Giraffa camelopardalis

The giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) is a species of artiodactyl mammal of the Giraffidae family native to Africa. It is the tallest of all existing terrestrial animal species, as it can reach a height of 5.8 m and a weight that varies between 750 and 1,600 kg.

They are uniquely adapted to reach vegetation inaccessible to other herbivores. Their unusually elastic blood vessels and specially adapted valves help compensate for the sudden pooling of blood (to prevent fainting, clearly) when the giraffes' heads are raised, lowered or swung rapidly.

Its range is scattered, stretching from Chad in Central Africa to South Africa in the south, and from Niger in the west to Somalia in the east. It generally inhabits savannahs, grasslands, and open woodlands. It feeds mainly on acacia leaves, which it browses at heights inaccessible to most other herbivores. Adult giraffes are preyed on by lions, and giraffe calves also by leopards, spotted hyenas, and wild dogs. Adult giraffes do not have strong social bonds, although they do group together in loose, open herds without actually moving in the same general direction. The males establish a social hierarchy, through duels known as "necking", a combat in which they use the neck and head as a weapon. Only dominant males can mate with females; only females are dedicated to raising calves.

The common name «giraffe» and first term of the binomial name Giraffa comes from the Arabic الزرافة (ziraafa or zurapha), which means « high". The second term that gives its name to the species camelopardalis comes from the Greek καμηλοπάρδαλη camelopardalis and from the Latin camelopardalis, meaning "leopard camel".

Julius Caesar introduced the first giraffe to Europe from his campaigns in Asia Minor and Egypt, where he met Cleopatra. Not knowing what animal it was, the Romans baptized it cameleopardo, a cross between a camel and a leopard, becoming the scientific name used to this day.

Because of its peculiar appearance, the giraffe was a source of fascination in various cultures, both ancient and modern, appearing frequently in paintings, books and cartoons. In 2016, the IUCN downgraded it from Least Concern to Vulnerable, observing a population decline of up to 40% in the period 1985-2015. However, there are still large numbers of giraffes in national parks and game reserves.

Etymology

The name "giraffe" has its earliest known origins in the Arabic word zarafa (زرافة), and possibly in some African language. The name translates as "fast walker". The Arabic word was possibly derived from geri, the Somali name for the animal. The Italian form, giraffa, arose in the 1590s. There were several different spellings in English. Middle, such as jarraf, ziraph, and gerfauntz. The Modern English form, giraffe, developed around 1600 from the French girafe. The specific name of the species, camelopardalis, comes from the Latin.

Other African names for the giraffe include Kameelperd (Afrikaans), ekorii (Ateso), kanyiet (elgon), nduida (gikuyu), tiga (kalenjin and luo), ndwiya (kamba), nudululu (kihehe), ntegha (kinyaturu), ondere (lugbara), etiika (luhya), kuri (ma'di), oloodo-kirragata or olchangito-oodo (Maasai), lenywa (meru), hori (pare), lment (Samburu) and twiga (Swahili and others) in the east; and Tutwa (Lozi), nthutlwa (shangaan), indlulamitsi (siswati), thutlwa (sessoto), thuda (venda) and ndlulamithi (zulu) in the south.

Taxonomy and evolution

The giraffe belongs to the suborder Ruminantia, and many Ruminantia have been described since the mid-Eocene in Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and North America. Ecological conditions during this period may have facilitated their rapid dispersal. Along with the okapi, the giraffe is one of two extant species in the family Giraffidae. Previously, the family was much broader, since it has more than ten described fossil genera. Its closest known relatives are the now extinct climacoceratids. These, together with the family Antilocapridae (whose only extant species is the pronghorn), belong to the superfamily Giraffoidea. These animals evolved during the Miocene from the extinct family Palaeomerycidae in south-central Europe, eight million years ago.

Although some ancient giraffids, such as Sivatherium, had massive, compact bodies, others, such as Giraffokeryx, Palaeotragus—the possible ancestor of the okapi —, Samotherium, and Bohlinia were more elongated. Bohlinia penetrated China and northern India in response to climate change. From there evolved the genus Giraffa, which entered Africa approximately seven million years ago. Other climatic changes caused the giraffes of Asia to go extinct, while the giraffes of Africa survived, developing into several new species. G. camelopardalis arose about 1 Ma in eastern Africa during the Pleistocene. Some biologists suggest that the modern giraffe is descended from G. jumae; others maintain that G. gracilis is a more likely candidate. The main driver of giraffe evolution is thought to have been the transformation of extensive forests to more open habitats, a process that began 8 Ma ago. Some researchers hypothesized that that the new habitat brought a different diet, including Acacia leaves, which may have exposed the giraffe's ancestors to toxins that caused high mutation rates and a faster rate of evolution.

The giraffe was first described in 1758 by Charles Linnaeus, who gave it the binomial name Cervus camelopardalis. Morten Thrane Brünnich classified the genus Giraffa in 1772. In the 19th century, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck suggested that the giraffe's long neck is an "acquired characteristic", developed when generations of ancestral giraffes struggled to reach the leaves of tall trees. This theory was ultimately rejected, and scientists now believe that the giraffe's neck it was elongated by Darwinian natural selection, meaning that ancestral giraffes with long necks had a competitive advantage that allowed them to reproduce better and pass on their genes more successfully.

Subspecies

As of 2016, they recognized up to nine subspecies. An analysis of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA showed "clearly" that giraffes do not belong to a single species, but to four different species. The species and their subspecies, considering the most recent genetic study, would be the following (with population estimates dating from 2010):

- Giraffa camelopardalis

- The Nubian giraffe, G. c. camelopardalis, is the nominal subspecies located in the east of South Sudan and south-west of Ethiopia. It is believed that less than 250 specimens live in a wild state, although this number is uncertain. It is rare in captivity, although there is a group at the Al Ain Zoo in the United Arab Emirates. In 2003, this group had 14 members.

- The giraffe of Kordofan, G. c. antiquorumIt has a distribution that includes southern Chad, northern Cameroon, Central African Republic, and north-east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Previously, the populations of Cameroon were included in G. c. peraltaBut this was wrong. It is estimated that this subspecies has a population of less than 3000 in a wild state. There was considerable confusion between this subspecies and G. c. peralta regarding the number in captivity in zoos. In 2007, it was found that all alleged G. c. peralta in European zoos, they were actually G. c. antiquorum. Taking this correction into account, about 65 are kept in zoos.

- The giraffe of West Africa, G. c. peraltaalso known as Niger giraffe or Nigerian giraffe, is endemic to the southwest of Niger. Less than 220 specimens remain wild. Previously it was believed that the giraffes of northern Cameroon belonged to this subspecies, but it was found that they actually belong to G. c. antiquorum. This error led to some confusion about their status in zoos, but in 2007, it was established that all “G. c. Peralta» in European zoos are actually G. c. antiquorum.

- Rothschild's giraffe, G. c. rothschildiwhich bears the name of Walter Rothschild, is also known as Baringo or Ugandan giraffe and its distribution area includes parts of Uganda and Kenya. Its presence in southern Sudan is uncertain. It is estimated that less than 700 remain in the wild, and more than 450 are in captivity in zoos.

- Giraffa reticulata

- The reticulated giraffe, G. r. reticulata, also known as the giraffe Somalia, is native to north-east Kenya, south of Ethiopia, and Somalia. It is estimated that less than 5,000 remain in the wild, and according to the records of the International Species Information System, more than 450 are in zoos.

- Giraffa tippelskirchi

- The giraffe Masai, G. t. tippelskirchi, also known as the giraffe of the Kilimanjaro, inhabits the center and south of Kenya and Tanzania. It is estimated that less than 40 000 remain in a wild state, and about 100 are kept in zoos.

- The giraffe of Zambia, G. t. thornicrofti, also known as Thornicroft giraffe named in honor of Harry Scott Thornicroft, is limited to the Luangwa valley in eastern Zambia. It is estimated that less than 1500 remain in a wild state, and none in zoos.

- Giraffa Giraffa

- The giraffe of South Africa, G. g. GiraffaIt is located in northern South Africa, southern Botswana, southern Zimbabwe, and south-west Mozambique. It is estimated that less than 12,000 remain in the wild, and about 45 remain in zoos.

- The giraffe of Angola or giraffe of Namibia, G. g. angolensisIt is located in northern Namibia, southwest of Zambia, Botswana, and western Zimbabwe. A 2009 genetic study of this subspecies indicates that populations in the north of the Namib desert and Etosha National Park are a different subspecies. It is estimated that less than 20 000 specimens remain in a wild state; and about 20 are found in zoos.

Giraffe subspecies are distinguished by their fur patterns. The reticulated giraffe and the Maasai giraffe represent two extremes by the shape of the spots on their fur. The former has rounded-shaped spots, while the latter has jagged ones. The width of the lines separating the spots differs as well. The West African giraffe has thick lines, while the reticulated and Nubian giraffe have thinner lines. The West African giraffe also has lighter fur than the other subspecies.

A 2007 study of the genetics of six subspecies—the West African, Rothschild, reticulated, Maasai, Angola, and South African giraffes—already suggested they may be separate species rather than subspecies. Based on genetic drift in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), the study deduces that giraffes in these populations are in reproductive isolation and do not often interbreed, despite no natural barriers to access between populations. This includes adjacent populations of Rothschild, Reticulated, and Maasai giraffes. The Masai giraffe may also consist of a few species separated by the Great Rift Valley. Reticulated and Maasai giraffes have the highest mitochondrial DNA diversity, which is consistent with the fact that giraffes originated in eastern Africa. The northernmost populations evolved from the former, while the southernmost populations evolved from the latter. Giraffes appear to choose mates with the same coat type, which is defined as calves. The implications of these findings for giraffe conservation were summarized by David Brown, the study's lead author, who told the BBC that "Lumping all giraffes into one species hides the reality that some types of giraffe are on the brink [of extinction]. Some of these populations only number a few hundred animals and need immediate protection."

According to that study, the West African giraffe is more closely related to Rothchild's and reticulated giraffes than it is to the Kordofan giraffe. Their ancestors may have migrated from the east into North Africa and then into their present range due to the development of the Sahara desert. During the Holocene, Lake Chad, at its most extensive, may have acted as a natural barrier between Kordofan and West African giraffes.

Anatomy and morphology

Adult giraffes can reach a height of 5–6 m; adult males are larger than females. The adult male has an average weight of 1,192 kg, and the female averages 828 kg. Despite its long neck and long legs, the body is relatively short. His eyes, located on either side of his head, are large and bulging, giving him good all-round vision from his great height. He can distinguish colours, and his senses of hearing and smell are also keen. For protection against sandstorms and ants, it can close its muscular nostrils. It has a prehensile tongue that is about 50 cm long. It is purple-black in color, possibly to protect against sunburn, and is used for grasping foliage, as well as for grooming and cleaning the animal's nose. The upper lip is also prehensile and is used during harvesting. of foliage. The lips, the tongue and the inside of the mouth are covered with papillae that provide protection against the spines.

The coat has dark patches or spots—which can be orange, chestnut, brown, or nearly black—separated by light hair, usually white or cream in color. Males become darker as they age. The pattern of the coat serves as camouflage, as it blends in with the light and shadow patterns of savannah forests. The skin beneath the dark patches are sites for complex systems of blood vessels and large sweat glands, and can serve as windows for thermoregulation. A giraffe's skin is mostly gray. It is also thick and allows it to move through thorn-brush forests without injury. The fur can serve as a chemical defense, as the parasite repellants it contains They give the animal a characteristic odor. Fur contains at least 11 scent chemicals, although indole and 3-methylindole are responsible for most of the odor. As males have a stronger scent than females, it is possible that scent also has a sexual function. Along the neck it has a mane of short, erect hairs. The tail is one meter long and ends in a long tuft. dark hair that serves as a defense against insects.

Skull and Osicones

Both sexes have ossicones, prominent horn-like structures; they are formed from ossified cartilage, and are covered in skin and fused to the skull at the parietal bones. Because they are vascularized, ossicones may have some role in thermoregulation, and are also used in dueling between males. The appearance of the ossicona allows distinguishing the sex or age of a giraffe: the ossicona of females and juveniles are slender and have a small tuft of hair on top, while the ossicona of adult males end in knobs. and tend to be bald on top. A median bump, more pronounced in males, emerges from the front of the skull. Males develop calcium deposits that form bumps on the skull as they age. multiple cranial sinuses resulting in a lighter skull. However, the skulls of males become heavier and more golf club-like as they age, helping them to be more d dominant in combat. The upper jaw has a grooved palate and lacks front teeth. The molars have a rough surface.

Legs, locomotion and posture

A giraffe's front and rear legs are about the same length. The radius and ulna of the forelegs are articulated by the carpus which functions like a knee, although it is structurally equivalent to the human wrist. The foot has a diameter of 30 cm, and the hoof is 15 cm high in males and 10 cm in females. The rear of the hooves is low and the spurs are close to the ground, allowing the foot to support the weight of the animal. It lacks interdigital glands. The pelvis, although relatively short, has an extended ilium at the upper ends.

He only has two gaits: walking and galloping. Walking is done by moving the legs simultaneously on one side of the body, and then doing the same on the other side. At a gallop, the hind legs move around the front legs before the latter move forward, and the front legs are held. tail tucked. While galloping, it relies on forward and backward movements of the head and neck to maintain balance and counter momentum. It can reach a top speed of up to 60 km/h over short distances, and it can sustain a speed of 50 km/h over a distance of several kilometres.

It rests by lying down with its body on top of its bent legs. To lie down, it kneels on its front legs, then lowers the rest of its body down. To stand up, it first kneels and extends its hind legs to raise its hindquarters. Finally it straightens its front legs. It sways its head with each step. In captivity it sleeps intermittently for about 4.6 hours per day, mainly at night. It usually sleeps lying down, although standing sleeps have been reported, particularly among elderly giraffes.. When lying down, it has brief intermittent phases of "deep sleep", characterized by bending the neck back to rest the head on the hip or thigh, a position believed to indicate paradoxical sleep. If the giraffe wills stoop to drink, either spread their front legs laterally, or bend their knees. Giraffes would probably not be good swimmers because their long legs would be very cumbersome in the water, although they may be able to float. When swimming, the thorax it would be weighed down by the weight of the front legs, making it difficult for the animal to move its neck and legs in harmony or keep its head above the surface of the water.

Neck

The giraffe has a highly elongated neck that can reach up to 2 m in length and accounts for most of the animal's vertical height. The length of the neck is the result of disproportionate elongation of the cervical vertebrae, and not it is due to extra vertebrae. Each cervical vertebra has a length of more than 28 cm. They represent 52-54% of the length of the giraffe's vertebral column; by comparison, 27-33% is typical of similar large ungulates, including the giraffe's closest living relative, the okapi. Neck elongation occurs mainly after birth, as females would have difficulty giving birth to calves with the same neck proportions as adult giraffes. The head and neck are supported by a nuchal ligament and large muscles that are anchored by long dorsal spines on the anterior thoracic vertebra, giving the animal a hump.

The neck vertebrae have ball-and-socket joints. The atlas–axis joint (C1 and C2) in particular allows the giraffe to tilt its head vertically to reach the highest branches with its tongue. The point of articulation between the vertebrae The cervical and thoracic vertebrae of giraffes have been displaced to the first and second thoracic vertebrae (T1 and T2), unlike most other ruminants, where the articulation is between the seventh cervical vertebra (C7) and T1. This allows C7 to directly contribute to the increase in neck length and has led to the suggestion that T1 is really C8, and that giraffes added an extra cervical vertebra. However, this proposition is not generally accepted, since T1 has other morphological features, such as a rib joint, considered diagnostic of thoracic vertebrae, and because exceptions to the limit of seven cervical vertebrae among mammals are often ca be characterized by an increase in neurological abnormalities and disease.

There are two main hypotheses about the evolutionary origin and conservation of giraffe neck elongation. The "browser competition hypothesis" was originally suggested by Charles Darwin, and has only recently been challenged. This hypothesis suggests that competitive pressure among smaller browsers, such as kudu, steenbok, and impala, encouraged giraffe neck elongation, as it allowed access to food beyond the reach of competing species. This advantage is real, considering that giraffes feed on foliage to a height of 4.5 m, while larger competitors such as kudu only manage to browse to a height of 2 m. There is also research suggesting that there is intense competition among browsers at lower levels, and that giraffes forage more efficiently—gaining more leaf biomass with each bite—when they forage high in the canopy. However, scientists do not agree that giraffes spend time feeding at levels beyond the reach of other browsers, and a 2010 study found that adult giraffes with longer necks even suffered higher mortality rates during droughts than their counterparts with shorter necks. This study suggests that maintaining a longer neck requires more nutrients, putting long-necked giraffes at risk during a period of food shortage.

The second major theory, the sexual selection hypothesis, proposes that long necks evolved as a secondary sexual characteristic, conferring an advantage to males during necking combat. /i>, see below—by which dominance is established between rival males, allowing access to sexually receptive females. The fact that the necks are longer and heavier in males than in females of the same age, and that males do not use other forms of combat, seems to support this theory. One objection, however, is that the theory does not explain why females also have long necks.

The Giraffidae family only has two species; Due to the characteristic long neck of the giraffe, genomic studies have tried to explain this particularity in giraffes. By obtaining the sequence of the two members of this family and through comparative analysis with other eutherian mammals, 70 genes that present multiple signs of giraffe adaptation were identified. These genes encode regulators of bone, cardiovascular, and nervous development.

In another study, the sequences of the two species of the Giraffidae family were aligned with those of cattle (Bos taurus). The result was that the giraffe's long neck is likely the result of mutations in two sets of genes, one of those groups controlling gene expression patterns during neck development, and the other group controlling the expression of growth factors.

In turn, a number of genes related to the evolution of a more powerful cardiovascular system were also linked to deal with the problem of a longer neck that also requires the passage of blood. This is why the giraffe has some of the most difficult physiological problems. But such adaptations or solutions of nature, especially in relation to its circulatory system, can be useful for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases and hypertension in humans.

Internal systems

In mammals, the left recurrent laryngeal nerve is longer than the right; in the giraffe it is more than 30 cm longer. These nerves are longer in the giraffe than in any other living animal; the left nerve has a length of more than 2 m. Each nerve cell in this conduction begins in the brain stem and passes through the neck along the vagus nerve, and then branches into the recurrent laryngeal nerve which passes back through the neck to the larynx. Therefore, these nerve cells have a length of almost 5 m in the largest giraffes. The structure of a giraffe's brain resembles that of domestic cattle. The skeletal shape only allows for a relatively small lung volume. with its mass. Its long neck gives it a large volume of dead space, despite its narrow trachea. These factors increase resistance to airflow. However, the animal can supply enough oxygen to its tissues.

The giraffe's circulatory system has several adaptations for its great height. Your heart, which can weigh more than 25 pounds and is about 24 inches long, must generate about twice the blood pressure required for a human to maintain blood flow to your brain. Therefore, the wall of the heart can be as thick as 7.5 cm. At 150 beats per minute, the giraffe has an unusually high heart rate for its size. The pressure, known as rete mirabile, prevents excess blood flow to the brain when the giraffe lowers its head. The jugular veins also contain several valves (usually seven) to prevent blood from flowing to the head from the vein. inferior vena cava and right auricle, when the giraffe lowers its head. Instead, the blood vessels in the lower legs are under great pressure (due to the weight of the fluid that is pressing down). To solve this overpressure problem, the skin of the lower extremities is thick and tight; this adaptation prevents excess blood in the paws.

The giraffe has unusually strong esophageal muscles to be able to regurgitate food from the stomach up to the neck and into the mouth for rumination. Like other ruminants, it has a four-chambered stomach, the first chamber of which is adapted to its diet. specialized. Giraffe intestines are 80 m long and the ratio of small to large intestine is relatively small. The liver is small and compact. A gallbladder is usually present during fetal life, but may disappear before birth.

Behavior and ecology

Habitat and feeding

Giraffes generally inhabit savannahs, grasslands, and open woodlands. They prefer open forests of Acacia, Commiphora, Combretum and Terminalia over denser environments, such as forests of Brachystegia. The Angolan giraffe usually inhabits desert environments. It browses the branches of trees, with a preference for trees of the genera Acacia, Commiphora , and Terminalia, which are important sources of calcium and protein necessary for the giraffe's growth rate. It also feeds on shrubs, grasses, and fruit. It eats about 34 kg of foliage daily. When stressed, it can chew the bark of branches. Although herbivorous, giraffes have been observed visiting the carcasses of dead animals to lick the dried meat off the bones.

The height gives them an important advantage in their diet, since they do not compete with other types of fauna to access the vegetation. Only the largest elephants could reach the topmost leaves of the acacia trees, but this does not represent a conflict that affects the feeding habits of both parties.

During the rainy season, food is plentiful and giraffes are more dispersed, while during the dry season, they concentrate around the remaining evergreen trees and shrubs. Mothers tend to feed in open areas, probably to facilitate predator detection, although this can reduce feeding efficiency. As a ruminant, the giraffe first chews its food, swallows it for processing, and then visibly passes the half-digested cud up its neck and into the mouth to chew it again. It is common for saliva when feeding. Giraffes require less food than many other herbivores, because the foliage they eat contains a higher concentration of nutrients and because they have a more efficient digestive system. they appear in the form of small balls. When he has access to water, he drinks at intervals of no more than three days.

Giraffes have a marked effect on the trees they use for food, retarding the growth of saplings for several years and creating a characteristic "waist" on taller trees. Feeding is mainly concentrated during the first and last hours of the day. Between these hours he is usually standing ruminating. Rumination is also the dominant activity at night, when it is practiced mainly lying down.

Social life and reproduction

Giraffes are generally found in groups, although they are open groups whose composition tends to change constantly. They have few strong social bonds, and groups often change members every few hours. For research purposes, "group" was defined as "a collection of individuals less than a kilometer apart and moving in the same general direction". The number of giraffes in a group can vary to include 32 individuals. The most stable groups are those made up of mothers and their young, which can stay together for weeks or even months. Social cohesion in these groups is maintained through the bonds formed between the hatchlings. Mixed groups composed of adult females and young males also occur. Subadult males are particularly social and engage in mock fighting. However, as males grow older they become more solitary. Giraffes are not territorial, although they do have a home range. Males occasionally wander far from the areas they normally frequent.

Reproduction is largely polygamous: older males mate with fertile females. Males assess fertility by testing the female's urine for estrus in a multi-step process known as the Flehmen response. Males prefer young adult females over younger or older females. When detecting a female in heat, the male will try to court her. During courtship, the dominant male will keep subordinate males at a distance. During copulation, the male stands on his hind legs with his head up and his forelegs resting on the flanks of the female.

Although generally silent and non-vocal, giraffes can use various sounds to communicate with each other. During courtship, males emit loud coughs. Females call their young by mooing. The hatchlings make snorts, bleats, moos, and meow-like sounds. Giraffes also produce sounds such as grunts, hisses, moans, and hisses; over long distances they communicate with each other using infrasound.

Childbirth and parental care

After a gestation period of 400-460 days, the female normally gives birth to a single young, although twins may rarely be born. The female gives birth standing up. The calf emerges head and forelegs first, after rupturing the fetal membranes, and falls to the ground, severing the umbilical cord. The mother then cleans the newborn and helps it to its feet.

A newborn giraffe is about 1.8m tall. Within hours of birth, the calf can run and is nearly indistinguishable from a week-old calf. However, for the first 1–3 weeks, it spends most of its time in hiding; its fur pattern provides adequate camouflage. Within a few days after birth, the ossicona, which remained flat while in the uterus, become erect.

Females with young often gather in herds of young, browsing and moving together. Occasionally, some females in a breeding herd may leave their young with another female while they feed and drink elsewhere. This is known as "giraffe nursery". Adult males do not play a noticeable role in raising the young, although they appear to have friendly interactions. Calves are at risk of predation, and a female will remain on top of her calf. and will kick an approaching predator. Females guarding calves in a giraffe nursery will only alert their own calves if they detect a disturbance or danger, although other calves will notice and follow as well. the female and her calf varies, although it may last until the next calving. Similarly, calves may suckle for as little as a month or as long as a year. Females reach sexual maturity when they are four years old, while Males mature at four or five years. However, males have to wait until they are at least seven years old to gain a chance to mate.

Neck Fencing

Males use their necks or necks as weapons in combat with rivals, a behavior known as necking. Neck fighting is used to establish dominance between males; males that win these duels have greater reproductive success. This behavior occurs at low or high intensity. In low-intensity duels, combatants rub and lean against each other with their necks. The male that manages to remain more erect wins the duel. In high-intensity duels, males will extend their front legs and pivot their necks to strike the other with great force with their ossicones. Contestants will try to dodge each other's blows and then prepare to counter. The force of the blows depends on the weight of the skull and the arc of the swing. A duel can last more than half an hour, depending on the balance of forces between the combatants. Although most duels do not result in serious injuries, there are records of broken jaws, broken necks and even deaths.

After a duel, it is common for the two males to caress and court each other, leading to mounting and climax. Such interaction between males was found to occur more frequently than heterosexual mating. In one study, up to 94% of mounting incidents were recorded to have occurred between males. The proportion of same-sex activities varied from 30 to 75%. Only 1% of same-sex mounting incidents occurred between females.

Mortality and health

Giraffes have a life expectancy of up to 25 years in the wild, exceptionally long-lived compared to other ruminants, Due to their size, good eyesight, and powerful kicks, adult giraffes are generally not subjected to predation. However, they can be preyed upon by lions, and are even common prey for them in Kruger National Park. Nile crocodiles can also pose a threat to giraffes when they stoop down to drink. Calves are much more vulnerable than adults, and are also preyed upon by leopards, spotted hyenas, and wild dogs. Between a quarter and a half of calves reach adulthood.

To prevent attacks by ground predators while drinking, giraffes travel in small groups and take turns crouching. One or two of them are in charge of looking in different directions while the others remain bent over drinking liquid. When you're done, it's your turn to watch. In the face of crocodile attacks, there is not much they can do, because when receiving a bite to the neck, the body loses its balance forward.

Giraffes are affected by different parasites. They are often hosts to ticks, especially in the area around the genitalia where the skin is thinner than in other areas. The species of ticks that commonly feed on giraffes belong to the genera Hyalomma, Amblyomma and Rhipicephalus. Giraffes rely on birds such as the yellow-billed oxpecker and red-billed oxpecker to rid them of ticks and alert them to danger. Giraffes harbor numerous species of internal parasites and are susceptible to various diseases. They fell victim to rinderpest, a viral disease (now eradicated).

Relationship with man

History and cultural significance

Humans have interacted with giraffes for millennia. The San people of southern Africa have medicinal dances with the names of some animals; the giraffe dance is performed to treat head ailments. The origin of the giraffe's height has been the subject of several African tales, including one that the giraffe grew by eating too many magical herbs. Giraffes they were depicted in traditional art throughout the African continent, including that of the Kifians, Egyptians, Meroitics, and Nubians. The Kifians created a rock carving of two life-size giraffes which has been characterized as the "largest petroglyph in art cave world". The Egyptians gave the giraffe their own hieroglyph, called "sr" in Ancient Egyptian and "mmy" in later periods. They also kept giraffes as pets and shipped them to various sites in the Mediterranean region.

The giraffe was also known in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, where it was believed to be a natural hybrid of a camel and a leopard and was called camelopardalis. The giraffe was one of the many animals captured and exhibited by the Romans. The first giraffe in Rome was brought by Julius Caesar in 46 BC. and exhibited to the public. With the fall of the Roman Empire, the number of giraffes housed in Europe also declined. During the Middle Ages, giraffes were only known to Europeans through contact with the Arabs, who revered the giraffe for its peculiar appearance.

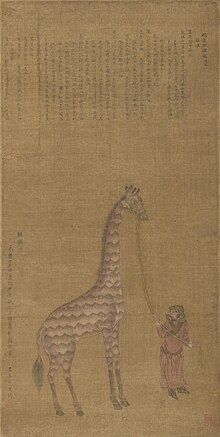

In 1414, a giraffe was sent from Malindi to Bengal. It was then taken to China by explorer Zheng He and placed in a Ming Dynasty zoo. The animal was a source of fascination for the Chinese people, who associated it with the mythical Qilin. The "Medici giraffe" was a giraffe presented to Lorenzo de Medici in 1486. It caused a stir upon its arrival in Florence. Another giraffe famous was the one that was brought from Egypt to Paris at the beginning of the XIX century as a gift from Mehmet Ali of Egypt to Charles X of France. The giraffe became a sensation and the subject of numerous memorabilia or "giraffanalia".

Giraffes continue to have a presence in modern culture. Salvador Dalí depicted them with conflagrated manes in some of his surrealist paintings. Dalí considered the giraffe a symbol of masculinity, and a flaming giraffe represented a "masculine apocalyptic, cosmic monster". Several children's books feature the giraffe, such as The Giraffe Who Was Afraid of Heights by David A. Ufer, Giraffes Can't Dance by Giles Andreae, and The Giraffe, the Pelican and the Monkey by Roald Dahl. Giraffes appeared in animated films, including as minor characters in Disney's The Lion King and Dumbo, and in a more prominent role in The Wild films. i> and Madagascar. Sofia the Giraffe has been a popular teether for children since 1961. Another famous fictional giraffe is the Toys mascot "R" Us known as Geoffrey the giraffe. The giraffe is also the national animal of Tanzania.

The giraffe was also used for some scientific experiments and discoveries. Scientists analyzed the properties of giraffe skin to develop suits for astronauts and fighter pilots because people in these professions risk losing consciousness if blood flows to their feet. Computer scientists modeled the coat patterns of various giraffe subspecies using reaction-diffusion mechanisms.

The constellation Camelopardalis, introduced in the 17th century century, represents a giraffe. The Tswana people of Botswana considered the constellation Crux as two giraffes: Acrux and Mimosa representing a male, and Gacrux and Delta Crucis representing a female.

Exploitation and conservation status

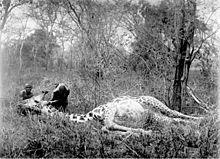

Giraffes were probably common targets for hunters throughout Africa. Different body parts were used for various purposes. The meat was used for food. The hairs of the tail served as fly swatters, bracelets, necklaces, and thread. The skin was used to make shields, sandals, and drums, and the sinews served as strings for musical instruments. Buganda healers used smoke from the burning giraffe skin to treat nosebleeds. The Humr people of Sudan consume the drink Umm Nyolokh, which is made from the liver and bone marrow of giraffes. Umm Nyolokh often contains DMT and other psychoactive substances derived from plants giraffes eat, such as Acacia, and is said to cause giraffe hallucinations, which the Humr say are giraffe ghosts. style="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">XIX, European explorers began hunting giraffes for fun. The giraffe also suffered from habitat destruction. Although the giraffe can coexist with cattle, since they do not compete directly for food, in the Sahel the demand for firewood and grazing areas for cattle led to deforestation.

The giraffe was classified as a species of Least Concern by the IUCN, as it remains numerous. However, it has been extirpated from much of its historical range including Eritrea, Guinea, Mauritania, and Senegal. It may also have disappeared from Angola, Mali, and Nigeria, although it was introduced to Rwanda and Swaziland. Two subspecies, the West African giraffe and Rothschild's giraffe, were listed as endangered because only a few hundred remain. in the wild. In 1997, Jonathan Kingdon suggested that the Nubian giraffe was the most threatened of all. It may have numbered fewer than 250 in 2010, although this estimate is uncertain. Private game reserves contributed to conservation of giraffe populations in southern Africa. Giraffe Manor is a well-known Nairobi hotel, which also serves as a sanctuary for Rothschild's giraffes. The giraffe is currently a protected species throughout most of its range. In 1999 the population in the wild was estimated to be over 140,000 giraffes, but estimates for 2010 indicated that this total had declined to less than 80,000.

Contenido relacionado

Notoryctidae

Dendrology

Squarrosa wood