Glomerulonephritis

Glomerulonephritis is a disease that affects the structure and function of the glomerulus, although the other structures of the nephron may subsequently be affected. It is a kidney disease that can have various causes and clinical presentations and in which the portion of the kidneys that helps filter waste and fluids from the blood is damaged. The generic term glomerulonephritis (implying an immune or inflammatory pathogenesis) designates various kidney diseases, usually of a bilateral. Many of these diseases are characterized by inflammation of the glomeruli, or small blood vessels in the kidneys, hence their name, but not all have an inflammatory component.

Since this is not strictly a single disease, its presentation depends on the specific disease entity: it can present with hematuria, proteinuria, or both, or as a nephrotic syndrome, nephritic syndrome, acute kidney injury, or acute kidney disease. chronic kidney disease.

Classification

Glomerulonephritis can be primary or secondary. Primary glomerulonephritis is referred to when renal involvement is not the result of a more general disease and clinical manifestations are limited to the kidney, and secondary glomerulonephritis when the condition is the result of a systemic disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus, diabetes, etc.) or an infection. Primary glomerulonephritis includes IgA or IgM nephropathy, mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis, and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Regarding secondary glomerulonephritis, they can be the consequence of a bacterial, viral or parasitic infection or of multisystemic diseases.

In summary, the primary causes are intrinsic, that is, intrarenal, and the secondary ones are extrinsic and are associated with infections (caused by bacteria, viruses, or parasites), with certain drugs, or with systemic disorders (eg, lupus, vasculitis or diabetes).

Some authorsdivide glomerulonephritis according to its pathological pattern and group it into two broad categories, namely, proliferative type and non-proliferative type. The proliferative type (that is, those characterized by an increase in the number of some glomerular cells) include IgA mesangial glomerulonephritis and IgM mesangial glomerulonephritis, membranoproliferative or mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis, poststreptococcal or diffuse endocapillary glomerulonephritis, and extracapillary glomerulonephritis.. In turn, those of the non-proliferative type (that is, without an increase in the number of cells in the glomeruli) include minimal change nephropathy, focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis, and membranous or extramembranous glomerulonephritis. Determining the histologic pattern of glomerulonephritis is important because prognosis and treatment differ by type.

As primary glomerulonephritis are highly heterogeneous entities both in terms of their etiology and their evolution, it is not possible to establish a single classification that allows them to be differentiated into homogeneous groups. However, if the evolutionary, histological and clinical data are considered, they can be classified into various types. For example, according to its evolution, glomerulonephritis can be acute (a form that begins at a known moment, usually with clear symptoms, and which usually presents with hematuria, sometimes proteinuria, edema, arterial hypertension and renal failure), subacute (of less clear onset, with a deterioration of renal function that progresses in weeks or months and shows no tendency to improve) and chronic (regardless of the beginning it tends to be chronic, it usually presents with hematuria, proteinuria, arterial hypertension and renal failure and evolves in a variable over the years, but tends to progress once damage sets in).

They can also be classified according to histology, which is the most widely used classification and provides useful information for prognosis. The different glomerular diseases can share clinical manifestations, which makes diagnosis difficult and explains the decisive role played by biopsy. Renal biopsy makes it possible to establish the correct diagnosis to administer a specific treatment and also makes it possible to detect acute or chronic lesions whose nature may not be suggested by the clinical history. This is important because discovery of more chronic and potentially irreversible lesions would prevent treatment of lesions unlikely to respond.

Lastly, according to the behavior of the complement, glomerulonephritis can be classified into those with normal serum complement and those with reduced complement (either in the C3 fraction, in the C4 fraction or in both). Those that present with a normal complement are minimal change disease, focal segmental glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy, primary membranous glomerulonephritis, and diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Those associated with hypocomplementemia include poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (low C3), lupus glomerulonephritis (low C3 and C4), membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis types I, II, and III (low C3), and glomerulonephritis associated with cryoglobulinemia(low C4 level).

History

Richard Bright, an English physician who made many contributions to medicine, including descriptions of diseases of the nervous system, pancreas, liver, and especially the kidney, published his greatest contribution to the field of renal pathology in 1827, the description of glomerulonephritis, a term coined by Edwin Klebs in 1875 and used as a synonym for "Bright's disease" since F. Volhard and T. Fahr introduced it in their classification of kidney diseases in 1914. Bright was the first to link the simultaneous presence of albuminuria, dropsy and lesion of the renal parenchyma and thus identified a new type of disease, in which he combined clinical signs with chemical alterations and structural changes. Bright associated clinical observation with laboratory tests in which the chemistry of the urine was analyzed and, finally, the necropsy made it possible to demonstrate the structural alterations of the kidney. This was the anatomoclinical criterion that this researcher led to a new scenario, that of renal pathology.

In his self-illustrated work entitled Reports of Medical Cases, Bright described observations made in patients who had developed edema and albuminuria after suffering from scarlet fever.

Epidemiology

According to the Spanish Glomerulonephritis Registry, with data obtained from 21,988 kidney biopsies performed during the period 1994-2013 (not including transplant biopsies), IgA nephropathy continues to be the most frequent pathology in kidney biopsies in that country. The male-female ratio is 3:1. In adults, the most frequent presentation is as persistent urinary abnormalities, but in those older than 65 years it presents more often with acute renal dysfunction. Nephrotic syndrome develops in thirteen percent of cases, but more frequently in people over 65 years of age.

There is a progressive increase in the age of patients undergoing renal biopsy and nephrotic syndrome is the most common cause. The most frequently observed pathologies are IgA nephropathy and systemic lupus erythematosus in adults and vasculitis and membranous nephropathy in those over 65 years of age. Acute renal dysfunction is increasing in frequency as a cause of renal biopsy, especially in those over 65 years of age, and is mainly associated with vasculitis and acute tubulointerstitial nephritis. The frequency of this last disease is increasing, especially in people over 65 years of age.

Etiology

Primary glomerulonephritis are immune-based diseases, although in most cases the antigen or ultimate cause of the condition is unknown. Immunity plays a fundamental role in triggering many types of glomerular lesions. In some cases, nonspecific activation of inflammation can cause or aggravate glomerular injury. Infectious microorganisms can also trigger abnormal immune responses or responses against microbial antigens. Lastly, genetic factors can be the cause of glomerular nephropathy, but they can also influence the predisposition to the development of glomerular lesions, the progression of that lesion, or the response to treatment.

Pathogenesis

Glomerulonephritis is a disease characterized by intraglomerular inflammation and cell proliferation associated with hematuria, in whose pathogenesis both cellular and humoral immune mechanisms play an important role. The complement system is also important. Its activation is associated with characteristic patterns of decreased serum concentrations, some of which are practically diagnostic of certain nephritis. The pathogenesis, then, can be immune or inflammatory, with the participation of cells and mediators of the immune system, including the complement pathway. Intrinsic glomerular cells, particularly podocytes, are important in and response to glomerular injury.

Pathology

Histological classification

As already stated, glomerulonephritis can have an immune or inflammatory pathogenesis and although in some situations it is possible to establish a specific diagnosis based on clinical presentation and laboratory tests, in most cases it is useful perform a renal biopsy both for classification and to determine prognosis. In addition, biopsy specimens should ideally be examined under light microscopy, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy because such an approach will allow diagnosis of the histologic pattern. In some cases that pattern can be compared with the results of other laboratory tests to identify a specific etiology, but in many others the disease is idiopathic. Still, because treatments are often developed for specific histologic patterns, this approach is preferred in the current management of these disorders.

Histopathology

Full histopathological evaluation of samples obtained for renal biopsy requires the use of light and electron microscopy and examination with immunofluorescence or immunoperoxidase techniques to detect complement and immunoglobulin deposits.

Optical microscopy

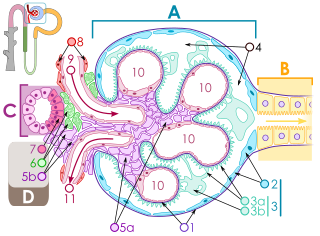

In glomerulonephritis, the dominant histological lesions in light microscopy, although not the only ones, are located in the glomeruli. The disease is described as focal (only affects some glomeruli) or diffuse. In any individual glomerulus the lesion can be segmental (affecting only part of the glomerulus) or global. In summary, glomerular lesions can be focal (only present in some glomeruli) or diffuse (present in all or almost all glomeruli) and segmental (involve only part of the glomerulus) or global (involvement of the entire glomerulus). Obtaining samples for kidney biopsy can make mistakes. For example, if the sample is small, the extent of a focal lesion may be misjudged and cross sections may miss segmental lesions. Lesions may also be hypercellular due to an increase in endogenous endothelial or mesangial cells (in which case they are called proliferative) or infiltration of inflammatory leukocytes (in this case they are called exudative). When the inflammation is acute and intense it can cause glomerular necrosis, which is often segmental. In addition, thinning of the glomerular capillary walls may occur due to various processes, including increased immune deposits in the glomerular basement membrane. There may also be sclerosis and the formation of segmental scars, which are characterized by segmental capillary collapse with accumulation of hyaline material and mesangial matrix and many times fixation of the capillary wall to Bowman's capsule (which determines the formation of synechiae or adhesions).

The classic stains used in light microscopy are hematoxylin-eosin and the periodic acid-Schiff reaction, which is particularly useful for assessing cellularity and matrix expansion. More specific stains include the silver stain, which stains the glomerular basement membrane black and may reveal, among other things, a double contour of the membrane due to interposition of cellular material or increased mesangial matrix that would not easily detect with other techniques. Trichrome staining is also useful for detecting areas of scarring (staining blue) while immune deposits stain red. Crescents, which are inflammatory collections of cells present in Bowman's space, develop when there is severe glomerular injury that results in local rupture of the capillary wall or Bowman's capsule, allowing the ingress of plasma proteins and inflammatory material in the homonymous space. The crescents are composed of proliferating epithelial and parietal cells, infiltrative fibroblasts, and also lymphocytes and monocyte-macrophages, often with local fibrin deposits. They are called crescents because of the appearance they present when cut in a plane of the glomerulus to study its histology. They are destructive and their rapid increase in size leads to occlusion of the glomerular networks. If the acute lesion ceases, the crescents may resolve with restoration of normal morphology or heal with fibrosis and cause irreversible loss of renal function. Crescents are more frequent in cases of vasculitis, in Goodpasture's disease, and in severe acute forms of glomerulonephritis of any etiology. Tubulointerstitial injury and fibrosis may also be present in glomerulonephritis, possibly playing an important role in prognosis.

Immunofluorescence and Immunoperoxidase Techniques

Indirect immunofluorescence and immunoperoxidase staining are used to identify immune reactive phenomena. The stain is used to detect IgG, IgA, and IgM, components of the complement system (usually C3, C4, and Clq), and fibrin, which is commonly seen in crescents and capillaries in thrombotic disorders (such as HUS and HUS). antiphospholipid syndrome). Immune deposits may be present along capillary loops or in the mesangium and may be continuous (linear) or discontinuous (granular).

Clinical picture

Common symptoms in patients with glomerulonephritis include hematuria, proteinuria, and facial swelling, eyelid swelling, and swelling of the ankles, feet, legs, or abdomen. Other possible symptoms are abdominal pain, hematemesis, melena, cough, dyspnea, diarrhea, polyuria, fever, malaise, fatigue, anorexia, arthralgia, and epistaxis. If the disease is chronic, the patient may develop symptoms over time.

Diagnosis

Glomerulonephritis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality and a potentially preventable cause of end-stage renal disease so early diagnosis is vital to allow timely referral of patients to specialized renal biopsy units.

The filtration function performed by the glomerular structures not only involves the elimination of water but also the selective elimination of substances present in the blood. Any alteration that occurs in these anatomical and physiological structures will lead to anomalies in the filtration work they perform. Given that proteinuria and hematuria are typical findings, in the first clinical evaluation it will be necessary to determine if there is proteinuria and, if so, what is its magnitude, the presence of associated hematuria, the development of renal failure and the existence or not of arterial hypertension.

The best method for diagnosing renal diseases of immune etiology consists of performing a renal biopsy and studying the stained tissues with light microscopy because in this way it will be possible to anticipate the prognosis and select the appropriate treatment. However, as there are several immune mechanisms that can cause similar morphological changes, immunofluorescence microscopy with specific fluorescein-labeled antibodies is also useful to determine the type and localization of immune compounds in the kidney. In addition, renal biopsy is important because it not only allows us to know where the histological lesion is located or what mechanisms are involved, but also the degree of importance of said lesion, a fundamental factor in deciding what type of therapeutic management is required and when to start it.

Clinical criteria can be used, but the diagnosis requires histologic confirmation with one exception, namely childhood minimal change disease. In this case, a positive response to steroid treatment is considered diagnostic.

In antibody-mediated renal disease (anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies, anti-HLA antibodies) serologic testing can detect circulating cytotoxic antibodies and in Wegener's granulomatosis (a nephropathy mediated by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies or ANCA) they can find circulating ANCA.

Abnormalities in the level of complement proteins can generally distinguish between types of immune-mediated nephropathy. When activation via the alternative pathway predominates (as occurs in membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis and frequently in post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis), complement consumption begins with C3 activation, so the first complement elements (C1q, C4, and C2) are not downregulated. When the classical route is activated (as in systemic lupus erythematosus), consumption begins in the first components, which will therefore be decreased. The presence of nephritic factor C3 with low levels of C3 and normal levels of C1q, C4 and C2 is practically diagnostic of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis due to activation of the alternative pathway.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of glomerulonephritis without systemic disease includes poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, and membanoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Glomerular inflammation is probably induced directly by a nephritogenic streptococcal protein in poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and by mesangial deposition of abnormally glycosylated IgA1-containing immune aggregates in IgA nephropathy. In rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis with crescent formation, it is increasingly clear that cellular rather than humoral immune mechanisms are involved. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection exists in many patients with membanoproliferative glomerulonephritis.

Treatment

Treatment varies depending on the pathogenesis. Several therapeutic alternatives have been developed, but many of these diseases remain resistant to all treatments. For example, there is no effective specific therapy for poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis or IgA nephropathy. General measures and treatment are usually applied to alleviate the symptoms. If there is active infection, the corresponding antibiotic therapy is indicated. Patients with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis benefit from high-dose steroids and cytotoxic drug therapy plus the addition of plasmapheresis in disease induced by antibodies against the glomerular basement membrane. Antiviral treatments reduce the severity of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis due to hepatitis C virus. New forms of treatment directed against specific cytokines, growth factors, fibrin deposition and other mediators of injury are being developed to find effective therapeutics as well as more specific and less toxic forms of immunotherapy.

Principles of new treatments include modulation of the host's immune mechanisms to eliminate antigen, antibody, or immune complexes, induction of immunosuppression by immunosuppressive drugs, and administration of anti-inflammatory agents and, in some cases, of anticoagulant and platelet inhibitor drugs. If eradication of the antigen is not achieved, the antigenic load must be reduced and an excess of antibodies created to favor the elimination of the immune complexes by the normal mononuclear phagocytic system. Plasma exchange is beneficial in anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. Other than lupus and perhaps also membranous glomerulonephritis, few diseases respond to the administration of daily or large-dose steroids. In Wegener's granulomatosis and perhaps also in membranous glomerulonephritis and lupus the drug of choice is cyclophosphamide. For type I membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, the only recommended treatment is the administration of platelet inhibitors (dipyridamole, aspirin, and ticlopidine). Cytotoxic antibody levels are difficult to reduce in type II membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis because of the persistence of the stimulatory antigen.

One of the first goals of treatment is to control blood pressure, which can be very difficult if the kidneys are malfunctioning. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (eg, captopril) or angiotensin-converting enzyme receptor antagonists (eg, losartan) are prescribed when hypertension is present. To reduce the inflammation triggered by the immune response, corticosteroids are indicated and if they do not work, plasmapheresis can be used (with which part of the plasma is removed and replaced by intravenous fluids or donor plasma -without antibodies-).

In the chronic form of the disease, it is necessary to reduce the intake of protein, salt and potassium from the diet. Calcium supplements may be indicated and diuretics may be required to reduce edema.

If the disease progresses anyway and the patient develops kidney failure, dialysis will be necessary.

Forecast

Glomerulonephritis can be a temporary and reversible disease or it can get worse. Progressive glomerulonephritis may lead to chronic renal failure, impaired renal function, or end-stage renal disease. If nephrotic syndrome is present and can be controlled, other symptoms may also be controlled. On the other hand, if it cannot be controlled, the possible result is end-stage renal disease.

Contenido relacionado

Dissociative drug

Lymph node

Proprioception