining the spiritual essence of men to the prison of the flesh. In this scenario a battle is waged between the principles of good and evil, matter (appearance) and spirit (substantiation). We can see clear parallels with Zoroastrianism.

- Establishment of human hierarchies: At the top of the human hierarchy were the initiates, in which the spirit is predominant. They can experience gnosis and thus access salvation. Below is the rest of the Christians, in which the sensitive soul predominates and can be saved following the guidance of the first. In the lower part are those in which the body predominates and therefore will not attain salvation.

Mystical and/or mythological concepts

Among the mystical concepts with mythological characteristics present in Gnosticism we can find:

- Arconte

- Demiurgo

- Monada

- Abraxas

- Eon

- Pléroma

History and sources

Three periods can be discerned in the development of Gnosticism:

- End of the centuryI and early centuriesII: development of Gnostic ideas, contemporary to the writing of the New Testament;

- mid-centuryII until the beginning of the centuryIII: summit of the classic gnostic masters and their systems, "who claimed that their systems represented the inner truth revealed by Jesus";

- end of the centuryII until the centuryIV: reaction of the proto-orthodox church and condemns as heresy, and later decline.

During the early period, three types of tradition developed:

- Genesis was reinterpreted in Jewish media, seeing Yahweh as a jealous God who enslaved people; freedom must be obtained from this jealous God;

- A sapiential tradition was developed, in which the sayings of Jesus were interpreted as indicators of esoteric wisdom, in which the soul could be divinized through identification with wisdom. Some of Jesus' sayings may have been incorporated into the gospels to limit this development. The conflicts described in 1 Corinthians may have been inspired by a clash between this sapiential tradition and the Pauline gospel of the crucifixion and the resurrection; It developed a mythical story about the descent of a heavenly creature to reveal the divine world as the true home of human beings. Jewish Christianity saw the Messiah, or Christ, as "an eternal aspect of God's hidden nature, his "spirit" and "truth," which was revealed throughout sacred history."

- A mythical story was developed about the descent of a heavenly creature to reveal the divine world as the true home of human beings. Jewish Christianity saw the Messiah, or Christ, as "an eternal aspect of God's hidden nature, his 'spirit' and 'truth', which was revealed throughout sacred history."

Some Christians identify Simon Magus, a character who appears in a narrative in the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament, as a Gnostic. His most relevant personality was Valentine of Alexandria, who brought an intellectualizing Gnostic doctrine to Rome. In Rome he had an active role in the public life of the Church. His prestige was such that he was considered as a possible bishop of Rome. Another renowned Gnostic is Paul of Samósata, author of a famous heresy on the nature of Christ. Carpocrates conceived the idea of the moral freedom of the perfect, in practice a total absence of moral rules.

Eventually, the wide range of moral variation in Gnosticism was viewed with suspicion, and Bishop Irenaeus of Lyons declared it a heresy in AD 180. C., for the Catholic Church.

The movement spread to areas controlled by the Roman Empire and the Arian Goths, and the Persian Empire. It continued to develop in the Mediterranean and Middle East before and during the 2nd and 3rd centuries, but declined also during the 3rd century, due to the growing dislike of the Nicene Church and the economic and cultural decline of the Roman Empire. Conversion to Islam and the Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229) greatly reduced the number of Gnostics remaining throughout the Middle Ages, although Mandaean communities still exist today in Iraq, Iran, and Diaspora communities. Gnostic and pseudo-gnostic ideas came to influence some of the philosophies of various 19th and 20th century esoteric mystical movements in Europe and North America, including some that explicitly identify themselves as revivals or even continuations of earlier Gnostic groups.

In 1945 a library of Gnostic manuscripts was discovered in Nag Hammadi (Egypt), which has allowed a better knowledge of their doctrines, previously only known through citations, refutations, apologies and heresiology made by Church Fathers.

Neognosticism

Modern gnosticism or neognosticism includes a variety of religious movements, derived from ancient Hellenistic society around the Mediterranean. In the 19th century popular studies were published that made use of recently rediscovered texts. In this period there was also reactivation of the Gnostic religious movement in France. The emergence of the Nag Hammadi library in 1945 significantly increased the number of available texts.

Original Gnosticism includes a variety of religious movements, mostly Christians, in ancient Hellenistic societies in the Mediterranean Sea. Although the origins are in dispute, most of these movements flourished approximately from the time of the foundation of Christianity (at the end of the 1st century) to the 4th century, when the writings and activities of groups considered heretics or pagans were actively repressed. For many centuries, the only available information about these movements was the criticism of those who wrote against those ideas, and the few quotations retained in those works.Relation to early Christianity

Dillon notes that Gnosticism raises questions about the development of early Christianity.

Orthodoxy and heresy

Christian heresiologists, especially Irenaeus, regarded Gnosticism as a Christian heresy. Modern scholars point out that early Christianity was diverse, and that Christian orthodoxy only took hold in the 4th century, when the The Roman Empire declined and Gnosticism lost its influence. Gnostics and Proto-Orthodox Christians shared certain terminology. At first, it was difficult to distinguish one from the other.

According to Walter Bauer, "heresies" may well have been the original form of Christianity in many regions. This theme was developed by Elaine Pagels, who argues that "the proto-orthodox church found itself in debates with Gnostic Christians." which helped them stabilize their own beliefs." According to Gilles Quispel, Catholicism arose as a response to Gnosticism, establishing safeguards in the form of the monarchical episcopate, the creed, and the canon of holy scriptures.

Historical Jesus

Gnostic movements may contain information about the historical Jesus, while some texts preserve sayings that show similarities to canonical sayings. Especially the Gospel of Thomas has a significant number of parallel sayings. However, one notable difference is that the canonical sayings focus on the end times, while the Thomas sayings focus on a kingdom of heaven that is already here, and not on a future event. According to Helmut Koester, this is because the Thomas's sayings are older, implying that in early forms of Christianity Jesus was regarded as a teacher of wisdom. An alternative hypothesis is that the Thomas authors wrote in the 17th century II, changing existing sayings and removing apocalyptic concerns. According to April DeConick, such a change came about when the end times did not come, and the tr The Thomistic addition was oriented towards a "new theology of mysticism" and a "theological commitment to a kingdom of heaven fully present here and now, in which its church had achieved the divine status of Adam and Eve before the Fall".

Juanian Literature

The prologue to the Gospel of John describes the Logos incarnate, the light that came to earth, in the person of Jesus. The Apocryphon of John contains a schematic of three descendants of the heavenly realm, the third being Jesus, just as in the Gospel of John. The similarities probably point to a relationship between Gnostic ideas and the Johannine community. According to Raymond E. Brown, the Gospel of John shows "the development of certain Gnostic ideas, especially Christ as heavenly revelator, the emphasis on light versus darkness." obscurity and anti-Jewish animosity." The Johannine material reveals debates about the Redeemer myth. The Johannine letters show that there were different interpretations of the Gospel account, and the Johannine imagery may have contributed to Gnostic ideas of the II about Jesus as redeemer who descended from heaven. According to DeConick, the Gospel of John shows a "system of transition from early Christianity to Gnostic beliefs in a God who transcends our world". According to DeConick, John may show a bifurcation of the idea of the Jewish God in the heavenly Father of Jesus and the father of the Jews, "the Father of the Devil" (most translations read "of [your] father the Devil"), which may have developed into the Gnostic idea of the Monad and Demiurge.

Paul and Gnosticism

Tertullian calls Paul "the apostle of heretics", because Paul's writings were attractive to Gnostics, and they were interpreted in a Gnostic way, while Jewish Christians found him straying from the Jewish roots of Christianity. In 1 Corinthians, Paul refers to some members of the church as "possessors of knowledge" (Greek: τὸν ἔχοντα γνῶσιν, ton ejonta gnosin). James Dunn states that, in some cases, Paul held views closer to Gnosticism than proto-orthodox Christianity.

According to Clement of Alexandria, Valentine's disciples said that Valentine was a student of a certain Theudas, who was a student of Paul, and Elaine Pagels points out that Paul's epistles were interpreted by Valentine in a gnostic way, and that Paul could considered a protognostic as well as a proto-Catholic. Many texts from Nag Hammadi, including, for example, the Paul's Prayer and the Coptic Apocalypse of Paul, consider Paul to be "the great apostle". The fact that he claimed to have received his gospel directly by revelation from God attracted the Gnostics, who claimed gnosis of the risen Christ. The Naasenes, Cainites, and Valentinians referred to Paul's epistles. Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy have explored this idea of Paul as a Gnostic teacher at length, although their premise that Jesus was invented by early Christians based on an alleged Greco-Roman mystery cult has been rejected by scholars.. However Well, his revelation was different from the Gnostic revelations.

Main moves

Judeo-Israelite Gnosticism

Although the Elcesaites and Mandaeans were found primarily in Mesopotamia in the early centuries CE, their origins appear to be in the Jordan Valley.

Elcesaitas

The Elcesaites were a Judeo-Christian baptismal sect that originated in Transjordan and was active between AD 100 and 400. Members of this sect performed frequent purification baptisms and had a Gnostic disposition. The sect is named after its leader Elkesai.

According to Joseph Lightfoot, Church Father Epiphanius (writing in the IV century AD) seems make a distinction between two main groups within the Essenes: "Of those who came before his time [Elxai (Elkesai), an Osean prophet] and during his time, the Oseans and the Nasrids".

Mandeism

Mandaeanism is a Gnostic, monotheistic, ethnic religion. The Mandaeans are an ethnoreligious group that speaks a dialect of Eastern Aramaic known as Mandaean. They are the only surviving Gnostics from antiquity. Their religion has been practiced primarily in and around the lower Karun, Euphrates, and Tigris, as well as in the rivers surrounding the Chat-el-Arab waterway, in part of southern Iraq and in Khuzestan province in Iran. Mandaeanism continues to be practiced in small numbers, in parts of southern Iraq and in the Iranian province of Khuzestan, and there are believed to be between 60,000 and 70,000 Mandaeans worldwide.

The name Mandaean comes from the Aramaic manda, meaning knowledge.John the Baptist is a key figure in the religion, as an emphasis on baptism is part of his fundamental beliefs. According to Nathaniel Deutsch, "Mandaean anthropogony echoes both rabbinic and Gnostic accounts". The Mandaeans venerate Adam, Abel, Seth, Enos, Noah, Shem, Aram, and especially John the Baptist. Significant amounts of the original Mandaean Holy Scriptures, written in Mandaean Aramaic, survive into the modern era. The most important holy book is known as the Ginza Rabba and has portions identified by some scholars as having been copied as early as the 2nd and 3rd centuries, while other scholars such as S. F. Dunlap place it in the I. There is also the Qolastā, or Canonical Prayer Book and the Mandeo Book of John (Sidra ḏ'Yahia) and other scriptures.

The Mandaeans believe that there is a constant battle or conflict between the forces of good and evil. The forces of good are represented by Nhura (light) and Maia Hayyi (living water) and those of evil by Hshuka (darkness) and Maia Tahmi (dead or rancid water). The two waters mix in all things to achieve a balance. The Mandaeans also believe in an afterlife or heaven called Alma d-Nhura (World of Light).

In Mandeism, the World of Light is ruled by a Supreme God, known as Hayyi Rabbi ("The Great Life" or "The Great Living God"). God is so big, vast and incomprehensible that no words can fully describe how awesome God is. It is believed that countless numbers of Utras (angels or guardians), manifested from light, surround and perform acts of worship to praise and honor God. They inhabit worlds separate from the world of light and some are commonly referred to as emanations and are beings subservient to the Supreme God, which is also known as "The First Life". The names of the Utras include Second, Third, and Fourth Life (i.e., Yōšamin, Abatur, and Ptahil).

The Lord of Darkness (Krun) is the ruler of the World of Darkness made up of dark waters that represent chaos. The main defender of the world of darkness is a giant monster, or dragon, by the name of Ur, and an evil ruler also inhabits the world of darkness, known as Ruha. The Mandaeans believe that these malevolent rulers created a demonic offspring who are considered to own the seven planets and twelve constellations of the zodiac.

According to Mandaean beliefs, the material world is a mixture of light and dark created by Ptahil, who plays the role of demiurge, with the help of dark powers, such as Ruha, the Seven, and the Twelve.Adam's body (believed to be the first human created by God in the Abrahamic tradition) was formed by these dark beings, but his soul (or mind) was a direct creation of the Light. Therefore, the Mandaeans believe that the human soul is capable of being saved because it originates from the World of Light. The soul, sometimes referred to as the "inner Adam" or Adam kasia, urgently needs to be rescued from darkness, in order to ascend to the heavenly realm of the World of Light. Baptisms are a central theme in the Mandeism, since they are believed to be necessary for the redemption of the soul. The Mandaeans do not carry out a single baptism, as in religions such as Christianity, but consider baptism as a ritual act capable of bringing the soul closer to salvation. For this reason, the Mandaeans are baptized repeatedly throughout their lives. John the Baptist is considered by the Mandaeans to have been a Nazarene Mandaean. John is considered their greatest and last teacher.

Samaritan Baptist Sects

According to Magris, the Samaritan Baptist sects were a branch of the followers of John the Baptist. One branch was in turn headed by Dositheus, Simon Magus, and Menander. In this environment the idea arose that the world was created by ignorant angels. Their baptismal ritual eliminated the consequences of sin and led to a regeneration by which natural death, caused by these angels, was overcome. The Samaritan leaders were seen as "the embodiment of God's power, spirit, or wisdom, and as the redeemers and revealers of 'true knowledge'".

Simonians focused on Simon Magus, the magician baptized by Philip and rebuked by Peter in Acts 8, who became the archetype of the false teacher in early Christianity. The attribution by Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and others of a connection between the schools of his time and the person in Acts 8 may be as legendary as the stories attributed to him in various apocryphal books. Justin Martyr identifies Menander of Antioch as a student of Simon Mago. According to Hippolytus, Simonianism is an earlier form of the Valentinian doctrine.

The Quqites were a group following a type of Samaritan and Iranian Gnosticism in the II century AD. C. in Erbil and in the vicinity of what is now northern Iraq. The sect was named after its founder Quq, known as "the potter." Quqite ideology arose in Edessa, Syria, in the 2nd century century. The Quqites emphasized the Hebrew Bible, introduced changes to the New Testament, associated twelve prophets with twelve apostles, and held that the latter corresponded to the same number of gospels. Their beliefs appear to have been eclectic, with elements of Judaism, Christianity, paganism, astrology, and Gnosticism.

Spanish edition

- García Bazán, Francisco (2003-2017). Eternal Gnosis. Anthology of Greek, Latin and Coptic texts. Complete work in three volumes. Madrid: Editorial Trotta.

Contenido relacionado

Muhammad

Mercury (mythology)

Vulgate