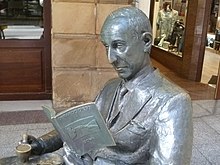

Gerardo Diego

Gerardo Diego Cendoya (Santander, October 3, 1896 - Madrid, July 8, 1987) was a Spanish poet, teacher and writer belonging to the so-called generation of '27.

Biography

Gerardo Diego himself dictated an autobiography, which is preserved in the foundation that bears his name. He was the seventh child of Manuel Diego Barquín (who had three others from a previous marriage from which he became a widower) and Ángela Cendoya Uría, owners of a textile store in Santander and quite pious (Gerardo had two Jesuit brothers); in his childhood he saw two of his brothers die and watched the walks of José María de Pereda along the pier; he also frequented the house of the Menéndez Pelayo family, acquaintances of his father, of whom he especially treated the librarian Enrique. From an early age he stood out for his versatility in the artistic field: he learned solfeggio, piano and a little later painting, and, stimulated by one of his teachers, the great critic Narciso Alonso Cortés, he began to read a lot and feel a great interest in the rhetoric of the textbook by Nicolás Latorre.

He was a student at the University of Deusto, where he studied Philosophy and Letters and met who would later be an essential friend in his literary life, Juan Larrea. In 1916, however, he traveled to Madrid to take the exam for the last year and do his doctorate, and frequents the Ateneo, the itinerant ultraist gathering of Rafael Cansinos Assens and that of Ramón Gómez de la Serna in the Pombo café; Fascinated, he attends the premiere in Madrid of Stravinsky's The Firebird , with choreography by Diaghilev, and he never misses a concert.

He obtained a literary prize in 1917 from Editorial Calleja. His first literary collaboration dates from 1918, the year in which he met the great Chilean avant-garde poet Vicente Huidobro in Madrid; in 1919 he published his first poem and on November 15 he gave the conference "The new poetry" at the Ateneo de Santander and unleashed a controversy about ultraism in the local press; he repeats it on December 27 at the Ateneo de Bilbao, where he is presented by Juan Larrea. With the help of León Felipe and Juan Ramón Jiménez, in 1920 he managed to print his first book of verses, El ballads of the bride, and on April 9 he obtained a chair of Language and Literature in Soria, where he late still the presence of Antonio Machado. He will later hold the same chair in Gijón, Santander and Madrid. Also in that year, guided by José María de Cossío, whom he had just met, he began his studies on poetry of the Golden Age, discovering the manuscript of the anonymous Fable of Alpheus and Arethusa in the Library Menendez Pelayo; over time he will become a great connoisseur of the poetry of Lope de Vega and Antonio Machado, who are the authors he quotes the most, feeling especially fascinated by mythological and bullfighting matters, which interest Cossío so much, but from a perspective on all iconological and iconographic. He begins his correspondence with Huidobro. The first magazines in which he published were Grail Magazine, Castilian Magazine and the avant-garde Grecia, Reflector, Cervantes and Ultra.

In Santander he directed two of the most important magazines of 27, Lola and Carmen; This helped him establish relationships with the top brass of the generation of '27 and make it known in his later famous anthology, Spanish Poetry: 1915-1931 (1932). But, for now, in 1922 he is invited by the Chilean avant-garde poet Vicente Huidobro to visit France and Normandy. There he met the cubist painters Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, Jacques Lipchitz and María Blanchard and many of the other great avant-garde artists of the moment; Back in Spain, he moved to the Jovellanos de Gijón Institute, where he would remain until 1931; he published his first avant-garde collection of poems: Image: poems (1918-1919) (Madrid, 1922), with a cover by Pancho Cossío; his link to creationism is clear: «Creating what we will never see, this is poetry». In 1923 he published Soria . He visits Unamuno in Salamanca and later in his Parisian exile. In 1924 he discovered a baroque eclogue dedicated to Isabel de Urbina in the Cossío library and edited the text, which is by the baroque poet friend of Lope, Pedro Medina Medinilla; publishes another avant-garde collection of poems, Manual de Espumas (Madrid: La Lectura, 1924), which will receive the National Literature Award the following year ex aequo with Rafael Alberti and his Sailor on land. The newspaper ABC explains it this way in its edition of June 10, 1925:

National Literature Competition. The Qualifying Jury, constituted by the Messrs. Menéndez Pidal, count of the Mortera, Machado (Antonio), Arniches and Moreno Villa, has ruled in the contest corresponding to 1924. The Poetry Prize has been awarded to D. Rafael Alberti. The theatre was deserted, but its amount has been transferred to another section and awarded to D. Gerardo Diego, for a book of verses.

He took advantage of the amount of the prize to travel through Andalusia in 1925; the composer Manuel de Falla, with whom he corresponds, serves as his guide through Granada; He publishes Versos humanos (Madrid: Renacimiento, 1925), a collection of songs, sonnets and odes in its neoclassical aspect. In April 1926, he forged in a coffee gathering with Pedro Salinas, Melchor Fernández Almagro and Rafael Alberti to celebrate the Centenary of Luis de Góngora and a plan of editions and conferences demanding the second "dark" era of the Baroque poet, which they consider the most modern and avant-garde; Alberti was appointed secretary of the commission and Dámaso Alonso, José Bergamín, Gustavo Durán, Federico García Lorca, José María Hinojosa, Antonio Marichalar and José Moreno Villa also signed up. At that time he was already known as one of the main followers of the Spanish poetic avant-garde together with Guillermo de Torre and Juan Larrea, and specifically of ultraism and creationism, and he participates in the Parisian magazine directed by Juan Larrea and the great Peruvian expressionist poet César Vallejo, Favorable Paris Poem (1926). On the occasion of a tribute from the Ateneo de Granada to the Gongorian poet Pedro Soto de Rojas, Diego sends a fragment of his Fábula de Equis y Zeda, which Federico García Lorca reads. He collaborates in Revista de Occidente and in Litoral of Malaga. Finally, in 1927, acts (including some quite irreverent ones) were carried out to honor the memory of the last Góngora and offend his critical enemies, especially Luis Astrana Marín. In December of that year his magazine Carmen came out, and to match it he also called his supplement, Lola , with another authentic woman's name. In 1928 he traveled through Argentina and Uruguay, giving recitals-concerts and conferences, and in 1931 he was transferred to the Santander Institute.

He wrote the two versions (1932 and 1934) of the famous anthology Spanish Poetry that made the authors of the generation of '27 known, but which is chronological and includes the three generations of the silver age, beginning with Unamuno and Machado, as well as a poetic autograph from each author; but receives criticism from Miguel Pérez Ferrero, César González Ruano and Ernesto Giménez Caballero. However, it makes the new poets of '27 known. Villaespesa, Eduardo Marquina, Enrique de Mesa, Tomás Morales, José del Río Sainz, Alonso Quesada, Mauricio Bacarisse, Antonio Espina, Juan José Domenchina, León Felipe, Ramón de Basterra, Ernestina de Champourcín and Josefina de la Torre.

In 1932, he published two books in Mexico: Fábula de Equis y Zeda, a parody of mythological fables in Gongorian style, and Poemas adrede. He is a music critic for El Imparcial , and the following year for La Libertad . As a teacher, he gave courses and lectures all over the world. He was also a literary, musical and bullfighting critic and a columnist in several newspapers. In 1934 he married a French woman, Germaine Marin, from whom he would have six children, and the following year he traveled to the Philippines with the mathematician Julio Palacios to give lectures and defend Hispanic literature; In that same year he moved as a professor to the Santander Institute. His poetic task continues to be completed with his studies on different themes, aspects and authors of Spanish literature, with his work as a lecturer and his outstanding music criticism, carried out from different newspapers.

The Civil War broke out when he was on vacation in Sentaraille (France) with the family of his wife, Germaine Berthe Louise Marin, twelve years his junior and whom he had met in 1929, and only returned in August 1937, when Santander falls into the hands of the national side. Unlike many of his colleagues, Gerardo Diego sided with the rebels and remained in Spain at the end of the war. He wrote articles in the Falangist newspaper La Nueva España of Oviedo, participated in the Corona de sonetos a José Antonio Primo de Rivera and in the collective book Laureados dedicated to the heroes of Francoism, as well as writing a Heroic Elegy of the Alcázar; He also participates in the regime's magazines: Vértice, Tajo, Santo y Seña, Ecclesia, Radio Nacional, El Español, the newspapers Arriba and Informaciones and in La Nación of Buenos Aires. All this, and not having done anything to free Miguel Hernández, earned him the sentence of Pablo Neruda in some verses of his Canto general, which were answered by Leopoldo Panero in his "Canto personal& #34;. Despite everything, he wrote in his Autobiography:

The war... did not sneeze the slightest to preserve our friendship, and even the ever-increasing divergence in the respective poetics, because some began to make a more or less surreal poetry, such as Aleixandre, who was the first to begin, or Cernuda, and others also gave more heat and more passion to his poetry. Alberti changed too suddenly and began to make the books, Sermons and dwellings, more full of stronger sentences against the bourgeoisie and of a political type. However, we were still trying and encouraging ourselves and wanting as always and we were always seeing that there was occasion at dinner or in the tertulia. For that time it is also the arrival of Neruda to Madrid, in 1932, if I do not remember badly. Neruda also had tertulia in his house, although he sometimes went to other places, and came to coincide with the arrival of Miguel Hernández, who came here to perfect his spontaneous literary formation, but already so rich and full of natural gifts. He was lucky to meet Cossío who helped him, because he placed him in Espasa-Calpe to help him make the book. The bullswith graphics and organizational work. I was one of the first to meet him because he had sent me his first book, Perito on moons. We all loved Miguel a lot. The Republic came, things were found more, within the same Republic, on different sides, coinciding all this with my Madrid march and my return to Santander. It was then that a group of friends and admirers of Juan Ramón founded in Seville a magazine to exalt the idealist type and beauty of poetry, taking Juan Ramón as a teacher, and instead, Neruda founded Green horse for poetry that edited Manuel Altolaguirre, in which he argued that poetry should have dirty hands, be stained with the lexicon of all days and be reflecting all the realities of the moment. For this reason a tremendous controversy was set...

Once the civil war was over and not only the one established between pure and impure poetry, he moved to the Beatriz Galindo Institute in Madrid, where he would remain until his retirement in 1966. During the postwar period, Diego repeated his political poems in defense of the rebels and the Falangist volunteers of the Blue Division, and writes in Leonardo, Garcilaso, Revista de Indias, Proel, Signo, La Estafeta Literaria, the Magazine of Political Studies and Music. He also claims the work of Miguel Hernández in various articles.

In 1940 he printed Ángeles de Compostela, a very ambitious book in which the central figures are the four angels of the Portico of Glory in the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, who represent the four End Times of man: death, judgment, hell and glory. In 1941 he published Alondra de verdad , a collection of forty-two extraordinarily well-crafted sonnets in which he sought pure and authentic lyrics, within the garcilasismo or rooted poetry. Since 1947 he was a member of the Royal Spanish Academy. He returns to the forefront with Limbo (1951). He writes numerous prose texts for the radio. In 1956 he obtained the José Antonio Primo de Rivera National Prize for his work Landscape with Figures . In 1962 he obtained the Calderón de la Barca for his scenic altarpiece The cherry tree and the palm tree , his foray into the theater. He retired in 1966. In 1969, a Cantata on Human Rights premiered at the Teatro Real in Madrid with his lyrics and music by Óscar Esplá.

In 1979, he was awarded the Cervantes Prize, which curiously turned out to be the only time that two people were awarded in the same year (the other winner was the Argentine Jorge Luis Borges). He died in Madrid of bronchitis on July 8, 1987, at the age of ninety.

Poetics

He represented the ideal of 27 by masterfully alternating traditional and avant-garde poetry, the latter within ultraism and especially creationism, of which he became one of the greatest exponents during the decade of the twenties. His poetic work thus follows these two lines. But he also exposed his conviction that there were two types of poetry: the relative and the absolute, as can be seen in the prologue to an anthology of his verses from 1941:

- My sincerity has always been absolute... I have put in every one of my books and my verses the maximum authenticity of emotion. That he will then lose himself in the rocks of the mechanism, it will already be my verbal insufficiency and my technical clumsiness... I am not responsible for being attracted simultaneously to the countryside and the city, tradition and the future; that I love the new art and extacite the old; that the rhetoric made me go crazy, and I become mader the whim of getting it back—new—for my personal and intransferable use. There are hours to explore through those worlds and hours to get locked up alone with their memories. And all that... we have to solve it with the beekeeper. All these concerns are reduced in me to two single intentions. Those of a relative poetry, that is, directly supported in reality, and that of an absolute poetry or tendency to the absolute; that is, supported in itself, autonomous in the face of the real universe of which only in the second degree proceeds. The latter, of course, is more difficult and occupies within my work a less extensive surface. But if more difficult is not in me less constant - see dates- no less "human". The title of one of my books has been able to mislead my intentions

His traditional poetry includes poems of traditional and classicist metrics in which he resorts to romance, the décima and the sonnet, above all, but also more occasionally to the lyre or the octave real. It is common, however, that the poet founds the avant-garde with the Gongorian baroque until it is not possible to distinguish where one or the other begins, as in the Fable of Equis and Zeda. The themes are very varied: the landscape (The Pilgrim's Return), religion (the books devoted to Ángeles de Compostela, Via Crucis and Versos divinos), the music (Prelude, aria and coda to Gabriel Fauré), the bulls (Eclogue by Antonio Bienvenida, La suerte or death), love (Love alone, Songs to Violante, Sonnets to Violante), humor (Carmen Jubilee, 1975) etc. The social, except for his Odas morales (1966), almost does not appear, and even less so the political, except for the already mentioned poems of circumstances. Metaphysical and transcendent concerns are also strange in his poetry (the nearby world, his experiences and memories, people he knows or admires, usually focus his attention), although he deals with the subject of death in his book Civil Cemetery (1972). Complex books composed over the years are Incomplete Biography, which some call surreal; Landscape with figures, Farewell, The branch, The moon in the desert and other poems. His is the one considered by many to be the best sonnet in Spanish literature, El cypress of Silos, as well as other important poems such as Nocturno, Las tres hermanas i> or The farewell. He also cultivated literary criticism, collected in his Complete Works , but also in free-standing volumes such as Crítica y poesía (Madrid: Júcar, 1984).

His inclination for new avant-garde art led him to initiate himself first into creationism, exercising dazzling but dehumanized imagery, the lack of punctuation marks, the use of white space, dynamic typography in the verses and inconsequential themes in a playful and autonomous poetry that, as he says in one of his poems, sleeps "with the dream of Holofernes".

It is noteworthy the influence of Gerardo Diego on other relevant figures both nationally and regionally. Among his followers, he stands out the Cantabrian poet Matilde Camus, of whom he was a professor at the Santa Clara Institute in Santander. In 1969, Gerardo Diego sent a poem entitled Canción de corro for the prologue of the first book by Matilde Camus entitled Voces and which was released at the Ateneo de Madrid. Likewise, the correspondence he maintained with Matilde Camus will soon be published.

Works

- Complete Worksed. by Francisco Javier Díez de Reven and José Luis Bernal, Madrid: Alfaguara, 1997-2001, 9 vols., 3 lyric and 6 prose.

Lyrical

- Complete poetry, I and II, prepared by the author before his death, 1989; reprinted in Valencia: Pre-texts, 2017.

- The romance of the brideSantander, Imp. J. Pérez, 1920.

- Image. Poems (1918–1921), M., Graphic of Both Worlds, 1922.

- Soria. Gallery of prints and efusions, Valladolid, Friends' Books, 1923.

- Foam Manual, M., Cuadernos Literarios (La Lectura), 1924.

- Human Verses, M., Renaissance, 1925 (National Prize for Literature 1924-1925).

- Viacrucis, Santander, Aldus Workshops, 1931.

- Fábula de Equis y ZedaMexico, Alcancía, 1932.

- Poems adredeMexico, Alcancía, 1932.

- Angels of Compostela, M., Patria, 1940 (new full version: M., Giner, 1961).

- Real AlondraM., Escorial, 1941.

- First anthology of his versesM., Espasa-Calpe, 1941.

- Romances (1918-1941)M., Patria, 1941.

- Poems adredeM. Col. Adonais, 1943 (Full Edition).

- The surpriseM., CSIC, 1944.

- Even foreverM., Messages, 1948.

- The moon in the desertSantander, Vda F. Fons, 1949.

- Limbo, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, El Arca, 1951.

- Visitation of Gabriel MiróAlicante, 1951.

- Two poems (Divine verses)Melilla, 1952.

- Incomplete biography, M., Hispanic Culture, 1953 (Joseph Knight's Illustrations. Second edition with new poems: M., Hispanic Culture, 1967).

- Second dream (Homenaje a Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz)Santander, Col. Tito Hombre, 1953 (Xilographs of Joaquín de la Puente).

- VariationM., Neblí, 1954.

- AmazonM., Ágora, 1956.

- Celebrate Antonio WelcomeSantander, Ateneo, 1956.

- Landscape with figures, Palma de Mallorca, Papers of Sons Armadans, 1956 (National Literature Award).

- Love alone, M., Espasa-Calpe, 1958 (Barcelona City Award 1952).

- Songs to ViolanteM., Punta Europa, 1959.

- Gloss to VillamedianaM., Word and Time, 1961.

- The branchSantander, The island of mice, 1961.

- My Santander, my cradle, my wordSantander, Diputación, 1961.

- Sonnets to ViolanteSeville, La Sample, 1962.

- Luck or death. Toreo PoemM., Taurus, 1963.

- Chopin NewsM., Bullón, 1963.

- El jándalo (Seville and Cadiz)M., Taurus, 1964.

- Lovely Poetry 1918–1961B., Plaza and Janés, 1965.

- The Cordobes diluted and returned from the pilgrim, M., Revista de Occidente, 1966.

- Moral wavesMalaga, El Guadalhorce Antique bookstore, 1966.

- Variation 2, Santander, Classics of All Years, 1966.

- Second anthology of his verses (1941–1967)M., Espasa-Calpe, 1967.

- The foundation of want, Santander, The island of mice, 1970.

- Divine Verses, M., Alforjas for Spanish poetry (Fundación Conrado Blanco), 1971.

- Civil cemetery, B., Plaza and Janés, 1972.

- Carmen retirerSalamanca, Alamo, 1975.

- Wrong kit, B., Plaza and Janés, 1985.

- Decir de La Rioja, Berceo Gonzalo Library.

Theater

- The cherry and the palm tree. Madrid: Alfil, 1964.

Translations

- Take it. Poetic versions. Madrid: Ágora, 1959.

Editions

- VV. AA. Spanish poetry: 1915-1931 (1932).

- Lope de Vega, Rimas. Madrid: Taurus, 1963

| Predecessor: Damaso Alonso |  Miguel de Cervantes Award «ex aequo» Jorge Luis Borges 1979 | Successor: Juan Carlos Onetti |

Contenido relacionado

Moby Dick

Mathilda May

Gustave Flaubert